Abstract

The concepts of intergenerational equity, relational reciprocity and the dynamics of familial caregiving have long been a source of inquiry for social scientists, health care advocates and wellness experts. Like knowledge of the various dementias themselves, the body of information about the perceived experience of caring for a family member(s), with an Alzheimer’s type dementia, has been amassed over the last 20 years.

This chapter will discuss the profile of the contemporary family caregivers for persons with cognitive impairment. It briefly surveys the diversity that exists, among people who assume, or inherit a caring or care coordination role within a family. Commonalities, shared experiences and normative benchmarks for the likely course of caring for a cognitively impaired family member will be examined from six perspectives using the words of actual families it illustrates the realities of dementia care. These perspectives are physical care, lifestyle changes, emotional and psychological needs of the ill person and their carers, relational changes, pragmatic (legal and financial) dimensions and ethical decision-making dilemmas. The phases families encounter, during a journey with dementia, parallels the progression of illness over time, and has been referred to, in lay person terms, as “First Fear to Last Tear” [Bretcher (Alzheimer’s Association, Saint Louis Chapter; 2013)]. The impact on caregivers, from disease related experiences, across the continuum of long term dementia care, will be examined in terms of their negative or positive influence on well-being.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s care

- Care of persons with dementia

- Care partners

- Caregiving experiences

- Caregiving families

- Supporting families in dementia care

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter readers will be able to:

-

1.

Identify the influence of gender, gender identity, relationship status, ethnicity, the stage of dementia and the use of health care settings upon the caregiving experience.

-

2.

Examine factors that contribute to adverse and positive experiences of providing care for a person with dementia over time.

-

3.

Cite evidence for the scope, societal value and costs of family care for those with dementia.

Who Are Today’s Dementia Family Caregivers?

Millions of people worldwide are family caregivers supporting persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias such as Lewy Bodies that cause attendant changes in memory, judgment, behavior, thinking and function. These same caregivers are fighting daily to assure a person-centered approach: i.e., care that upholds the dignity, life story, personhood, humanity, well-being, comfort and core identity of those affected [1]. In this chapter, caregiving refers to attending to another individual’s health needs without pay to include assistance with one or more activities of daily living (ADLs; such as bathing and dressing) as well as, extensive help with Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) such as money management, shopping, home maintenance [2]. The term care partners refers to family members or members of intentional kinship networks such as friends, members of faith communities and extended social or work related relationships. In the early stages of the disease, caregiving may lend itself to more mutual cooperation and shared responsibility; thus, creating partners in care, or care partners. Later in the disease, carers take on more of the surrogate decision-making and hands on, physical care roles.

Caregiving Facts and Figures

In 2013, 15.5 million American caregivers provided an estimated 17.7 billion hours of unpaid care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, valued at more than $220 billion. Eighty-five percent of help provided to all older adults in the United States is from family members [3]. Additionally, caregivers of people with dementia spend more hours per week providing care than non-dementia caregivers. Additionally, they report greater employment complications, caregiver strain, mental and physical health problems, family time and less time for leisure [4]. The unique characteristics of those caring for people with dementia and their challenges are explored in this chapter.

Complex Composition of Caregivers

Caregivers come from many ethnic backgrounds, socioeconomic strata, communities, environments and family situations. There are many diversity factors to consider when profiling the caregiving population. Some less referred to in the literature include: sexual orientation or identity, employment status, distance carers, new Americans, those in military service, caring for a developmentally disabled elder or members of religious communities such as Catholic Sisters and Brothers. Those caring for more than one loved one with dementia is also expanding [5]. Data that summarizes some of these groups and caregiving relationships with the person with dementia is explored below.

Women as Caregivers

There are 2.5 times more women than men providing intensive “on-duty” care 24 h a day for someone with Alzheimer’s. More than 60 % of Alzheimer’s and dementia caregivers from the above categories are women. In 2009–2010 caregiving data was collected in eight states and the District of Columbia from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys. It indicates 65 % of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias were women; 21 % were 65 years old and older; 64 % were currently employed, a student or a homemaker; and 71 % were married or in a long-term relationship [6]. Women’s roles in caregiving are a significant focus for new research and resources. While many provide care for a family member, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, women are still at the epicenter of the growing Alzheimer’s epidemic [7]. As indicated in Table 1, the burdens of female caregivers are heightened by the amount of time they spend with the person with dementia.

The typical family caregiver is a 49-year-old woman caring for her widowed 69-year-old mother who does not live with her. She is married and employed. Approximately 66 % of family caregivers are women. More than 37 % have children or grandchildren under 18 years old living with them [8]. National averages predict that women will spend an average of 27 combined years caring for children and parents over the course of their lifetime. As availability of earlier diagnosis and treatments that may work to plateau symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in some, become the norm, female carers could spend closer to 40 years in these roles either sequentially or simultaneously [9].

Men as Caregivers

Approximately 14.5 million caregivers are men. Male caregivers are less likely to provide personal care, but 24 % helped a loved one get dressed compared to 28 % of female caregivers; 16 % of male caregivers help with bathing versus 30 % of females. 40 % of male caregivers use paid assistance for a loved one’s personal care (The National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP 2012). A national study of male caregivers revealed that the average male caregiver was a white, protestant, middle class, moderately well-educated, retired man who was 68 years old. Most caregivers were husbands taking care of their wives [10]. This may account for the lack of information regarding other male caregivers, such as sons.

Additional research regarding male caregiving is needed. In particular, research fully linking men’s caregiving, to men’s health issues as a means to articulate strategies to sustain the health and well-being of male caregivers. This seems especially relevant in light of the closing gender gap in life expectancy, which will ultimately see many men providing direct care to their partners [11].

Results of the 2014 Alzheimer’s Association Women and Alzheimers Poll indicate that male caregivers are more likely to share the caregiver burden [2]. Participants of Male Caregiver Groups sponsored around the country by Alzheimer’s Association chapters and other organizations, report perceptions of lowered stress and isolation and greater access to useful information than peers that do not participate in such groups.

Spouses as Caregivers

Caregiving for a spouse with dementia brings specific relational challenges. Many spouses experience denial which may be a beneficial coping mechanism as they become educated about the anticipated anguish and reality of what Alzheimer’s will mean to their relationship. The spousal relationship will change throughout the course of the disease. Roles, responsibilities and intimacy will all begin to look different as the disease progresses [12]. Subtle adaptations may turn into major lifestyle and relational changes. Social transitions will occur as couples try to maintain friendships and networks. Spouses are the most likely caregivers to live 24/7 with the person with dementia. They may feel uniquely overburdened because they find it difficult to get away from the home, to take a break and to care for themselves. All caregivers struggle with the balance of caring for the person with dementia and caring for themselves. This struggle may have dramatic consequences. The Journal of American Medical Association reports that if you are a spousal caregiver between the ages of 66 and 96, and are experiencing ongoing mental or emotional strain as a result of your caregiving duties, there’s a 63 % increased risk of dying over those people in the same age group who are not caring for a spouse. This indicates the urgent need for caregiving spouses to find resources and support [13].

Children and Others as Caregivers

Society well recognizes the role spouses often play as providers of care for persons with dementia, but providers in the field similarly observe, children, stepchildren, former spouses, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, siblings, friends, intentional family members, partners and even parents involved in some aspects of the caregiving role. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), based on a nationally representative subsample of older adults from the Health and Retirement Survey, indicates over half of primary caregivers (55 %) of people with dementia took care of parents [14]. They may be assisted by a variety of “adjuncts” such as care managers, trust officers and legal guardians as well as a host of paid caregivers. Many children report the benefits of caring for their parent, including bringing the family closer and feeling good about taking care of someone. However, complications of caring for parents can include, struggling with role reversal, unresolved familial issues and resentment. Because adult children are the largest group of carers for people with dementia, there are many support groups, blogs and resources to provide support.

Club Sandwich Generation Caregivers

The “sandwich generation caregiver” is a nomenclature that has described a mid-life person who simultaneously cares for dependent minor children and aging parents. But the phenomenon of sandwich generation is now becoming more nuanced and multi-generational. A 65 year old may have a 90 year old parent, and also may have responsibilities for multiple elders in their family such as care of in-laws, middle aged children, grandchildren and even great-grandchildren. An 80 year old may have a 100 year old parent and a 60 year old adult child and all three generations suffer with a variety of comorbid, age related conditions. Data from recent years suggest that demographic changes (such as parents of dependent minors being older than in the past and the aging in general of the U.S. population) have led to increases in the number of what these authors call “Club Sandwich Families”; family members involved in three or more layers of familial caregiving. This is not unique to dementia care, but given that prevalence is on a dramatic rise, one can expect to see club sandwich generation caregivers growing as well. It is known that 30 % of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia caregivers had children under 18 years old living with them [8, 15]. About one-third of elderly care recipients have Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia [8]. Studies have found that sandwich generation caregivers are present in 8–13 % of households in the United States [16]. Studies concur that sandwich generation caregivers experience unique challenges related to the demands of providing care for both aging parents and dependent children. Such challenges include limited time, energy and financial resources [17, 18]. This leads to conjecture that “club sandwich caregivers” may be at exceptional risk for anxiety, depression and lower well-being due to the unique challenges these individuals experience [19].

Parents as Caregivers: When Your Child Has Dementia

As persons have access to more timely and accurate diagnosis, leading to earlier identification of dementia, parents of early onset individuals are also seen providing or coordinating care. Evidence-based information on this growing trend is lacking in the literature. It is a very difficult scenario as this may take place at a time of diminished health and financial resources for that parent. If other children, or spouses are available, they may find themselves sharing the care and supporting the grieving parent as a co-caregiver, adding to the collective familial stress.

Evidence is just emerging on the relatively newly recognized phenomenon of parents of individuals with Down syndrome (DS), who are at especially high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. These parents in their 60s–80s may find themselves caring for a developmentally disabled adult with Alzheimer’s disease. They may be particularly ill prepared for this possibility due to the lack of good medical care or cognitive screenings for persons aging with Down syndrome. Plus, information and education about the DS Alzheimer’s risk factor is only recently being disseminated more widely by groups such as the National Association on Down Syndrome, the National Down Syndrome Society and the National Alzheimer’s Association. Special care environments for these individuals are virtually lacking. Estimates show that Alzheimer’s disease affects about 30 % of people with Down syndrome in their 50s. By their 60s, this number comes closer to 50 % [20]. Only 25 % of persons with DS live more than 60 years, and most of those have AD. Individuals with Down syndrome develop AD symptoms identical to those described in individuals without DS. Given the early age of onset (40s–50s) of AD in individuals with DS, their parents in their 70s and 80s may be navigating the difficult waters of getting accurate diagnosis for their adult child in a health care system not prepared for this presentation [21]. These caregivers fight a battle of poor awareness, few appropriate medical services or knowledgeable professionals available to guide them. They also deal with the highly possible reality of outliving their child with AD [22].

Employed Caregivers

Another important aspect of caregiving to examine is employment status. Interestingly, working and non-working adult children are almost equally as likely to be caregivers. Eighty-one percent of Alzheimer’s caregivers under the age of 65 are employed. Thirty-five percent of those over age 65 were employed while caregiving [8]. As the baby boomers postpone their retirement, the number of caregivers working into later years from 66 to 70+, will likely increase. Caregiving in any age group often means adjustments to work schedules are necessary, which may lead to job insecurity and elevated stress for caregivers. Table 2 indicates some of the consequences of juggling work and caregiving. Early retirement rates or breaks in employment to provide care, are also more prevalent in carers of people with dementia. It is reasonable to consider that these demands will affect the caregiver’s economic status for years to come. The total estimated lost wages, pension and social security benefits of these caregivers are nearly $3 trillion. The estimated impact on lost Social Security benefits for the average caregiver is $303,000 [23].

While working and non-working adult children are almost equally as likely to provide care, adult children 50 and over who work, are more likely to have poor health than those who are not caregivers [23].

Long Distance Caregivers

Long distance caregiving can add unique and complicated challenges to an already stressful and emotional situation. Studies have defined a long distance caregiver in different ways. Some suggest the term apply to caregiving from 100 miles or more away from the person with dementia. Others indicate that the most important factor to define, is the amount of time it takes to travel to the person requiring care. Those studies propose that living an hour or more away constitutes a long distance caregiver.

Clearly long distance caregivers enlist the aid of others to provide the daily care of the person with dementia. Often, the long distance caregiver is not the primary caregiver, but plays the role of a counselor, helper or source of respite. Long distance caregivers who are the primary caregivers, 5 %, depend more heavily on paid caregivers. It has been estimated that long distance caregiving costs twice as much as for those more proximate [24]. Additionally, these caregivers may spend more time away from other family, friends, work and home life as they travel frequently to see their loved one.

Families with special needs for caregiving support include those who may be deployed in or out of country due to military service, those who work overseas for non-governmental entities or work in a foreign country for international firms. As our world shrinks and becomes more interdependent, this group of long distance caregivers, coupled with the boomers anticipated needs for dementia care, raises both ethical and logistical questions. With the number of long distance caregivers increasing, it is important to explore resources and accessible support to these individuals. There may be some offset for these caregivers by other members of the family such as adult children moving back in with a demented parent for both economic and caregiving reasons as alluded to earlier in this chapter. Technology also holds promise for the possibility of closer communication between geographically dispersed caregivers and their loved one with AD. The availability of safety tracking systems, visual viewing, cueing and monitoring devices may become more affordable and routine for popular use.

Ethnic Diversity Factors

Diversity among caregivers is an important factor to consider. African-Americans, are two times more likely to develop late-onset alzheimer’s disease than whites and less likely to have a diagnosis of their condition, resulting in less time for treatment and planning. Clearly, this will impact the African-American caregivers stress and access to resources and support. A 2006 analysis [25] on caregivers of African-Americans with dementia, found that African-American primary caregivers are more likely to be adult children, extended family or friends rather than spouses who constitute the primary caregiver norm for white counterparts. She summarizes various studies on the explanatory models and strong cultural expectations around care of African-Americans with dementia. Lower use of formal care supports or long term care settings in this population has been well documented. Other recent research, about perceptions of African-American carers, regarding role strain versus positive aspects of caregiving report contrasting results. Some indicators propose that African-Americans find caregiving more rewarding than whites, while other studies demonstrate a wide range of psychological burden especially among higher educated female caregivers [26]. Among caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP found the following [14].

-

Fifty-four percent of white caregivers assist a parent, compared with 38 % of individuals from other racial/ethnic groups.

-

On average, Hispanic and African-American caregivers spend more time caregiving (approximately 30 h/week) than non-Hispanic white caregivers (20 h/week) and Asian-American caregivers (16 h/week).

-

Hispanic (45 %) and African-American (57 %) caregivers are more likely to experience high burden from caregiving than whites (33 %) and Asian-Americans (30 %).

Data collection around many other groups of caregivers such as, Asian-American, new immigrant populations and among non-English speaking populations is scarce, but emerging.

Caregiving for and by LGBT Community

Often lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) individuals have experienced challenges with family, friends, employers and service providers. This experience may create unique challenges for these caregivers. For example, LGBT individuals may seek medical care less regularly due to fear of inadequate treatment or discrimination. Regardless, a recent survey indicated respondents who were lesbian, gay, bi-sexual or transgendered were more likely than other respondents to have cared for an elderly family member in the last 6 months [27].

In a MetLife study, both men and women are likely to be caregivers in near equal proportions: 20 % men vs. 22 % women in the LGBT group, and 17 % men vs. 18 % women in the general population sample. Male caregivers report providing more hours of care than female caregivers: the average weekly hours of care provided by women from both the LGBT and general population samples is similar—26 vs. 28 h—but LGBT men provide far more hours of care than men from the comparison sample: 41 vs. 29 h. This reflects that about 14 % of the gay men indicate that they are full-time caregivers, spending over 150 h/week in this capacity, compared to 3 % of the lesbian and 2 % of the bisexual respondents [28].

As we explore diversity and relationships among caregivers there are a vast number of “invisible” or less visible sub-groups. There are many diverse groups not discussed in detail here; such as, vowed religious, military personnel, divorced spouses, former in-laws, and non-related caregivers. The key is recognizing that caregivers are extremely heterogeneous and each category bring their unique relationships, values, perspectives, history and beliefs to their caregiving experience.

Likely Course of the Caregiving Experience: A Family Disease Perspective—The First Fear to Last Tear Phases

Due to the slow, insidious progression of Alzheimer’s and some other dementias, the duration of caregiving for these persons, averages 4–8 years after a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. As care improves and other wellness tactics are deployed it is not rare for otherwise healthy individuals to live as long as 15 or more years with dementia [29]. Table 3 illustrates the variations in the caregiving experience as the person with dementia moves through the disease process.

Physical Care

Though the care provided by family members of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is somewhat similar to the help provided by caregivers of people with other conditions, dementia caregivers tend to provide more extensive assistance. Family members of people with dementia are more likely than caregivers of other older people to assist with any activities of daily living (ADL). Physical care demands can be wide-ranging and in some instances all-encompassing. Table 4 summarizes some of the most common types of dementia care provided. More than half of dementia caregivers report routinely helping loved one’s getting in and out of bed, and about one-third provide help to their family member with dementia to locate and use the toilet, bathing, managing incontinence and assist with eating [8].

In the earliest phases of dementia, affected persons may not need physical care, but caregivers may notice worrisome signs of self-neglect or changes in personal grooming in their loved one. As caregivers notice things, like mom periodically sleeping in her street clothes at night or dad wearing the same stained slacks, they may become more physically involved with helping their loved one dress. Long distance caregivers may not have access to these clues to functional changes and most adult children are reluctant to comment or interfere with things as personal as grooming, dressing and bathing until absolutely necessary. Male spouses may be more sensitive to these subtle changes and assume a compensatory role in laying out clothing, helping with makeup and clothes shopping etc. In moderate stages, physical care demands become more difficult to ignore. The person with dementia may ask for needed help, but may also deny help, leading to stressful situations. As illness progresses physical care needs increase and are often provided in part by formal caregivers, like in home aides. Ideally this helps families “share the care” or provides respite. But in some circumstances the person with dementia will only accept care from their familiar loved one. Paid staff are often not available for care at night. Scheduling and oversight of paid, in-home workers could add a level of stress for the primary caregiver. During this phase, families learn to simplify many physical tasks, adapt the environment for both caregiver and person with dementia and limit choices to acceptable options. There is a great deal of information available through caregiving groups. However, little of this information provides specific breakdown of how to accomplish specific tasks, such as bathing, oral care, body mechanics and changing a bed with someone in it. Others learn to adapt and respond to physical care demands by trial and error. Few in home teaching resources for caregivers are available due in part to reimbursement and insurance funding mechanisms. Caregivers may actually find pride in the hands on care they provide, as they seek to retain their loved ones former appearance and preferences. However, if caregivers experience resistance or aggression from the person with dementia during personal care, the demands become both a source of physical and emotional drain for the care provider.

Physical decline is a risk for carers of people with dementia. Caregivers self-report a decline in their own health condition while caregiving. Their emergency room visits and use of hospital services increase 25 % while caregiving [30].

Families using supportive information learn to “choose their battles”, adapt expectations, simplify tasks and perform them in short spurts at the best time of day for the person with dementia. These techniques and others may mitigate the strain of providing physical care.

In the later stages of AD/related dementias caregivers have experienced the worst impacts of declining health. Often times family members provide care for their declining loved one beyond what is safe. Caregivers must assess their own physical ability to manage complete incontinence, poor ambulation, total dependent care so that the person with dementia and the carer remain safe. Many in the dementia care field have witnessed the not uncommon circumstance of the caregiver dying before the person with dementia. Roughly 30 % of caregivers die before their loved one [31]. This may leave a person with dementia without a caregiver or may require other family members to quickly assume this duty.

Advocacy roles may grow, but the physical care demands may be met in a way that now allows family caregivers to resume a more predictable work or social life, sleep better at night or take long-withheld vacations. Other families who are aware of, qualify and use hospice care for their loved one, may find relief at this stage from some of the physical care demands as they also receive emotional and spiritual support.

Lifestyle Changes

The psychological strains of caregiving have been measured in many ways [32]. Major disruptions in lifestyle, such as a caregiver relocating to be near the person with dementia or giving up employment to provide care are easily measured. The impact of more subtle changes in caregiver roles and activities are more difficult to gauge. In the first stages, caregivers may feel confused as their loved one seems to choose to engage in fewer shared activities or conversations. A caregiver may notice and grieve a change in spontaneity or enjoyment in the person with dementia. As care demands grow, caregivers may have to give up poker nights, bowling leagues, church or synagogue activities for fear of leaving the affected person alone, which can lead to social isolation, depression, and even resentment. A shift in who pays the bills or does the cooking, may feel uncomfortable or unfamiliar to the care partner taking on these tasks. The need to accompany the person with dementia to all medical appointments becomes time-consuming. Caregivers may then begin to neglect their own medical needs. Employed caregivers may experience lower work performance or work satisfaction and a more limited social life as weekends become absorbed with parent care responsibilities. Seeking to coordinate a patchwork of services for the person living with Alzheimer’s such as having them attend day programs or hiring in home help may be quite helpful, but can also change the rhythm and privacy in the caregiver’s life. The most commonly cited disruption in the mid-stage of illness is the impact on driving cessation. This can have major lifestyle repercussions for caregivers especially for those living in rural communities or in those families in which the person with dementia was the sole driver [33]. It is highly beneficial for families to seek advice, counsel, information and referral from groups such as AARP, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers and the Alzheimer’s Association to support them early on in the disease around matters such as driving, curtailment of leisure, locus of control issues and exhaustion from these disruptions. The families using these supports report high levels of satisfaction and relief when they are able to find social networks that foster positive changes in lifestyle, despite the disease [34].

In later stages of illness, especially when the person with dementia may have been moved to a care setting. Spouses or those living with the person with dementia, absorb the impact of lifestyle changes. But, these are not all negative. In some instances this can be a time to re-invest in neglected work life. Spouses that visit their loved ones often in “the Home” may become friendly with other frequent visitors, residents and staff. Support groups for those with family members in long term care may provide a therapeutic and social outlet. Remaining lifestyle stressors, may be affected by comorbid conditions that can result in numerous moves, rehabilitation stays or hospitalizations secondary to the primary dementia. Throughout the disease progression caregivers are called upon to frequently adapt their lifestyle based on the needs of the person with dementia.

Emotional Care

The emotional aspect of the journey with Alzheimer’s begins for family members in the “first fear stage.” Self-doubt about whether to seek assessment for a loved one is emotional. Some families have to contemplate and devise elaborate plans to even get a parent to see a physician. Many carers report that the diagnosis was communicated abruptly and without regard or support for the feelings of the person with dementia or their family. Anger, denial and confusion are common responses that can linger. Disease awareness and the normative experience of being a boomer generation caregiver has led to greater sense of empowerment of the caregiver. Caregivers are more likely now, than their counterparts 20 years ago, to understand Alzheimer’s and other dementias as a brain disorder rather than a preventable malady or mental illness. Unfortunately, 24 % of Americans still believe that Alzheimer’s disease is part of normal aging and that the disease is NOT fatal. But that number is decreasing as education and resources become more available [2]. Emotional support from peers who have already cared for an elder may be more available. As person centered care models and a culture shift in long term care environments has occurred, persons needing formal care may have more individualized, homelike and attractive environments in which to receive care. But many families still feel overwhelmed and guilt ridden when exploring care options. Early intervention such as receiving counseling for oneself as well as accessing expert and appropriate neurological care for the person with dementia can also diminish anxiety or guilt. Families provide care in the context of pre-existing relationships. The frustration and fear around just getting an accurate diagnosis may start a chain of feelings like “why didn’t I notice this sooner” or “… perhaps if I’d spent more time with mom”…etc. As difficult behaviors appear, caregivers may have a range of feelings from anger, ambivalence, hopelessness, loss of control about the disease and the changes the person with dementia is experiencing. Finally, any unresolved conflicts within family members are often visible as the need to communicate and coordinate care of the affected person places more emotional demands on the family network. Feelings may submerge and re-emerge during difficult decisions like moving to long term care or end of life decisions.

Grief can be anticipatory and extensive as the carer tries to respond emotionally to their loved ones diminished capacity and changes in appearance, personality and health status. Falls, accidents and hospitalizations all become mini-crisis that evoke feelings. Fear and lack of control are often reported by family caregivers, as well as regret that unresolved issues can never be addressed with the person losing their memory [2].

Behavioral changes requiring interventions are evidenced in 80–90 % of elders living with a dementia at some time during the course of the disease [35]. Caregivers may feel many emotions including embarrassment for behavioral symptoms. One of the most painful experiences families report is watching a loved one display behavior the carer never would have thought possible, such as cursing or disrobing. It is particularly challenging when caring for persons with a frontotemporal dementia which has a more behavioral symptomatic presentation [36]. Carers may blame themselves for these challenging behaviors. Many families find ways to modify or better accommodate behaviors by creating a more “forgiving or failure free” environment or adapting the way they communicate with their loved one with dementia. Others may seek emotional support through counseling, or pastoral guidance, which may make a substantial difference in stress and perception of burden.

At the later stage, families may be more knowledgeable about disease progression, may have received some formal counseling, and may have begun to utilize services that support the caregivers emotional healing. At the end of life, depending on the situation, families may still report loneliness and some fear of the unknown, but also feelings of relief, pride, reflection and closure.

Relational Dynamics

Caregiving for a loved one is accompanied by the interpersonal relationship that existed prior to dementia and caregiving. Certainly this complicates the relationship between care partners. If a relationship was without much strain before caregiving began, it is likely that the caregiving relationship can develop without intense issues. Conversely, when caregiving happens in an already strained relationship the challenges can quickly multiply [37].

In the early stages of the disease, caregivers may feel concerned about crossing an unspoken boundary. Their loved one is an adult and it can be stressful deciding when to begin assisting with decision making and caregiving. This stage can create strain if the person with dementia feels disrespected or undervalued. Decreasing decision making skills on the part of the person with dementia adds tension as the caregivers concerns over safety rise. As the person with dementia experiences cognitive decrements, the role of the caregiver as decision maker, becomes clearer and can lessen the relationship burden. Behavior issues are common and add tension to the relationship as caregivers try to understand and prevent challenging behaviors [38]. In the last stages of Alzheimer’s disease, relationship strain decreases as caregivers have some resolve with their role and relationship shifts. Yet, strain that existed prior to caregiving may remain unresolved and unlikely to be settled for the caregiver. This may add to their grief and loss [39]. Support through family/friends, grief counseling and hospice services can help to ease this unresolved pain.

Practical Matters

Families step in to help the person with dementia with many essential affairs such as banking and finances, legal planning, accessing community resources, making end of life plans and adjusting living arrangements. Almost two-thirds of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s and other dementias advocate for their care recipient with government agencies and service providers (64 %), and nearly half arrange and supervise paid caregivers from community agencies (46 %) [8]. The task of managing practical matters may be a shared responsibility across several generations or may be managed by one key family member. Power of Attorney, health directives and other legal affairs need to be organized as early in the disease process as possible to assure the person with dementia has a voice, but this is not always possible. Many times adult children may be unaware of their parents’ financial and legal affairs or feel awkward bringing this topic up. Confusion, suspicion or family discord can add to the stress surrounding practical matters. There may be feelings of anger, disappointment and fear once caregivers determine the financial reality of caring for someone with an illness that lasts many years. Family members can be embarrassed or overwhelmed by their loved ones’ need to apply for public benefits. Often families are uninformed about eligibility and what Medicaid, Medicare, veterans benefits and long term care insurance covers.

Abuse is an important concern. One in nine seniors report being abused, neglected or exploited in the past 12 months; the rate of financial exploitation is extremely high, with 1 in 20 older adults indicating some form of perceived financial mistreatment in the recent past (National Adult Protective Services Association Internet). Consequently, some family members may also be concerned about others in or outside the family financially exploiting their loved one.

Some carers may place themselves in financial risk in an effort to help pay for the person with dementia’s care. Education and resources can assist with these complex practical concerns. Families may be so busy providing essential physical care that they have limited time and resources to investigate and plan around legal and financial matters or their parents may be reluctant to share needed documents and information. Early planning for these practical matters can reduce strain, cost and frustration for family caregivers.

Ethical Dilemmas

The last domain in this construct of Phases of Family Experience is ethical decision making. Family members may assist the person who has dementia with numerous decisions involving autonomy, self-determination, safety and risk throughout the disease process. Examples include: choosing medical practitioners, sharing the diagnosis, balancing risk with autonomy, determining capacity and competency and advocating for ethical care. The progressive nature of the disease makes decision-making a moving target. Particularly in situations involving early onset dementias, families have not typically had the crucial conversations that outline preferences for treatment, care and good death scenarios. Families generally want their loved one involved in decision making as long as possible. Degrees of capacity fluctuate for persons with dementia so a decision specific strategy is often engaged. Some tools caregivers use are advance directives, living wills, power of attorney for both financial and health related decisions, guardianship, conservatorship, Do Not Resuscitate orders and POLST guidelines (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment.) The legal nuances among these choices may vary from state to state impacting long distance caregivers and members of the LGBT community particularly. Few families will have formal training in medical ethics concepts such as surrogacy or best interest standards, but can generally discern concepts of consent, assent and dissent in practical caregiving situations. Viki Kind’s book, Caregiver’s Path to Compassionate Decision Making: Making Choices for Those Who Can’t [40] and the Group Principles outlined in the work of Beauchamp and Childress [41] may be consumer friendly resources for caring families.

Another issue caregivers’ may confront is lack of access to ethicists at crucial times such as during a hospital stay or a critical change in condition. Families planning ahead can educate and prepare themselves to engage with the person with dementia around those difficult decision such as when to stop driving, sell a home, apply for Medicaid or hospice care and when to end life sustaining treatments. Knowing what the person with dementia perceives as a good death while they are still able to express their opinion relieves doubt and provides comfort to families [42]. Caregivers may turn to advance counseling with pastoral care, care managers, social workers, elder law attorneys, Alzheimer’s Association Helplines and websites to prepare to make these ethical choices.

Family Perspectives Across the Care Continuum: Evidence Based Best Practices

Medical Care: Getting the Diagnosis

Awareness of Alzheimer’s disease is low, but growing. Persons that have a history in their family may be more aware of disease risks. Since Alzheimer’s disease occurrence is sporadic many caregivers are not prepared to seek diagnosis for their loved one. Despite concerns and episodes of memory loss, forgetfulness and accidents, most families report feeling guilty suggesting that a person seeks assessment. Additionally, it is often very difficult to convince a person with memory loss to seek diagnosis. Diagnosis may involve a trusted primary care physician or may be performed at a large and unfamiliar academic institution. Other challenges may include living in a community with few diagnostic resources, or physicians not familiar with diagnosing dementia. The best practices for diagnosis are outlined in the Alzheimer’s Association’s, Principles for a Dignified Diagnosis [43].

Some families experience conflict during diagnosis. For example, they may feel the diagnosis should be hidden from the affected person or its importance or significance downplayed by the practitioner. Some of the questions families have at this time of pre-post diagnosis are: Who should we to go to? Can I trust this doctor? Can I trust this diagnosis? Carers may not understand the steps in the diagnostic process or the purpose behind various tests leading to confusion about the results. They report the way the diagnosis was communicated was insensitive or hurried. While some families have a “can do” attitude and remain positive, doubts such as, I can’t do this alone, no one else understands what I am going through, or I’m sick too, arise. Adult children, especially those in the “club sandwich” generation report feeling overwhelmed. Families express frustration that no one has explained what to do next, what comes next or what the action steps are they are supposed to take now. They often have questions about the length and projection of the illness, which can be down played by some practitioners. They may be confused about the efficacy cost or side effects of medications and treatment. After the appointment where diagnosis is given, caregivers may leave, not understanding that they are dealing with a long term, terminal illness. Unfortunately, families may not find out about resources such as the Alzheimer’s Association until they have already experienced these situations. Hopefully, with advice from friends, clergy or health care providers, families reach out for the education and support that they will now need.

Using Community Education and Support Resources

Caregivers differ in their approach to accessing community education and support resources. They also differ in the relative value that they place on utilization. Some families may choose to “handle it on our own”. Others want to take full advantage of everything that is available [44]. One challenge for careers is the enormous amount of ever changing information about both the disease as well as treatment protocols. For example, information for families dealing with stroke, Parkinsons disease and AD related dementias may have to select among a vast array of information and education opportunities. Other caregivers such as those dealing with more rare dementias such as supranuclear palsy, Lewy body, Down syndrome associated dementia or frontal temporal lobe dementias may lack access to resources specific to their needs. Family members of younger onset individuals, affected by any type of dementia often feel that the information is skewed to an older population. Other real or perceived barriers may be living in a rural community, or technology limitations since many resources are now accessed or delivered online. Although some services for caregivers like support groups have been around for years, families may perceive attendance as one more task on their “to do” list. They may also have difficulty having someone stay with their loved one while they are out to attend education programs or they cannot use respite because their loved one is unaccepting of anyone else in the home. There is insufficient research about receiving information alone i.e., online, versus at an in person education or support group. Some families may perceive that they already know everything because of a previous caregiving experience thus missing out on newer services or technology supports.

Caring at Home-Community Care Services

When asked, most elders as well as their family members state they (the elder) prefers to remain at home or in the home of a family member. According to the Pew Research Center [45], 22 % of older women and 16 % of older men reside in multigenerational households. Families become increasingly aware that their loved ones’ decreased insight and judgment, poses many challenges for living totally alone. Home health care is more readily available to families, but vary in quality. More expensive private home care companies are innovating to provide more ala carte services such as pet care, transportation and hair care services. But the growing expense to families of providing in home oversight, to a live alone elder with cognitive impairment, is either unaffordable or does not provide the total piece of mind caregivers need.

According to Mollica [46], families often select home care first in hopes of avoiding moving to long term care and to lower costs. Caregivers of persons with dementia are often advised to avoid changes, maintain a familiar environment to retain a sense of lifestyle continuity. Services in the home may fit these criteria for varying periods of time. A family member residing with the memory impaired person, may decide that home care can no longer address increasing “nocturnal wandering”, severe incontinence and other symptom related behaviors such as aggressivity. In addition to financial and safety concerns the person with dementia may eventually lack of recognition and trust of the caregiver (family and/or paid). Families then ask: Where should my loved one with AD/dementia live? Is my loved one’s home or my home still appropriate? What is the practicality or financial impact of assuring in-home care is a safe, accessible environment for later stages of disease? Are family and other resources sufficient and proximate enough to sustain living at home? Should I relocate my loved one to a care center for more support? Asking these difficult but necessary questions, can cause stress for families or create conflict and divisions difficult to repair. This is when other options of care can be considered.

Care Management

Care management services broker and coordinate needed supports for family members caring for persons with dementia. While this is a growing resource, many families do not know about care management or cannot afford it. Care management may be delivered to carers from public, private non-profit, private for-profit or hospital, social services or home care affiliated organizations. Since care management is referred to by a number of names such as case coordination, case management or transitional care services, it may be confusing for some family members to identify. Long distance caregivers may be more likely to use this type of assistance to coordinate care and decisions about their loved one with dementia. Since awareness of case management resources is low among family members, they may feel guilty or inadequate if they have not discovered this resource earlier in the disease process. Use of care management represents another affordability decision at a time of scarce resources. Geriatric care managers provide initial assessments and assistance with care of a loved one including crisis management, interviewing in-home helpers, or assisting with placement in a long term care community. The evidence base for the efficacy of care management services is being established. Some family members may feel they do not need this outside assistance or should be providing all the care coordination themselves. Older spouses may not be comfortable using this relatively “new” service to support them in their caregiving role. This may change as medical homes and transitional care services are becoming a more entrenched standard of care.

Adult Day Care

Adult Day Service (ADS) centers offer a wide range of services for the person with dementia who lives in a private home. Typically ADS is sought by caregivers who are concerned about leaving their loved one at home alone. Or, it is often a great resource for improved social interaction or respite for the caregiver. For the caregiver of a person with dementia, running errands, spending social time with friends, or even personal hygiene can suffer because of the need for 24/7 supervision of their loved one. ADS can provide a break so that the caregiver can tend to needs that might otherwise not be possible. Family caregivers show an increase in the beneficial stress hormone DHEA-S on days when they use an adult day care service for their relatives with dementia, according to researchers at Penn State and the University of Texas at Austin (2014). While many families may have guilt about their loved ones it can be an essential piece to caring for the caregiver.

The Adult Day Centers also benefit the person with dementia. The increased social interaction, physical activity, and cognitive stimulation can improve the general welfare of the person with dementia. In contrast, ADS participants are more likely to experience behavior problems and poor sleep on days when they remained at home [47]. ADS programs are expanding and improving their models of care to meet the needs of people with dementia. They should be considered as a promising resource.

Assisted Living

Family caregivers may perceive the need for assisted living during the mid to later course of their family members’ illness. It is difficult to tell whether a parent, another family member or loved one needs more help. The following warning signs in the following figure have been suggested as indicators that additional formal support such as assisted living may be appropriate for an adult with cognitive impairment.

In the U.S., each state has its own definition or specific licensing requirements for assisted living. Families may be uncertain about the services provided for a loved one in any level of care.

For example other common names for assisted living include:

-

Residential care

-

Board and care

-

Congregate care

-

Adult care home

-

Adult group home

-

Alternative care facility

-

Sheltered housing

One of the challenges families confront when making a relocation decision on behalf of a relative with dementia is understanding the differences among a general assisted living community, a memory care assisted living and a nursing home. Assisted living models of all kinds have been on sharp rise in the last two decades a while the once phenomenal growth in nursing home beds has decreased by 7 %. Often their perception is more favorable towards assisted living as they may believe it is a more intimate, cost effective and homelike environment. Choosing the “correct” level of care may be difficult due to a number of factors. First, families may be in denial about their loved ones progressive care needs. Some assisted living is all inclusive in terms of fees and supports an aging in place model. Families, however can be surprised if there has not been full disclosure about the extent to which a residential care setting will go, to care for a demented person’s behaviors and physical care needs. Caregivers can experience disruption of multiple moves. They may believe a general assisted living facility (ALF) will be the final transition to be made by their loved one. Later, they may be informed that mom or dad needs a memory support program located elsewhere [48]. Then finally, at the last stage of the Alzheimer’s journey, when a loved one is at their frailest or most confused, families are confronted with yet another move to a skilled setting. Zimmerman and Fletcher [49] have documented that the emotional factors for families using a skilled or ALF alternative are more alike than different. Family guilt may be heightened, as well as exhaustion and financial duress increased, when multiple moves are required due to lack of initial awareness of levels of care. ALF families may spend more time in dialogue with physicians, monitoring finances and taking their loved one out socially. Caregivers using skilled settings for their loved ones spend an equal amount of caregiver energy monitoring changes in physical status and communicating with multiple levels of staff involved in their loved ones care. In both assisted living or skilled nursing settings, caregivers report using their time to advocate for quality of life and providing activity focused visits. Carers express feelings of relief related to decreased demands for physical care interventions with their loved ones. New roles become available. As some families who are frequent visitors network with other families; take an interest in those other families’ loved ones, and form meaningful relationships and alliances. More often however, families visit at their convenience, focus on their loved ones needs, interface only with their loved one and perhaps with staff and remain somewhat isolated in their roles. Guilt, grief, loneliness, relief and ambiguous mourning are often the sentiments expressed by family members who move the person with dementia to any level of care.

Discrete memory care settings have emerged since the late 1990s. Families using these settings may experience more understanding and feelings of assurance from staff specifically trained in dementia care. They may also have had pre-existing relationships with other families through support groups or Alzheimer’s Association programs and may be better educated about the disease process leading them to seek out these specialized care settings. Once the immediate physical care needs are addressed through placement, families may have attended to the legal, financial and end of life decisions. If not, placement will prompt these discussions. Some settings stress the availability and desirability of hospice as the next option in the Alzheimer’s course. But many families who are exhausted by decisions and transitions still may not be as prepared as desirable for the last set of decisions they may have to make for their loved one [50].

Hospitalization

They fall asleep in a world they know and wake up in a world of pink coats and green coats, bright lights and unfamiliar faces

Hospitalization can be a frightening time for both the person with dementia and their caregiver. Often it is not the Alzheimer’s symptoms that bring a person with dementia to the hospital. People with dementia can have many comorbid conditions that often result in hospitalization [51]. It has been documented that hospital staff in general are not educated about the special needs of people with dementia during hospitalization. Table 5 shows results of a small but recent study examining the preparedness of hospital staff to meet the special needs of the patient with dementia. As indicated in the table, even though the staff report that more than 32 % of their patients have dementia, the majority of staff have had no specific education about how to meet these special needs. As caregivers, it can be challenging to understand the complex and often chaotic world of the hospital. Staff may not recognize the persons’ dementia and then may not initiate contact to update information and communicate appropriately with caregivers in addition to the primary “patient”. This leaves families feeling uniformed and helpless.

There was no one around. I couldn’t even leave mom long enough to go to the bathroom.

Families may expect hospital staff to be knowledgeable about dementia and appropriate approaches toward care. The discrepancy between the perceptions of the family caregiver and the reality of hospital staff skills is clear. Consequently, hospitalization for the person with dementia, and their care partners is extremely stressful. While staff education is essential to shifting this paradigm, families can engage as advocates for their loved ones. Caregivers want to understand their role at the hospital. Most are the primary caregivers and feel responsible 24/7. So, now that their loved one is in the hospital: What is their role? There are many questions inherent to hospitalization. Families often wonder about when they are allowed to be present, about restraints, medication changes and about changes in the patients’ level of independence. They may not feel empowered to address questions or concerns with health care providers such as hospitalists or know ways to make hospitalization more successful. Caregivers are so focused on trying to get current medical information that they may be slow to ask questions about what kind of care of care they need to provide or coordinate when their loved one leaves the hospital [51]. Returning home can be an area of concern and stress on a family caregiver dependent upon the changes that the person with dementia experienced during hospitalization. Carers may question and worry about whether the hospitalization has moved them closer to needing nursing home care for their loved one. Hospitalization ideally may be an opportunity for families to gain greater insight onto their loved ones needs, current medical information and support for making short term and long term arrangements for care. as hospitals place greater emphasis on transitional care planning.

Family Participation in Dying Process

The demands of caregiving may intensify as people with dementia approach the end of life. In the year before the person’s death, 59 % of caregivers felt that they were “on duty” 24 h a day, and many felt that caregiving during this time was extremely stressful. One study of end of life care found that 72 % of family caregivers said that they experienced relief when the person with dementia died [52]. Consequently, preparing for this stage of the disease is essential. In a caregiving journey that can last 8–12 years, most carers are depleted in many realms by this stage of the disease. Preparing for death of a person with dementia is variable amongst caregiving families. Family members may be dealing with a loved one who has given consideration or made explicit plans about their end of life wishes. According to www.conversationproject.org, 60 % of people say that making sure that their family is not burdened by tough decisions is “extremely important”. Yet, 56 % have not communicated their end of life wishes [53]. Care partners of someone in the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease ideally make it a priority to have that difficult conversation while the person is still able to express their wishes. As the person declines, it can be a great comfort to the person with dementia and their care partners to know that their wishes regarding end of life care are clear and will be respected. Advance directives are the legal document that once signed and witnessed, express the details of what a person wants at the end of life. While forms can be free and are easily accessible online, families should have them reviewed by an elder law attorney. Unfortunately, many people miss the opportunity to know or understand the wishes of their loved one with dementia. There are still ways to prepare for end of life decisions. Caregivers can consider the things they know from the past about the person with dementia. How have they handled other illness? What have they said, possibly to or about others, during conversations about death or dying? It is important for the caregiver to find support, both personal and professional, during this stage of the disease.

Hospice

Hospice can be a positive option not only for the person with dementia, but also their caregivers. There are many cultural norms and beliefs surrounding the use of hospice care by dementia caregivers. Some families believe hospice equates to “giving up on” the person with dementia or hastening their death. Some may even equate the use of hospice as a death wish [54]. Other families believe, that because hospice is typically reserved for those with 6 months or less to live, it is not a viable option for their loved one with Alzheimer’s disease. It is important for caregivers to talk with healthcare providers about hospice even before the need becomes evident. Families engaged in a hospice program report many perceived advantages to the program [55]. Other families reflect that waiting until too near death may be a missed opportunity for the person with AD/related dementias to experience a dignified death. The hospice focus on palliative care can be a great relief for caregivers as they see their loved one more comfortable. Hospice also offers caregivers significant support through death preparedness and grief counseling. Many hospice programs offer unique services such as chaplaincy, music therapy, aromatherapy and pet therapy to aid in celebrating the dignity of the dying person with dementia.

Family as Advocates

Merriam-Webster defines an advocate as, one that supports or promotes the interest of another. Caregivers of a person with dementia are thrust into the role of advocate in so many ways during the entire course of the illness. At some stage people with dementia are no longer able to express their wishes. Caregivers, become the advocates to meet this need.

Advocacy on medical issues may start for the caregiver even before diagnosis. Caregivers are often helping the person with memory concerns manage existing chronic conditions and obtain an accurate diagnosis. This may require multiple long office visits and being persistent to get the attention of medical personnel. As the needs of the person with dementia change, caregivers will advocate for appropriate medications, living arrangements and services. Possibly the most important medical advocacy comes at the end of life when a caregiver needs to make sure that the person’s wishes are upheld and respected.

Socially, caregivers play a big role helping the person with dementia maintain relationships and navigate the outside world. Social isolation is a common report of caregivers. Friends and other family members may withdraw from contact due to a lack of understanding or discomfort [56]. Yet, social interaction can be very good for a person with dementia and so caregivers may have to advocate by educating and making friends feel more comfortable around the person with dementia. Additionally, it may not be apparent that a person has dementia simply by their appearance. Consequently, service staff at restaurants or grocery stores may not understand the behavior or social limitations of the person with dementia.

Political advocacy is essential to educating the regulators and policy makers about dementia and the needs of those with the disease [57]. Many organizations work at the local and federal levels to meet with politicians to gain financial support for research and services. Caregivers have a personal story to share with these law makers that can impact future care and finding a cure.

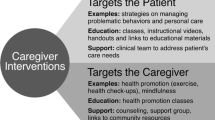

Reflections on Burden Versus Privilege of Caregiving

Caregivers of persons with dementia vary in their perceptions of burden versus privilege based on the many factors mentioned in this chapter. This includes long held views on reciprocity, ethnically influenced values, culturally accepted practices and the pre/post disease relationship to the affected individual. The ability to resolve, compartmentalize, integrate, and respond to, what may be a 20 year journey with a confusing disease process, may differ based on social, financial and spiritual resources available to caregivers. Many studies have shown that Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders’ caregivers, suffer from depression and other adverse physical and psychological repercussions. There have been encouraging studies on the effects of comprehensive support programs on depression in caregivers. A myriad of psychosocial and educational intervention programs (as will be explored in subsequent chapters), can support the primary caregiver and family members over the entire course of the disease in ways that ameliorate the potential negative effects of caregiving. Models include individual and family counseling available 24/7, enrollment and participation in research trials, socialization programs and support group participation. Programs pioneered by Alzheimer’s Associations and Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers across the United States, for affected individuals and their family members, have been shown to positively impact the excess burden associated with caregiving. Studies have shown that caregivers engaged in these interventions were significantly less depressed than those in the not so engaged in similar services,. These results suggest that enhancing long-term social support can have a significant impact on negative consequences of caregiving. Factors influencing caregiving experiences in the future include the availability of normalization and socialization opportunities for caregivers to share with their loved one, creative use of technology to support safety and societal acceptance of memory impaired persons. The social isolation and stigma experienced by caregivers even a decade ago, is being replaced with a more accepting attitude toward cognitive impairment. Normative experiences with neurological diseases are now shared among “Baby Boomers” and the availability of more person-centered and dignified care settings to care for the memory impaired, may remove some of the guilt associated with using long term care options.

It usually takes time and reflection for families, in the throes of physical caregiving, to integrate the emotional experience and accept the entirety of the caregiving experience as a privilege. When this acceptance occurs caregivers report positive feelings of re-engagement with a parent in a new and different way; a sense of fidelity toward a spouse or the ability to celebrate the newly found skills living in the moment with a memory impaired loved one. Families express gratitude for the strengths they were able to tap to take care of someone living with dementia and express pride in the lesson the situation served for future generations and younger members within the family. An indicator of this is the burgeoning literature written by caregivers about their experiences. The attitudes toward the caregiving experience are, as one would expect, largely influenced by pre-existing life views and life’s stories as well as the need family member have to repay, reward or resolve their prior familial relationship with the person with dementia. Caregiving remains rich investigative territory for gerontologists, social and health care researchers in decades to come as the “Boomers” experience and engage in the “Age of Dementia” and await long anticipated cure.

Discussion Questions

-

1.

Are family members better equipped to assume caregiving roles?

-

2.

Is caring for a person with dementia any different than any other caregiving role?

-

3.

What are some of the most promising resources caregivers can utilize to create an optimal quality of life caregiving experience?

References

Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310(6):575–6.

Alzheimer’s Association. Late stage caregiving: your role as a caregiver. 2014.

Gitlin LN, Schultz R. Family caregiving of older adults. In: Prohaska RT, Anderson LA, Binstock RH, editors. Public health for aging society. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014. p. 181–204.

Ory MG, Hoffmann RR, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist. 1999;39(2):177–86.

Rava S. Swimming solo: a daughters memoir of her parets, his parents and Alzheimer’s disease. Sewanee, TN: Plateau books; 2011.

Bouldin ED, Anderson E. Caregiving across the United States: caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia in 8 states and the District of Columbia. Data from 2009 and 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [Internet]. 2010

Meuser TM, Berg-Weger M, Chibnall JT, Harmon AC, Stowe JN. Assessment of readiness for mobility transition (ARMT): a tool for mobility transition counseling with older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32(4):484–507. doi:10.1177/0733464811425914.

Caregiving NAf, AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. Unpublished data analyzed under contract for the Alzheimer’s Association. 2009.

Fuller-Jonap F, Haley WE. Mental and physical health of male caregivers of a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Health. 1995;7(1):99–118.

Ohio department of aging. Whom does caregiving affect? 2009. Available from: http://aging.ohio.gov/resources/publications/Caregiver_Fact_Sheet_1-866.pdf

Robinson CA, Bottorff JL, Besut B, Oliffe JL, Tomlinson J. The male face of caregiving: a scoping review of men caring for a person with dementia. Am J Mens Health. 2014;8(5):409–26.

National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease and education center: intimacy sexuality and Alzheimer’s disease: a resource list. 2008. Available from: http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/intimacy-sexuality-and-alzheimers-disease-resource-list

Bookwala J, Schulz R. A comparison of primary stressors, secondary stressors, and depressive symptoms between caregiving husbands and wives: The caregiver health effects study. Psychology and aging. 2000;15:607–616.

Fisher GG, Franks MM, Plassman BL, Brown SL, Potter GG, Llewellyn D, et al. Caring for individuals with dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia: findings from the aging, demographics, and memory study. JAM Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):488–94.

Schumacher LAP, MacNeil R, Mobily K, Teague M, Butcher H. The leisure journey for sandwich generation caregivers. Ther Recreat J. 2012;46(1):42–60.

Hammer LB, Neal MB. Working sandwiched-generation caregivers: prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes. Psychol-Manag J. 2008;11(1):93–112.

Riley LD, Bowen CP. The sandwich generation: challenges and coping strategies of multigenerational families. Fam J. 2005;13(1):52–8.

Loomis LS, Booth A. Multigenerational caregiving and well-being. J Fam Issues. 1995;16(2):131–48.

Rubin R, White-Means S. Informal caregiving: dilemmas of sandwiched caregivers. J Fam Econ Iss. 2009;30(3):252–67.

National down syndrome society. 2014. Available at: http://www.ndss.org/

Chen H. Down syndrome: prognosis. Updated 8.2014. Medscape [Internet]. 2014.

Lancet Neurology (The). Strengthening connections between Down syndrome and AD. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(10):931.

Institute MMM. The Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. 2011.

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. 2014. pp. 30–58.

Hargrave R. Caregivers of African-American elderly with dementia: a review and analysis. Annals Long-term Care. 2006;14(10).

Haley WE, Gitlin LN, Wisniewwski SR, Mahoney DF, Coons DW, Winter L, et al. Well-being, appraisal, and coping in African-American and Caucasian dementia caregivers: findings from the REACH study. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(4):316–29.

Institue MLMM. Still out, still aging: the MetLife study of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender baby boomers. 2010.

Achenbaum WA. How boomers turned conventional wisdom on its head a historian’s view on how the future may judge a transitional generation. Metlife mature market institute. 2012.

Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Shen C, Panday RS, DeKosky ST. Alzheimer’s disease and mortality: a—year epidemiological study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(5):779–84.

Caregiving NAf, Schulz R, Cook T, Pittsburgh UCfSURDoPUo. Caregiving costs: declining health in the Alzheimer’s caregiver as dementia increases in the care recipient. 2011.

AgingCare.com. Thirty percent of caregivers die. 2014. Available from: http://www.agingcare.com/Discussions/Thirty-Percent-of-Caregivers-Die-Before-The-People-They-Care-For-Do-97626.htm

Mavarid M, Paola M, Spazzaumo L, Mastriforti R, Rinaldi P, Polidori C, et al. The caregiver burden inventory in evaluating the burden of caregivers of elderly demented patients: results from a multicenter study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;17(1):46–53.

Carr D, Duchek JM, Meuser TM, Morris JC. Older adult drivers with cognitive impairment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(6):680–7.

Carr DB, Ott BR. The older adult driver with cognitive impairment “it’s a very frustrating life”. JAMA. 2010;303(16):1632–41.

Kohm R, Surti GM. Management of behavioral problems in dementia. J Med Health. 2008;91(11):335–8.

Levy ML, Miller BL, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Craig A. Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(7):687–90.

Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, Whitlatch CJ. Caregiving as a dyadic process: perspectives from caregiver and receiver. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2002;57B(3):195–204.

Morris SE, Cuthbert BN. Research domain criteria: cognitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behavior. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14(2):29–37.

Boss P. Ambiguous loss: Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA.

Kind V. The caregiver’s path to compassionate decision making: making choices for those who can’t (Home Nursing Caring). Austin, TX: Greenleaf book group; 2010.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Kolcaba KY, Fisher EM. A holistic perspective on comfort care as an advance directive. Crit Care Nurs Q. 1996;18(4):66–76.

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer news: new statement to medical community demands a dignified diagnosis of dementia. 2009.

Robinson KM, Buchwalter KC, Reed D. Predictors of use of services among dementia caregivers. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27(2):126–40.

Pew Research Center. The return of the multi-generational family household. A social and demographic trends report. 2010.

Mollica RF. Coordinating services across the continuum of health, housing, and supportive services. J Aging Health. 2003;15:165–88.

Zarit SH, Kim K, Femia EE, Almeida DM, Savla J, Molenaar PCM. Effects of adult day care on daily stress of caregivers: a within-person approach. J Gerontol Ser B Psychologic Sci Soc Sci. 2011.

Kane RL, West JC. It shouldn’t be this way—the failure of long term care. Nashville, TN: Press V; 2005.

Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Fletcher S. The measurement and importance of quality in tomorrow’s assisted living. In: Golant S, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: a vision for the future. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008.

Span P. The new old age: caring and coping. Avoiding the call to hospice. 2009.

Silverstein NM, Maslow K. Improving hospital care for persons with dementia. New York: Springer; 2006.

Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE, Mahoney D, Allen RS, Zhang S, et al. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(20):1936–42.

Conversationproject.org. 2014.

Wilder HM, Oliver DP, Demiris G, Washington K. Informal hospice caregiving: the toll on quality of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2008;4(4):312–32.

Raleigh H, Robinson ED, Hoey J, Marol K, Jamison TM. Family care perceptions of hospice support. J Hosp Palliat Care Nurs. 2006;8(1):25–33.

Robinson J, Fortinsky R, Kleppinger A, Shugrue N, Porter M. A broader view of family caregiving: effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work, and social isolation. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2009;64B(6):788–98.

Alzheimer’s Association. Nearly 60 percent of people worldwide incorrectly believe that Alzheimer’s disease is a typical part of aging. Alzheimer’s News 2014 [Internet]. 2014.

SAGE. The issues—disability [cited 2014]. Available from: http://www.sageusa.org/issues/disability.cfm#sthash.veWCfUpO.dpufthere

Association NAPS. Policy and advocacy: elder financial exploitation.

Bookman A, Kimbrel D. Families and elder care in the twenty-first century. Future Child. 2011;21(2):117–40.

Bretcher C. Alzheimer’s Association, Saint Louis Chapter. Train the trainer manual. 2013.

Brookmeyer R, Corrada MM, Curriero FC, Kawas C. Survival following a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;59(11):1764–7.

Curry LA, Wetle T. Ethical considerations. In: Evashwick CJ, editor. The continuum of long term care. 3rd ed. Clinton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning; 2005. p. 279–92.