Abstract

This chapter provides the first comprehensive review of findings from studies using the recently developed questionnaire measuring effort-reward imbalance (ERI) in unpaid household and family work. First, we outline the relevance of stress related to household and family work for public health, and we describe the development of the modified questionnaire. Using data of a population-based study with 3129 women of underage children we subsequently report psychometric properties of our adopted ERI-instrument, including a short scale measuring over-commitment in domestic work. Then, we will consider whether effort-reward imbalance in domestic work is associated with impaired health among mothers. Based on the assumption that women’s intensity of stress experience in the homemaking role varies according to structural conditions, we explore the impact of distinct socio-economic and family conditions on ERI in household and family work. Finally, we discuss whether and to what extent the relationship between education and health is mediated by ERI in household and family work, thus contributing to the explanation of health inequalities in women. The chapter ends with a set of policy-directed recommendations on how to reduce the burden of domestic work and with some suggestions for further research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Household and Family Work: A Neglected Issue of Public Health Research

Compared to gainful employment, unpaid household and family work – mostly done by women – still receives little attention from the public as well as from public health research. Most of what is known today about the quality of women’s experiences in the homemaking role is drawn from research on fulltime homemakers conducted in the 1970s and 1980s. These studies predominantly stress the negative qualities of housework, including its fragmented, repetitive and demanding nature as well as the isolation and low social rewards associated with this role (Kibria et al. 1990). As Kibria notes “the neglect of homemaking as a topic of research reveals the implicit but widespread assumption that involvement in paid employment overwhelms the social and psychological significance of homemaking activities for women” (1990, p. 329). He concludes that while domestic work continues to hold an important place in women’s live, little is known about women’s experiences in the homemaking role and about the relationship of these experiences with women’s health. In line with this, Staland-Nyman et al. (2008) stated that future research needs to address strain in domestic work as a contributory factor to women’s ill-health. More recently, Molarius et al. (2014) pointed out that domestic work is highly important for population health and also for gender equity in health. They concluded that domestic work should not be omitted when considering factors that affect self-rated health. As a first step towards strengthening the visibility and importance of household and family work the WHO report on social determinants of health recommends to include unpaid work in national accounts (CSDH 2008).

In contrast to household and family work research on the reconciliation of work and family life has continuously grown over the last two decades. Due to increasing participation of women in the workforce, the focus was placed on the impact of multiple role occupancy, including the roles of parent, spouse and employee. Two major theories were put forward concerning the relation of multiple roles with well-being. The ‘role-stress-theory’ indicates that managing multiple roles is difficult and creates strain and conflicts between the demands of work and family. On the other hand, the ‘role-benefit-theory’ suggests that participation in multiple roles provides a larger range of opportunities and resources that can be used to promote better functioning in other live domains. Empirical evidence was found for the role-strain-theory (Glynn et al. 2009; Krantz and Östergren 2001) as well as the role-benefit-theory (McMunn et al. 2006; Fokkema 2002; Lahelma et al. 2002). However, the multiple-role-approach was criticized for a number of reasons. For example, it was claimed that work and family were considered unrelated to each other, while a growing body of research shed light on their interdependence (Tsionou and Konstantopoulos 2015). In addition, it was argued that in their roles as workers, spouses, and parents, women experience both suffering and gratification. Hence, rather the qualitative than the quantitative aspects of women’s experiences of social roles are important to understand their psychological well-being, or lack thereof (Baruch and Barnett 1986).

2 Measuring Qualitative Aspects of Household and Family Work

In order to capture the qualitative dimensions of domestic and family work, some scholars started to use similar models for the study of paid and unpaid work on health. Initially, the job strain model developed by Karasek and Theorell (1990) was applied to household and family work with the two central components of high job demands and low decision latitude (see Chap. 1). The findings showed that women reporting low control of their domestic work had increased risks of burnout (Kushnir and Melamed 2006), lower self-rated health (Staland-Nyman et al. 2008), depression and anxiety (Griffin et al. 2002) as well as coronary heart disease (Chandola et al. 2004).

More recently, the Effort-Reward-Imbalance-model (ERI) was adapted to unpaid household and family work as well. This approach defines women’s engagement in household and family not only as an additional social role beyond work, but also as a specific form of labour. Literature suggests that some crucial efforts of paid labour also apply to domestic work, in particular ‘time pressure’, ‘interruptions and disturbances’ and ‘pressure to work overtime’ (Glass and Fujimoto 1994; Lennon 1994). The underlying hypothesis claims that household and family work – similarly to paid employment – contributes to one’s social identity and social status. In addition, household and family work may also offer ‘rewards’ in terms of promoting self-esteem and may therefore provide the potential for experiencing a favourable self-concept. As Baruch and Barnett (1986) argued, the prevailing images of housework as purely burdensome may be overly simplistic. They pointed out that – very similar to the basic assumption of ERI at work – the balance between rewarding and stressful aspects of the homemaking-role seemed to be the best predictor of well-being. Siegrist (1998) stated that the principle of reciprocity may not be confined to paid work. It may be experienced in a similar way in other domains, such as marital and parental relationships. However, as Knesebeck and Siegrist (2003) pointed out, rewards in unpaid work compared to paid labour are rather of an emotional than an economic nature. This means that feelings of esteem, respect, appreciation and love rather than material benefits may be the most important reward transmitters in unpaid work (see Chap. 12). According to Baruch and Barnett (1986), women found the most rewarding aspects of the mother-role in the love they received by their children and pleasure in their accomplishments. They also identified aspects related to the partner as important, in particular having an emotionally supporting partnership. Studies suggest that women attaching a high priority on motherhood and taking care for the family showed higher values of satisfaction and well-being (Martire and Stephens 2000; Wickrama et al. 1995). Thus, the sense of doing something meaningful might be another important source of intrinsic reward. On the other hand, it was reported that household and family work are receiving insufficient recognition and social prestige, and the value of being housewife has significantly decreased over the last decades (Cox and Demmitt 2014; Glass and Fujimoto 1994).

3 ERI in Household and Family Work

Based on a literature-review, items were generated for measuring ERI in household and family work, abbreviated as ERI-HF (Sperlich and Geyer 2015c). The component ‘effort’ is composed of eight items referring to demanding aspects of household and family obligations by emphasizing quantitative workload. In the instructions of the questionnaire it was stated that “household and family work” covers a wide range of activities, including family organization, child care, help with homework, providing transportation for the children, as well as cooking, washing, tidying up, shopping, cleaning and much more. While ‘effort’ – analogous to ERI in paid work – was expected to show an unidimensional structure, ‘reward’ was assumed to be composed of four dimensions: (1) ‘affection from the child(ren)’, (2) ‘recognition from the partner’, (3) ‘intrinsic value of family and household work’ and (4) ‘societal esteem’.

Response formats were constructed in analogy to the original ERI. First, subjects may agree or disagree whether the item content describes a typical feature of their work situation. Subsequently, mothers who agree are asked to rate to what extent they usually feel distressed by this experience. Every item has five response categories ranging from (1) ‘does not burden me at all’ to (5) ‘burdens me greatly’.

In addition, the short version of the over-commitment questionnaire was adapted to household and family work that captures the personal characteristic of inability to withdraw from work obligations (Peter et al. 2006). Minor linguistic changes only were needed, but two items had to be excluded due to poor reliability. The modified over-commitment-questionnaire consists of four items with four response categories ranging from (1) ‘totally disagree’ to (4) ‘totally agree’. Up to now, the ERI-HF questionnaire and the modified scale ‘over-commitment’ were translated from German language into English and Brazilian Portuguese language (Rosembach de Vasconcellos et al. 2016).

Psychometric properties of the ERI-HF-questionnaire were tested in a population-based study of German mothers (n = 3129). Data were collected in 2009 by means of a mail survey. Finally 3183 women agreed to participate, corresponding to a response rate of 62.3 %. Overall, the sample can be considered as representative for German mothers in terms of German federal state, school education, mother’s age, marital status and number of children. The age of participating women varied between 17 and 60 years (mean age 39.1, SD = 6.8), and that of the youngest child ranged from 0 to 18 years (mean age 9.4, SD = 5.3). Most women (72.8 %) were married, 17.5 % were single mothers. 44.5 % of mothers had one, 42.6 % had two and 13 % had three and more children. About one out of three participants (32.6 %) attended the school for no more than 9 years, and 30.4 % had an income considered at risk of poverty (<60 % of the median equivalent income). For more information on socio-demographic and family-related characteristics see Sperlich and Geyer (2015a).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) reproduced the theoretical structure of ERI-HF: the ‘effort’-scale is based on one latent factor with eight items, whereas the scale ‘reward’ is composed of the expected four latent factors. With the exception of one item, ‘Reward2’, the model fit is appropriate with respect to standardized regression weights and squared multiple correlations (Fig. 13.1). Fit indices (χ2/df, RMSEA, GFI, AGFI) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) are satisfactory, indicating that the proposed theoretical construct fits the data. The same holds true for ‘over-commitment’, as evident from high internal consistency and satisfactory fit indices (Sperlich et al. 2012).

Factorial structure of ERI in household and family work with standardized regression weights (direction of the arrows to the right) and squared multiple correlations (direction of the arrows to the left and downward) (Source: Sperlich et al. 2012)

Analogous to Siegrist et al. (2004), the effort-reward ratio was computed for each respondent according to the formula: e/(r × c) where e is the sum score of the effort scale, r is the sum score of the reward scale (with reversed coding according to the notion of imbalance) and c defines a correction factor for different numbers of items in the nominator and denominator. The effort-score based on the eight items varies between 8 and 40 (highest distress-level), the reward-score varies between 11 and 55 (highest distress-level). Values close to zero indicate a favourable condition (relatively low effort, relatively high reward), whereas values above 1.0 indicate an effort-reward imbalance, e.g. a high amount of effort spent that is not met by the rewards received in turn.

About 19.3 % of mothers perceived lack of reciprocity in household and family work (Table 13.1). With regard to ‘effort’, high distress due to the ‘feeling as never being off duty’ was reported by every third mother and was therefore experienced as the most common stressor in household and family work. The rate of mothers reporting high distress due to effort was comparatively high, ranging from 17.2 % to 33.0 %. Lack of reward was less frequently experienced, with lack of ‘societal esteem’ reaching the highest degree of approval. Considering ‘over-commitment’, 23.8 % of mothers reached a sum score ≥12 suggesting a psychosocial risk condition. The items ‘I easily run into time pressures’ and ‘already in the morning I begin to worry about family work’ received highest approval rates (almost 60 %).

4 ERI in Household and Family Work and Women’s Health

At work, lack of reciprocity elicits strong negative emotions which in the long run adversely affect employees’ physical and mental health (see Chap. 1). A large body of evidence supports this assumption, indicating that an imbalance between high effort and low reward is associated with (psycho-) somatic symptoms, cardiovascular disease outcomes and psychological well-being (Siegrist 2009; Van Vegchel et al. 2005). We assumed that an imbalance in household and family work between efforts spent and subsequent rewards received may have adverse health consequences comparable to those associated with paid work.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were carried out in order to analyze the associations between ERI in domestic work and various health outcomes (anxiety and depression, somatic complaints, subjective health, hypertension) (Sperlich et al. 2012). Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale German Version (HADS-D) (Hermann-Lingen and Buss 2005). A modified version of von Zerssen’s complaints scale (v. Zerssen 1976) was used for assessing physical disabilities and discomfort. Subjective health was assessed by a single item with five response categories ranging from 1 (‘very poor’) to 5 (‘very good’). For measuring hypertension the mothers were asked if a doctor had ever diagnosed high blood pressure (response format ‘yes’ or ‘no’). As a predictor of health outcomes the effort-reward ratio was transformed into a binary variable (values ≤1 vs. > 1). In order to differentiate between mothers with slight, moderate, or marked imbalance, women with a ratio > 1 were divided into three equally sized groups: (1) ratio score ≤ 33th percentile (slight imbalance), (2) ratio score ranging from the 34th–65th percentile (moderate imbalance), and (3) ratio score with values above the 65th percentile (marked imbalance). For ‘hypertension’ as outcome, logistic regression was performed due to its categorical scale level. In order to eliminate confounding effects we controlled for mothers’ age, personality traits (optimism and over-commitment) and socio-demographic characteristics (income, school education, employment status, single motherhood, number of children and age of youngest child).

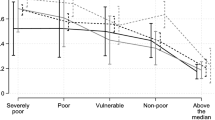

As Fig. 13.2 illustrates, there is a linear association between ERI and health outcomes such that health impairments are continuously increasing with ERI. The strongest association can be found for mental health: Mothers reporting no lack of reciprocity have significantly lower anxiety and depression levels as compared to those reporting high levels of imbalance. A similar, less pronounced trend is observed for somatic complaints and self-rated health. With respect to blood pressure, a marked imbalance is significantly associated with hypertension.

Associations of ERI with mother’s health outcomes. ANCOVA and logistic regression statistics adjusted for age, personality traits and socio-demographic characteristics.  none, ratio ≤1.0

none, ratio ≤1.0  slight, ratio ≤33th percentile

slight, ratio ≤33th percentile  moderate, ratio between the 34th and 65th percentile

moderate, ratio between the 34th and 65th percentile  marked, ratio ≥66th percentile (Source: Sperlich et al. 2012)

marked, ratio ≥66th percentile (Source: Sperlich et al. 2012)

In order to analyze the associations of ERI with health in more detail, we tested the following three main hypotheses in analogy to ERI at work (Siegrist 2002a):

-

1.

ERI is associated with health risks, whereby the effect of ERI is higher than the single effects of high effort and low reward,

-

2.

A high level of over-commitment may increase the risk of poor health even in the absence of ERI

-

3.

Mothers reporting ERI and a high level of over-commitment are at highest risk of poor health.

Using the same health indicators (except for hypertension), we performed logistic regression analyses calculating odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI). To investigate the first hypothesis, we estimated odds ratios of poor health for ERI and the two subscales separately, resulting in three regression models (Sperlich et al. 2013). In addition, we analyzed the effect of ERI before and after controlling for the separate effects of ‘effort’ and ‘reward’. Regarding the second hypothesis we evaluated over-commitment as an independent variable by controlling for ERI. Third, we analyzed whether mothers reporting an extrinsic ERI and a high level of over-commitment had an even higher risk of poor health. To this end both risk factors were combined into a single variable with four levels with ‘ERI ratio low and over-commitment low’ as reference group. All analyses were adjusted for pessimism, mother’s age, social status (school education, income), employment status and single motherhood (for more details see Sperlich et al. 2013).

In line with the first hypothesis, ‘high effort’ as well as ‘low reward’ are significantly associated with all health outcomes (for detailed results see Sperlich et al. 2013). Overall, the health-related impact of ‘high effort’ (ORs ranging from 3.14 to 7.09) is more pronounced than the effect of ‘low reward’ (ORs ranging from 2.71 to 4.36). The mismatch between high effort and low reward (ER-ratio) is also significantly associated with poor health. Partly in line with the first hypothesis the odds ratios of the ER-ratio for anxiety and depression were elevated also after including the single scales together with the ER-ratio. In contrast, this does not hold for subjective health. Similar results for ERI at work were reported by Preckel et al. (2007) and by Wahrendorf et al. (2012), demonstrating that the ER-ratio produces eventually, but not always a significant effect after controlling for the separate effects of ‘effort’ and ‘reward’. Consistent with the second hypothesis, a significant association of over-commitment with elevated health risks was found (ORs ranging from 1.71 to 3.79). Even after adjusting for ERI this association remained stable indicating that the inability to withdraw from household and family work may matter for women’s health. In line with the third assumption of the ERI model, mothers reporting an ER-ratio above 1.0 in combination with a high level of over-commitment are at highest risk of poor health with ORs ranging from 4.27 to 17.59. In sum, the main assumptions of the ERI model were largely confirmed by this study. Hence, it may be concluded that failed reciprocity in household and family work defines a state of emotional distress with negative health consequences, as evidenced by the original model of ERI at work (Sperlich et al. 2013).

5 The Impact of Social and Family-Related Factors on ERI in Household and Family Work

The evidence on construct validity suggests that ER-ratio scores increase with the number of children and decrease when children are getting older. In addition, socioeconomic position seems to affect the mismatch between requested efforts and given rewards. In particular low income is associated with higher effort and lower reward, resulting in higher ER-ratio scores. A high mismatch was also found for single mothers (Sperlich et al. 2012). However, the strength of relationships tends to be overestimated in bivariate analyses when the independent variables considered (such as income and single motherhood) are strongly correlated (Sperlich et al. 2011). Therefore, in a further study, we investigated the effects of all possible predictors simultaneously on the ERI components by means of regression analyses (Sperlich and Geyer 2015a). As we had no theoretical assumptions about the relative importance of the social and family-related factors considered, stepwise logistic regression analysis was used in an exploratory way. We assessed the degree to which strain-based-pressures in the work role impair performance in the family role (‘negative work-to-family spillover’) as a possible further predictor of ERI. To this end, three items from a previous study were included (e.g. “due to job strain I am often too tired for joint activities with my partner/my child/ren)” (Siegrist 2002b).

As expected, the number of variables that are significantly associated with the ERI-components decreased after considering all predictors simultaneously. However, family-related characteristics such as ‘age and number of children’ remained largely significant in the multivariate model, confirming that effort in household and family work decreases with children’s age and increases with number of children. In addition, low levels of ‘social support’, marked ‘negative work-to-family spillover’ and women’s statement to be ‘mainly responsible for household and family work’ remained significantly associated with higher odds of all ERI-components. By contrast, ‘socioeconomic position’ (school education, job position and per capita income) was less important in the presence of other social and family-related factors. However, the effects of ‘school education’ on the ‘ER-ratio’ and on the subscale ‘reward’ remained statistically significant in the multivariate approach. Further analyses on the four dimensions on reward revealed that ‘having older children’ and ‘having more than one child’ was significantly associated with high distress related to lack of affection from child. Lower levels of ‘perceived social support’ and holding the ‘main responsibility for household and family work’ proved to be powerful in explaining higher levels of distress related to all dimensions of reward. Similarly, marked ‘work-to-family spillover’ contributed to distress related to all reward-dimensions, in particular with respect to lack of intrinsic value, and lack of recognition from spouse. Working women tended to show lower odds of distress related to lack of societal esteem compared to fulltime-housewives. In addition, women with lower levels of socioeconomic position (education and income) showed significantly higher rates of stress due to lack of societal esteem of household and family work. This may indicate that the perception of domestic work as a low-prestige activity is a source of stress, particularly among socially disadvantaged women (Sperlich and Geyer 2015a).

6 Stress in Household and Family Work: A Factor Contributing to Health Inequalities in Women?

Research on social inequalities in health suggests that the socio-economic gradient in health is less steep in women than in men. In particular, occupational position proved to be less relevant in explaining health inequalities among women (Sacker et al. 2000; Arber 1997; Koskinen and Martelin 1994). Chandola et al. (2004) assumed that the main mechanisms underlying social inequalities in health may differ between men and women: while employment-related factors may be more important for men, women may have other potentially demanding social roles related to family, child-care and care taking of others. Supporting this assumption, we found stress in household and family work in terms of ERI being significantly associated with mother’s adverse health. In addition, we demonstrated that socially disadvantaged mothers perceive higher stress due to lack of societal esteem of the homemaking role. If both findings are considered in combination the question emerges whether stress in household and family work may contribute to health inequalities in women.

In order to address this issue, we analyzed ERI in household and family work as a mediator in the relationship between low socioeconomic position (as measured by school education) and women’s somatic complaints (Sperlich and Geyer 2015b). Effort-reward imbalance (ERI) in household and family work acts as a mediator if school education exerts significant effects on somatic complaints and on ERI, and if ERI is assumed to have an impact on somatic complaints (Holland 1988). The regression coefficients and their 95 % confidence intervals of the total and direct effects as well as the indirect effects via ERI (mediator effect) were estimated by means of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses. We calculated five different mediator models according to different ERI components. For all analyses, we controlled for age, employment status, occupational stress, perceived social support and the personality trait ‘optimism/pessimism’ as possible confounders. Inference about indirect effects was determined by 95 % bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 1.000 bootstrap samples. If zero was not in the confidence interval, the indirect effect was different from zero and considered as significant. In addition, the Sobel Test (normal theory test) was used to specify the p-value of indirect effects.

Our analyses revealed a significant total effect of education (X) on somatic complaints (Y) (Fig. 13.3). As expected, higher levels of education are associated with lower levels of somatic complaints (total effect = −0.46). Adjusting for the effort-reward ratio (Model 1) only slightly reduced the magnitude of the association between education and somatic complaints to β = −0.42 (direct effect). No significant indirect effect of X on Y through the effort-reward ratio can be found (indirect effect = −0.04). However, by considering ‘effort’ (Model 2) and ‘reward’ (Model 3) separately, significant indirect effects are observed for both subscales. The effects have very different directions, thus canceling each other out, resulting in a statistically insignificant ER-ratio. Adjustment for ‘effort’ leads to increased educational differences in somatic complaints (β = −0.63). On the other hand, adjustment for ‘reward’ resulted in a marked reduction of the association between school education and somatic complaints (β = −0.31). Regarding the reward dimensions, we found a significant indirect effect for ‘societal esteem’ (β = −0.15) and for ‘affection from the child(ren)’ (β = −0.03) (Model 4). With regard to ‘intrinsic value’ the effect was slightly above statistical significance (p = 0.073) while ‘recognition from spouse’ (Model 5) clearly failed to exert a significant indirect effect (p = 0.407).

The mediating effects of ERI and its components on the relationship between school education and somatic complaints (Source: The diagram is based on Sperlich and Geyer 2015b). Notes: *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05. Model 4 includes all reward dimensions except ‘recognition from spouse’, Model 5 contains ‘recognition from spouse’ (not applicable to single mothers) with decreased sample size and reduced total effect size (β = 0.41)

Our findings demonstrate that the ERI-components have different effects on somatic complaints. Contrary to our expectation, the regression coefficient for ‘effort’ was positive, indicating that higher educated women are more affected by extensive workload from household and family duties than lower educated women. A possible explanation may be that higher educated mothers are more committed to paid work (Gutiérrez-Domènech 2005). Therefore they may be more susceptible to work-family conflicts (negative work-to-family spillover) – fact that may explain their higher level of effort in household and family work. However, after controlling for negative work-family spillover, the effect of education on effort slightly decreased but remained statistically significant (Sperlich und Geyer 2015b). Thus, it can be assumed that work-to-family conflicts do not sufficiently explain increased effort levels among higher educated women. Contrary to ‘effort’, ‘reward’ was positively associated with school education. Our findings suggest that less well educated mothers perceive less appreciation and affection from their children which may reflect difficulties with parenting and mother-child relationship.

As Artazcoz et al. (2004) pointed out, the effects of parenthood on health depend on socioeconomic resources. While family work may be an important source of emotional distress for women of lower educational level, children mainly mean a source of satisfaction for women with high levels of material well-being. In supporting of this assumption, Conger and Donnellan (2007) found difficulties with parenting to occur more frequently in socially disadvantaged mothers. While the impact of parent-child relationship on children’s cognitive and emotional growth has been the subject of extensive research (e.g. Yunus and Dahlan 2013) its implications for women’s well-being received less attention. Our results support the assumption that the quality of mother-child relationship is an important determinant of women’s health as well.

In addition, we found that less educated women raised more often doubts about the meaningfulness of domestic and family work. Although failing to reach statistical significance, this finding suggests that lower educated women experience less satisfaction in the homemaking-role. In line with this interpretation they more often complained about a lack of ‘societal esteem’ for their household and family work. This may be related to the fact that they are more often fulltime-housewives. In our study, this was the case in almost every fourth lower educated mother (24.6 %), whereas only one out of ten (10.6 %) of the higher educated women stayed at home. According to the ‘role-benefit theory’, employment is beneficial because it provides women with a wider set of identities (Pavalko et al. 2007; Martikainen 1995). Thus, lower educated women might perceive higher distress related to low societal esteem as they have insufficient means for compensating negative experiences in the homemaking-role by other more satisfying role involvements.

In sum, we found some evidence that the association of women’s education with somatic complaints is mediated by stress related to low reward for household and family work. In particular, lack of societal recognition, but also lack of affection from the children and lack of intrinsic value of being mother and housewife, contribute to the explanation of higher levels of somatic complaints in lower educated women. After adjustment for all reward dimensions, the associations between education and women’s somatic complaints were no longer statistically significant. Therefore, we might conclude that stress due to lack of reward for household and family work is a contributing factor to health inequalities in women.

7 Concluding Remarks

This chapter is devoted to findings obtained from studies conducted with a questionnaire measuring effort-reward imbalance in unpaid household and family work. Our results support the assumption that the ERI-model is suitable for unpaid work and that it provides an explanatory framework for assessing stress experiences of family work. Particularly among socially disadvantaged mothers, lack of social recognition in the homemaking role proves to be a relevant source of psychosocial stress which may contribute to health inequalities in women. Given these findings, we conclude that future research on health inequalities should take into account stress related to household and family work in addition to other more established factors.

Before we turn to policy implications and future research perspectives, some important limitations of our findings need to be addressed. First, in line with literature (see Chap. 1) we assume that ERI is predicting health rather than health predicting ERI. However, the cross-sectional design of our studies precludes any causal inference. Hence, longitudinal studies are warranted in order to clarify the direction of causality. Second, as all analyses so far are based on subjective data, individual differences in personality traits may have affected the reporting of family-related stress and of subjective health. In order to minimize this possible ‘common method bias’, we controlled for optimism as one particular personality trait, demonstrating that this bias is unlikely to account for the observed associations. However, other potential sources of common method bias may need to be considered (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Finally, as our data are based on samples of mothers from Germany, the question arises whether our findings can be generalized beyond this context. As countries differ with respect to their cultural norms and family policies (Palència et al. 2014), future research will benefit from cross-country comparisons.

7.1 Policy Implications for Promoting Women’s Health

Since the reunification in 1990, family policies in Germany gradually changed from traditional carer-strategy (men as ‘breadwinners’, women as ‘caregivers’) to the earner-carer-strategy where women and men are treated as being equally involved in both earning and caring (Bertram and Bujard 2012). Alongside this transformation, the societal value of being a fulltime-housewife has significantly lost its prestige (Cox and Demmitt 2014). Even though a number of women still stay at home, fulltime-homemakers are increasingly perceived as ‘old-fashioned’. We found lower educated mothers to complain more often about lack ‘societal esteem’ for their household and family work than those with higher education – a fact that may be attributable to their high prevalence of being fulltime-housewives. As demonstrated elsewhere (Sperlich et al. 2011), lower educated women also have more children and bear their first child earlier in life compared to higher educated women. Our findings suggest that lower educated women are particularly affected by lack of social recognition as they remain more affiliated with the traditional gender role. They also raise more often doubts about the meaning of household and family work as compared to higher educated women, indicating that they are also less satisfied with their job at home. Hence, we might suppose that their fulltime-homemaking role is not always chosen voluntarily, but in part reflects a lack of occupational opportunities. In this respect, future interventions should aim at improving the labor market integration of low-educated and low-skilled women. However, as Glass and Fujimoto (1994) pointed out, employment can be considered as health promoting as long as overload does not outweigh its positive effects. Thus, not all mothers will necessarily benefit from employment. Family policies that are fostering free choice between paid work and household and family work (particularly in case of caring for very young children) (Misra et al. 2007) appear to be the most appropriate strategy for promoting women’s well-being.

In the former Federal Republic of Germany (Western Germany, GFR) the government was in favor of a policy where women were treated primarily as carers (Misra et al. 2007; Gustafsson et al. 1996). This policy explicitly rewarded women for providing childcare through measures such as long periods of parental leave and tax benefits, leading to gender segregation of work with men as the ‘breadwinner’ and women as being responsible for family obligations. By contrast, the former German Democratic Republic (Eastern Germany, GDR) fostered fulltime employment of mothers and provided a comprehensive childcare infrastructure. As a consequence, in the former GDR women and men showed nearly the same employment patterns. In the past 25 years following the reunification, family policies were the same in the Eastern and Western parts of Germany. However, employment patterns of women with preschool children still differ systematically in both regions, showing considerable higher rates in East as compared to West Germany. According to Pfau-Effinger and Smidt (2011), gender differences in the division of labor can largely be explained by differences in the cultural values that have developed differently in Western and Eastern Germany after the Second World War.

Remarkably, we also found different patterns of effort-reward imbalance in household and family work among women in East and West Germany. Whereas in the Western part 20.3 % of mothers reported an imbalance between high effort and low reward, this applied only to 13.5 % of East German mothers (Sperlich 2014). Levels of demand turned out to be approximately the same among East and West German mothers. Hence, ‘effort’ could not account for the observed difference. By contrast, West German mothers showed significant higher levels of distress related to lack of reward, specifically ‘societal esteem’, ‘intrinsic value’ and ‘affection from child’. We found that lower school education and lower labor participation rates are important mediators of these associations, thus contributing to distress attributable to low reward among West German mothers. In addition, we found that only 17.1 % of West German women stated that household and family work was shared equally between partners as compared with 32.3 % of East German women. Hence, gender inequity of household labor might be a further factor in explaining the observed differences between women in Eastern and Western Germany (Sperlich 2014). These findings suggest that family policies should not only aim at improving participation of women in the labor market, but also aim at promoting changes of gender roles towards a more equal sharing of paid and unpaid work between both parents (Mellner et al. 2006).

7.2 Stress in Household and Family Work: An Important Issue Also for Men?

Along with the increasing labor force participation of mothers, attitudes on gender roles gradually changed to the benefit of more equal role expectations. In Germany, some 20 % of fathers are currently identified as having a ‘modern’ gender role orientation (Volz and Zulehner 2009). These ‘new fathers’ are expected to be more fully engaged in the physical and emotional care of children and in developing more egalitarian relationships with their partners (Cabrera et al. 2000). As a consequence, men are increasingly expected to face household and family stress and a double burden of paid and domestic labor. So far, the adopted questionnaire ERI-HF was exclusively used among women in childcare responsibility. However, recently the ERI-model of household and family was tested with a clinical sample of fathers attending a family-focused rehabilitation (Sperlich et al. 2016). It provides specific treatments for mothers, and since 2002 for fathers as well, in childcare responsibilities. The data collection took place in 2014 in 14 institutions (n = 415). Confirmatory factor analyses revealed good to satisfactory properties for ERI as well as for over-commitment. Overall, 13.4 % of men in childcare responsibility reported an imbalance between high effort and low reward of household and family work, whereby levels of effort were more frequently present than stress due to low reward. In addition, a significant proportion of fathers had difficulties to withdraw from housework obligations. ERI in household and family work revealed to be significantly associated with father’s health. Our preliminary findings suggest that the instrument is applicable to men in childcare responsibility. Further studies have to show whether ERI in household and family work also contribute to our understanding of the social determinants of men’s health.

References

Arber, S. (1997). Comparing inequalities in women’s and men’s health: Britain in the 1990s. Social Science & Medicine, 44, 773–787.

Artazcoz, L., Artieda, L., Borrell, C., Cortes, I., Benach, J., & Garcia, V. (2004). Combining job and family demands and being healthy: What are the differences between men and women? European Journal of Public Health, 14, 43–48.

Baruch, G. K., & Barnett, R. (1986). Role quality, multiple role involvement, and psychological well-being in midlife women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 578–585.

Bertram, H., & Bujard, M. (2012). Zur Zukunft der Familienpolitik (The future of family policy). In H. Bertram & M. Bujard (Eds.), Zeit, Geld, Infrastruktur – zur Zukunft der Familienpolitik (Soziale Welt Sonderband, Vol. 19, pp. 3–24). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Cabrera, N. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bradley, R. H., Hofferth, S., & Michael, E. L. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71, 127–136.

Chandola, T., Kuper, H., Singh-Manoux, A., Bartley, M., & Marmot, M. (2004). The effect of control at home on CHD events in the Whitehall II study: Gender differences in psychosocial domestic pathways to social inequalities in CHD. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1501–1509.

Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199.

Cox, F. D., & Demmitt, K. (2014). Human intimacy – Marriage, the family, and its meaning (11th ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

CSDH. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Fokkema, T. (2002). Combining a job and children: Contrasting the health of married and divorced women in the Netherlands? Social Science & Medicine, 54, 741–752.

Glass, J., & Fujimoto, T. (1994). Housework, paid work, and depression among husbands and wives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 179–191.

Glynn, K., Maclean, H., Forte, T., & Cohen, M. (2009). The association between role overload and women’s mental health. Journal of Women‘s Health, 18, 217–223.

Griffin, J., Fuhrer, R., Stansfeld, S. A., & Marmot, M. (2002). The importance of low control at work and home on depression and anxiety: Do these effects vary by gender and social class? Social Science & Medicine, 54, 783–798.

Gustafsson, S. S., Wetzels, C., Vlasblom, J. D., & Dex, S. (1996). Women’s labor force transitions in connection with childbirth: A panel data comparison between Germany, Sweden and Great Britain. Journal of Population Economics, 9, 223–246.

Gutiérrez-Domènech, M. (2005). Employment after motherhood: A European comparison. Labour Economics, 12, 99–123.

Herrmann-Lingen, Ch., & Buss, U. (2005). Hospital anxiety and depression scale: deutsche Version; HADS-D – ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Angst und Depressivität in der somatischen Medizin. Testdokumentation und Handanweisung (Hospital anxiety and depression scale: German version; HADS-D, a questionnaire for the assessment of anxiety and depression in somatic medicine. Documentation and manual). 2nd Edition. Hans Huber, Hogrefe, Bern.

Holland, P. W. (1988). Causal inference, path analysis, and recursive structural equations models. Sociological Methodology, 18, 449–484.

Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work. Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.

Kibria, N., Barnett, R. C., Baruch, G. K., Marshall, N. L., & Pleck, J. H. (1990). Homemaking-role quality and the psychological well-being and distress of employed women. Sex Roles, 22, 327–347.

Knesebeck, O., & Siegrist, J. (2003). Reported non-reciprocity of social exchange and depressive symptoms. Extending the model of effort-reward imbalance beyond work. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 209–214.

Koskinen, S., & Martelin, T. (1994). Why are socioeconomic mortality differences smaller among women than among men? Social Science & Medicine, 38, 1385–1396.

Krantz, G., & Östergren, P. O. (2001). Double exposure: The combined impact of domestic responsibilities and job strain on common symptoms in employed Swedish women. European Journal of Public Health, 11, 413–419.

Kushnir, T., & Melamed, S. (2006). Domestic stress and well-being of employed women: Interplay between demands and decision control at home. Sex Roles, 54, 687–694.

Lahelma, E., Arber, S., Kivelä, K., & Roos, E. (2002). Multiple roles and health among British and Finnish women: The influence of socioeconomic circumstances. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 727–740.

Lennon, M. C. (1994). Women, work, and well-being: The importance of work conditions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 235–247.

Martikainen, P. (1995). Women’s employment, marriage, motherhood and mortality: A test of the multiple role and role accumulation hypotheses. Social Science & Medicine, 40, 199–212.

Martire, L. M., & Stephens, M. A. P. (2000). Centrality of women’s multiple roles: Beneficial and detrimental consequences for psychological well-being. Psychology and Aging, 15, 148–156.

McMunn, A., Bartley, M., Hardy, R., & Kuh, D. (2006). Life course social roles and women’s health in mid-life: Causation or selection? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 484–489.

Mellner, C., Krantz, G., & Lundberg, U. (2006). Symptom reporting and self-rated health among women in mid-life: The role of work characteristics and family responsibilities. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 1–7.

Misra, J., Moller, S., & Budig, M. (2007). Work-family policies and poverty for partnered and single women in Europe and North America. Gender & Society, 21, 804–827.

Molarius, A., Granström, F., Lindén-Boström, M., & Elo, S. (2014). Domestic work and self-rated health among women and men aged 25–64 years: Results from a population-based survey in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42, 52–59.

Palència, L., Malmusi, D., De Moorteld, D., Artazcoz, L., Backhans, M., Vanroelen, C., & Borrell, C. (2014). The influence of gender equality policies on gender inequalities in health in Europe. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 25–33.

Pavalko, E. K., Gong, F., & Long, J. S. (2007). Women’s work, cohort change, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 352–368.

Peter, R., Hammarström, A., Hallqvist, J., Siegrist, J., Theorell, T., & SHEEP Study Group. (2006). Does occupational gender segregation influence the association of effort-reward imbalance with myocardial infarction in the SHEEP study? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 34–43.

Pfau-Effinger, B., & Smidt, M. (2011). Differences in women’s employment patterns and family policies: Eastern and western Germany. Work and Family, 14, 217–232.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Preckel, D., Meinel, M., Kudielka, B. M., Haug, H. J., & Fischer, J. E. (2007). Effort-reword-imbalance, overcommitment and self-reported health: Is it the interaction that matters? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 91–107.

Sacker, A., Firth, D., Fitzpatrick, R., Lynch, K., & Bartley, M. (2000). Comparing health inequality in men and women: Prospective study of mortality 1986–96. BMJ, 320, 1303–1307.

Siegrist, J. (1998). Reciprocity in basic social exchange and health: Can we reconcile person-based with population-based psychosomatic research? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45, 99–105.

Siegrist, J. (2002a). Effort-reward imbalance at work and health. In P. L. Perrewé, J. Halbesleben, C. Rose (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well-being. Historical and current perspectives on stress and health 2, (pp. 261–291). Amsterdam: Boston.

Siegrist, J. (2002b). Soziale Reziprozität und Gesundheit – eine exploratorische Studie zu beruflichen und außerberuflichen Gratifikationskrisen. (Reciprocity in social exchange and health – an exploratory study for assessing effort-reward imbalance in work and outside work). Abschlussbericht zum Projekt C1; Projektzeitraum: 01.01.2000 bis 31.12.2001, Düsseldorf.

Siegrist, J. (2009). Unfair exchange and health: Social bases of stress-related diseases. Sociological Theory, 7, 305–317.

Siegrist, J., Starke, D., Chandola, T., Godin, I., Marmot, M., Niedhammer, I., & Peter, R. (2004). The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1483–1499.

Sperlich, S. (2014). Gratifikationskrisen in der Haus- und Familienarbeit – Gibt es Unterschiede zwischen ost- und westdeutschen Müttern? (Effort-reward imbalance in household and family work – are there differences between East and West German mothers?). Praxis Klinische Verhaltensmedizin und Rehabilitation, 93, 21–39.

Sperlich, S., & Geyer, S. (2015a). The impact of social and family-related factors on women’s stress experience in household and family work. International Journal of Public Health, 60, 375–387.

Sperlich, S., & Geyer, S. (2015b). The mediating effect of effort-reward imbalance in household and family work on the relationship between education and women’s health. Social Science & Medicine, 131, 58–65.

Sperlich, S., & Geyer, S. (2015c). ERI-HF. Fragebogen zur Messung von Gratifikationskrisen in der Haus- und Familienarbeit (ERI-HF. Questionnaire for the assessment of effort-reward imbalance in household and family work). In D. Richter, E. Brähler, & J. Ernst (Eds.), Diagnostische Verfahren für Beratung und Therapie von Paaren und Familien (Diagnostik für Klinik und Praxis 1st ed., Vol. 8, pp. 146–150). Göttingen: Hogrefe Verlag.

Sperlich, S., Arnhold-Kerri, S., & Geyer, S. (2011). What accounts for depressive symptoms among mothers? The impact of socioeconomic status, family structure and psychosocial stress. International Journal of Public Health, 56, 385–396.

Sperlich, S., Peter, R., & Geyer, S. (2012). Applying the effort-reward imbalance model to household and family work. A population based study of German mothers. BMC Public Health, 12, 12.

Sperlich, S., Siegrist, J., & Geyer, S. (2013). The mismatch between high effort and low reward in household and family work predicts impaired health among mothers. European Journal of Public Health, 23, 893–898.

Sperlich, S., Barre, F., Otto, F. (2016). Gratifikationskrisen in der Haus- und Familienarbeit – Teststatistische Prüfung des Fragebogens an Vätern mit minderjährigen Kindern. (Effort-reward imbalance in household and family work – Analysing the psychometric properties among fathers of underage children). Psychotherapy Psychosomatic Medicine, 66, 57–66.

Staland-Nyman, C., Alexanderson, K., & Hensing, G. (2008). Associations between strain in domestic work and self-rated health: A study of employed women in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36, 21–27.

Tsionou, T., & Konstantopoulos, N. (2015). The complications and challenges of the work-family interface: A review paper. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 593–600.

Van Vegchel, N., Jonge, J., Bosma, H., & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Reviewing the effort-reward imbalance model: Drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 1117–1131.

Vasconcellos, I. R. R., Griep, R. H., Portela, L., Alves, M. G. M., Rotenberg, L. (2016). Transcultural adaptation to Brazilian Portuguese and reliability of the effort-reward imbalance model to household and family work. Revista de Saúde Pública, 50 (in press).

Volz, R., & Zulehner, M. (2009). In BMFSFJ (Ed.), Männer in Bewegung. Zehn Jahre Männerentwicklung in Deutschland (Men on the move. Ten years of male development in Germany) (Forschungsreihe Band, Vol. 6). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Wahrendorf, M., Sembajwe, G., Zins, M., Berkman, L., Goldberg, M., & Siegrist, J. (2012). Long-term effects of psychosocial work stress in midlife on health functioning after labor market exit -results from the GAZEL study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 471–480.

Wickrama, K., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Matthews, L. (1995). Role identity, role satisfaction, and perceived physical health. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58, 270–283.

Yunus, K. R. M., & Dahlan, N. A. (2013). Child-rearing practices and socio-economic status: Possible implications for children’s educational outcomes. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 251–259.

Zerssen, D. v. (1976). Die Beschwerden-Liste (The list of complaints). Manual. Weinheim: Beltz.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this chapter was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant number GE 1167/7-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sperlich, S., Geyer, S. (2016). Household and Family Work and Health. In: Siegrist, J., Wahrendorf, M. (eds) Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32937-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32937-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-32935-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-32937-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)