Abstract

Pictographic symbols are used on many kinds of maps because they are able to convey information efficiently. There is still little research on the factors that affect the comprehension of map symbols. In this paper, we analyze the semantic contents of map symbols designed by university students from different countries to study how (1) the concepts to be depicted and (2) the differences in the cultural backgrounds of designers affect the design of the symbols. The results suggest that cultural conventions strongly affect the design and interpretation of map symbols. For some concepts, it is difficult to design an intuitive symbol, even for a user group with a homogeneous cultural background, because of the broadness of the concept or the lack of a logical representation strategy for the concept. In practice, easily interpretable symbols can be achieved by involving a representative set of intended users in creating ideas for the symbols.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Pictographic symbols are commonly used in many different environments, such as tourist maps, cell phone and computer interfaces, automobile dashboards, traffic and safety signs, and way finding systems in public spaces. The use of pictographic symbols on maps has diversified as a result of improved screen resolutions, expanding use of maps, and the emergence of mobile applications.

The advantage of pictographic symbols on maps is that they are able to convey information without the necessity of a legend. However, the symbols need to be correctly interpreted by the user before this advantage can be claimed. The correct interpretation of map symbols must be ensured by asking the intended users of the symbols for their opinions (e.g. Kostelnick et al. 2008) or by conducting a comprehension test of the symbols (e.g. Akella 2009). While testing is a necessary phase of the symbol design process, effort should also be put into the improvement of the design phase so that resources are not wasted on designing and testing poor symbols. There is still little research within cartography on the factors that affect the comprehension of map symbols that could then guide the designer. We tackle this problem by studying how the concepts to be depicted and the differences in the cultural background of the users affect the design of the symbols.

In the next section, we present an overview of related work on the variables involved in the comprehension of pictographic symbols. We then present an analysis of map symbols designed by university students where the semantic contents of the symbols and the representation strategies used in the designs are analyzed to study the cultural effects and the design difficulties caused by the characteristics of the concepts to be depicted. Finally, the meaning of the results is discussed and conclusions are drawn.

2 Pictographic Symbols

The comprehension of symbols is commonly explained in the literature through the semiotic concept of a sign. Semiotics was introduced independently by Charles Sanders Peirce (1935) and Ferdinand de Saussure (1959). Peirce understood a sign as a triadic relation composed of the representamen (the symbol, the visual representation), the object (the referent that is represented by the symbol), and the interpretant (the mental representation of the object or the logic that connects the object and the symbol). De Saussure, who used the term semiology and worked especially on linguistic semiology, modeled a sign as a dyadic relationship between a signifier (the symbol) and a signified (the referent). Peirce’s model is perhaps the most suitable for reviewing the comprehension of symbols because it suggests that the interpretation depends on (1) the characteristics of the symbol itself, (2) the referent it represents, and (3) the person who is interpreting the symbol. The connections between the three are reviewed in this chapter with the help of related work on representation strategies for pictographic symbols and on the semantic qualities of pictographic symbols.

2.1 Representation Strategies for Pictographic Symbols

The design idea for a symbol is the concept(s) chosen for representing the referent. For example, the design idea for a referent such as health services can be a red cross. Peirce categorized signs on the basis of how the symbol is linked to its meaning (i.e. how the design idea represents the referent). Since Peirce, there have been multiple categorizations that commonly classify the symbols into: (1) those that represent the referent by depicting its visual characteristics, (2) those that are attached to the referent by a convention, and (3) those that represent the referent by depicting concepts that are semantically related to the referent (Forrest and Castner 1985; Purchase 1998). There has been criticism that it is difficult to divide real symbols into these discrete categories. Suggestions have been made that symbols should instead be placed on a continuum of iconicity, beginning from simple geometric shapes and ending with realistic and detailed pictures of real-world objects (MacEachren 1995).

Nakamura and Zeng-Treitler (2012) stated that, in practice, most referents are visualized with the help of concepts that are semantically related to the referent (i.e. through semantic association), but that the relationships between the related concept and the referent can be of various kinds. Therefore, they provided a more granular taxonomy of representation strategies and divided semantic associations into subclasses such as comparison, exemplification, semantic narrowing, physical or temporal decomposition, body language, metaphor, and contiguity. Contiguity was further divided into physical contiguity, container, source, use, cause or effect, tool, and object. Additionally, the symbols that represent the referent by arbitrary convention were divided into abstract, concrete, and transposed conventions by Nakamura and Zeng-Treitler (2012).

2.2 Semantic Quality of Pictographic Symbols

In addition to representation strategies, the relationships between the representation, the referent, and the interpreter can be examined through the semantic characteristics or qualities of the symbol. McDougall et al. (1999) introduced symbol characteristics such as concreteness, semantic distance, and familiarity. Concrete symbols depict real objects, materials, or people, whereas abstract symbols do not (McDougall et al. 1999). A symbol that is depicted by a geometric form, such as the symbol in Fig. 1a, is visually abstract, whereas the symbol in Fig. 1b is concrete because it depicts real objects (a snake and a staff). The semantic distance is the closeness of the concept that is depicted in the symbol to the referent that it represents (McDougall et al. 1999). The representation is semantically absolutely closest to the referent when the contents of the symbol depict the referent itself, which, however, is quite rare in practice. The representation is semantically farthest from the referent when the referent is represented through an arbitrary convention that cannot be reasoned without knowing the convention. For example, the semantic distance in all of the symbols in Fig. 1, except Fig. 1d, is long because it is impossible to reason the connection between the design idea and the referent if the symbol is not familiar from earlier experience. The familiarity of symbols is defined as the frequency with which the symbols are encountered and the familiarity of the connection between the symbol and the referent it represents (e.g. that a book is a well-known symbol for a library; Isherwood et al. 2007). The symbol in Fig. 1a can be considered more familiar than the symbol in Fig. 1c because it is encountered more often.

Semantic distance is stated to be the best predictor of symbol interpretability (Chan and Chan 2013), but the concreteness (Chan and Chan 2013) and the familiarity (Ben-Bassat and Shinar 2006; Isherwood et al. 2007; Chan and Chan 2013) of the symbols also have a strong effect on the speed and accuracy of the interpretation of a symbol. In addition, familiar symbols tend to be preferred by users (Oh et al. 2013). The familiarity of symbols in turn depends on the cultural background of the users (Lesch et al. 2009; Korpi and Ahonen-Rainio 2010; Blees and Mak 2012). Concreteness, semantic distance, and familiarity can be seen as factors that contribute to the overall quality of the design idea for a referent.

In addition to the efficiency and effectiveness of symbol interpretation, the subjective suitability (or acceptability) of the design idea for the referent also affects the usability of the pictographic symbols. This aspect of the quality of symbols can be recorded by asking the users to rate the suitability of different candidate symbols (Böcker 1996). For example, users may generally prefer one of two equally well-interpreted design ideas for a referent. The subjective suitability of the symbols depends on cultural differences, as symbols that are felt to be acceptable in one culture may even be offensive in another (Korpi and Ahonen-Rainio 2010).

3 Materials and Methods

We analyzed the design ideas applied by students when designing map symbols to study how the characteristics of the referent and the cultural background of the designer affect the representation of map symbols. The symbols that were analyzed originated from a symbol design task that was one of the assignments of an annually organized Master’s program course, “Visualization of Geographic Information.” The symbols were designed by 75 students in four years (2009 and 2011–2013). A little more than half of the students (40) were Finnish, whereas the rest (35) came from 17 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America (Austria, Bangladesh, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Ethiopia, France, Hungary, India, Iran, Nepal, Netherlands, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, and United Kingdom). The educational background of the students varied but the majority had majored in cartography or geoinformatics. The rest had an interest in cartography and some studies in the field. The task was to design pictographic symbols to represent eight given activity areas of regional planning. The areas varied slightly from year to year; in total, designs for ten areas of regional planning, as the referents, were covered: agriculture and forestry, industry, administrative services, health services, social services, transportation, cultural services, educational services, commercial services, and environmental care. The students were allowed to design manually by using pen and paper or to use the design software of their choice. The task was given after a lecture and classroom exercises on symbol design.

In the pre-analysis, the contents of the symbols were identified and categorized according to the individual concepts in the design and a combination of the concepts. For example, the contents of the symbol in Fig. 1d consist of a combination of a doctor and a (red) cross as well as two individual concepts, a doctor and a cross.

The actual analysis of the design ideas was conducted in four stages. First, the contents of the symbols were analyzed as the combination of concepts by using the measures that are commonly used in analyzing design ideas gathered with the stereotype production method. In the stereotype production method, a group of representative users is asked to draw a picture that best describes the referent (Ng et al. 2012). The most frequent design idea generated for the referent is known as the population stereotype, and the stereotype strength is the ratio of the most popular design idea to the total number of designs (Ng et al. 2012). We collected the stereotypes for each referent and measured the stereotype strength that expresses the agreement among the users (or designers in this case). Second, the individual concepts included in the designs were analyzed. We calculated the number of concepts needed to cover 50 and 75 % of the total number of designs for each referent. These measures can be used to describe the agreement among the users when several concepts are included in the designs. Third, the representation strategies of the most frequent design ideas applied by the students were analyzed according to the taxonomy of Nakamura and Zeng-Treitler (2012), introduced previously. This analysis can be used to study how the strategies used in representing the referents differ among the referents. Fourth, the differences in the design ideas between the Finnish and international groups of students were analyzed by comparing the stereotypes, stereotype strengths, and number of concepts needed to cover 50 and 75 % of the designs in order to study the effect of the cultural background.

4 Results

4.1 Combination of the Concepts and Individual Concepts Included in the Designs

The stereotype strengths for most of the referents remained between 20 and 40 % (Table 1). However, there were substantial differences between the referents in this respect. The strongest stereotype was a factory representing industry, as 80 % of the students implemented a single factory building in their designs. The weakest stereotype was the recycling arrows representing environmental care areas, with a 15 % share.

Stereotypical design ideas for the referents are shown in Fig. 2. Although the stereotype strengths remained low in the case of several referents, similar concepts were included in many designs. The stereotype was always the most common concept represented alone, but the same concept was frequently included in the designs together with other concepts as well. For example, a book depicted alone was the stereotype for educational services, with a share of 23 % of the symbols. However, in total, a book was included in 52 % of the symbols, together with other common concepts such as graduation hats, pens, and students. The conceptual broadness of the referents obviously tempted the students to include several concepts in their symbols. For this reason, we estimated the level of agreement on the design ideas of the symbols by calculating the number of concepts that were required to cover 50 and 75 % of the designs (Table 2). For example, a book was included in 52 % of the symbols for educational services and a book or a graduation hat was included in 77 % of them. Therefore, 50 % of the designs were reached with one concept, and 75 % were reached with two concepts.

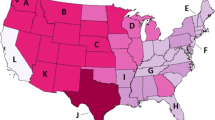

A symbol set designed by following the stereotypes for each referent. From the left in the top row are agriculture and forestry, industry, administrative services, health services, and social services. From the left in the bottom row are transportation, cultural services, educational services, commercial services, and environmental care

Generally, one or two concepts were needed to cover half of the designs, and a 75 % share was covered with two, three, or four concepts. The most difficult referent in this respect was administrative services, where six concepts were needed to cover 75 % of the designs. The concepts that were depicted were divided between colonnades (as a description of an administrative building), office symbols (e.g. forms, computers, and desks), and legal symbols (e.g. gavels, scales, and section signs). This suggests that administrative services is an abstract referent that is difficult to concretize consistently with a pictogram.

4.2 Representation Strategies Used in Depicting the Referents

The most commonly used strategies across referents were contiguities, such as tools and objects. Examples of tools that represent specific activities include a book that is used in studying, a shopping cart that is used in shopping, and a truck that is used in transporting goods (Table 1). Examples of objects are a family, which is a common customer of social services, and a tree and grain, as cultivated in agriculture and forestry. Additionally, characteristic buildings, as venues for the activity, were used, for example, in the cases of industry and cultural services. Buildings can be seen as one sort of container in the taxonomy of Nakamura and Zeng-Treitler (2012).

In the case of some of the referents, the students were able to make use of available conventions. A cross for health services and a recycling triangle for environmental care were examples of abstract conventions that were used. Theater masks for cultural services and a colonnade for administrative services can be seen as concrete conventions because they do depict real objects, but the objects have only historic links to the referent. Classic theater masks are not used in theater any more, and many administrative buildings today do not have colonnades on their façades.

In some cases, symbols were created by combining two or more strategies. For example, recycling arrows represent the concept of recycling, which is one part of the concept of environmental care. Therefore, the representation strategy actually combines two strategies: abstract convention and semantic narrowing. Semantic narrowing (i.e. visualizing an example of the whole concept) was frequently used in the case of many referents because the referents were broad. In addition to the strategies listed in Table 1, exemplification (i.e. the use of multiple examples) was commonly used in representing referents such as transportation and cultural services to cover a wider range of transportation vehicles or cultural attractions.

For some of the referents, the strategy used was consistent, whereas for others different strategies were used. For example, transportation was constantly depicted by transportation tools (i.e. vehicles) and only the choice of vehicle varied. For educational services, the strategy chosen by the designer varied. A book is a tool and a graduation hat is an object that represents graduation, which, in turn, is a sort of cause or effect of studying. Temporal decomposition (i.e. a snapshot of the teaching or studying situation) was another commonly used strategy for depicting educational services.

4.3 Effect of the Cultural Background

On average, a student produced 2.56 drawings classified as stereotypes (out of 8), with a standard deviation of 1.61. There was a significant difference in the scores for the groups of Finnish (M = 3.2, SD = 1.56) and international (M = 1.83, SD = 1.36) students: t(73) = 4.04, p < 0.00. This means that the contents generated by the two student groups differed significantly from each other. We performed the referent analysis of the two student groups separately in order to compare the symbols they designed. Table 3 shows that the stereotype strengths remained lower in the international group of students than in the group of Finnish students for most of the symbols. Additionally, the numbers of concepts needed for 50 and 75 % coverage were generally higher for the symbols designed by the international group of students than for those designed by the Finnish students. Only administrative services and environmental care needed more than one concept for 50 % coverage among the Finnish students. These results indicate that the design ideas varied more among the international group of students. It is clear that a more homogeneous cultural background produces more convergent design ideas. However, there seems to be variation between the referents in this respect. The ideas for environmental care—a relatively new concept with global interest—produced by the international group of students did not vary more than those produced by the Finnish students, whereas the ideas for cultural services varied greatly among the international group of students.

Cultural effects were also evident when a qualitative comparison of the stereotypes for the referents was performed. In the case of five of the referents (transportation, administrative, cultural, educational, and commercial services), different stereotypes were produced by the two student groups. A truck was a strong stereotype for transportation in the group of Finnish students, with a 58 % share, but the international students drew a bus more frequently. The stereotype for educational services among the Finnish students was a book, whereas among the international group of students the stereotype was a graduation hat. A colonnade was the stereotype for administrative services in the group of Finnish students, whereas the same design idea was the stereotype for cultural services in the international group of students.

5 Discussion

The results of the analysis of the contents of the symbols showed that there were remarkable differences between the symbols in terms of the level of agreement in their design ideas. In the case of some of the referents, the low stereotype strengths can be explained by the cultural differences between the designers, whereas some of the referents appeared to evoke various design ideas, regardless of the origin of the designer. This introduces two design challenges: (1) some referents are difficult to visualize in a pictographic symbol, and (2) some symbols have culturally dependent conventions that affect the interpretation. These two design challenges are discussed in the following sections.

5.1 Difficult Referents

Earlier studies suggest that there are remarkable differences in the level of difficulty of depiction between referents (Hicks et al. 2003). Our results suggest that there are differences in this respect even between the referents that lie at a seemingly similar conceptual level (i.e. between activity areas of regional planning). While this difference in the difficulty is a design constraint that should be realized and accepted by the symbol designer, the reasons why some referents are more difficult than others should be addressed as well. The referents used in our study were not obvious in evoking design ideas and thus introduced different semantic challenges for the design. We identified two reasons for why some referents are difficult to depict. Administrative services and environmental care seemed to be abstract concepts without easily visualizable and familiar related concepts that could concretize the referents. Cultural services seemed to be a concept that consists of several subclasses (i.e. different cultural services, such as music, theater, museums, etc.), and choosing a representative design idea for the whole concept was difficult. However, this problem only occurred among the international students because on Finnish maps theater masks are conventionally used to depict a wide range of cultural services, and therefore the Finnish students were able to count on this convention.

The results of the analysis of the representation strategies shed more light on the two kinds of difficult referents. The results show that the most common and thus “logical” strategies for representing a referent vary between the referents. One reason for the difficulty in visualizing a referent is that for some referents there is no logical or common strategy available. For example, for health services, there exists a familiar abstract convention, the healthcare cross, but designers find it difficult to find a convention, object, or tool to consistently represent administrative services. In the case of environmental care, there was an abstract convention to represent recycling, which, however, does not represent the whole concept of environmental care. Another reason for the difficulty in visualizing a referent is that some strategies seem to lead to specific design problems. In the case of cultural services and transportation, semantic narrowing was the logical strategy for representing the referent, but it led to too narrow of an understanding of the referent. For example, a note is easily interpreted as representing just music. Furthermore, the problems caused by the representation strategy used may be graphic rather than semantic. For example, attempts to depict a temporal decomposition of an office to represent administrative services and a teaching situation to represent educational services tended to lead to complex designs.

5.2 Culturally Dependent Symbols

Earlier studies revealed differences in the comprehension levels of pictographic symbols among users with different cultural backgrounds (e.g. Lesch et al. 2009; Blees and Mak 2012), which suggests that cultural background is an important factor affecting the interpretation of the symbols. Our results support this as the cultural differences seem to explain a substantial share of the variety in the design ideas created by the students. The differences in the design ideas between the two student groups were not limited to representation strategies seemingly counting on abstract or concrete conventions, but there were differences between the two student groups across the strategies. This suggests that conventions are continuously formed for visualizing a referent, and those conventions may not be easily predicted. For example, deciding to use a transportation vehicle for depicting the transportation domain does not depend on the cultural background of the designer, but the decision to use a truck instead of a bus is influenced by the frequency with which the designer has seen a truck used in the context of transportation. Therefore, the familiarity of the connection between the design idea and the referent seems to be an important semantic quality. Furthermore, there are differences in the design choices between the designer groups that may be based on preference considerations. These differences are likely to exist between two user groups from different cultural areas as well, but the preferences are difficult to notice by comprehension tests.

Guidelines for designing culturally independent symbols are presented in our earlier work (Korpi and Ahonen-Rainio 2010). One addition to the list of suggestions presented there is to include participatory methods in the design process. Participatory methods, such as the stereotype production method, rely on the assumption that symbols with design ideas produced by regular users “have a higher chance of being correctly interpreted by them” (Schröder and Ziefle 2008). In addition, the users are likely to produce design ideas that they prefer. Therefore, the stereotype production method seems to be a useful method for getting semantically high-quality design ideas in practice, because it takes into account all the semantic qualities that are appreciated by the users when drawing the suggestions for the symbols. The stereotype production method therefore helps to ensure the semantic quality of the symbol, even in the early stages of the design process. However, it is important that the participating sample users represent the intended users of the symbol set because an unrepresentative set of users may result in wrong design ideas, as was shown by the study.

6 Conclusions

We analyzed the contents of 600 symbols representing ten referents in order to study the variables involved in pictographic map symbol design and comprehension. We found out that cultural conventions define many of the design ideas the students use when designing symbols. This indicates that there are also differences between users when interpreting the symbols. It is difficult for designers to predict the cultural dependency of the symbols they design, because their cultural background affects the design choices more than expected.

The design challenges also depend on the referents and the representation strategies used. For some referents, the choice of a representative symbol is obvious, whereas for others it is difficult to design an intuitive symbol even when the user group is homogenous; this difficulty stems from the conceptual broadness or abstractness of a referent. These problems in turn may lead to the lack of a solid representation strategy. For some referents, designers naturally end up using a consistent representation strategy, but that strategy may produce further design challenges, such as visual complexity of the symbol.

One practical recommendation to achieve successful symbols for difficult concepts is to involve the users in creating the ideas for the symbols. However, it is critical that the users involved are representative of the intended user population of the symbols. In particular, the cultural background strongly affects the familiarity and preferences of different design ideas.

Finally, the research methods used in the study were found to be useful in studying the variables involved in the comprehension of pictographic symbols. Measuring the stereotype strengths and calculating the number of concepts needed to cover 50 and 75 % of the total number of designs gave information on the agreement between designers in choosing design ideas for symbols. Analyzing the representation strategies used by the designers and comparing the designs by homogenous and heterogenous groups of designers to each other gave information on the reasons for differences in the levels of agreement between the referents.

References

Akella MK (2009) First responders and crisis map symbols: clarifying communication. Cartography Geogr Inf Sci 36(1):19–28

Ben-Bassat T, Shinar D (2006) Ergonomic guidelines for traffic sign design increase sign comprehension. Hum Factors 48(1):182–195

Blees GJ, Mak WM (2012) Comprehension of disaster pictorials across cultures. J Multilingual Multicultural Dev 33(7):699–716

Böcker M (1996) A multiple index approach for the evaluation of pictograms and icons. Comput Stand Interfaces 18:107–115

Chan AH, Chan KW (2013) Effects of prospective-user factors and sign design features on guessability of pharmaceutical pictograms. Patient Educ Couns 90:268–275

de Saussure F (1959) Course in general linguistics. Philosophical Library, New York

Forrest D, Castner HW (1985) The design and perception of point symbols for tourist maps. Cartographic J 22(1):11–19

Hicks KE, Bell JL, Wogalter MS (2003) On the prediction of pictorial comprehension. In: Proceedings of the human factors and ergonomics society annual meeting (1735–1739), Denver, Co.

Isherwood SJ, McDougall SJ, Curry MB (2007) Icon identification in context: the changing role of icon characteristics with user experience. Hum Factors 49(3):465–476

Korpi J, Ahonen-Rainio P (2010) Cultural constraints in the design of pictographic symbols. Cartographic J 47(4):351–359

Kostelnick JC, Dobson JE, Egbert SL, Dunbar MD (2008) Cartographic symbols for humanitarian demining. Cartographic J 45(1):18–31

Lesch M, Rau P-LP, Zhao Z, Liu C (2009) A cross-cultural comparison of perceived hazard in response to warning components and configurations: US vs. China. Int J Ind Ergon 40:953–961

MacEachren AM (1995) How maps work: representation, visualization, and design. The Guilford Press, New York

McDougall SJ, Curry MB, de Bruijn O (1999) Measuring symbol and icon characteristics: norms for concreteness, complexity, meaningfulness, familiarity, and semantic distance for 239 symbols. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput 31(3):487–519

Nakamura C, Zeng-Treitler Q (2012) A taxonomy of representation strategies in iconic communication. Int J Hum Comput Stud 70:535–551

Ng AW, Siu KW, Chan CC (2012) The effects of user factors and symbol referents on public symbol design using the stereotype production method. Appl Ergon 43:230–238

Oh K, Rogoff A, Smith-Jackson T (2013) The effects of sign design features on bicycle pictorial symbols for bicycling facility signs. Appl Ergon 44:990–995

Peirce CS (1935) Collected papers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, CA

Purchase H (1998) Defining multimedia. IEEE Multimedia 5(1):8–15

Schröder S, Ziefle M (2008) Making a completely icon-based menu in mobile devices to become true: a user-centered design approach for its development. In: Proceedings of the 10th international conference on human-computer interaction with mobile devices and services, pp 137–146. ACM, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Korpi, J., Ahonen-Rainio, P. (2015). Effect of Cultural Differences and Referent Characteristics on the Design of Pictographic Map Symbols. In: Robbi Sluter, C., Madureira Cruz, C., Leal de Menezes, P. (eds) Cartography - Maps Connecting the World. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17738-0_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17738-0_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-17737-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-17738-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)