Abstract

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE), though not common, is an important paediatric disorder. It has a reported incidence of 1–10 per 100,000. Some aspects of management of SUFE are controversial and evolving with advancing surgical skills and expertise. The infrequency of cases, the various classifications in use, the various surgical treatments, and lack of robust evidence for outcomes, has resulted in the lack of clear, evidence-based recommendations for treatment. The following review examined the current evidence for treating SUFE and concluded that pinning in situ is the best treatment for mild and moderate stable slip (grade B). Surgical dislocation may give better results than pinning in situ for severe stable slip (grade C). Urgent gentle reduction, capsulotomy and fixation is the best current treatment for unstable slip (grade C). Routine prophylactic pinning of the contralateral asymptomatic side is not recommended (grade C)

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- SUFE

- SCFE

- Slipped

- Stable slip

- Unstable slip

- Loders classification

- AVN

- Osteonecrosis

- FHO

- Slipped upper femoral epiphysis

Background

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE) is one of the most important paediatric and adolescent hip disorder. Incidence is 1–10:100,000. Patients usually presented with painful hip and or knee with affected leg is short and externally rotated (Fig. 6.1). The plain x-ray is usually diagnostic (Fig. 6.2). The cause is poorly understood, it is believed that increased shear forces and/or weak growth plate (the physis) in adolescence predispose to slips.

Although rare, endocrine disorders must be considered in every patient with SUFE. Loder [1] identified two types of SUFE; idiopathic type and atypical type where there is an underlying endocrine disorders or other aetiology. He studied the demographics of 433 patients with 612 SUFEs (285 idiopathic, 148 atypical) and found that weight and age were predictors for atypical SUFE and he recommended the age-weight test: the test was defined as negative when age younger than 16 years and weight ≥50th percentile and positive when beyond these boundaries. The probability of a child with a negative test result having an idiopathic SUFE was 93 %, and the probability of a child with a positive test result having an atypical SCFE was 52 %.

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis was traditionally classified as (1) pre-slip: patient has symptoms with no anatomical displacement of the femoral head, (2) acute: there is an abrupt displacement through the proximal physis with symptoms and signs developing over a short period of time (<3 weeks), (3) Chronic: present with pain in the groin, thigh, and knee of more than 3 weeks, often ranging from months to years and (4) acute on chronic: initially, patient has chronic symptoms, but develops acute symptoms as well following a sudden increase in the degree of slip [2, 3].

However, in a classic paper by Loder [4, 5] a new, clinically more relevant classification was introduced. SUFE was classified based on the patient weight-bearing status into stable when patient is able to ambulate and bear their weight and unstable when patient is unable to ambulate with or without crutches. In his series of 55 SUFEs, Loder showed that avascular necrosis (AVN) developed in 47 % of unstable slips but none of stable hips. However, unintentional reduction of the slip occurred in 26 unstable slips (out of 30) and in only 2 of the stable slips (out of 25). [4]. Several other papers confirmed Loder’s findings [6, 7–9].

Grading the severity of the slip is usually based on the radiographic findings. The Southwick angle is the most commonly used [10]. The angle is measured on the lateral view of the both hips by drawing a line perpendicular to a line connecting the posterior and anterior tips of the epiphysis at the physis. The angle between the perpendicular line and the femoral shaft line is called the lateral epiphyseal shaft angle. The Southwick angle is the difference between the lateral epiphyseal shaft angle of the slipped and the non slipped sides (Fig. 6.3). In patients with bilateral involvement, 12° is subtracted from each of the measured lateral epiphyseal angles. Mild slip (grade I) has an angle difference of less than 30°, moderate slip (grade II) has an angle difference of between 30 and 50 degrees and severe slip has a difference of over 50 degrees.

SUFE radiological grading. The Southwick angle is the difference between the lateral epiphyseal shaft angle of the slipped and the non slipped sides. Mild slip (grade I) has an angle difference of less than 30°, moderate slip (grade II) has an angle difference of between 30° and 50° and severe slip has a difference of over 50°

Treatment aim is to prevent progression of the slip without complications. Reduction of the slip to near anatomical position is desirable but this is tempered by the higher risk of AVN and chondrolysis (CL) which are surrogates for bad outcomes. The choice of treatment depends on the type of slip, its severity, and surgical expertise.

What Is the Best Treatment for a Stable Slip?

There is a consensus that the best treatment for mild and most moderate stable slip is pinning-in-situ (PIS) using a single cannulated screw (SS). This has been supported by a comprehensive review paper by Loder [11]. If the slip is severe, pinning can be technically difficult. Gentle reduction is often unsuccessful in a stable slip and forceful reduction is contraindicated as this increase the risk of AVN. The options are either PIS with re-alignment procedure later if remodeling is suboptimum or primary corrective osteotomy.

Realignment procedures can be performed at one of three levels: subcapital, femoral neck and intertrochanteric region. The ability to correct a deformity is greatest with subcapital osteotomy (where the CORA is), least with an intertrochanteric osteotomy. The risk of AVN is the highest with subcapital osteotomy and the lowest with intertrochanteric osteotomy.

We performed an extensive literature search for the best available evidence to support various treatments of stable slips. We could not find level I or II evidence. There were 16 comparative studies and several case series with a follow-up more than a year. With a few exceptions all these studies were unmatched; mild and moderate slips were treated with pinning whereas severe slips were treated with reduction (either close or open reduction) and stabilisation undermining the comparison between pinning in situ and reduction.

Tables 6.1 and 6.2 show that pinning using a single screw has the lowest rates of AVN and chondrolysis (CL) and even a better patient’s satisfaction when compared with traditional corrective osteotomies namely Dunn’s and Fish osteotomies. One point needs further emphasis that patient who had corrective osteotomies were more likely to have severe slips and their outcomes are less favourable anyway.

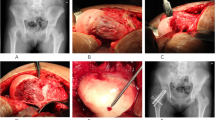

In the last two decades, the femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) has become widely recognized as an orthopaedic condition that requires treatments to prevent future osteoarthritis (OA) and premature artificial hip replacement. Ganz (Ganz et al. [54, 55] has been a pioneer in spreading the understanding of the condition and its treatment. He described a new technique of surgical dislocation of the hip involving trochanteric flip osteotomy and anterior capsulotomy preserving the blood supply to the femoral head. Although the technique has similarities to the Dunn’s osteotomy [36], hence it is also called the modified Dunn osteotomy, it poses less risk to femoral head blood supply. Six studies (81 hips) assessed the outcomes of surgical dislocation in stable slip. The crude AVN rate and CL were 3.7 % and 2.5 % respectively. Ninety percent had excellent to good results. The Harris hip score (HHS) [56] was the commonest score used in these studies and the mean was 95 points. These are promising preliminary results; however, most experts in the technique express a long learning curve and good results have not been reproduced in every centre (Alves et al. [57]).

What Is the Best Treatment for Unstable Sufe?

In his classic paper, Loder coined the term of “unstable slip”. He recognized two types of slips: unstable one where the patient has such severe pain that walking is not possible even with crutches, regardless of the duration of the symptoms and stable slips where the patient can walk with or without crutches. However, this has been misquoted and misapplied in several studies.

Treatment of unstable slip is essentially the same for stable slips; however, there are two important issues to consider:

-

1.

Being unstable, there is an opportunity for spontaneous or unintentional reduction of the severity of the slip.

-

2.

The risk for AVN is very high (50 %). It is interesting how this high risk of AVN influences surgeons’ choices differently; some adopted a minimum intervention (PIS) to prevent this risk from going up while others advocated an aggressive approach (open reduction of the slip) to reduce this high risk of AVN.

An extensive literature search revealed 23 studies that provide useful data on the outcome of unstable slips. The studies are summarised in Table 6.3. The crude AVN rates are shown in Table 6.4. The AVN rates as a surrogate for bad outcomes are comparable among various interventions with the exceptions of open reduction and internal fixation which has the lowest AVN rate of 5 %.

Eight four patients with unstable slips were treated with gentle open reduction and fixation within 24 h of the presentation. Four (5 %) only developed AVN. It is of note that this finding was heavily driven by one study (Parsch et al. [58]) of 64 patient and 3 only developed AVN. However, excluding the data of the study did not change the fact that AVN rate was significantly lower in the open reduction and internal fixation group.

The true definition of slip instability has been debated and not yet been satisfactorily defined or agreed on. Ziebarth (Ziebarth et al. [59]) found that clinical stability of SUFE as defined by Loder does not correlate with intra-operative stability. They retrospectively reviewed 82 patients with SUFE treated by open surgery and introduce the concept of “intra-operative stability” which is either intact or disrupted. They found complete physeal disruption at open surgery in 28 of the 82 hips (34 %). With classification as acute, acute-on-chronic, and chronic, the sensitivity for disrupted physes was 82 % and the specificity was 44 %. With the classification of Loder (stable and unstable) the values were 39 % and 76 %, respectively.

Kallio (Kallio et al. [60, 61]) stated that a stable slip should imply an adherent physis during weight-bearing, active leg movements, or gentle joint manipulation. Physeal instability implies that the displaced epiphysis can move in relation to the metaphysis. In a study of 55 SUFEs, he found that physeal instability is better indicated by joint effusion and inability to bear weight. A slip is very unlikely to be unstable in a child who is able to bear weight and has no sonographic effusion. This uncertainty about the definition of instability should be considered when reading the above results.

How Soon Should We Treat Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis?

This question is probably more relevant to unstable slips rather than stable because of the low AVN rate in stable slip. The timing of surgery in unstable slip remains controversial. Given the rarity of the condition, most studies that investigated the timing of surgery and outcome are underpowered to answer such a question. Lowndes et al. [8] in a meta-analysis of 5 studies (130 unstable SUFEs; 56 were treated within 24 h and 74 were treated after 24 h of symptoms onset) found that the odds for developing AVN if treatment occurs within 24 h were half if treatment occurs after 24 h. Although the difference was large, it was not statistically significant (P = 0.44) and may be a chance finding.

Peterson et al. ([62])showed early stabilisation within 24 h was associated with less AVN (3/42 = 7 %) in comparison with those stabilised after 24 h (10/49 = 20 %). Kalogrianitis et al. ([63])showed that AVN developed in 50 % (8/16) of the unstable SUFE in their series. All but one were treated between 24 and 72 h after symptom onset. They recommend immediate stabilization of unstable slips presenting within 24 h. If this is not possible, then delaying the operation until at least a week has elapsed. In contradiction, Loder [5] noted more AVN in patients treated within 48 h (7/8 versus 7/21).

Our findings supported Kalogrianitis’s findings; there were 210 patients with unstable slips who had their operation within 24 h. Twenty eight (13 %) developed AVN in comparison to (38/95) 40 % and (5/53) 9 % for those who had their operation between 24 and 72 h and those who had their operation after 72 h respectively.

Should We Treat the Contralateral Non Slipped, Asymptomatic Side?

This is also controversial. One of the main the reason for this controversy is the uncertainty about the incidence of the contralateral slip. The quoted risk of contralateral slip varies from 18 % to 60 %. Jerre (Jerre et al. [39]) reviewed 100 patients treated for SUFE to evaluate the incidence of bilateral slipping of the epiphysis at an average follow-up time of 32 years. Fifty nine patients (59 %) were judged to have had a previous bilateral SCFE; in 42 of these 59 patients (71 %), slipping of the contralateral hip was asymptomatic. In 23 patients (23 %), the diagnosis of bilateral slipping was established at primary admission, in 18 (18 %) later during adolescence, and in 18 (18 %) not until the patients were reexamined as adults and the primary radiographs were reviewed. He concluded that the incidence of bilateral slipping of the epiphysis in patients with SCFE is approximately 60 % in Sweden.

In another long term study of 155 slips by Carney (Carney et al. [13]) the slip was bilateral in 31 patients (25 %). In 14/31patients both hips were symptomatic at presentation. The rest apart from one developed within one year.

Stasikelis et al. [64] performed a retrospective review 50 children who had unilateral SUFE to determine parameters that predict the later development of a contralateral slip. They found that the modified Oxford bone age was strongly correlated with the risk of development of a contralateral slip; contralateral slip developed in 85 % of patients with a score of 16, in 11 % of patients with a score of 21, and in no patient with a score of 22 or more. The modified Oxford bone age is based on appearance and fusion of the iliac apophysis, femoral capital physis, greater and lesser trochanters. Recently, calcaneal scoring (Nicholson et al. [65]) was used to predict an elevated risk of contralateral SUFE. The obvious disadvantage is the need for a calcaneal x-ray.

A recent paper (Phillips et al. [66]) examined the posterior slope angle (PSA) in 132 patients as a predictive for developing a contralateral slip. The mean was 17.2° ± 5.6° in 42 patients who had subsequently developed a contralateral slip, which was significantly higher (P = 0.001) than that of 10.8° ± 4.2° for the 90 patients who had had a unilateral slip. If a posterior sloping angle of 14° were used as an indication for prophylactic fixation, 35 (of 42 = 83.3 %) would have been prevented, and 19 ( of 90 = 21.1 %) would have been pinned unnecessarily (Fig. 6.4).

Posterior slope angle. The posterior sloping angle (PSA) measured by a line (A) from the center of the femoral shaft through the center of the metaphysis. A second line (B) is drawn from one edge of the physis to the other, which represents the angle of the physis. Where lines A and B intersect, a line (C) is drawn perpendicular to line A. The PSA is the angle formed by lines B and C posteriorly as illustrated

Prophylactic pinning is not devoid of risk and it should be weighed against the benefit. The proponents and opponents have some evidence to support their views (Jerre et al. [67]; Sankar et al. [68]; Clement et al. [69]). Most studies showed that the average risk of contralateral lateral slip is around 18 % (Larson et al. [70]; Baghdadi et al. [71]). Most were mild slips and when treated they rarely went to develop AVN. Risk of prophylactic pinning is in the region of 5 % including AVN and peri-prosthetic fractures (Sankar et al. [68]; Baghdadi et al. [71]; Kroin et al. [72]).

We recommend a pragmatic approach for contralateral pinning where the following factors play a role in decision making:

-

1.

Age of the child (<10 years is associated with a higher risk of bilaterality).

-

2.

Slips associated with renal osteodystrophy and endocrine disorders (a high incidence of bilaterality)

-

3.

Poor compliance of the child and family.

-

4.

The nature of current slip (very bad slip occurred over a very short period of time may justify pinning the other side)

What Are the Natural History and Long Term Outcomes of Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis?

Natural history is the usual course of development of a disease or condition, especially in the absence of treatment. This is difficult to establish in SUFE simply because most published series reported patients who were treated. There were a few cross sectional studies that reported on the outcomes of what were presumed as untreated slips. Even if these were true slips, they were probably mild stable slips that would pursue a different natural course from most other slips. Most studies used AVN as a surrogate for bad outcome. Although AVN is rare in stable slips, bad outcome is not uncommon in severe stable slips. Larson et al. [73] reviewed 33,000 hip replacement performed in their centre between 1954 and 2007 and found SUFE was the indication in 38 hips (in 33 patients). The main reasons for hip replacement in this subset were AVN or chondrolysis in 25 hips and degenerative changes and/or impingement in 13 hips. All slips underwent either pin fixation (27) or primary osteotomy (9). Mean time from slip to hip replacement was 7.4 years in patients with AVN or chondrolysis and 23.6 years in patients with degenerative change (P < 0.0002). Mean age at arthroplasty was 20 years in the AVN or chondrolysis group and 38 years in the degenerative group (P < 0.0001). Sixteen hips (42 %) required revision arthroplasty at a mean of 11.6 years postoperatively, most commonly for component loosening and/or polyethylene wear. Kaplan Meier 5-year survival free from revision for all causes was 87 % overall and 95 % in the total hip arthroplasty subset.

Carney [74] published a series of 31 untreated chronic SUFE with a long term follow-up (ranged from 26 to 54 years). Authors stated the reasons for no treatments were not always clear from the medical records but included family refusal, delayed presentation or treating the more serious side. There were 17 mild, 11 moderate and 3 severe. The mean IHS was 89 points (92 points in mild slips, 87 points in moderate slips and 75 points in severe slips). All severe and moderate slips showed radiographic features of OA in contrast to 13 % of those with mild slip. Complications were occurred in 4 slips (1 AVN and 2 further displacements developed 3 severe slips and 1 chondrolysis in 1 mild slip.

In another series, Carney (Carney et al. [13]) reported on 155 SUFEs in 124 patients after 41 year follow up. Forty-two percent of the slips were mild; 32 % were moderate; and 26 % were severe. Various treatments methods were used (see Table 6.4). They found that there is mild deterioration that is related to the severity of the slip and complications of treatment (Fig. 6.5). Realignment was associated with a risk of substantial complications and adversely affects the natural course of the disease (Fig. 6.6).

Long-term follow-up of treated slipped upper femoral epiphysis (Adapted from Carney (Carney et al. [13]))

Long-term follow-up of treated slipped upper femoral epiphysis (Adapted from Carney (Carney et al. [13]))

A summary of recommendations is given in Table 6.5.

References

Loder RT, Greenfield ML. Clinical characteristics of children with atypical and idiopathic slipped capital femoral epiphysis: description of the age-weight test and implications for further diagnostic investigation. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):481–7.

Alshryda S, Jones S, et al. Postgraduate paediatric orthopaedics: the candidate’s guide to the FRCS (Tr and Orth) examination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

Fahey JJ, O'Brien ET. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: review of the literature and report of ten cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:1105–27.

Alshryda, S. and J. Wright (2014). Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: the importance of physeal stability. Classic Papers in Orthopaedics. London: Springer. 2014; 547–8.

Loder RT, Richards BS, et al. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: the importance of physeal stability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(8):1134–40.

Lim YJ, Lam KS, et al. Review of the management outcome of slipped capital femoral epiphysis and the role of prophylactic contra-lateral pinning re-examined. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(3):184–7.

Alshryda S, Tsang K, et al. Severe slipped upper femoral epiphysis; fish osteotomy versus pinning-in-situ: an eleven year perspective. Surgeon. 2013;12(5):244–8.

Lowndes S, K. A, Emery D, Sim J, Maffulli N. Management of unstable slipped upper femoral epiphysis: a meta-analysis. Br Med Bull. 2009;90:133–46.

Alshryda S, Tsang K, Al-Shryda J, Blenkinsopp J, Adedapo A, Montgomery R, et al. Interventions for treating slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013; Issue 2. Art. No.: CD010397. DOI: 101002/14651858CD010397.

Southwick WO. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(8):1151–2.

Loder RT, Dietz FR. What is the best evidence for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis? J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(Suppl 2):S158–65.

Betz RR. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a spina cast. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(3):489–90.

Carney BT, Weinstein SL, et al. Long-term follow-up of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(5):667–74.

Meier MC, Meyer LC, et al. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a spica cast. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(10):1522–9.

Adamczyk MJ, Weiner DS, et al. A 50-year experience with bone graft epiphysiodesis in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):578–83.

Rao SB, Crawford AH, et al. Open bone peg epiphysiodesis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(1):37–48.

Schmidt TL, Cimino WG, et al. Allograft epiphysiodesis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:61–76.

Szypryt EP, Clement DA, et al. Open reduction or epiphysiodesis for slipped upper femoral epiphysis. A comparison of Dunn’s operation and the Heyman-Herndon procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(5):737–42.

Zahrawi FB, Stephens TL, et al. Comparative study of pinning in situ and open epiphysiodesis in 105 patients with slipped capital femoral epiphyses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:160–8.

Aronson DD, Loder RT. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in black children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12(1):74–9.

Aronson DD, Carlson WE. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A prospective study of fixation with a single screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(6):810–9.

Blanco JS, Taylor B, et al. Comparison of single pin versus multiple pin fixation in treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12(3):384–9.

Gonzalez-Moran G, Carsi B, et al. Results after preoperative traction and pinning in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: K wires versus cannulated screws. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7(1):53–8.

Herman MJ, Dormans JP, et al. Screw fixation of Grade III slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:77–85.

Kenny P, H. T, Sedhom M, Dowling F, Moore DP, Fogarty EE. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis. a retrospective, clinical and radiological study of fixation with a single screw. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12(2):97–9.

Koval KJ, L. WB, Rose D, Koval RP, Grant A, Strongwater A. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a cannulated-screw technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(9):1370–7.

Lim YJ, Lam KS, et al. Management outcome and the role of manipulation in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2007;15(3):334–8.

Novais EN, Hill MK, et al. Modified Dunn procedure is superior to in Situ pinning for short-term clinical and radiographic improvement in severe stable SCFE. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;473(6):2108–17.

Souder CD, Bomar JD, et al. The role of capital realignment versus in situ stabilization for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(8):791–8.

Ward WT, Stefko J, et al. Fixation with a single screw for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(6):799–809.

Dreghorn CR, Knight D, et al. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis–a review of 12 years of experience in Glasgow (1972–1983). J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7(3):283–7.

Barros JW, Tukiama. G, Fontoura C, Barsam NH, Pereira ES. Trapezoid osteotomy for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Int Orthop. 2000;24(2):83–7.

Broughton NS, Todd RC, et al. Open reduction of the severely slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(3):435–9.

DeRosa GP, Mullins RC, et al. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:48–60.

Diab M, Hresko MT, et al. Intertrochanteric versus subcapital osteotomy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:204–12.

Dunn DM, Angel JC. Replacement of the femoral head by open operation in severe adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60-B(3):394–403.

Fish JB. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A follow-up note. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(1):46–59.

Fron D, Forgues D, et al. Follow-up study of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated with Dunn's osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(3):320–5.

Jerre R, Billing L, et al. Bilaterality in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: importance of a reliable radiographic method. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5(2):80–4.

Nishiyama K, Sakamaki. T, Ishii Y. Follow-up study of the subcapital wedge osteotomy for severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9(4):412–6.

Velasco R, Schai PA, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a long-term follow-up study after open reduction of the femoral head combined with subcapital wedge resection. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7(1):43–52.

Madan SS, Cooper AP, et al. The treatment of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis via the Ganz surgical dislocation and anatomical reduction: a prospective study. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(3):424–9.

Masse A, Aprato A, et al. Surgical hip dislocation for anatomic reorientation of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: preliminary results. Hip Int. 2012;22(2):137–44.

Ziebarth K, Zilkens C, et al. Capital realignment for moderate and severe SCFE using a modified Dunn procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):704–16.

Abraham E, Garst J, et al. Treatment of moderate to severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis with extracapsular base-of-neck osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13(3):294–302.

Kramer WG, Craig WA, et al. Compensating osteotomy at the base of the femoral neck for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(6):796–800.

Ireland J, Newman PH. Triplane osteotomy for severely slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60-B(3):390–3.

Kartenbender K, Cordier W, et al. Long-term follow-up study after corrective Imhauser osteotomy for severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(6):749–56.

Parsch K, Zehender H, et al. Intertrochanteric corrective osteotomy for moderate and severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8(3):223–30.

Rao JP, Francis AM, et al. The treatment of chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis by biplane osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(8):1169–75.

Salvati EA, Robinson Jr JH, et al. Southwick osteotomy for severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis: results and complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(4):561–70.

Schai PA, Exner GU, et al. Prevention of secondary coxarthrosis in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a long-term follow-up study after corrective intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5(3):135–43.

Southwick WO. Osteotomy through the lesser trochanter for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49(5):807–35.

Ganz R, Gill TJ, et al. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1119–24.

Ganz R, Parvizi. J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:112–20.

Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(4):737–55.

Alves C, Steele M, et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis by means of surgical dislocation does not decrease the rate of avascular necrosis: a preliminary study. J Child Orthop. 2013;6(4):277–83.

Parsch K, Weller S, et al. Open reduction and smooth Kirschner wire fixation for unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(1):1–8.

Ziebarth K, Domayer S, et al. Clinical stability of slipped capital femoral epiphysis does not correlate with intraoperative stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2274–9.

Kallio PE, Paterson DC, et al. Classification in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Sonographic assessment of stability and remodeling. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;294:196–203.

Kallio PE, Mah ET, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Incidence and clinical assessment of physeal instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(5):752–5.

Peterson MD, Weiner DS, et al. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: the value and safety of urgent manipulative reduction. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17(5):648–54.

Kalogrianitis S, Tan CK, et al. Does unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis require urgent stabilization? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16(1):6–9.

Stasikelis PJ, Sullivan CM, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Prediction of contralateral involvement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(8):1149–55.

Nicholson AD, Huez CM, Sanders JO, Liu RW, Cooperman DR. Calcaneal Scoring as an Adjunct to Modified Oxford Hip Scores: Prediction of Contralateral Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36(2):132–8.

Phillips PM, Phadnis J, et al. Posterior sloping angle as a predictor of contralateral slip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(2):146–50.

Jerre R, Billing L, et al. The contralateral hip in patients primarily treated for unilateral slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Long-term follow-up of 61 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(4):563–7.

Sankar WN, Novais EN, et al. What are the risks of prophylactic pinning to prevent contralateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;471(7):2118–23.

Clement ND, Vats A, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: is it worth the risk and cost not to offer prophylactic fixation of the contralateral hip? Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(10):1428–34.

Larson AN, Yu EM, et al. Incidence of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a population-based study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2009;19(1):9–12.

Baghdadi YM, Larson AN, et al. The fate of hips that are not prophylactically pinned after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(7):2124–31.

Kroin E, Frank JM, et al. Two cases of avascular necrosis after prophylactic pinning of the asymptomatic, contralateral femoral head for slipped capital femoral epiphysis: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015;35(4):363–6.

Larson AN, McIntosh AL, et al. Avascular necrosis most common indication for hip arthroplasty in patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(8):767–73.

Carney BT, Weinstein SL. Natural history of untreated chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:43–7.

Aronson J, Tursky EA. The torsional basis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;322:37–42.

Biring GS, Hashemi-Nejad A, et al. Outcomes of subcapital cuneiform osteotomy for the treatment of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis after skeletal maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(10):1379–84.

Chen RC, Schoenecker PL, et al. Urgent reduction, fixation, and arthrotomy for unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(7):687–94.

Fallath S, Letts M. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an analysis of treatment outcome according to physeal stability. Can J Surg. 2004;47(4):284–9.

Gordon JE, Abrahams MS, et al. Early reduction, arthrotomy, and cannulated screw fixation in unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(3):352–8.

Kennedy JG, Hresko MT, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head associated with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(2):189–93.

Palocaren T, Holmes L, et al. Outcome of in situ pinning in patients with unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis: assessment of risk factors associated with avascular necrosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;30(1):31–6.

Phillips SA, Griffiths WE, et al. The timing of reduction and stabilisation of the acute, unstable, slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1046–9.

Rhoad RC, Davidson RS, et al. Pretreatment bone scan in SCFE: a predictor of ischemia and avascular necrosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19(2):164–8.

Sankar WN, McPartland TG, et al. The unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis: risk factors for osteonecrosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(6):544–8.

Sankar WN, Vanderhave KL, et al. The modified Dunn procedure for unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a multicenter perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(7):585–91.

Seller K, Wild A, et al. Clinical outcome after transfixation of the epiphysis with Kirschner wires in unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Int Orthop. 2006;30(5):342–7.

Tokmakova KP, Stanton RP, et al. Factors influencing the development of osteonecrosis in patients treated for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(5):798–801.

Carlioz HV, Vogt JC, Barba L, Doursounian L. Treatment of slipped upper femoral epiphysis: 80 cases operated on over 10 years (1968-1978). J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4(2):153–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alshryda, S., Tsang, K., De Kiewiet, G. (2017). Evidence-Based Treatment for Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis. In: Alshryda, S., Huntley, J., Banaszkiewicz, P. (eds) Paediatric Orthopaedics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41142-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41142-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-41140-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-41142-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)