Abstract

This chapter examines the role of public private partnerships in the public procurement of public real estate and transportation infrastructure in Germany. Introductory, the general structure and characteristics of PPPs are explicated along with special remarks about specific features of the German PPP approach. This includes the specific role of the financing models applied, especially the role of non-recourse forfeiting of instalments in municipal projects. Further reference is made to the highly divided and complex approach of federal and federal states’ authorities to PPPs. Any federal state set up its very own taskforce that issues guidelines and provides support to municipalities in heterogeneous ways. Nevertheless, on project level, a certain degree of standardization led to different types of contract models in the public real estate sector that are applied consistently throughout Germany on any governmental level. Although, even standardized, models in the road infrastructure sector are applied only on federal level, whereas single projects on state and municipal level can still be considered ‘pilot projects’. Finally, the flow of deals in the public real estate and the road infrastructure sectors are summed up in tables that also feature updated figures for projects in tendering and under preparation.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the wider context of public real estate, public private partnerships have become an established approach to public procurement of public real estate and transportation infrastructure in Germany. The general structure and characteristics of PPPs as well as special remarks about specific features of the German PPP approach will be explicated. Special reference is made to the flow of deals in the PPP market to point out the role of this procurement method in the German landscape of public real estate procurement.

2 Structure and Main Characteristics of PPP

PPP-Models have become an established procurement method in Germany since 2003. By means of PPPs, public bodies have procured projects in several different sectors. The sectors include public real estate (town halls, schools and the like) as well as public infrastructure, such as highways or federal roads. Even if the understanding of PPP may vary more or less from federal state to federal state and often also from sector to sector in Germany and in the sectors mentioned above the term PPP refers to a long-term, contractually regulated cooperation between the public and private sector for the efficient fulfilment of public, non-sovereign tasks. Necessary resources of the partners, such as their expertise, operational funds, capital, staff and risk management capabilities are brought into the project complementarily.

The main resulting characteristics and benefits of PPPs for the public that are expected to be derived from the definition above and are summarized as follows:

-

Efficiency gains through sharing tasks and responsibilities (sovereign tasks remaining with the public bodies whereas operational tasks are transferred as far as possible to the private).Footnote 1

-

Incentive mechanisms through life-cycle approach, long-term contractual relationship and private investments.

-

Innovative service delivery through application of output specifications, service levels agreements and performance-related payment mechanisms.

-

Faster project delivery, lower public budget burdening and higher public budget liquidity.Footnote 2

A particular benefit of PPPs for the private partner—especially construction companies as strategic investors—may be the possible implementation of diversification strategies, in order to relief their heavy dependency from economic cycles. Nevertheless, private partners need to build up expertise to cover the complete value chain of PPPs. Predominantly, construction companies have to extend their value creation with operation and maintenance services. In the past, several construction companies developed skills and capacities and built up knowledge to become leading actors on the realizing side of the market.

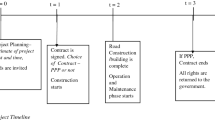

A typical structure of a PPP project with its different stakeholders and their mutual contractual relationships is shown in Fig. 1.

Contractual relations in the basic PPP-Model. Source: Weber et al. (2006), pp. 31 and 37

The SPC (later in this section as referred to the ‘private partner’) plays the pivotal role in the set up of a PPP structure. The SPC holds all the relevant contracts with a set of different contract partners. First and foremost, the PPP-Project agreement between the implementing public body and the SPC rules the scope of the services to be procured, the means of service delivery and payment mechanisms. The shareholder agreement rules all the rights and duties between the shareholders of the SPC. This includes the take-over of tasks (construction/operation, etc.), the distribution of dividends from the SPC to the shareholders and the allocation of risks. The latter is a crucial point in the eyes of the debt creditors, so that the loan agreement rules responsibilities between the SPC and their shareholders and the debt providers. More explanations to the financing of PPP-Projects are made in the next section of this document. Furthermore, the advisory agreement, the GC-agreement (general contractor), the operation/service agreement and possible off-take/supply agreements rule special tasks. These tasks are commissioned to special subcontractors, who design, build, supply and operate the PPP-project on behalf of the SPC. As most of the risks are allocated to the subcontractors, the SPC stands almost free of risks, in order to satisfy the debt providers and the shareholders of the SPC.

3 Financing of PPP-Projects

In Germany, the application of PPP models is bound to the use of specific financing models. While in the UK and internationally, project finance is the most common mode of financing PPPs, in Germany and France so-called forfeiting models are commonly used, too and predominantly applied in social infrastructure. The differences between these models are described in following. Later in this section, major distinctions between PPP-Projects in terms of the incoming cash flows depending on the demand or the availability of the assets, the stage of the project at the time of investment as well as Greenfield or Brownfield characteristics will be explained.

Main characteristic of project finance is that the involved creditors develop risk-reflecting, stable financing structures that are based on expected cash flows and capital structure of the SPC, abilities and risk management capabilities of the project initiators. Figure 2 shows the structure of project finance for PPP-Projects. The creditors determine the conditions of the capital commitment and the funds are paid directly to the SPC.Footnote 3 Further characteristics of project finance are limited-recourse structures, which determine the distribution of credit risks between the creditors and equity providers and the leverage-effect, who requires a high level of debt.Footnote 4 As the creditors concentrate on the expected cash flows for the SPC’s debt service, cash flow related lending itself is focused on free cash flows. Free cash flows are the benchmark to rate the SPC’s future financial situation, because project finance implies the valuation of returns instead of the valuation of assets.Footnote 5 The whole structure of one project finance consists of several credits, which are suited to the financial situation of the SPC over the contract term. Concluding, different types of credits are paid out to the SPC for different investments with different risk profiles, e.g. the construction stage is riskier that the operation stage of one PPP-Project. Because of the financing structure reflecting specific project risks, the financing structure of SPC’s vary depending on the risk exposition of the free cash flow. Typically, the equity-ratio ranges from 8 to 30 %, whereby SPCs in projects with high market risks might be forced to equity-ratios up to 50 %.Footnote 6 Finally, a high equity-ratio indicates insufficient leeway of the SPC.Footnote 7

Financing model: project finance. Source: Alfen Consult GmbH (2010)

Alternatively, small projects in Germany might be financed with a non-recourse forfeiting of instalments instead of project finance. Figure 3 shows the structure of non-recourse forfeiting of instalments for PPP-Projects. The overall financing costs of a forfeiting solution compared to a project finance solution are lower for two reasons. One reason yields from lower cost of equity, because forfeiting models require minimal equity investments. Another reason yields from forfeiting instalments. This means that the price of debt is lower, because the model features a credit risk transfer from the bank to the public body. In summary, the capital structure of the SPC shows very little equity, because the credit risk is borne by the public body. In addition, yield spreads for project risks are minimized and the price of debt is 5–20 bps higher than common loans taken by municipal bodies.Footnote 8 Forfeiting the instalments includes the non-recourse sale of the SPC’s debt claims from the bank to the public body. In PPP-Projects, the public body pays for the construction of the project without the right to withhold payments due to poor contractor performance.Footnote 9 Hence, the public body also bears the risk of bankruptcy of the contractor.

Financing model: forfeiting model (non-recourse forfeiting of instalments). Source: Alfen Consult GmbH (2010)

In total, 70 % of the projects featured forfeiting of instalments, whereby representing 33 % of total investments. Projects featuring project finance represent 20 % of the projects and 61 % of the total investments. In recent years, the terms ‘four-phase’ and ‘three-phase’ PPP-Projects were introduced to include and to distinguish projects where private finance is either part of the tasks of the private partner over the full contract term or just includes financing of the construction phase.Footnote 10

4 Institutional Set Up for PPPs in Germany

After erratic developments until 2009, the institutional set up for PPPs in Germany is founded on solid grounds. In 2009, the Federal PPP Task Force within the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs (BMVBS) was closed and its tasks were shifted to the ‘Partnerschaften Deutschland—ÖPP Deutschland AG’, the new Federal PPP Task Force within the Ministry of Finance (BMF). Main objectives of Partnerschaften Deutschland (PD) are to advise and support exclusively implementing public bodies and to adopt PPP structures to new sectors. Furthermore, PD also supports the harmonization of PPP standards in the federal system and in different sectors, based on specific working committees that hold regular meetings together with the PPP competence centers on federal state level. General standardization, harmonization of guidelines on federal and federal state levels and the exchange of experiences are to be achieved successfully in these new structures.Footnote 11

On federal state level, there are PPP competence centers in every federal state, whose objectives are to support and advise local municipalities wishing to implement new PPP-Projects. The institutional set up and integration into local and state administration are varying, as can be seen in Fig. 4.

German PPP task forces on state level. Source: http://www.bmvbs.de/SharedDocs/DE/Artikel/UI/kompetenzzentren-und-ansprechpartner-der-laender.html (as of 27.09.2010)

Most of the institutions at federal state level are integrated in the State Ministries of Finance, which is in line with the most successful approach for a quick and sustainable development of PPP internationally. The PPP Task Force of North Rhine Westphalia had taken a leading role in publishing basic groundwork in term of numerous PPP guidelines. Following institutions in other federal states adopted their institutional set up and their approach to support and advise municipal authorities to set up new PPP-Projects. The PD and federal state PPP institutions are focused on public real estate projects like schools, universities, administration buildings, hospitals, prisons, etc. Hence, most PPP-Projects were realized in the public real estate sector.

In the road sector, the institutional set up differs from the one in the real estate sector in parts. While road projects on federal state and municipal levels might be supported by PPP competence centers on federal state level, federal road projects are supported by the Verkehrsinfrastrukturfinanzierungsgesellschaft (VIFG). The VIFG is a special body of the BMVBS that manages the federal transportation-funding budget. Apart from the task to supervise the operator of the toll levying system for heavy goods vehicles (HGV) on German highways, the VIFG distributes toll revenues among the annual budget to fund works on roads, railways and waterways. The tasks of the VIFG are laid down and specified in a special law. They cover the distribution of the revenues from the HGV-toll and of revenues from inland waterway transportation in order to finance federal transportation projects in the sectors of road, rail and inland waterway transportation.Footnote 12 Furthermore, the VIFG is responsible for the preparation and execution of PPP-Projects in the above named sectors.

5 Applied Contract Models

Applied contract models in public sector procurement by the means of PPPs in Germany vary in wide ranges. However, models in the public real estate and road infrastructure sectors are inconsistent. This also applies for project executing authorities, both due to the federal system in Germany.

The different models applied in public real estate are:Footnote 13

-

PPP-Owner-Model

-

PPP-Purchaser-Model

-

PPP-FM-Leasing-Model

-

PPP-Renting-Model

-

PPP-Concession-Model

-

PPP-Joint-Venture-Model

In the following, each of models will be described in brief. The six PPP contract models named above are defined in the ‘Federal Report on PPP in Public Real Estate’.Footnote 14 Jointly, the models are based on the life cycle approach featuring design, construction, financing and operation of the projected assets. Differences between the models affect ownership of the asset prior to, during, and after the contract term, the reimbursement/payment mechanisms and the utilization of the assets. Undisputedly the type of the model, the implementing public body pays the private partner a periodical remuneration to cover the cost of construction, financing and operation as well as risks and profit.

-

Most PPP-Projects in social infrastructure are realized through the application of the so-called PPP-Owner-Model (design-build-finance-operate-transfer). In this model, the implementing public body remains the owner of the assets and the private partner takes over the life-cycle tasks design, construction, financing and operation of the assets. Throughout the contract term of 15–25 years, the private partner bears most of the risks except for realization risks and market risks. The PPP-Owner-Model is predominantly applied to school projects and other public buildings, where ownership of the assets cannot be transferred to the private partner.

-

The PPP-Purchaser-Model [(design)-build-own-operate-transfer] also features the private ownership of the assets during the contract term. At the end of the contract term, the assets are transferred back to the implementing public body. Risk allocation, life-cycle tasks and the structure of the payments are not specifically different from other PPP-Models in social infrastructure. The term purchaser refers to the fact that the private partner has to acquire the building ground. Therefore, the regular payments by the implementing public body include corresponding amounts. The PPP-Purchaser-Model is similar to usual real estate project developments.

-

The PPP-FM-Leasing-Model (design-build-lease-operate-transfer and/or maintain) is consistent with the PPP-Purchaser-Model. The main difference lies in the ownership of the assets. While the private partner owns the assets, the public body retains a call option to purchase the asset at the end of the contract term at a predefined price. In case that the public body does not make use his call option, the private partner remains the owner of the assets. Due to the design of this model, the private partner bears all of the ownership risks, including realization risks. Furthermore, the periodical remunerations by the public body do not cover the private partners’ investment costs. Compared to common real estate leasing models, inside the PPP-FM-Leasing-Model the private partner may also take more responsibility for the operation of the assets. In summary, the life-cycle tasks design and construction are not part of the contract between the private partner and the public body, but a prerequisite to conclude the main contract after the PPP-FM-Leasing-Model.

-

The PPP-Renting-Model (design-build-renovate-operate-transfer) is similar to common real estate renting, except for the fact that it features the operation of the assets by the private partner. The model assumes that the private partner owns the building ground, the assets and also designs, builds, finances and operates/maintains the assets. The PPP-Renting-Model is a PPP-FM-Leasing-Model without the public call option at the end of the contract term. Therefore, the periodical payments reflect common local rent levels and a premium for facility management services. In summary, the private partner will not be able to recover investment costs during the contract period, but by the means of utilization of the assets. Concluding, realization risks are fully borne by the private partner.

The following two models might be combined with the five models pointed out above. These two models might not be applied stand-alone:

-

The optional PPP-Concession-Model (build-operate-transfer) can be applied to promote user financing (e.g. arenas, indoor swimming pools or exhibition centers or roads and fresh water supply). The concession given to the private partner, entitles him the right to levy charges from users of the service provided. Consequently, the private partner receives no regular periodical payments from the public body. Therefore, the private partner bears market risks.

-

The optional PPP-Joint-Venture-Model features a common project company, of which the implementing public body and the private partner are joint shareholders. Rights and obligations of the partners are ruled inside the shareholder agreement in despite of a PPP-Contract. This makes it a so-called ‘horizontal’ partnership instead of a ‘vertical’ partnership in other PPP contracts. The model is well suited to urban development projects where the public body provides building grounds, determines development objectives and the private partner develops, designs, builds, finances, operates and markets the assets.

As pointed out above, the models applied in public real estate and road infrastructure are different. The following models are applied in road infrastructure:

-

A-Model

-

F-Model

-

Municipal-Roads-Models

The A-Model [(design)-build-operate-transfer] is a concession model in the German road sector. The designated projects have in common that existing stretches have to be replaced and/or widened. Hence, these projects are Brownfield developments. The private partner builds, operates, maintains and finances stretches on German highways. The underlying contracts have a term of 30 years after which the assets fall back to the public bodies. The devolution is determined to special conditions of the assets. In the A-Model, the private partner receives the revenues from the federal HGV-toll of the specific stretch. Because the toll is levied by a separate company (Toll Collect), the revenues are passed through to the VIFG, who distributes stretch-specific revenues to the operators of the A-Model-Projects. Depending on the specific project, the operator might receive initial funding from the federal budget, if the toll revenues do not cover incurring costs over the life cycle of the specific project. In contrary to F-Model projects, the private Partner is not entitled to levy tolls by himself (real toll). In conclusion, there is no link between A-Model-Projects and the Federal Road Private Funding Act (FStrPrivFinG). The benefits of the A-Models are in line with typical PPP targets such as faster delivery, life-cycle approach, budget relief and user finance (in part). After experiences made with the initial four A-Model projects, the framework was updated, focusing on remuneration mechanisms and now including availability payments.

The F-Model [(design)-build-operate-transfer] projects are based on the Federal Road Private Funding Act (FStrPrivFinG), since these models feature real toll levying by the operators. The F-Model-Projects are developed to design, build, operate and maintain crossings, such as bridges tunnels or mountain passes for a contract term of 30 years. The projects realized so far are entirely Greenfield projects that performed unsatisfying, as user financing in the German road sector is in desperate need for more acceptance. Unless the operator is entitled to levy toll from the users, he does not own the right to adjust tariffs. The tariffs can be adjusted upon requests to the responsible (toll ordinance) authorities. Analogous to the A-Model-Projects, the respective authorities can grant initial funding. The benefits of the F-Models are in line with typical PPP targets such as faster delivery, life-cycle approach, budget relief and user finance (in full).

Besides the A- and F-Model-Projects, there are several non-standardized initiatives for municipality roads. Realizing authorities are local municipalities and federal states opposing to the A- and F-Models that are realized by the federal states and the federal government. Basic characteristics of municipal roads models feature Brownfield characteristics with little demand for newly built assets and a strong focus on maintenance and sometimes operation. The models also feature availability payments, since the private operator or the local authority levies no toll. The benefits of the municipal road models are in line with typical PPP targets such as faster delivery, life-cycle approach and budget relief. Municipal roads models do not feature user finance and since they are focused on maintenance, they do not require high initial investments from the private partners. Realized projects so far own pilot project statuses.Footnote 15

6 German PPP Market

The German PPP market is dominated by strategic investors such as building corporations, respectively their investment-specific corporate divisions. Especially HOCHTIEF AG and Bilfinger Berger SE (as the largest national construction groups) compete with numerous foreign building corporations in the German PPP market. Competitors to HOCHTIEF AG and Bilfinger Berger SE are Austria-based STRABAG AG, Vinci S.A. from France and Royal BAM Group NV from the Netherlands that operate heavily active branches in Germany. On international level they also compete—among others—with France-based Eiffage SA, Colas SA and Egis SA as well as with Dura Vermeer Group NV from the Netherlands, Skanska AB from Sweden, Balfour Beatty plc. From the UK and Sacyr Vallehermoso SA from Spain. The common concern of these companies is focused on direct business, operative and financial interest of the projects.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, their equity investments are the means to an end in terms of the right to mandate their own construction branches to erect the physical assets of the projects. The same counts for SME’s those are active in the PPP-Market as well. The big difference is that SME’s are predominantly active in projects with forfeiting models and almost no need for equity investment. The corporations are focused on PPP-Projects that include project finance and seek for financial investors to take over equity investments partially. Active Germany-based SME-sized contractors in the PPP-Market are Goldbeck GmbH, Johann Bunte Bauunternehmung GmbH & Co. KG, Berger Holding GmbH, Otto Wulff Bauunternehmung GmbH & Co. KG, Theo Urbach GmbH & Co., Aug. Prien Bauunternehmung GmbH & Co. KG, Wiebe Holding GmbH & Co. KG, Bauunternehmen Gebrüder Echterhoff GmbH & Co. KG, Heitkamp BauHolding GmbH, A. Frauenrath Bauunternehmen GmbH, MBN Bau AG and Austria-based Alpine Bau GmbH and many more. Still, they predominantly invest in projects with forfeiting models or they are junior-investment-partners to building corporations in projects involving project finance.

Besides these strategic investors more and more institutional investors like e.g. assurance companies and pension funds show interest in investing in infrastructure by means of PPP. Against the background of the low level of interest rates and missing opportunities for lucrative investments corresponding to their requirements they seek for loopholes. The German Government seems to support the initiative by several coordinated efforts of the German Ministries of Finance (BMF), of Economic Affairs (BMWi) and of Transport (BMVI). A high level expert commission composed of leading representatives from companies and unions, central associations of the different economic sectors and science under the lead of Prof. Marcel Fratscher, President of Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW) has been invited by the Federal Minister for Economic Affairs Sigmar Gabriel in order to work with him on a new investment strategy for Germany in general and for Germanys infrastructure in particular.

7 Deal Flow

Since 2003, the German market for PPP-Projects with a full life cycle approach has been growing constantly. Investments are focused on projects in the public real estate sector executed on municipal level, while only a few projects were realized on federal level. Regarding the specific sector, these investments are heavily concentrated on schools, also because bundled projects were realized in this sector. Major experiences in the German PPP-market were made in the public real estate sector. Inside the sector, about 200 projects with total investments of about 5.7 billion euros were realized since 2002.Footnote 17 The major stake of these projects is already in operation and further projects are currently in tendering or in preparation. Considering the economic crisis in 2007, the deal flow in the German PPP sector remained intact, notwithstanding that the general development has abated since then. However, the time since the economic crisis showed that PPPs in the real estate sector have become an established procurement method among total public procurement. Table 1 shows that the past project pipeline had a total estimated investment value of approximately 5.7 billion euros.

Current estimations of the project pipeline in the public real estate sector result in approx. 100 projects that are either tendering, under preparation or under assessment.Footnote 18 Table 2 shows the distribution of PPP-Projects among the different sectors in the German public real estate sector. The total number of awarded projects holds a remarkably high proportion of school and educational projects.

As already noted above, the road infrastructure sector is somewhat different from the real estate sector. Investments concentrated on federal level instead of federal state and municipal level. In addition, the continuity of projects in tendering and announced projects strengthen the role on federal procurement in the road infrastructure sector. Characteristics of these projects are a higher investment volume and the low number of projects, when compared to the real estate sector.

While road infrastructure projects initially took off with the so called F-Model projects in 2002, this type of projects has completely vanished today. The small number of F-Model-Projects and their poor performance were bound to the low acceptance of user financing and too optimistic traffic forecasts. Furthermore, these models did not feature an optimal risk allocation, since major construction risks and market risks remained with the private partner. Initially, the realized F-Model-Projects were pressed into the scheme, as no suitable projects were available at a point of time where PPP-Projects in road infrastructure should be realized. In conclusion, the political support of these projects was lacking. Finally, realizing authorities were open for renegotiations of the original contract, so that bankruptcies were avoided. The adapted means were extensions of the contract terms up to 20 years, totaling in contract terms of up to 50 years.

Compared to the F-Model-Projects, the A-Model-Projects have proven to be successful inside the market. Developments reaching back to 2002, the A-Model-Projects are crucially linked to the German HGV-Toll and the separate toll collecting company Toll Collect. Since A-Model-Projects also feature partial market risks, the overall risk allocation and general package seems more attractive and thoroughly designed than F-Model-Projects. The seven projects that have been tendered so far were soaked up by the market and involved big interest from investors and contractors outside of Germany. The projects currently in tendering and in preparation feature re-designed contracts with higher levels of standardization and fierce competition for the projects. The average investment costs for one A-Model-Project amounts to approx. 500 million euros. Hence, international infrastructure investors seek for ways to invest into these projects. Past F-Model and A-Model-Projects in the German road infrastructure sector are included in Table 3.

In consideration of the financial market crisis from 2007 and induced developments, the German PPP market could not match up with expectations from the construction industry and financial investors. Some of the developments in the course of the financial market crisis have affected the German PPP market. Firstly, lower tax receipts impaired the financial situation of German municipalities and secondly, the impact of the federal stimulus packages, which promoted conventional procurement, ran out in early/mid 2011. In these years the urge, especially for municipal investments was relieved through other means than PPPs. This led to postponed or abandoned projects, as the private sector was experiencing problems to arrange debt financing for projects in the stage of implementation.

The pipeline for projects under design or preparation and with tender procedures on the way currently holds another six projects to hit the market in 2015 and beyond. Table 4 provides an overview to the planned PPP-Projects in the German road infrastructure sector on federal level:

8 Outlook

After the federal election in 2005, the 16th German government referred to PPP in its coalition agreement as an alternative procurement method of increasing importance that was expected to be applied to up to 15 % of the overall public procurement. The future deal flow remained hard to anticipate, since most of the projects in numbers are executed on municipal level in the public real estate sector. Currently not more than 3 % on municipal level and 5 % on federal and federal state level of the public procurement in public construction has been realized by a PPP approach.Footnote 19 After the federal election in 2009, the 17th German government did not take up such a clear position in favor of PPPs inside their initial government declaration. It is rather that opponents to PPP models receive more attention in the media. Then, temporarily developments caused by the growing federal tax earnings are actually supporting the arguments of the PPP opponents. Their criticism leaves out the highly visible benefits of implemented PPP-Projects and achieved standardizations. Still, restrictions of public budgets on any administration level are growing. Because the positive development of public revenues did not change structures, the investment backlog in any infrastructure sector is still growing. Future concerns will definitely become bridges of federal and federal state roads. In conclusion, the pressure to apply alternative methods of public procurement, including PPP models, will grow. This is due to the consideration of the decreasing impacts of the financial market crisis and due to keener supervision of public debt limits, especially in the light of the Euro-crisis.

Notes

- 1.

The public agent makes use of thorough cost-benefit-analyses to proof value-for-money. Tytko (1999), p. 32.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

Literature reviews imply that long before the financial market crisis it has been argued that the advantage of the leverage-effect depends very much on the current market conditions. Financial structures based on the leverage-effect crucially require non-rising interest rates. Newell and Peng (2008), p. 23; Blanc-Brude and Strange (2007), p. 2; Probitas Partners (2007), p. 9 and Tytko (1999), p. 8.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

The leeway results from the SPC’s property rights and volume-related risks remained with the SPC. The price of debt for the SPC is lower, if she bears no risks. Leland (1998), p. 1228.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

PD (2014), pp. 6 and 19.

- 11.

Hausmann and Rudolph (2008), p. 156.

- 12.

§2, VIFGG.

- 13.

The PPP-Contracting Model, which used to belong of the group of eligible models has vanished in recent years due to lacking demand. It was designed for special projects that do not feature the construction of buildings, but the design, installation, optimization, operation and maintenance as well as financing of technical facility equipment (HVAC). The contract term was limited between 5 and 15 years, depending on the life cycles of technical facility equipment.

- 14.

PwC et al. (2003).

- 15.

Korn (2008), pp. 61–62.

- 16.

Tytko (1999), p. 23 and p.47.

- 17.

PD (2014), p. 5.

- 18.

PD (2014), p. 6.

- 19.

PD (2014), p. 9.

Bibliography

Alfen Consult GmbH (2010) (German) Experience with PPP-Projects in the roads sector. Lecture at the City of Jelgava, Latvia, 26–27 Apr 2010

Blanc-Brude F, Strange R (2007) Risk pricing and the cost of debt in public-private partnerships: evidence from the syndicated loan market. Kings’s College London, Department of Management, Research Paper 45, March 2007

Blecken U, Meinen H (2007) Quantitative ökonomische Modelle für PPP- und BOT-Projekte. Issue 1 of the journal series from the chair of Construction economics published by Prof. Dr.-Ing. Mike Gralla. Werner-Verlag 2007, Dortmund, Germany

Braune GD (2006) Finanzierung. In: Littwin F, Schöne F-J (eds) Public Private Partnership im öffentlichen Hochbau, 1st edn. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany, pp 263–319

Clifton C, Duffield CF (2006) Improved PFI/PPP service outcomes through the integration of alliance principles. Int J Proj Manag 24(2006):573–586

Devapriya KAK (2006) Governance issues in financing of public-private partnership organisations in network infrastructure industries. Int J Proj Manag 24(2006):557–565

Ertl M (2004) Aktives Cashflow-Management: Liquiditätssicherung durch wertorientierte Unternehmensführung und effiziente Innenfinanzierung, 1st edn. Verlag Franz Vahlen, Munich, Germany

FPK (2015) Föderales PPP Kompetenznetzwerk, Mitgliederübersicht. http://www.ppp.niedersachsen.de/portal/live.php?navigation_id=12868&article_id=55867&_psmand=49. Accessed 16 May 2015

Grout PA (1997) The economics of the private finance initiative. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 13(4):53–66, Published by Oxford University Press

Hausmann L, Rudolph B (2008) Partnerschaften Deutschland launched to counsel the public sector and further promote PPP in Germany? Eur Public Private Partnership Law Rev (EPPPL) 3(3):156–159, Published by Lexxion Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin, Germany

Henschel-Bätz M (2005) Eigenkapitalbeschaffung aus Sicht mittelständischer Bauunternehmen. Workshop documentation: “Strategien der Eigenkapitalbeschaffung für PPP-Projekte” from September 22nd 2005 in Berlin; published by Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie e.V., Berlin, Germany 2006

Hopfe J, Napp H-G, BergmannS (2008) Kapitel 4—Finanzierung. In: PPP-Handbuch: Leitfaden für Öffentlich-Private-Partnerschaften; published by Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS) and Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband (DSGV), April 2008, Berlin, Germany, pp. 130–175

Korn M (2008) PPP in the sector of road infrastructure on the county and municipal level in Germany: a story for the future? Eur Public Private Partnership Law Rev (EPPPL) 3(2):58–63, Published by Lexxion Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin, Germany

Leland HE (1998) Agency costs, risk management, and capital structure. J Financ 53(4):1213–1243, Published by Blackwell Publishing for the American Finance Association, August

Littwin F, Weihnacht A, Michelmann J (2003) Public Private Partnership im Hochbau. Organisationsmodelle. Public Private Partnership-Initiative. Published by Public Private Partnership-Initiative NRW, 12th August 2003, Düsseldorf, Germany

Müller R, Turner JR (2005) The impact of principal-agent relationship and contract type on communication between project owner and manager. Int J Proj Manag 23(2005):398–403

Newell G, Peng HW (2008) The role of U.S. infrastructure in investment portfolios. J Real Estate Portfolio Manag 14(1):21–33, Published by American Real Estate Society

PD (2014) Öffentlich-Private Partnerschaften in Deutschland, 2014. Berlin, Germany, 31 Dec 2014, http://www.partnerschaften-deutschland.de/uploads/media/150225_OePP-in-Deutschland_Jahresbericht_PPP-Projektdatenbank_2014_01.pdf, Accessed 16 May 2015

Pfnür A, Schetter C, Schöbener H (2008) Risikomanagement bei Public Private Partnerships. Experts Report by order of Initiative Finanzstandort Deutschland (IFD), Darmstadt, Germany, 29 Aug 2008

Probitas Partners (2007). Investing in infrastructure funds. Published by Probitas Partners, September 2007

PwC, FBD, VBD, BUW, CC (2003) PPP im öffentlichen Hochbau; Experts Report on PPP in Public Real Estate published by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (FBD), Beratungsgesellschaft für Behörden GmbH (VBD), Bauhaus-Universität Weimar (BUW) and Creativ Concept (CC), 2003

Schöne F-J (2006) Ausgewählte Rechtsfragen/Vertragsrechtliche Aspekte. In: Littwin F, Schöne F-J (eds) Public Private Partnership im öffentlichen Hochbau, 1st edn. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany, pp 98–118

Sester P, Bunsen C (2005) Vertragliche Grundlagen—Finanzierungsverträge. In: Weber M, Schäfer M, Hausmann FL (eds) Praxishandbuch public private partnership. Verlag C.H. Beck, Munich, Germany, pp 436–497

HOCHTIEF PPP Solutions (2014) HOCHTIEF-Konsortium erreicht Financial Close für A7 in Schleswig-Holstein und HH. http://www.hochtief.de/hochtief/pdfservice/9636. Accessed 19 May 2015

Spackman M (2002) Public-private partnerships: lessons from the British approach. Econ Syst 26(2002):283–301

Tytko D (1999) Grundlagen der Projektfinanzierung, 1st edn. Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany

VIFG (2008a) Das F-Modell Warnowtunnel. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/kompetenzen/f-modell/2008-12_Projektsteckbrief_F-Modell_Warnowtunnel.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2008b) Das F-Modell Warnowtunnel. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/kompetenzen/f-modell/2008-12_Projektsteckbrief_F-Modell_Herrentunnel.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012a) Das A-Modell A8. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A8.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012b) Das A-Modell A4. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A4.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012c) Das A-Modell A1. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A1.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012d) Das A-Modell A5. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A5.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012e) Das A-Modell A8 II. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A8_II.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2012f) Das Verfügbarkeitsmodell A9. http://www.vifg.de/_downloads/projekte/a-modell/2012-10_Projektsteckbrief_A-Modell_A9.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFG (2015) Homepage of the VIFG. http://www.vifg.de/en/projects/a-model/index.php. Accessed 19 May 2015

VIFGG (2006) Gesetz zur Errichtung einer Verkehrsinfrastrukturfinanzierungsgesellschaft zur Finanzierung von Bundesverkehrswegen (Verkehrsinfrastrukturfinanzierungsgesellschaftsgesetz—VIFGG). Issued on June 28th 2003 (BGBl. I S. 1050), updated by article 283 of the Verordnung from October 31st 2006 (BGBl. I S. 2407)

Weber B, Alfen HW (2009) Infrastrukturinvestitionen—Projektfinanzierung und PPP, 2nd edn. Bank-Verlag Köln, Cologne, Germany

Weber M, Moß O, Schwichow H (2004) Public Private Partnership im Hochbau. Finanzierungsleitfaden. Public Private Partnership-Initiative, published by Public Private Partnership-Initiative NRW, Düsseldorf, Germany, October 2004

Weber B, Alfen HW, Maser S (2006) Infrastrukturinvestitionen—Projektfinanzierung und PPP, 1st edn. Bank-Verlag Köln, Cologne, Germany

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alfen, H.W., Barckhahn, S. (2017). PPP and Infrastructure. In: Just, T., Maennig, W. (eds) Understanding German Real Estate Markets. Management for Professionals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32031-1_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32031-1_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-32030-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-32031-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)