Abstract

Self-Directed Learning (SDL) is gaining interest, as online learning is increasingly learner-centered. FutureLearn courses provide an array of online interactions and content deliveries, which have allowed the authors to investigate a diversity of SDL elements. This preliminary research examines the SDL taking place in three FutureLearn courses, and categorises those learner actions into meaningful elements and dimensions for the learners. The SDL framework by Bouchard [1] is used to interpret the self-reported findings coming from active learners. The research uses a grounded theory approach to look for learner experiences related to four dimensions (algorithmic, conative, semiotic, and economic) of the Bouchard [1] framework, and to discover new dimensions. Various research instruments are used: online surveys, learning logs, and one-on-one interviews, all collected pre-, during, or post-course. The initial adaptation of Bouchard’s framework offers insights into SDL, its meaning, and value as perceived by the learners.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This paper shares findings arising from the initial coding iteration of self-reported data from FutureLearn (MOOC) learners, to investigate the participants’ Self-Directed Learning (SDL) experiences. The Bouchard framework [1] presents SDL dimensions using a specific terminology: algorithmic, conative, semiotic and economic. This allows SDL experiences to be categorized and interpreted from four important online learning angles: the pedagogical, psychological, infrastructural, and economic elements. As contemporary online learning is becoming increasingly learner-centered [2–4] it is becoming an increasingly important educational concept.

There is currently a research gap in understanding the full range of SDL dimensions that are used by the learner when s/he engages in an online course [4, 5].

2 Self-directed Learning

In this study, SDL relates to research into adult learning, based on the andragogy concept of Knowles [6], but also embedding technology as an influencing factor for SDL. Knowles [6] described SDL broadly as “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, to diagnose their learning needs, formulate learning goals, identify resources for learning, select and implement learning strategies, and evaluate learning outcomes’ (p. 18).

Students need to have a high level of self-direction to succeed in mLearning and online learning environments [7]. Learners themselves also consider that achieving the level of self-direction necessary for successful learning in a MOOC is related to prior experience and its resulting self-efficacy [8, 9].

Any SDL framework will need to take into account all these dimensions in a structured way. The Bouchard framework offers such a set of SDL dimensions.

3 The Bouchard Framework

Based on interviews with 40 professionals, Bouchard examined four dimensions of self-directed learning: the algorithmic, conative, semiotic, and economic. Bouchard [1] concluded that only through the careful application of multi-dimensional models can progress be made towards creating environments that truly support the emergence and development of SDL. The work of Bouchard builds upon research performed by Long [10] who provided two fundamental ways in which learning could be learner-controlled: psychological and pedagogical. Bouchard rethought the concepts of Long (psychological became the conative dimension, pedagogical became the algorithmic dimension) and he added two additional dimensions: a semiotic and economic dimension. As a result, Bouchard’s framework [1] seemed well suited to use for a first iteration (bird’s eye analysis), as it provided a schematic for SDL taking into account different dimensions related to online learning.

4 Methodology

To plan and analyse this study, a Grounded Theory (GT) methodology was chosen to organize the different stages of questioning the learners, and to set up research instruments [11]. GT fits research looking for meaning as perceived by the research subjects and permits data like learning experiences to be analysed [12].

4.1 Data Collection

The UK-led MOOC initiative FutureLearn was launched in 2013, and is offering free courses built upon a pedagogy that mixes mobile learning and social learning approaches [13]. This study collected data from three FutureLearn courses, which ran between 1 September and 15 November 2014. The 52 research participants were all experienced online learners. This was a decision based upon outcomes indicating that prior MOOC experience results in more efficient SDL [4, 8]. Experienced online learner covers learners that had prior MOOC and/or online learning experience, and had three or more years of social media experience.

This study uses elicited data (written, digitally delivered, and audio data) from 52 participants who gave full consent prior to the research. The research consisted of three phases to fully capture the SDL experience.

-

Phase 1 – expectations (pre-course): gathering the expectations of the FutureLearn participants by collecting data through an online survey.

-

Phase 2 –learning logs (during course): the participants kept learning logs: filled in every 2 weeks probing the actual learning experiences.

-

Phase 3 – reflections (post-course): structured one-on-one interviews investigating differences between the learning expectations and the actual experiences in regard to SDL.

The data corpus consisted of 792 pages of text coming from learning logs, 115 pages of online survey answers, and 48 pages of interview transcript texts.

4.2 Data Analysis

The data analysis is in its initial coding stage following grounded theory coding suggestions [11], providing first impressions. Constructing theory and relating it to interactions was crucial for selecting GT as a method [11]. In order to analyse and interpret the rich, elicited data, memoing (making researcher assumptions transparent) and the following coding iteration was followed: initial coding, line-by-line coding and focused coding. Allowing the researcher to separate, sort and synthesize large amounts of data. Once the initial categories emerged, those categories were compared to the Bouchard Framework dimensions. The examples below are only a selection of the elements found, due to space restrictions.

5 Sharing Initial Findings

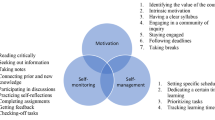

Following the analysis, two of the four dimensions (i.e. semiotic and economic dimension) needed to be revised to fit contemporary, massive online learning (e.g. adding collaborative learning). In addition to that, the algorithmic and conative dimensions harboured elements that needed some updating to match them with current FutureLearn options (e.g., pedagogy, available learner interactions). This resulted in additional dimensions, listed after Bouchard’s known dimensions for each group of elements.

5.1 Algorithmic Dimension

The pedagogical options, and more specifically how the learner uses or interprets them for their own use, are gathered under the algorithmic dimension (Table 1).

5.2 Conative Dimension

The conative dimension groups elements related to the social and psychological profile, as well as the context the learner is in (Table 2).

5.3 Semiotic Dimension

In contemporary online learning each type of media possesses its own intrinsic characteristics that facilitate or hinder learning, depending on each individual’s learning preference [1], which brings along a new, wide variety of semiotic dimensions (Table 3).

5.4 Economic Dimension

Bouchard [1] saw the perceived economic value of its knowledge in the marketplace, either as an professional asset or as a means of production (Table 4).

6 Summary and Future Work

From these preliminary findings promising SDL dimensions were distilled coming from SDL experiences shared by FutureLearn participants. The Bouchard framework needs to be adapted once higher-level dimensions emerge from this on-going study. Once the full analysis is finished, it will potentially reshape Bouchard’s framework, and offer a framework for SDL in FutureLearn courses and MOOCs.

References

Bouchard, P.: Pedagogy without a teacher: what are the limits. Int. J. Self-Directed Learn. 6(2), 13–22 (2009)

Siemens, G.: Connectivism: a learning theory for the digital age. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2(1), 3–10 (2005)

Downes, S.: Evaluating a MOOC [Web log post]. http://halfanhour.blogspot.ca/2013/03/evaluat-ing-mooc.html (2013). Accessed 14 June 2015

Kop, R., Fournier, H.: New dimensions to self-directed learning in an open networked learning environment. Int. J. Self-Directed Learn. 7(2), 2–20 (2011)

de Waard, I., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Sharples, M.: Self-directed learning in trial FutureLearn courses. In: Proceedings of the European Stakeholder Summit 2015, pp. 234–243 (2015)

Knowles, M.S.: Self-Directed Learning. Association Press, New York (1975)

Song, L., Hill, J.R.: A conceptual model for understanding self-directed learning in online environments. J. Interact. Online Learn. 6(1), 27–42 (2007)

Milligan, C., Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A.: Patterns of engagement in massive open online courses. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 9(2), 149–159 (2013)

de Waard, I.: Analyzing the Impact of Mobile Access on Learner Interactions in a MOOC. Masters dissertation, Athabasca University. https://dt.athabascau.ca/jspui/bitstream/10791/23/1/Master%20thesis%20Inge%20de%20Waard%20MEd%20publication%20final%20reviewed.pdf (2013)

Long, H.B.: Philosophical, psychological, and practical justifications for studying self-directed learning. In: Long, H.B., Associates, Self-directed Learning: Application and Research. Oklahoma Research Center, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73037 (1992)

Charmaz, K.: Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Pine Forge Press, CA (2006)

Creswell, J.W.: Qualitative Inquiry And Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publications, London (2006)

Sharples, M.: FutureLearn and Pedagogy. Internal presentation circulated during Learning Fair, The Open University (2013)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

de Waard, I., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Sharples, M. (2015). Investigating Self-directed Learning Dimensions: Adapting the Bouchard Framework. In: Conole, G., Klobučar, T., Rensing, C., Konert, J., Lavoué, E. (eds) Design for Teaching and Learning in a Networked World. EC-TEL 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9307. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24258-3_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24258-3_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-24257-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-24258-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)