Abstract

Since 2007, no scientific body of national, or international, standing rejects the findings of human-induced climate change. Yet in the United States, public opinion and public policy remain deeply divided on the issue. I review five longitudinal surveys from Yale/George Mason, Stanford/Resources for the Future, University of Michigan/Brookings, Gallup, and the Pew Research Center to understand different surveys of Americans have different results to the question “Does global warming exist?” I find that question wording makes a difference, and researchers may want to focus their efforts on answering the questions that lead to the “Don’t know” responses.

This chapter was created within the capacity of an US governmental employment. US copyright protection does not apply.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The vast majority of scientists and researchers agree that man-made emissions are likely exacerbating climate change ; since 2007 no scientific body has disagreed with this position (Oreskes 2007). However, it is clear from US news articles to the contrary (e.g., Taylor 2013) that Americans remain deeply divided on whether anthropogenic climate change exists. As this makes many forms of climate change legislation nearly impossible to achieve a bipartisan consensus, this begs further study into how and why respondents answer “Is global warming happening?”

2 Background: A Snapshot of Current Beliefs

To begin to understand the breadth of the disagreement, we examined news headlines from June 2014. The following three articles presumably were generated in response to the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) June 2, 2014, proposal to regulate utilities’ greenhouse gas emissions (EPA 2014). First, in New York Times, “Is Global Warming Real? Most Americans Say Yes” suggests that most Americans believe in global warming (Kopicki 2014). Second, the Washington Post/ABC News in “Broad Concern about Global Warming Boosts Support for New EPA Regulations” is more lukewarm, but still suggests that most Americans are in favor (Langer 2014). Third, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s “Pennsylvania voters favor EPA greenhouse gas curbs, poll shows” also shows that that Americans believe in global warming (Hopy 2014). Based on these headlines, it would seem clear that the majority of Americans believe global warming is real and support regulation of greenhouse gas emissions.

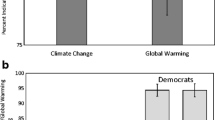

Then let’s take a longer-term perspective to try and better understand what Americans really think. Figure 4.1 shows America’s response to Stanford University, Yale University/George Mason, the Pew Research Center, the University of Michigan (previously Brookings), and Gallup polls asking basically the same question: “Is global warming happening?” While the differences among polls likely occur due to question wording, one stark realization stands out. Since 2006, a majority (50–85 %) of Americans have agreed that global warming is happening, but there is also variance among those numbers. This variance is likely sufficient to influence policymakers’ actions, particularly when broken out on a state, regional, or congressional district level.

Percent of total American public answering “Yes” to the question “Is global warming happening?” Top: Where possible, interpret loosely, as in “Temperature may already have or may in the future warm; no causal attribution.” Bottom: Where possible, interpret strictly, as in “Temperatures have been increasing; this is at least partially caused by man.” The vertical bars give the polling error indicated by the survey authors (Sources: Yale (Leiserowitz et al. 2012a, b, c, 2013, 2014), U Michigan/Brookings (Borick and Rabe 2012a, b, 2013, 2014), Stanford (Krosnick and MacInnis 2011; Krosnick 2012; Jordan 2013; Harrison 2013; Resources for the Future 2014), Gallup (Saad 2012, 2013, 2014), and Pew (2011, 2012, 2013, 2014))

3 Grounding the Problem: Understanding the Responses

To better understand why the different polls fail to agree, I decided to look more closely at the wording in each survey. Table 4.1 gives a breakdown of the slightly different slices of “Is global warming happening?” that each survey asks for, and the subsections below give more detail about each question. For each survey, I highlight the answer to the question “Is global warming happening?” in the text and in Fig. 4.1. If the option is given, I interpret this in two ways:

-

1.

Loosely Where possible, interpret as “Temperature may already have or may in the future warm; no causal attribution.”

-

2.

Strictly Where possible, interpret as “Temperatures have been increasing; this is at least partially caused by man.”

3.1 Stanford

Stanford Woods Institute Senior Fellow Jon Krosnick has been conducting public opinion studies on climate change and related efforts since at least 2006 (Krosnick and MacInnis 2011; Krosnick 2012; Stanford 2013; Harrison 2013; Jordan 2013). Now run by Stanford University’s Political Psychology Research Group (Resources for the Future 2014), this survey question continues to be run roughly every year:

- Q::

You may have heard about the idea that the world’s temperature may have been going up slowly over the past 100 years. What is your personal opinion on this—do you think this has probably been happening, or do you think it probably has not been happening?

- A::

Has been happening, Has not been happening, Don’t know/refuse?

The values we report in Fig. 4.1 are the “Has been happening” (73–85 %); approximately 2–3 % of respondents typically answer “Don’t Know/ refuse.” The percentage point error is between ±3 and ±5 depending on the number of respondents for each survey. Likely, this has the highest value of “yes” for all the polls because it emphasizes a slow change over the last century and uses the word choice “probably.”

3.2 Yale/George Mason

The Yale Project on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication have successfully collaborated for several years on this question (Leiserowitz et al. 2012a, b, c, 2013, 2014). The 2014 PIs, Anthony Leiserowitz, Geoff Feinberg, Seth Rosenthal, Edward Maibach, and Connie Roser-Renouf, have asked roughly twice a year:

- Q::

Recently, you may have noticed that global warming has been getting some attention in the news. Global warming refers to the idea that the world’s average temperature has been increasing over the past 150 years, may be increasing more in the future, and that the world’s climate may change as a result. What do you think? Do you think that global warming is happening?

- A::

Yes, No, Don’t Know.

The values we report are the “Yes” (61–71 %); approximately 10–20 % of respondents typically answer “Don’t Know.” The percentage point error is between ±2 and ±3 depending on the number of respondents each survey. Similarly to the Stanford poll, this poll adds uncertainty by using “may,” so we would expect similar results. Unfortunately, this poll had a much higher response of “Don’t Know,” possibly due to the final phrase “the world’s climate may change as a result.” To compare the two, if you assume that half of all “Don’t Knows” would have answered “Yes,” this polling will then agree quite strongly with the Stanford finding.

3.3 Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center based in Washington, D.C., conducts nonpartisan, non-advocacy public opinion polling and demographic research. Regarding global warming (Pew 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014), it asks:

- Q::

Is there solid evidence the earth is warming?

- A::

Yes (because of human activity), Yes (because of natural patterns), Yes (don’t know), No, Mixed evidence/Don’t Know

The values we report are those answering loosely, “Yes (any answer)” (57–77 %), and those answering strictly, “Yes (because of human activity)” (34–47 %); approximately 6–10 % of respondents typically answer “Mixed evidence/Don’t Know.” The percentage point error is ±3. Likely, this falls in the middle of the pack because they ask respondents about “solid evidence,” as opposed to the first two polls that express high levels of uncertainty .

3.4 University of Michigan/Brookings

This poll was initially housed at Brookings as the National Survey of American Public Opinion on Climate Change (NSAPOCC) and is now run through University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy’s National Surveys on Energy and Environment (Borick and Rabe 2012a, b, 2013, 2014). There was no noticeable change when switch occurred in December 2011. They ask:

- Q::

Is there solid evidence that the average temperature on Earth has been getting warmer over the past four decades?

- A::

Yes, No, Don’t know

The values we report are the “Yes” (52–72 %); here again the “Don’t knows” are quite high at approximately 10–20 %. The percentage point error is between ±3 and ±4 depending on the number of respondents each survey. Likely, this falls lower because they ask respondents about “solid evidence” in the “past four decades,” as opposed to the first two polls that express high levels of uncertainty over a century or longer.

4 Gallup

Gallup has extensive experience running polls on just about any US policy question that exists. Of our surveys, they are the only ones to have consistently asked their question the same month (March) of every year since at least 2006 (Saad 2012, 2013, 2014). Specifically,

- Q::

Which of the following statements reflects your view of when the effects of global warming will begin to happen:

- A::

They have already begun to happen, they will start happening within a few years, they will start happening within your lifetime, they will not happen within your lifetime, but they will affect future generations, or they will never happen?

We report those who answered loosely, everything except “They will never happen” (81–92 %), and those answering strictly, “They have already begun to happen” (49–61 %). The percentage point error is ±4. We suspect there is a low response rate in this instance because the question didn’t ask about “global warming”; it asked about “the effects of global warming.” Also, this question has a much more specific timeline than the other questions.

5 Discussing the Effect of Demographics

Prior to interpreting these results, we must first ask whether the differences in response might be due to demographics of the respondents. It is a common practice in surveys to obtain a large enough respondent pool to include the views of the entire population and then weight particular responses to adjust the convenience sample into a true representative sample. In each of the surveys reported here, the researchers obtained sufficient participants (typically 1,000 or more) and then adjusted their results to reflect the entire United States. The uncertainty caused by this analysis is typically +/− 2 to 5 percentage points per response and reported in both the text and in Fig. 4.1. Since all of the surveys included have interpreted their results in this manner, the differences should not be due to demographics.

However, the question of demographics remains interesting. Consequently, many studies, including each of the five longitudinal studies referenced in this chapter, have examined respondent demographics. For instance, the Yale group has split their respondents into “Six Americas” with differing responses to whether global warming was real: alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, and dismissive (Leiserowitz et al. 2014). Each group has different demographics, including age, sex, race, and wealth. For instance, the “alarmed” group believes in global warming and is highly worried about the consequences. This group tends to be moderate to liberal Democrats who are women, older to middle aged, college educated, and of upper income levels. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the “dismissive” group tends to not believe global warming exists. This group tends to be high-income, well-educated, white men who are very conservative Republicans.

John Ramos (2014) examines whether education level affects the response. He used the 2010 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) asked over 50,000 respondents (CCES 2010):

- Q::

“From what you know about global climate change or global warming, which one of the following statements comes closest to your opinion?”

- A::

“Global climate change has been established as a serious problem, and immediate action is necessary,” “There is enough evidence that climate change is taking place and some action should be taken,” “We don’t know enough about global climate change, and more research is necessary before taking any actions,” “Concern about global climate change is exaggerated. No action is necessary,” or “Global climate change is not occurring; this is not a real issue.”

For this framing, education has little effect on views on climate change .

6 Lessons Learned

Given that each survey samples a demographically similar group of US citizens and therefore demographics are not causing the differences, the above analysis illustrates two points. First, question wording makes a difference in the polling results. For instance, recall we interpreted the question “Is global warming happening?” in the strictest sense possible: temperatures have been rising in the past and this is due to mankind’s activities. This may not be the same interpretation that others might use. For instance, the Stanford question is only about temperatures; someone who believes that temperatures are increasing, regardless of the reason, would answer “yes.” However, the Yale survey mentions global warming; a reader who believes temperatures are increasing but not because of human activity may answer “yes” or “no,” depending on their understanding of whether “global warming” means warming caused by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Other differences between the questions arise; for instance, respondents are much more likely to agree with survey questions that ask about more gradual change over longer time periods and mention uncertainty , as opposed to questions that ask about fast and certain change over shorter time periods. Second, researchers may want to focus their efforts on answering the questions that lead to the “Don’t know” responses. While we cannot infer how the 10–20 % of respondents in the Stanford and Michigan polls might have answered if the question was clearer, it may be that with clearer questions and answers to them, these reports would show very different “Yes” results.

7 Conclusions

This chapter discussed five longitudinal studies using various wording to ask Americans whether they believe global warming exists. After controlling for demographics, I find that question wording makes a difference, and researchers may want to focus their efforts on answering the questions that lead to the “Don’t know” responses. As scientists and engineers, we have an obligation to help those who “Don’t know” better understand climate change and the methods that can be used to mitigate emissions and adapt to the changes that may be in our future. Although it’s not very easy to take a step outside of our normal comfort zone and explore the policy implications of our work, it’s important that we do so. Yet, to truly prepare for our future, we will need to understand not only the science of climate change and engineering to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change but also the policy implications for the challenges of our time.

References

Borick C, Rabe B (2012a) The fall 2011 National survey of American public opinion on climate change. Issues Gov Stud 44:8

Borick C, Rabe B (2012b) Continued rebound in American belief in climate change: Spring 2012 NSAPOCC findings. Governance Studies at Brookings

Borick C, Rabe B (2013) The fall 2012 national surveys on energy and environment findings report for belief-related questions. The Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy, March, p. 9

Borick C, Rabe B (2014) The fall 2011 national survey of American public opinion on climate change. Issues Energ Environ Pol 7:8

CCES (2010) Cooperative congressional election study. http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/cces/home. Accessed 5 Mar 2015

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA n.d.) Carbon pollution emission guidelines for existing stationary sources: electric utility generating units. Fed Regist: Dl J United States Gov. 79 FR 67406. Proposed Rule, 13 Nov 2014

Harrison C (2013) Survey results: US views on climate adaptation. Report from Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. https://woods.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Climate_Survey_Exec_Summ_US.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Hopy D (2014) Pennsylvania voters favor EPA greenhouse gas curbs, poll shows. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 5 Jun 2014. http://www.post-gazette.com/news/politics-state/2014/06/05/Pennsylvania-voters-favor-EPA-greenhouse-gas-curbs-polls-show/stories/201406050309. Accessed 5 Mar 2015

Jordan R (2013) Americans back preparation for extreme weather and sea level rise. Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, 28 Mar 2013. https://woods.stanford.edu/news-events/news/americans-back-preparation-extreme-weather-and-sea-level-rise. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Kopicki A (2014) Is global warming real? Most Americans say yes. The New York Times, 1 Jun 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/02/upshot/is-global-warming-real-most-in-US-believe-in-climate-change.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&smid=tw-nytimes&_r=1&abt=0002&abg=1. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Krosnick J (2012) Washington Post-Stanford University survey data, June. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/documents/global-warming-poll-2.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Krosnick J, MacInnis B (2011) National survey of American public opinion on global warming: Stanford University with Ipsos and Reuters, September

Langer G (2014) Broad concern about global warming boosts support for new EPA regulations. ABC News, 2 Jun 2014

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C (2012a) Climate change in the American mind: public support for climate and energy policies in March 2012. Report from Yale project on climate change communication. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C (2012b) Climate change in the American mind: Americans’ global warming beliefs and attitudes in March 2012. Report from Yale project on climate change communication. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Feinberg G, Howe P (2012c) Extreme weather and climate change in the American mind: September 2012. Report from Yale project on climate change communication. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C (2013) Climate change in the American mind: Americans’ global warming beliefs and attitudes in April 2013. Report from Yale project on climate change communication. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Leiserowitz A, Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C (2014) Climate change in the American mind: April 2014. Report from Yale project on climate change communication. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Oreskes N (2007) The scientific consensus on climate change: how do we know we’re not wrong? In: DiMento JF, Doughman P (eds) Climate change: what it means for us, our children, and our grandchildren. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 65–71

Pew Research Center for People and the Press (2011) Modest rise in number saying there is ‘solid evidence’ of global warming: more moderate republicans see evidence of warming, 1 Dec 2011. http://www.people-press.org/2011/12/01/modest-rise-in-number-saying-there-is-solid-evidence-of-global-warming/?src=prc-headline. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Pew Research Center for People and the Press (2012) More say there is solid evidence of global warming, 15 Oct 2012. http://www.people-press.org/2012/10/15/more-say-there-is-solid-evidence-of-global-warming/2/. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Pew Research Center for People and the Press (2013) Keystone XL pipeline draws broad support: Continuing partisan divide in views of global warming, 2 Apr 2013. http://www.people-press.org/2013/04/02/keystone-xl-pipeline-draws-broad-support/. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Pew Research Center for People and the Press (2014) Climate change: key data points from Pew Research, 27 Jan 2014. http://www.people-press.org/2013/04/02/keystone-xl-pipeline-draws-broad-support/. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Ramos JL (2014) Education does not explain views on climate change well, and is not why the two parties disagree, 24 Jul 2014. http://www.insidesources.com/education-does-not-explain-views-on-climate-change-well-and-is-not-why-the-two-parties-disagree/. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Resources for the Future (2014) Surveying American attitudes toward climate change. http://www.rff.org/RFF/Documents/RFF-Resources-186_Infographic.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Saad L (2012) In US, global warming views steady despite warm winter. Gallup Politics, 30 Mar 2012. http://www.gallup.com/poll/153608/global-warming-views-steady-despite-warm-winter.aspx. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Saad L (2013) Americans’ concerns about global warming on the rise. Gallup politics, 8 Apr 2013. http://www.gallup.com/poll/161645/americans-concerns-global-warming-rise.aspx. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Saad L (2014) One in four in US are solidly skeptical of global warming. Gallup politics, 22 Apr 2014. http://www.gallup.com/poll/168620/one-four-solidly-skeptical-global-warming.aspx. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Stanford University (2013) Stanford University climate adaptation national poll conducted by GfK Custom Research North America, March. https://woods.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Climate-Adaptation-Results-TOPLINE.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb 2015

Taylor J (2013) Peer-reviewed survey finds majority of scientists skeptical of global warming crisis. Forbes, 13 Feb 2013. http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamestaylor/2013/02/13/peer-reviewed-survey-finds-majority-of-scientists-skeptical-of-global-warming-crisis/. Accessed 5 Mar 2015

Acknowledgments

I thank the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center and the Center for Climate and Energy Decision Making (created through a cooperative agreement between the NSF (SES-0345798) and Carnegie Mellon) for funding this work. Also, thanks for the significant support and input from the Center for Clean Air Policy (2012), the American Geophysical Union (2013), and the Scott Institute for Energy Innovation (2014) for publishing blogs leading up to the development of this work. Finally, I thank one anonymous reviewer who provided additional insights and wording to improve the chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Klima, K. (2016). Public Perceptions of Global Warming: Understanding Survey Differences. In: Drake, J., Kontar, Y., Eichelberger, J., Rupp, T., Taylor, K. (eds) Communicating Climate-Change and Natural Hazard Risk and Cultivating Resilience. Advances in Natural and Technological Hazards Research, vol 45. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20161-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20161-0_4

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20160-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20161-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)