Abstract

Introduction: Sexual violence is a pervasive, yet, until recently, largely ignored violation of women’s human rights in most countries. It occurs across socioeconomic and demographic spectrums and is frequently unreported by victims. Sexual violence is associated with negative physical, sexual, and reproductive health effects and, as importantly, it is linked to profound long-term mental health consequences. The reach of violence against women has been felt by women across Portugal and around the world. Violence against women has been documented for decades as a legal and social justice problem, but as addressed in this chapter, it is also a substantial mental health concern.

Main Body: The main aim of this chapter was to understand the frequency of experiencing sexual victimization in Portuguese women, how it affected their well-being/sense of coherence (SOC) as well as understanding the associations between sexual victimization and alcohol use. A convenience sample of 182 participants was collected among Portuguese women. The instrument used was a self-reported questionnaire developed by Krahé and Berger (2013). From the total sample, 24.2 % of women were victims of aggression at least once. Results suggested associations between sexual victimization, the age of first sexual intercourse, the number of partners, and alcohol use associated with sexual intercourse. Furthermore, victims reported significantly less SOC than non-victims.

Discussion: Although the study uses a small sample, results strongly suggested an association between sexual victimization and low SOC, early onset of sexual intercourse, number of partners, and alcohol use, although the direction of this causality is still to be established. Nonetheless, these findings demonstrate the relevance of studies in this domain and help understanding the role of psychology in this working field, enabling the elaboration of guidelines in terms of prevention and therapeutic intervention.

Implications: Though representing a minority, women who reported having been subjected to aggression in Portugal should be addressed. Women victims are subjected to physical, psychological, and/or sexual abuse at home by a relative, such as a partner, and in some circumstances by their brothers or parents. The factors associated with violence in Portugal are (a) having a low-economic status, (b) lacking of awareness about women’s rights, (c) lacking education, (d) false beliefs, (e) imbalanced empowerment issues between men and women, (f) male-dominant social structure, and (g) lacking support from the government. Support to victims, besides changing a whole culture that allows any violence upon others, must include universal and selective programs that allow women to build social and personal competences, preventing early sexual onset and potential risk situations associated with sexual intercourse (several partners and alcohol use during sexual intercourse), no matter if this potential risk situation means a personal option for risk behaviors or if it means an additional violence and abuse or an additional vulnerability. Support that helps women rebuilding and recovering their lives after violence should be a part of the intervention strategy, including counseling, relocation, financial support, and employment. To do intervention in victimized women and provide them medical as well as judicial and legal support, new plans and interventional maps should be made within the society in collaboration with health team members, religious and societal leaders, NGOs, police department, and people from other similar groups. Such a strategic intervention should be implemented.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Violence against women is a significant public health problem that has both short- and long-term physical and mental health consequences for women and their families (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013). Sexual violence is a pervasive, yet, until recently, largely ignored violation of women’s human rights in most countries (Kohsin Wang & Rowley, 2007; WHO, 2005, 2013). The United Nations define violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” and identify the same characteristics and consequences for such behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner (WHO, 2013, p. 31).

Sexual violence is any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any persons regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part, or object (Jewkes, Sen, & García-Moreno, 2002; WHO, 2013). In this study, sexual violence is defined as behavior carried out with the intent or result of making another person engage in sexual activity or sexual communication despite his or her unwillingness to do so (Krahé et al., 2014).

Worldwide, more than one-third (35 %) of all women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical, psychological, and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner. Globally, 38 % of all murders of women are committed by intimate partners (WHO, 2013). In Portugal, 38 % of women have experienced physical, psychological, and/or sexual violence since the age of 18 (Lisboa, 2008; Women Against Violence Europe, 2013). Portuguese criminal statistics indicate that there were 33,707 crimes of domestic violence in 2011, of which 27,507 of the victims were women. In 62 % of the cases, the perpetrator was a current partner and in 20.4 % a former partner (Women Against Violence Europe, 2013).

Violence occurs across socioeconomic and demographic spectrums and is frequently unreported by victims (Rennison, 2002; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Sexual violence is associated with negative physical, sexual, and reproductive health effects and, as importantly, it is linked to profound long-term mental health consequences (Astbury & Jewkes, 2011; Jewkes et al., 2002). According to WHO (2013), the risk factors for being a victim of intimate partner and sexual violence include low education, witnessing violence between parents, exposure to abuse during childhood and to attitudes of acceptance towards violence and gender inequality; the risk factors for being a perpetrator include low education, exposure to child maltreatment or witnessing violence within the family, harmful use of alcohol, and attitudes of acceptance towards violence and gender inequality.

Regarding health consequences, violence against women can have fatal results so far as homicide or suicide (Astbury & Jewkes, 2011; Jewkes et al., 2002). It can lead to injuries: 42 % of women who experienced violence inflicted by intimate partner reported injury (WHO, 2013).

Intimate partner violence and sexual violence can lead to unintended pregnancies, induced abortions, gynecological problems, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. The WHO-2013 analysis found that women who had been physically or sexually abused were 1.5 times more likely to have a sexually transmitted infection, including HIV, compared to women who have not experienced partner violence. They are also twice as likely to have an abortion (WHO, 2013).

These forms of violence can lead to depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleeping difficulties, eating disorders, emotional distress, and suicide attempts. The same study found that women who have experienced intimate partner violence were almost twice as likely to experience depression and drinking problems. The rate was even higher for women who had experienced non-partner sexual violence (WHO, 2013).

Health effects can also include headaches, back pain, abdominal pain, fibromyalgia, gastrointestinal disorders, limited mobility, and poor overall health (WHO, 2013).

According to several authors (Eriksson, Lindström, & Lilja, 2007; Rivera, López, Ramos, & Moreno, 2012), the possibility of coping with negative events without major damages in terms of well-being and personal health is often assessed through the sense of coherence (Antonovsky, 1987, 1993), which is considered a very comprehensive construct related to perceived understanding, to perceived management skills, and to perceived meaning of events.

The reach of violence against women has been felt by women across Portugal and around the world. Violence against women has been documented for decades as a legal and social justice problem, but as addressed in this chapter, it is also a substantial mental health concern. There are not many studies on this specific in Portugal. Therefore, the main aim of this chapter was to understand the frequency of experiencing sexual victimization in Portuguese women, how it affected their well-being, and understanding the associations between sexual victimization, sexual behavior, alcohol use, and sense of coherence.

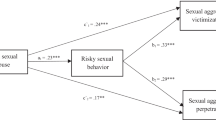

Youth Sexual Aggression and Victimization (YSAV) is a project cofinanced by the European Union in the framework of the Health Programme to address the issue of sexual aggression and victimization among young people. The project aims to build a multidisciplinary network of European experts in various member states, bringing together the knowledge on youth sexual aggression and victimization in a state-of-the-art database, developing a more harmonized way of measuring these issues and providing recommendations for strategic action to address the problem of youth sexual aggression under different circumstances in different EU member states (namely in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, and Spain). Portugal is part of this group since 2010 (http://ysav.rutgerswpf.org/project-partners).

Methodology of Research

Sample of Research

A national convenience sample of 182 participants was collected through an online questionnaire among Portuguese women in 2012. Only young people 18 years old or older participated. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. The majority of women are of Portuguese nationality (98.4 %), university students (74.7 %), and the mean age was 23.3 years (SD = 3.08). Each person could participate only once and completing the questionnaire lasted between 20 and 30 min.

The study had the approval of a scientific committee, the National Ethics Committee (by the Hospital Santa Maria), and the Portuguese Commission for Data Protection and followed strictly all the guidelines for human rights protection.

Instrument and Procedures

The instrument used was a self-reported questionnaire developed by the YSAV Group and Krahé and Berger (2013) which aimed to assess unwanted sexual experiences among young people. The questionnaire covers a wide range of questions, issues that relate to sociodemographic characteristics (age, nationality), victimization (Yes/No), sexual and risk behavior (Age of first sexual intercourse, number of partners with whom had sexual intercourse, having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol—Yes/No), and selected items from the sense of coherence scale (SOC-29; Antonovsky, 1987, 1993; SOC-13; translated and adapted by Rivera et al., 2012). A reduced SOC scale was used (13 items) and the original 1-to-7-point Likert-type scale was narrowed, combining the ratings 5, 6, and 7 together, computing a new “5” rating and labelling it to “very often to always.”

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 22 for Windows). Descriptive statistics including frequencies, means, and standard deviations was performed to give general descriptions of the data.

ANOVA was performed to examine differences in age of first sexual intercourse, number of partners with which participants had sexual intercourse, and sense of coherence scores, for the subgroups that mentioned having been/not having been victims. Having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol was compared between the victims/not victims subgroups using the Chi-square (χ 2) tests and adjusted residuals. The level for statistical significance was set at p < .05. Only significant results were discussed.

Findings

From the total sample, 24.2 % women were victims of aggression at least once.

Considering the whole sample, participants indicated that they had had their first sexual intercourse at a mean age of 17 years old, the mean number of partners with whom they had sexual intercourse was 3.41 (SD = 4.22), and the majority reported not having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol (72.3 %).

A significant variation was found between having been/not having been victim of aggression in terms of number of partners with whom they had sexual intercourse (F (1, 127) = 12.617, p < 0.001) and in relation to having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol (χ 2 (1) = 4.432; p < .05). The subgroup “victims” mentioned higher number of partners with whom they had sexual intercourse (M = 5.44; SD = 6.72) than the “not victims” subgroup (M = 2.62; SD = 2.33). On the other hand, the “not victims” subgroup indicated more frequently having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol (87.7 %) than the “victims” subgroup (71.0 %) (see Table 11.1).

The distribution of each item of the sense of coherence scale is shown in Table 11.2. The mean total score in relation to sense of coherence was 49.30 (SD = 12.51): those in the “not victims” subgroup showing significantly more sense of coherence (M = 53.84, SD = 13.88) than those in the “victims” subgroup [(M = 47.54, SD = 11.56 (F (1, 109) = 5.923, p = 0.05)].

Discussion

Our findings regarding prevalence of victimization (28.2 %) are consistent with findings of other countries that administered the same study. Between 20.4 % (Belgium) and 52.2 % (Netherlands) women reported at least one form of victimization. The lowest rate was found in Lithuania (19.7 %) and the highest rate was found in the Netherlands (52.2 %) (Krahé et al., 2014).

According to Krahé, Berger, Vanwesenbeeck et al. (under review, 2015), victimization rates were negatively correlated with sexual assertiveness and positively correlated with alcohol use in sexual encounters. National (Portuguese) findings are somehow different but discrepancies must be addressed with caution since the national sample is small, and most discrepancies may indeed refer to very specific national features. The national results showed that women in the “not victim” subgroup indicated having had sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol more often than those in the “victims” subgroup. This is perhaps explained by the fact that most women are university students and they have a high education which is considered as a protective factor according to other studies (WHO, 2013). On the other hand, the women in the “victims” subgroup reported less sense of coherence and a higher number of partners with whom they had sexual intercourse, in comparison to the women in the “non-victims” subgroup, meaning most probably that coherence is negatively related to issues like number of partners, which consequently may be considered a risk behavior.

Although the study is based on a small sample, results suggested strongly an association between sexual victimization and a low SOC, early onset of sexual intercourse, number of partners, and alcohol use, although the direction of this causality is still to be established. This research is also somehow limited in terms of the ability to generalize our findings to Portuguese women. However, they do provide a starting point for future studies with larger number of women.

Support to victims, besides changing a whole culture that allows violence upon others, must include universal and selective programs that allow women to build social and personal competences, preventing early sexual onset, and potential risk situations associated with sexual intercourse (several partners and alcohol use during sexual intercourse).

Interventions are needed for this group, as well as for those victims of physical, psychological, and/or sexual aggression, to prevent a range of physical and mental chronic and acute health consequences.

Future research is necessary to assess short- and long-term mental and physical health consequences of intimate partner violence by type and timing, as well as the health care costs of such violence.

For many women victims, contact with primary care providers may be the only opportunity for an effective intervention, because battering men are often very controlling. By asking about intimate violence in this setting, health care providers can support victims, validate their concerns, and provide them with needed community and medical referrals and more appropriate health care. Asking about intimate violence can lead to earlier interventions to reduce violence in the home or to help women safely leave abusive relationships, provided that clinicians are supportive of their patients’ emotional and financial needs and their need to work through difficult decisions in their own time. Early and effective interventions, both within the hospital/clinic and in the larger community, are needed to reduce the negative health consequences of intimate partner violence and to reduce society’s tolerance of nonfatal violence against women.

These findings demonstrate the relevance of studies in this domain and helped understanding the role of psychology in this working field and producing guidelines in terms of prevention and therapeutic interventions.

Implications

Gender-based aggression is still prevalent in Portugal at an alarming rate. Survivors experience diverse negative impacts of physical, sexual, and psychological aggression; there is no list of typical “symptoms” they should exhibit. What is shared is that such impacts are profound, affecting the physical and mental health of victims/survivors and their interpersonal relationships with family, friends, partners, colleagues, and so on. More than this, the impacts of aggression go beyond the individual, to have a collective impact on the social well-being (Sullivan, McPartland, Price, & Cruza-Guet, 2013; Women Against Violence Europe, 2013).

The factors associated with violence in Portugal are having a low-economic status, lacking of awareness about women’s rights, lacking education, false beliefs, imbalanced empowerment issues between men and women, male dominant social structure, and lacking support from the government (Lisboa, 2008). Support that helps women rebuilding and recovering their lives after violence should be a part of the intervention strategy, including counseling, relocation, financial support, and employment. To perform an intervention with victimized women and provide them medical as well as judicial and legal support, new plans and interventional maps should be made within the society in collaboration with health team members, religious and societal leaders, NGOs, police department, and people from other similar groups. Such a strategic intervention should be implemented (Lisboa, 2008; Women Against Violence Europe, 2013).

More resources are needed to strengthen the prevention of intimate partner and sexual violence, including primary prevention, i.e., stopping it from happening in the first place.

Regarding prevention, there is some evidence from some countries that school-based programs to prevent violence within dating relationships have shown effectiveness. Several other primary prevention strategies—those that combine microfinance with gender equality training; that promote communication and relationship skills within couples and communities; that reduce access to and harmful use of alcohol; and that change cultural gender norms—have shown some promise but need to be evaluated further (Capaldi & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2012; WHO, 2013).

To achieve lasting change, it is important to enact legislation and develop policies that (a) address discrimination against women; (b) promote gender equality; (c) support women; and (d) help to move towards more peaceful cultural norms.

An appropriate response from the health sector can play an important role in the prevention of violence. Sensitization and education of health and other service providers are therefore another important strategy. To address fully the consequences of violence and the needs of victims/survivors requires a multi-sectorial response (Capaldi & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2012; WHO, 2013). Some strategies that can enhance this multi-sectorial response are developing technical guidance for evidence-based intimate partner and sexual violence victims since it may contribute to strengthen the health sector’s response to such violence. Another is disseminating information and supporting national efforts that focus on women’s rights and the prevention of violence against women through sex education at school context, preferably in collaboration with international agencies and organizations that aim to reduce/eliminate violence. Violence and gender-based aggression are substantial mental health concerns, and they require a multi-sectorial response in order for both intervention and prevention to be successful.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unravelling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36(6), 725–733.

Astbury, J., & Jewkes, R. (2011). Sexual violence: A priority research area for women’s mental health. In R. Parker & M. Sommer (Eds.), Routledge handbook of global public health. New York: Routledge.

Capaldi, D., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2012). Informing intimate partner violence prevention efforts: Dyadic, developmental, and contextual considerations. Prevention Science, 13(4), 323–328. doi:10.1007/s11121-012-0309-y.

Eriksson, M., Lindström, B., & Lilja, J. (2007). A sense of coherence and health. Salutogenesis in a societal context: Åland, a special case. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 61(8), 684–688. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.047498.

Jewkes, R., Sen, P., & García-Moreno, C. (2002). Sexual violence. In E. G. Krug et al. (Eds.), World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.

Kohsin Wang, S., & Rowley, E. (2007). Rape: How women, the community and the health sector respond. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation/Sexual Violence Research Initiative.

Krahé, B., & Berger, A. (2013). Men and women as perpetrators and victims of sexual aggression in heterosexual and same-sex encounters: A study of first-year college students in Germany. Aggressive Behavior, 39, 391–404. doi:10.1002/ab.21482.

Krahé, B., Berger, A., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Bianchi, G., Chliaoutakis, J., Fernández-Fuertes, A., Fuertes,A, Matos,M.G., Hadjigeorgiou,E., Haller, B., Hellemans,S., Izdebski,Z., Kouta,C., Meijnckens, D., Murauskiene, L., Papadakaki, M., Ramiro, L., Reis, M., Symons, S., Tomaszewska, P., Vicario-Molina, I., & Zygadlo, A. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of youth sexual aggression and victimization in 10 European countries: A multilevel analysis. Culture, Health, and Sexuality. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.989265.

Lisboa, M. (2008). Gender violence in Portugal—A national survey of violence against women and men. [SociNova/CesNova, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa]: The Summary of Results is available at [http://sgdatabase.unwomen.org/uploads/Portugal%20-%20Gender%20Violence%20-%20National%20Survey%20Results.pdf].

Rennison, C. (2002). Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to police and medical attention, 1992–2000. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved April 26, 2013, from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsarp00.pdf. Accessed%2026/04/2013

Rivera, F., López, A., Ramos, P., & Moreno, C. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-29) in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 4, 11–39.

Sullivan, T., McPartland, T., Price, C., & Cruza-Guet, M. (2013). Relationship self-efficacy protects against mental health problems among women in bidirectionally aggressive intimate relationships with men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 641–647.

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2006). Extent, nature and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

World Health Organization. (2005). WHO Multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Women Against Violence Europe. (2013). Country Report 2012: Violence against women and migrant and minority women, Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Response

Response

Another day…

Day in, day out, and the anguish lingers, afraid of breathing, thinking and even speaking…

Day in, day out, and it’s the exact same day; no changes, no beginnings…

Day in, day out, and one’s senses are offered more excuses, rejected by a sore soul, hunted, perspiring solitude and dejection… “It’s harder for me than for you, trust me”, you say to this beaten down body already used to the pain. That body, indeed the only one that keeps crawling after each “fall”, getting back to the automatic state to which I’m confined, while the memories, those won’t cease, cannot cease and shall not forgive.

Day in, day out, and I can’t find any path to follow, fear reigns and is king: I hear the steps on the stairs, a quiet key in the lock, a door that unlocks, a quick smile that introduces the typical finale: questioning, accusations, screaming, pain and more pain… flesh twisting, a soul being torn down. And close by, closer than it should, as senses endlessly recall… hospital lights, the smell of ether, the crying of offspring, and disillusionment …deeply embedded in me.

Day in, day out, and I’m tired, exhausted. Enough torture, where are my little girl’s dreams: marriage and a “happily-ever-after” future? Where are my children, and their long lost smiles? Where is the love, the respect, the taking care of each other? This love smothers and tortures, annihilates hope and compromises the future… No, I dismiss this kind of love! No prior notice, that clear and simple.

Day in, day out,…but one of these days…it’ll be the day to stop… …

Anonymous

26 July 2013

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reis, M., Ramiro, L., de Matos, M.G. (2015). Impact of Gender-Based Aggression on Women’s Mental Health in Portugal. In: Khanlou, N., Pilkington, F. (eds) Women's Mental Health. Advances in Mental Health and Addiction. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17326-9_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17326-9_11

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-17325-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-17326-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)