Abstract

The author begins this essay with recognition that educators bring their own visions of subject matter, of children, and of the larger world, into the tasks of curriculum development and teaching. These visions come through a filter of personal values, which are often illustrated in the stories educators tell themselves and others, so examining those stories can be a way to heighten awareness of values. The author suggests, however, that awareness is insufficient if one is to go beyond the habitual to the intentional in professional practice, and that teachers need to question their beliefs, recognizing their limitations as well as their possibilities. To exemplify this process, the author shares stories that reveal some of her own visions—of dance, of young children, of the world and people in it—and how these visions have given rise to what and how she teaches. She also explores limitations to her visions and internal conflicts in the values underlying them, noting that sometimes reflection affirms one’s current practice and its underlying beliefs and sometimes it challenges them; even when challenged, it may take a while before one knows how to respond. The author concludes by acknowledging the value of professional development in which educators can share and examine their own stories.

An early version of this chapter was published in Visual Arts Research, 25 (2), 1999, 69–78.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

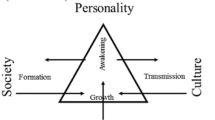

Teacher education students in methods courses learn to teach according to rules provided by other people. Once in their own classrooms, however, teachers sort through those rules, deciding which ones to keep and which to discard or replace with their own. While most teachers are still subject to guidelines and curricula provided by their employers, I find a lot of validity in the truism, “What we teach is who we are.” Who we are incorporates how we see the world (including those parts of it we call the curriculum), what we know of children, what we think about teaching and learning. These visions come through a filter of our values—what we believe in, how we want to live our lives in relation to children. One way to become aware of our values is to look at the stories we tell. Just as myths and legends embody cultural understandings, and treasured family stories give evidence of what a family values, we each as teachers have stories that exemplify our beliefs. When we look at our stories, we come to recognize what we know and value.

But recognizing our values and visions is not enough if we are to go beyond the habitual to the intentional in teaching. We also need to question our beliefs, to recognize their limitations as well as their possibilities. In other words, I believe that we should teach who we are only if we are willing to engage in ongoing questioning, reflection, and commitment to growth. Without such questioning, teaching who we are can mean ignoring the needs of our children and the context of our communities.

To exemplify this process, in this paper I will share stories that reveal some of my own visions—of dance, of young children, of the world and people in it—and how these visions have given rise to what and how I teach. Many of the stories about children are about those I know best, my own children. (This, of course, presents its own limitation, which I shall discuss later.) I will also raise issues or questions with each piece of my vision. In this process, I am using myself only as an example; my visions are no more important than anyone else’s. What is important is not my personal vision, but the reflective process that brings to consciousness our values and how they translate into what and how we do and do not teach.

1 Vision of Dance

One definition of dance is rhythmic movement, usually done to music. Certainly the impulse to move rhythmically is a powerful one; most of us have a strong urge to tap a foot or clap our hands when we hear rhythmic music. I remember how surprised I was when I had my first job working with day care mothers and their infant charges, to discover that babies only a few months old may bounce to music with a strong beat. I am still charmed at outdoor concerts to see toddlers get up and unselfconsciously bounce and sway. As noted in the recent guide on Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Movement Programs for Young Children (1995) by the Council on Physical Education for Children (COPEC), good movement programs give young children opportunities to move rhythmically, finding their own ways to do so.

1.1 Conscious Awareness

However, my vision of dance, now informed by many years of varied experiences, goes further than rhythmic movement. I remember my first teaching experience, when my supervisor came to observe after I had been working with a group of rather unruly youngsters for several sessions. Following the lesson, she told me as gently as possible about her mentor, renowned dance educator Virginia Tanner, who was able to get even very young children to not only move creatively, but also dance. That sent me on a journey of many years, trying to figure out what makes the difference between dancing and just moving.

One key insight I found in study with dancer and choreographer Murray Louis. I ask the reader to do the following activity, adapted from Louis, rather than just read it:

First reach up and scratch your head; then return your arm to your lap. Next, choose a part of your arm that can initiate a reach; it could be fingertips, wrist, elbow, or shoulder. Starting with that part, begin extending your arm. Continue to a full extension, then past the point where your arm is straight, so that it is stretched, and the stretching energy comes out your fingertips. Now redirect that energy back toward your head, and condense the space between your hand and head, until your fingertips are just barely resting on your scalp.

You have just done a dance.

As this example reveals, dance is not what we do, but how we do it. It is a state of consciousness involving full engagement and awareness, attending to the inside.

When I reflect upon this definition of dance, I sometimes question whether it is appropriate for young children. Often, when I observe movement and dance activities for young children led by other teachers, they seem to be primarily about getting the children to move and to make their own movement choices. I value both of these goals, but by themselves they do not make dance. In my definition, the aesthetic experience of dancing can only come when we move with concentration and awareness; it is this which transforms everyday movement into dancing. But I sometimes question whether I may be allowing my own personal desire for aesthetic experience to take priority over the needs of children. In a later section of this paper, I will reflect further upon this issue as part of my vision of young children.

While listening to my concerns, I have worked to find ways to enhance the ability of young children and older ones to go beyond just doing the movement. This has involved “teaching to the inside,” helping students become aware of what movement and stillness in different positions feel like on the inside. I can teach children by age eight or so about their kinesthetic sense, and how it works to tell them what their body is doing without their looking. With preschoolers, very simple experiences can help develop this awareness. For example, we shake our hands for about 10 seconds, then freeze them, noticing how they still tingle on the inside. A young child once told me this feeling was “magic,” and I often use this description in teaching others. I teach the children that our dance magic lives in a calm, quiet place deep inside us; most seem not only to understand, but to already know this. We make a ritual of sorts at the beginning of the class, finding our “dance magic,” and I try to use language and images throughout the class to help children not only move, but feel the movement. When we start to lose the concentration this takes, we take a break and intentionally do something that is “not magical,” so that children will develop their awareness of when they are dancing and when they are just moving.

1.2 Form

One other piece of my vision of dance that I share with young children has to do with what adults call form. Just as humans have an impulse to move rhythmically, we also have an impulse to give form and order to our perceptions and experiences. For example, adults have organized perceptions of differences throughout the age span into what we call stages of development. Similarly, we organize movement into games and dances.

Story form, with its beginning, middle, and end, is often used for organizing our experiences. I recently spent a week at the beach, all too close to where hurricane Bertha (the main character of this story) was also in residence. Bertha’s presence ensured that we spent less time on the beach and more time watching the Weather Channel, and many nearby attractions were closed for part of the week. However, our vacation was not a complete loss. Bertha gave our week a sense of high drama, and offered us an opportunity to tell an exciting story upon our return. The story began as we were carefree and ignorant of Bertha’s presence. Tension rose with our discovery that we were under a warning. The peak of the crisis came at 11 pm one night, when Bertha suddenly changed course and headed toward us; we packed our bags to prepare for what appeared to be an imminent mandatory evacuation. The tension resolved when Bertha shifted still again, and the story ended in relieved sunshine.

While some dances have very complex form, the most basic concept of dance form is understandable to preschoolers: A dance, like a story, has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Usually in preschool, we begin and end dances with a freeze (stillness), so that the dance is set off from movement that is not part of the dance. This reinforces John Dewey’s (1934) concept of art as experience—he describes “an experience” as being set off in some way from the stream of the rest of the world going by.

Dewey’s definition of “an experience” goes far beyond the simple perception of beginning, middle and end; his description of aesthetic form includes many aspects beyond the cognitive level of preschoolers. We do not expect a dance made by a preschooler to be complete in and of itself, with parts that flow together to make a whole; we do not expect both unity and variety, internal tension and fulfillment. But many of these conditions which make a good work of art also make a good dance class, even for preschoolers.

Just as many stories begin with “Once upon a time,” a beginning class ritual focuses children’s attention and prepares them for what is to follow. In my preschool classes, we do focusing activities to begin. A class gets unity from a theme; I use something from the real or imaginary world of young children, such as thunderstorms or toys, or a story, to provide the theme. Within the theme, I take different ideas, such as clouds, thunder, and lightning, or bouncing balls, floppy dolls, and mechanical toys, to provide variety. We translate each of these ideas into movement, finding, for example, which body parts can bounce, and how to “throw” oneself to a new spot by jumping.

Making parts of a class flow together is always part of my plan. For example, in a class on autumn leaves, I might ask the children to let the wind blow them back to the circle so that we can continue with what comes next. I also plan for a real ending to each class, something that brings closure and also leads into a transition to the next activity of the day.

I admit that lessons with preschoolers do not often go exactly as planned, and there are many opportunities for improvisation, another skill I learned as a dancer. But in many ways, planning and teaching my classes feels to me like a form of art-making, an idea for which Elliot Eisner (1985, 1987) is well known. He encourages us to think of evaluating teaching much as we do works of art, and encourages educational “connoisseurship” and criticism.

Sometimes when I finish teaching a class, there is that wonderful satisfaction of knowing that all the parts have come together seamlessly to create a real whole, and a shared transcendent experience has taken place. Even though such experiences occur less often for me with younger children, they are ones to cherish. As Madeline Grumet (1989) points out, it is all too easy to become seduced by a “beautiful class.” We need also to maintain our critical faculties, and consider both the gains and losses of thinking about such classes as the peak experience of teaching. I have to ask myself whether the transcendent experiences mean anything in the long run, or whether they are just feel good moments that keep us engaged so we can persevere to what is really important. And what is really important is often as messy as a preschooler’s play area, leaving considerable ends that are not neatly tied up into an aesthetic whole.

2 Vision of Young Children

Adults used to think that children were simply miniature adults. Now prospective teachers of young children are taught about distinct developmental differences. These are most often framed in terms of those things young children cannot do (and should not be expected to do), when compared with older children and adults. For example, we do not ask them to sit still for very long or to learn multiplication tables. We assume that young children will get “better,” i.e., more like us, as they develop. I have reflected elsewhere (Stinson 1990) on my concerns over how a developmental model limits our thinking about important qualities that young children possess that all too often disappear as they grow up in our culture.

In this section, I will discuss three aspects of early childhood that are not always mentioned in early childhood texts but have made significant contribution to my choices of content and methodology: their capacity for engagement, their impulse toward creativity, and their drive to develop skills and become competent.

2.1 The Capacity for Engagement

Many of my undergraduate students have a vision of young children that I used to share: the idea that young children have a short attention span. My experiences with young children have taught me that sometimes their attention span far exceeds that of an adult. (I certainly tired of reading the classic children’s story Madeline (Bemelmans 1939) every night long before my daughter did.) While they are usually less willing than adults to stay with an activity in which they are not engaged, most young children have the capacity for significant engagement. For example, one day I was talking with a friend and colleague about her dissertation (on creativity in children) while our children, then four and five, played in a back room. When we finished we went back to the playroom, but stopped at the door. Ben and Sarah were engaged in pretend play, in fact, so engaged that they did not notice when we came to the door. My friend and I stood there for several moments before we tiptoed away. It was as though our children had created something sacred; we were not part of it, and we could hardly have walked in at that moment and said “It’s time to stop now” any more than we could have walked into a religious service or any other sacred activity. This story exemplifies for me how children can engage so fully that they seem to be in another world.

I also remember my daughter at age 2½, when I took her into a partially lighted theater on my way to what was then my office; she looked around at the collection of stage sets and props, and whispered, “Does Santa Claus live here?” How many times children notice the extraordinary moments that we miss: the rainbow in the puddle, the trail of ants, the sound of grass growing. It may require great patience for us as adults to allow children to be engaged.

I think this capacity is worth cultivating. If we are always disengaging young children from what calls them, is it any wonder when they learn not to get too involved, and then we eventually berate them for their lack of concentration?

An appreciation for the capacity for engagement has had a great impact on my teaching, particularly as it has come together with my previously discussed vision of dance. COPEC’s guide (1995) to developmentally appropriate practice notes that teachers of young children should serve as guides and facilitators, not dictators; this implies a child-centered curriculum, which I think facilitates engagement. We need to make sure that children have choices, and have opportunities to move and dance during free play, not just during instructional time. We need to follow as much as lead, help them discover their interests, appreciate their creations, and give them the respect of our full attention. Young children also give us very clear signals regarding when to stay with an activity and when it is time to move on; we need to attend and respond to them.

Eventually, of course, schoolchildren will be asked to concentrate on the things that interest teachers, not only the things that interest themselves. This presents many dilemmas to those of us who see how engaged young children are in their own learning and how disengaged most adolescents are. How much of this change reflects normal development, and how much comes from asking students to leave their interests behind for those things adults consider worth learning? How much should teachers prepare young children for the teacher–and subject–centered schooling that will come, and how much should they allow learning to be child-centered? If school were entirely student-centered, would this only encourage self-centeredness? I know too many adults who only want to do the chores they find interesting, leaving the boring work to partners or colleagues.

Even more troubling in regard to this part of my vision for young children is my recognition that deep engagement does not come readily to all young children. I remember my daughter’s 5-year-old friend, who was so hyperactive that he entered our house by attacking it, and within minutes something was broken. Eventually I decided that this child would need to be an “outside friend,” and I planned visits to a nearby park in order to allow the friendship to continue. While he was the most extreme example I have encountered, I have met many other children in my classes who had difficulty finding their “calm quiet place inside,” and certainly could not remain there for very long. They are readily identifiable as “zoomers,” who would spend an entire dance class running through space if that were possible. These children remind me to include vigorous, challenging movement throughout the class, with quiet moments as contrast. A freeze after sudden shape changes or shaking a body part allows us to notice ourselves in stillness. I try to start “where the children are,” and gradually move with them from frenzied activity toward calm engagement. But I still question whether my cherishing of the calm center is a reflection of my own need, and my carefully developed techniques to facilitate engagement and inner sensing of the movement a way to manipulate children.

2.2 The Importance of Creativity: “I Made It Myself”

When children tell me, “I made it myself,” or “I thought of it myself,” I am reminded how important it is for young children to see themselves as creators, as makers, as inventors. My son was a sculptor; he pulled all the toilet paper tubes, cereal boxes, scraps of wood, rubber bands, string, and everything else out of the trash can for his constructions before I learned from him, and started not only saving everything but also soliciting from my friends. One year his Christmas stocking held eight rolls of masking tape, a supply which did not even last a year. When we ran out of room to store his constructions, I took pictures of them to save. I wanted him to know how much I valued his original creations.

I try to give young children many opportunities to be creators: to make their own shapes (not just imitate mine), to find new ways to travel without using their feet, to invent a surprise movement in the middle of a backwards dance. As they become more skilled, they take on greater responsibility for creation. At this point, children are not only making choices within structures I provide, but actually creating the structures.

Martin Buber called this impulse toward creativity the “originator instinct,” and wrote, “Man [sic], the child of man, wants to make things….What the child desires is its own share in this becoming of things” (1965, p. 85). But Buber’s questioning of the creative powers of the child as the primary focus of education led me to do the same. Buber concluded that “as an originator man is solitary….an education based only on the training of the instinct of origination would prepare a new human solitariness which would be the most painful of all” (p. 87). He reminds me that creativity alone does not lead to “the building of a true human life”; for such a goal, we must experience “sharing in an undertaking and…entering into mutuality” (p. 87). As I will discuss shortly, I find it challenging to try to find ways to educate young children, who often have great difficulty understanding even the concept of sharing, into mutuality.

I am also aware of the current focus of arts education in areas other than creativity. The Getty Center, in a work entitled Beyond Creating (1985) and in many others since, has informed arts educators that too much emphasis had been placed upon creativity and production, and too little upon history, criticism, and production. Elliot Eisner (1987) emphasized that art should be thought of as a cognitive activity, rather than an emotional one, and even some early childhood arts educators are writing that young children should spend more time looking at and responding to art made by adults, which implies less time making their own. Anna Kindler (1996) criticizes any “hands off” curriculum that just allows children to create, believing that just creating is not enough stimulus for children to develop cognitive skills.

I continually question whether my vision of the young child’s impulse toward creativity is some mere romantic notion that is hopelessly out of date. I also know that I gave up the idea that children needed only opportunities to dance, and no instruction, when I decided to become a dance educator. My career has been spent developing ways to help children go beyond where they might be “naturally,” without dance education. But my vision of the young child’s impulse to create is still strong.

2.3 The Importance of Competence: “I Did It”

A third piece of my vision has to do with the importance of competence, of being skillful, in young children’s self-esteem. My son at the roller skating rink gave me one of many stories that exemplify this perception. His style of learning to skate involved leaning way forward, then going as fast as he could to get as far as possible before falling down. Etched forever in my memory is the first day he made it all the way around the skating rink without falling, and how he crowed, “I did it!!” We need to give young children many opportunities to say, “I did it,” and gain the pride that comes with such achievements. To me, this means opportunities to go beyond what they can already do—not too far beyond, of course, because that generates the kind of frustration that can make children give up. But those of us who appreciate children so much as they are need to remember that no one shouts “I did it” when the task has not been a challenge.

It took me a fairly long time to recognize the importance of movement skill, what dancers refer to as “technique,” for young children. Like many other teachers enamored of creative dance, I wanted to preserve what I saw as the “purity” of children’s natural expressiveness in movement, and not spoil it by teaching them technique. Eventually I realized that children are learning from adults, and imitating us, from a very early age; this learning includes movement skills. We have to choose not whether to teach children skills, but which ones and how we will teach them. I know that children can still feel good about themselves when they learn by imitation; this is how they learn to tie their shoes, which they always seem to view as a great accomplishment. I have also seen the pride felt by a 3-year-old in demonstrating a ballet step, no matter how poorly.

Yet I still find myself led toward exploration more than imitation, finding that a sequence of exploring/forming/performing is useful in developing movement skills as well as creative work. For dance technique, exploring possibilities (such as the differences between a bent, curved, straight, and stretched arm) is important in building the kinesthetic awareness necessary if performance of movement is to be not only correct but expressive.

I also find myself interested in basic movement skills more than codified dance steps. These skills are the kind that children will use in all dance forms and other movement activities. These include how to run or jump or fall without making a sound, how to move close to another person without touching, how to stop oneself (which is hard if one has been moving fast), how to swing oneself around in a turn, how to make points and curves with an elbow. Exploring these kinds of activities will help children become more skillful movers in any dance form they may choose when they become older, and will help them become people who say “I did it!” in the present.

Back in my reflective mode, I look through my first-born’s baby book and see more dates of achievements than stories: crawling, pulling up to standing, first steps, shinnying up a flagpole, going hand-over-hand on the horizontal ladder, tying her shoes, riding a two wheeler. Sometimes I could not sort out her pride from my own, thinking that I proved I was a good mother by my child’s accomplishments. I think sometimes teachers make the same error, seeing a child’s accomplishments mostly as a reflection of our own competence as teachers. It is humbling to realize how many skills young children will develop without formal instruction, as long as they have opportunities that include safe and appropriate space and equipment, time to explore, and an adult who notices and encourages.

When I reflect now, I have to ask the same question my daughter asked me at age three, when I told her I was going to teach a dance class: “Why do you have to teach people to dance?” Another time, when someone asked her if she planned to be a dancer when she grew up, she replied, “I already am.” Dance educators are fond of saying that everyone is a dancer, whether they know it or not. I wonder whether dance teachers would be needed for young children if our culture were one in which everybody danced, and knew they were dancers. In such a culture, at what level might a need for instruction be felt by a child?

As I continue to reflect upon issues raised in my previous discussion of creativity, I am aware that the only skills I have mentioned are psychomotor ones. What about the cognitive skills that the Getty Center and others are so concerned about developing? Certainly an inability to read or write is likely to be more damaging to a 7-year-old’s self-esteem than an inability to ride a bicycle or to dance. I do think we should be expanding young children’s vocabularies for describing dance, and I took my own children as preschoolers to every dance performance suitable for them, encouraging them to name and respond to what they saw. But there were not many of these, and there are very few dance videos that can hold the attention of most young children for very long. There seem to be far more adult created works in visual art, theater, and music that are appropriate for young children.

I am also convinced that children learn dance concepts better through movement than through looking at other people dance, especially in early childhood and in students of all ages who are kinesthetic learners. Even when I ask young children to watch me demonstrate, for example the difference between low and high levels, most of them automatically move along with me while they are watching. But I wish there were more opportunities for young children to see people other than their peers perform, and I continue to encourage those few choreographers who make performances for children to consider making videos as well. I wonder what kind of aesthetic education in dance might be possible if more suitable materials were available.

2.4 Reflections on My Vision of Children

For a number of years, I have taught developmental stages to my students through stories, theirs and mine. While the students have voiced appreciation for this approach, I have realized its potential limitation: Whose stories do we tell? Because my students are, like myself, primarily white middle class women, if we only collect our own stories, we are simply reinforcing what I have heard called the prison of our own experience. I continue to seek experiences for myself and my students that will allow us to expand our prisons, knowing that we can never escape them completely.

3 Vision of the World and People in It

I remember a Sesame Street book one of my children had, about Grover and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum (Stiles and Wilcox 1974). Each room in the museum was different: Imagine a room filled with tall things, another with small things, another with red things, or scary things. After going through room after room, one finally came to the last door, which led to “everything else in the whole wide world,” and Grover left the museum. My vision of the world is filled not with things but with ideas or principles; I will share two of them.

3.1 Individuality

The first piece is about individuality: Each person is unique and special. I often begin teaching dance to a new group of young children by showing a collection of geodes. On the outside, they look plain and ordinary. But on the inside, each one is different and special and magical. As I tell children, so are they. This kind of appreciation of differences is an essential part of a preschool dance class. My belief in the importance of individuality is another reason to encourage each child to find her own way, his own shape. Because young children often imitate each other as well as adults, we usually have to give additional encouragement to generate differences. But children in any creative dance class learn early on that the teacher values invention more than imitation.

I have already raised Martin Buber’s concern about the temptation to place too much emphasis on individualism in education when we think about creativity. We also have to remember that images of individuals are constructions deeply imbedded within our own culture. (See Martin 1992, for a particularly thoughtful discussion of these images in American literature.) But there are other concerns as well about an overemphasis on individuals doing their own thing. I recall an incident when I first offered creative dance classes for preschoolers at what was primarily a ballet studio. One parent who had come to sign up her 3-year-old told me angrily that her daughter needed to develop discipline, not creativity; her child apparently climbed on the dining room table to perform, an act the mother did not appreciate.

But I think that another part of individuality that I want to cultivate in the world and in dance is the responsibility for self-management. I remember one particularly challenging second grade class that I taught. After two sessions that came close to bordering on chaos, I devoted an entire lesson to “controlling your own energy.” This class was held the week after a major hurricane had occurred, and I was able to use this as an example of how destructive energy can be when it gets out of control. Bordering on desperation, I even told them that children who could not control their own energy get sent to the principal’s office, while adults without control get sent to jail. Since the positive side of the message was that controlling our own energy allowed us to make things instead of destroying them, we then spent the rest of the class exploring three kinds of energy—strong and sharp, soft and sustained, and exploding—in order to make a dance about a storm. I concluded that this was probably the most important lesson I taught them.

The concept of the “inner teacher,” which I absorbed from two years of teaching in a Quaker school, has also encouraged me to think of self-management as an aspect of individuality. Even with preschool children, I give opportunities to “be your own teacher, tell yourself what to do” during a class. If all children could find their inner teacher, think how different schools would be.

3.2 Connectedness

Another part of my vision has to do with the connectedness of all these diverse individuals, what some feminist theorists refer to as a web of relations. Our experience of connectedness begins at birth; we are born connected to another person. Beyond ties of birth, however, we usually think of connections as something we must create, with an assumption that things and people are basically separate; we have to find ways to bring them together like pieces of a child’s construction set.

But my experience in dance has taught me that a great many connections exist outside our awareness of them. We do not have to create these connections, but simply become aware of them and use them in moving and thinking. For example, I have spent many hours in dance classes lying spread-eagled on my back, finding the diagonals that exist in my body, so that movement initiated by the right hand and arm results in movement by the left leg and foot, conveyed through the center of the body.

I am convinced that, just as our bodies are held together by internal connections, we are connected to others by ties that are sometimes as difficult to see as our own ligaments buried beneath layers of skin, muscle, and fat. I have also been moved by Buber’s (1958) consideration of connection: When we recognize our connectedness, we become responsible for that to which we are connected. If we recognize our connections with others, we become responsible for them; this is critical in a world in which peoples are fragmented and at war. It is also critical to recognize our relationship with, and responsibility for, the earth.

Originally spurred by Buber’s call toward community, I have spent many years seeking ways to enhance community building among my students. For me, this gets far easier beyond early childhood. I find it challenging to teach relationship skills to young children; their egocentrism means that they are not ready for most partner and group work that could facilitate dance relationships. With preschoolers, I find it easier to teach lessons that deal with relationships between themselves and the environment and/or human-made objects in the world. Ideas for classes come from the imaginary and real worlds, not just from movement words like rise, turn, and sink, and abstract concepts such as high, low, fast, and slow.

For example, imagine for a moment some of the things from the everyday world that go up, turn, and come down. For the most part, when I construct dance classes with children, it is about things they care about which have shapes and/or move. My first thoughts usually go to the natural world, because I feel such a strong connection with the earth, and I want to share that with children. So autumn leaves might get picked up by the wind, turn, and fall back down. Or a bird might go into the air, circle a tree, and come back to the nest. The sun rises, shines over all the earth, sinks. The largest number of my class themes came from nature until one time I was asked following a conference presentation, “What about those urban children who do not have much opportunity to experience nature?” That question led me to expand my themes; airplanes and helicopters, as well as helium balloons, can also go up, turn, and come down.

I must note that, despite the use of themes that can easily be personified, I do not ask children to pretend to be anything other than who they are: dancers. Instead, I ask them to try on the qualities they share with whatever we are dancing about. Although some will transform themselves into leaves or birds or helicopters, I prefer to let a child’s pretendings belong to them.

In my reflective mode, I still feel concerned that I do little to facilitate the development of community among preschoolers. While I do this more with primary grade children, I have little success even getting children to work successfully in partners until the third or fourth grades. At one point I smugly thought I was merely being developmentally appropriate. Now, I read of others teaching cooperative learning techniques to young children, and I wonder why I am so rarely successful in having young children sensitively mirror a partner, unless that partner is an older child or adult.

4 Conclusions

Taking the opportunity to think about meaningful moments in our lives, those that come to exemplify something we believe, helps us become more conscious of our visions and values. Asking ourselves questions about our values and visions gives us the opportunity for professional growth. Sometimes reflection affirms our current practice and its underlying beliefs, and sometimes it challenges them. Even when challenged, it may take a while before we know how to change what and how we teach.

Yet teachers of young children are busy people, with far fewer opportunities than college professors have to reflect on their values and visions. My hope is that professional development for early childhood educators might provide not only workshops for teachers to learn new skills (such as teaching movement and dance), but also opportunities to share and to question the stories of their lives that guide their professional practice.

Commentary

This chapter was written at the kind invitation of Liora Bresler, co-editor of the volume in which it first appeared. I am grateful to Liora for her consistent encouragement for me to write in my own voice. Most of the work I have written about young children is practical, rather than theoretical, including my 1988 book written for teachers of this age student. This chapter, in contrast, gave me more opportunity to reflect, to question my own values and visions and how I was attempting to live them, as well as becoming aware of their limitations. In preparing this volume, I notice that this chapter, grounded in my own experiences with young children, makes little use of scholarly references, even in my critical reflections on those experiences. It also contains little reference to issues of social justice, which underlie most of the other chapters in this section. I alluded to this absence when I acknowledged the limitation of examining only our own stories. My research listening to middle and high school students, referred to elsewhere in this volume, gave me stories that brought me in touch not only with joys they found in dance, but with the pain many were experiencing in other parts of their lives; it was a significant factor in expanding my consciousness. Similar stories from young children are not part of my direct experience, and indeed the inability of so many young children to speak for themselves means that it is easier to remain ignorant of their suffering, until we read occasional stories in the media. At the end of my career, I am humbled by this realization and hope others in arts education will fill in this gap in the future.

References

Bemelmans, L. (1939). Madeline. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou (2nd ed.) (R. G. Smith, Trans.). New York: Charles Scribner’s.

Buber, M. (1965). Between man and man (M. Friedman, Trans.). New York: Macmillan.

Council on Physical Education for Children (COPEC). (1995). Developmentally appropriate practice in movement programs for young children, ages 3–5. Reston: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Minton Balch.

Eisner, E. W. (1985). The educational imagination (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Eisner, E. W. (1987). The role of Discipline - Based Art Education in America’s schools. Los Angeles: Getty Center for Education in the Arts.

Getty Center for Education in the Arts. (1985). Beyond creating: The place for art in America’s schools. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust.

Grumet, M. R. (1989). The beauty full curriculum. Educational Theory, 39(3), 225–230.

Kindler, A. M. (1996). Myths, habits, research, and policy: The four pillars of early childhood art education. Arts Education Policy Review, 97(4), 24–30.

Martin, J. R. (1992). The school home: Rethinking schools for changing families. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stiles, N., & Wilcox, D. (1974). Grover and the everything in the whole wide world museum. New York: Random House.

Stinson, S. W. (1988). Dance for young children: Finding the magic in movement. Reston: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance.

Stinson, S. W. (1990). Dance and the developing child. In W. J. Stinson (Ed.), Moving and learning for the young child (pp. 139–150). Reston: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stinson, S.W. (2016). What We Teach Is Who We Are: The Stories of Our Lives (2002). In: Embodied Curriculum Theory and Research in Arts Education. Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education, vol 17. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20786-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20786-5_6

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20785-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20786-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)