Abstract

In the introductory section of this book, it was beneficial not to distinguish between self-chosen risk, such as an investment, and risk coming to a risk owner from the surrounding world.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

In the introductory section of this book, it was beneficial not to distinguish between self-chosen risk, such as an investment, and risk coming to a risk owner from the surrounding world.

This is because a risk owner experiences risk in the same way—no matter its source. The risk owner will experience risk as suddenly arising financial obligations. To a risk owner with limited access to reserve capital, it is thus of academic interest only whether the problems that materialize have this or that origin.

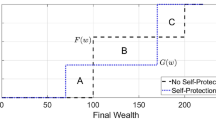

As described in the section on moral hazard , shifting responsibility from one risk owner to another may mean that a risk owner changes his behaviour. If a risk owner takes out insurance, the person may become more careless when it comes to preventing damage because the risk owner will no longer be hit as hard by the consequences of the risk if it materialises.

In addition to the moral hazard, there is another issue involved. It concerns the question of the extent to which a risk owner, be it a company or a citizen, exposes himself or itself to risk of his or its own accord.

You will not always take out insurance against such risk. And if the government offers to bail out risk owners in trouble because of a self-chosen risk, it really becomes risk free for risk owners to assume risk. This is a dangerous situation because some people might exploit it.

Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish between risk as an existential premise and risks actively incurred of one’s own accord. However, this distinction is only relevant when we want to look at government intervention in risk events.

As long as we are looking at the value of market-based insurance and the value of the risk owner’s capital, no distinction is required. The value of having reserve capital or insurance to protect a risk owner against structural risk costs is independent of the source of the sudden risk cost.

However, it is clear that when you consider whether to intervene to help a risk owner who is in a red phone situation, you might refrain from intervening if the situation has resulted from a risk taken by the risk owner of his own accord.

It is important to remember that we have never previously considered intervening to alleviate risk owners’ sudden risk costs in order to maintain their productivity and secure low risk costs in society. This is a new way of thinking and a new tool that may be taken into consideration simply by adding structure to the description of risk.

When risk owners have been bailed out in the past, it has mainly been a merciful act or for fear of the consequences of a bankruptcy. The latter is the basis for establishment of the government’s safety net protecting banks and other financial institutions. We know from experience with safety nets for banks that the fact that we are thus establishing a system which may be abused is a real reason to worry. Worrying about abuse of the government’s rescue of banks has been a topic of discussion for many in the media.

Conversely, very few people probably find that the sickness benefit system has been abused, even if it is free and actually resembles government intervention to alleviate sudden risk costs. The difference is that, from an overall perspective, illness is not self-chosen. Furthermore, illness has such big personal consequences that the fact that treatment is free does not induce more people to get ill.

On the other hand, it is clear that when we face a self-chosen financial risk in its purest form, we do have a challenge when we establish a system that enables government intervention.

The solution is thus not to try and create an extreme, risk-free society, which would be impossible, but selectively to review the possibilities of making a financially rational effort. It may well be that fields can be identified where government intervention towards self-chosen risk is in order, provided it is understood that the purpose is to minimise structural risk costs in society in general.

A case in point could be a large building contractor who has to take risks in order to operate in the construction market. Such companies occasionally find themselves in situations where a risk has materialized and they face a likely bankruptcy. Building contractors make a living from assuming risk. They are also exposed to a great many risk and uncertainty factors beyond their control—such as sudden regulatory or labour-market changes, crises, and other macroeconomic movements.

However, building contractors take part in deciding which contracts they will enter into with clients. In these contracts, they can take part in delimiting their own risk. In addition, they exert a lot of influence over many risk factors, such as the technical risk involved in performing a given piece of work.

The conclusion in traditional risk theory has been that we cannot save a firm of building contractors. They have to go bankrupt if necessary. However, with knowledge of the structural risk cost, it does not have to be this way.

The reason is not to be found in the structure of the firm of building contractors, but in the many structures with which the firm cooperates. When an enterprise such as a firm of building contractors goes bankrupt, this means that the enterprise cannot fulfil its commitments to customers and suppliers. The bankruptcy situation itself includes recognizing that the enterprise’s business partners and customers will experience sudden capital requirements. A subcontractor may have performed work on an assignment, but not yet received payment. When this payment never comes, the subcontractor will have to get the money elsewhere because he has to pay his employees for their work. A customer who has made a prepayment for an assignment that ends up not being carried out experiences a sudden loss, which may mean that he has to procure capital elsewhere, resulting in unknown financing costs resulting from the suddenly incurred cost.

It is thus absolutely certain that the bankruptcy of a major firm will lead to large, sudden, extra costs for a great many players in society, and no one can predict what the extra financing cost of these added costs will be. It is the unknown cost of financing suddenly arising capital needs among the contractor’s subcontractors and customers that poses a problem and an unwanted cost to society. The contractor’s bankruptcy in itself is not the problem.

One solution could be to apply the knowledge we have gained in recent years from bailing out banks to also bailing out other companies. Bailout might not be the right word, because the solution I am referring to does not involve saving the firm but rather closing the firm down in a controlled manner.

When talking about closing down a firm in a controlled manner, I refer to the process whereby all viable commitments are completed under government ownership. Only when the activities have been finalized is the company closed down.

In Denmark we have experience with this type of controlled shutdown of banks. We had a case of two banks, Amagerbanken and Roskilde Bank, which were facing bankruptcy. They went bankrupt and were closed down. However, this was done by the government taking over these companies and ending activities that could be ended while continuing activities that had to be continued until they could be ended. In this entire process, the former owners of the banks gained nothing, as the activities were managed under governmental ownership, which is an important point and the reason why such a process does not promote moral hazard among enterprise owners. The shutdown of the bankrupt company was a slow process; looking at the sum of the sudden capital needs passed on to other players and thus looking at the potential financing cost of these sudden capital needs, this is a much cheaper way of doing it than if you were to close down the company overnight, as is still practised for non-financial companies that go bankrupt.

It may well turn out that, going forward, governments will have an incentive to intervene on the behalf of more companies facing imminent bankruptcy than is the case today, when governments only utilise the opportunity to intervene in the case of financial institutions in some countries, depending on national legislation. If the intervention concerned is in the form of a controlled shutdown, this will have a positive macroeconomic effect; however, this must be compared with the cost of a slow, controlled shutdown process. It is not unlikely that from a macroeconomic viewpoint, the net result is positive in many situations. Depending on the design of such a system, there would, however, be cases of speculation against the system, even if it is difficult to speculate in regard to the closing down of a company—i.e., a situation in which the company is not bailed out, and the former owners of the company gain nothing from choosing a controlled shutdown over a dramatic crash-and-burn shutdown.

Speculation in bailing out companies occurs more frequently in cases where the goal of intervention is the continued survival of the company, and, as stated, this is not the solution suggested in this book.

The question of whether we are talking about self-chosen risk or risk coming from the surrounding world is of significance when we discuss government intervention and the role of the government when it comes to creating ideal growth conditions for risk owners in society.

When risk is self-chosen, it becomes more difficult to intervene. However, self-chosen risk does not have to exclude all kinds of government intervention, as long as higher demands are made as to how the government handles this task.

The Future and Structural Risk Cost

When we are able to describe the existence of the structural risk cost, the big question is: How does this change the government’s task vis-à-vis the population?

Nobody has any doubt that the government’s primary role is to provide safety, security, and stability for the population because this increases risk owners’ prospects for creating growth. Only on these conditions will risk owners dare to venture into long-term investments. Who can be bothered to build a good house if there is war, and we risk that what we build today will be destroyed or taken away from us tomorrow?

Ensuring society’s safety, security, law, and order are fundamental tasks for the government. Within this framework, the market economy can thrive, and people will dare to make long-term investments.

However, apart from national safety, security, law, and order, the government’s authority and tasks towards the population are more doubtful. All other tasks require the collection of more taxes from the population to finance such assignments, and that is not always looked positively upon by the taxpayers. The clearest statement of this point probably comes from Frédéric Bastiat , a French economist who did his work in the period after the French revolution:

All we have to do is to see whether the law takes from some what belongs to them in order to give it to others to whom it does not belong. We must see whether the law performs, for the profit of one citizen and to the detriment of others, an act which that citizen could not perform himself without being guilty of a crime. Repeal such a law without delay. … if you do not take care, what begins by being an exception tends to become general, to multiply itself, and to develop into a veritable system. (Bastiat 1848)

Bastiat is considered one of the founders of liberalism ; the basic idea in his work is that the government should not interfere in anything but defence and security. All other attempts to collect taxes from one person to give it to another person are wrong and lead to corruption of the state. Bastiat called it “legal theft” when the government gave itself the right to take money from one person and give it to another.

The central concept of liberalism is that the individual person should keep as many resources to himself as possible in order to have a bigger chance of achieving growth and wealth; this has remained unchanged since Bastiat , even if subsequent liberal economists have often been less extreme than Bastiat.

Milton Friedmann , who won the Nobel Prize for economy, wrote his book Capitalism and Freedom in 1962 (Friedman 1962). In his work, Friedmann also argued that the government should guarantee law and order as well as protect property rights in addition to a few additional points concerning the security of currency. Here, too, we thus see the discussion of what the government’s tasks are as well as the financial argument that the tasks should largely be restricted to security, law, and order. It should be mentioned that Milton Friedmann criticises John Meynard Keynes ’ work and the interpretations of Keynes’ work, because Friedmann is opposed to the government interfering in the market economy.

However, the emergence of the structural risk cost challenges the limitations on the role of the state as suggested by current liberalists, despite it being easy to characterise the structural risk work as a liberalistic approach aimed at creating the best possible basis for economic prosperity for the individual, whether this is a person, a company, or any other structure of society.

The structural risk cost described in this book has been proved by way of arguments and experiments, and this risk cost is relevant to growth in society. It indicates the existence of a national growth potential that can only be activated through additional government involvement, which is in stark contact to the basic thinking of the liberal economist.

Classic liberal thinking only generates growth up to a certain level. If you imagine a liberal society where the government is not working actively to protect citizens against sudden, significant costs, such a society’s ability to grow will be hampered, and in the longer term this society will lose out when competing against similar societies where the government fights the occurrence of sudden costs actively and cost efficiently. When the government actively fights sudden, significant costs for citizens in society, risk costs will decline and long-term investments will have better conditions.

Given this realisation, it now becomes a central role for the government to ensure that citizens have the best possible conditions for long-term investments. This is a role that must be taken seriously. We have seen in the latest financial crises that risk may have serious consequences for citizens. Consequently, the governments that today only secure citizens’ rights to law and order and property rights are governments which are not utilizing the potential of their citizens to create and implement long-term investments. These are states where a group of citizens actually does not have the same conditions as other, better-off groups in the population.

As a point of curiosity, it can be mentioned that for many years Denmark was called an economic bumblebee. The name was used as a parallel to the bumblebee, which in theory cannot actually fly but nevertheless does. This was the feeling about the Danish economy for a period. Denmark had, and still has, a very high level of taxation. Yet for a long period Denmark has been able to generate very high growth rates. Denmark has been able to grow even if the majority of economists thought that growth would be created by giving individuals their own money, thereby stimulating demand.

It is in fact very likely, although of course not documented, that Denmark actually had a highly beneficial government model in that period and that the high tax pressure provided ideal conditions for long-term investments, which has brought Denmark forward. Naturally, additional analyses will be required to find the precise significance of the structural risk cost to national growth, but if it does have major significance, this could lead to big changes in the way we perceive the role of the government.

If we assume that this significance is important and big, then a society in crisis cannot necessarily be stimulated to obtain growth the way Keynes proposed because stimulation can have a negative effect on the structural risk costs, causing growth to subside. It will be like filling a bucket that has a hole in the bottom; there is a short-term effect, but after a while the bucket is empty again.

If you want to generate growth in a country where the significance of the structural risk cost is high, you have to take a look at the equation of society’s structural risk costs and reduce the factors that can be reduced. A massive effort must be made to protect private individuals against sudden, unexpected, large costs. Only under these conditions will the population be competitive and capable of creating growth in society. Only under these conditions does it make sense to carry out stimulating measures in the country, as you have a balanced growth model focusing both on long-term value creation and short-term stimulation.

If it turns out to be of major significance for the growth of a country to create ideal conditions for long-term investments by protecting risk owners against sudden, large expenses, the recent crisis has been handled incorrectly or at least suboptimally.

This also means that there is no relatively easy way for a government to get out of a crisis by means of stimulation. Consequently, it is of even greater importance to prevent crises than we used to think, to ensure that they never recur. An economic crisis is likely to have far-reaching consequences by ruining the long-term growth potential of a nation and its agents—a consequence that is unaffected and could potentially even be worsened by current short-term growth stimulation crisis countermeasures.

Bibliography

Bastiat, F. (1848). Selected Essays on Political Economy, Chapter 2, The Law. Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jensen, J.L., Sublett, S. (2017). Self-Chosen Risk and Government Intervention. In: Redefining Risk & Return. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41369-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41369-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-41368-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-41369-3

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)