Abstract

Perfectionism and eating disorders have long been associated with each other in theoretical perspectives, but only recently has evidence emerged that informs us of the nature of the relationship between the two. The prominent theories that link perfectionism and eating disorders are reviewed, including the other types of traits that may increase the influence of perfectionism on the development of eating disorders. Cross-sectional associations are summarised, showing an association of two types of perfectionism with eating disorders: wanting to achieve high personal standards (PS) and the degree of concern and self-criticism generated when it is perceived that standards are not met. The body of research examining causal relationships between perfectionism and eating disorders (longitudinal, studies of people recovered from eating disorders, experimental and prevention and treatment studies) is also reviewed, supporting the role of perfectionism in increasing development of disordered eating. However, the mechanisms of action are likely to be complex. We need to develop a better understanding of how perfectionism may increase risk for the development of an eating disorder, and of the comparative importance of modifying perfectionism in both prevention and treatment of eating disorders compared to other risk and maintenance factors.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Overview

The coupling of perfectionism and eating disorders has a very long history, with a case study emerging from the medieval years. St. Catherine of Siena (1347–1380) is thought to have suffered from anorexia nervosa . From the age of 16 years, she ate less and less until eventually she ate nothing but the daily Eucharist, maintaining this regime even in the face of disapproval from the clergy. She died in Rome at the age of 33, a death considered to be caused by the effects related to starvation. One of her writings gives us a clue to some of the issues that may have maintained this sustained and committed behaviour:

Make a supreme effort to root out self-love from your heart and to plant in its place this holy self-hatred. This is the royal road by which we turn our backs on mediocrity, and which leads us without fail to the summit of perfection.

A more modern example of the co-occurrence of perfectionism and eating disorders comes from Jenni Schaefer, the author of “Goodbye Ed, Hello me; Recover from your eating disorder and fall in love with life”:

In the past, my brain could only compute perfection or failure—nothing in between. So words like competent, acceptable, satisfactory, and good enough fell into the failure category.

The purpose of this chapter is to examine the nature of the relationship between perfectionism and eating disorders, in terms of how this relationship is described in different theories, the evidence with respect to the direction of this relationship and the usefulness of interventions which seek to decrease perfectionism in terms of their impact on disordered eating. Disordered eating and eating disorders cover a variety of different behaviours and attitudes, but the core features that are discussed in the current chapter include the following:

-

The importance of control overeating, weight and shape in terms of determining self-worth;

-

Objective binge eating, defined as eating a large amount of food in a circumscribed period of time (2 h) while experiencing a feeling of lack of control;

-

Purging behaviours, which can include the use of self-induced vomiting, diuretics or laxatives for the purpose of controlling weight and shape;

-

Extreme forms of non-purging behaviours such as driven exercise and fasting used primarily for the purpose of controlling weight and shape.

Theoretical Perspectives on Perfectionism and Eating Disorders

Hilde Bruch (1974), a pioneer in the field of eating disorders , noted that clients with eating disorders demonstrate “superperfection” and argued that the adolescent turns to body weight as a concrete source of self-definition and as a means of compensating for the lack of a clear identity as well as for associated feelings of powerlessness and incompetence. In 1978, Peter Slade developed a functional analytical model of anorexia nervosa in which he also hypothesised that, in the context of adolescent conflicts, interpersonal problems, and stress and failure experiences, the adolescent with low self-esteem and perfectionistic tendencies would feel a need to control completely, or attain success, in some aspect of life. One of the aspects of life most salient to young women is in the domain of body weight and size. He described this perfectionistic viewpoint in a very similar manner to that of Schaefer:

[adolescents] see events and their own achievements in black and white terms, such that anything else less than idealized, perfect success or attainment represents failure and lack of success (p. 171).

Since this early theoretical emphasis on the role of perfectionism in increasing risk for eating disorders, a number of authors have attempted to develop testable theories that define how perfectionism may work together with other risk factors to cause and maintain eating disorders. We look at each of the most prominent theories in turn .

The Three-Factor Model

First proposed by Vohs and colleagues in 1999, this model posited that self-esteem moderates the relationship between the interaction of perfectionism and perceived weight status (regardless of actual weight status), and changes in bulimic symptoms. In other words, perfectionists who perceived themselves as being overweight would exhibit higher levels of bulimic symptomology if their self-esteem was low, compared to perfectionists with weight concerns who have high self-esteem. Low self-esteem was seen to interfere with the attainment of desired goals, which in the context of frustration with respect to any weight-related goals (e.g. wanting to lose weight) can trigger negative mood in perfectionists and result in disordered eating. This model, after accounting for the effects of body mass index (BMI), was supported across a number of early studies (Vohs, Voelz et al., 2001; Vohs, Bardone, Joiner, Abramson, & Heatherton, 1999; Vohs, Heatherton, & Herrin, 2001).

Since being developed, the three-factor model has been revised in a number of ways. First, perceived weight status has been operationalised as body dissatisfaction (Vohs, Voelz et al., 2001) and more recently as weight and shape concern (Bardone-Cone et al., 2008) using the relevant subscales of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). Second, recent studies have replaced the Bulimia subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI; Clausen, Rosenvinge, Friborg, & Rokkedal, 2011) as the measure of bulimic behaviours with the number of episodes of binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviour as assessed by the EDE-Q (Bardone-Cone, Abramson, Vohs, Heatherton, & Joiner, 2006; Bardone-Cone et al., 2008). Third, given that independent attempts to replicate the model using self-esteem have persistently failed (Shaw, Stice, & Springer, 2004; Steele, Corsini, & Wade, 2007; Tissot & Crowther, 2008; Watson, Steele, Bergin, Fursland, & Wade, 2011), the three-factor model has replaced self-esteem with self-efficacy (Bardone-Cone et al., 2006; 2008). Self-efficacy was considered not as an alternative to self-esteem but rather as a more relevant component of the original construct of interest, namely doubt about one’s ability to achieve and perceiving interference with goal attainment.

The inclusion of self-efficacy may show better replicability, with one study indicating it prospectively predicted bingeing but not purging behaviours (Bardone-Cone et al., 2006) where perfectionism was measured using the subscale from the EDI that includes a mix of items related to “socially prescribed” and “self-oriented” perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Bardone-Cone et al. (2008) found that a three-way interaction with both personal standards (PS) and concern over mistakes perfectionism from the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990) predicted increases in binge eating. That is, young women who reported self-critical reactions to a failure to attain goals and who were low in self-efficacy and had concerns about shape and weight experienced the most binge eating episodes, as shown in Fig. 9.1. The use of PS perfectionism in the interaction was also associated with more episodes of self-induced vomiting. In other words, young women who reported the importance of goal attainment and excellence and who were low in self-efficacy and had concerns about shape and weight experienced the most purging behaviour. To date, no treatments have been formulated based on this model.

The Transdiagnostic Theory of Eating Disorders

The transdiagnostic theory of eating disorders is cognitive behavioural in nature and grew primarily from the cognitive behavioural theory of bulimia nervosa (Fairburn, 1997). A key aspect of the rationale for developing the theory was that cognitive behaviour therapy for bulimia nervosa was effective but that half of the patients were failing to make a full and lasting recovery (Fairburn, Shafran, & Cooper, 2003). One potential explanation was the narrow focus on specific psychopathology of eating, shape, weight and their control. The theory was therefore extended to incorporate four additional maintaining mechanisms derived from the literature—clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem, mood intolerance and interpersonal difficulties (see Fig. 9.2).

Like the core psychopathology of eating disorders, “clinical perfectionism” was considered as a dysfunctional scheme for self-evaluation. It was defined as the overevaluation of striving for, and achievement of, personally demanding standards despite adverse consequences (Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn, 2002). The application of these standards for eating, shape, weight and their control was suggested to interact with the eating disorder psychopathology and maintain it. In this account, the fears of “fatness”, weight gain and overeating are considered as exemplars of the characteristic fear of failure of clinical perfectionism; shape and weight checking is viewed as counterproductive behavioural strategy and the characteristic self-criticism in patients with eating disorders viewed as arising from negatively biased appraisals of performance. The self-criticism was hypothesised to maintain negative self-evaluation which, in turn, was suggested to encourage even more determined striving to meet valued goals related to eating, shape and weight—thereby serving to maintain the eating disorder. It was therefore predicted that reducing clinical perfectionism would remove an additional maintaining mechanism for some patients who held this belief system and would improve the eating disorder .

It should be noted that in the original paper describing the transdiagnostic theory of eating disorders, the argument was made that eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified) were maintained by shared, but distinctive, psychopathological processes with patients frequently migrating across diagnostic categories. It was therefore concluded that common mechanisms, including clinical perfectionism, are involved in the persistence of bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa and the atypical eating disorders.

The implication of the transdiagnostic theory of eating disorders for treatment is that clinicians should consider identifying and potentially addressing clinical perfectionism in the context of eating disorders when it appears to be a barrier to change. Data evaluating the transdiagnostic treatment indicate that patients with marked mood intolerance, clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem or interpersonal difficulties respond better to the treatment that incorporates techniques to address their specific difficulty (Fairburn et al., 2009). The treatment overall has promising results (Fairburn et al., 2009; Byrne, Fursland, Allen, & Watson, 2011; Dalle Grave et al., 2013; Dalle Grave, Calugi, Doll, Fairburn, 2013; Fairburn et al., 2015).

The Cognitive-Interpersonal Model of Anorexia Nervosa

This model has been formulated specifically to help inform development of treatment for anorexia nervosa (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006), in line with principles encapsulated in the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for the development of complex interventions (Craig et al., 2008). While no formal test of the model has been conducted, the development has involved an iterative translational process between basic research and model/treatment development, combining a top-down (i.e. theory-led, data-driven, quantitative) and bottom-up (i.e. patient and clinician experience-led, qualitative) approach (Schmidt, Wade, & Treasure, 2014), resulting in one revision of the model to date (Treasure & Schmidt, 2013) .

The model proposes that anorexia nervosa typically arises in people who have anxious and perfectionist traits and is maintained by four broad factors (Schmidt et al., 2014) as shown in Fig. 9.3. The factors include: a rigid, detail-focused and perfectionist information processing style; impairments in the socio-emotional domain (such as avoidance of the experience and expression of emotions in the context of close relationships); the development of beliefs about the utility of anorexia nervosa; and inadvertent actions of close others that may serve to maintain the anorexia nervosa, e.g. high levels of expressed emotion, accommodation and enabling behaviours. Starvation intensifies these problems, thereby forming a recursive loop between the consequences of starvation and these maintenance factors.

In terms of the specific relationship between perfectionism and eating, Schmidt and Treasure (2006) suggest the following:

Individuals with these traits value perfection and fear making mistakes. They are excessively conscientious and cognitively rigid … The traits (being rigidly rule-bound, striving for perfection) can facilitate persistent dietary restriction and the control of appetite. A wish for simplicity and focus on details make this type of behaviour satisfying and may lead to the … belief ‘anorexia nervosa makes me feel in control’ (p. 349).

The type of perfectionism that they refer to is similar to the “global childhood rigidity” (Anderluh, Tchanturia, Rabe-Hesketh, Collier, & Treasure, 2009), which was found by Halmi and colleagues (2012) to be the predominate perfectionistic feature preceding development across all anorexia nervosa subtypes, including restricting, purging and binge eating subtypes. It has been proposed that childhood temperament including anxiety, obsessions and perfectionism may reflect neurobiological risk factors for developing anorexia nervosa, where restricted eating is used to moderate negative mood caused by skewed interactions between serotonin inhibitory and dopamine reward systems (Kaye, Wierenga, Bailer, Simmons, & Bischoff-Grethe, 2013) .

The Maudsley Model of Treatment of Adults with anorexia nervosa (MANTRA) has been developed from this model, with a central focus on promoting more flexible thinking and less rigidity (Schmidt et al., 2014). MANTRA has been evaluated across two studies. The first of these was a small case series (Wade, Treasure, & Schmidt, 2011) where patients showed significant improvements at 12-month follow-up on eating disorder symptoms, weight and other variables with large to very large effect sizes in an intention-to-treat analysis. A larger pilot randomised controlled trial of 72 adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa compared MANTRA against Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM; McIntosh et al., 2005) and found overall significant improvements on weight, eating disorders symptoms, depression and anxiety, with no differences between these treatments (Schmidt et al., 2012). An exploratory analysis of 53 participants with more severe anorexia nervosa (BMI < 17.5) showed MANTRA patients to show further improvement in weight at 12-month follow-up, whereas those treated with SSCM did not (Schmidt et al., 2012). While further research on the efficacy of MANTRA is required, along with dismantling studies identifying the effective components, these findings may suggest the usefulness of tackling perfectionism in treating anorexia nervosa.

Evidence Supporting an Association Between Perfectionism and ED

Cross-Sectional Studies

Systematic reviews suggest that perfectionism is a risk factor for eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007; Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, & Agras, 2004; Shafran & Mansell, 2001; Stice, 2002; Egan, Wade, & Shafran, 2011). It has been suggested that both healthy perfectionism (i.e. striving for achievement) and unhealthy perfectionism (i.e. self-criticism when goals are not achieved to what is considered to be an acceptable level) are associated with disordered eating (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007).

Currently, the majority of the evidence for the relationship between perfectionism and disordered eating rests on cross-sectional studies. Correlational studies have demonstrated that individuals with bulimia nervosa have significantly higher levels of perfectionism levels than healthy controls (Lilenfeld, Wonderlich, Riso, Crosby, & Mitchell, 2004). Retrospective case-control studies have also found significantly higher rates of childhood perfectionism in individuals with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa than healthy controls (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll, & Welch, 1999; Fairburn, Welch, Doll, Davies, & O’Connor, 1997; Halmi et al., 2012). Childhood perfectionism is also recalled as being higher in individuals with anorexia nervosa compared to psychiatric controls (Pike et al., 2008; Machado, Gonçalves, Martins, Hoek, & Machado, 2014). Elevated concern over mistakes , a subscale of the FMPS that loads on the self-critical evaluative concerns (EC) construct, is associated with retrospectively reported eating disorders but not with other psychiatric disorders (Bulik et al., 2003). Females with a self-reported lifetime history of fasting or purging (i.e. self-induced vomiting or abuse of laxatives or diuretics) exhibit significantly higher levels of perfectionism than healthy controls (Forbush, Heatherton, & Keel, 2007).

Research also indicates that socially prescribed perfectionism (i.e. the need to attain standards perceived to be imposed by significant others), measured by the Hewitt and Flett Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (HMPS; Hewitt & Flett, 1991), is significantly elevated in people with eating disorders (Bastiani, Rao, Weltzin, & Kaye, 1995; Cockell et al., 2002). Previous theorists (Bruch, 1974) have emphasised that both intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of perfectionism are implicated in the emergence and continuance of eating disorder symptoms. Longitudinal research over 7 years of 13-year-old girls found that a “wish to be thinner” and mothers’ ratings on perfectionism contributed most to the prediction of disturbed eating attitudes (Westerberg-Jacobson, Edlund, & Ghaderi, 2010). A study of 433 “trios” (a female with anorexia nervosa or “proband” and her mother and father) found that the most severe disordered eating in the proband was associated with mothers who also had elevations on eating disorder symptoms and anxious/perfectionistic traits (Jacobs et al., 2009). Elevated perfectionism in people in the social circle may not indicate perfectionistic pressures in the relationship but may rather indicate a genetic susceptibility, given that around 25–39 % of the variance of perfectionism can be accounted for by genetic effects (Wade & Bulik, 2007). While perfectionism in the father has not been implicated to date, the importance of paternal variables in terms of contribution to risk for eating disorders has been found across a variety of longitudinal studies, including paternal eating attitudes (Westerberg, Edlund, & Ghaderi, 2008) and importance of weight to father (Field et al., 2008), which may indicate some perfectionistic pressures specific to appearance and weight from the fathers or shared genetic vulnerability.

It should be noted that while it has been suggested that striving to achieve high standards does not play a role in the development of psychopathology generally (Stoeber & Otto, 2006), eating disorders have previously been singled out as being unique in terms of associations with both healthy and unhealthy perfectionism (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007). As mentioned earlier, binge eating in college-aged women has been shown to increase over time in the presence of two different types of perfectionism (Bardone-Cone et al., 2008), PS and EC . One study explicitly examined different clusters of these two types of perfectionism in young adolescents (Boone, Soenens, Braet, & Goossens, 2010) and their associations with eating disorder symptoms measured with the EDE-Q. Cluster analysis identified four groups of adolescents: (i) high PS and EC, (ii) high EC only, (iii) high PS and low EC and (iv) low PS and EC. The first cluster, around 15 % of the sample, experienced the highest levels of disordered eating across all four subscales of the EDE-Q. The way in which these two types of perfectionism may work together to increase risk for disordered eating requires further examination in longitudinal designs as we need to develop a better understanding of the contexts in which high standards can be damaging and when it can be protective.

Longitudinal Studies

While some longitudinal studies have found that perfectionism is related to increases in eating disorder symptoms (e.g. Boone, Soenens, & Braet, 2010; Mackinnon et al., 2011), other studies have failed to confirm these findings (e.g. Gustafsson, Edlund, Kjellin, & Norring, 2009; Vohs, et al., 1999; Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, Keel, & Klump, 1999). Examination of simple relationships in this body of research is likely to contribute to these inconsistent findings as it has long been recognised that it is likely that more complex multivariate models will be required to properly understand the postulated effect of perfectionism on risk for disordered eating (Stice, 2002; Bardone-Cone et al., 2007). An example of these multivariate relationships is encapsulated in the three-factor model (Bardone-Cone et al., 2006; 2008) described above. In other words, perfectionism may only exert an effect on the development of disordered eating through its relationship with other important risk factors.

In addition to the three-factor model, several complex longitudinal models have been tested which show some promise. The first, in a sample of young adolescent girls (average age of 13 years) where three waves of data were collected over a 12-month period, showed body dissatisfaction moderated the effect of perfectionism on changes in importance of weight and shape (Boone, Soenens, & Luyten, 2014). Higher levels of both concern over mistakes and PS perfectionism with higher levels of body dissatisfaction at baseline significantly increased the importance of weight and shape at 12-month follow-up. Importance of weight and shape has been described as the “core psychopathology” of eating disorders (Cooper & Fairburn, 1993) and forms part of the diagnostic criteria for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. It has been found to predict the growth of diagnostic threshold level of disordered eating behaviours in adolescents over a 12-month period (Wilksch & Wade, 2010). Mediational relationships were also investigated, but there was no support for a longitudinal mediational model where body dissatisfaction at 6-month follow-up was postulated to mediate the relationship between baseline perfectionism and overevaluation of weight and shape at 12-month follow-up.

A second study with 12- to 15-year-old boys and girls over a 12-month period, with three waves of data collected at 6-month intervals, did support mediational relationships (Boone, Vansteenkiste, Soenens, der Kaap-Deeder, & Verstuyf, 2014). Need frustration, measured with the balanced measure of psychological needs (Sheldon & Hilpert, 2012), was postulated to be a mediator of the relationship between self-critical perfectionism and the growth of binge eating symptoms. Need frustration refers to the frustration of needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness, and is thought to be of relevance to self-critical perfectionism where positive feelings after achievement are short-lived and replaced with a focus on the next demanding standard, and where attainment of goals can often be dismissed. In both boys and girls, higher levels of self-critical perfectionism at the first wave of assessment had a significant association with needs frustration at the second wave, which in turn had a significant association with the growth of tendencies to think about and engage in bouts of uncontrollable overeating as measured by the bulimia subscale of the EDI.

A third study has also examined longitudinal mediation pathways for risk for developing disordered eating in young adolescents (Wade, Wilksch, Paxton, Byrne, & Austin, submitted). Growth of the importance of weight and shape over a 12-month period in girls was predicted by the initial baseline level of concern over mistakes perfectionism and its relationship with higher levels of ineffectiveness subsequent to baseline and measured on three occasions. Ineffectiveness has previously been shown to predict the growth of the importance of weight and shape (Wilksch & Wade, 2010) and can be likened to the concept of self-efficacy, in that it was measured by the EDI with items related to feelings of inadequacy, insecurity, worthlessness and having no control over one’s life. This is consistent with the most endorsed worries of women with anorexia nervosa which do not relate to the aspects of eating or weight but to issues that increase a sense of ineffectiveness such as rejection and abandonment, negative perceptions of self and experience of negative emotions (Sternheim et al., 2012). Interestingly, when baseline PS perfectionism was examined, there was no significant relationship with either levels of subsequent ineffectiveness or increases in the importance of weight and shape.

In summary, there is growing evidence of a longitudinal (i.e. causal) relationship between perfectionism and growth of either disordered eating or risk for disordered eating, in the presence of key variables, with the most promising being constructs that relate to self-efficacy and ineffectiveness. This echoes the focus formulated many years ago by Hilde Bruch (1974), where body weight becomes a means of self-definition and compensation for feelings of powerlessness and incompetence in the presence of perfectionism . The degree to which different types of perfectionism contribute to this risk requires further elucidation.

Studies of People Recovered from Eating Disorders

Several studies have investigated people who have had an eating disorder and compared the levels of perfectionism with people who have never had an eating disorder and people who still have an eating disorder in order to understand if perfectionism influences development of disordered eating. The presence of elevated perfectionism in the recovered group compared to the healthy group would suggest one of the two things: first, dispositional perfectionism increased risk for development of an eating disorder, or second, the experience of an eating disorder has had a “scar effect” leaving the person more perfectionistic than before they developed the eating disorder.

Most research consistently shows perfectionism to be elevated in people with eating disorders and people recovering from eating disorders compared to healthy controls (Bastiani et al., 1995; Srinivasagam et al., 1995; Bardone-Cone, Sturm, Lawson, Robinson, & Smith, 2010; Halmi et al., 2000; Lilenfeld et al., 2000). However, other studies have suggested that recovery, when robustly defined, is associated with perfectionism levels that are no different from healthy controls (Bardone-Cone et al., 2010). The different definitions of recovery used in eating disorder research do pose considerable difficulties for making clear conclusions about a number of issues, including prediction of recovery and the study of mechanisms involved in recovery (Williams, Watts, & Wade, 2012). Although these latter findings may indicate that perfectionism is not a risk factor for eating disorders (i.e. does not cause eating disorders), it is still consistent with the suggestion that interventions that help decrease perfectionism may be key to making full recovery attainable (Bardone-Cone et al., 2010) .

Experimental Studies

A range of novel experimental designs have been employed to investigate the cognitive, affective and behavioural processes associated with perfectionism. For example, studies manipulating reactions to success and failure by providing contrived feedback on task performance have demonstrated the negatively biased appraisals of performance characteristic of perfectionists. While there is inconsistency regarding the type of perfectionism that is most problematic, studies by Besser and colleagues (Besser, Flett, & Hewitt, 2004; Besser, Flett, Hewitt, & Guez, 2008) suggest that perfectionists fail to internalise, or have difficulty processing, positive feedback and success. In fact, experimental studies investigating resetting of PS have demonstrated that perfectionists not only discount their success, but re-evaluate their PS as insufficiently demanding and raise their goals following success (Kobori, Hayakawa, & Tanna, 2009; Stoeber, Hutchfield, & Wood, 2008).

With respect to eating disorder psychopathology, specifically, the impact of perfectionism has been investigated in two nonclinical experimental studies. Shafran, Lee, Payne and Fairburn (2006) experimentally manipulated individual PS to investigate their influence on eating attitudes and behaviour. Participants were randomly allocated to either a high PS (perfectionist) or a low PS (non-perfectionist) condition. In the high PS condition, participants agreed to pursue the highest possible standards in everything, including thoughts, words and actions, for a 24 h period. In the low PS condition, participants agreed to perform at the minimum possible standard. Post manipulation, individuals in the high PS condition exhibited greater restriction of higher calorie foods and overall food consumption, as well as greater regret after eating, than individuals in the low PS group.

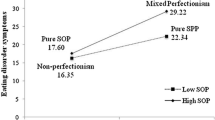

Boone, Soenens, Vansteenkiste and Braet (2012) extended this study in three ways. First, they examined the impact of trait perfectionism on the experimental manipulation of perfectionism by including a pre-manipulation measure of dispositional perfectionism. This consisted of the FMPS concern over mistakes and doubts about actions subscales to assess EC perfectionism and the FMPS personal standards subscale to assess PS perfectionism . Second, they also adopted a multidimensional approach to the manipulation of perfectionism. In addition to the two conditions manipulating high and low PS, a third condition was included to activate both PS and EC perfectionism. In this condition, participants agreed to pursue the highest possible standards to avoid failing or disappointing themselves or others. Third, this study examined the impact of the manipulation across broader range of eating disorder symptoms including items related to dietary restraint (e.g. attempted and actual restriction and restraint, reduced calories, reduced amount of food); body dissatisfaction (e.g. stomach too big, thighs not the right size, dissatisfied with shape of body); and binge eating (e.g. eating when upset, stuffed with food).

Both experimental manipulations induced increased levels of state PS and EC perfectionism compared to the non-perfectionist group, indicating that manipulating PS alone is sufficient to increase negative self-evaluation associated with EC perfectionism. In addition, both perfectionism groups experienced increases in restraint and binge eating symptomatology, but not body dissatisfaction compared to the non-perfectionist group. However, mediation analysis confirmed the causal role of state EC perfectionism only in eating disorder symptoms. While PS perfectionism was related to restraint, this correlation was not supported after controlling for the influence of EC perfectionism. EC perfectionism on the other hand was correlated with restraint, body dissatisfaction and binge eating. Further, state EC perfectionism was supported as a full mediator of the effect of the perfectionism manipulation on both restraint and binge eating. These findings were supported irrespective of trait perfectionism levels.

Based on this combined research, perfectionism is indicated as a causal risk factor for eating disorder psychopathology. Further, it suggests that perfectionism itself is malleable and may be sensitive not only to situational circumstances but also to interventions, and is therefore also a potential target for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders.

Prevention and Treatment Studies

Research unambiguously indicates that perfectionism is not only treatable but that targeted cognitive behavioural interventions can significantly improve psychopathology. A recent meta-analysis (Lloyd, Schmidt, Khondoker, & Tchanturia, 2014) evaluated eight treatment studies employing cognitive behavioural techniques targeting perfectionism in individual therapy, guided self-help, web-based intervention or group therapy. Large pooled effect sizes were observed for improvements in perfectionism itself, and medium pooled effect sizes were observed for improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression. To date, three studies have investigated the impact of treatment targeting perfectionism in clinical samples with eating disorders across a range of delivery formats.

Two of these studies have investigated the impact of group-based cognitive behaviour treatment for perfectionism within existing treatment programs. Lloyd, Fleming, Schmidt and Tchanturia (2014) evaluated a six-session treatment with women in an inpatient program for anorexia nervosa . Findings supported the efficacy of this form of treatment for improving perfectionism (with medium effect sizes). However, potential impacts on aspects of eating disorder psychopathology in comparison with treatment as usual were not reported. A study conducted by Goldstein and colleagues (2014) has evaluated the outcomes of group-based perfectionism therapy on both perfectionism and psychopathology. In this trial, seven sessions were delivered to a transdiagnostic eating disorder sample of patients with anorexia nervosa , bulimia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified, within a day program treatment setting. Participants were randomly allocated to receive treatment as usual including a general cognitive-behavioural-based group, or treatment as usual with cognitive behavioural treatment for perfectionism. Both groups produced improvements in perfectionism and eating disorder psychopathology, with no differences between the groups. It is acknowledged by the authors that both cognitive behavioural groups in this study may have challenged aspects of perfectionism, and that ceiling effects associated with adding a small active component to an already successful treatment program (7 hours out of 136 overall treatment hours) may have masked a potential small effect.

Using a six-session guided self-help treatment program, Steele and Wade (2008) evaluated the impact of targeting perfectionism to reduce bulimic symptoms. Participants included women with either bulimia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified with bingeing and purging. The study compared the effects of three guided self-help treatments: a cognitive behavioural perfectionism intervention with no eating disorder specific components; a traditional cognitive behavioural eating disorder intervention; and a placebo intervention including mindfulness techniques. Although there were no significant differences between the groups, effect sizes indicated a mixed picture. Effect sizes were larger for guided self-help targeting perfectionism than other conditions in improving excessive exercise, self-esteem and perfectionism, but smaller than the traditional eating disorder intervention for objective binge episodes, and equivalent for reducing purging and the global eating pathology. In particular, the perfectionism treatment demonstrated very large effect size for concerns about shape and weight, which represents one of the core aspects of eating disorder psychopathology.

While the majority of research examining perfectionism interventions resides in the treatment literature, one study has investigated this from a prevention perspective. Wilksch, Durbridge and Wade (2008) examined the benefits of a program targeting perfectionism in reducing eating disorder risk in high school females (mean age 15 years). Students participated in an eight-lesson program targeting perfectionism or media literacy, or classes as usual. Although neither program produced significant interaction effects of group and time for shape and weight concern, the perfectionism intervention had a greater impact on individuals at high risk for an eating disorder than either the media literacy or control groups at 3-month follow-up. Most promisingly, for those students with high levels of weight and shape concern who received the perfectionism intervention, positive rates of clinically significant improvement were observed for all variables beyond chance. In particular, more than half of these students experienced improvements in perfectionism (both PS and EC) and dieting, while only one participant experienced increased risk.

Altogether, the wider body of evidence indicates that perfectionism is not a stable trait but is malleable and sensitive to clinical interventions. Preliminary studies show promise that by reducing perfectionism, risk for nontargeted disorders including eating disorders may be reduced, and existing symptoms may also be improved while not being the primary focus of treatment.

Future Directions

While there has been a long history of linking perfectionism with eating disorders, and perfectionism appears in many theories explaining the aetiology and maintenance of eating disorders, compelling evidence relating to the direction of causality is only starting to appear in recent years. Two main issues require further clarification. First, we need to develop a better understanding of how perfectionism may increase risk for the development of an eating disorder, and second, we need to develop a better understanding of the comparative importance of modifying perfectionism in both prevention and treatment of eating disorders compared to other risk and maintenance factors.

With respect to this first issue, a number of specific questions need to be investigated. First, we need a better understanding of which perfectionism constructs relate to the development of different types of disordered eating in longitudinal studies. Various measures tapping into different perfectionism constructs exist, and the most useful measures in terms of predicting the development of disordered eating need to be identified. Second, further work is required to develop and test complex models that explain how perfectionism may increase risk for disordered eating. This will involve both exploration of potential moderators (for whom and under what conditions perfectionism becomes a risk factor) and mediators (mechanisms through which perfectionism exerts an effect on disordered eating). In particular, clearer identification of protective factors that can ameliorate the adverse effects of perfectionism is required, with a particular focus on self-efficacy and feelings of effectiveness. Third, longitudinal research is needed across different ages and populations, including young males, transition to adolescence, transition to adulthood and older women. It is likely that different models explaining the way in which perfectionism increases risk for disordered eating are required for these different groups.

The second issue, relating to the role of targeting perfectionism in interventions, is also associated with a number of specific questions that need to be addressed. First, more experimental studies are required to better understand the different ways in which manipulating perfectionism can change risk for disordered eating. Second, dismantling treatment studies are required to investigate the degree to which a focus on decreasing perfectionism can hasten and enhance recovery from an eating disorder. Third, matching of the format (online, guided, face to face) and content of perfectionism interventions is required. This will involve consideration of treatment moderators (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002), that is, characteristics of the person who responds best to different formats and content. Fourth, more work is required in prevention with young adolescents and adults to understand the comparative importance of tackling perfectionism as opposed to other important risk factors for disordered eating.

References

Anderluh, M., Tchanturia, K., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Collier, D., & Treasure, T. (2009). Lifetime course of eating disorders: Design and validity testing of a new strategy to define the eating disorder phenotype. Psychological Medicine, 39, 105–114.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., Abramson, L. Y., Vohs, K. D., Heatherton, T. F., & Joiner T. E. (2006). Predicting bulimic symptoms: An interactive model of self-efficacy, perfectionism, and perceived weight status. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 27–42.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Frost, R. O., Bulik, C. M., Mitchell, J. E., Uppala, S., & Simonich, H. (2007). Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 384–405.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., Joiner, T. E., Crosby, R. D., Crow, S. J., Klein, M. H., le Grange, D., & Wonderlich, S. A. (2008). Examining a psychosocial interactive model of binge eating and vomiting in women with bulimia nervosa and subthreshold bulimia nervosa. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 887–894.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., Sturm, K., Lawson, M. A., Robinson, D. P., & Smith, R. (2010). Perfectionism across stages of recovery from eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43, 139–148.

Bastiani, A. M., Rao, R., Weltzin, T., & Kaye, W. H. (1995). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17(2), 147–152.

Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2004). Perfectionism, cognition, and affect in response to performance failure vs. success. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22(4), 297–324.

Besser, A., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Guez, J. (2008). Perfectionism, and cognitions, affect, self-esteem, and physiological reactions in a performance situation. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26(3), 206–228.

Boone, L., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Goossens, L. (2010). An empirical typology of perfectionism in early-to-mid adolescents and its relation with eating disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(7), 686–691.

Boone, L., Soenens, B., & Luyten, P. (2014). When or why does perfectionism translate into eating disorder pathology? A longitudinal examination of the moderating and mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 412–418.

Boone, L., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Braet, C. (2012). Is there a perfectionist in each of us? An experimental study on perfectionism and eating disorder symptoms. Appetite, 59, 531–540.

Boone, L., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Verstuyf, J. (2012). Self-critical perfectionism and binge-eating symptoms: A longitudinal test of the intervening role of psychological need frustration. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61, 363–373.

Bruch, H. (1974). Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa and the person within. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bulik, C. M., Tozzi, F., Anderson, C., Mazzeo, S. E., Aggen, S., & Sullivan, P. F. (2003). The relation between eating disorders and components of perfectionism. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(2), 366–368.

Byrne, S. M., Fursland, A., Allen, K. L., & Watson, H. (2011). The effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders: An open trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), 219–226.

Clausen, L., Rosenvinge, J. H., Friborg, O., & Rokkedal, K. (2011). Validating the EDI-3: A comparison of 561 female eating disorder patients and 878 females from the general population. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 101–110.

Cockell, S. J., Hewitt, P. L., Seal, B., Sherry, S., Goldner, E. M., Flett, G. L., & Remick, R. A. (2002). Trait and self-presentational dimensions of perfectionism among women with anorexia nervosa. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 745–758.

Cooper, P. J. & Fairburn, C. G. (1993). Confusion over the core psychopathology of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 13, 385–389.

Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Mitchie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655.

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., Conti, M., Doll, H., & Fairburn, C. G. (2013). Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 82(6), 390–398.

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., Doll, H. A., & Fairburn, C. G. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: an alternative to family therapy? Behaviour research and therapy, 51(1), R9–R12.

Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., & Shafran, R. (2011). Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(2), 203–212.

Fairburn, C. G. (1997). Eating disorders. In D. M. Clark & C. G. Fairburn (Eds.), Science and practice of cognitive behaviour therapy (pp. 209–241). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370.

Fairburn, C. G., Welch, S. L., Doll, H. A., Davies, B. A., & O’Connor, M. E. (1997). Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: A community-based case control study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 509–517.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., & Welch, S. L. (1999). Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: Three integrated case-control comparisons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(5), 468–476.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour research and therapy, 41(5), 509–528.

Fairburn, C., Cooper, Z., Doll, H., O’Connor, M., Bohn, K., Hawker, D., Wales, J. A., & Palmer, R. (2009). Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(3), 311–319.

Fairburn, C. G., Bailey-Straebler, S., Basden, S., Doll, H. A., Jones, R., Murphy, R., & Cooper, Z. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour research and therapy, 70, 64–71.

Field, A., Javaras, K. M., Aneja, P., Kitos, N., Camargo, C. A., Taylor, C. B., & Laird, N. M. (2008). Family, media, and peer predictors of becoming eating disordered. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 162, 574–579.

Forbush, K., Heatherton, T. F., & Keel, P. K. (2007). Relationships between perfectionism and specific disordered eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(1), 37–41.

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468.

Goldstein, M., Peters, L., Thorton, C. E., & Touyz, S. W. (2014) The treatment of perfectionism within the eating disorders: A pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(3), 217–221.

Gustafsson, S. A., Edlund, B., Kjellin, L., & Norring, C. (2009). Risk and protective factors for disturbed eating in adolescent girls—aspects of perfectionism and attitudes to eating and weight. European Eating Disorders Review, 17, 380–389.

Halmi, K. A., Sunday, S. P., Strober, M., Kaplan, A., Woodside, D. B., Fichter, M., et al. (2000). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: Variation by clinical subtype, obessionality, and pathological eating behaviour. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1799–1805.

Halmi, K. A., Bellace, D., Berthod, S. A., Ghosh, S., Wade, B., Brandt, H. A., Bulik, C. M., Crawford, S., Fichter, M. M., Johnson, C. L., Kaplan, A., Kaye, W. H., Thornton, L., Treasure, J., Woodside, B. D., & Strober, M. (2012). An examination of early childhood perfectionism across anorexia nervosa subtypes. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(6), 800–807.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456–470.

Jacobi, C., Hayward, C., de Zwaan, M., Kraemer, H. C., & Agras, S. (2004). Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin, 130(1), 19–65.

Jacobs, M. J., Roesch, S., Wonderlich, S. A., Crosby, R., Thornton, L., Wilfley, D. E., Berrettini, W. H., Brandt, H., Crawford, S., Fichter, M. M., Halmi, K. A., Johnson, C., Kaplan, A. S., Lavia, M., Mitchell, J. E., Rotondo, A., Strober, M., Woodside, D. B., Kaye, W. H., & Bulik, C. M. (2009). Anorexia nervosa trios: Behavioral profiles of individuals with anorexia nervosa and their parents. Psychological Medicine, 39, 451–461.

Kaye, W. H., Wierenga, C. E., Bailer, U. F., Simmons, A. N., & Bischoff-Grethe, A. (2013). Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels: The neurobiology of anorexia nervosa. Trends in Neurosciences, 36, 110–120.

Kobori, O., Hayakawa, M., & Tanno, Y. (2009). Do perfectionists raise their standards after success? An experimental examination of the revaluation of standard setting in perfectionism. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40, 515–521.

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomised clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 877–883.

Leon, G. R., Fulkerson, J. A., Perry, C. L., Keel, P. K., & Klump, K. L. (1999). Three to four year prospective evaluation of personality and behavioral risk factors for later disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(2), 181–196.

Lilenfeld, L. R., Stein, D., Bulik, C. M., Strober, M., Plotnicov, K., Pollice, C. et al. (2000). Personality traits among currently eating disordered, recovered and never ill first-degree relatives of bulimic and control women. Psychological Medicine, 30, 1399–1410.

Lilenfeld, L. R. R., Wonderlich, S. A., Riso, L. P., Crosby, R., & Mitchell, J. (2004). Eating disorders and personality: A methodological and empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 299–320.

Lloyd, S., Fleming. C., Schmidt, U., & Tchanturia, K. (2014). Targeting perfectionism in anorexia nervosa using a group-based cognitive behavioural approach: A pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(5), 366–372.

Lloyd, S., Schmidt, U., Khondoker, M., & Tchanturia, K. (2014). Can psychological interventions reduce perfectionism? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, available on CJO2014. doi:10.1017/S1352465814000162.

Machado, B. C., Gonçalves, S. F., Martins, C., Hoek, H. W., & Machado, P. P. (2014). Risk factors and antecedent life events in the development of anorexia nervosa: A Portuguese case control study. European Eating Disorders Review, 22, 243–251.

Mackinnon, S. P., Sherry, S. B., Grahma, A. R., Stewart, S. H., Sherry, D. L., Allen, S. L., Fitzpatrick, S., & McGrath, D. S. (2011). Reformulating and testing the perfectionism model of binge eating among undergraduate women: A short-term, three-wave, longitudinal study. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 58, 630–646.

McIntosh, V. V., Jordan, J., Carter, F. A., Luty, S. E., McKenzie, J. M., Bulik, C. M., Frampton, C. M., & Joyce, P. R. (2005). Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: A randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 741–747.

Pike, K. M., Hilbert, A., Wilfley, D. E., Fairburn, C. G., Dohm, F.-A., Walsh, B. T., & Striegel-Moore, R. (2008). Toward an understanding of risk factors for anorexia nervosa: A case-control study. Psychological Medicine, 38(10), 1443–1453.

Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 343–366.

Schmidt, U., Oldershaw, A., Jichi, F., Sternheim, L., Startup, H., McIntosh, V., Jordan, J., Tchanturia, K., Wolff, G., Rooney, M., Landau, S., & Treasure, J. (2012). Out-patient psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, 392–399.

Schmidt, U., Wade, T. D., & Treasure, J. (2014). The Maudsley Model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA): Development, key features and preliminary evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28, 48–71.

Shafran, R., & Mansell, W. (2001). Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(6), 879–906.

Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773–791.

Shafran, R., Lee, M., Payne, E., & Fairburn, C. G. (2006). The impact of manipulating personal standards on eating attitudes and behaviour. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(6), 897–906.

Shaw, H. E., Stice, E., & Springer, D. W. (2004). Perfectionism, body dissatisfaction, and self-esteem in predicting bulimic symptomatology: Lack of replication. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36, 41–47.

Sheldon, K., & Hilpert, J. (2012). The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: An alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction. Motivation and Emotion, 36(4), 439.

Slade, P. (1978). Towards a functional analysis of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21, 167–179.

Srinivasagam, N. M., Kaye, W. H., Plotnicov, K. H., Greeno, C., et al. (1995). Persistent perfectionism, symmetry, and exactness after long-term recovery from anorexia nervosa. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(11), 1630–1634.

Steele, A. L., & Wade, T. D. (2008). A randomised trial investigating guided self-help to reduce perfectionism and its impact on bulimia nervosa: A pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(12), 1316–1323.

Steele, A., Corsini, N., & Wade, T. D. (2007). The interaction of perfectionism, perceived weight status and self-esteem to predict bulimic symptoms: The role of ‘benign’ perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1647–1655.

Sternheim, L., Startup, H., Saeidi, S., Morgan, J., Hugo, P., Russell, A., & Schmidt, U. (2012). Understanding catastrophic worry in eating disorders: Process and content characteristics. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 1095–1103.

Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848.

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 295–319.

Stoeber, J., Hutchfield, J., & Wood, K. V. (2008). Perfectionism, self-efficacy, and aspiration level: Differential effects of perfectionistic striving and self-criticism after success and failure. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(4), 323–327.

Tissot, A. M., & Crowther, J. H. (2008). Self-orientated and socially prescribed perfectionism: Risk factors within an integrative model for bulimic symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(7), 734–755.

Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2013). The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: A summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. Journal of Eating Disorders, MS ID: 814225172874100.

Vohs, K. D., Bardone, A. M., Joiner, T. E., Abramson, L. Y., & Heatherton, T. F. (1999). Perfectionism, perceived weight status, and self-esteem interact to predict bulimic symptoms: A model of bulimic symptom development. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(4), 695–700.

Vohs, K. D., Heatherton, T. F., & Herrin, M. (2001). Disordered eating and the transition to college: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 280–288.

Vohs, K. D., Voelz, Z. R., Pettit, J. W., Bardone, A. M., Katz, J., Abramson, L. Y., Heatherton, T. F., & Joiner, T. E. (2001). Perfectionism, body dissatisfaction, and self-esteem: An interactive model of bulimic symptom development. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(4), 476–497.

Wade, T. D., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Shared genetic and environmental risk factors between undue influence of body shape and weight on self-evaluation and dimensions of perfectionism. Psychological Medicine, 37, 635–644.

Wade, T. D., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2011). A case series evaluation of the Maudsley Model for treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 382–389.

Wade, T. D., Wilksch, S. M., Paxton, S. J., Byrne, S. M., Austin, S. B. (submitted). How perfectionism and ineffectiveness influence growth of eating disorder risk in young adolescent girls. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 66, 56–63.

Watson, H. J., Steele, A. L., Bergin, J. L., Fursland, A., & Wade, T. D. (2011). Bulimic symptomatology: The role of adaptive perfectionism, shape and weight concern, and self-esteem. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 565–572.

Westerberg, J., Edlund, B., & Ghaderi, A. (2008). A 2-year longitudinal study of eating attitudes, BMI, perfectionism, asceticism and family climate in adolescent girls and their parents. Eating and Weight Disorders, 13, 64–72.

Westerberg-Jacobson, J., Edlund, B., & Ghaderi, A. (2010). Risk and protective factors for disturbed eating: A 7-year longitudinal study of eating attitudes and psychological factors in adolescent girls and their parents. Eating and Weight Disorders, 15, e208–e218.

Wilksch, S. M., & Wade, T. D. (2010). Risk factors for clinically significant importance of shape and weight in adolescent females. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 206–215.

Wilksch, S. M., Durbridge, M. R., & Wade, T. D. (2008). A preliminary controlled comparison of programs designed to reduce risk of eating disorders targeting perfectionism and media literacy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 939–947.

Williams, S. E., Watts, T. K. O., & Wade, T. D. (2012). A review of the definitions of outcome used in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 292–300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wade, T., O’Shea, A., Shafran, R. (2016). Perfectionism and Eating Disorders. In: Sirois, F., Molnar, D. (eds) Perfectionism, Health, and Well-Being. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18582-8_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18582-8_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18581-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-18582-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)