Abstract

The purpose of this chapter is to review disaster relief community-based mental health resources. The goal is to learn how these resources can be adapted to encompass a community-driven perspective. It examines evidence-based best practices in disaster relief on both a national and community level. These practices will be specifically related to recovery and relief efforts in New Jersey following Hurricane Sandy, but will be discussed in a broader context of implications for the Middle East. A foundation of community-based participatory research and critical consciousness will be used as a framework to develop potential interventions that will empower the community to acquire tools that will aid in their recovery.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

A key part of recovery , relief, and rebuilding following a disaster is access to relevant mental health resources. While there is a body of work surrounding evidence-based best practices, there is often a gap between what is theoretically correct and what is utilized in practice. In addition, many resources are focused on mainstream recovery and often neglect outreach to vulnerable populations. Many programs, both economically and socially/emotionally, are also initiated outside of affected communities without direct input from those impacted, this can cause the survivors to become disempowered in the process and become potential bystanders of their own recovery. The purpose of this chapter is trifold to (1) review current disaster relief mental health practices with reference to the Middle East; (2) explore the theories of critical consciousness, international disaster relief, and community-based participatory research; and, (3) apply these three strategies to potential future mental health actions in the recovery, relief, and rebuilding stages following a disaster.

2 Disaster Relief Mental Health

Disaster relief mental health practice differs from traditional mental health practice in that emotions are normalized following a crisis in contrast diagnosing and treating typical pathology (McIntyre, 2009). Best practices state that following an immediate crisis, open discussion among peers is encouraged. The sharing of feelings and emotions, incidents that occurred and commiseration of loss, aids in the normalizing of reaction to the crisis (Farberow & Frederick, 1978). Also, this is seen in working with children by encouraging expression of feelings through art or writing, trying to maintain routine, excusing them from some ordinary tasks, addressing both the child’s and one’s own feelings about the disaster, and encouraging activity (SAMHSA, 2007). By utilizing schools, childcare centers, and other structures, services can be rapidly assessed and delivered to the widest variety of people, including working with vulnerable populations such as the elderly, people with physical and/or psychiatric disabilities, children, and people who are homeless or who are refugees, utilizing the already accessed systems is also crucial. Instead of waiting for people to come to providers, providers need to utilize preexisting system structures.

Mental health resources are considered most beneficial when they are flexible, empowering, compassionate, and respectful (National Biodefense Science Board (NBSB), 2008). Services should address both the individual and community needs in a timely manner. Essential to the implementation of evidence-based practice is the training of responders in post-traumatic stress management. Focus should be on increasing resiliency and decreasing vulnerability to promote proficiency in self-care. While highly trained professionals are crucial to a disaster response, it is equally necessary to utilize grassroots organizations to mobilize in their communities following a disaster as there will not be time or resources to solely rely on mobilizing highly trained professionals (NBSB, 2008). Creating a dialogue with the community instead of merely issuing commands is also highly recommended. Through conversation, practitioners can consistently embrace and work with cultural differences in each community. Working to educate the community on why certain actions are being taken is increasingly important to promote empowerment and remain focused (NBSB, 2008). General consensus among experts in the field is that interventions may not need to be clinical or have a pathological focus, but do need to involve community supports. Crucial elements in the relief and rebuilding stages are creating a sense of safety, calming, sense of self and community efficacy, social support and connectedness, and hope (Hobfoll et al., 2007; McIntyre & Nelson Goff, 2011).

3 Coping Practices in the Middle East

Disaster relief has a different character in the Middle East as it usually focuses more on terrorism, particularly in the last 15 years when the Al-Aqsa Intifada erupted in September 2000 (Perliger & Pedahzur, 2015). The media contributed to the extensive and graphic images that were seen in real time and often repeatedly, contributing to the shared sense of a significant national crisis (Bleich, Gelkopf, Melamed, & Solomon, 2006). Furthermore, it has been noted that very little is known about how to cope with the chronic threat of terrorism (Dickstein et al., 2012). The little research that has been done, particularly on individuals in the Middle East exposed to chronic terrorism, shows that some of these individuals develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while others remain resistant with a low level of stress and/or impairment; also, there is another group that can remain resilient and carry on with their lives seemingly “bouncing back” with little impact (Dickstein et al., 2012). Knowing that individuals can be resistant or resilient, Dickstein et al. (2012) felt it was important to understand the factors that bolster this type of response to promote the highest levels of coping possible.

To address the issue of coping and the impact on mental health, Dickstein et al. (2012) gathered data in 2009 on the mental health impacts following conflict, 7 months after the Gaza War of 2008 . Structured telephone interviews consisting of 100 questions were conducted of 450 Hebrew- and Russian-speaking residents of Sderot and Otef Aza (bordering the Gaza Strip), who were 18 years and older. Using exploratory factor and moderation analysis, these researchers found that the three coping factors where being used maladaptively: denial, disengagement, and social support seeking were detrimental to psychological functioning. To explain the counterintuitive result of social support being detrimental, the researchers noted that the interviews took place at a point where stressors were still present and, within the context of ongoing trauma, the respondents did not feel that they could adequately help others while trying to help themselves (Dickstein et al., 2012). The one factor that they found that was protective against psychological distress was acceptance and positive reframing (77.1 % of the sample reported using this strategy). This reframing was also associated with lower levels of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress. All three of the detrimental factors noted above were associated with increasing these mental health outcomes. The use of acceptance and positive coping was seen by the researchers as a reasonable coping strategy in the face of the uncontrollable nature of chronic stress and terrorism, where problem-focused strategies may be less effective.

It is well documented that risk and resiliency factors impact mental health outcomes in studies conducted in both US and Israeli populations, but the mechanism of how they impact is not yet clear (Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, & Johnson, 2006). One theory that has successfully predicted outcomes is the conservation of resources theory (COR) , especially in response to war, terrorism, and disaster (Hobfoll, 2012). The COR theory suggests that consequence of stress can emerge from either an actual loss or the threat of loss of physical/material resources or psychosocial resources such as social support. Ironically, in the face of terrorism, the theory suggests that resiliency and continued maintenance of stress resistance resources are needed to confront terrorism, yet these are the exact facets that terrorism threatens. Thus, Hobfoll et al. (2006) argue that because terrorism has a collective nature in how it impacts communities, this leads to increased social support and coping. In their study, Hobfoll et al. (2006) found that of the 905 adult Jewish and Arab citizens of Israel exposed to terrorism, those with greater social support were also less likely to develop depressive symptoms or PTSD. These researchers felt that their findings pointed to the need for secondary prevention of mental health disorders, suggesting that media and public officials should be communicating messages regarding forms of social support and effective coping that can bolster resiliency rather than just broadcasting messages of fear.

4 Crisis Intervention (Relief and Recovery)

Mental health services following an immediate crisis currently come from a variety of sources. Among these are international, national, and regional mental health resources as well as local community organizations (World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International, 2011). There are currently no set of guidelines on how they are coordinated (NBSB, 2008). However, for the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasis is placed on psychological first aid (PFA) (World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International, 2011). For example, within the USA, following the 9/11 attacks, the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) gathered top professionals in the fields of mental health, trauma, and resiliency to create guidelines on how to most efficiently respond to communities following a disaster (McIntyre & Nelson Goff, 2011). The following operationalized interventions were noted as being essential in immediate response: preparation, planning, education, training, and service provision. This follows an established hierarchy of needs including safety, shelter, food, and medical care; the acceptance of the interventions should be voluntary. Consensus of evidenced-based practices among the NIMH participants concluded that early, brief, and focused psychosocial interventions will reduce distress and that cognitive behavioral approaches will reduce incidence, duration, and severity of PTSD, and depression (NIMH, 2002).

It has been noted that the period of early intervention begins immediately following the disaster and lasts for approximately two weeks (NIMH, 2002). The goals of early intervention are survival, communication, adjustment, assessment, and planning. Expected behavior could move from fight or flight, to resilience and exhaustion, and to grief and narrative. The role of the responder would be to provide PFA (Macy & Solomon, 1995), starting at rescue and moving toward orienting and sensitivity. This would include assessing basic physical comfort and needs, determining immediate, available support systems, and compassionate listening (Macy & Solomon, 2010). The role of the mental health worker would start at the orienting phase and continue to subsequent stages. Activities would include conducting a needs and clinical assessment, performing outreach , fostering resiliency, and being available for consultation, training , and assistance to other agencies or caregivers. Opportunities would be created for social interaction, education about stress and coping skills, and providing group and family support while fostering the natural supports in the community (NIMH, 2002).

Employing PFA reduces painful emotions such as confusion, fear, anger, anxiety, grief, and loss of confidence in addition to reducing further harm. PFA is an eight-stage process. The first step is that of contact and engagement in a non-intrusive, culturally competent manner. Building respectful relationships is the fundamental basis. Second is the establishment of safety and comfort. This addresses the fight or flight reaction people may face following a disaster. Third is to calm and orient survivors. The goal is not to tell panicked people to calm down, but to be a stable presence in the community. Fourth is to gather information and tailor services to suit each individual and community. The fifth step is that of practical assistance. This includes helping people with decision-making skills and breaking large problems into small, manageable pieces. Sixth is to provide social support by providing consistent contacts with families and communities. There is evidence that mental health states improve after a crisis with consistent social support. Seventh is to provide information on coping and stress reduction to improve efficacy. The last is to provide linkage to collaborative services. By providing these links, survivors will know what options are available for future needs (Macy & Solomon, 2010; McIntyre, 2009).

Furthermore, PFA is a technique that is delivered on a foundation of trust and respect. Variations based on language, culture, religion/spirituality, and history must be taken into consideration. Workers should be present in the community from the beginning to build a foundation of trust. From the beginning, there should be a sense of pulling together and working as a community. If mental health workers are present at this time in the community, they are more likely to be seen as part of this community (McIntyre, 2009).

In addition to PFA, the second model currently being used for disaster relief mental health is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Crisis Counseling Program (CCP) (FEMA, 2012). CCP normalizes reactions to disaster and helps individuals and communities develop coping skills with the goal of returning to pre-disaster mental health status. CCP assesses strengths to bring hope to communities and aims to assist the return of pre-disaster community conditions. This happens by assessing the needs of a community and identifying if and where a breakdown occurs. The goal of CCP is to support infrastructure until it can be once again maintained by the community. The model utilizes community members of the affected community to provide services, following the concept that people will be more apt to talk to someone they know. CCP responders are not necessarily mental health professionals, but instead, will refer to mental health agencies if a need is identified. Lastly, responders disseminate educational materials about reactions, mitigation, where to find help, and what to expect (McIntyre, 2009).

In an effort to better understand how to reach the more vulnerable populations (e.g., elderly, children, homeless, persons with mental illness), in September 2013, two focus groups of stakeholders (program directors, employees, and volunteers) were conducted to assess the impact of Hurricane Sandy, a disastrous rain storm that hit New York and New Jersey in October 2012, on communities (Findley, Indart, & Kley, 2015). The focus of the groups was on the vulnerable populations in Ocean County, New Jersey, a county in New Jersey that was particularly hard hit by the storm. Observations from those groups included that during this initial phase following disaster, there was a lack of communication and a disruption of services for vulnerable populations. There is no statewide electronic medical list and people who evacuated to shelters may have been left without adequate medication. Some medical doctors and psychiatrists volunteered at shelters but were hesitant to fill prescriptions for psychotropic medication without adequate information. Shelters were also unprepared to take in people with various special needs including those on respirators, those with phobias, and those on methadone. In addition there was no information provided about those on Megan’s list (i.e. a list of individuals convicted of sexually assaulting a child); thus families with children were placed in a vulnerable safety situation. This reiterates the need for mental health program planners to be present at disaster planning and implementation meetings on local, county, state, and federal levels (Focus Group, September 2013). If these plans are in place ahead of time, it was felt that there would have been a more immediate assessment, access, and availability of mental health services.

5 Rebuilding (Long-Range Goals)

The rebuilding period begins several weeks following a disaster and lasts for 2–10 years depending on the severity of the disaster (Norris et al., 2002). Also, this is the time period when there may be significant private or governmental funding to organizations and agencies for mental health resources and programs. Following the initial recovery and repair, common mental health issues are adjustment and post-traumatic stress (McIntyre, 2009). Unlike the general consensus achieved by the experts about the relief phase, there is a lack of consensus on best practices about this intermediate stage (Hobfoll et al., 2007). Instead of specific recommended actions, there is a generally recommended framework with the purpose of maintaining flexibility due to the wide range of variables that could come from any disaster (Hobfoll et al., 2007). Included in these variables is how an event affects a community of people. This is illustrated as a line that denotes the difference between a stressful situation and one of trauma. The definition of this line must take into consideration the pre-disaster situation on a case-by-case basis.

Hobfoll et al. (2007) discuss four ways that differentiate between a stressful situation and trauma. First are the physical, social, or psychological effects on the community. This can be as major as seeing bodies floating in the river, people jumping from a burning building, or watching a town disappear. Second would be the devastation of resources especially on a community or group level that is already resource insecure. Also, this can be seen in a middle-income town where grant money is promised to rebuild but has yet to be realized. Third is the loss of attachment bonds, This loss can be seen through violence, forced relocation, or being relocated to another town away from friends and community structures and supports. Lastly, is the assumption of justice, apparent in some cases but, in the absence of such, traumatic in others. When a group of people live a certain way their entire life and then are forced into a situation where they are now dependent on a system that is nonresponsive to their needs, a sense of trauma is created (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

There are five aspects crucial to the framework for this stage of traumatic mental health resources. The first is maintaining a sense of safety. Studies show that those maintaining or reestablishing a sense of safety have lower rates of long-term stress, anxiety, separation anxiety, depression, phobias, and sleep disorders (Silver, Holman, McIntosh, Poulin, & Gil-Rivas, 2002). To return the sense of safety, there are several interventions that can be used including exposure therapy to restore the balance of normalcy for regular events. Equally to regain a sense of safety, it is crucial to avoid a pressure-cooker episode where people gather and consistently rehash the traumatic event and fill in unknown details with rumor (Hobfoll et al., 2007).

The second aspect of the framework is to create and maintain a sense of calm. This is essential to normalize and validate people’s reactions surrounding the disaster (McIntyre, 2009). When people understand their feelings as normal reactions to crisis, they will be able to move forward. While heightened emotional states are normal behaviors for a week or two following the event, long-lasted heightened emotional levels can be precursors to PTSD. These heightened emotional states can also lead one to overestimate the response to disaster in average events. Consensus for creating a sense of calm is a toolbox approach that includes deep breathing and muscle relaxing techniques, coping skills, role playing, problem solving, and positive thinking. Special attention should be made not to dismiss real worries that follow a traumatic event around economics, housing, employment, or structures (Hobfoll et al., 2007). In addition, a key aspect will be to educate people to use problem solving techniques. These will help break a large problem down into manageable parts (McIntyre, 2009).

Third is a sense of self and community efficacy or the belief that there will be a positive outcome to action with a positive reaction from peers. This is important in several domains including relationships, housing or relocation, employment or retraining, and community structures or rebuilding (Hobfoll et al., 2007). To maintain this efficacy, one must have resources and the purpose and skills to utilize them. For people to believe in themselves, they must possess the skills and tools to move forward. This combination will lead to resiliency and the ability to quickly adjust and handle crisis situations (McIntyre, 2009). Competent communities are those that promote this type of growth in both the individual and family unit (Hobfoll et al., 2007). Communities are collectives of families and when families are strong, communities are strong as well. Competent communities should provide both the resources and education to encourage this type of efficacy among individuals and families. By providing these resources, families will feel that through action, rebuilding is possible (McIntyre, 2009).

Two crucial elements for efficacy are necessary for success. The first is the concept of quick and consistent wins (Hobfoll et al., 2007). This embodies the same concept used earlier in problem solving. By breaking down the large process into smaller, tangible sections, the problems seem less looming and overwhelming. This can also be applied on a community level. By consistently and successfully tackling small projects, both the individual and communities believe they are moving forward and seeing reward for their actions. Projects will increase in difficulty and length over time as the community increases their efficacy. Secondarily, and significantly harder to amend, is the correlation between efficiency and access to resources. According to Hobfoll et al. (2007), research has shown that those who lose the most personal, social, and economic resources during a disaster are apt to be the most devastated. Equally, those who have access to resources to sustain have the best ability to recover. Simply stated, economically wealthier individuals and communities will have an easier time rebuilding than more impoverished neighborhoods and those with more secure support structures will socially and emotionally rebuild quicker and stronger than those without stable relationships and social conditions.

This connection between efficacy and economics is where the line blurs between disaster relief and social service support. Mental health workers should be prepared to focus a significant portion of their work with individuals, families, and communities who, due to lacking both economic and social/emotional resources pre-disaster, find their circumstances exacerbated post-disaster. Hobfoll et al. (2007) recommend mental health programs collaborate with development initiatives to promote better living and working conditions to enhance life choices and chances for better resiliency and life quality. There must be special care taken not to disempower individuals, families, and communities by removing them from the decision-making process. Crucial to this belief of positive outcome is a sense of control (Taylor, 1983).

To illustrate these points, a focus group was conducted in Sea Bright, New Jersey—another very impacted area—8 months after Hurricane Sandy. At this focus group, community members spoke about how they did not have a clear understanding of the information that was available regarding the rebuilding effort. They expressed frustration and a feeling of powerlessness. Many community members were still displaced and spoke of how the town was moving on without them, and they had little access to information because they did not live in the town at present. In addition to losing their homes, they also had lost their sense of community. Many recreational sites had also been destroyed including the recreation building, library, and many cafés and restaurants. There was no central place to gather and reunite with friends. There was no central place to get information in the town about rebuilding, zoning, grants, or procedures. One resident said she felt she had been a victim of the storm and also a victim of false hope and promises. Several community members stated that many agencies (community, governmental, and national organizations) were in Sea Bright immediately following the storm with many promises, but few have come to fruition. Many groups had written for grants and spoken on behalf of Sea Bright, but few had asked what the community members wanted. The process was not driven by the community but instead by organizations working on behalf of the community. This created a sense of further disempowerment and loss of efficacy (Findley, 2013). Although this focus group was held in New Jersey, it may well apply to many other areas following disaster.

Social support and connectedness is the fourth aspect. This connectedness with family and community is important for mental health purposes in this stage. There is evidence that PTSD incidents rise when the family structure is interrupted due to separation (McIntyre, 2009). This may occur due to shelter requirements, relocation in temporary housing, or family members not being geographically present when a disaster happens. To lower the risk to mental health, special attention should be made to reunite families and communities as quickly and sustainably as possible (McIntyre, 2009). Encouraging connectedness promotes problem solving, sharing of experiences, coping strategies, and a general sense of efficacy. Delay in this connectedness is a risk factor for PTSD. Key aspects in fostering social support are enhancing knowledge of types of social support, identifying sources, and learning how to build networks (Norris et al., 2002).

It is relevant to note that in building support networks, care should be placed on promoting individual self-worth. This is necessary to deter dependency on unhealthy or negative relationships as well as to protect from complacency and overusing supports. For those who have limited natural supports to build on, creating and fostering community supports can also be successful. These can include support groups, welcoming committees, councils, and recreational activities. Specific attention should be taken to protect vulnerable populations from being ostracized or targeted due to lack of resources. Cultural competence is also essential in this period. Culturally diverse and relevant groups should be accessible for traumatic reactions and effects since they are interpreted differently. There has been little systematically examined in relation to vulnerable populations and disaster mental health even though these groups are at a higher risk because of preexisting conditions and socioeconomic struggles. Disaster mental health is focused on the mainstream population with interventions targeted for their needs. Recommended action steps would be to not only train first responders in cultural competence but also to bring at-risk stakeholders to pre-disaster planning meetings and implementation sessions (NBSB, 2008). This can be considered a social justice issue to reduce the level of disproportionality in vulnerable populations in regard to negative outcomes in disaster mental health.

The last aspect of the framework for traumatic mental health resources is instilling and maintaining hope. Hope is often the first victim following a traumatic event. There is evidence that shows that those who maintain hope have less occurrence of PTSD (McIntyre, 2009). The loss of hope is also accompanied by a “shattered world view” (Hobfoll et al., 2007, p. 298). This was seen in the Sea Bright focus group when the belief in the insurance companies and governmental structures was altered (Focus Group, June 2013). People who have been paying for insurance and flood insurance for years found that the companies they had faith in were seeking loopholes to not pay for rebuilding. Equally, a firm belief in the state and federal governmental system to protect and assist had also been shaken when promises for grant funding left many people frustrated. People, who had never sought help from the government, were now asking for help. In addition for having to learn how to navigate through new bureaucracies, they felt embarrassed to ask for help and baffled to be told there was no help available (Focus Group, 2013).

Finally, the focus groups also proposed a list of questions that could be used for a functional assessment of services provided in the first month following a disaster; and many should be addressed prior to a disaster to have the community ready for a quick response. The questions proposed by the group are outlined in Fig. 9.1.

6 Role of Social Workers and Other Mental Health Workers in a Disaster

Social workers can be essential in many aspects of a disaster response protocol. Social workers institute research protocols and data collection to examine and reduce adverse conditions. They assess mental or physical health problems, identify high-risk groups, assess immediate health and resource needs, and locate resources. In addition, social workers can offer a sound management and community response. This includes creating disaster plans , communication systems, coordinating services, and generating resources that cross the disaster care continuum, from preparation (developing, renewing, and revising a current plan) to the event (supplying resources and support) through recovery and relief (reconstruction, repairing, and healing) (Galambos, 2005). Social workers engaged in direct practice will commonly see responses of fear, anger, and distress. The type of behavior will vary depending on the level of exposure to the disaster situations. Levels include primary (i.e. death of loved one, destruction of property, injured), secondary (i.e. eyewitnesses, rescue workers, those affected by community loss), and tertiary (i.e. overload of media) levels (Galambos, 2005).

Those who were displaced as a result of Hurricane Sandy showed twice as high levels of psychological distress than those who maintained their home (Focus Group, 2013). For those in the focus group, anxiety and panic disorders were more likely among those who were displaced, while adjustment disorders were highest among those who were able to remain in their homes. Recommended to reduce levels of anxiety, panic, and depression among those displaced is to establish a new sense of community, promote control over one’s life, and stabilize the social environment. Three key elements need to be in place prior to a disaster: preparedness of public health emergency rooms, communication among responders, and educational information for the public.

7 Community Mental Health

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) (Mitchell & Everly, 2001) was developed in the early 1980s as a psychosocial stress debriefing technique to occur for first responders within 72 h of a traumatic incident. The technique began to be utilized as the crisis intervention in communities following a disaster. There was general criticism of CISD as being nonresponsive to the needs of individuals affected by traumatic incidents. This critique led to the creation of psychological first aid (Macy et al., 2004). A further critique of CISD from a community-based perspective is the lack of increasing community-based capacity. This increased delivery necessitated the increase of community-based provider capacity. In addition, the WHO recommends local community-based mental health services as a best practice approach (WHO, 2012).

The Crisis Counselor Program (CCP) attempted to address the need to fill this capacity following Hurricane Katrina (Pribanic, 2009). There was widespread outreach by CCP and free community-based mental health resources; however, vulnerable populations still seemed to fall through the cracks. Even though many people returned to their pre-disaster mental health conditions within 2 years, vulnerable populations seemed to still be lingering in a post-disaster state; 8–10 % of people in a traumatic situation will develop PTSD-like symptoms (Pribanic, 2009).

The cause for many of these problems can be identified as lack of resources. Resources can be defined as both governmental and nonprofit organizational social services or natural community supports. These resources are often lacking due to loss of community and social structure, optimism, and control over one’s life. Among those at highest risk are poor people, women, young children, elderly, racial and ethnic minorities, and single parents. Exposure to constant stressors and competition for resources are strong predictors (Pribanic, 2009).

Since its inception, shortly after 1950, disaster management was tied to maintaining social order because officials feared a breakdown following a disaster event. Recent research shows breakdown happens when the crisis period is over and competition over limited resources increases. During the crisis event, people are most altruistic (Pribanic, 2009).

Current social theory focuses on social capital and the importance of social networks, reciprocity, group strength, and interpersonal trust (Patterson, Weil, & Patel, 2010). This theory leads to the creation a working definition of community. According to Patterson et al. (2010), when community is only a group of individuals based on geographic or superficial commonality, they lack both cohesion and ability to act together. This lack of cohesion forces the groups to become reliant on a system to make decisions for them. In contrast, a community structured around diverse types of civil societies (clubs, churches, organizations) can act as one entity for the greater good. The civil society-type community can be more effective than a removed county, state, or national governing body because these community structures are local, rapid, flexible, and adaptive. These types of communities are also the basis for community-based participatory initiatives since they are action and advocacy oriented and understand the connection and relationship between the community, organizations, and the government (Patterson et al., 2010).

8 Community Models of Resiliency

Community resiliency refers to a community’s ability to support itself through a crisis. Underserved communities are at a higher risk because of lack of resources (Wells et al., 2013). Most models for resiliency and engagement are top down, but disaster requires a 72 h response time that would require a grassroots approach. This condition requires partnership, communication, and community engagement that can improve access to resources and recovery. Grassroots community-driven models emphasize power sharing among participants with knowledge exchange to support partnerships. An example is the community-partnered participatory research model used in Los Angeles following major earthquakes (Wells et al., 2013). This is a three-stage initiative including vision (planning)/valley (implementation)/victory (dissemination). This model has long-term effects for the post-disaster community because it can be used to develop a pre-disaster program of community engagement.

The methodology starts with a community kickoff conference. The conference includes local volunteer agencies active in a disaster relief (VOAD), emergency response (ER) agencies, local government, community organizations, academic institutions, and community members. During the conference, three questions are asked:

-

(a)

What is your organization doing now to build community disaster resilience?

-

(b)

What challenges do you see in increasing this?

-

(c)

What would make your community more resilient?

The information gathered at the conference is utilized to form three working groups: information and communication, partnerships and social preparedness, and vulnerable populations. Each group would meet bimonthly for 6 months to discuss and develop recommendations for community resiliency interventions. These groups would follow critical consciousness guidelines. A discussion of the use of critical consciousness will be included later in this chapter. Typical ideas discussed in these meetings would be unfamiliarity with emergency protocol, lack of transparency, and leadership responses.

The next step for the community-partnered participatory research model, utilized in Los Angeles, is a community response conference. This conference would take place 6 months after the first and provide an overview of goals, summary of findings, presentations, and open discussions. This leads to a community resiliency plan that would include proposed action plans, ways of acquiring financial support through possible mini-grants, how to gain staff buy-in for community agencies, where to find resources, how to conduct trainings, and potential ways to outreach. A pilot program toolkit for participating community organizations to implement the community resiliency plan should focus on individuals and families. The last step of the model would be to convene for a final workshop that would review how the plan is working in action (Wells et al., 2013).

Smit and Wandel (2006) created a model to identify risk and vulnerability in a community. In the model, community engagement is highlighted and it is culturally adaptable for present and future conditions. Capacity will be evaluated in collective adaptability, coping capacity and resiliency. The model starts with the cause or current exposures and sensitivities. It then identifies the current adaptive strategies. The next step involves analyzing future needs. These future needs will include both future exposures and sensitivities and future adaptive strategies. The model ends with the adaptation of needs (Smit & Wandel, 2006).

8.1 Recommendations for a Community Toolkit

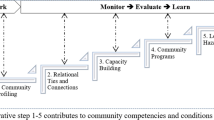

Toolkits are useful to address the key issues described above (Image 3 about here).

Among the major resources of a toolkit are:

-

1.

Individual and family disaster plan, supplies, communication, and next steps

-

2.

Vulnerable populations: how to prepare for kids, animals, disabled, seniors, mental health, and language barriers

-

3.

Community response teams: roles and responsibilities

-

4.

Neighbors: mapping local resources

-

5.

Nonprofits/faith-based/small businesses: disaster planning and survival guide

-

6.

Donating and volunteering: how and to whom to donate and where to volunteer

Training components may include:

-

1.

Psychological first aid: listen, protect, and connect

-

2.

Community mapping: identify strengths and risks and respond to emergencies

-

3.

Engagement strategies

-

4.

Develop leadership

-

5.

Train-the-train modules for responders and community staff

Potential evaluation questions when considering what to include in the kit include (Wells et al., 2013):

-

1.

What are the benefits?

-

2.

What are the processes?

-

3.

What are the barriers?

-

4.

What components are most effective?

-

5.

What are the costs?

-

6.

How do strength and risk factors shape the evaluation?

8.2 Disaster Mental Health Utilizing a Critical Consciousness Modality

While there are many types of models currently being used for disaster relief mental health, the vast majority still reflect a top-down approach. Disaster response models teach how to work in the community, how to identify early signs of PTSD, and how to maintain self-care, but the current pedagogy does not focus on context of situation, socioeconomic relevance, or cultural competence (West-Olatunji & Goodman, 2011).

Mental health professionals often lack both disaster preparedness skills and cultural competence training, which limit their effectiveness in responding to a disaster (West-Olatunji & Goodman, 2011). Cultural competence is necessary for a macro understanding of the crisis situation, whether it is a natural or a man-made disaster. By utilizing a critical consciousness framework, counselors are able to incorporate this broader understanding and build more authentic relationships (West-Olatunji & Goodman, 2011).

Critical consciousness is a praxis-based philosophy that draws on reflection and action. It requires the trainer to take a co-facilitating role with the student to create a teacher-teacher modality (Freire, 1994). While critical consciousness has primarily been used in education, the same concepts can be applied to social work and mental health practice following a disaster. Freire’s problem-posing structure can also be described as a cyclical process of listening, dialogue, and action which can be used in therapeutic group work. Through this praxis of reflection and action, group members are able to see connections between their personal problems and those of others which create a sense of shared purpose and unity (Carroll & Minkler, 2000). What is different in Freire’s approach is the removal of practitioner as leader. Instead the practitioner fills the role of co-facilitator on the same teacher-teacher level as everyone else. Freire’s model differs from conventional group work in that instead of focusing on the pathology of behaviors and helping people fit into the structures of society, critical consciousness seeks to change the structures of society to fit the people (Carroll & Minkler, 2000).

By following the pedagogy of critical consciousness, the first responder will enter a community not as an outside force that further disempowers the already victimized community, but instead as one who both has trust from the community and trust in the community to build a program that will best suit the needs of the community (Freire, 1994). With training in critical consciousness, the worker is able to gain awareness of the ramifications of potential actions in particular communities. They are able to shed their own preconceived notions of the best programs to create built on biases about the individual communities. Mental health becomes a social justice issue that is enhanced with cultural competence. By engaging in critical thinking, practitioners will be able to significantly collaborate with community members and other practitioners (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009).

A proposed seven-step disaster relief critical consciousness model mirrors the previously discussed in the community-based participatory action research model used in Los Angeles to encourage community response for pre-disaster protocols (Wells et al., 2013). Step one must address the practitioners’ biases. This would be considered an awareness stage (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). This stage also pertains to acquiring an understanding of cultural competency. It is necessary to understand one’s own cultural biases and the dominant universal biases that shape our cultural perspective before understanding of another’s culture can take place (McGoldrick, Giordano, & Garcia-Preto, 2005). Having a strong sense of cultural competence is important in disaster relief as practitioners will be going into culturally diverse areas and spending significant time with vulnerable populations. A lack of cultural awareness may aggravate problems due to the ignorance of the community’s cultural norms and potential mistrust based on political and socioeconomic historical problems (West-Olatunji & Goodman, 2011).

The second step is respect and value of the community members’ knowledge (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). This is shown in the mutual trust that the practitioner and the community have in each other. The community must trust the practitioner and buy-in to the program. But at the same time, it is absolutely necessary for the practitioner to trust that the community has the competence and worth to become a partner in the process (Freire, 1994). If the practitioner comes with a savior mentality (i.e. believing he or she is there to save the community single-handedly), the process will not be successful because the community members will still be objects in the disaster instead of subjects in their recovery.

Context, specifically of socioeconomic standards, is the next step in the critical consciousness framework (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). It is this step that is often forgotten in post-disaster program planning. Often there is a rush to bring services, including mental health services to a disaster site, and the context of the community is lost. There needs to be time to understand the nature of the disaster, if there had been other disasters in the community before, the demographic make-up of the community, the vulnerable populations, community strengths, and risk factors (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009).

The understanding of context will be used in the fourth step. Integration is how knowledge is transformed in guided action (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). The goal is to empower by creating a dialogue with the community to guide them in problem solving. The solution can only be reached with problem solving questions and not through dictating types of practice (Freire, 1994). The community should drive the needs and wants of the types of culturally competent mental health interventions needed for success.

Empowerment is the natural consequence and the next step of this type of intervention (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). By partnering with the community, engaging in dialogue, and understanding the wider socioeconomic implications, the community members are able to move from objects to subjects and masters of their own situation (Freire, 1994). The sixth step is praxis, reflection and action together (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). It is here where the community members are now empowered and has the tools to move forward with their own recovery.

The final step is transformation (Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2009). The community members are able to recover and now possesses the tools to help others in their recovery as well as face future disasters. The World Bank (n.d.) defines a disaster as a serious disruption in the function of the community, where the community cannot recover with its own resources. This type of critical consciousness process may mitigate the reoccurrence of disaster situations by strengthening communities.

9 International Approach

International disaster relief utilizes social capital to rebuild after a disaster to enhance capacity and ensure social development (Mathbor, 2007). The level of social capital is measured by the level of solidarity, social cohesion, social interactions, and social networks. This practice focuses on community comprehension, participation, organization, and control. The basis is to build trusting relationships, mutual understanding, and shared actions to bring individuals, communities, and institutions together for the purpose of generating opportunities and resources in the community following a disaster (Mathbor, 2007). International experience has shown that disaster trauma effects are first felt and responded to by the community. Responses are most effective when enacted by community. Investment in community-based preparedness measures saves lives and property. Local communities know their own strengths and weaknesses and will have the most relevant information. Community focus facilitates the knowledge of vulnerable populations (The World Bank, n.d.).

According to the World Bank, disasters are unresolved problems in development. Disaster Risk Management (DRM) is a systematic approach of using decisions, organization, operational skills, and capacity to institute policies, strategies, and coping skills to lessen the impact of natural or technological disaster. In the risk reduction period, hazards can be managed and reduced by building community resiliency. During the response period, DRM determines what kind of relief is needed and how it is administered. Lastly, in recovery, communities are linked to development agencies with the goal of understanding the pre-disaster struggles. DRM is closely linked with community-driven development (CDD) to transfer the control of development from outside agencies into the hands of the affected communities (The World Bank, n.d.).

The United Nation’s (UN) International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) is a best practice for developing countries (UNDP, 2004). ISDR is based on the concept that disaster reduction must be a national, institutional policy, have an early warning system, increase safety and resiliency through education, reduce risk factors, and strengthen the ability to respond. The UN’s approach calls for local communities to drive the program (UNDP, 2004). Communities must define problems, decide solutions, implement strategies and evaluate results, build linkages between communities and governments, run environmental analysis and scan, incorporate the needs and views of the vulnerable, focus on livelihood security, provide information, education, and communication, and have an accountability system in place. The World Bank recognizes that top-down practices are insufficient to meet the disaster-related needs of poor and vulnerable people because they are less able to identify community dynamics, perspectives, and needs (The World Bank, n.d.).

World Bank-supported programs have a three-step process to build social capital in underdeveloped communities in all stages of disaster planning and preparation, response, recovery, and relief (Mathbor, 2007). Programs are first designed to bond with communities. This includes using social integration, cohesion, communication, collaboration, fostering leadership qualities, aiding members through recreation, religious and spiritual gatherings, political and institutional affiliation, economic interests, and psychological and social supports. The second step is to build bridges between and among communities by engaging in coalition building. And, the third step is to link communities with financial and public institutions. This is accomplished by assisting in mitigating consequences following a disaster and mobilizing community resources, expertise, professionals, and volunteers.

Crucial to each of these stages is education, transparency, and access to information. The World Bank recommends training volunteers all year to generate leadership and management skills and build solidarity. This helps build trust and to understand all resources in a community. Utilizing local media aids in the community’s engagement in public awareness. International social workers are well connected to their community, are familiar with resources, encourage leadership potential, and are well versed on ideas on a micro, mezzo, and macro level (Mathbor, 2007).

The WHO has several core principles for international disaster response (IASC, 2007). These include human rights, community participation, a do-no-harm philosophy, building on available resources, and integrating social systems. Their programs facilitate a four-tiered multilayered support system. This system has a base of basic services and security, followed by community and family supports. Nonspecialized, institutional-based supports follow, with specialized services as the final tier. The vulnerable populations they consider at highest risk are women, children, elderly, extremely poor, refugees, people with past trauma, those with mental illness or with developmental disabilities, who are institutionalized, those with social stigma, and those who might be susceptible to human rights violations.

The goal is to apply this international framework to a domestic disaster response. This can be accomplished by building a community Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) unit of local stakeholders. This unit will coordinate assessment, collect and analyze key information, and make ethical and participatory assessments. These assessments will include those with mental illness, assurance of adequate supply of psychotropic drugs in emergency, use and training of PFA, dissemination of information about available mental health services, ability to work with existing structures, and the involvement in interagency meetings. The MHPSS team will be able to identify resources in local community, engage in community partnership participatory action, support community initiatives, support efforts for those at great risks, provide training, and use advocacy techniques.

10 Community Efforts

Keeping the community resilient takes effort on the part of the community as well as participation from the individuals. Advocacy efforts have been discussed as one strategy to bolster community resiliency. Braun-Lewensohn and Sagy (2014) report that there is a variance in how rural versus urban communities cope in times of violence, and in this case, missile strikes in Israel. They found that those living in rural communities were more resilient than those in urban environments, based on the theory of connectedness among individuals and communal resources in smaller environments; these connections and resources helped to reduce anxiety.

Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, and Pfefferbaum (2008) state that communities can demonstrate effective functioning and adaptation following disasters. This coping relies on “stress reactions, adaptation, wellness, and resources dynamics” (Norris et al., 2008, p. 127). An example of a way to promote community resiliency is evidenced through a project that brought together researchers and community members from Israel and the United States to develop what psychosocial educational materials could be distributed as both a preventive measure prior to disaster or traumatic events or after the fact to help support recovery. Two of these documents are provided as appendices to this chapter (Appendices 9.1 and 9.2). The complete set of the materials are available in English, Arabic, Hebrew, and Russian at http://www.newpaltz.edu/idmh/resources-/usaid.html. These materials were developed by researchers and clinicians from the State University at New Paltz, Ben Gurion University, and Rutgers University through a grant funded by the United States Agency for International Development West Bank/Gaza to work with partners in the Middle East to develop a series of psychoeducational materials to help residents of Gaza, the West Bank, and Israel to cope with traumatic experiences.

11 Conclusion

The natural progression of disaster relief mental health services, over time, moves from a top-down rigid approach to a grassroots community participatory plan for sustainability. Any protocol should encompass a theoretical framework of empowerment as a comprehensive and multidimensional approach. Empowerment theory “promotes social justice and advocacy, addresses the role of social power, normalizes difference and occurs on personal, interpersonal and political levels that encompass power relation” (Garcia, 2009, p. 87). It is an approach to use with immigrants and other disenfranchised people for several reasons. It takes into consideration the social, economic, and political forces that were at play in the choice to immigrate, as well as life in the new environment (Reznik & Isralowitz, 2016). Historical perspectives, race, class, and gender are key. It is an approach based on social justice and advocacy (Garcia, 2009) that is concerned with collective action, political engagement, and creating new ways to help people care for each other (Taylor, 1999).

Action is essential for true empowerment. When people are educated using critical consciousness, they move forward to increase their personal or community power in a way that uplifts themselves and their communities. This includes collective areas of concern, experience, and preference. Group consciousness is the understanding of status and power within the group and within the group’s place in society. Self and collective efficacy is the belief that a person or community has the ability to effect change in their lives (Gutierrez, 1995).

The empowerment and structural approach does not omit the importance of the interaction between the person and the environment as the psychodynamic and systems approach often do. The psychodynamic and systems framework focus heavily on the individual and how that individual can adjust and cope with their world. Cultural competence in these approaches is used as a basis of understanding the individual and how they interact with their surroundings, but in a way of acculturating the individual into mainstream society. The empowerment approach meets the individual where he or she is and works with individual strengths to not necessarily change them, but to aid in the understanding of perception; how individuals perceive and how they are perceived. They can then move forward with a new understanding of the society of which they are a part. It is important to note that personal responsibility is not removed in the empowerment theory, but instead encouraged.

The final piece of the community-level intervention is the concept of self and collective efficacy (Gutierrez, 1995). This can be compared to Bisman’s concept of belief bonding, where the social worker must believe in the inherent worth of the person and their ability to succeed (Bisman, 1994). Self and collective efficacy though is the person and communities’ belief in their ability to affect the desired change (Gutierrez, 1995). It again is the difference between the psychodynamic or systems approach and the empowerment approach, where in the former the change agent must believe in the change and in the latter the person must believe themselves capable of facilitating change. This will begin with the awareness of group identity and continue through small victories of change.

12 Future Directions

With a look toward the Middle East, it is important to end this chapter with findings noted by several researchers. Bleich et al. (2006) observed that following 19 months of constant exposure to terrorism, they found indicators in their study of 902 households; extreme levels of psychological disorder did not develop in the majority of those households, which may be related to adaptation and accommodation. However, Bleich et al. 2006 found that after 4 years of constant terrorism, there have been mixed levels of coping, with some groups being disproportionately impacted over others. For example, those with fewer resources, such as the Arab population in their study, those less educated, and immigrants, all demonstrated higher levels of distress. Resilience to stress is an ability of some, yet it is the constant stress, particularly for those with fewer resources that should attract attention for future work.

References

Bisman, C. (1994). Social work practice: Cases and principles. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Chapter 4.

Bleich, A., Gelkopf, M., Melamed, Y., & Solomon, Z. (2006). Mental health and resiliency following 44 months of terrorism: A survey of an Israeli national representative sample. BMC Medicine, 4(1), 21. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-4-21

Braun-Lewensohn, O., & Sagy, S. (2014). Community resilience and sense of coherence as protective factors in explaining stress reactions: Comparing cities and rural communities during missiles attacks. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(2), 229–234.

Carroll, J., & Minkler, M. (2000). Freire’s message for social workers: Looking back, looking ahead. Journal of Community Practice, 8(1), 21–36.

Dickstein, B. D., Schorr, Y., Stein, N., Krantz, L. H., Solomon, Z., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Coping and mental health outcomes among Israelis living with the chronic threat of terrorism. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(4), 392–399.

Farberow, N. L., & Frederick, C. J. (1978). Training manual for human service workers in major disasters. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from http://xxx.icisf.org/news-a-announcements/31/35-psychological-recovery-from-disaster

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2012). Retrieved from http://www.fema.gov/public-assistance-local-state-tribal-and-non-profit/recovery-directorate/crisis-counseling

Findley, P. (2013). Stakeholder engagement report: Social services sector climate change preparedness in New Jersey. New Brunswick, NJ: New Jersey Climate Adaptation Alliance.

Findley, P., Indart, M., & Kley, R. (2015, October). Hurricane Sandy: The behavioral health response. Final Report to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Freire, P. (1994). The pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Publishing Company.

Galambos, C. (2005). Natural disasters: Health and mental health considerations. Health & Social Work, 30(2), 83–86.

Garcia, B. (2009). Theory and social work practice with immigrant populations. In F. Chang-Muy & E. Congress (Eds.), Social work with immigrants and refugees (pp. 79–101). New York: Springer.

Goodman, R. D., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2009). Applying critical consciousness: Culturally competent disaster response outcomes. Journal of Counseling and Development, 87(4), 458–465. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00130.x

Gutierrez, L. M. (1995). Understanding the empowerment process: Does consciousness make a difference?. Social Work Research, 19(4), 229–237.

Hobfoll, S. (2012). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. Oxford Handbooks Online. Retrieved February 12, 2016, from http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195375343-e-007

Hobfoll, S. E., Canetti-Nisim, D., & Johnson, R. J. (2006). Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and defensive coping among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 207–218.

Hobfoll, S., Watson, P., Bell, C., Byant, R., Brymer, M., Friedman, M. J., et al. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry, 70(4), 283–315.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hac/network/interagency/news/iasc_guidelines_mental_health_psychososial.pdf

Macy, R., Behar, L., Paulson, R., Delman, J., Schmid, L., & Smith, S. (2004). Community-based acute post traumatic stress management: A description and evaluation of a psychosocial intervention continuum. Harvard Review Psychiatry, 12(4), 217–228. doi:10.1080/10673220490509589

Macy, R. & Solomon, R. (1995). Psychological first aid. International Trauma Center. Retrieved from www.internationaltraumacenter.com

Macy, R. & Solomon, R. (2010). School-agency-community-based post traumatic stress management with psychological first aid. Basic Course Manual, International Trauma Center, Boston.

Mathbor, G. M. (2007). Enhancement of community preparedness for natural disasters the role of social work in building social capital for sustainable disaster relief and management. International Social Work, 50(3), 357–369.

McGoldrick, M., Giordano, J., & Garcia-Preto, N. (2005). Ethnicity and family therapy. New York: Guilford.

McIntyre, J. (2009). Federal disaster mental health response and compliance with best practices. Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University. Retrieved from http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/2290/Jody%20McIntyre%202009.pdf?sequence=1

McIntyre, J., & Nelson Goff, B. (2011). Federal disaster mental health response and compliance with best practices. Community Mental Health Journal, 48, 723–728. doi:10.1007/s10597-011-9421-x

Mitchell, J. T., & Everly, G. S., Jr. (2001). Critical incident stress debriefing: An operations manual for prevention of traumatic stress among emergency services and disaster workers (3rd ed.). Ellicott City, MD: Chevron.

National Biodefense Science Board (NBSB). (2008). Disaster Mental health recommendations: Report of the disaster mental health subcommittee of the national biodefense science board. Retrieved from http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/boards/nbsb/Documents/nsbs-dmhreport-final.pdf

National Institute of Mental Health. (2002). Mental Health and Mass Violence: Evidence-based early psychological intervention for victims/survivors of mass violence. A Workshop to Reach Consensus on Best Practices. NIH Publication No. 02-5138, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981—2001. Psychiatry, 65(3), 207–239.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150.

Patterson, O., Weil, F., & Patel, K. (2010). The role of community in disaster response: Conceptual models. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(2), 127–141.

Perliger, A., & Pedahzur, A. (2015). Counter cultures, group dynamics and religious terrorism. Political Studies, 64, 297–314. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12182

Pribanic, K. (2009). Reproductions of inequality: An expanded case study of social vulnerability to disaster and post-Katrina assistance. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY.

Reznik, A., & Isralowitz, R. (2016). Immigration, acculturation and drug use. In R. Isralowitz & P. A. Findley (Eds.), Mental health and addiction care in the Middle East (pp. 109–123). New York: Springer.

Silver, R. C., Holman, E. A., McIntosh, D. N., Poulin, M., & Gil-Rivas, V. (2002). Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(10), 1235–1244.

Smit, B., & Wandel, J. (2006). Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global environmental change. Human and Policy Dimensions, 16(3), 282–292.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association (SAMHSA). (2007). Tips for talking with and helping children and youth cope after a disaster or traumatic event. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/dtac/docs/KEN01-0093R.pdf

Taylor, S. E. (1983). Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1161–1173.

Taylor, Z. (1999). Values, theories and methods in social work education: A culturally transferable core? International Social Work, 42(3), 309–318.

The World Bank. (n.d.). Building resilient communities: Risk management and response to natural disasters through social funds and community driven development operations. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSF/Resources/Building_Resilient_Communities_Complete.pdf

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2004). Reducing disaster risk: A challenge for development. New York: UNDP/Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery.

Wells, K. B., Tang, J., Lizaola, E., Jones, F., Brown, A., Stayton, A., et al. (2013). Applying community engagement to disaster planning: Developing the vision and design for the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience initiative. American Journal of Public Health, 103(7), 1172–1180.

West-Olatunji, C., & Goodman, R. (2011). Entering communities: Social justice oriented disaster response counseling. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 50(2), 172–182. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2011.tb00116.x

World Health Organization. (2012). WHO quality rights toolkit: Assessing and improving quality and human rights in mental health and social care facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70927/3/9789241548410_eng.pdf

World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation and World Vision International. (2011). Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers. Geneva: WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 9.1: Coping with Traumatic Experiences

Stressful events are part of life for everyone, but sometimes experiences are so difficult that they cause strong emotional reactions that can take time to recover from. This is true for everybody, no matter how strong they are, so people should not feel ashamed or embarrassed if they’re having trouble coping with a bad event. The good news is that most people do feel better as time passes, and there is a lot you can do to help yourself and those you care about to recover more quickly.

Some traumatic experiences happen one time and then they are over. Still, because they are so frightening personally or they cause such serious losses (e.g., loss of a loved one or a home), it is common and natural for people to have intense negative feelings that can last for some time.

Many people in some communities are also exposed to repeated threats or losses and to ongoing uncertainty or fear about when the next event will happen. It is even harder to start to recover when you do not really feel safe—but again, there are steps you can take to help cope with your emotions in a healthy way.

1.1 Typical Reactions to Stress and Trauma

Whether you’re dealing with a single event or with chronic stress, the following are some common responses people often experience after trauma. Often we do not realize these bad feelings are understandable reactions to the stressful event, so being aware of why we feel the way we do now can reassure us that we will not always feel like this.

Emotional reactions | Behavioral reactions |

• Sadness | • Avoiding reminders of the event |

• Fear | • Sleeping too much or too little |

• Guilt or shame | • Eating too much or too little |

• Numb | • Inability to relax |

• Anger or resentment | • Isolating yourself |

• Overwhelmed | • Increased conflict with others |

• Irritable | • Working too much |

Cognitive reactions | Physical reactions |

• Forgetfulness | • Jumpiness, easily startled |

• Poor concentration | • Too much caffeine, nicotine, alcohol |

• Disbelief | • Breathlessness, lightheadedness |

• Preoccupied | • Stomach upset |

• Poor problem solving | • Muscle tension or pain |

• Blaming yourself or others | • Headache |

Spiritual reactions | |

• Increase or questioning of faith | |

• Change in religious practices | |

• Struggle with questions about meaning, justice, fairness | |

All of these reactions can make you and those around you feel terrible. People who have been through a traumatic experience often are afraid they will feel this way forever, but that is usually not the case.

1.2 What Can You Do When Stressful Things Happen?

Sometimes we have the ability to change the source of the stress, but often we do not. Still, even if we do not have much power to change the situation, we do have power over what we can do to make ourselves feel better.

Think about what you have done in the past to help yourself during difficult times and whether those actions could help now. Many people find the following to be helpful, but what is most important is to choose actions that work for you personally. Remember that if you make suggestions to friends and family, what works for them may be very different than what works for you. Consider:

-

Turning to family or friends for support and comfort

-

Praying or following spiritual practices

-

Taking care of your health by eating well and getting enough sleep and exercise

-

Listening to music or doing other calming activities you enjoy

-

Getting physical activity

-

Helping others in your family or community who experienced the traumatic event

Some actions might make people feel better at first but have a negative effect later on. Try to avoid:

-

Eating or smoking too much

-

Using alcohol or drugs to dull your feelings

-

Isolating yourself from others

-

Watching too much television

-

Sleeping too much or too little

-

Bullying people around you

-

Blaming or scapegoating people or groups who were not really responsible for the event

1.3 Where Can You Get More Help?

As time passes after a traumatic experience, people usually start to feel better, especially if they are using good coping practices. Still, this can take longer than we expect, especially if the stress is ongoing, and sometimes it is useful to seek out more information or to talk to a trained helper who can provide more support.

These materials are made possible by the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of these materials are the sole responsibility of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at SUNY New Paltz and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

Appendix 9.2: Help for the Helpers, Caring for Yourself When Assisting Others

Helping members of your community who have been through a traumatic experience can be very rewarding, but it also can take a toll on you both personally and professionally.

While it is important to recognize the occupational hazards of assisting others (especially regarding working with patents who are trauma survivors), it is also important to remember that through regular self-care practices, the benefits of trauma work can outweigh the potential risks.

How well do you take care of yourself? You can only be a competent helper if you are not stressed out personally, so your commitment to self-care and wellness is actually an ethical and professional responsibility. The following are some ways to make sure you are taking care of yourself so you can continue to take care of others.

2.1 Rewards and Risks of Helping

Each helper experiences a unique combination of rewards from this kind of work. These rewards are part of the inner positive factors that motivate us to practice in one of the helping occupations. Among the positive feelings a helper can experience following his/her work are personal growth and self-awareness, a sense of emotional connection with survivors and the community, and pride in overcoming difficult challenges during times of crisis and chaos. What is it that keeps YOU motivated to help those in need? One source of self-care is to be aware of the rewards and satisfactions you receive from this work—and to be conscious of signs that the costs of caring are starting to outweigh those rewards.

Two main occupational hazard helpers should be aware of:

-

1.

The first one is burnout or compassion fatigue (a term more specific to the helping professions in the field of trauma survivors). Workers continuously overextend their capacity to aid others and become emotionally exhausted by the work. This can limit their ability to be effective helpers, but it can usually be cured by taking a break and practicing effective coping methods like those described below.

-

2.

The second main hazard, referred to as vicarious traumatization or secondary traumatic stress, can be far more serious. In this case, intense or repeated exposure to clients’ stories of traumatic experiences can impact the helper as if he or she suffered the traumatic event personally. This can take a serious emotional toll, changing one’s beliefs about fairness, justice, or good and evil in the world. Fortunately good self-care can help prevent this reaction from occurring.

Main risk factors in the helping professions are:

-

A large amount of exposure to trauma and bereavement

-

The trauma experienced by patents (e.g., injuries, death, or grotesque images or sounds) that are passed on to the helpers

-

Working with children who are trauma survivors

-

The many chronic (ongoing) stressors at the agency or private level

-

Helpers having their own unresolved trauma or grief reactions from current or past losses

-

Feeling helpless to assist others or an inability to acknowledge successful interventions (they can be major or minor ones)

In the event of large-scale disasters, or in cases of ongoing exposure to terror attacks, helpers often need to tolerate a great deal of ambiguity and uncertainty. In many cases, you may not know the long-term outcome of contact with those you are trying to help. This can add to professional stress. In such events, try to remember the phrase from Jewish tradition:

You are not responsible for finishing up the work,

and you are not free to evade it as well. (Avot, b, 18)

Warning signs for occupational hazards:

Emotional | Health (somatic) | Behaviors | Workplace |

|---|---|---|---|

• Anxiety | • Headaches | • Sleep changes | • Avoidance |

• Powerlessness | • GI distress | • Irritability | • Tardiness |

• Sadness | • Fatigue or exhaustion | • Hypervigilance | • Absenteeism |

• Helplessness | • Susceptibility to illness | • Appetite changes | • Lack of motivation or imitative |

• Depression | • Muscle aches | • Substance abuse | |

• Mood swings |

Relationships | Thoughts | Spirituality |

|---|---|---|

• Withdrawal/isolation | • Disorientation | • Loss of purpose |

• Decreased intimacy | • Perfectionism | • Anger with your God |

• Mistrust | • Problems concentrating | • Loss of faith |

• Misplaced anger | • Thoughts of harm | • Questioning meaning/purpose of life and beliefs |

• Overprotectiveness | • Rigidity | • Loss of belief in humanity |

• Regression to rigid, maladaptive thinking, and behaving patterns from your past |

-

In addition to the signs listed above, other warning signs include a loss of sense of humor, being unable to balance your personal life and work, and/or thinking you cannot be replaced.

-