Abstract

This chapter deals with current issues and policies regarding the updated developments of the three crises dealt with in this book: in Argentina, USA, and Europe. Argentina restructured its debt in 2005 with a significant reduction, which was accepted by 76 % of the creditors and resumed payment to them. In 2010 a second debt swap was offered which was accepted by another 17 % of the creditors. Anyway the terms of the debt exchanges left some open questions. In the USA the consequences of the Dodd–Frank Act are analyzed. Finally, in the EMU, a near-defaulting situation for Greece still remains unsolved, while the recent quantitative easing monetary policy implemented by the ECB succeeded to calm financial markets and created the right environment necessary to promote a new European economic recovery.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In this chapter we illustrate the more recent problems that characterize the economic and financial situation of the three geographical areas we have dealt with in this book: Argentina, the USA, and Europe. Our analysis is updated until May 2015, and our focus is pointed on current issues and policies promoted in each of these areas, with a special emphasis toward the open problems that still remain unsolved.

The chapter is organized as follows. In Sect. 11.2, the case of Argentina’s new debt restructuring in 2005 and again in 2010 is dealt with. Section 11.3 is devoted to an evaluation of the Dodd–Frank Act in the US, and to the need for a global lender of last resort. Section 11.4 deals with current issues and unsolved problems in Europe, particularly in the Eurozone.

Among these, in Sect. 11.4.1 we analyze the EMU’s crisis-hit countries assistance programs, while in Sect. 11.4.2 the unsuccessful results of the first two assistance programs in Greece are dealt with. In Sect. 11.4.3 we illustrate some remaining EMU’s institutional matters. We also discuss if the ECB can assume the role of lender of last resort for the sovereign debts in Sect. 11.4.4 and the recent quantitative easing monetary policy implemented by the ECB in Sect. 11.4.5. Finally, in Sect. 11.4.6 we conclude with an assessment of the legacy of the Eurosystem crisis.

Anticipating the main conclusion, we share the view that the resilience of the Eurozone in the long run depends on the continuing process of political unification, which must proceed hand in hand with the creation of a fiscal union. Such a political unification is needed because the Eurozone has dramatically weakened the power and legitimacy of member states’ governments and left a vacuum in their place instead of creating a supranational government.

This would also imply the creation of a supranational fiscal risk-sharing mechanism that could insure European countries against very severe downturns like that caused by the Great Crisis.

2 Argentina: The New 2014 Default

In 2005 Argentina restructured its debt with a significant reduction which was accepted by 76 % of the creditors and resumed payment to them. In 2010 a second debt swap was offered which was accepted by another 17 % of the creditors. So, only 7 % of the bondholders rejected the terms of the debt exchanges, among them the so-called vulture funds.

Between 2009 and 2011, two of them—NML Capital and Aurelius—together with other individual holdouts, sued in federal court in New York for full payment of 1.3 billion dollars in Argentine bonds that had acquired in 2008 at 20–30 % of their nominal value.

The district judge Thomas P. Griesa ruled that Argentina could not pay the creditors who had accepted its restructuring until it fully paid—including past interest—those who had rejected it. According to him, the country could not pay only those who cooperated with the 2005 and 2010 restructurings and ignore the rest.

However, if Argentina paid 100 % of what the holdouts were owed in principal and accrued interest, as the district court ruled, the bondholders who agreed to the 2005 and 2010 restructurings could invoke the “most favored creditor clause” included in the debt exchange contract and demand the same treatment. This amounted more than USD100 billion—Argentina’s Central Bank reserves totaled at that time only USD29 billion. So, in practical terms, the ruling became of impossible compliance until December 31, 2014, when the “most favored creditor clause” expired.

Many lawyers considered that the ruling was surprisingly harsh, marking the first time a US judge had issued such an injunction based on a peculiar interpretation of the so-called “pari passu” clause that states that all bondholders must be treated equally. In this case, the clause has been interpreted by the court as meaning that a debtor cannot make individual payments on a loan unless it is current on all payments under that loan. In an open letter to the US Congress, 100 international economists warned that the ruling “can torpedo an existing agreement with those bondholders who chose to negotiate”, thus threatening future debt restructurings.

The US judicial ruling that the holdouts must be paid before bondholders forced Argentina to miss bond payments on July 30, 2014. Although Argentina transferred the payment in question, the US judge ordered the Bank of New York Mellon not to transfer the money to the creditors. This in turn caused Argentina to be declared in selective default by Standard & Poor’s and in restricted default by Fitch. Both terms indicate that Argentina had defaulted on one or more of its financial commitments but continues to meet others.

The US court ruling pushed Argentina to a new default on its total public debt. In fact, the judge blocked any payment to bondholders unless the country also paid to the vulture funds favored by his ruling. It was expected this default to be a short one. As of January 1, 2015, an arrangement would be more likely to be made once the “most favored creditor” clause expired. In the meantime it aggravated the country’s already bad economic situation.

The default meant that in spite of settling the ICSID arbitral awards against the country which remained unpaid, reaching an agreement to pay Repsol for the expropriation of YPF and with the Paris Club on outstanding debt, Argentina still had no access to international capital markets it badly needed.

After growing by an average of 5.6 % from 2005 to 2013, the rate of growth was negative in 2014. Commercial credit lines were cut off, investment dropped, and access to dollars was further strangled, which will unleash new restrictions on imports. Of course, this was not the sole result of the default. It only worsened existing problems: an increasing use of the inflation tax by the government, growing macroeconomic imbalances and exchange and trade controls which have long made it hard to get hold of primary materials, and stifling production.

However, the fact that less than 1 % of the creditors can put at risk an agreement settled with 93 % of the bondholders calls for international action on this issue.

A Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism is badly needed to avoid this situation to repeat in the future. Another alternative is the creation of a forum for debt renegotiation, along the lines of the Paris Club (for long-term, bilateral government debt of poor countries) and the London Club (for debt owed to banks). A first step in this direction has been for developing countries to include collective action clauses (CACs) into sovereign bond contracts. This clause allows a supermajority of bondholders to agree to a debt restructuring that is legally binding on all holders of the bond, including those who vote against the restructuring.Footnote 1

3 The USA After the 2007–2009 Crisis

3.1 The Dodd–Frank Act

In the USA, one of the main lessons taught by the crisis was the existence of misaligned economic incentives within mortgage securitization transactions as well as the financial system in general. Some steps were taken after 2008 to correct this situation. We list below six of these misalignments and mention the measures (in italics) already taken by the Dodd–Frank Act in order to deal with each of them.Footnote 2

A comment on their limitations is included. A reference is also made to the compensation policies and the need to align them with the goal of avoiding excessive risk taking by financial institutions. Some additional pending issues are briefly mentioned in the following points:

-

1.

The originators and securitizers seldom retained meaningful “skin in the game”. These market participants received immediate profits with each deal while assuming that they faced little or no risk of loss if the loans defaulted. As a result, securitizers had very little incentive to maintain adequate lending and servicing standards. Moreover, an active market arose in selling and repackaging equity tranches in collateralized debt obligations, thereby removing all risk of loss from the original security issuer.

The Dodd–Frank Act, passed in 2010, requires security issuers to retain no less than 5 % of the equity risk, so they have an incentive to more carefully choose the mortgages and other assets they include in the pool. However, asset-backed securities that are collateralized exclusively by residential mortgages that qualify as “Qualified Residential Mortgages” are exempted.

-

2.

Since the servicers of securitized mortgages do not own the mortgages, they lack economic incentives to mitigate losses through effective loan restructuring.

The Dodd–Frank Act called for banks to retain at least 5 % of the risk in the loans they originate. However, the so-called Qualified Residential Mortgages are exempted from this requisite.

-

3.

Risk migrated into the so-called shadow banking system. For banks, once loans were securitized, they were off the balance sheet and no longer on the radar of many banks and bank regulators.

The Dodd–Frank Act made provisions which go some way toward regulating the shadow banking system by stipulating that the Federal Reserve System would have the power to regulate all institutions of systemic importance. However, the 75 trillion global shadow banking system still remains mostly unregulated.

-

4.

Lack of effective market discipline due to “too big to fail”. Policymakers in several instances resorted to bailouts instead of letting these firms collapse into bankruptcy because they feared that the losses generated in a failure would cascade through the financial system, freezing financial markets and stopping the economy in its tracks. These fears were realized when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy.

With the benefit of this implicit safety net, these big institutions have been insulated from the normal discipline of the marketplace that applies to smaller banks and practically every other private company. This poses a moral hazard issue which has to be tackled by way of regulation.

The Dodd–Frank Act created the Federal Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), chaired by the Treasury Secretary and made up of the other financial regulatory agencies, which is responsible for designating systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). SIFIs are subject to heightened supervision and higher capital requirements. They are also required to maintain resolution plans and could be required to restructure their operations if they cannot demonstrate that they are resolvable.

Banking companies with over $50 billion in assets are automatically considered SIFIs. Additionally the Dodd–Frank Act gives FSOC the authority to design as SIFI any nonbanking financial company that could pose a threat to the financial stability of the USA.

The Dodd–Frank Act creates a new resolution authority for large financial institutions whose failure could threaten the US economy. This Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA) replaces bankruptcies for affected financial institutions. The OLA strictly prohibits bailouts. It is expected that with bailout off the table, management will have a greater incentive to bring in an acquirer or new investors before failure, and shareholders and creditors will have more incentive to go along with such a plan in order to salvage the value of their claims.

However, as the former FDIC’s Chairman Sheila Bair (2011) warned, the tools provided by the Dodd–Frank Act will be effective only if regulators show the courage to fully exercise their authorities under the law. Unfortunately, the past experience shows that regulators acted too late, or with too little conviction, when they failed to use authorities they already had or failed to ask for the authorities they needed to fulfill their mission (ibid).

-

5.

Insufficient capital standards. At the height of the crisis, the large financial institutions had too little capital to maintain market confidence in their solvency.

The international Basel III agreement and Section 171—the Collins Amendment—of the Dodd Frank Act have increased the amount of bank capital with the purpose of ensuring that banks will be able to withstand future downturns.

Experience will show if these levels are enough to keep financial institutions safe and avoid bank runs in the future.

-

6.

Failures of the credit rating agencies. They were an essential input into the process of manufacturing vast quantities of triple-rated securities with attractive yields which turned out to be highly risky assets.

The Dodd–Frank Act imposes a new regulatory scheme on rating agencies. It mainly directs the SEC to issue rules implementing the law and authorizes various studies of issues related to credit ratings. In August 2014, the SEC adopted new requirements for credit rating agencies. The new requirements address internal controls, conflicts of interest, disclosure of credit rating performance statistics, procedures to protect the integrity and transparency of rating methodologies, disclosures to promote the transparency of credit ratings, and standards for training, experience, and competence of credit analysts.

Time will tell if these reforms are enough to keep credit rate agencies transparent and free of conflicts of interest. In principle, they not seem to be enough to deal with such a big challenge. Excessive risk taking by financial institutions was a factor that significantly contributed to the incubation of the crisis. Compensation policies can play a useful role in reducing excessive risk taking.

In this respect, there are very interesting proposals by the president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, William C. Dudley. He argues that a well-designed compensation structure can help favorably tip the balance between maximizing benefits and risk taking by effectively extending the time horizon of senior management and material risk takers and by forcing them to more fully internalize the consequences of their actions. For example, as long as deferred compensation is set at a horizon longer than the life of the trade, this can ensure the firm’s and the trader’s incentives are aligned (Dudley 2014).

However, as Dudley argues, given that unethical and illegal behavior may take a much longer period of time to surface, a decade would seem to be a reasonable timeframe to provide sufficient time and space for any illegal actions or violations of the firm’s culture to materialize and fines and legal penalties realized. The goal should be to incent senior management and the material risk takers to focus on maximizing the long-term “enterprise” value of the firm, not just the short-term share price. One mechanism which can contribute to this goal is to increase the relative size of the debt component of deferred compensation as one moves up the management ranks to the senior managers of the firm (ibid).

Dudley also proposes that a sizeable portion of a fine should be paid for out of the firm’s deferred debt compensation. In other words, in the case of a large fine, the senior management and the material risk takers would forfeit their performance bond. This would increase the financial incentive of those individuals who are best placed to identify bad activities at an early stage or prevent them from occurring in the first place.

3.2 The Need for a Global Lender of Last Resort and the Interest Rate Risk

As we have seen in Chap. 3, the 2007–2009 crisis did not begin in the traditional banking system but instead was centered in the new shadow banking system. This was a quite unregulated system. The Group of Thirty has advanced some proposals to regulate the money market mutual funds, which compete with depository banks without being subject to any prudential regulation (Group of Thirty 2009).

Although money market funding is global, the collapse of shadow banking onto the traditional banking system was local, depending on which particular nationally domiciled bank had the responsibility of rolling over the money market funding of a given shadow banking entity (Mehrling 2014).

As the funding of the global shadow banking system was reliant on the Eurodollar market, the question of a global lender of last resort was really a question about backstop for that market. The decision in October 2013 to establish permanent unlimited swap lines between the C6—the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank of Canada—can be seen as a first step in the direction of creating such a global lender of last resort.

A lender of last resort is needed whenever everyone wants to sell risk exposure but no one wants to buy, even as the price of risky assets continues to fall. Central banks act as lenders of last resort purchasing these risky assets and putting so a lower bound to their quotation. The fact that central banks can help in this way by creating money reflects the fact that financial crisis are mainly a matter of liquidity (see Chap. 1, Sect. 1.2). However, when a solvency issue is at play, liquidity backstop is not sufficient and capital injection is required.

A final consideration is that credit intermediation is essentially the transformation of maturity and liquidity. Maturity mismatch is an inherent by-product of credit intermediation whereby short-term liabilities are transformed into long-term assets. Since the liability side of the bank balance sheet is typically shorter in duration than the asset side, banks tend to be adversely affected by rising interest rates.

During a prolonged period of very low short-term interest rates and a steep yield curve, institutions are tempted to make money by essentially borrowing short and lending long. However, structuring the bank portfolio in this way increases the institution’s vulnerability to losses in the event of rising interest rates. This is a threat which looms on the horizon after the extended period of low interest rates that followed the 2008 crisis.

Banks should be induced to match the maturities and reprising dates of their assets and liabilities, keeping away from assuming high levels of interest rate risk. There is a need to limit the size of asset–liabilities mismatch by means of an increase in longer-term liabilities. Banks should be induced to try to mobilize more long-term resources to expand their lending limit for long-term loans.

4 Europe: Current and Open Issues

4.1 The EMU’s Crisis-Hit Countries Assistance Programs

We now turn our attention to Europe. It is an opinion shared by many economists that the Eurozone is an “imperfect currency union” lacking effective mechanisms of fiscal transfer and sufficient levels of labor mobility at the interstate level (Pisani-Ferri et al. 2013; Sapir et al. 2014).

In this context, faced with the risk of a euro breakdown, policymakers adopted austerity measures whose impact in terms of economic growth is highly controversial and risks are pro-cyclical.Footnote 3

We discuss these problems in this section, beginning with the financial assistance granted to the Eurozone crisis-hit countries in exchange of an implementation of an economic adjustment program whose aim was to regain the international competitiveness of these countries.

In May 2010, Greece became the first euro area country to receive financial assistance from the EU and the IMF. The financial assistance was combined with a commitment to implement an economic adjustment program that was designed in discussions between the national authorities and the so-called Troika, consisting of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

On November 21, 2010, Ireland became the second euro area country to request financial assistance, followed by Portugal in April 2011. Roughly 2 years later, in March 2013, Cyprus also applied for financial assistance.

What makes all four programs special is the fact that they were undertaken within a monetary union. This had a number of important implications. First, the exchange rate was permanently fixed and no competitive devaluation was possible, in contrast to many IMF programs outside monetary union (Pisani-Ferri et al. 2013, 37). Although potential growth crucially relies on structural competitiveness factors, an initial exchange rate devaluation could have “jump started” the economy of program countries, alleviating the short-term consequences of fiscal retrenchment (Svensson 2001).

Second, the monetary union had led to a large increase in cross border financial integration and capital flows. The large lending flows via the banking system led to the buildup of larger cross border financial exposures and also permitted the financing of extraordinarily large external debt levels. Average external debt levels of close to 100 % of GDP at the beginning of the programs were more than twice as high as external debt levels in typical IMF program countries. The resulting financial contagion made debt restructuring more difficult.

Third, the common central bank, the ECB, provided large amounts of financing to the banking systems of member countries and thereby prevented that the balance of payment crisis turned into a full-blown funding crisis and a meltdown of the financial system, which eventually would have meant the introduction of a new currency in one or more crisis-hit countries.

Sapir et al. (2014) provide a systematic evaluation of financial assistance for Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Cyprus. All four programs, and in particular the Greek one, are very large financially compared to previous IMF’s programs, because macroeconomic imbalances and the loss of price competitiveness that were accumulated by crisis-hit countries appeared exceptional (see Chap. 5, Sect. 5.5).

Yet programs were based on far too optimistic assumptions about adjustment and recovery in Greece and Portugal. In all four countries, unemployment increased much more significantly than expected. Although fiscal targets were broadly respected, debt-to-GDP ratios ballooned in excess of expectations due to sharp GDP contraction.

The GDP deterioration was due to four factors: larger-than-expected fiscal multipliers; a poorer external environment, including an open discussion about euro area breakup; an underestimation of the initial challenge; and the weakness of administrative systems and of political ownership. The focus of surveillance of conditionality evolved from fiscal consolidation to growth-enhancing structural measures.

The Greek program is the least successful one. Ireland successfully ended the program in December 2013, but problems remain in the banking system. Exit from the Portuguese program in May 2014 was accompanied by a precautionary credit line. It is too early to make pronouncements on the Cypriot program, which only started in May 2013, but it can safely be said that there have been major collective failures of both national and EU institutions in the run-up of the program (Sapir et al. 2014).

The Troika programs stand out compared to typical IMF programs because of their exceptionally long durations and the exceptionally large size of the financial assistance packages. One reason for this is that the buildup of imbalances in all economies at the start of the program was much more significant than in typical IMF program countries. Another one is that, unlike many IMF programs, official assistance entirely substituted markets in the financing of sovereign borrowing needs.

Economic and social hardship remains severe in all countries. However, assessment cannot stop there and has to be based on a comparison between reasoned expectations and outcomes. Against this yardstick, the programs have so far been successful, though subject to risks, in two of the four countries under international financial assistance, Ireland and Portugal, which regained access to financial markets, not yet completely successful in Cyprus, and completely unsuccessful in Greece, which is on a totally different trajectory to the other Eurozone countries.

In the first two countries, Ireland and Portugal, we can say that the programs have been successful in some ways and unsuccessful in others. The main success has been in the current account, with deficits shrinking much faster than expected. Although depending on the country concerned, the reasons for this are either encouraging (an improvement in exports) or discouraging (a collapse of imports because of the recession).

Cyprus has outperformed Greece in implementing reforms and is now on track to exit its €10 bn bailout program ahead of schedule. Anyway, it still faces the threat of nonperforming loans, which are at €23 bn, well in excess of the island’s total output of €17 bn. These are seen as the bigger obstacle to financing the local economy. At close to half of banks’ total lending and still on the rise, the nonperforming loans are also viewed as the greatest challenge to the Cypriot banking system.

The high level of nonperforming loans remains the major not completely solved problem to address also for Ireland, which has a potential to be the fastest-growing Eurozone country in 2015 (3.9 % according to IMF’s spring forecast). The more forthcoming collectively borrowers and the lenders can be in addressing nonperforming loans, the faster the banking sector will restart and the more they can create room on their balance sheet to extend new loans to the economy. Ireland is a country that has been hit extremely hard by the crisis, but it made a lot of efforts and is now starting to reap the fruits of these efforts. It has reaped benefits not only in terms of growth but also in terms of restoring market access and lowering the cost of government funding (Cœuré 2015).

In Greece, early assumptions by the Troika about the ability of the economy to adjust and of the Greek political–administrative system to implement program measures proved unrealistic. By contrast, the Irish and Portuguese programs were based on more realistic assumptions, and implementation of program conditionality was much better.

The four countries under financial assistance have by and large adopted the austerity measures prescribed to them by the Troika. In structural terms they all implemented significant consolidation efforts. They had little choice since lender countries were unwilling to provide more financing. The alternative to austerity would have been debt restructuring.

In the Greek case, earlier restructuring would have been preferable, at least from a Greek point of view. In the Irish case, the bail-in of senior bank bondholders might have been desirable from the Irish point of view. But it would have improved the program’s sustainability far less than in Greece, and it could have had significant negative implications for the funding of Irish banks.

In the absence of expansionary measures elsewhere in the euro area, austerity measures in program countries, the loss of confidence in the euro, and the fragmentation of the euro financial system (see Chap. 6, Sects. 6.5 and 6.6) severely depressed growth. The recession was deeper or much deeper than anticipated. Together with the collapse of labor-intensive sectors such as construction, this also implied that unemployment increased far more than anticipated.

Compared to earlier IMF programs, the drop in GDP and the slow adjustment in the real exchange rate in all the four euro area countries under financial assistance were exceptional, but this is also true for Italy and Spain.

4.2 The Unsuccessful Results of the First Two Assistance Programs in Greece: Is There a Third Bailout Coming?

In Greece, this situation risks jeopardizing the sustainability of the countries’ necessary adjustment. Moreover, even if the Greek debt restructuring was the largest in history, Greece still remains an open problem. In fact, ever since the euro crisis erupted in late 2009, Greece has been at its heart. It was the first country to receive a bailout, in may 2010. It also was the subject of repeated debate over a possible departure from the single currency (the so-called Grexit) in 2011, again in 2012, and once more in 2015, after Syriza, the far-left Populist Party led by Alexis Tsipras, won the political elections in January.

At its root, the problem with Greece is simple but dramatic. Greece does not have enough money to pay its bills. Since the financial crisis began, its economy has shrunk by more than any other Eurozone economy. Between 2008 and 2014, nominal GDP fell by 22 %, much more than any other European country. House prices are down by around 40 % since 2008, and median income fell by 22 % between 2008 and 2014.

After a first bailout it received in 2010 (for a total of €110 bn), Greece received a second one in 2012 (€130 bn). This shifted most of its debts from old private to new public creditors, but, despite losses imposed on some private sector lenders, it did little to lower the whole debt. At the end of 2009, Greece owed €301 bn (127 % of GDP) mainly to private sector. In 2015 it owes €316 bn (175 % of GDP), most of which is now owned by European institutions (€187.5 bn), the ECB (€26 bn), and the IMF (€32.5 bn). Only €70 bn is owned by private sector.Footnote 4

In 2014, Greece seemed to be on the mend: after 6 years of recession, unemployment appeared to have peaked and the economy had started to grow. But in January 2015 something went wrong, after Syriza won the vote on the promise of a strong anti-austerity program. On the contrary, austerity programs were a condition of the bailouts and for receiving financial assistance from the EU, the ECB, and the IMF (the so-called Troika). Soon after he won the elections, Tsipras applied for a substantial restructuring of Greek public debt and also asked for a substantial debt haircut.

On February 11, 2015, the Eurogroup of financial ministers of the 19 Eurozone countries met in Brussels to find a way out of the latest phase of the Greek crisis. They agreed, in disarray with Tsipras’s request, that Greece should have respected the existing assistance procedures and should have applied the Troika of EU-ECB-IMF for an extension of the old assistance program, which was going to expire on February 28.

Even countries like France and Italy, who might otherwise be sympathetic to Mr. Tsipras’s anti-austerity message, ruled out debt haircuts, not least because they would lose out themselves. Further, the ECB autonomously decided to cut off its main extraordinary line of support to Greek banks, which meant that Greece in a few days should not have had the money to pay public servants.

Greece’s new public creditors (EU, ECB, and IMF) are both generous and demanding. They decided that the country’s interest rate paid to them should have been slashed: its total interest rates payments in 2014 were just 2.6 % of GDP, lower than several less indebted European countries.

But the money comes with conditions aimed at stabilizing Greece’s finances. These include cuts to Greece’s minimum wage and pensions, layoffs of civil servants, and the privatization of various assets, including ports and state-owned buildings. Creditors like Germany hope the package will make Greece more competitive and thus spur economic growth, as well as generating a budget surplus to be used to pay down debt.

Before the old assistance program expired on February 28, Greece agreed to talk to its creditors to find a way out of its international bailout and applied to the Eurogroup for a temporal extension of the old program to agree a new solution to the crisis.

The Eurogroup reiterated its appreciation for the remarkable adjustments efforts undertaken by Greece over the last years and agreed an extension of 4 months of the old program to gain time and prepare for a possible new third bailout of between €30 and 50 bn.

The resolution was approved in exchange of a strong commitment of Greek authorities “to a broader and deeper structural reform process, aimed at durably improving growth and employment prospects, ensuring stability and resilience of the financial sector and enhancing social fairness.”

The authorities also committed “to implementing long overdue reforms to tackle corruption and tax evasion, and improving efficiency of the public sector”. The Greek authorities should have reiterate “their unequivocal commitment to honour their financial obligations to all their creditors fully and timely”. Further, the Greek authorities should “have also committed to ensure the appropriate primary fiscal surpluses or financing proceeds required to guarantee debt sustainability in line with the November 2012 Eurogroup statement”.Footnote 5

Finally, the Greek authorities also committed to refrain from any rollback of measures and unilateral changes to the policies and structural reforms that would negatively impact fiscal targets, economic recovery, or financial stability, as assessed by the institutions.

With respect to the electoral promises, it is obvious that Mr. Tsipras could hardly hide from his own radical supporters the fact that he had made a series of painful climb-downs.

First, he had abandoned his Syriza party’s preelection pledge to write off a big chunk of Greece’s sovereign debt and hence draw a line under 5 years of harsh austerity imposed by the hated “Troika”. But he had no choice, because he needed new money to escape default.

Add that Athens bankers were already worried by a steady outflow of deposits: close to €20 bn had been withdrawn in the first 2 months of 2015. If a deal had fallen through, capital controls would have been imposed, bringing a renewed threat of “Grexit” from the euro.Footnote 6

That prospect has receded for the moment, but Greece is still on a knife-edge. Despite the insistence that Syriza’s electoral program was still on track, the list of tax, revenue, and structural measures he proposed to “the institutions”, as the Troika was renamed to soothe voters, looked familiar with those accepted by the previous center-right government.

There are plenty of obstacles along the way, as Syriza also promised its creditors not to roll back reforms already in place. But sticking to that would mean abandoning plans which are cherished by its voters, such as relaunching collective wage bargaining and raising the minimum monthly wage to €750, the precrisis level.

4.3 Some Remaining Institutional Matters

Turning to institutional matters, EU–IMF cooperation clearly played an important role in the design, monitoring, and, ultimately, the implementation of the crisis-hit countries programs.

Though fraught with many potential problems, EU–IMF cooperation to deal with the crisis was inevitable in euro area countries. From the EU side, despite various political misgivings, recourse to the IMF was necessary because the EU lacked expertise on, and experience of, crisis funding and also lacked sufficient trust in its own institutions to act alone.

Despite a number of tensions stemming from their different logic and rules, the EU and the IMF succeeded in cooperating in Ireland and Portugal, much less in Greece. The issue on which Troika members disagreed most was the risk of financial spillovers between euro area countries, which led to divergent views about the Greek debt restructuring and about imposing losses on senior bondholders of Irish banks, two options that the IMF viewed favorably.

Pisani-Ferri et al. (2013) evaluation of the functioning of the Troika reveals a number of problems for each of its members, which give rise to a number of reform proposals.

First, they argue that the European Commission’s dual role, as an agent of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the Eurogroup, from one side, and as a European Union institution, from the other, is problematic and can lead to conflicts of interest. Therefore, they propose that, eventually, the role should shift to a European Monetary Fund (EMF), which would replace the ESM and would be a true EU institution. A narrowly mandated agency would also be less exposed to different policy objectives.

Second, the ECB is involved in the Troika in liaison with the European Commission. It does not offer program assistance per se but provides crucial liquidity assistance to banks in program countries. Therefore, ECB participation in the Troika is necessary for it to have access to full information and to retain the ability to voice concerns.

Yet, its role should not be one of a full negotiating partner because of potential conflicts of interest. Currently, the ECB does not publish independent documents on the programs but it does cosign mission statements. Pisani-Ferri et al. (2013) recommend that it discontinues cosigning such statements and behaves as a “mostly silent” participant in the Troika.

Third, the IMF has become much more involved in the euro area operationally and financially than deemed sustainable by its shareholders. Pisani-Ferri et al. (2013) envisage possible evolutions of its role and conclude that it should become a “catalytic lender” whose participation in programs would be desirable, as long as the euro area has not set up an EMF and become a member of the IMF but that could abstain from taking part without putting the whole package in jeopardy.

In concrete terms, this would imply limiting IMF participation to about 10 % of total financing. More generally, Pisani-Ferri et al. (2013) regard EU–IMF cooperation as an important template for future cooperation between global and regional financial institutions. In this respect, the euro area crisis is an important test of the feasibility of such cooperation.

4.4 Has the ECB the Role of Lender of Last Resort?

In the European monetary union (EMU), all these major events characterized the evolution of the crisis, not only for those economies that entered in a financial assistance program but also for all the other member states. In fact, the Eurozone sovereign debt and banking crises have exposed the structural weaknesses of the Eurozone. These structural weaknesses are intrinsic to a monetary union and depend on the fact that the EMU countries issue debt in a currency, the euro, over which they have no control.

As a result, when a recession hits and public finances deteriorate, market panic can be set in motion, leading to large surges in the government bond spreads and a sudden stop in liquidity provision, forcing governments of Eurozone countries into quick and intense austerity (see Chap. 1, Sect. 1.3, and Chap. 8, Sect. 8.6). In stand-alone countries, these surges in spreads and sudden stops are avoided because of the existence of national central banks that will provide liquidity in times of crisis (De Grauwe and Ji 2015; De Grauwe 2011).

In this regard, an important side issue of the debate on the tasks usually attributed to central banks is the discussion if the ECB can behave as a lender of last resort. According to De Grauwe and Ji (2015), as illustrated in Chap. 5, Sect. 5.4, the structural weakness of the Eurozone countries arises from the absence of a backstop, that is, a lender of last resort, in the government bond markets, making sovereign debts in the Eurozone vulnerable to market sentiments of fear and panic.

When these sentiments surge, they can lead to self-fulfilling liquidity crises characterized by sharp increases in the government bond rates, sudden stops in liquidity in the government bond markets, and intense austerity measures. As these crises typically erupt when the economy experiences a downturn, these austerity measures have the effect of switching off the automatic stabilizers in the government budget. As a result, the economic recessions are made more intense and can lead to social and political instability in the countries concerned (De Grauwe and Ji 2015).

Against this dangerous evolution of the crisis, Eurozone countries have successfully taken political as well as technical measures. From a political point of view, as we pointed out in Chap. 6, Sect. 6.5, since 2012 the European Council of the heads of states and governments of the EU approved the creation of a banking union and a unified banking supervision housed within the ECB. They also approved to create a common deposit insurance for households and a common bank resolution rule. Finally, they decided to move toward a fiscal union and more political integration and that troubled countries and their banking systems could directly access to Eurozone rescue funds (EFSF, EFSM, and ESM).

Over the following months, many steps forward have been taken toward an effective governance of the Eurozone in order to guarantee financial stability, through the signature of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination, and Governance (also known as the Fiscal Compact), the Six Pack, and the Two Pack Agreements.

To complement this policy, not less important for overcoming the crisis and stabilizing the European financial markets were the technical measures decided by the ECB. These include first, the approval, between December 2011 and February 2012, of two unconventional long-term refinancing operations (LTRO) for a total of more than €1.000 bn at a fixed rate of 1 %, maturing 3 years later; second, president Mario Draghi’s announcement in July 2012 that the ECB would have done “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro and to struggle the crisis; third, the ECB’s approval, on September 6, 2012, of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program, under which the Bank decided to engage in buying in secondary markets unlimited sovereign bonds of troubled countries, with a maturity of between 1 and 3 years; and fourth, the ECB’s announcement, on January 22, 2015, to proceed with nonconventional monetary policies yet decided some months before and, among them, to engage in a full quantitative easing monetary policy.Footnote 7

4.5 The ECB’s Quantitative Easing Monetary Policy

A quantitative easing (Qe) monetary policy was due to combat the increasing risks of deflation in the euro area. In fact, the headline rate of inflation stayed below 1 % throughout 2014, reaching the negative sign of −0.2 % in December and −0.6 % in January 2015, while the bank’s goal rate is of almost 2 %. A prolonged spell of “low inflation” which tends to become deflation is bad for the area because many of its member states are weighed down by excessive public and private debt. If outright deflation were to take grip, it would arm borrowers, because when prices fall, the real burden of debt increases.

Furthermore, the ECB could no longer help by cutting interest rates. It lowered its main lending rate in September 2014 to just 0.05 %, while charging banks on deposits they leave with it, through a negative rate of 0.2 %. The ECB had hoped to reverse the shrinking of its balance sheet, after commercial banks reimbursed their 2011–2012 LTROs, through another more extended round of long-term funding operations, providing liquidity until 2018 at a fixed rate of just 0.15 % a year. But the first two of eight ECB’s planned lenders have been a disappointment: in September and December 2014, banks borrowed only €212 bn, little more than half the €400 bn available.Footnote 8

So, the only way for the ECB to expand the size of its own balance sheet, which it intended returning at least to the high of €3.000 bn that it reached in early 2012, after the successful two extraordinary LTROs of December 2011 and February 2012 just mentioned above, was to proceed without further delay with Qe. The aim of the Bank is to reach the size of its own balance sheet of €3.000 bn in 2016 and €3.700 bn in 2017.

To reach these aims, the ECB has engaged in an expanded asset purchase program announced on January 22, 2015, which consists of combined monthly purchases of €60 bn each month in public and private sector securities, beginning March 9, 2015, and lasting at least until September 2016. These purchases are intended under the public sector purchase program (PSPP) of marketable debt instruments issued by euro area central governments, certain agencies located in the euro area, or certain international or supranational institutions.

Therefore, the ECB is now engaged in a full Qe monetary policy, which adds the purchase of sovereign bonds to its existing private sector asset purchase programs, in order to address the risks of a too prolonged period of low inflation.Footnote 9

All these decisions are aimed at fulfilling the ECB’s price stability mandate, which consists in achieving inflation rates below, but close to, 2 % over the medium term. The EBC is buying bonds issued by euro area central governments, agencies, and European institutions in the secondary market against central bank money, which the institutions that sold the securities can use to buy other assets and extend credit to the real economy. In both cases this contributes to an easing of financial conditions.Footnote 10

There are two main channels through which Qe is likely to work in the euro zone. One is the “signaling” effect that the ECB is sending a clear message to markets and to firms that it is determined to bring inflation closer to 2 %. The other is through the exchange rate. The euro has already been weakening since spring 2014, and it is expected to reach the parity with the dollar, after it reached the exchange rate of 1.08 on March 2015. A sharp drop in the euro is considered very important for recovery in the Eurozone.

In regard to the risk sharing, which implies the sharing of hypothetical losses in the extreme event of a full uncooperative euro breakup (see Chap. 6, Sect. 6.3), the ECB decided that purchases of securities of European institutions (EFSF, EFSM, and ESM), which will be 12 % of the additional asset purchases and which will be purchased by national central banks (NCBs), will be subject to loss sharing.

The rest of the NCBs’ additional asset purchases will not be subject to loss sharing. As the ECB will hold 8 % of the total asset purchases, this implies that not more than 20 % of the additional asset purchases will be subject to a regime of risk sharing.

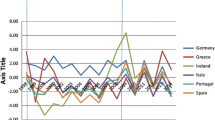

Until the first months of 2015, the whole ECB’s monetary policy decisions have had two main effects: first, the harmonized long-term interest rates calculated by the ECB for convergence assessment purposes,Footnote 11 and based on the secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of close to 10 years, have shrunk in all countries, except for Greece;Footnote 12 second, as mentioned above, they have had a significant effect on the exchange rate of the euro.

By increasing the supply of money base with a Qe policy, the ECB will certainly contribute to a further weakening of the euro vis-à-vis other currencies such as the dollar, the pound, and the yuan, thereby increasing exports and boosting inflation.

Can these decisions of the ECB be interpreted as corresponding to the behavior of a lender of last resort for public debts of Eurozone countries? The answer is no, because unlike other central banks (Fed, BoE, and BoJ), the ECB lacks a state: it is forbidden by the EMU’s rules to buy public bonds in primary markets and to finance directly public deficits of member states (the no-bailout clause of Article 125 of the EU Treaty).

Anyway, the effects of these decisions on the stabilization and harmonization of European financial markets are very important, because of, at the least, a partial risk sharing among Eurozone countries.

There is much misunderstanding and fear regarding Qe, especially in Germany and some other northern countries. The credit ratings of the EMU countries vary from AAA in Germany to junk in Greece. If the ECB buys government bonds from countries like Greece, German taxpayers risk having to pay the bill if Greek politics sour further.

If Greece defaults, it will create a loss on the balance sheet of the ECB. The other member countries of the Eurozone, especially Germany, will then have to cover the loss. The fear that German taxpayers may be forced to cover future losses of the ECB has become the main reason why the ECB has waited so long to begin with Qe.

In fact, this fear is funded only for the 20 % of the additional asset purchases that will be subject to a regime of risk sharing, while for the remaining 80 % of purchases that will not, each of the NCBs is responsible for the purchases of their national government bonds. These are permitted to each NCB in proportion to the economic weight that each country has in the Eurozone (ECB 2015a, b).

Thus, German NCB buys 27 % (of total Qe) of German bonds, French NCB buys 20 % of French bonds, Italy NCB buys 18 % of Italian bonds, and so on. As long as these bonds are kept on the ECB’s balance sheet, the governments of these countries pay interest to the ECB, which will then apply the rule of “juste retour”, that is, it reimburses the same amounts to each of these governments. So, no fiscal transfers between member states occur. If one government were to default on its bonds, it would stop paying interest, but at the same time, applying the “juste retour” clause, it would not get any interest refund. Again there would be no fiscal transfer among Eurozone member states (De Grauwe 2015b).

In conclusion, the ECB’s monetary policy for the time being remains a milestone of the well functioning of the EMU, even if it does not have a full role of lender of last resort. The recovery, since the double-dip recession between 2011 and 2014, has been weak and faltering, while deflation has tumbled.

The ECB has sought to combat deflation through a variety of means, including LTROs and negative interest rates on the deposit facility, to force banks to expand their credit to SMEs. But what it had yet not done was a massive Qe policy, similar to other central banks of most developed countries, which will boost its balance sheet, injecting money into the economy and stimulating activity.

The ECB’s final goal is to boost recovery in all Eurozone countries, which remains the main device to regain a smooth and efficient functioning of the EMU.

4.6 The Legacy of the Euro Crisis and Conclusions

In a closed-door seminar held in Milan on March 13, 2015, De Grauwe (2015a) summarizes as follows the present state of the EMU: the Eurozone, which was built on the promise of progressive integration and harmonization of countries sharing the same currency, has instead gradually split into creditor and debtor nations. Debtor countries were left with internal devaluation, and this meant higher unemployment and wage shrinking. This, in turn, generated stagnation in the Eurozone as a whole.

Further, austerity meant that the rebalancing imposed on euro area countries was asymmetric: debtor nations had to adopt fiscal tightening, while creditor countries could continue in their “business as usual” model. This asymmetric adjustment mechanism supported a deflationary bias in the Eurozone. This is because, by expecting low economic growth, economic operators also expected low inflation and low interest rates. Moreover, austerity forced debtor countries to increase their savings, and the low level of consumption again pushed inflation downwards.

According to De Grauwe, the most striking feature of the legacy of the euro crisis is that, despite intense austerity programs that have been triggered since 2010, there is no evidence that such programs managed to increase the capacity of debtor countries to continue to service their own debt. On the contrary, deflation or persistently low inflation makes it harder to reduce debt burdens, because the nominal debt level remains very near the real debt level or even increases. At the same time, austerity-induced stagnation in economic growth cannot act through the denominator of the debt/GDP level.

As we have strongly emphasized in the final section of Chap. 6 for Germany, De Grauwe’s contention is that a more symmetric fiscal adjustment, in which creditor nations properly stimulate their economies, would have reduced the price periphery countries have to pay to achieve a given improvement in their government budget balances. Therefore, first we need to solve the legacy of the euro crisis, and secondly we need to correct for design failures of the Eurozone.

In the first respect, the legacy of the crisis in the euro area has led to unsustainable debt levels in some debtor countries. According to De Grauwe, debt default and restructuring will be inevitable: the only question, then, is when to do it. A rational solution dictates that creditor nations accept a loss as soon as possible, in order to recover as much credit as possible from a defaulting debtor. The later they agree to do this, the less money they will recover from near-default countries such as Greece.

In fact, with respect to the evidence problem mentioned above, as we pointed out in Sect. 11.4.1 above, the financial assistance programs in crisis-hit countries have so far been successful, though subject to risks, in two of the four countries under international financial assistance, Ireland and Portugal, which regained access to financial markets; it was not yet completely successful in Cyprus, which anyway outperformed Greece in implementing reforms and is now on the track to exit its bailout program ahead of schedule; and it was completely unsuccessful only in Greece, which is on a totally different trajectory to the other Eurozone countries.

As far as the public debt service is concerned and De Grauwe’s contention that a restructuring will be inevitable, we think that this is not the right solution, because after a first debt restructuring governments will be induced to over-borrow again and again. In fact, as it will be pointed out in Chap. 12, at the end of Sect. 12.1, the reason why governments tend to over-borrow, with limits set only by the probability of defaulting, is relatively straightforward. Governments’ objective function is to maximize votes in the short run (next elections). Votes are positively correlated with public expenditure, because it always benefits some constituency and negatively correlated with taxes.

Therefore, debt is the straightforward way of transferring payments to future generations, and governments have too much incentive to maximize debt, only subject to the restrictions that the market imposes on them.Footnote 13

In light of all this, how can we redesign the Eurozone? In this regard, we agree with De Grauwe’s conclusion that there is no other alternative than to strongly increase coordination of macroeconomic policy among EMU countries. Ultimately, such coordination should bring about the completion of the banking union and the start of a real fiscal union. This in turn requires a real political union, following the principle of “no taxation without representation.”

In the short run, what we need is monetary and fiscal expansion at the EU level. The ECB has started its quantitative easing program, and that is for the better. However, we still need fiscal policy to be managed, or at least coordinated, at the EU level.

To conclude with De Grauwe’s words, the resilience of the Eurozone in the long run depends on the continuing process of political unification, which must proceed hand in hand with the creation of a fiscal union (Spolaore 2013). Such a political unification is needed because the Eurozone has dramatically weakened the power and legitimacy of member states’ governments and left a vacuum in their place instead of creating a supranational government. This would imply the creation of a supranational fiscal risk-sharing mechanism that could insure European countries against very severe downturns like the last Great Crisis (Furceri and Zdzienicka 2013).Footnote 14

Notes

- 1.

Edwards (2015) uses data on 180 sovereign defaults to analyze what determines the recovery rate after a debt restructuring process. Why do creditors recover, in some cases, more than 90 %, while in other cases they recover less than 10 %? He finds support for the Grossman and Van Huyk (1985) model of “excusable defaults”: countries that experience more severe negative shocks tend to have higher “haircuts” than countries that face less severe shocks. Edwards discusses in detail debt restructuring episodes in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Greece. The results suggest that the haircut imposed by Argentina in its 2005 restructuring was “excessively high.” The other episodes’ haircuts were consistent with Grossman and Van Huyk’s model.

- 2.

The Dodd–Frank Act implements changes that, among other things, affect the oversight and supervision of financial institutions, provide for a new resolution procedure for large financial companies, create a new agency responsible for implementing and enforcing compliance with consumer financial laws, introduce more stringent regulatory capital requirements, effect significant changes in the regulation of over-the-counter derivatives, reform the regulation of credit rating agencies, implement changes to corporate governance and executive compensation practices, incorporate the Volcker Rule, require registration of advisers to certain private funds, and effect significant changes in the securitization market. Further comments on the Dodd–Frank Act from an economic point of view are exposed by Acharya et al. (2010).

- 3.

To end the euro crisis and return the Eurozone countries to healthy growth rates of income and employment, Feldstein (2015) proposes to adopt revenue neutral fiscal incentives by the individual Eurozone countries, while Alesina et al. (2015) show that fiscal adjustments based upon cuts in spending appear to have been much less costly, in terms of output losses, than those based upon tax increases, and the difference between the two types of adjustment is very large.

- 4.

Forni and Pisani (2013) assess the macroeconomic effects of a sovereign restructuring in a small economy belonging to a monetary union by simulating a dynamic general equilibrium model. In line with the empirical evidence, they make the following three key assumptions: first, sovereign debt is held by domestic agents and by agents in the rest of the monetary union; second, after the restructuring the sovereign borrowing rate increases and its increase is fully transmitted to the borrowing rate paid by the domestic agents; and third, the government cannot discriminate between domestic and foreign agents when restructuring. They show that the macroeconomic effects of the restructuring depend on (a) the share of sovereign bonds held by residents in the country as compared to that held by foreign residents, (b) the increase in the spread paid by domestic agents, and (c) its net foreign asset position at the moment of the restructuring. Their results also suggest that the sovereign restructuring implies persistent reductions of output, consumption, and investment, which can be large, in particular if the share of public debt held domestically is large, the private foreign debt is high, and the spread paid by the government and the households does increase.

- 5.

“Eurogroup statement on Greece,” approved on 20 February 2015.

- 6.

“Greece and the euro: Doing the splits,” The Economist, February 28, 2015.

- 7.

Friedman (2014) argues that one of the two forms of hitherto unconventional monetary policy that many central banks have implemented in response to the 2007 financial crisis—large-scale asset purchases or, to put the matter more generically, the use of the central bank’s balance sheet as a distinct tool of monetary policy—is likely to become part of the standard toolkit of monetary policymaking in normal times as well. As intended, these purchases have lowered long-term interest rates relative to short-term rates and lowered interest rates on more-risky compared to less-risky obligations. Moreover, their introduction fills a conceptual vacuum that has long stood at the heart of monetary policy analysis and implementation. In contrast to the last century or more of monetary theory, which has focused on central banks’ liabilities, the basis for the effectiveness of central bank asset purchases turns on the role of the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet. The implications for monetary theory are profound.

- 8.

Anyway, Neri and Ropele (2015) share the opinion that the accommodative monetary policy stance of the ECB helped to moderate the negative effects of the sovereign debt tensions.

- 9.

The ECB’s Qe program, which will encompass the asset-backed securities purchase program and the covered bond purchase program, both launched in 2014, as just mentioned in the text, will amount to €60 bn monthly. Starting on March 2015, it will be carried out until at least September 2016, for a total of bond purchases of €1140 bn. This figure compensates the ECB’s withdrawal of about €1.000 bn out of the Eurozone economy as the result of banks repaying loans they had taken during the last 2 years of the debt crisis.

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

Some examples are illustrative: Italian bonds long-term interest rates (10-year government bond yields) decreased from 3.87 % in January 2014 to 1.70 % in January 2015, Ireland bonds from 3.39 % to 1.22 %, Spain bonds from 3.79 % to 1.54 %, Portugal bonds from 5.21 % to 2.49 %, France bonds from 2.38 % to 0.67 %, and Germany bonds from 1.76 % to 0.39 %. Only Greece bond yields augmented their 10-year rate of return from 8.18 % to 9.48 % in the same period. Anyway, Turner (2013) advises that an extended period of very low long-term interest rates and high public debt creates financial stability risks. Interest rate risk in the banking system has grown, and some institutional investors face significant exposures. Central banks in the advanced economies now hold a high proportion of bonds issued by their governments, most of which have so far failed to arrest the rise in the ratio of government debt to GDP. Implementing an effective exit strategy will be difficult. According to Turner, current policy frameworks should be reconsidered, with a view to clarifying the importance of the long-term interest rate for monetary policy, for financial stability, and for government debt management.

- 13.

Fochmann et al. (2014) use a controlled laboratory experiment with and without overlapping generations to study the emergence of public debt. Public debt is chosen by popular vote, pays for public goods, and is repaid with general taxes. With a single generation, public debt is accumulated prudently, never leading to over-indebtedness. With multiple generations, public debt is accumulated rapidly as soon as the burden of debt and the risk of over-indebtedness can be shifted to future generations. Debt ceiling mechanisms do not mitigate the debt problem. With overlapping generations, political debt cycles emerge, oscillating with the age of the majority of voters.

- 14.

According to Guiso et al. (2015), entering a currency union without any political union, European countries have taken a gamble: will the needs of the currency union force a political integration (as anticipated by Jean Monnet) or will the tensions create a backlash, as suggested by Nicholas Kaldor, Milton Friedman, and many others? They try to answer this question by analyzing the cross-sectional and time series variation in pro-European sentiments in the EU 15 countries. They conclude that 1992 Maastricht Treaty seems to have reduced the pro-Europe sentiment as does the 2010 Eurozone crisis. Yet, in spite of the worst recession in recent history, the Europeans still support the common currency. Europe seems trapped: there is no desire to go backward and no interest in going forward, but it is economically unsustainable to stay still.

References

Acharya V, Cooley TF, Richardson M, Sylla R, Walter I (2010) A critical assessment of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform and consumer protection act. Vox CEPR’ policy portal, Nov 24. Available via http://www.voxeu.org/article/dodd-frank-critical-assessment

Alesina AF, Barbiero O, Favero CA, Giavazzi F, Paradisi M (2015) Austerity in 2009–2013. NBER working paper no. 20827, January. Available via http://www.nber.org/papers/w20827

Bair S (2011) Examining and evaluating the role of the regulator during the financial crisis an today, Statement before the house subcommittee on financial institutions and consumer credit. Mimeo Available via https://www.fdic.gov/news/news/speeches/archives/2011/spmay2611.html

Bird M (2015) The ECB just gave a major boost to Europe’s growth forecast. Business Insider UK, Mar 5. Available via http://uk.businessinsider.com/european-central-bank-ecb-press-conference-march-2015-2015-3?r=US

Bird M, Pozzebon S (2015) Europe’s massive quantitative easing scheme just arrived – Here’s everything you need to know. Business Insider UK, Jan 22. Available via http://uk.businessinsider.com/ecb-meeting-january-2015-2015-1#ixzz3TW4eChfk

Cœuré B (2015) Interview with the Irish times, Jan 16. Available via http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/inter/date/2015/html/sp150116.en.html

De Grauwe P (2011) The European central bank: lender of last resort in the government bond markets? CESifo working paper no. 3569. Available via https://www.google.it/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=7.+De+Grauwe+P.+(2011)%2C+%E2%80%9CThe+European+Central+Bank%3A+Lender+of+Last+Resort+in+the+Government+Bond+Markets%3F%E2%80%9D%2C+CESifo+Working+Paper+No.+3569

De Grauwe P (2015a) Eurozone in the Doldrums. The legacy of the eurocrisis. Closed-door workshop, ISPI-Milan, Mar 13. Available via http://www.ispionline.it/DOC/lecture_de_grauwe.pdf

De Grauwe P (2015b) The sad consequences of the fear of Qe. The Economist, Jan 21

De Grauwe P, Ji Y (2015) Has the eurozone become less fragile? Some empirical tests. CESifo working paper series no. 5163, Jan 26

Dudley WC (2014) Enhancing financial stability by improving culture in the financial services industry. Remarks at the workshop on reforming culture and behavior in the financial services industry, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, New York City. Available via http://www.ny.frb.org/newsevents/speeches/2014/dud141020a.html

ECB (2015a) Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A), Jan 22. Available via http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2014/html/is140109.en.html

ECB (2015b) Press release: ECB announces expanded asset purchase programme, Jan 22. Available via http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2015/html/pr150122_1.en.html

Edwards S (2015) Sovereign default, debt restructuring, and recovery rates: was the Argentinean ‘Haircut’ Excessive? NBER working paper no. W20964, February. Available via http://www.nber.org/papers/w20964

Feldstein MS (2015) Ending the euro crisis. NBER working paper no. W20862, Available via http://www.nber.org/feldstein/w20862.pdf

Fochmann M, Sadrieh A, Weimann J (2014) Understanding the emergence of public debt. CESifo working paper series no. 4820, May. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2436292

Forni L, Pisani M (2013) Macroeconomic effects of sovereign restructuring in a monetary union: a model-based approach. IMF working paper no. 13/269, December. Available via https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=41176.0

Friedman BM (2014) Has the financial crisis permanently changed the practice of monetary policy? Has it changed the theory of monetary policy? NBER working paper no. W20128, May. Available via http://www.nber.org/papers/w20128

Furceri D, Zdzienicka A (2013) The euro area crisis: need for a supranational fiscal risk sharing mechanism? IMF working paper no. 13/198, September. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2342177

Grossman HI, Van Huyk JB (1985) Sovereign debt as a contingent claim: excusable default, repudiation, and reputation. NBER working paper no. 1673 (Also reprint no. r1244), July. Available via http://www.nber.org/papers/w1673

Group of Thirty (2009) Financial reform: a framework for financial stability. Available via http://www.group30.org/images/PDF/Financial_ReformA_Framework_for_Financial_Stability.pdf

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2015) Monnet’s Error? NBER working paper no. w21121, April. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2599387

Lynch R (2015) Quantitative easing imminent as ECB Boss Mario Draghi fires €1.1trn starting gun. The Independent, Mar 6

Mehrling P (2014) Why central banking should be re-imagined. BIS papers N° 79. Available via http://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap79i.pdf

Neri S, Ropele T (2015) The macroeconomic effects of the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area. Bank of Italy working paper no. 1007, Mar 27. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2600900

Pisani-Ferri J, Sapir A, Wolff GB (2013) EU-IMF assistance to euro-area countries: an early assessment. Bruegel blueprint series, XIX

Sapir A, Wolf GB, De Susa C, Terzi A (2014) The Troika and financial assistance in the euro area: successes and failures. Studies on the request of the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee, Directorate General for Internal Policies of the European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit (ed), February. Available via https://www.google.it/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=4.+Sapir+A.,+G.+B.+Wolf,+C.+De+Sousa+and+A.+Terzi+(2014),+The+Troika+and+Financial+Assistance+in+the+Euro+Area:+Successes+and+Failures,+Studies+on+the+request+of+the+Economic+and+Monetary+Affairs+Committee,+Directorate+General+for+Internal+Policies+of+the+European+Parliament,+Economic+Governance+Support+Unit+(Ed.),+February&spell=1

Spolaore E (2013) What is European integration really about? A political guide for economists. CESifo working paper series no. 4283, June. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2284804

Svensson LEO (2001) The zero bound in an open economy: a foolproof way of escaping from a liquidity trap. Monetary and economic studies (Special Edition), February. Available via http://www.hkimr.org/uploads/seminars/409/sem_paper_0_94_svensson-paper171202.pdf

Turner P (2013) Benign neglect of the long-term interest rate. BIS working paper no. 403, February. Available via http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2247907

WP (2015) The European central bank: let the show begin. The Economist, Mar 5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Beker, V.A., Moro, B. (2016). Current Issues and Policies. In: Modern Financial Crises. Financial and Monetary Policy Studies, vol 42. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20991-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20991-3_11

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20990-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20991-3

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)