Abstract

In the United Kingdom, the design and process of university assessment, particularly at the undergraduate level, has come under intense public scrutiny following the implementation of policy aimed at improving educational standards. The introduction of student fees and national satisfaction surveys has promoted competition between institutions for student numbers with ‘assessment and feedback’ being considered a key indicator of student engagement and overall satisfaction with their experience. This has put assessment at the centre of learning and teaching strategies and innovation. Performance assessment in professional education, particularly in medicine and nursing, is primarily focused on ensuring fitness to practice and has more well defined performance outcomes than more traditional science and social science disciplines. Healthcare students are required to keep a portfolio of knowledge and skills supported with competence assessments. Other disciplines in higher education are now required to keep student portfolios of transferable skills as part of demonstrating ‘employability’. Undertaking formative feedback on student performance, particularly in the work place, is becoming more challenging. Increasingly in the multi-disciplinary and high-service demand environments of the National Health Service, clinical care priorities leave little time for educational activities. In response, profession educators are re-conceptualising forms of feedback and assessment in these contexts. Examine ways in which assessment strategies and methods need to evolve in clinical and higher education to respond to policy, professional body and student expectations, and the implications of this for faculty development in both institutional and work-based contexts. Drawing upon national and institutional data, we have identified key assessment issues, notably the importance and challenge of receiving timely and purposeful feedback. We also offer suggestions for strategic and innovative solutions, for example, advantages of creating curriculum as opportunities for student learning, but viewing curriculum as a set of system-wide development processes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

9.1 The Higher Education Policy Context

In the United Kingdom (UK), the design and process of university assessment, particularly at the undergraduate level, has come under intense public scrutiny following the implementation of policy aimed at improving educational standards. A series of Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE) national initiatives to improve the quality and status of learning and teaching simply disappointed the sponsor. The speed and scale of change was slow and patchy. Encouraging the sector to move in particular directions proved a more complex negotiation than the voluntary engagement of teaching enthusiasts. What was happening? Why was the task of improving learning and teaching too complex? Were the resources insufficient or ineffectively deployed? Perhaps all of these. In addition, there was an ideological tension that was to influence how higher education was to evolve.

Underpinning concerns about the quality of higher education lay fundamental shifts in thinking about the role and purpose of higher education. These involve contested views about what learning, teaching and assessment could and should involve. The international and national dimensions of higher education policy provide a significant context for understanding the values, ideologies and aims within the assessment debate.

In the late 1990s and early twenty-first century, there was a global focus on the need for a knowledge-based society (Garnham 2002). Fears about economies failing were central to debates about the educational implications for developing learners to meet the needs of a knowledge-based society. A prevailing view argued that technological innovation, the improved speed and access of communications, and the growth of global markets required a new kind of workforce. That workforce was characterised by workers who could quickly re-skill, acquire new knowledge and move into changing roles.

Preparing students to meet the challenge of becoming part of such a workforce requires an ability to adapt to rapid and frequent change. This is not a new challenge for education in the professions tasked with preparing practitioners for the complex and dynamic environments of health-care settings. The 2013 the final report of an independent review of postgraduate medical training called ‘The Future Shape of Training’ identifies similar workforce needs with a particular emphasis on flexibility to undertake new roles.

In professional and higher education, the intensified focus on workforce planning, and employability has pedagogic implications. Dr. Nick Hammond, senior adviser at the Higher Education Academy in the UK, describes these below:

The changing world to be faced by today’s students will demand unprecedented skills of intellectual flexibility, analysis and enquiry. Teaching students to be enquiring or research based in their approach is central to the hard-nosed skills required of the future graduate workforce (Hammond 2007, p. 3).

There was more at stake than shifting pedagogic approaches. The purpose and functioning of universities, the social contract between higher education and the state, was being re-drawn. Responsibilities of universities to contribute to the well-being of society were being reconsidered. Universities were rethinking access. This was affecting what universities did, for whom, and how. This had serious implications for individual and institutional identities (McKee 2012).

UK institutions have created employability opportunities and associated support mechanisms for their students. Some have gone further and oriented themselves firmly toward an employability agenda. Just as other institutions use their research pedigree to distinguish themselves, some universities are using their employability focus to create an institutional identity that distinguishes themselves from their competitors. [For example: Coventry University (www.coventry.ac.uk), the University of Hertfordshire (www.herts.ac.uk), and The University of Plymouth (www.plymouth.ac.uk).]

UK policy changes affected both universities and students. The funding of universities and their degrees was at stake. The government paid student fees directly to universities and provided students with grants to cover living costs while they studied. This policy was transformed in stages. In 1990, The Education (Student Loans) Act was passed in the UK which meant students now received and repaid loans towards their maintenance while studying.

Student loans were part of a series of UK policy initiatives to contain public spending on higher education. The shift from giving students grants to providing student loans occurred in 1997 with the Dearing Report. Since then, the cost of university study in England has trebled from an average of £3000 per student per year to a capped figure of £9000 per student per year. This increase in fees created two concerns within the sector. The first was that access, especially for low-income families, would be compromised. The second was that student expectations would rise.

Parallel with changes in resourcing levels and funding structures were a series of UK Government initiatives to improve the quality of learning and teaching. These involved a shift from a non-intervention approach that highly valued the autonomy of universities to categorical funding to generate development in broad areas, such as enterprise. One example was the creation of a National Teaching Fellowship Scheme. This award helped celebrate individual teaching excellence. Another initiative, Funds for the Development of Teaching and Learning, offered resources to develop good teaching practice in priority areas, such as inter-professional education.

Other initiatives sought to enhance the structures supporting teaching. Twenty four ‘Subject Centres’ of broadly grouped discipline areas were created to focus work within disciplines. Subject Centres were hosted by institutions, distributed across the UK, with oversight and control by the UK Higher Education Academy. The final initiative was a 315 million pound sterling five-year programme to create institutionally based Centres for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL). Seventy three CETLs were funded and tasked with having impact at an institution, and across a sector. Some CETLs were focused on disciplines (Centre for Excellence in Mathematics and statistics support), some on areas of activity (Assessment for Learning CETL), and others on institutional imperatives (e.g. The Blended Learning Unit).

However, few of these initiatives have been sustained. Improving the quality of learning, teaching, and assessment is a complex activity requiring more time, resources, and widespread collaboration.

The UK National Student Survey (NSS) has been influential in focusing institutional development, particularly in areas of assessment and feedback. Launched in 2005, all undergraduate students complete it in their final year. NSS is a retrospective evaluation by students of their experience in eight categories:

-

Teaching On My Course,

-

Assessment and Feedback,

-

Academic Support,

-

Organisation and Management,

-

Learning Resources,

-

Personal Development,

-

Overall Satisfaction, and

-

Students’ Union.

Sponsors of the survey, The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), intended that information gathered would give students a voice in the quality of their learning and teaching experience. The information is publically shared. Prospective students and their parents and families make choices for particular degree programmes and universities.

The survey’s validity, how it respects the complexity of the student experience, and its reliability across time, has been hotly debated. Critics argue that student engagement has been neglected. Developers of the survey want to better understand learner’s experience away from the current consumer orientation toward a student engagement approach. Students are not merely passive learners but have a role and responsibility in their own learning journey. For example, the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSEE) used in the United States is an engagement rather a satisfaction-oriented survey. Despite its focus, the annual production of league tables of student satisfaction has made the NSS both influential and consequential. Across the sector, student satisfaction in the Assessment and Feedback category tends to be consistently low. Though some universities have made significant improvements, assessment and feedback is problematic across much of the sector. Though NSS might be helpful in identifying an area of concern, it offers scant information and little if any insight into the nature of the challenge.

The Assessment Standards Knowledge Exchange (ASKe), one of the Centres for Excellence in Learning and Teaching, convened an international group of academics and assessment experts to probe the complexity of Assessment and Feedback to help support change across disciplines. In 2007, a convened group (Western Manor Group of 30 participants) produced Assessment: A Manifesto for Change. The Manifesto focuses on assessment standards (one of the tenants is Standards Without Standardisation) and is comprised of six separate-yet-linked tenets. These are:

-

1.

The debate on standards needs to focus on how high standards of learning can be achieved through assessment. This requires a greater emphasis on assessment for learning rather than assessment of learning.

-

2.

When it comes to the assessment of learning, we need to move beyond systems focused on marks and grades towards the valid assessment of the achievement of intended programme outcomes.

-

3.

Limits to the extent that standards can be articulated explicitly must be recognised since ever more detailed specificity and striving for reliability, all too frequently, diminish the learning experience and threaten its validity. There are important benefits of higher education which are not amenable either to the precise specification of standards or to objective assessment.

-

4.

Assessment standards are socially constructed so there must be a greater emphasis on assessment and feedback processes that actively engage both staff and students in dialogue about standards. It is when learners share an understanding of academic and professional standards in an atmosphere of mutual trust that learning works best.

-

5.

Active engagement with assessment standards needs to be an integral and seamless part of course design and the learning process in order to allow students to develop their own, internalised, conceptions of standards and monitor and supervise their own learning.

-

6.

Assessment is largely dependent upon professional judgement and confidence in such judgement requires the establishment of appropriate forums for the development and sharing of standards within and between disciplinary and professional communities.

In 2009, ASKe convened another forum (Osney Grange Group) to identify and examine key issues in feedback and suggest possible resolutions. Feedback: An Agenda for Change was a significant outcome from the Group. This Agenda sets forth “the intention of tackling underpinning theoretical and practice issues in feedback and creating a cross-disciplinary framework to inform improvement and development” (see Merry et al. 2013).

The five clauses of Feedback: An Agenda for Change are:

-

1.

High-level and complex learning is best developed when feedback is seen as a relational process that takes place over time, is dialogic, and is integral to learning and teaching.

-

2.

Valuable and effective feedback can come from varied sources, but students must learn to evaluate their own work or they will be dependent upon others to do so. Self and peer review are essential graduate attributes.

-

3.

There needs to be a fundamental review of policy and practice to move the focus on feedback from product to process.

-

4.

Reconceptualising the role and purpose of feedback is only possible when stakeholders at all levels in higher education take responsibility for bringing about integrated change.

-

5.

The Agenda for Change calls on all stakeholders to bring about necessary changes in policy and practice (Price et al. 2013).

What are the implications of this policy context for institutions? We address this question by examining a Feedback and Assessment evaluated initiative within ‘King’s College London’.

9.2 King’s College London: An UK Higher Education Institution

King’s College London is a large UK university located in the heart of London, England. Approximately 25,000 students study at King’s and are taught in one of eight academic Faculty’s. The University has a significant emphasis on research and is a member of the UK elite Russell Group. As such, any significant endeavours need to be cognisant of the research-intensive context. Although King’s is highly ranked in international university league table some student satisfaction league tables highlight less favourable ranking. Additional information relating to the institutional context and history of King’s College London can be found in Appendix.

The governance of education at King’s is highlighted in Fig. 9.1. There is a clear connection from academic programmes, departments, to academic Faculties, to an overseeing College Education Committee. Such connections ensure a university connectedness and allow the educational values and strategies to flow throughout the institution. The responsibility for ensuring faculty-based academic standards and driving continual educational improvements is devolved to a dedicated faculty-based education lead. The College Education Committee, of which each of the Faculty education leads are members, is chaired by the University’s lead for education [Vice Principal (Education)].

The University has an Education Strategy which sets out the strategic imperatives and presently sets out, amount other things, the importance of technology-enhanced learning, assessment and feedback.

9.3 A University Initiative

Prevailing and often reiterated NSS concerns about assessment and feedback, and our understanding of the importance of assessment for student learning, has led to a cross-University, two year, assessment and feedback project.

9.3.1 Guiding Principles

-

Ensure that teaching, learning outcomes, and assessment are constructively aligned (Biggs 2003 ).

-

Create an institutional imperative while allowing scope for local-relevance.

-

Engender responsibility for enhancement of assessment, as appropriate, with the institution, collaborations, individual staff members, and students.

-

Use appreciative inquiry approaches rather than deficit models of engagement.

-

Consider embedding principles of assessment for learning in University policies and procedures.

-

See students as active partners and contributors to all phases of the project.

-

Build on and learn from previous centrally led and locally led faculty-based assessment and feedback initiatives.

-

Be inclusive and develop assessment leaders across the University.

-

Build and cascade capacity in assessment expertise.

-

Use and develop governance of education, including reporting and action planning around assessment. Ensure that associated systems, workflows and regulations help assessment endeavours. Ensure that creativity flourishes in assessment.

-

Create ways of working with clear communication channels and lines of responsibility and ownership.

-

Align to the mission and strategy of the University.

-

Become research-informed and evaluative in approach.

-

Enhance educational effectiveness and resource efficiency of assessment activities.

9.3.2 Project Governance

The importance of this work is demonstrated by the strategic oversight from the University’s Vice Principal (Education).

There was a significant intent in the project to become collaborative, collegiate, and support the development of assessment literacies for both staff and students. The project sought to secure a long-lasting and positive impact rather than promote short-term responses and so called quick-wins. To assist with this objective, the project established four responsibility areas:

-

Institutional responsibility: systems and processes assure academic quality without stifling creativity in the assessment domain.

-

Team responsibility: ensuring collective responsibility to an assessment agenda within schools, departments and teams.

-

Individual responsibility: ensuring that staff who engage students understand students’ personal importance and the impact of their assessment activity.

-

Student responsibility: Developing agency and assessment literacy.

In the first year, the central project team was working with programme teams as pilots. Pilot programmes were drawn from across the University:

-

Bachelor of Laws (LLB Undergraduate programme).

-

Pre-Registration Nursing (BSc Undergraduate programme).

-

Management (BSc) (Undergraduate programme).

-

English (BA) (Undergraduate programme).

-

MSc Mental Health (Postgraduate programme).

-

MSc Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Postgraduate programme).

-

MSc Genes and Gene Therapy (Postgraduate programme).

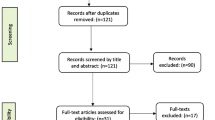

The programmes were identified an Assessment Leader where such a role does not already exist, in order to provide leadership within the Faculty and a single point of contact. Enthusiasm to engage at the early stages is important, as these ‘early adopters’ will become ‘champions’ within each Faculty and, working with the Assessment Leaders, will help bring about a process of wider-development and support a response to any locally prevailing assessment concerns. The project structure is outlined in Fig. 9.2. The targeted areas were supported for inter-faculty diffusion of experience and development.

In all responsibility areas, the project’s organisation refers to other relevant parts of the University. Overarching the ways of working is an appreciative inquiry approach. It sets out an institutional direction whilst allowing Programme teams to account for local programme and subject specialties. Russell et al. (2013) have shown repeatedly that an appreciative inquiry approach is more helpful because it illuminates existing success rather than highlights deficits. For those readers looking for challenges to resolve, programme teams often highlight issues or concerns even when a discussion focuses on things going well. It takes a strong and observant leader to bring the group back to focusing on strengths.

The broad activity in the pilot includes:

-

Establish the current status. Visually map the assessment landscape of the pilot programmes. The mapping activity includes:

-

timeline of assessment (on the modules of the degree programme),

-

stakes of the assessment (low, medium, or high in relation to marks),

-

nature of the assessment activity (essay, examination, presentation, etc.) and,

-

links between any assessment tasks (links within and across the modules).

-

-

Establish the rationale for the current assessment strategy.

-

Assessment redesign and making more use of existing effective and efficient assessment.

-

Evaluation and diffusion.

-

Operate in a continuous cycle of generative activity with continuous evaluation to generate new ideas and involvement by teams and faculty.

For future work, and to build opportunities for growing and sustaining the impact,

-

Plan for and create an assessment review and redesign process to enable other programme teams to undertake assessment reviews and redesign.

A sample assessment landscape is shown in Fig. 9.3. The circles indicate the assessment activity (colour coded and scaled to indicate the weighting of the task), whereas the lines represent the learning-oriented links between the different assessment tasks. The recycling process is also indicated.

9.3.3 Emerging Findings

There are significant strengths in some of the assessment designs as well as opportunities to reconsider such assessment designs. Some specific and immediate emerging findings include:

-

An interest in illuminating assessment activity at the programme level rather than at the module level,

-

An emphasis on the high stakes end of process examinations,

-

An emphasis on essays and examinations that are not administered in public,

-

Challenges of creating an educative assessment experience as class size increases, and

-

Challenges around consistency of marking.

Emerging findings show that faculty members and students need to become more confident and comfortable with assessment literacies. Two additional resources are being produced (see Fig. 9.4). Essentially, separate support guides that provide research-informed evidence to assist busy students and faculty members. The team intends such resources, not to assist faculty members to become assessment researchers, but rather to offer informed advice in relation to the need, design, development, implementation and evaluation of their assessment endeavours.

9.4 An Illustrative Case Study: Strategic Development of Collaborative Assessment Practices in Nurse Education

The Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery at King’s College London undertook a number of curriculum, assessment, and staff development initiatives. Their intention was to sharpen the focus on students’ educational experiences and engage in supported faculty reflection and development. What follows is an overview of assessment initiatives and an illustrative case study of a faculty-wide response to some of the assessment challenges. The work is centred on a collaborative approach to designing and utilising marking rubrics to improve both teaching and learning.

9.4.1 The Challenge

As mentioned, the NSS and other student evaluations suggested improvements in assessment, marking, and feedback were necessary. The King’s Assessment and Feedback Project afforded a timely, practical, and strategic opportunity to work with university partners to cohere our own evaluation and develop our own assessment practices.

The pre-registration BSc (Hons) Nursing programme, the largest undergraduate degree programme in the Faculty, was chosen as a pilot.

Additional data was gathered and analysed to establish and confirm the nature of some of the assessment challenges. Essentially, an audit exploring the quality of feedback and its compliance with procedures and alignment with good practice (Jackson and Barriball 2013) was undertaken. This audit helped clarify areas that required further guidance, support, and reiteration. In parallel, student focus groups examined their experiences of assessment processes and how feedback supported their learning. Faculty focus groups examined their experiences of the assessment process. From audit and focus group data, key issues clustered in three areas: Consistency, Transparency and Engagement:

-

Consistency

-

Disparity of grades between markers.

-

Variability and incongruence of feedback provided.

-

-

Transparency

-

A lack of shared understanding of the criteria within and across module teams.

-

Variability to the process brought about by non-faculty markers (clinical fellows).

-

University assessment criteria were too generic and did not fully reflect variation across the levels or between grade bands effectively or accurately (For example: level 4 criteria not substantially different from level 6 and a C grade not clearly different from a B grade).

-

-

Engagement

-

Ineffective communication of marking criteria to students.

-

Little or now use of the criteria and guidelines as a means of improving student work.

-

A need for students to take greater control of their learning.

-

These findings highlighted a need to:

-

Share good practice in assessment and feedback;

-

Support staff in developing educationally effective assessment and feedback;

-

Engender more collegiality in relation to teaching, learning and assessment;

-

Engage students more fully in the design, implementation and evaluation of learning and assessment practices.

9.4.2 The Response

The findings of the audit were used to inform improved assessment practices. One of these strategic activities was to introduce ‘module-specific’ marking rubrics to replace the generic university marking criteria. Given that lack of transparency and consistency of marking were key issues, it was decided that a bespoke rubric for each module would be more helpful to both staff and students.

A rubric is ‘a grid of assessment criteria describing different levels of performance associated with clear grades’ (Reddy and Andrade 2010, p. 435). It can be used for marking assignments, class participation, or overall grades. Research suggests that a module-specific rubric has major advantages. It provides a clear relationship between learning outcomes, learning activities and assessment (Hyland et al. 2006). The objectives of this project were to explore:

-

The value in using marking [grading] rubrics.

-

Evaluate student learning and assessment experiences.

-

Establish the ‘active ingredients’ of embedding consistency, transparency and engagement into our assessment and feedback processes to improve and enhance nurse education.

An evaluation matrix was constructed to review the outcomes of the work (see Table 9.1).

A series of workshops were developed and run on best practice in assessment. They included, assessing professional and clinical competence, creating assessment rubrics, and developing collaborative enhancement practices.

Four pilot modules were selected for the rubrics created. Two undergraduate pre-registration modules and two post-registration modules, using the DECIDE model (Russell-Westhead 2014). Essentially, the DECIDE model is a structured approach to the design, implementation and evaluation of a rubric (see Fig. 9.5).

-

Design

The module teams, and some students, met to decide how to develop rubrics that clearly linked to learning. Establish and make Explicit the key aims and outcomes of the assessment.

-

Create

The rubric was created by the team using a template based upon the University’s generic marking criteria. It made explicit professional competences and application of knowledge to nursing practice (evidence-based practice) not reflected in the institutional mark scheme. Rubric descriptors became quick marks on TurnItIn. This used the language of the assessment guidelines and reflected the aims and outcomes explicitly at each level.

-

Implement

The rubrics were used in various assessment contexts which are briefly introduced below:

9.4.3 Module 1—Self-Assessment

-

Neonatal Care (Level 5 Module on the Midwifery BSc Programme)

All students were invited to bring their full first draft assignment to a writing workshop after the last session of the module. They were given the marking criteria (the assessment rubric), the assessment task and a grading sheet and asked to critically appraise their own work as if it were another student’s work. They were to underline the comments in the rubric, which they felt best related to the essay and then provide a mark and feedback based on the assessment they had made. They then were asked to use the feedback to consider how they then could improve their work.

9.4.4 Module 2—Peer Assessment

-

Qualitative Research Methods (Level 7 Master’s module)

The approach was similar to the self-assessment activity of Module 1, but this time the submissions were peer reviewed. Students were given another student’s work to mark with the rubric, task and grade sheet. They were given 30 min to mark the work, assign a grade and write some developmental feedback. The tutor and researcher then monitored the student activity to ensure that everyone was engaging with the task correctly and fairly. The students were subsequently asked to discuss and justify their marking and comments to the person sitting next to them, which emulated the moderation process. This provided an opportunity to learn from other students’ experience.

9.4.5 Module 3—Tutor Led Assessment

-

Research Project on all Undergraduate Programmes (level 6 pre-registration)

This activity used a number of exemplar assignments from the previous year in each of the grade bands. These exemplar assessments were assigned to groups of three students and they were to mark the assignment as if they were the second marker using the rubric and guidelines and provide feedback. They then discussed their marking decisions as a group to compare their marks and comments. A group discussion followed as to what made a good and less favourable assignment. The tutor provided group feedback and support in how to improve using meta-cognition to tackle that assignment.

The students were then encouraged to apply the same approach with their own work prior to submission of their assessment. Their individual project supervisors/tutors supported the process but it was not compulsory to use this approach.

9.4.6 Module 4—360 Review

-

Leading and Managing Care (Level 6 post-registration module)

It was decided by the module lead that the design of an assessment rubric provided an opportunity to completely rethink both the assessment task and the approach to teaching and learning throughout the module. There were a number of formative tasks throughout the course, such as presentations, critical evaluations of reports, writing strategies and observing work practice and being observed in their clinical role. These tasks were either self-assessed (reflection), peer-assessed (critical evaluation), or tutor (or work colleague) assessed (critical judgment). The purpose of doing so was that the participant could see their work from multiple perspectives to offer several opportunities to learn from others. With support and facilitation the summative task and the rubric were designed by the entire module team (7 lecturers) along with a small group (n = 4) of ‘consultant students’ who self-selected to get involved. They collaboratively decided upon both the assessment task and the criteria for grading the assignment (Fig. 9.6).

Determine the Appropriateness of the Criteria—the rubric was evaluated by the staff as to the value, usability, and transparency of the criteria and where necessary modifications made and finally.

9.4.7 Evaluation

A pragmatic qualitative approach (Creswell 2007) was adopted to describe student and staff views and experiences of the rubric project. All students completed a standard module survey (n = 126) with an additional question about the use of the rubrics and associated class activities. In addition, student focus group interviews were carried out at the end of each of the pilot module and six semi-structured one to one interviews. The audio from the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. The survey data, transcriptions and interview notes were uploaded into QSR’s NVivo 9 qualitative data analysis software.

Additional triangulation involved examination of the module handbook and feedback sheets. The purpose of the document review was to address the overarching project impact measures. In particular, the measures are around consistency and transparency.

The survey data, focus group and one to one interviews were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) and constant comparison techniques (Rapley 2010).

The data from students and staff were analysed and responses for each group were compared within each theme to identify any similarities and differences between them.

Data saturation had been reached as no new themes were emerging on data analysis of the last interview transcript. Vignettes or quotes are used to illustrate aspects of each theme arising from the interview questions presented in Table 9.2.

9.5 Findings

The key findings of the evaluation are:

9.5.1 High Levels of Engagement

-

Engaging with the criteria

Formative tasks engage students with the marking criteria and introduce them to the process of self-reflection on their academic skills. Students commented very positively on how the focus on self-evaluation helped them critique and improve their work. They also claim that using rubrics helped them to focus their efforts, produce work of higher quality, earn better grades and feel less anxious about assignments:

…the tutors went through the criteria with us and gave examples of what a good paper looked like. I used the rubric to make sure I had done what was asked of me and the self- assessment made me fairly confident I would get a B possibly an A. I actually got 74 % [A], my best grade on the course so far. (Module 1 [M1], Student 4[S4])

The self-assessment activity made me really think about the quality of my work because it was easy to look at the rubric in each section and see if I met the criteria. It made me less stressed about handing it in because I felt confident that I had passed (M1, S6,)

Students on the research methods module (Module 3) used assess the on-going progress of their work. This was perhaps because of the more independent nature of a research project and the different layout of the rubric:

I use it to plan each section of my research proposal to make sure I covered everything (M3, S18)

However, some students also claimed that they did not use the criteria. This may have been because: rubrics were offered as optional tools. Some individuals may have felt confident they were progressing satisfactorily and the extra work involved in using rubrics on top of their very heavy assessment load was a disincentive.

I’ve done a degree already so didn’t really use it (M3, S13)

My supervisor was brilliant and explained things really well so I only used it at the end as I had a last minute panic that I’d forgot something (M3, S4)

All of the activities required the students to act as assessors and so they are taking a critical perspective on the tasks that they are marking. Engaging with each other. A particularly impactful feature of using peer assessment is that the students see how other students tackle the same task which has additional benefits which include them actively seeking clarification on the assessment criterion (they had not in Module 1 when they self-assessed) and checking their own work thoroughly to make sure their peer had not made a mistake.

I learned a lot from seeing how the others got on with the task (M2, S1)

I could hear what other people were saying which helped me think about what I was saying about the work I marked- not just I liked it but this relates to the criteria because… (M2, S9)

In the peer assessment task (Module 2), essays were handed back into the lecturer and returned to their owner to review the comments against the criteria and reflect on whether or not they felt the grade assigned was fair. Most of the students then started checking the accuracy of their mark and feedback for themselves:

When I got my essay back I remarked it myself to make sure they hadn’t made a mistake and given me a lower grade (M2, S2)

They considered it to be high stakes because they were marking someone else’s work thus were more rigorous in the task.

I felt under a lot of pressure to be fair and give the other student’s work an accurate mark and good feedback because someone else was doing the same with my work. (M2, S10)

One student also offered some appreciation for the role of the tutor in the assessment process:

I had no idea how hard it was to mark an essay and how long it took (M2, S3)

All of this appeared to help them to develop their reflective capacity, self-awareness and deeper understanding of the assessment process and its role in learning.

9.5.2 Improvement in Consistency of Grades and Feedback

Students in all modules also commented on the levels of consistency of the amount and quality of feedback across the cohort, although there were mixed views on this:

I liked the fact we got lots of feedback telling us what we had done well or not so well in the essay and as this was the same descriptions [criteria] that we’d been using in the rubric. There was more what the tutor calls ‘feed forward’ than I normally get but as it is the last module I can’t really learn from it. (M3, S14)

My feedback was the same as other peoples, so I don’t even though if the tutor actually read it. (M3, S1)

The sentiment of the second comment was also seen in some shape or form in all of the other module examples. The students had asked for ‘consistency’ of feedback, language but when that aspect was addressed the new complaint was that they were ‘getting the same comments as [their] friends’. There was also some variation reported in the volume and usefulness of the feed forward section. Some tutors took the opportunity to provide specific comments on the quality and creativity of the work for students attaining the higher grades providing positive encouragement to publish or go on to a higher degree, which was widely appreciated by the students who received it. This was also picked up in the documentation review across the module examples. This was a marked improvement from the original audit findings, which showed a lack of written commentary and feed forward for high performing students.

Additionally, the documentation review revealed high levels of consistency between markers in amount of feedback and quality of feedback for individual student development. The grade given and the feedback provided were also consistent, i.e. the amount and quality of the written comments reflected the development required of the student to improve.

9.5.3 Empowerment

Ultimately, the combination of the rubrics in themselves and a more collegiate and engaging process appeared to have led to a sense of empowerment in the students over their own learning and their wider university experience. The students that were involved in the collaborative construction of the task and rubric provided them with a say in the choice of topic, method, criteria, weighting and timing of assessments which provided a sense of ownership, they described the experience as like:

being in the ‘circle of trust’ like Ben Stiller in ‘Meet the Fockers’ (M4, SC1)

getting a insider tip on a horse race or football match’ (M4, SC3)

The overall feeling appears to be one of belonging, being ‘part of the gang’, feeling important, valued, listened to, and also the ‘insider tip’ comment was suggestive of that engaging more got you a better mark although it is unclear as to why they felt that. One of the student consultants, however, drew attention to the power relations at play despite the faculty’s best efforts:

I felt a bit awkward, like I didn’t really belong there. It didn’t seem right that the other students were making suggestions to the staff- seemed a bit cocky really, so I didn’t really say anything… I suppose I was worried that if they didn’t like what I had to say it might affect my mark [grade]. (M4, CS2)

The module evaluations revealed somewhat of a dichotomy through. Some students (n = 4) who weren’t involved in the design phase stated that they felt ‘disadvantaged’ because they hadn’t been involved. Others commented that they wish they had been more involved as the student consultants ‘seemed more confident’, although others were more disparaging suggesting that ‘they were matey [friends with] with the lecturers’ and ‘always took the lead giving nobody else a chance’. It is unclear (and unmeasured) as to whether it was the engagement in the design team that gave them the confidence or leadership role (positively or negatively) or whether it was those characteristics that made them volunteer in the first place.

9.5.4 Discussion and Conclusions—Creating Rubrics… but oh so Much More

The overarching aim of this illustrative case study was to improve consistency and transparency of the assessment, marking and feedback process and for the most part, this has been achieved. However, the secondary but arguably more impactful outcome has been more active engagement of staff and students in the assessment process resulting in feelings of empowerment in both.

The findings indicated that the students in all Module Examples perceived the rubrics to be comprehensive, and linked to the specific assignment questions.

Students used rubrics in a variety of ways to ensure that they had met the assessment criteria and to improve their work as instructed by the tutor and some also used them as a guide to structure and assess the progress of their work.

Nearly all of the activities provided students with the opportunity to gain immediate and detailed feedback unique to that particular module.

Interviews and anecdotal evidence from conversations after the faculty development workshops indicated that the faculty collaborative approach to developing rubrics meant that all academic staff had a consistent message, were using the DECIDE model to shape their work.

Module teams had ensured greater levels of consistency and quality in both the grading and feedback provided to the students.

It was, however, the approach to marking and moderation that really made a difference in the consistency and justification of marking process. This has resulted in a recommendation to the Faculty Senior Team that time be allocated in the staff workload model for team-based assessment, i.e. to diffuse more widely the benefits gained from this work into other modules.

Module-specific rubrics proved the key active ingredient to ensure transparency in assessment criteria. The range of different approaches to explain rubrics used across the modules suggests that it is not how this is done, but that it is done that is of importance.

-

(a)

The rubrics were introduced to the students at the start (with the above explanation), in the middle (as an activity) and towards the end before they carried out their assignments. This means that the students could use the rubrics as an aid to planning, writing their assignments and assessing their performance. This approach appears to underpin their claims that the rubrics have helped them focus their efforts and produce work of higher quality, but additionally feel much more prepared and less anxious about assignments.

-

(b)

It is necessary to have some discussion with the group about the marks and provide some quality assurance that the marking criteria had been fairly applied. For this reason, it is recommended that it is an anonymous activity (i.e. the papers are blind-marked so that the student cannot be identified) and have academic staff available for questions and monitoring

-

(c)

Having the assessment information in written format in the module handbook and digitally on TurnitIn demonstrated both transparency and consistency and minimised the potential for conflicting advice between members of staff, students not having to rely on their own notes and interpretations of the verbal explanations provided which potentially could lead to misunderstanding.

The Assessment and Feedback Project succeeded in making the academic world transparent by inviting all staff to the assessment development meetings. In, some modules students and stakeholders actively participated in the project design and activity. All staff and students who provided feedback talked about having a sense of ownership and how empowering that is. Even staff and students who did not actively get involved in the design phase were pleased that they had been asked and several commented that they now wished they had been more involved.

In-class activities, empowerment came from sharing the assessment criteria (transparency) and being taught how to use it to improve (engagement) with the learning process. Students grew in confidence about the assessment judgments they were making. They used their knowledge and the skills as assessor, which developed their academic skills, professional skills and attributes. Building the capacity to make assessment judgments needs to be an overt part of any curriculum and one that needs to be fostered (Boud and Falchikov 2007).

9.6 Conclusion

The illuminative case study within the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery was a reminder that teachers, their students and clinical teaching partners need the conditions to develop their own approach to improving feedback and assessment. However, their assessment and feedback project was initiated, informed by and reflected the values and priorities of a university wide strategy and project. In essence, it was a faculty project created to respond to their own demonstrable challenges (and aspirations) that was prioritised and enabled by the university.

The University’s focus on feedback and assessment was externally driven. It was in part a response to policy and policy instruments. In this example, the need for change was from persistent external pressure, (NSS results and the associated league tables and heightened student expectations), but the change itself came from within. The model of change here is not one of top-down change but rather a systematic identification of a need, seen from the perspective of range of stakeholders, that is examined and addressed at local level. This model is owned, governed and makes sense to the staff in the faculty. It respects context and the importance of role of faculty and students in driving practice improvements in learning and assessment.

Issues/Questions for Reflection

-

Higher educational institutions need to pay close attention to prevailing and emerging governmental policies to anticipate how they may help develop and/or challenge educational practices. What processes are there within your institution to do this?

-

To what extent does your institution’s educational strategies and practices respond to government policy and with what effects?

-

This chapter provides evidence that an appreciative evaluative approach enables broad engagement in change and a more nuanced response to improving assessment practices. How are programme teams and academic departments engaged in curriculum planning and curriculum review discussions in your context? Do the discussions adopt a deficit evaluation of a current situation, (i.e. what is not working and how do we fix it?) or an appreciative inquiry approach used (i.e. what is currently working well, and how can we do more of that)?

References

Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university (2nd ed.). Berkshire, NY: Open University Press.

Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2007). Rethinking assessment in higher education: Learning for the longer term. Abingdon: Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Garnham, N. (2002). Information Society’s theory or ideology: A critical perspective on technology, education and employment in the information age. In W. H. Dutton & B. D. Loader (Eds.), Digital academe. The new media and institutions of higher education and learning. London. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Routledge, Springer.

Hammond, N. (2007). Preface. In A. Jenkins & M. Healey (Eds.), Linking teaching and research in disciplines and departments (p. 3). Retrieved September 10, 2008, from (2012) Academic identities and research-informed learning and teaching: issues in higher education in The United Kingdom (p. 236) http://www.shapeoftraining.co.uk/reviewsofar/1788.aspin

Jackson, C., & Barriball, L. (2013). Audit of assessment practices in the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery (unpublished paper).

McKee, A. (2012). Academic identities and research-informed learning and teaching: Issues in higher education in The United Kingdom (p. 236). http://www.shapeoftraining.co.uk/reviewsofar/1788.aspin. In A. Mc Kee & M. Eraut (Eds.), Learning trajectories, innovation and identity for professional development. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Springer.

Merry, S., Price, M., Carless D., & Taras, M. (2013). Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue with students. London, New York: Routledge.

Price, M., Handley, K., O’Donovan, B., Rust, C., & Miller, J. (2013). Assessment feedback: An agenda for change. In S. Merry, M. Price, D. Carless, & M. Taras (Eds.), Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue with students. London: Routledge.

Rapley, T. (2010). Some pragmatics of qualitative data analysis. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice (pp. 273–290). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Reddy, Y. M., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(4), 435–448.

Russell, M. B., Bygate, G., & Barefoot, H. (2013). Making learning oriented assessment the experience of all our students. In S. Merry, M. Price, D. Carless, & M. Taras (Eds.), Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue with students. London: Routledge.

Russell-Westhead (2014). The Decide Model. A presentation to the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery.

Further Readings

Boud, D., Lawson, R., & Thompson, D. G. (2013). Does student engagement in self-assessment calibrate their judgement over time? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(8), 941–956.

Bovill, C., Aitkin, G., Hutchinson, J., Morrison, F., Scott, A., & Sotannde, S. (2010). Experiences of learning through collaborative evaluation from a masters programme in professional education. International Journal for Academic Development, 15(2), 143–145.

Campbell, F., Eland, J., Rumpus, A., & Shacklock, R. (2009). Hearing the student voice: Involving students in curriculum design and development. Retrieved June 1st 2011, from http://www2.napier.ac.uk/studentvoices/curriculum/download/StudentVoice2009_Final.pdf

Dunne, E., & Zandstra, R. (2011). Students as change agents: New ways of engaging with learning and teaching in higher education. Bristol: ESCalate/Higher Education Academy.

Greenaway, D. (2013). The future shape of training. http://www.shapeoftraining.co.uk/reviewsofar/1788.asp. Accessed July 6, 2015.

Healey, M., Flint, A., & Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York: Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Engagement_through_partnership.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2015.

Healey, M., Mason O’Connor, K., & Broadfoot, P. (2010). Reflections on engaging students in the process and product of strategy development for learning, teaching, and assessment: An institutional case study. International Journal for Academic Development, 15(1), 19–32.

Health Education England-Kent, Surrey and Sussex. (2013). The sound of the student and trainee voice. http://kss.hee.nhs.uk/events/studentvoice/accessed, March 10, 2014.

Krause, K., & Armitage, L. (2014). Student engagement to improve student retention and success: A synthesis of Australian literature. York: Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Australian_student_engagement_lit_syn_2.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2015.

Krause, K. L., Hartley, R., James, R., & McInnis, C. (2005). The first-year experience in Australian universities: Findings from a decade of national studies. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nicol, D., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

Nordrum, L., Evans, K., & Gustafsson, M. (2013). Comparing student learning experiences of in-text commentary and rubric-articulated feedback: Strategies for formative assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(8), 919–940.

Panadero, E., & Dochy, F. (2014). Student self-assessment: Assessment, learning and empowerment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(7), 895–897.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: A review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129–144.

Price, M., O’Donovan, B., Rust C., & Carroll, J. (2008). Brookes eJournal of learning and teaching: Promoting good practice in learning, teaching and assessment in higher education. Assessment Standards: A Manifesto for Change, 2(3), 1–2.

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change: Final report from the what works? Student retention & success programme. York: Higher Education Academy.

Thornton, R., & Chapman, H. (2000). Student voice in curriculum making. Journal of Nursing Education, 39(3), 124–132.

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assessment in Education, 14(3), 281–294.

Trowler, P. (2002). The Future Shape of Training. Final Report, commissioned by Health Education England (p. 55). Gildredge, Abingdon: Education Policy. http://www.shapeoftraining.co.uk/reviewsofar/1788.asp. Accessed on March 9, 2014.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weller, S., & Kandiko, C. B. (2013). Students as co-developers of learning and teaching: Conceptualising ‘student voice’ in professional development. A paper presented at Society for Research into Higher Education, Celtic Manor, Wales (UK).

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Westhead, M. (2012). Cultivating student voice to enhance the curriculum and influence institutional change: The case of the non-traditional student. In 6th Excellence in Teaching Conference Annual Proceedings (pp. 59–74).

Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Yorke, M., & Longden, B. (2008). The first-year experience of higher education in the UK. York, UK: Higher Education Academy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

King’s College London is the fourth oldest university in England. Founded in 1829 by King George IV and the Duke of Wellington, it was one of the two founding colleges of the University of London in 1836. King’s has a world-renowned reputation in a number of disciplinary areas and ranks highly in international and national university league tables.

Organised in eight academic Faculties, King’s has research-intensive orientation and is hence a member of the UK Russell Group. By their own definition, the UK Russell Group represents 24 leading UK universities which are committed to maintaining the very best research, an outstanding teaching and learning experience, and unrivalled links with business and the public sector.

Approximately 25,000 students study at King’s, the majority of which study on a full time basis. Around 15,000 students are registered on undergraduate programmes, 7500 are registered on postgraduate taught programmes and the remaining (circa) 2500 are registered on postgraduate research programmes. Having a significant research-intensive history and culture is not without its challenges. King’s is facing up to these challenges and is continually seeking to enhance the educational experience of its students. The College’s research culture can also benefit its students and society.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Russell, M., McKee, A., Russell-Westhead, M. (2016). Assessing Across Domains of Study: Issues in Interdisciplinary Assessment. In: Wimmers, P., Mentkowski, M. (eds) Assessing Competence in Professional Performance across Disciplines and Professions. Innovation and Change in Professional Education, vol 13. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30064-1_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30064-1_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-30062-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-30064-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)