Abstract

The work environment in multinational corporations (MNCs) is specific and demanding including intercultural interactions with co-workers and clients and using a foreign language. Some individual resources can help in dealing with these circumstances. Individual resources refer to personal dispositions, competencies and prior experiences. With regard to previous studies, a caravan of personal resources, namely Psychological Capital (Luthans et al., Pers Psychol 60(3): 541–572, 2007), can reveal the source of inconsistencies in results in a multicultural work setting.

The aim of this study was to examine the relationships between positive psychological capital and other individual and professional resources (functional language, prior international experiences, age, and job tenure), which can help employees to deal with a demanding multinational work environment and particularly with intercultural interactions.

The results of a quantitative study among a Polish group of employees in MNCs have demonstrated that psychological capital was slightly correlated with their international experience and moderately correlated with proficiency in a foreign language used in the corporation as a functional language. The psychological capital of the respondents was not correlated with age, but was slightly correlated with their job tenure. The differences between the two subgroups depended on the job position, indicating that the supervisors had a higher level of psychological capital than employees (large effect size) as well as having a higher level of resilience, hope and optimism (moderate effect sizes).

Including some shortcomings of the study, the association between positive psychological capital and other individual resources was discussed and some practical implications were also indicated. The research suggests that organizations can reap benefits from the individual resources of employees and can play an active role in the development of psychological capital. Thus, they may create their competitive advantage on the labour market.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The work environment in multinational corporations (MNCs) is specific and demanding (Stahl et al. 2010). It includes requirements such as intercultural interactions with co-workers and clients and using a foreign language (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015a, b). Some individual resources can help in dealing with these circumstances. Individual resources refer to personal dispositions, skills, competencies and prior experiences. The individual resources of employees are important for an organization because they create organizational social capital (Donaldson and Ko 2010). Individual resources such as prior experience in a multicultural environment, both in private and professional life, as well as personal dispositions such as psychological capital may result in better functioning of employees and contribute to the success of organization. Psychological capital consists of resilience, optimism, self-efficacy and hope (Luthans et al. 2007). It may help to explain the quality of intercultural interactions in a multicultural workplace.

The aim of this study was to examine relationships between positive psychological capital and other individual and professional resources (functional language, prior international experiences, age and job tenure), which can help employees to deal with a demanding multinational work environment and particularly with intercultural interactions.

The chapter presents a theoretical conceptualization of positive psychological capital and its associations with other individual resources important in a multinational work setting as well as for the functioning of employees and organizational outcomes. Further, the results of a quantitative study among a Polish study sample are shown. The association between positive psychological capital and other individual resources is discussed and some practical implications are indicated.

2 Study Background

2.1 Positive Psychological Capital and Its Components

Psychological capital (PsyCap) is an individual positive psychological state which is characterized by possession of self-confidence and belief in one’s own ability to cope with difficult tasks (self-efficacy); making positive attributions about current success and also in the future (optimism); focusing on goals and perseverance in the pursuit of them, and if necessary, redefining the ways of reaching these goals (hope); being flexible in the face of challenges and obstacles in order to achieve success (resilience) (Luthans et al. 2007). The four personal resources that constitute psychological capital are like a caravan, which follow and support each other. It is the specific profile or constellation of personal resources whereby the employee can improve their functioning in the workplace. Psychological capital is also dynamic and a developmental state which can be shaped and built by the organizational activities (Peterson et al. 2011). This means that psychological capital may change over time as a result of new experiences and new interactions in professional circumstances. Thus psychological capital has a rewarding value because personal resource can be invested and will create benefits in the future (Hobfoll 2011; Łaguna 2015).

The components of psychological capital, efficacy, resilience, hope and optimism, are interrelated. Even more important, their cooperation leads to the effect of synergy. Therefore, they are more impactful as a set of personal resources than as separate resources. In other words, a caravan of personal resources presented by the profile of their relationship can contribute to other and larger consequences compared to a single resource. These outcomes are mainly positive attitudes towards work (Donaldson and Ko 2010; Tims et al. 2012).

Self-efficacy as a component of PsyCap is defined as an individual’s belief in terms of his/her abilities to mobilize motivation and cognitive resources to take the action necessary for goal achievement (Luthans et al. 2007). Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in his/her competencies more than currently possessed skills, which helps him/her to achieve professional success. This is closely related to job performance, but does not refer to specific tasks, but rather just the confidence in his/her own skills and knowledge. Employees with higher efficacy are more likely to see job demands as a challenge than a hindrance because their personal efforts are useful and necessary. The way in which individuals evaluate demands shows that they perceive more positive than negative attributes and finally they predict success in face of adversity (Lazarus 1991).

Resilience, the next component of psychological capital, is characterized by a positive psychological capacity to cope with uncertainty and conflict at work. Thus, resilience is useful in a demanding or stressful environment. It allows recovery of balance after a struggle with adverse and ambiguous conditions. Resilience promotes an attitude of responsibility and openness to change. A higher level of resilience is strongly related to positive emotions, happiness and job satisfaction (Fredrickson 2001; Luthans et al. 2007).

Optimism is the next personal resource, which is related to expectations of positive outcomes and positive events in the future. It is directly associated with positive job-related emotions, e.g. pride, happiness, or enthusiasm. Thus, individuals with higher optimism can more easily evaluate what should be done and what should be abandoned and can be more realistic. Thus, optimism is a positive affective and motivational state focused on expectation of positive results and striving for success (Luthans et al. 2007).

Hope is also a positive motivational state focused on the achievement of success. It is described by three characteristics: being agentic (entrepreneurial and proactive), planning, and being goal-oriented. This means that hope involves energy to reach desired goals and to choose alternative paths to achieve these goals (Snyder 2002). Further, hope is an ability to clarify how success can be pursued. Therefore, in terms of personal resources, hope increases the engagement and motivation as well as the vitality of employees.

2.2 Psychological Capital an Its Association with Individual and Organizational Outcomes

Psychological capital as a caravan of personal resources is associated with the functioning of employees and with social capital in organizations (Luthans et al. 2007; Walumbwa et al. 2011). Individual functioning is represented by psychological well-being in the work context, including job-related affective well-being (balance between pleasant and unpleasant feelings during work) and job satisfaction (cognitive evaluations of different aspects of work) (Diener 2012; Fisher 2014). Psychological well-being also includes more complex positive states such as thriving (linking vitality and learning) (Spreitzer et al. 2005) and negative states such as burnout (being exhausted and withdrawal) (Maslach et al. 2001). Further, an organization can receive benefits from the PsyCap of their employees in their mastery of job performance, improved leadership, reduced cost of work (e.g. absenteeism and intention to leave the job) and promoted creativity and innovation (Avey et al. 2010a, b; Rego et al. 2012).

PsyCap can improve individual job-related functioning. It is associated with higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment mainly due to efficacy, optimism and hope (Avey et al. 2011; Luthans et al. 2007; Larson and Luthans 2006). PsyCap emphasizes pleasant emotions experience during work (Avey et al. 2010a, b, 2011). It is also an important resource in dealing with job stress and stress outcomes (e.g. job burnout). In particularly, efficacy and resilience help in overcoming difficulties, as well as minimalizing the symptoms experienced during stress. Consequently, PsyCap reduces negative organizational outcomes such as the intention to leave the job (Avey et al. 2009, 2010a, b). Findings of some recent studies have revealed that PsyCap is associated with work engagement (Luthans 2012; Vink et al. 2011; Paek et al. 2015). Moreover, PsyCap strengthens and facilitates thriving in such way that self-efficacy and resilience enhance learning, while hope and optimism promote vitality (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015b).

Organizations may support the PsyCap of their employees because it is related with organizational resources (Paterson et al. 2014; Vink et al. 2011). Employees who have a rich PsyCap aim for growth and development, and they focus more on mastery in job performance (Avey et al. 2011; Luthans et al. 2008). Moreover, authentic leadership fosters the psychological capital of employees and further leads to creation of value added in the organization (Avey et al. 2010a, b; Rego et al. 2012; Walumbwa et al. 2011).

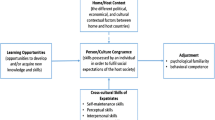

2.3 Individual Resources in Intercultural Interactions

Dealing with intercultural interactions in a work environment can be supported by individual skills (e.g. language), prior international experience (in private or professional life) and other socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. age, job tenure, job position). These individual resources may be related to the PsyCap of employees.

International experiences refer to the variety of experiences (in different time and frequency) that a person gained while working, living, studying or traveling abroad (Takeuchi and Chen 2013). International experience is a prominent factor related to adjustment. In the meta-analysis of studies on expatriates’ work-related outcomes, Hechanova et al. (2003) have indicated that interactional adjustment, which is defined as comfortable socialization and interactions with locals, appears to be of particular importance. Moreover, the amount of interactions with host locals was positively related to work adjustment. Additionally, permanent contact and interactions with another culture can induce the individuals of one culture to change their values, attitudes, and behavior (Darawong and Igel 2012) The findings revealed that close and regular contacts in multicultural job teams positively affect job satisfaction, feelings about one’s job and also create positive attitudes toward expatriates. It is possible that having international experience in private and professional life can help individuals broaden their PsyCap. Additionally, this relation between PsyCap and adjustment in a multicultural environment can be reciprocal. This means that broadened PsyCap facilitates individual adjustment in professional life through being open, tolerant, and curious about other cultures (Rozkwitalska and Basinska 2015b). Based on previous studies the proposition is formulated that:

-

Proposition 1: Psychological capital is positively correlated with international experience.

The linguistic diversity of multicultural organizations, common language and communication frequency are more demanding conditions in multinational work settings. These demands affect interactions with others (supervisors, co-workers and clients) and job satisfaction. In the study conducted by Lauring and Selmer (2011) frequent communication contributed to satisfaction, while the necessity of using a common language might decrease it. Thus fluency and proficiency in business language can facilitate both professional and social interactions as well as job performance. Accordingly, the following proposition is formulated:

-

Proposition 2: Psychological capital is positively correlated with satisfaction with proficiency in a functional language.

Some socio-demographics of employees and their job-related characteristics can affect intercultural interactions. Previous studies have shown that PsyCap is not usually associated with age and education (socio-demographic variables) or with job tenure and job positions (organizational variables) (Avey et al. 2010a, b; Luthans et al. 2007). Thus, PsyCap does not depend solely on the efforts of individuals, but can be promoted by organizations through their resources. Thus following propositions are expected:

-

Proposition 3: Psychological capital is not correlated with age and work tenure.

-

Proposition 4: Psychological capital is not dependent on job position it means that supervisors and other personnel do not different in their level of psychological capital.

3 Psychological Capital in Multicultural Work Settings: The Polish Example

3.1 Methodology

The aim of this study was to examine the relation between psychological capital as a caravan and prior international experience, satisfaction with proficiency in functional language and age (personal variables) as well as job tenure and job position (organizational variables).

The sample consisted of 137 individuals who work as managers and specialists in Polish subsidiaries of MNCs. They are involved in intercultural interactions, both face-to-face and virtual, in a daily routine. In this group, there were 70 women (51 %) and 59 (43 %) individuals held a managerial position. A quantitative study based on subjective evaluation was conducted. Correlational design was applied.

Psychological Capital was measured using a shortened version of PsyCap (TA-412-PCQ Self Form-Polish Luthans et al. 2007, licensed by Rozkwitalska). This 12-item questionnaire assesses the four psychological resources such as efficacy (3 items), resilience (3 items), hope (4 items) and optimism (2 items). The five-point Likert scale was applied (range from 1 never to 5 always). Theindex of PsyCap is calculated by summarizing scores divided by the item. Higher scores indicate a higher level of PsyCap. In this study, the reliability coefficient was good (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.87).

The satisfaction with proficiency in a functional language was evaluated using one question: “Overall, my command of a foreign language (the official language in my company) is proficient”. The six-point scale was used from 1 strongly disagree to 6 strongly agree.

International experience was evaluated as an index of different kinds of experiences. There are the following seven items: working in a multinational corporation in the past, working abroad, living abroad, studying abroad, private and business travel abroad as well as having a close family member of another nationality. Respondents evaluated their experiences on the bimodal scale (no = 0 yes = 1). Higher scores (maximum 7) indicate higher prior international experience in private and working life. In this study, the reliability coefficient was good (r—tetrachoric coefficient = 0.75).

To analyze the data, the following statistical methods were chosen. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between psychological capital and other study variables. A student’s t-test for independent samples was applied to calculate the differences between two subgroups (supervisors and employees). Additionally, Cohen’s-d effect size was calculated. The rule of thumb is that Cohen’s-d and a correlation coefficient higher than 0.50 are viewed as a large, between 0.30 and 0.50 as moderate, and less than 0.30 as a small effect size (Cohen 1988).

3.2 Results

The majority of the respondents (93 %) had worked in MNCs in the past and had worked abroad (60 %). Above half of them had lived abroad (55 %). Additionally, one fourth of the research group had studied in a foreign country. They were often traveling to other countries for private (91 %) as well as business reasons (69 %). Twenty-four respondents (18 %) have a close family member of another nationality. They are proficient in the language, which is used as the functional language (M = 4.92 SD = 0.98).

The psychological capital of the employees in MNCs was relatively high. The values ranged from 3 to 6 points. The average value (M = 4.63 SD = 0.62) was related to the 75th percentile of the absolute value of scale.

The profile of a caravan of resources indicated that the salient resource of PsyCap is efficacy (M = 4.84 SD = 0.84), followed by resilience (M = 4.65 SD = 0.73) and hope (M = 4.61 SD = 0.75), and lastly optimism (M = 4.44 SD = 0.81). This profile described the research group as having high efficacy, supplemented by resilience and hope with a smaller dose of optimism.

Firstly, the correlation between PsyCap and international experience was tested. The psychological capital of the employees in MNCs was slightly correlated with their international experience (r = 0.22 p = 0.012). This means that a higher PsyCap is interrelated with international experience in the past. Interestingly, business trips were the most prominent component of international experience. None of the four resources separately was correlated with international experience of the respondents. Proposition 1 was supported (small effect size). The results may suggest that PsyCap can be mainly broadened in the work context.

Further, the correlation between PsyCap and satisfaction with proficiency in a foreign language was verified. The psychological capital of the employees in MNCs was moderately correlated with satisfaction with their proficiency in a foreign language, which is used in the corporation as a functional language (r = 0.34 p < 0.001). None of the four resources evaluated separately was correlated with subjective satisfaction with proficiency in a foreign language. Proposition 2 was supported (moderate effect size). This means that higher PsyCap accompanied proficiency in a functional language.

Next, the correlations between PsyCap and socio-demographic variables such as age and job tenure were assessed. The psychological capital of the employees in MNCs was not correlated with their age (r = 0.01 p = 0.970). Additionally, none of the four resources was correlated with age. In contrast, the PsyCap of respondents was slightly correlated with their job tenure (r = 0.21 p = 0.018). Efficacy, resilience and optimism were not correlated with job tenure. However, the results indicate that hope was slightly correlated with these types of socio-demographic variables (r = 0.21 p = 0.014). Proposition 3 was partly supported (small effect size for the relationship between PsyCap and job tenure). This means that higher PsyCap followed higher job experience but not age.

Finally, PsyCap dependent on job position was examined. The results are presented in details in Table 1.

The differences between the two subgroups dependent on job position demonstrated that the respondents who hold positions as supervisors are characterized by a higher level of PsyCap than employees (large effect size), and they had a higher level of resilience, hope and optimism (moderate effect sizes). Thus, proposition 4 was not supported, because the level of PsyCap was different between the employees and the supervisors in MNCs. The supervisors compared to the executive personnel had a broader PsyCap and its components, excluding efficacy.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

The results of the study presented here demonstrated that the PsyCap of the group of employees in MNCs was slightly correlated with their international experience and moderately correlated with proficiency in a foreign language which is used in MNCs as a functional language. The psychological capital of the respondents was not correlated with age, but it was slightly correlated with their job tenure. The differences between the two subgroups dependent on job position indicated that the supervisors had a higher level of PsyCap than employees (large effect size) and had higher level of resilience, hope and optimism (moderate effect sizes) as well.

The findings presented indicate that greater prior international experience is interrelated with broadened PsyCap, which can facilitate psychological and professional functioning in MNCs. It is interesting that professional experience related with business trips was the most prominent among different kinds of experiences. This may suggest that prior professional experience may have more significant meaning. This finding is somewhat consistent with previous studies focused on expatriates that described a small effect between international experience acquired in the past and work and interaction adjustment, but not with general adjustment (Hechanova et al. 2003; Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. 2005). In contrast, some researchers have suggested that the effect between prior international experience and psychological adjustment is non-linear (Takeuchi and Chen 2013). Thus, future studies may evaluate the stage of international experience and its impact on functioning at work.

Next, PsyCap was broadened due to proficiency in a foreign language, which is used as a functional language. Fluency and proficiency in communication in different languages facilitate intercultural interactions in both professional and privatelife. This experience is built on the fluency and time duration in which a foreign language was used and trained (Lauring and Selmer 2011; Takeuchi and Chen 2013). This finding can have the practical implication that organizations can support employees in the development of this competence through the arrangement of professional courses and integration events. Eventually, it may result in broadened PsyCap of employees and further strengthen the social capital of an organization.

In congruence with expectations (Avey et al. 2010a, b; Luthans et al. 2007), the PsyCap of employees was not correlated with age. Yet, in contrast to expectations, PsyCap was slightly correlated with their job tenure. Thus, greater job experience was interrelated with a richer PsyCap of the respondents. This may suggest that professional and organizational factors may have a prominent importance.

Following the final result, the level of PsyCap was dependent on job position. In the research group, the supervisors had higher level of PsyCap than the employees. This may indicate that individuals with broadened PsyCap can be more successful in the organization. From the practical point of view, leaders with excellent PsyCap can help employees to grow and develop. These leaders can also stimulate learning and collaboration among co-workers (Rego et al. 2012). Additionally, the supervisors had a higher level of resilience, hope and optimism, but the size of this effect was smaller than the effect for PsyCap. This may indicate that a caravan of resources creates a stronger effect than the effects of a separate resource (Luthans et al. 2007).

Being aware of some shortcomings of the presented study, some practical implications can be outlined. Psychological capital as a caravan of personal resources associates with employees functioning and it stimulates social capital in organizations (Luthans et al. 2007; Walumbwa et al. 2011). Thus, it implies individual and organizational benefits. Organizations can reap benefits from the individual resources of employees, and can play an active role in development of PsyCap as well (Paterson et al. 2014; Vink et al. 2011). Organizations and their supervisors can also create opportunities to strengthen the psychological capital of employees by introducing interventions and systematic training (Luthans et al. 2006, 2008). Organizations can gain from the PsyCap of their employees and can create their competitive advantage in the labor market (Avey et al. 2010a, b; Donaldson and Ko 2010; Rego et al. 2012).

References

Avey JB, Luthans F, Jensen SM (2009) Psychological capital: a positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum Resour Manage 48(5):677–693

Avey JB, Luthans F, Youssef CM (2010a) The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. J Manage 36(2):430–452

Avey JB, Luthans F, Smith RM, Palmer NF (2010b) Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J Occup Health Psychol 15(1):17–28

Avey JB, Reichard RJ, Luthans F, Mhatre KH (2011) Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum Resour Dev Q 22(2):127–152

Bhaskar-Shrinivas P, Harrison DA, Shaffer MA, Luk DM (2005) Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Acad Manage J 48:277–294

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for behavioral science. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Darawong C, Igel B (2012) Acculturation of local new product development team members in MNC subsidiaries in Thailand. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 24(3):351–371

Diener E (2012) New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. Am Psychol 67(8):590–597

Donaldson SI, Ko I (2010) Positive organizational psychology, behavior, and scholarship: a review of the emerging literature and evidence base. J Posit Psychol 5(3):177–191

Fisher CD (2014) Conceptualizing and measuring wellbeing at work. Wellbeing 3:1:2, pp 1–25. doi:10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell018

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 56(3):218–226

Hechanova R, Beehr TA, Christiansen ND (2003) Antecedents and consequences of employees’ adjustment to overseas assignment: a meta-analytic review. Appl Psychol 52(2):213–236

Hobfoll SE (2011) Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J Occup Organ Psychol 84(1):116–122

Łaguna M (2015) Zasoby osobiste jako potencjał w realizacji celów. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne 20(1):5–15

Larson M, Luthans F (2006) Potential added value of psychological capital in predicting work attitudes. J Leadersh Org Stud 13(2):75–92

Lauring J, Selmer J (2011) Multicultural organizations: common language, knowledge sharing and performance. Pers Rev 40(3):324–343

Lazarus RS (1991) Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am Psychol 46(4):352–367

Luthans F (2012) Psychological capital: implications for HRD, retrospective analysis, and future directions. Hum Resour Dev Q 23:1–8

Luthans F, Avey JB, Avolio BJ, Norman SM, Combs GM (2006) Psychological capital development: toward a micro‐intervention. J Organ Behav 27(3):387–393

Luthans F, Avolio BJ, Avey JB, Norman SM (2007) Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers Psychol 60(3):541–572

Luthans F, Avey JB, Patera JL (2008) Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Acad Manage Learn Educ 7(2):209–221

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):397–422

Paek S, Schuckert M, Kim TT, Lee G (2015) Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. Int J Hosp Manage 50:9–26

Paterson TA, Luthans F, Jeung W (2014) Thriving at work: impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J Organ Behav 35(3):434–446

Peterson SJ, Luthans F, Avolio BJ, Walumbwa FO, Zhang Z (2011) Psychological capital and employee performance: a latent growth modeling approach. Pers Psychol 64(2):427–450

Rego A, Sousa F, Marques C, Cunha MP (2012) Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. J Bus Res 65(3):429–437

Rozkwitalska M, Basinska BA (2015a) Job satisfaction in the multicultural environment of multinational corporations–using the positive approach to empower organizational success. Balt J Manage 10(3):366–387

Rozkwitalska M, Basinska BA (2015b) Thriving in multicultural work settings. In: Vrontis D, Weber Y, Tsoukatos E (eds) 8th Annual Conference of EuroMed Academy of Business. Innovation, entrepreneurship and sustainable value chain in dynamic environment. Conference Book Proceeding. EuroMed Press, Verona, Italy, pp. 1708–1721

Snyder CR (2002) Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol Inq 13(4):249–275

Spreitzer G, Sutcliffe K, Dutton J, Sonenshein S, Grant AM (2005) A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ Sci 16(5):537–549

Stahl GK, Maznevski ML, Voigt A, Jonsen K (2010) Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: a meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. J Int Bus Stud 41(4):690–709

Takeuchi R, Chen J (2013) The impact of international experiences for expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment: a theoretical review and a critique. Organ Psychol Rev 3(3):248–290

Tims M, Bakker AB, Derks D (2012) Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J Vocat Behav 80(1):173–186

Vink J, Ouweneel E, Le Blanc P (2011) Psychological resources for engaged employees: psychological capital in the job demands-resources model [Psychologische energiebronnen voor bevlogen werknemers: Psychologisch kapitaal in her Job Demands-Resources model]. Gedrag en Organisatie 24(2):101–120

Walumbwa FO, Luthans F, Avey JB, Oke A (2011) Retracted: authentically leading groups: the mediating role of collective psychological capital and trust. J Organ Behav 32(1):4–24

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the National Science Centre in Poland (the research grant no. DEC-2013/09/B/HS4/00498) is acknowledged by the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Basinska, B.A. (2017). Individual Resources and Intercultural Interactions. In: Rozkwitalska, M., Sułkowski, Ł., Magala, S. (eds) Intercultural Interactions in the Multicultural Workplace. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39771-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39770-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39771-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)