Abstract

At the center of the social emotions are reactions to the positive and negative fate of others and to the perceived fulfillment and violation of social and moral norms. Using pity and guilt as representatives of these two groups of social emotions, I investigate their generation, nature and function from the perspective of CBDTE, a (sketch of a) Computational model of the Belief-Desire Theory emotion. The central assumption of CBDTE is that a core subset of human emotions are the products of hardwired mechanisms whose primary function is to subserve the monitoring and updating of the belief-desire system. The emotion mechanisms work like sensory transducers; however, instead of sensing the world, they monitor the belief-desire system and signal important changes in this system, in particular the fulfillment and frustration of desires and the confirmation and disconfirmation of beliefs. Social emotions are accommodated into CBDTE by assuming that the proximate beliefs and desires that cause them are derived from special kinds of desire. Specifically, pity is a form of displeasure that is experienced if an altruistic desire is frustrated by the negative fate of another person; whereas guilt is a form of displeasure that is experienced if a nonegoistic desire to comply with a norm is frustrated by an own action. The intra-system function of these emotions is to signal the frustration of altruistic desires (pity) and of nonegoistic desires to comply with a norm (guilt) to other cognitive subsystems, to globally prepare and motivate the agent to deal with them. The communication of social emotions serves to reveal the person’s social (nonegoistic) desires to others: Her altruistic concern for others, and her nonegoistic caring for the observance of social norms.

Parts of this article are based on a German book chapter (Reisenzein 2010). I am grateful to Cristiano Castelfranchi for his helpful comments to a previous version of the manuscript.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

“Social emotions” can be roughly defined as emotions whose elicitors and objects essentially involve social agents (other persons, groups, institutions). Some social emotions, such as love and hate, attraction and repulsion, trust and distrust seem to have social agents themselves as objects; whereas others, such as anger about another’s norm-violation or envy of another’s good fortune, are directed at propositions or states of affairs that involve social agents. In this article, I am concerned with these “propositional” social emotions. At their core are two emotion families: the fortune-of-others emotions (Ortony et al. 1988), i.e. emotional reactions to the positive or negative fate of other people, such as joy for another, envy, pity and Schadenfreude (gloating); and the norm-based emotions, i.e. emotional reactions to the perceived violation and fulfillment of social and moral norms, such as guilt, shame, indignation and moral elevation. In this article, I investigate the generation, nature and function of these two kinds of social emotions from the perspective of CBDTE (Reisenzein 2009a, b; also see Reisenzein 2001, 2012a, b; Reisenzein and Junge 2012), a (sketch of a) computational (C) model of the belief-desire theory of emotion (BDTE). In Section 1, I summarize CBDTE. In Section 2, I discuss how CBDTE explains the social emotions, using the examples of pity and guilt.

1 The Computational Belief-Desire Theory of Emotion

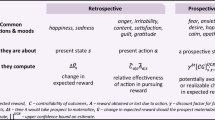

The starting point of the computational model of emotion sketched in Reisenzein (2009a, b; see also, Reisenzein 2001) is the cognitive-motivational, or belief-desire theory of emotion (BDTE). BDTE, in turn, is a member of the family of cognitive emotion theories that have dominated discussions of emotions during the past 30 years in both psychology and philosophy (for reviews, see e.g., Ellsworth and Scherer 2003; Goldie 2007). As explained below, BDTE differs from the standard version of cognitive emotion theory (the cognitive-evaluative theory of emotion) in a number of foundational assumptions that allow BDTE to escape several criticisms of the standard view; or at least so its proponents argue. Although BDTE has been primarily promoted by philosophers (see especially Davis 1981; Green 1992; Marks 1982; Searle 1983), it also has adherents in psychology (e.g., Castelfranchi and Miceli 2009; Oatley 2009; Reisenzein 2001, 2009a; Roseman 1979). Recent formal reconstructions of cognitive emotion theories (e.g., Adam et al. 2009; Steunebrink et al. 2012) have also adopted the belief-desire framework (see Reisenzein et al. 2013).

The most important difference between BDTE and the standard version of cognitive emotion theory concerns what a pioneer BDTE theorist, the Austrian philosopher-psychologist Alexius Meinong (1894), called the “psychological preconditions” of emotions: the mental states required for having an emotion. According to the standard version of cognitive emotion theory, the cognitive-evaluative theory of emotion—known as appraisal theory in psychology (e.g., Arnold 1960; Frijda 1986; Lazarus 1991; Scherer 2001) and as the judgment theory of emotions in philosophy (e.g., Solomon 1976; Nussbaum 2001)—emotions presuppose certain factual and evaluative cognitions about their eliciting events, which in their paradigmatic form are factual and evaluative beliefs. In contrast, BDTE is a cognitive-motivational theory of emotion: It assumes that emotions depend not only on beliefs (i.e., cognitive or informational states) but also on desires (i.e., motivational states) (for an elaboration of the distinction between beliefs and desires see e.g., Green 1992; Smith 1994).

To illustrate the difference between the two theories, assume that Maria feels happy that Mr. Schroiber was elected chancellor. According to the cognitive-evaluative theory of emotion, Maria experiences happiness about this state of affairs p only if, and under “normal working conditions” always if (see Reisenzein 2012a), she comes to (firmly) believe that p obtains, and evaluates p as good for herself (i.e., believes that p is good for her). In contrast, according to BDTE, Maria feels happy about p if she comes to believe p, and if she desires p. Although many proponents of the theory (including most psychological appraisal theorists) acknowledge that desires are also important for emotions, inasmuch as appraisals of events express their relevance for the person’s motives, desires, or goals (e.g., Lazarus 1991; Scherer 2001; Ortony et al. 1988), the link between desires and emotions is held to be mediated by appraisals (Reisenzein 2006a). In contrast, according to BDTE, emotions are based directly on desires and (typically factual) beliefs (Green 1992; Reisenzein 2009b; see, also Castelfranchi and Miceli 2009). Although this difference between the two theories may at first sight appear to be small, it has a profound implication: It implies that the evaluative cognitions that are at the center of the cognitive-evaluative theory are in fact neither necessary nor, together with factual beliefs, sufficient for emotions. All that is needed for feeling happy about p is desiring p and believing that p obtains. It is not necessary to, in addition, believe that p is good for oneself, or fulfills a desire.

It should be noted that in contrast to other belief-desire theorists (e.g., Castelfranchi and Miceli 2009; Marks 1982; Green 1992), who assume that beliefs and desires are components of the emotion, I endorse a causalist reading of BDTE; that is, I assume that the belief and desire together cause the emotion, which is (accordingly) regarded as a separate mental state.Footnote 1 Arguments for this position are presented in Reisenzein (2012a).

BDTE does not claim to be able to explain all mental states that may be presystematically subsumed under the category “emotion”. However, the theory wants to explain all those emotions that seem to be directed at propositional objects, that is, actual or possible states of affairs. According to my explication of BDTE, all of these “propositional” emotions are reactions to the cognized actual or potential fulfillment or frustration of desires; plus, in some cases (e.g., relief and disappointment), the confirmation or disconfirmation of beliefs (Reisenzein 2009a). For example, Maria is happy that p (e.g., that Mr. Schroiber was elected chancellor) if she desires p and now comes to believe firmly (i.e., is certain) that p is the case; whereas Maria is unhappy that p if she is averse to p (which is here interpreted as: she desires ¬p [not-p]) and now comes to believe firmly that p is the case. Maria hopes that p if she desires p but is uncertain about p (i.e., her subjective probability that p is the case is between 0 and 1), and she fears p if she is averse to p and is uncertain about p. Maria is surprised that p if she up to now believed ¬p and now comes to believe p; she is disappointed that ¬p if she desires p and up to now believed p, but now comes to believe ¬p; and she is relieved that ¬p if she is averse to p and up to now believed p, but now comes to believe ¬p. The analysis of social emotions is discussed below.

1.1 A Computational Model of BDTE

Like most traditional theories of psychology, including most emotion theories, BDTE is formulated on the “intentional level” of system analysis (in Dennett’s 1971, sense) familiar from common-sense psychology; in fact, BDTE is an explication of a core part of the implicit theory of emotion contained in common-sense psychology (Heider 1958). However, I believe with Sloman (1992) that some basic questions of emotion theory can only be answered if one moves beyond the intentional level of system analysis to the “design level”, the level of the computational architecture (Reisenzein 2009a, b). This requires making assumptions about the representational-computational system that generates the mental states (beliefs, desires, emotions) assumed in BDTE. The computational architecture that I have adopted as the basis for a computational model of BDTE assumes a propositional representation system, a “language of thought” (Fodor 1975, 1987). The main reason for this architectural choice is that, in contrast to other proposed representation systems (e.g., image-like representations, or subsymbolic distributed representations of the neural network type), a language of thought provides for a plausible and transparent computational analysis of beliefs and desires. In fact, considering that the intentional objects of beliefs and desires are generally regarded as propositions or states of affairs, and that propositions are the entities described by (are “the meanings of”) declarative sentences, a propositional representation system seems to be the natural choice for the computational modeling of beliefs and desires. If one combines this assumption about the representational format of the contents of beliefs and desires with the basic postulate of cognitive science, that mental processes are computations with internal representations, then one immediately obtains Fodor’s (1987) thesis that the mental states of believing and desiring are special modes of processing propositional representations, that is, sentences in the language of thought. To use Fodor’s metaphor, believing that a state of affairs p is the case consists, computationally speaking, of having a token of a sentence s that represents p in a special memory store (the “belief store”), whereas desiring p consists of having a token of a sentence s that represents p in another memory store (the “desire store”). For example, prior to Schroiber’s election, Maria desired victory for Schroiber in the election but believed that he would not win it. On the computational level, this means that prior to Schroiber’s election, Maria’s desire store contained among others the sentence “Schroiber will win the election”, and her belief store contained the sentence “Schroiber will not win the election.”

CBDTE also follows Fodor (1975) in assuming that at least the central part of the language of thought is innate. In particular, CBDTE assumes that the innate components of the language of thought comprise a set of hardwired maintenance and updating mechanisms (Reisenzein 2009a). At the core of these mechanisms are two comparator devices, a belief-belief comparator (BBC) and a belief-desire comparator (BDC). As will be explained shortly, these comparators play a pivotal role in the generation of emotions. The BBC compares newly acquired beliefs to pre-existing beliefs, whereas the BDC compares them to pre-existing desires. Computationally speaking, using again Fodor’s “store” metaphor, the BBC and BDC compare the mentalese sentence tokens s new in a special store reserved for newly acquired beliefs, with the sentences s old currently in the stores for pre-existing beliefs and desires. If either a match (s new is identical to s old ) or a mismatch (s new is identical to ¬s old ) is detected, the comparators generate an output that signals the detection of the match or mismatch.

CBDTE assumes that the comparator mechanisms operate automatically (i.e., without intention, and preconsciously) and that their outputs are nonpropositional and nonconceptual: They consist of signals that vary in kind and intensity, but have no internal structure, and hence are analogous to sensations (e.g., of tone or temperature, Wundt 1896). These signals carry information about the degree of (un-) expectedness and (un-) desiredness of the propositional contents of newly acquired beliefs; but they do not represent the contents themselves. In our example, Maria’s BBC detects that the sentence s new representing that Schroiber wins the election, is inconsistent with (is the negation of) the content s old of a pre-existing belief; and Maria’s BDC detects that s new is identical to the content s old of an existing desire. As a consequence, Maria’s BBC outputs information about the detection of a mismatch—the information that one of Maria’s beliefs has just been disconfirmed by new information; whereas Maria’s BDC outputs information about a match—the information that one of Maria’s desires has just been fulfilled.

To complete the picture, CBDTE assumes that the outputs generated by the BBC and BDC have important functional consequences in the cognitive system. First, attention is automatically focused on the content of the newly acquired belief that gave rise to match or mismatch—in Maria’s case, Schroiber’s unexpected but desired election victory. Second, some minimal updating of the belief-desire system takes place automatically: Sentences representing disconfirmed beliefs are deleted from the belief store, and sentences representing states of affairs now believed to obtain are deleted from the desire store. Third, BBC and BDC output signals that exceed a certain threshold of intensity give rise, directly or indirectly, to unique conscious feeling qualities: the feelings of surprise and expectancy confirmation (BBC), and the feelings of pleasure and displeasure (BDC). It is assumed that the simultaneous experience of an emotional feeling and the focusing of attention on the content of the belief that caused it, give rise to the subjective impression that emotions are directed at objects (Reisenzein 2009a).

In sum, CBDTE posits that emotions are the results of computations in a propositional representation system that supports beliefs and desires. The core of the belief-desire system is innate, and this innate core includes a set of hardwired monitoring-and-updating mechanisms, the BBC and the BDC. These mechanisms are, in a sense, similar to sensory transducers (sense organs for color, sound, touch, or bodily changes); in particular, their immediate outputs are nonpropositional and nonconceptual, sensation-like signals. However, instead of sensing the world (at least directly), these “internal transducers” sense the current state and state changes of the belief-desire system, as it deals with new information. Emotions result when the comparator mechanisms detect a match or mismatch between newly acquired beliefs and pre-existing beliefs (BBC) or desires (BDC). Hence, according to CBDTE, emotions are intimately related to the updating of the belief-desire system. In fact, the connection could not be tighter: The hardwired comparator mechanisms that service the belief-desire system, the BBC and the BDC, are simultaneously the basic emotion-producing mechanisms. Correspondingly, CBDTE assumes that the evolutionary function of the emotion mechanisms is not to solve domain-specific problems (as proposed by some evolutionary emotion theorists; e.g., Ekman 1992; McDougall 1908/1960; Tooby and Cosmides 1990), but the domain-general task to detect matches and mismatches of newly acquired beliefs with existing beliefs and desires, and to prepare the cognitive system (or agent) to deal with them in a flexible, intelligent way once they have been detected.

As explained in more detail in Reisenzein (2009a, b), CBDTE solves, resolves, or at least gives clear answers to several long-standing controversial questions of emotion theory. For example, CBDTE provides a precise theoretical definition of emotions (Reisenzein 2009b, 2012a): Emotions are the nonpropositional signals generated by the belief- and desire congruence detectors, that are subjectively experienced as unique kinds of feeling. In contrast to other evolutionary emotion theories, CBDTE also provides a principled demarcation of the set of basic emotions: This set includes precisely the different kinds of output of the congruence detectors. At the same time, however, CBDTE speaks against a sharp distinction between “basic” and “nonbasic” emotions: All emotions covered by the theory, however complex or culturally determined they might be in other respects (this concerns in particular the social emotions), are equally basic in the sense that they are all products of innate, hardwired emotion mechanisms, the BBC and the BDC. CBDTE also provides an explanation of the phenomenal quality of emotions—the fact that emotional experiences “feel in a particular way” (Reisenzein 2009b; see also, Reisenzein and Döring 2009)—and it is able to give a plausible picture of the relation of emotions to public language (Reisenzein and Junge 2012). Finally, an extension of CBDTE to “fantasy emotions”—emotions elicited by stage plays, novels, films etc., as well as by the vivid imagination of events—has been proposed in Reisenzein (2012b, c).

2 Social Emotions from the Perspective of CBDTE

Like BDTE, CBDTE assumes that most emotions are variants of a few basic forms. Accordingly, the apparent diversity and complexity of emotional experiences is not due to the existence of many different “discrete” emotion mechanisms, as some emotion theorists have claimed (e.g., McDougall 1908; Ekman 1992; Tooby and Cosmides 1990). Rather, it is due to the fact that humans can have complex beliefs and desires. Specifically, as members of an “ultrasocial” species (Richerson and Boyd 1998), humans have a vital interest in the fate of (certain) others, their actions and mental states, and the effects of their own actions on others (see also, Reisenzein and Junge 2012). That is, these “social objects” are preferred objects of the beliefs and desires of humans. And if these social beliefs and desires are processed by the emotion mechanisms postulated in CBDTE, social emotions may result. The truth of this assumption can only be established by demonstration, that is, by providing analyses of specific social emotions from the perspective of CBDTE. Here, I will analyze pity as the representative of the fortune-of-others emotions, and guilt as the representative of the norm-based emotions; however, the results of the analyses can be generalized, with small adaptations, to other fortunes-of-others emotions and other norm-based emotions respectively. The following analyses are based, on the one hand, on CBDTE, which provides the theoretical framework for the analysis; and on the other hand, on my intuitions about the social emotions.Footnote 2

2.1 Emotional Reactions to the Fate of Others: The Example of Pity

If CBDTE is true, emotional reactions to the positive and negative fate of other people arise, in principle, in the same way as the emotions of self-regarding happiness and unhappiness about a state of affairs. For the case of pity, this means: Pity is a form of unhappiness—one can also say, a feeling of suffering, or a kind of displeasure or mental pain (Miceli and Castelfranchi 1997)—that occurs, like all “propositional” emotions of displeasure, if the belief-desire comparator (BDC) discovers that the content of a newly acquired belief contradicts the content of an existing desire. As an example, imagine that Maria learns that her colleague Karl (= o) has lost his job (= F), and that Maria experiences pity with Karl because of this state of affairs Fo.Footnote 3 According to CBDTE, the proximate causes of Maria’s pity with Karl are her belief that Karl lost his job, Bel(Fo), and her desire that Karl should not lose his job, Des(¬Fo). Given these inputs, Maria’s BDC detects that the content of a newly acquired belief (Fo) contradicts the content of one of her desires (¬Fo) and as a consequence generates a nonpropositional, sensation-like signal that represents the detection of this desire-incongruence, and that is experienced by Maria as a feeling of displeasure or mental pain.Footnote 4

As presented so far, the only difference between pity (for another) and self-regarding unhappiness is that the desire that is frustrated in pity concerns the fate of another social agent. However, this analysis is clearly insufficient to individuate pity as a separate emotion, as a distinct form of unhappiness or emotional suffering. In fact, at second sight this analysis does not even allow to distinguish pity from self-regarding unhappiness. Imagine, for example, that Maria suffers from Karl’s job loss solely because she believes that it will cause her own work situation to deteriorate (she believes that she will have to take over part of Karl’s work), but that apart from this, Maria is completely indifferent to Karl’s fate. In this case—my intuition tells me—Maria will be unhappy that Karl lost his job, but she will not be unhappy with Karl about the loss of his job; or to put it differently, she will feel sorry because of Karl’s job loss, and will feel sorry for herself about his job loss, but she will not feel sorry for Karl because of his job loss—she will not feel pity for Karl (for empirical evidence, see Reisenzein 2002).Footnote 5 Hence, believing that an undesired event has occurred that affects another person is insufficient for experiencing pity for the other. To experience pity for Karl, more is needed on Maria’s part than her desire that Karl is not fired from his job, and her belief that that he has been fired.

Now, whatever this additional factor is, if CBDTE is correct, it cannot be another proximate cause of Maria’s pity. The reason is that, according to CBDTE, being displeased about a state of affairs p has exactly two proximate causes, the belief that p, and the desire that ¬p. Only these two mental representations are (direct) inputs to the BDC, the mechanism that produces hedonic feelings. Therefore, the problem posed by pity for CBDTE—how to individuate pity as a special form of suffering—cannot be solved by assuming that pity has another (direct) mental cause. One could, of course, decide to modify CBDTE to allow this to be the case; but this would mean to give up a basic and (I believe) intuitively compelling idea on which CBDTE is founded, namely the assumption that all (hedonic) emotions result from a match or mismatch between what one believes to be the case, and what one desires. Furthermore, it is not clear what the additional cause of pity—the third input to the BDC—could be.

However, there is another solution: Pity and self-regarding unhappiness could differ in terms of their cognitive-motivational “background”; specifically, they could differ in terms of the beliefs and desires on which the proximate desire for another’s fate is based. In other words, the difference between Maria’s pity with Karl because of its job loss, and her self-regarding sorrow could reside in the grounds or reasons for which Maria finds Karl’s job loss undesirable.

2.1.1 Pity Has a Special Cognitive-Motivational Background

Most desired states of affairs are not desired for their own sake, but because they are believed to lead to other, desired states of affairs, or at least to increase their likelihood of occurrence. In other words, most desires are derived from other, more basic desires. Typically, the derivation of desires form others is achieved with the help of means-ends beliefs (Conte and Castelfranchi 1995; Reisenzein 2006b; Reiss 2004): One desires p 1 because one desires p 2 and believes that p 1 will lead to p 2; one desires p 2 because one desires p 3 and believes that p 2 will lead to p 3; and so on, until one eventually arrives at a state of affairs that one no longer desires as a means to another end, but for its own sake.Footnote 6 Desires for such states of affairs are basic motives. Plausible candidates for basic motives are biological urges (the desire for food, sex, physical integrity, etc.); but many “higher” motives of humans, such as the hedonistic motive, the power motive, the affiliation motive, or the desire for knowledge, are also regarded as basic motives by some authors (see Reisenzein 2006b; Reiss 2004). Of particular importance for the present analysis, according to a school of motivation psychology that dates back to, at least, Adam Smith (1759), if not to Aristotle,Footnote 7 humans have not only egoistic but also altruistic motives: desires for the well-being of (suitable) other people that are not derived from egoistic motives (see Batson and Shaw 1991; Sober and Wilson 1998). That is, we sometimes desire the well-being of others for their own sake, and not because we believe to profit from it. Empirical evidence for the existence of altruistic motives has been provided, in particular, by the social psychologist C. Daniel Batson and his co-workers (e.g., Batson and Shaw 1991). In the following, I will accept the altruism hypothesis as correct. Interestingly, however, the existence of altruistic motives is independently suggested by the analysis of pity proposed here. That is, this analysis suggests that, to explain pity (and other fortune-of-others emotions), specifically to distinguish pity from self-regarding unhappiness, it is necessary to assume that humans have altruistic motives. Hence, the CBDTE analysis of pity provides an independent reason for believing in the existence of altruistic motives (see also Reisenzein 2002).

Maria’s desire that Karl should not lose his job, and similar concrete desires concerning the fate of other people, are certainly not basic motives but are derived from other desires.Footnote 8 This opens up the possibility that pity for another and self-regarding sorrow evoked by another’s fate are based on different background desires. That this is indeed the case, is in fact rather directly suggested by a closer inspection of our example case: If Maria feels only self-regarding sorrow when she learns about Karl’s job loss, then she presumably wants Karl to keep his job only because she believes that Karl’s job loss will harm her own well-being; or in short, that his job loss is bad for her. In contrast, if Maria feels pity for Karl because he lost his job, she presumably desires Karl to keep his job, at least in part, because she believes that the job loss will harm Karl’s welfare, or for short, that it is bad for Karl.

However, Maria’s belief that Karl’s job loss will have negative consequences for him is clearly not by itself sufficient to derive Maria’s desire that Karl should keep his job. In addition to this means-ends belief, Maria must also have another, more basic desire from which the former desire can be derived. The obvious candidate for this background desire is Maria’s desire that good things should happen to Karl and that he be spared bad things, at least within reasonable limits (e.g., that Karl gets what he deserves; see Ortony et al. 1988). By contrast, in the case of Maria’s self-regarding sorrow about Karl’s job loss, her desire that Karl should keep his job is derived from her desire to avoid the negative consequences that Karl’s job loss would have for her (e.g., the extra work she would have to do), together with her belief that this goal will be reached if Karl stays employed.

However, the CBDTE analysis of pity is still not complete. Rather, one must ask further where Maria’s desire for Karl’s welfare stems from. My thesis is: If Maria is to experience pity with Karl about his job loss, rather than just self-regarding unhappiness, then her desire for Karl’s welfare must not be derived (exclusively) from egoistic desires. Rather, her desire for Karl’s welfare must be (at least in part) altruistic. This thesis can be supported by both theoretical and empirical arguments.

First the theoretical arguments. If Maria desires Karl’s general well-being only for egoistic reasons (e.g. because she thinks that, as long as Karl is doing well, he will be an asset rather than a burden) then her concrete desire that Karl should keep his job, which is derived from the former desire, is also egoistic—one cannot derive an altruistic desire from egoistic motives. However, in this case, Maria is in the same kind of motivational situation as when she hopes to profit directly and concretely from Karl’s continued employment (i.e., because she does not have to take over additional work), as discussed earlier. Karl’s job loss should therefore again only cause Maria to feel self-regarding unhappiness, but not pity for Karl. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the desire for the well-being of another person is just the desire that the other should, within reasonable limits, experience good things and should be spared bad things. As argued above, however, the frustration of a single, concrete desire of this kind (e.g., that Karl should keep his job) does not evoke pity if it is purely egoistically motivated. If so, it is hard to see how a desire for many, more abstractly described events of the same kind (“Karl should be spared negative events”) could form the motivational basis of pity.

The empirical support for the claim that, to experience pity for another, one must not desire the other’s welfare for egoistic reasons only, consists of the results of mental simulations of diagnostic hypothetical situations. How would one react emotionally if something negative happens to another person whose welfare one desires only for selfish reasons? As an extreme case, one might imagine a slave who loathes his cruel master but is nonetheless concerned about his well-being because his fate depends completely on that of the master: Any deterioration of the master’s welfare will immediately be felt by the slave. What emotions will this slave experience when he learns that his master has, say, suffered a severe economic loss? Probably self-regarding sorrow, and fear; but according to my intuition, not pity.

However, if Maria’s desire for Karl’ welfare is not derived from egoistic motives, then this desire is either itself a basic motive—that would be a person-specific, basic altruistic motive (i.e., one that concerns a specific person, Karl)—or it is derived from more basic nonegoistic motives. Specifically, Maria’s desire for Karl’s welfare could be derived from her basic altruistic desire that suitable people (such as friends) should experience, within reasonable limits, good things and should be spared bad things.

The proposed CBDTE analysis of pity can be summarized as follows.

CBDTE analysis of pity: Pity about p is a form of unhappiness (suffering, mental pain) about p, that person a experiences if:

-

1a.

a believes that p; with p = Fo = a state of affairs of type F that concerns another person (or group) o; and

-

2b.

a desires that ¬Fo.

-

3.

a’s desire for ¬Fo is based on:

-

3a.

a’s belief that Fo is bad for o (or that ¬Fo is good for o) and

-

3b.

a’s desire that (within reasonable limits), good things and no bad things should happen to o.

-

3a.

-

4.

The desire 3b (that good things and no bad things should happen to o) is not derived from egoistic reasons, but is altruistic.

Because a’s desire for the welfare of the other (3b) is altruistic, the desire for ¬Fo that directly causes the emotion (2b) is altruistic as well. Therefore, the proposed analysis of pity can be abbreviated as follows: Pity about p is a form of unhappiness about p that is caused by the perception (more precisely: the detection by the BDC) that an altruistic desire has been frustrated by p. In contrast, if the desire frustrated by p is egoistic, then one experiences self-regarding unhappiness, or egoistic sorrow. Of course, it is also possible that the desire frustrated by p is partly derived from altruistic and partly from egoistic motives; indeed, this may be the typical situation. For example, Maria could desire Karl’s continued employment both because Karl’s well-being is dear to her heart for altruistic reasons, and because she hopes to profit from Karl’s continued employment. In this case, Maria experiences a mixture of pity and egoistic sorrow (for evidence, see Reisenzein 2002).

2.1.2 Pity Has a Special Intentional Object

There is a second possibility of analyzing pity in CBDTE. The basic idea of this second approach is that the intentional objects of pity—the states of affairs that one feels pity about—are of a special kind, a kind specific for pity. The more general intuition behind this analytic approach is that, although the different instances of a given emotion type (happiness, unhappiness, pity, etc.) have different particular objects (e.g., in the case of pity: Karl has lost his job; Berta’s marriage proposal was rejected; the kitten caught its paw in the trap), all particular objects of a given emotion have something in common, that can therefore be used to individuate the emotion—it is an emotion whose particular objects share this common property. More formally, for each emotion type E there is a property P E such that, for all particular objects p ∈ {p 1, p 2, …, p n} of E, it is true that P E (p). Philosophers call this common property P E of the objects of an emotion E the “formal object” of the emotion E (e.g., Kenny 1963; de Sousa 1987; Teroni 2007). As it turns out, the formal object of an emotion is intimately linked to the emotion’s cognitive and motivational presuppositions, for the features used to define the formal object are precisely the person’s beliefs and desires characteristic for this emotion. Therefore, given any proposed analysis of the beliefs (or the beliefs and desires) characteristic for an emotion, a corresponding formal-object analysis of this emotion falls out as a byproduct. For example, according to BDTE, happiness about p is experienced if one desires p and comes to believe that p is true. Therefore, the formal object of happiness can be described as “the believed occurrence of a desired state of affairs”, or in abbreviated form, “the occurrence of a desire-fulfillment”; for all particular objects of happiness, all the things people are (and in fact, can be) happy about, have in common that they consist of the realization of a state of affairs that fulfills a desire of the experiencing person.Footnote 9

What, then, is the formal object of pity? To recall, pity was analyzed as a form of displeasure caused by the belief that a state of affairs p obtains which is negative for another person and is undesired for altruistic reasons. This entails that all concrete objects of pity—all particular states of affairs that are and can be objects of pity, regardless of whether they consist of another’s loss of job, illness, lovesickness or whatever—have in common that they are, from the cognitive-motivational perspective of the emotion experiencer, present, negative, altruistically undesired states of affairs. To distill the formal object P E of an emotion E from the belief-desire analysis of E, one abstracts from the concrete objects of the emotion and characterizes them purely relationally, by referring to the emotion-defining beliefs and desires in which they figure. In this way, the description of the cognitive-motivational basis of an emotion can be packed into a description of the emotion’s object, which if nothing else allows to present the results of the belief-desire analysis of emotions in a succinct way (e.g., Lazarus 1991; Ortony et al. 1988; Reisenzein et al. 2003; Roberts 2003). Specifically, making use of the formal object of pity, pity for o because of p can be described as: unhappiness about a present state of affairs p that is negative for o and is altruistically undesired.

Because the analysis of pity by means of specifying a formal object is entailed by the belief-desire analysis, it adds at first sight nothing substantial to this analysis. A substantive difference between the belief-desire analysis of emotions and their analysis in terms of corresponding formal objects would arise, however, if one assumed that the formal object P E of an emotion E figures not only in the scientists’ description of the emotion, but also—in the form of concrete realizations P E (p)—as the intentional object of the person’s emotional experience of E; or at least as the object of a belief presupposed by E. This would mean that to experience pity for Karl, Maria must herself represent Karl’s job loss as a “present state of affairs that is negative for another, and is altruistically undesired.” According to CBDTE, this “formal object cognition” is not required to experience pity; certainly not as an explicit belief. One can say, however, that part of this cognition—the belief that Karl’s job loss is a present event that is negative for Karl—is implicitly present; for Maria believes indeed that Karl lost his job, and that Karl’s job loss is bad for him. However, the remaining part of the formal object cognition, the belief that Karl’s job loss is undesirable for Maria for altruistic reasons, need not be present for pity to occur according to CBDTE—neither explicitly nor implicitly. In contrast, the cognitive-evaluative theory of emotion (appraisal theory) seems to imply that, for an emotion to occur, the complete formal object cognition of that emotion must be present as an explicitly represented (although not necessarily conscious) belief. Inasmuch as this implication of appraisal theory is implausible, this is a good reason to be skeptical about it (see Reisenzein 2009a).

However, because CBDTE places no restrictions on the description of potential emotion-eliciting events in the language of thought, it does not exclude the possibility that an event is represented by the person herself as one that (partially) exemplifies the formal object property P E . Therefore, it is at least theoretically possible that Maria pities Karl (not only) for having lost his job, but (also) for the fact that something bad has occurred to him. According to CBDTE, to experience pity of this second kind, Maria must form the explicit belief that something bad has happened to Karl, as well as the explicit desire that this bad thing should not have occurred to him; for only if these explicit representations are available can the BDC access them and generate a feeling of displeasure. A possible example would be the following case: Maria is informed that “a bad thing has happened to Karl”, but does not yet know what the bad thing is. According to CBDTE, Maria should in this case first pity Karl that something bad has happened to him, and then—when she learns that Karl lost his job—pity him again for having lost his job.Footnote 10 Usually, however, the process of emotion generation works the other way round: Typically, Maria will first learn that a specific event has occurred (for example, that Karl was fired) and will only afterwards, if at all, construct a more abstract representation of this event, such as “something bad has happened to Karl.” However, if Maria forms this belief, she should not only feel pity for Karl because he lost his job, but also because something bad happened to him—even though these two feelings of pity are probably difficult to distinguish subjectively.

2.1.3 Does Pity Feel Special?

The result of the preceding analyses was that pity has a special cognitive-motivational background and as a consequence, a special formal object. I now turn to the emotion itself, the feeling of displeasure that pity is. The question I wish to discuss is: Does the feeling of pity, in addition to having distinct cognitive and motivational causes and a distinct formal object, also have a special phenomenal character? Does it feel a particular way to experience the mental pain that pity constitutes, a way that that differs from the feeling of egoistic unhappiness? I think something can indeed be said for this assumption.

The most direct argument for believing that pity is a qualitatively distinct kind of unpleasantness appeals to the evidence of introspection. This evidence suggests to me that pity does indeed feel different from egoistic suffering: It feels different, for example, to experience sorrow for Karl for losing his job, and to feel self-regarding unhappiness because of Karl’s job loss. However, it could be argued that even if one accepts this intuition, it is not clear that the difference in experiential quality between the two experiences is due to a difference in their hedonic tone. It might instead be due to differences in the phenomenal character of the beliefs and desires that cause these emotions, or of the action tendencies that they typically evoke (this objection presupposes that beliefs, desires and action tendencies do have phenomenal quality, which is controversial; see Reisenzein 2012a for more detail).Footnote 11 Or perhaps the special experiential quality of pity is due to other emotions that co-occur with pity, such as a feeling of caring for the other, that is absent in self-regarding unhappiness.

However, a more principled argument can be made. This argument focuses on the question of how we come to know that we experience pity about another’s fate, rather than self-regarding unhappiness (or some other emotion). To be sure, answering this question does not require to assume that the displeasure of pity has a special hedonic quality. Even if the hedonic feeling tones of pity and self-regarding unhappiness were exactly alike, we might still be able to infer that our emotion is pity from the context of the emotion—its causes and consequences (see Reisenzein and Junge 2012). However, if the proposed analysis of pity is correct, then this “inferential” account of emotion self-ascription assumes a lot: It assumes that, to know that one experiences pity, one must infer that the displeasure one feels about the negative fate of another was caused by the frustration of an altruistic desire, i.e. a desire for the welfare of the other not derived from egoistic motives. Likewise, to know that one experiences self-regarding sorrow, one must infer that the displeasure one feels was caused by the frustration of an egoistic desire. This surely demands too much: After all, many people (scientist and lay persons alike) are not even sure that altruistic desires exist! At this point, the idea that pity has a distinctive hedonic quality becomes attractive. If evolution thought it important to let humans know how they feel about another’s fate, beyond pleasure and pain—is the displeasure one feels when learning about another’s negative fate sorrow for the other, or just egoistic distress?—but at the same time had to make do with humans’ limited capacity for inference, metacognition, and insight into their motives, a natural solution would have been to arrange for it that altruistic and egoistic desires signal their fulfillment and frustration to consciousness by means of qualitatively distinct feelings of pleasure and pain.

The idea that there are several qualitatively distinct kinds of pleasure and pain is of course not new; it was championed by John Stuart Mill (1871; see also West 2004) and was defended, in the emerging academic psychology of emotion, by Wilhelm Wundt (1896) among others (see Reisenzein 2000). Wundt took the idea to its extremes, arguing, for example, that even the pleasurable feelings elicited by tasting sugar and those elicited by tasting mint are qualitatively distinct. For the present purposes, a much more moderate version of the pluralist theory of hedonic feelings will do, according to which different qualities of pleasure and displeasure are attached to the fulfillment and frustration of different basic motives (or even just some of them). According to this proposal, altruistic and egoistic motives in particular, give rise to distinct nonpropositional signals when the BDC detects that they have been fulfilled or frustrated. These signals are experienced as qualitatively distinct hedonic feelings; and these distinct feelings of pleasure and displeasure allow the person to distinguish between pity and other altruistic feelings (such as joy for the other, but also fear for the other and hope for the other) on the one hand, and self-regarding sorrow and other egoistic feelings (such as joy for oneself, fear for oneself, and hope for oneself) on the other hand. This distinction does not require awareness of the ultimate motives underlying altruistic versus egoistic feelings. What the person notices, however, is that for example the displeasurable feeling evoked by another’s fate comes in two different flavors, sorrow for herself, and sorrow for the other.

2.2 The Norm-Based Emotions: The Example of Guilt

Given the preceding, detailed analysis of pity, the analysis of guilt as the representative of the norm-based social emotions can be presented in a more succinct way. As implied by referring to this family of social emotions as norm-based, I follow tradition in assuming that they are reactions to perceived norm violations (e.g., guilt, indignation) and norm fulfillments (e.g., moral elevation) (see e.g., Ortony et al. 1988). I thus disagree with those authors who have claimed that guilt (and perhaps other norm-based emotions) can be experienced even in the absence of a perceived norm violation (see e.g., Wildt 1993). Although there are cases of guilt that prima facie seem to support this claim, such as the phenomenon of “survivor guilt” (guilt feelings of disaster survivors), I believe that these cases do not withstand scrutiny. Indeed, closer analysis suggests that even in these cases, a norm violation can be found for which experiencers blame themselves (see e.g., Jäger and Bartsch 2006). However, even if the assumption that guilt is always caused by a perceived norm violation should prove to be wrong, I take it to be largely undisputed that guilt is so caused in the standard cases. Any plausible theory of guilt must be able to explain these standard cases.

If CBDTE is also true for the norm-based emotions, then these emotions are in principle caused in the same way as self-regarding happiness and unhappiness. Specifically, negative norm-based emotions such as guilt are special forms of displeasure, unhappiness, or mental suffering that, like all negative emotions, are caused by the detection of a desire frustration by the BDC mechanism; whereas positive norm-based emotions such as moral satisfaction, like all positive emotions, arise if the BDC detects a desire fulfillment. As an example, let us assume that Maria (= a) has lied to her friend Berta (= A) and Maria now feels guilty about her action, the state of affairs Aa. According to CBDTE, the proximate causes of Maria’s guilt about Aa are her belief that she has lied to Berta (Aa), and her desire not to have lied to her (¬Aa). Maria’s BDC detects that the content of a newly acquired belief (Aa) is contrary to the content of one of Maria’s desires (¬Aa). As a consequence, the BDC generates a signal that represents the detected desire-incongruence, and that is experienced as a feeling of displeasure or mental pain.

However, analogous to the case of pity, this analysis is insufficient to individuate guilt as a distinct emotion, a separate form of mental suffering. Imagine that Maria is unhappy about having lied to Berta only because her lie turned out to have unfavorable consequences for her (she has brought herself in all sorts of predicaments with it), although Maria has no moral scruples whatsoever about having lied to Berta. In this case—my intuition tells me—Maria will regret (feel self-regarding sorrow) that she has lied to Berta; but she will not feel guilty about her action.

What, then, is special about the feeling of guilt; what is special about the unhappiness or mental suffering that it is? My proposal is analogous to the case of pity: What is unique about guilt is (at minimum) guilt’s special cognitive and motivational background. Specifically, I assume that (1) as highly social creatures (Richerson and Boyd 1998), humans also have desires and beliefs concerning the compliance of others, and themselves, with social and moral norms; and (2) guilt is experienced if one comes to believe that one has done something that conflicts with a behavioral norm, or rule of conduct, that one desires to obey for nonegoistic reasons.

Instead of developing the analysis of guilt step by step, as in the case of pity, I will present the result of this analysis first and comment on it afterwards.

CBDTE analysis of guilt: Guilt about p is a form of displeasure (or suffering, mental pain) that person a experiences if:

-

1a.

a believes that p; with p = Aa, where Aa is the performance of an action of type A by a; and

-

1b.

a desires ¬Aa (that s/he had not performed the action A).

-

2.

a’s the desire for ¬Aa is based on:

-

2a.

a’s belief that a is an actor of type T and a is in situation of type S; and

-

2b.

a’s desire that in situations of type S, actors of type T do not perform actions of type A.

-

2a.

-

3.

The desire 2b (the desire for rule compliance) is based on:

-

3a.

a’s belief that in situations of type S, actions of type A are forbidden for actors of type T by a norm-setting agent P; and

-

3b.

a’s desire that the commandments and prohibitions of P (in general, or at least in this specific case) be obeyed.

-

3a.

-

4.

The desire 3b (that the commandments and prohibitions of P be obeyed) is not based on egoistic motives.

In our example, therefore, Maria’s desire to not lie to Bertha (1b) is derived from her desire to obey a particular behavioral norm (2b). The contents of norms can generally be described as behavior rules of the form “In situation of type S, actors of type T should (not) perform actions of type A” (e.g., Siegwart 2010). In our example, the relevant rule of conduct can be formulated as “one ought not lie to a friend without need”; or in more detail: “if one communicates with another person who is a friend and there is no important reason for lying, then one should not lie to the other”. From Maria’s desire (2b) that this rule should be adhered to (that actors of type T do not perform actions of type A in situations of type S) and her belief (2a) that she is in a situation of type S (a communication situation in which there is no important reason to lie) and that she is an actor of type T (she is a friend of Berta, who communicates something to her), one can derive Maria’s specific desire not to lie to Berta in this situation (1b).

One must ask further, however, where Maria’s desire to obey the truth-telling norm (2b) stems from. I propose that Maria’s desire to respect this norm is derived from (3a) Maria’s belief that the behavior (not to lie to a friend) was commanded by a norm-setting agent P, and (3b) Maria’s desire to obey the commandments of this authority—either in general, or at least in this specific case. The perceived norm-setting agent can be a single person, a group, society, or a superhuman (god) and even an abstract entity (“the world order”).

The proposed derivation of Maria’s desire (2b) from (3a) and (3b) is an explication of the process of norm internalization or norm acceptance. It corresponds essentially to a proposal by Conte and Castelfranchi (1995) in cognitive science and to similar views endorsed by a number of psychologists (e.g., Ajzen 1985) and sociologists (e.g., Hart 1994). According to this view, to internalize, or accept, a norm requires not only to cognize the norm, i.e. to come to believe that it exists (3a); it also requires to “import” the prescribed action rule into one’s motivational system; or in other words, to acquire the desire that the rule be followed (2b). According to the proposed explication of norm internalization, this desire is, like other nonbasic desires, created by deriving it from a more fundamental desire; this case, the desire to obey the commandments of a norm-setting agent P (3b). For example, the internalization of the commandment “One ought not lie to a friend without need” by Maria occurs as follows: First, Maria comes to believe (3a) that this commandment exists, i.e. that the compliance with the rule of action, “do not lie to a friend without need” is required by some norm-setting agent P (e.g., her parents). Because Maria wishes that the commandments of P are obeyed (3b), she acquires the derived desire to obey the truth-telling norm (2b). It may be noted that the belief-desire theory of emotions provides additional support for this “motivational” analysis of norm internalization; for according to the theory, a breach or fulfillment of a norm can cause emotional reactions only if the norm has been accepted in this motivational sense.

Baurmann (2010) has proposed to differentiate the desire to abide by a social or moral norm into two components: the wish that others follow the behavior rule that is the content of the norm, and the wish that oneself follows it. In the CBDTE analysis of the norm-based emotions, this distinction is represented by specifying whether or not the person counts herself to the group of actors for which the action is commanded. To experience guilt, the latter is required (2a); for if Maria does not count herself among the people addressed by the norm “do not perform A in S”, then the desire for ¬Aa cannot be derived from her belief that she has performed A, and her desire that the norm is obeyed. Even then, however, Maria should still be emotionally upset (e.g., indignant) about the norm-violating actions of other actors b who, in her opinion, are addressed by the norm. The reason is that, for these actors, the necessary derived desire Des(¬Ab) can be computed. For example, most citizens desire and expect that their garbage bins are regularly emptied by the professional garbage collectors, but not by themselves. Consequently, they won’t feel guilty if they do not empty their garbage bins, but will be angry if the professionals don’t.

Finally, I assume—in analogy to the analysis of pity—that the desire 3b (that the commandments of the norm-setting agent P be followed) is not egoistically motivated. If one wants to obey a commandment of a norm-setting agent only out of selfish interests, for example to gain reputation or to avoid sanctions, then—my intuition tells me—one may experience regret about having performed a norm-violating action; but one will not feel guilty about it. The desire to follow the commandment of the norm-setting agent could be derived from altruistic desires, or it could be based on the adoption of a group or “we” perspective (Bacharach 2006; Tuomela 2000), resulting in a desire for the welfare of one’s group, or “us”, which I take to be not entirely egoistic also (since the group includes others in addition to oneself). Finally, Maria’s desire to obey the truth-telling norm could be based on a disposition (possibly innate) to accept norms that she considers valid in themselves, independent of any specific norm-setting agent (Heider 1958; see also, Conte and Castelfranchi 1995).Footnote 12

As in the case of pity, an alternative analysis of guilt is possible that makes use of the concept of the formal object of guilt. According to this alternative analysis, guilt is displeasure about the violation of a behavior rule that is, at least in part, accepted (i.e., whose observance is desired) for nonegoistic reasons.

The proposed belief-desire analysis of guilt deliberately leaves out two factors that need to be considered in a complete analysis. The first of these concerns the role played by the effects of norm-violating actions for the intensity of guilt: Other factors constant, the intensity of guilt about a norm-violating action is typically greater, the more harm it caused to others. For example, Maria will typically feel more guilt about having lied to Berta if her lie has serious negative consequences for Berta, than if it has only mild or no negative consequences. This can be explained by assuming that in the former case, Maria feels strictly speaking not only guilty about having violated one accepted norm (“do not lie”) but also about having violated another norm (“do not cause harm to others”). This proposal is supported by the consideration that if Maria does not regard herself as responsible for the harm caused to Berta (e.g., because it was unforeseeable by her), her guilt will be mitigated. This brings me to the second factor neglected in the proposed analysis of guilt, “perceived responsibility” (cf. Lorini and Schwarzentruber 2011; Ortony et al. 1988; Weiner 2006; actually this factor is also important for pity; see Weiner 2006). In my analysis, I assumed implicitly that the agent held himself responsible for the norm-violating action. One way of how perceived responsibility could be explicitly incorporated into the proposed analysis of guilt is the following: Responsibility modifies the degree to which the person sees herself or others as actors who are addressed by a particular norm.

2.3 On the Functions of the Social Emotions

What are the evolutionary functions of the social emotions, their adaptive benefits? Following a common practice in emotion psychology, I distinguish between “organismic” (system-internal) and social-communicative functions of emotions. According to CBDTE, the organismic function of emotions in general is to signal matches and mismatches between newly acquired beliefs on the one hand, and existing beliefs and desires on the other hand, to other cognitive subsystems, to thereby globally prepare the agent to deal with them in a flexible and intelligent way. The social emotions fit into this picture well, as can again be seen by considering pity and guilt: According to the proposed analysis, pity signals the frustration of an altruistic desire by another’s negative fate; whereas guilt signals the frustration, by an own action, of a nonegoistic desire to comply with a norm. I assume it is important to become immediately and distinctly aware of these changes in the belief-desire system whenever they occur. Simultaneous with the experience of the unpleasant feelings, the person’s attention is automatically drawn to the emotion-evoking events—the negative fate of the other in the case of pity, and the own deviant action in the case of guilt—thereby enabling and preparing the conscious analysis of these events, their causes and consequences (Reisenzein 2009a).

Pity and guilt typically evoke action tendencies to change the eliciting situations—for example to help the other in the case of pity, or to make an attempt to repair an inflicted damage in the case of guilt. According to a number of authors (e.g., Weiner 2006), these action desires are generated by the respective emotions in a direct, nonhedonistic way (see Reisenzein 1996). This assumption is also adopted in CBDTE. In addition, however, it is assumed that the experience of the unpleasant feelings of pity and guilt may reinforce the person’s action motivation, by generating hedonistic motives to reduce the unpleasant feelings (Reisenzein 2009a). In CBDTE, the hedonistic mechanism is hence regarded as a motivational support mechanism: a mechanism that reinforces the motivation to satisfy the original desire that p, when it is threatened or frustrated, by creating an auxiliary desire to reduce or abolish the displeasure caused by a threat to, or a frustration of, the primary desire. In this way, the secondary, hedonistic desire reinforces the primary desire even though it is, in and of itself, blind to the aim of the primary desire. In addition, specifically in the case of guilt, anticipatory feelings experienced if one vividly imagines a possible rule violation—which presumably engages the emotion mechanisms in a “simulation mode” (Reisenzein 2012b)—can prevent a norm violation from occurring in the first place. The helping and rule-abiding actions caused by pity and guilt, respectively, presumably increase the reproductive chances of individuals or (if one accepts the possibility of group selection; see Richerson and Boyd 2005) those of social groups (see also below).

In addition to their system-internal functions, emotions are frequently assumed to have social-communicative functions: adaptive benefits that accrue from the involuntary (and perhaps also the voluntary) signalling of emotions to others. According to CBDTE, paralleling the system-internal function of emotions, the verbal or nonverbal communication of emotions to other agents informs them about the occurrence of a belief-belief or belief-desire match or mismatch in the communicating agent. Thereby, communicated emotions alert others simultaneously to two changes: (a) The agent acquired a new belief that matched or mismatched a pre-existing belief or desire; and (b) something may have occurred in the world that caused this agent to experience a belief-belief or belief-desire match or mismatch (Reisenzein and Junge 2012). It is easy to see how this information could be useful for other agents: It allows them to update their mental model of the emotion experiencer, or of the environment, and thereby to better adapt to either.

However, what are the adaptive benefits of communicating social (and other) emotions for the communicator? At first sight, there seem to be only disadvantages: By communicating his or her emotions to others, the agent becomes more predictable and thus exploitable by others, and gives away potentially useful information about the environment for free. The readiness to (truthfully) communicate emotions, if it exists at all, is therefore a form of biological altruism. As such, it would have required special evolutionary conditions to emerge. Possible evolutionary scenarios are kin selection, reciprocal altruism, group selection (Richerson and Boyd 2005), and costly signalling (Dessalles 2007). My own bet with respect to the social emotions is the group selection scenario. Even though it may not usually be of advantage for an individual to reveal his emotions and thereby the underlying desires to others, I submit the hypothesis that groups in which emotions, in particular social emotions, are truthfully communicated, are at an advantage over groups in which emotions are hidden or faked. The signalling of social emotions may therefore have been selected as a truthful sign of other’s group-centered concerns: Their altruistic concern for others, and their true caring for the observance of the social norms of the group. In showing pity for Karl about his job loss, Maria reveals to Karl and to others that Karl’s fate is “genuinely” (that is, according to the proposed analysis, not just for selfish reasons) dear to her heart; and in showing guilt about having lied to Berta, Maria reveals to Berta and others that she “truly” cares about the social norm that she violated (that is, she wants to obey the norm not only for selfish reasons), and is therefore a particularly reliable adherent of the group norms. Hence, the social-communicative function of the social emotions is to reveal others’ social (nonegoistic) desires. This function is in my view central to understanding the role that emotions play for the stabilization of social order.

Notes

- 1.

Specifically, emotions in CBDTE are conceptualized as nonpropositional signals that are subjectively experienced as feelings of, in particular, pleasure and displeasure, surprise and expectancy confirmation, and hope and fear (see the next section, and Reisenzein 2009a).

- 2.

I consider these intuitions to be the results of mental simulations of situations that elicit social emotions, and therefore accord them empirical status, although my simulations are limited by being single-case experiments. However, some of the simulation results reported for pity have been replicated in larger samples using hypothetical scenarios (Reisenzein 2002). In any case, readers are invited to join in the described mental simulations.

- 3.

In this example, the object of pity is a social event involving the other (Karl’s job loss). However, in general the object of pity can be any state of affairs involving another agent: His social or physical condition, his mental states (beliefs, desires, emotions), and his actions.

- 4.

According to CBDTE, this feeling, like all emotions, is in itself not object-directed; it has no propositional content (Reisenzein 2009a). However, CBDTE assumes that, as a result of being processed by subsequent cognitive processes, the feelings generated by the emotion mechanisms are usually linked to the propositional objects of their causative beliefs, giving rise to the subjective impression that the feelings are directed at these objects (see Reisenzein 2009a, 2012a). In our example, Maria’s feeling of displeasure is linked to Fo; as a result, it appears to Maria that she feels sorry about Fo. Presupposing this understanding of object-directedness, it is unproblematic to speak about the intentional object of pity and other emotions in CBDTE.

- 5.

The existence of a special grammatical construction (the feeling-for construction) in ordinary language to describe other-regarding emotions (e.g., feeling sorry for, fearing for, hoping for, being angry for someone) indicates that the distinction between self- and other-regarding feelings is salient and important in common-sense psychology.

- 6.

The derivation of desires from other desires can occur by means of conscious reasoning processes, that is by reflecting about one’s desires and possible means to satisfy them; however, the most basic mechanism of desire-derivation consists presumably of a hardwired procedure that automatically generates a derived desire for p 1 whenever a more basic desire Des(p 2) and a fitting means-ends belief Bel(p 1 → p 2) are present (see also, Conte and Castelfranchi 1995).

- 7.

In the Rhetoric, Aristotle defines friendship as wanting good things for another for his sake and not for one’s own. See Cooper (1977).

- 8.

The derivation of the concrete desire that proximately causes pity often occurs only at the time when pity is experienced, because this derivation is often occasioned by becoming aware of the event that elicits pity. However, the derivation of this desire can of course take place earlier, analogous to the case of Maria’s happiness about Schroiber’s election victory. For example, Maria could have formed the (explicit) desire that Karl should not lose his job when she heard about upcoming personnel cuts. When she later heard about Karl’s job loss, that desire only had to be retrieved from long-term-memory.

- 9.

Roberts (2003, p. 110) speaks of the “defining proposition” of an emotion. In psychology, the appraisal theorist R. S. Lazarus (1991) has coined the very similar concept of “core relational theme”. According to Lazarus, every emotion (happiness, sadness, fear and so on) is characterized by a unique core relational theme, which describes what is common to the different specific events that elicit the respective emotion. For example (and differing somewhat from the belief-desire analysis of happiness proposed here), the core relational theme of happiness is “making reasonable progress toward the realization of a goal” (Lazarus 1991, p. 122).

- 10.

Maria’s intensity of pity may however be reduced in the first case, as she does not know exactly how bad the bad thing is that happened to Karl. Furthermore, because of the epistemic uncertainty present in this case, fear may predominate.

- 11.

To avoid this objection, while still granting partial correctness to the idea that beliefs and desires contribute to phenomenal quality, one could argue that the same pleasure signal feels different if it occurs in different cognitive-motivational contexts (see also Reisenzein 2012a).

- 12.

Such “objective” norms might be understood as norms that the person believes would be commanded for a human society by an ideal (roughly: a fully informed, fully rational, impartial and benevolent) norm-setting agent.

References

Adam, C., A. Herzig, and D. Longin. 2009. A logical formalization of the OCC theory of emotions. Synthese 168: 201–248.

Ajzen, I. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior, ed. J. Kuhl and J. Beckmann, 11–39. Berlin: Springer.

Arnold, M.B. 1960. Emotion and personality, vol. 1 & 2. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bacharach, M. 2006. In Beyond individual choice: Teams and frames in game theory, ed. N. Gold and R. Sudgen. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Batson, C.D., and L.L. Shaw. 1991. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry 2: 107–122.

Baurmann, M. 2010. Normativität als soziale Tatsache. H. L. A. Harts Theorie des “internal point of view” [Normativity as a social fact. H. L. A. Hart’s theory of the “internal point of view”. In Regel, Norm, Gesetz. Eine interdiziplinäre Bestandsaufnahme [Rule, norm, law. An interdisciplinary survey], ed. M. Iorio and R. Reisenzein, 151–177. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag.

Castelfranchi, C., and M. Miceli. 2009. The cognitive-motivational compound of emotional experience. Emotion Review 1: 223–231.

Conte, R., and C. Castelfranchi. 1995. Cognitive and social action. London: UCL Press.

Cooper, J.M. 1977. Aristotle on the forms of friendship. Review of Metaphysics 30: 619–648.

Davis, W. 1981. A theory of happiness. Philosophical Studies 39: 305–317.

De Sousa, R. 1987. The rationality of emotions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dennett, D.C. 1971. Intentional systems. Journal of Philosophy 68: 87–106.

Dessalles, J.-L. 2007. Why we talk: The evolutionary origins of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ekman, P. 1992. An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion 6: 169–200.

Ellsworth, P.C., and K.R. Scherer. 2003. Appraisal processes in emotion. In Handbook of affective sciences, ed. R.J. Davidson, K.R. Scherer, and H.H. Goldsmith, 572–595. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fodor, J.A. 1975. The language of thought. New York: Crowell.

Fodor, J.A. 1987. Psychosemantics: The problem of meaning in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Frijda, N.H. 1986. The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldie, P. 2007. Emotion. Philosophy Compass 2: 928–938.

Green, O.H. 1992. The emotions: A philosophical theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Hart, H.L.A. 1994. The concept of law. Oxford: Clarendon.

Heider, F. 1958. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Jäger, C., and A. Bartsch. 2006. Meta-emotions. Grazer Philosophische Studien 73: 179–204.

Kenny, A. 1963. Action, emotion, and will. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Lazarus, R.S. 1991. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lorini, E., and F. Schwarzentruber. 2011. A logic for reasoning about counterfactual emotions. Artificial Intelligence 175: 814–847.

Marks, J. 1982. A theory of emotion. Philosophical Studies 42: 227–242.

McDougall, W. 1908/1960. An introduction to social psychology. London: Methuen.

Meinong, A. 1894. Psychologisch-ethische Untersuchungen zur Werth-Theorie [Psychological-ethical investigations in value theory]. Graz: Leuschner & Lubensky. Reprinted in R. Haller & R. Kindinger (Eds.) (1968). Alexius Meinong Gesamtausgabe [Alexius’ Meinong’s complete works] (Vol 3, pp. 3–244). Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt.

Miceli, M., and C. Castelfranchi. 1997. Basic principles of psychic suffering: A preliminary account. Theory & Psychology 7: 769–798.

Mill, J.S. 1871/2001. In: Utilitarianism, ed. R. Crisp. Oxford: Oxford University press.

Nussbaum, M.C. 2001. Upheavals of thought: The intelligence of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oatley, K. 2009. Communications to self and others: Emotional experience and its skills. Emotion Review 1: 206–213.

Ortony, A., G.L. Clore, and A. Collins. 1988. The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reisenzein, R. 1996. Emotional action generation. In Processes of the molar regulation of behavior, ed. W. Battmann and S. Dutke, 151–165. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Reisenzein, R. 2001. Appraisal processes conceptualized from a schema-theoretic perspective: Contributions to a process analysis of emotions. In Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research, ed. K.R. Scherer, A. Schorr, and T. Johnstone, 187–201. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reisenzein, R. 2002. Die kognitiven und motivationalen Grundlagen der Empathie-Emotionen. [Cognitive and motivational foundations of the empathic emotions]. Talk delivered at the 43rd Congress of the German Association of Psychologists (DGPs) in Berlin, 2002.

Reisenzein, R. 2006a. Arnold’s theory of emotion in historical perspective. Cognition and Emotion 20: 920–951.

Reisenzein, R. 2006b. Motivation [Motivation]. In Handbuch Psychologie [Handbook of psychology], ed. K. Pawlik, 239–247. Berlin: Springer.

Reisenzein, R. 2007. What is a definition of emotion? And are emotions mental-behavioral processes? Social Science Information 46: 424–428.

Reisenzein, R. 2009a. Emotions as metarepresentational states of mind: Naturalizing the belief-desire theory of emotion. Cognitive Systems Research 10: 6–20.

Reisenzein, R. 2009b. Emotional experience in the computational belief-desire theory of emotion. Emotion Review 1: 214–222.

Reisenzein, R. 2010. Moralische Gefühle aus der Sicht der kognitiv-motivationalen Theorie der Emotion [Moral emotions from the perspective of the cognitive-motivational theory of emotion]. In Regel, Norm, Gesetz. Eine interdiziplinäre Bestandsaufnahme [Rule, norm, law. An interdisciplinary survey], ed. M. Iorio, and R. Reisenzein, 257–283. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag.

Reisenzein, R. 2012a. What is an emotion in the Belief-Desire Theory of emotion? In The goals of cognition. Essays in honor of Cristiano Castelfranchi, ed. F. Paglieri, L. Tummolini, R. Falcone, and M. Miceli, 181–211. London: College Publications.

Reisenzein, R. 2012b. Fantasiegefühle aus der Sicht der kognitiv-motivationalen Theorie der Emotion [Fantasy emotions from the perspective of the cognitive-motivational theory of emotion]. In Emotionen in Literatur und Film [Emotions in literature and film], ed. S. Poppe, 31–63. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

Reisenzein, R. 2012c. Extending the belief-desire theory of emotions to fantasy emotions. Proceedings of the ICCM 2012: 313–314.

Reisenzein, R., and S. Döring. 2009. Ten perspectives on emotional experience: Introduction to the special issue. Emotion Review 1: 195–205.

Reisenzein, R., and M. Junge. 2012. Language and emotion from the perspective of the computational belief-desire theory of emotion. In Dynamicity in emotion concepts (Lodz Studies in Language, 27, 37–59), ed. P.A. Wilson. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Reisenzein, R., W.-U. Meyer, and A. Schützwohl. 2003. Einführung in die Emotionspychologie, Band III: Kognitive Emotionstheorien [Introduction to emotion psychology, Vol 3: Cognitive emotion theories]. Bern: Huber.

Reisenzein, R., E. Hudlicka, M. Dastani, J. Gratch, E. Lorini, K. Hindriks, and J.-J. Meyer. 2013. Computational modeling of emotion: Towards improving the inter- and intradisciplinary exchange. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 4: 246–266. doi:http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/T-AFFC.2013.14

Reiss, S. 2004. Multifaceted nature of intrinsic motivation: The theory of 16 basic desires. Review of General Psychology 8: 179–193. New York: Tarcher Putnam.

Richerson, P., and R. Boyd. 1998. The evolution of ultrasociality. In Indoctrinability, ideology and warfare, ed. I. Eibl-Eibesfeldt and F.K. Salter, 71–96. New York: Berghahn Books.

Richerson, P.J., and R. Boyd. 2005. Not by genes alone. How culture transformed human evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roberts, R.C. 2003. Emotions: An essay in aid of moral psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roseman, I.J. 1979, September. Cognitive aspects of emotions and emotional behavior. Paper presented at the 87th annual convention of the APA, New York City.

Scherer, K.R. 2001. Appraisal considered as a process of multilevel sequential checking. In Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research, ed. K.R. Scherer, A. Schorr, and T. Johnstone, 92–129. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Searle, J. 1983. Intentionality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Siegwart, G. 2010. Agent – Situation – Modus – Handlung. Erläuterungen zu den Komponenten von Regeln. [Agent – situation – mode – action. Comments on the components of rules]. In Regel, Norm, Gesetz. Eine interdiziplinäre Bestandsaufnahme [Rule, norm, law. An interdisciplinary survey], ed. M. Iorio, and R. Reisenzein, 23–45. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag.

Sloman, A. 1992. Prolegomena to a theory of communication and affect. In Communication from an artificial intelligence perspective: Theoretical and applied issues, ed. A. Ortony, J. Slack, and O. Stock, 229–260. Heidelberg: Springer.

Smith, A. 1759. The theory of moral sentiments. London: A. Millar.

Smith, M.A. 1994. The moral problem. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sober, E., and D.S. Wilson. 1998. Onto others. The evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Solomon, R.C. 1976. The passions. Garden City: Anchor Press/Doubleday.