Abstract

To address numerous problems with costly, unsafe, and inefficient fragmented care in the US health-care system, primary care reform has become a major area of interest. Proposed reforms have been centered around goals first articulated in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001), namely reducing medical errors, controlling cost, increasing patient-centered care, improving access, increasing the use of evidence-based care, including preventative services, and overall improving both the quality and the efficiency of the health-care delivery. A new model that is fair to say has gained the most attention by professional organizations, and many health-care stakeholders are the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

What is a Patient-Centered Medical Home?

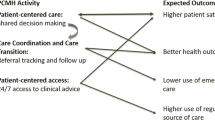

To address numerous problems with costly, unsafe, and inefficient fragmented care in the US health-care system, primary care reform has become a major area of interest. Proposed reforms have been centered around goals first articulated in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001), namely reducing medical errors, controlling cost, increasing patient-centered care, improving access, increasing the use of evidence-based care, including preventative services, and overall improving both the quality and the efficiency of the health-care delivery. A new model that is fair to say has gained the most attention by professional organizations, and many health-care stakeholders are the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) (Rittenhouse and Shortell 2009). The PCMH is defined by five core functions (AHRQ 2014):

-

1.

Comprehensive care

-

2.

Patient-centered care

-

3.

Coordinated care

-

4.

Accessible services

-

5.

Quality and safety

While not new, the term “medical home” was first used in 1967 to describe a system of care to meet the needs of children with special health-care needs. In 1992, this system of care was recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics to be expanded into general care of children, including an emphasis on accessibility, comprehensiveness, coordination, and compassion (Kilo and Wasson 2010). From there, the concept of medical homes had been discussed for general use in the primary care setting, but it was not until 2007 the term “PCMH” was agreed upon by multiple professional agencies. This new model came at an ideal time, given that rising health-care costs became a center of policy reform, and primary care was seen as playing a vital role in reducing those costs (Kilo and Wasson 2010). The five functions have been defined by federal agencies like the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Below is a description of how each of these functions is described, and what their role in promoting quality primary care is.

Comprehensive Care

The primary care setting is the ideal location for patients to have the majority of their physical and behavioral health concerns addressed. To be able to provide the comprehensive care that patients need, the PCMH focuses on providing care in a team-based approach. These teams may consist of medical providers (e.g., medical doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants), pharmacists, behavioral health providers (e.g., psychologists, social workers, and licensed clinical providers), and various other health-care providers that may provide enhanced preventative, acute, or chronic care for patients. These teams may be designed to be provided entirely within a clinic or may be built virtually by linking various providers in a community (AHRQ 2014).

While a comprehensive care team may sound ideal, it is still uncertain what professionals are needed to ensure that the comprehensive needs of patients are met. While various professions (e.g., behavioral health, nursing, and pharmacy) have written about their role in the primary care setting, there have been little data discussing how these teams should be formed, and what their goals are. For example, until recently, behavioral health professions were not consistently recommended as an integral part of the comprehensive care team.

Another issue faced with this new approach is who will pay for multiple providers seeing a patient on the same day. These team approaches may initially be more expensive than standard care, with the hope that they will produce healthier patients and offset future costs. While many have written on payment reform (Rosenthal 2008), there are still no consistent systems of payments, as these vary state by state.

Patient Centered

There has been a shift in the medical community to focus on a relationship-based orientation to health-care delivery. This new focus places the patient and their families as core members of the care team and moves to actively involve them in their treatment planning. It is within the role of health-care providers to support patients and provide them with skills to manage their own care at the level of their choosing (AHRQ 2014).

Patients are supported to better self manage and to take more responsibility for their health. To augment patient-centered care, the AHRQ offers four recommendations to help providers: (1) communicate with patients about the new model of care and what the patient’s new role is in the model, (2) promote self-care by helping patients reduce risk factors and help patients with chronic illness create and achieve self-care goals, (3) partner with patients about decision-making by helping reviewing treatment options and aid them in understanding the likely outcomes, (4) improve patient safety, by allowing them access to their records (Peikes, Genevro, Scholle and Torda 2011) .

Coordinated Care

Beyond being the setting for which patients receive the majority of their care, the PCMH is also responsible for coordinating care across the broader health-care system. These coordinated services are intended to be delivered in a “stepped-care” manner to match the needs of the patient. For example, a patient being discharged from an emergency room for a suicide attempt may require in-person consultation involving primary care and behavioral health specialists . Other consultations may achieve their goal of enhancing patient’s needs with providers or support staff interacting over the phone (Croghan and Brown 2010). It is hypothesized that this coordination is particularly important when patients need to access specialty care or are being discharged from the hospital. By doing this, the PCMH acts as the hub between patients, primary, and specialty care to ensure that needs are met and health-care plans are followed (AHRQ 2014).

Accessible Services

In order to ensure that patients have access to more affordable primary care and rely less on emergency services when urgent needs arise, it is the goal of PCMHs to create short wait times. To accomplish this, PCMHs normally offer enhanced in-person hours (e.g., working past normal business hours), provide around-the-clock telephone access to health-care providers, and use alternative methods of communication such as e-mail (AHRQ 2014).

While it is not explicated how exactly this enhanced accessibility to services should be executed, the National Committee on Quality Assurance’s (NCQA) recognition process (described below) offers very clear factors for how agencies are graded. For example, enhanced hours may include being open at 7 a.m. or closing at 8 p.m. or being open on at least two Saturdays during the month.

Quality and Safety

The use of evidence-based practices as well as clinical decision-support tools to guide treatment is a major component of the PCMH. Technologies like electronic health records (EHRs) are to be implemented to help guide decision-making and reduce the potential for error. In order to produce consistent increases in quality of care, it is also recommended that providers engage in performance measurement (e.g., number of patients within a normal blood pressure or blood sugar range). Through the use of this continued commitment to quality improvement (QI), PCMH will be able to provide more effective and safer care to their patients (AHRQ 2014).

It is hypothesized that all five of these functions must be met for primary care to fulfill its role in reducing overall health-care costs and improving the quality of care patients receive (AHRQ 2014). Therefore, creating a PCMH requires a radical shift from traditional primary care settings. This shift has given rise to national recognition processes to ensure that these services are adequately delivered. The following section describes one of these recognition models, designed to ensure the quality and integrity of a PCMH.

Recognition Process of Patient-Centered Medical Homes

Given the amount of new services required for a medical setting to deliver care consistent with the PCMH model, agencies have create national recognition standards . This process is designed to ensure that settings that use the PCMH label actually provide the enhanced services a PCMH is intended to offer. The largest recognition program in the USA, which about 10 % of all primary care clinicians operate under, is through the NCQA (2014). This section provides information on what services the NCQA requires from medical settings to achieve various levels of PCMH recognition status.

History of the Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition Process

As more data have become available on the utility and practices of PCMH and health-care policies change, the NCQA’s PCMH recognition has adapted to ensure that these new sources of information are integrated into practice. As such, the NCQA’s PCHM standards have been through four revisions, with the latest in 2014.

The precursor to the PCMH was launched in 2003, under the name of Physician Practice Connections (PPC). The PPC model emphasized the use of information technologies (IT) and systematic change to reduce the amount of medical errors that occurred from standard practices, increase the use of evidence-based care, and ensure follow-up with patients and other medical providers (NCAQ 2014).

In 2007, the joint PCMH principles were released, and in 2008, the NCQA followed with its first standards of a PCMH, which included an emphasis on the ongoing personal relationship with physicians, a team-based approach to care, care coordination, and a focus on quality and safety. There have been two updates since the 2008 release of PCMH standards, one in 2011 and the latest in 2014. Each update has “raised the bar” in order to ensure that patients receive the highest quality of care. For example, the 2014 updates have included more emphasis on integration of behavioral health care and overall team-based approaches, focused case management for high-needs populations, and more QI initiatives (NCQA 2014). The following information reflects the NCQA’s 2014 Standards and Guidelines for medication settings applying for PCMH recognition.

Who is Eligible for Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition

As denoted by the NCQA, the PCMH recognition program is a practice-based evaluation for clinicians, who may be doctors of medicine, doctors of osteopathy, advanced practice registered nurses, or physician assistants who focus on primary care specialties. Those who do not offer primary care services are not eligible for PCMH recognition. Single practices and multisite systems (i.e., systems that involve three or more sites) are eligible for the PCMH recognition (NCQA 2014).

The National Committee on Quality Assurance’s Standards of a Patient-Centered Medical Home

As of 2014, there are six PCMH program standards that are provided by the NCQA. Each of these standards was created in order to target key aspects of primary care . These general standards are broken down by elements that include specific details about performance expectations. Each element is further broken down into factors, which are specific services that the element is measured by. There are some key factors, referred to as “critical factors,” that are required for settings to receive more than minimal, or any point, for the specific element. Table 1.1 lists all of the NCQA standards, their elements, and how many points each standard is worth.

Must-Pass Elements

Beyond the six standards, the NCQA lists six must-pass elements that are considered essential components of the PCMH. To achieve PCMH recognition on any level requires a minimum score of 50 % on all of these six elements. Table 1.2 lists all six of the must-pass elements as well as the critical factor and required number to pass.

Levels of Accreditation

The NCQA recognizes three levels of PCMH status . Each level indicates the degree to which a medical setting provides the services indicated by the standards. As mentioned earlier, points are awarded to settings based on the number of factors that a medical setting is able to provide for each element listed. The determination of a setting’s level is based on the points earned by a medical setting. As mentioned earlier, regardless of the PCMH level, NCQA recognition requires that all settings meet the six must-pass elements in order to achieve any status. Table 1.3 provides the number of points necessary to achieve a certain PCMH level.

Outcome Data of Patient-Centered Medical Home

Given the intend goals of PCMH, multiple studies have focused on outcomes such as quality of care delivered, cost of care, patients experience of care , and the experience of professionals working in multidisciplinary teams. This section provides a brief overview of the results of these studies.

Quality of Care

An extensive literature conducted by Zutshi et al. (2014) investigating improvements to quality of care considered three distinct factors: processes of care , health outcomes, and mortality. They concluded of three rigorous evaluations of PCMH processes (i.e., studies that used randomly controlled trials and large health-care settings), only one study showed increased rates of medication use throughout a 2-year study, and increase use of psychotherapy or specialty mental health care during the first year but not the second. The other studies either did not show statistically significant changes in processes of care (e.g., increased rates of medication use, use of psychotherapy, and decreased hospitalizations) or statistical significance did not account for the clustered nature of the data making the results unclear. However, another study that evaluated PCMHs and process of care, the National Demonstration Project (NDP), concluded that after 26 months, the PCMH model helped improve the delivery of preventive services and chronic disease care (Jaen et al. 2010).

In regard to health-care outcomes, two studies showed improvements in some or all of the health measures. For example, the one study indicated reduced depression symptoms , improved overall quality of life, reduced overall functional impairment, and improvement in general health status over the 2-year course of the study (Zutshi et al. 2014). The other study indicated mixed results, with statically significant improvements on four of the eight Short Form (SF)-36 scales. Nonsignificant results in this study included improvements to activities of daily living and days in bed.

While these results are promising, another study investigating the impact of PCMH models on health outcomes did not produce any favorable results. For example, the data on seven of the eight scales on the SF-36 indicated no statistically significant change. The data on the final scale on the SF-36 indicated a statically significant deterioration. Therefore, the data are mixed on the impact of PCMH on health outcomes.

Finally, PCMH service effects on mortality did not produce statistically significant results. However, it is unclear whether or not this result is a function of PCMH services not changing care, or there was not enough time for mortality rates to be effected (Zutshi et al. 2014).

Cost

Reducing overall health-care costs by shifting care from specialized and emergency care and moving it into the primary care setting is one of the main hypothesized goals of the PCMH. However, current studies that examine the overall cost, hospital use, and emergency department use when PCMH systems are employed have produced mixed results.

In regard to overall costs, multiple studies produced an increase in cost by employing PCMH practices. For example, one study indicated an increase in cost of care by 12 % after the first year. Another study indicated an increase in cost of 28 % among all patients and 46 % among low-risk patients after the first year. The data from this study indicated that cost savings of 23 % were realized for high-risk patients during the third year, which was able to offset the still present 19 % increased cost of care for low-risk patients. Other studies reported no statistical difference in costs (Zutshi et al. 2014).

Hospital use across multiple studies indicates some positive results in the reduction of hospital stays and readmissions. One study indicated reduced hospitalization by 18 % and reduced readmissions by 36 % across all patients. Another study indicated a reduction in hospitalizations for high-risk subgroups for the second (44 %) and third (40 %) year of their study. Another study indicated a 22 % reduction of readmissions during the first 6 months, but these results were no longer significant after the next 6 months were included (Zutshi et al. 2014).

Emergency department also use produced mixed results. One study indicated a 24 % reduction among all patients included in the study and a 35 % reduction among high-risk patients in the second year of the PCMH system being used. Other studies did not produce statistically significant result in regard to use of emergency department use (Zutshi et al. 2014).

Experience of Care

Patient centeredness is a defining characteristic of the PCMH. It is the goal of PCMHs to have patients and their families help create individualized treatment plans and be one of the primary drivers in their health-care experience. Therefore, measuring whether or not PCMHs influence the experience of care is an important metric.

In regard to patient experience, multiple studies show improvements in various aspects of care. For example, one study showed improved satisfaction with depression care after 3 months and again at 12 months. Another study indicated improvements in veterans’ access to care, interpersonal experience, technical quality, communication. However, satisfaction with care was not significantly different (Zutshi et al. 2014). This result of not changing patient satisfaction over multiple domains (i.e., empowerment, general health status, and satisfaction with service relationship) was also replicated in the NDP that evaluated 36 practices over 26 months (Jaen et al. 2010).

Family and caregiver experience also produced mostly positive or uncertain results. One study indicated improved ratings of quality of care received by loved ones. Beyond satisfaction, one of the two measures assessing caregiver burden also showed statistically significant reduction (Zutshi et al. 2014).

Professional Experience

Professional experience is also hypothesized to change with the use of the PCMH model. By using new systems, like enhanced collaborative care teams, providers may focus on areas that they specialize in, and by improving quality of care for patients, increase their own personal work satisfaction.

In the one study described by Zutshi et al. (2014), there were no statistically significant difference between intervention and control groups in regard to satisfaction with care management , time spent on chronic care, knowledge of patients’ personal circumstances, and coordination of care. There were also uncertain statistical results in regard to communication and knowledge.

However, professional experience in new PCMH was an area of concern and caution (Nutting et al. 2009). Change fatigue from the high-paced and new demands to meet the new model of care can be result in staff burnout and high rates of turnover if not properly monitored, and changes in practices are made to fast (Nutting et al. 2009). It is also recommended that physicians be assisted with the professional transformation needed to effectively operate with practices like working with practice teams and patient partnering (Nutting et al. 2009).

All of the preliminary results for PCMH within the literature review conducted by Zutshi et al. (2014) show mixed results across the various aspects that the new system is hypothesized to improve. It is important to note that there are smaller studies or studies that do not use rigorous methods of testing that indicate positive results for some of these factors. However, many authors have indicated that it is still too soon to come to any strong conclusions of whether or not PCMH work as intended, and that the model still holds much promise for addressing many of the health-care issues currently being faced in the USA.

The Role of Behavioral Health Providers

The role of a behavioral health provider in a PCMH is unclear . There are many conceptualizations of a PCMH that do have a behavioral health provider as a member of the core team. There are no studies showing the differential outcomes when a behavioral health provider is included versus omitted. Certainly, these studies need to be conducted. However, one study concluded that the delays in external referrals for psychiatric and psychological care adversely affected outcomes of a PCMH.

There are many technical questions that need to be answered related to the inclusion of a behavioral health provider in a PCMH including:

-

1.

What kind or kinds of behavioral health providers—psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, marriage, family therapists, etc.?

-

2.

What kind or kinds of behavioral health providers—psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, marriage, family therapists, etc.?

-

3.

What exactly are the skill sets/core competencies of these behavioral health providers? Do they need specialized skill sets in order to function optimally in a PCMH, for example, in working in a team, in brief interventions and assessments , in medical psychology?

-

4.

What full-time equivalency ratios are needed, for example, one full-time behavioral health provider for every x primary care medical provider?

-

5.

Are there sufficient behavioral health providers currently available, or is there a workforce shortage of these (see O’Donohue and Maragakis 2014 for an argument that there is a significant workforce shortage)? If there is such a national workforce shortage, what can be done about this?

-

6.

What are the optimal clinical processes for a behavioral health provider in a PCMH? What kinds of patients or problems should be prioritized? When do they treat internally versus refer? What behavioral health screens, if any, ought to be used? What are the evidence-based assessment and treatment protocols for the wide variety of clinical problems addressed? What behavioral health outcome variables ought to be measured? What is the optimal balance between preventative services versus clinical services? What is the optimal balance between treating typical mental disorders such as depression versus treating medical problems such as chronic pain or treatment nonadherence? What patients need more intensive team-based treatment?

-

7.

How is the inclusion of a behavioral health provider in a PCMH to be financed? How is their billing to work? How can their role in contributing to final overall costs be parsed?

-

8.

How are operational processes and work flows to be defined? Is the EHR optimal? Are there special procedures for dealing with sensitive behavioral health information? What is the role of the behavioral health provider in producing improved patient-centered care?

-

9.

Finally, how do different conceptualizations of all these parameters contribute to the desired outcomes of a PCHM?

Conclusions

The PCMH should be viewed as a hypothesis not a conclusion. Epistemically, the positive outcomes of PCMHs are not well-supported facts: There are too few data showing that PCMHs achieves its aims regarding cost, effectiveness, patient centeredness, access, and safety, and it is fair to say that currently some data that show they do not. However, it is clear that health-care delivery needs reform and the aspirations of the PCMH appear sound.

One common mistake in health care is to treat an attractive notion as a well-corroborated fact. It might be argued that this is even happening with PCMHs. It has become a strong movement: It at times is even viewed as a necessity. However, the data—or in other words—measured experience—do not currently justify such a strong commitment—too much is currently unknown. It is recommended that all proceed with some caution. Reforms can fail or disappoint.

We suggest that it is critical that a meta-position of science and QI be taken, and this meta-position is currently more important than any of the specifics of a PCMH. The view needs to be: We need to study the causal processes needed to actually instantiate the desired goals of the PCMH, and more specifically, we need to understand the role of a behavioral health provider (variously conceived) in producing these or failing to produce these. We conjecture that there are numerous technological problems that need to be solved in order for these aims to be instantiated, and it would be a mistake for these not to be explicated and treated as challenges to be solved.

We suggest that funding sources orient to these technological problems and explicitly call for proposals to study solutions. We suggest that journals produce special issues and prioritize papers that attempt to solve these. We also suggest that these be considered when students are looking for dissertation topics. A slight rephrasing of Gordon Paul’s ultimate clinical question is relevant here: “What treatment, by whom, is most effective for this individual, with that specific problem, under which set of circumstances, and how does it come about?” (Paul 1969, p. 44). We might modify this: What outcomes (e.g., cost reductions), by what team, are most effective for this individual patient, with what problems, under which set of circumstances, and how does it come about? This question is properly nuanced but requires a lot of programmatic data collection to yield data to answer it.

Thus, we think that “research projects” are important but will be insufficient to provide the data necessary to answer this question. We conclude therefore that all PCMHs be conducted in the context of systematic QI programs (see Maragakis and O’Donohue 2014 in press for more information on QI and behavioral health) . Because so little is currently known, the QI approach is ideal: Conjectures are tested in actual practice, and then reforms are hypothesized, and the testing cycle begins again. There are so many parameters that need evaluation that this is the only orientation that may be sufficient to produce the needed data. We believe that doctorate-level behavioral health providers have the capacity to help the team design and implement QI programs—however, it is also fair to say that typically, the doctorate-level training has too little emphasis on QI and too much on research designs that are less practical. Part of the agenda is to improve the competency of all team members to work within a QI system.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2014). Defining the PCMH. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed 11 oct 2014.

Croghan, T. W., Brown, J. D. (2010). Integrating Mental Health Treatment Into the Patient Centered Medical Home. (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200900019I TO2.) AHRQ Publication No. 10-0084-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Jaen, C. R., Ferrer, R. l., Miller, W. L., Palmer, R. F., Wood, R., Davila, M., Stewart, E. E., Crabtree, B. F., Nutting, P. A., & Stange, K. C. (2010). Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Annals of Family Medicine, 8(1), S57–S67.

Kilo, C., & Wasson, J. (2010). Practice redesign and the patient-centered medical home: History, promises, and challenges. Health Affairs, 29(5), 773–778.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. (2014). Standards and guidelines for NCQA’s patient-centered medical home (PCMH) 2014. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Nutting, P. A., Miller, W. L., Crabtree, B. F., Jaen, C. R., Stewart, E. E., & Stange, K. C. (2009). Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Annals of Family Medicine, 7(3), 254–260.

O’Donohue, W., & Maragakis, A. (2014). Healthcare reform means training reform. Journal of Online Doctoral Education, 1(1), 73–88.

Paul, G. L. (1969). Behavior modification research: Design and tactics. In C. M. Franks (Ed.) Behavior therapy: Appraisal and status (pp. 29-62). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Peikes, D., Genevro, J., Scholle, SH., & Torda, P. (2011). The patient-centered medical home: Strategies to put patients at the center of primary care. AHRQ Publication No. 11–0029. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Rittenhouse, D., & Shortell, S. (2009). The patient-centered medical home: will its stand the test of time? Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(19), 2038–2040.

Rosenthal, T. (2008). The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. Family Medicine and the Health Care System, 21(5), 427–440.

Zutshi, A., Peikes, D., Smith, K., Genevro, J., Azur, M., Parchman, M., & Meyers, D. (2014) The medical home: What do we know, what do we need to know? A review of the earliest evidence on the effectivness of the patient-centered medical home model. AHRQ Publication No. 12(14)-0020-1-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Maragakis, A., O’Donohue, W. (2015). Patient-Centered Medical Homes: The Promise and the Research Agenda. In: O'Donohue, W., Maragakis, A. (eds) Integrated Primary and Behavioral Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19036-5_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19036-5_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-19035-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-19036-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)