Abstract

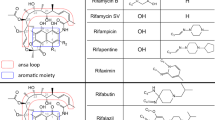

Rifampin is a macrocyclic antimicrobial agent synthetically derived from many generations of rifamycin B, a virtually inactive metabolite of Streptomyces mediterranei. In 1968, an active product was conceived, rifamycin SV, which showed activity against gram-positive organisms [1]. Rifampin, a hydrazone derivative of 3-formylrifamycin SV, is used today in various settings as a broad-spectrum agent against gram-positive organisms (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae) and gram-negative organisms (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas) [2]. More commonly, rifampin is used as a synergistic, bactericidal agent against tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sensi P. History of the development of rifampin. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5 Suppl 3:S402–6.

Loeffler AM. Uses of rifampin for infections other than tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:631–2.

Campbell EA, Korzheva N, Mustaev A, et al. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell. 2001;104:901–12.

Holdiness MR. A review of the redman syndrome and rifampicin overdosage. Med Toxicol Adverse drug Exp. 1989;4:444–51.

Hong Kong Chest Service/Tuberculosis Research Centre, Madras/ British Medical Research Council. A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of three antituberculosis chemoprophylaxis regimens in patients with silicosis in Hong Kong. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:36–41.

Dossing M, Wilcke JT, Askgaard DS, et al. Liver injury during antituberculosis treatment: an 11-year study. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996;77:335–40.

Lange P, Oun H, Fuller S, et al. Eosinophilic colitis due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1994;344:1296–7.

Dutt AK, Moers D, Stead WW. Undesirable side effects of isoniazid and rifampin in largely twice-weekly short-course chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:419–24.

Covic A, Golea O, Segall L, et al. A clinical description of rifampicin-induced acute renal failure in 170 consecutive cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:924–9.

De Vriese AS, Robbrecht DL, Vanholder RC, et al. Rifampicin-associated acute renal failure: pathophysiologic, immunologic, and clinical features. J Indian Med Assoc. 2004;102(1):20. 22-5.

Patel GK, Anstey AV. Rifampicin-induced lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:260–2.

Burman WJ, Gallicano K, Peloquin C. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the rifamycin antibacterials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:327–41.

McKeon J, Patel AM. Antituberculous therapy and acute liver failure. Lancet. 1995;345:1170–1.

Di Piazza S, Cottone M, Craxi A, et al. Severe rifampicin-associated liver failure in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Lancet. 1978;1:774.

ANON. Position statement and practice guidelines on the use of multi-dose activated charcoal in the treatment of acute poisoning. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1999;37:731–751.

Blanchet KD. Current management practices in the treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1996;10:116–21.

Williams DL, Pittman TL, Gillis TP, et al. Simultaneous detection of Mycobacterium leprae and its susceptibility to dapsone using DNA heteroduplex analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2083–8.

Triglia T, Menting JG, Wilson C, et al. Mutations in dihydropteroate synthase are responsible for sulfone and sulfonamide resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13944–9.

Booth SA, Moody CE, Dahl MV, et al. Dapsone suppresses integrin-mediated neutrophil adherence function. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:135–40.

Zhu YI, Stiller MJ. Dapsone and sulfones in dermatology: overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;45(3 Pt 1):420–34.

Rees R, Campbell D, Rieger E, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of brown recluse spider bites. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:945–9.

Jollow DJ, Bradshaw TP, McMillan DC. Dapsone-induced hemolytic anemia. Drug Metab Rev. 1995;27:107–24.

Solheim L, Brun AC, Greibrokk TS, et al. Methemoglobinemia – causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2000;120:1549–51.

Lambert M, Sonnet J, Mahieu P, et al. Delayed sulfhemoglobinemia after acute dapsone intoxication. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1982;19:45–60.

Kenner DJ, Holt K, Agnello R, et al. Permanent retinal damage following massive dapsone overdosage. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64:741–4.

Chugh KS, Singhal PC, Sharma BK, et al. Acute renal failure due to intravascular hemolysis in the North Indian patients. Am J Med Sci. 1977;274:139–46.

Woodhouse KW, Henderson DB, Charlton B, et al. Acute dapsone poisoning: clinical features and pharmacokinetic studies. Hum Toxicol. 1983;2:507–10.

Elonen E, Neuvonen PJ, Halmekoski J, et al. Acute dapsone intoxication: a case with prolonged symptoms. Clin Toxicol. 1979;14:79–85.

Kugler W, Pekrun A, Laspe P, et al. Molecular basis of recessive congenital methemoglobinemia, types I and II: exon skipping and three novel missense mutations in the NADH-cytochrome b 5 reductase (diaphorase 1) gene. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:348.

Coleman MD. Dapsone-mediated agranulocytosis: risks, possible mechanisms and prevention. Toxicology. 2001;162:53–60.

Chalasani P, Baffoe-Bonnie H, Jurado RL. Dapsone therapy causing sulfone syndrome and lethal hepatic failure in an HIV-infected patient. South Med J. 1994;87:1145–6.

Coleman MD, Coleman NA. Drug-induced methaemoglobinaemia: treatment issues. Drug Saf. 1996;14:394–405.

Mansouri A, Lurie AA. Concise review: methemoglobinemia. Am J Hematol. 1993;42:7–12.

Endre ZH, Charlesworth JA, Macdonald GJ, et al. Successful treatment of acute dapsone intoxication using charcoal hemoperfusion. Aust N Z J Med. 1983;13:509–12.

Dawson AH, Whyte IM. Management of dapsone poisoning complicated by methaemoglobinaemia. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1989;4:387–92.

Goldstein BD. Exacerbation of dapsone-induced Heinz body hemolytic anemia following treatment with methylene blue. Am J Med Sci. 1974;267:291–7.

Drori-Zeides T, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, et al. Practical guidelines for vancomycin usage, with prospective drug-utilization evaluation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:45–7.

Gerding DN. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;250:127–39.

da Cunha A, Weisdorf D, Shu XO, et al. Early gram-positive bacteremia in BMT recipients: impact of three different approaches to antimicrobial prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:173–80.

Chiosis G, Boneca IG. Selective cleavage of D-Ala-D-Lac by small molecules: re-sensitizing resistant bacteria to vancomycin. Science. 2001;293:1484–7.

Veien M, Szlam F, Holden JT, et al. Mechanisms of nonimmunological histamine and tryptase release from human cutaneous mast cells. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1074–81.

Polk RE. Anaphylactoid reactions to glycopeptide antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:17–29.

Hassaballa H, Mallick N, Orlowski J. Vancomycin anaphylaxis in a patient with vancomycin-induced red man syndrome. Am J Ther. 2000;7:319–20.

Brummett RE. Ototoxicity of vancomycin and analogues. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26:821–8.

Bhatt-Mehta V, Schumacher RE, Faix RG, et al. Lack of vancomycin-associated nephrotoxicity in newborn infants: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E48.

Cantu TG, Yamanaka-Yuen NA, Lietman PS. Serum vancomycin concentrations: reappraisal of their clinical value. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:533–43.

Christie DJ, Van Buren N, Lennon SS, et al. Vancomycin-dependent antibodies associated with thrombocytopenia and refractoriness to platelet transfusion in patients with leukemia. Blood. 1990;785:518–25.

Domen RE, Horowitz S. Vancomycin-induced neutropenia associated with anti-granulocyte antibodies. Immunohematology. 1990;6:41–3.

Somerville AL, Wright DH, Rotschafer JC. Implications of vancomycin degradation products on therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with end-stage renal disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:702–7.

Wrishko RE, Levine M, Khoo D, et al. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and Bayesian estimation in pediatric patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2000;22:522–31.

Lamarre P, Lebel D, Ducharme MP. A population pharmacokinetic model for vancomycin in pediatric patients and its predictive value in a naive population. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:278–82.

Wallace MR, Mascola JR, Oldfield EC. Red man syndrome: incidence, etiology, and prophylaxis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:1180–5.

Appel GB, Given DB, Levine LR, et al. Vancomycin and the kidney. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;8:75–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Grading System for Levels of Evidence Supporting Recommendations in Critical Care Toxicology, 2nd Edition

Grading System for Levels of Evidence Supporting Recommendations in Critical Care Toxicology, 2nd Edition

-

I

Evidence obtained from at least one properly randomized controlled trial.

-

II-1

Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization.

-

II-2

Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one center or research group.

-

II-3

Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention. Dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments (such as the results of the introduction of penicillin treatment in the 1940s) could also be regarded as this type of evidence.

-

III

Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies and case reports, or reports of expert committees.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing AG

About this entry

Cite this entry

Rangan, C., Clark, R.F. (2016). Rifampin, Dapsone, and Vancomycin. In: Brent, J., Burkhart, K., Dargan, P., Hatten, B., Megarbane, B., Palmer, R. (eds) Critical Care Toxicology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20790-2_60-1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20790-2_60-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20790-2

eBook Packages: Springer Reference Biomedicine and Life SciencesReference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences