Abstract

Violence against women, especially intimate physical violence, is widely recognized as a public health and a human rights issue. However, most studies on this subject have focused on women’s reports. This chapter examines men’s attitudes toward wife beating using the 2011 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, and compares never-married and currently married men’s responses to a five-scenario question for which men believe that wife beating would be justified. The results from bivariate analysis show that married men were more likely than never-married men to agree with the statements that wife beating is justified if the “wife goes out without telling her husband,” “neglects the children,” “argues with husband,” “refuses to have sex with the husband,” and “burns food.” However, these differences were statistically significant in logistic regression models only for refusal to have sex with the husband and burning food, for which married men appeared less likely to agree with wife beating than never-married men. Important regional differences are found with residents of Addis Ababa being the least likely to agree with wife beating followed by those in the Oromia region, whereas Somali and S.N.N.P. residents were significantly more likely to agree with wife beating statements. The effects of other socio-demographic variables are also discussed, including the policy implications and predictions for men’s attitudinal change in Ethiopia.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background

According to the 2013 Population Reference Bureau (PRB) report, Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, with 89.2 million inhabitants (PRB 2013). It is a multinational (multilingual) society with about 80 ethno-national groups; the main four groups are Oromo (34.5 %), Amhara (26.9 %), Somali (6.2 %), and Tigray (6.1 %) (CIA 2008). Consequently, Ethiopia is a multicultural society with diverse languages, customs, and religions. Its 11 federal regions are mainly based on the ethno-national groups inhabiting them: Oromia region (home of Oromos), Amhara regions (home of Amharas), Somali region (home of Somalis), and so on. It is also a multireligious society; the main three are Orthodox Christian (43.5 %), Islam (33.9 %), and Protestant (18.6 %) (CIA 2008).

A common denominator to this diverse cultural, linguistic, and religious composition of Ethiopia is that gender relations are not all equitable and many women suffer from various forms of partner violence in all settings. In a March 27, 2013, blog, Emnet Assefa wrote, “Everyone knows the presence of domestic abuse against women in Ethiopia; unfortunately no one knows how bad it is” (Assefa 2013). The Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women, sponsored by the World Health Organization and conducted between 2000 and 2003, showed that nearly half (49 %) of ever-partnered women in Ethiopia have experienced physical violence by a partner at some point in their lives; 59 % reported sexual violence and 71 % reported having experienced either one or both of these two types of abuse (World Health Organization 2005).

Further, qualitative studies conducted in Ethiopia found evidence of intimate partner violence. For example, a study in Northwest Ethiopia based on data from focus groups among women showed that “[t]he normative expectation that conflicts are inevitable in marriage makes it difficult for society to reject violence” (Yigzaw et al. 2010: 39). More recently, researchers have considered both men’s and women’s views of intimate partner violence in some parts of Ethiopia. A 2012 qualitative study in West Ethiopia in which 55 men and 60 women participated in focus group discussions revealed that most subjects perceived intimate partner violence to be widely accepted in the community, particularly in the case of infidelity (Abeya et al. 2012).

Quantitative research on men’s attitudes and the socio-demographic factors of their gendered behaviors toward women is very limited. One important work in this regard is the 2004 article published in the African Journal of Reproductive Health. In this comparative study of seven African countries based on Demographic and Health Survey data collected between 1999 and 2001, Rani and colleagues found that Ethiopian men were more likely to justify wife beating than their counterparts in five other countries with comparable data (Rani et al. 2004). Yet, because of its focus on comparative perspectives, no in-depth analysis of cultural norms embedded in regional differences of gender roles was examined.

In this chapter, we examine men’s attitudes toward wife beating, a physical abuse that is usually associated with greater harms. Studies conducted elsewhere show that spousal violence adversely affects the health and well-being of women. A study in urban slums in Bangladesh revealed that more than three-quarters of physically violated women suffered injuries; more than 80 % of sexually violated women complained of pelvic pain and more than 50 % had reproductive tract infections (Salam et al. 2006). Similar results were found in Egypt, where ever-beaten women were more likely to report health problems necessitating medical attention (Diop-Sidibe et al. 2006).

In this study, we provide national estimates of Ethiopian men’s views of wife beating using the most recent Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (2011 EDHS). Previous research in Africa has identified certain socio-demographic variables that increase or otherwise decrease men’s acceptance of wife beating. Among these, education has been associated with reduced likelihood of acceptance of wife beating in Ethiopia, as well as in Benin, Mali, Rwanda, and Uganda (Rani et al. 2004). Men who have higher educational attainment are more amenable to negotiation when it comes to marital conflicts and spousal relations. Therefore, we expect educated men to be less inclined to approving of wife beating in contemporary Ethiopia.

Age was also found to be negatively linked to men’s acceptance of wife beating in an earlier study in Ethiopia (Rani et al. 2004). It seems like older men are more tolerant to wife beating than younger men. Thus, we expect similar findings in the present study. Nonetheless, our study goes beyond previous research by including both the type of place of residence (rural/urban) and the region of residence in the analysis to capture differences in local gender norms. Due to exposure to various cultures in cities, we expect urban residents to be less supportive of wife beating than their rural counterparts. In the same way, we expect men who listen to radio, watch TV, and read newspapers to be less inclined to agreeing with statements that wife beating is justifiable.

In some parts of Ethiopia, including the capital, Addis Ababa, the Orthodox Church is the main religious denomination. In that church, Mary, mother of Jesus, is considered as one of the main messengers of God (Jesus). Followers of the Ethiopian Orthodox believe that Saint Mary has a supernatural power to convince Jesus. They call her “amalaj” which means negotiator (with Jesus) in Amharic language. Her picture exists in nearly every Orthodox believer’s home and most of them pray mainly to her (not to Jesus). As such, we expect members of the Ethiopian Orthodox church to be less supportive of wife beating than their counterparts in other religious denominations, including those without religion.

Methods

Data

This study is based on the 2011 EDHS. The survey was carried out over a 5-month period from December 27, 2010, to June 3, 2011, by the Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency (CSA) under the auspices of the Ministry of Health. The 2011 EDHS was a nationally representative survey with a sample of 17,018 occupied households of which 16,702 were interviewed, representing a household response rate of 98.1 %. All women aged 15–49 and all men aged 15–59 in these households were selected for interview. A total of 15,908 men were selected and 14,110 were interviewed, representing a response rate of 88.7 % (Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International 2012: 11–12). This study is limited to the 13,192 men who were married or never married at the time of the survey.

Dependent Variables

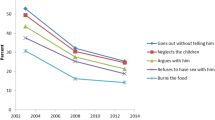

In addition to regular demographic and health questions, the 2011 EDHS included a module measuring the number of situations in which the respondent considers wife beating justifiable. More specifically, survey participants were asked to say whether they agree or not that a husband is justified in beating his wife in the following circumstances: if the wife (1) goes out without telling the husband; (2) neglects the children; (3) argues with the husband; (4) refuses to have sex with the husband; and (5) burns food. The valid response options were yes (1) or no (0). Table 1.1 below shows the percent of men who agreed with each of the above statements about wife beating.

We consider each of the five scenarios as a dependent variable. In addition, a new variable representing men who agreed with wife beating in at least one of the situations was created. Therefore, there are six dependent variables.

Independent Variables

There are three sets of independent variables. The first set contains socio-demographic characteristics. This set includes marital status, age, education, and wealth index. Marital status has two categories: never married and (currently) married. We excluded divorced and other forms of unions because they may be directly or indirectly associated with domestic violence. For example, some men may have lost their wives through divorce or death; therefore, their answers to wife beating questions could be problematic. Age was regrouped into three categories: 15–24, 25–34, and 35+. Wealth index is a measure of level of wealth that is consistent with expenditure and income (Rutstein 1999). It is expressed in wealth quintiles: poorest, poor, middle, richer, and richest.

The second set of variables contains three sociocultural factors: type of place of residence (urban/rural), region of residence, and religion. The latter is very important in Ethiopia, where nearly half of the inhabitants are members of the Orthodox Church. Members of this religious denomination see women in the image of “Holly Mary” or “Saint Mary.” Therefore, we expect Orthodox men to be less likely to condone wife beating practices.

The third set of variables contains media exposure information. Respondents were asked about how often they read newspapers or magazines, listen to the radio, and watch television. Response categories for each of these three questions were the following: not at all, less than once a week, and at least once a week. Because they expose men to new ideas and the world, these variables are expected to be negatively associated with acceptance of wife beating.

Results

In this study, results show that a significant number of Ethiopian men agree with each of the statements about wife beating. About 3 in 10 men (30.1 %) agree that a husband is justified to beating his wife if she neglects the children; one-fourth (25.8 %) in case she goes out without telling the husband; and about the same percent (25.6 %) if she argues with him (see Table 1.1). Wife beating received lower approval in cases of refusal to have sex with the husband (21.2 %) and burning food (21.0). Apparently, Ethiopian men rank the safety and well-being of children very high. Nearly half of the men (43.0 %) agreed that wife beating is justified in at least one of the situations considered in this study.

The results of the binary analysis between each of the independent variables and the dependent variables are given in Table 1.2. The information in that table shows that married men agree more with wife beating than unmarried ones. Nonetheless, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of refusal to have sex with the husband and burning food. Age is significantly associated with all dependent variables, except one—going out without telling the husband. Overall, younger men seem to agree more that the husband is justified to beating his wife than do older men.

Education is negatively associated with agreement of wife beating in all circumstances considered in this study. In the same way, wealth index has a negative association with wife beating. Men who lived in poorer households were more likely to agree with each and all of the statements justifying wife beating than those men who lived in better-off households.

Each of the sociocultural factors examined here is statistically significantly associated with each of the dependent variables. Urban residents were less likely to agree with wife beating than their rural counterparts. In addition, there are important regional differences. For example, men in the S.N.N.P. region were the most likely to agree with four of the five wife beating statements than men in other regions: going out without telling the husband (37.6 %); neglecting the children (42.4 %); arguing with the husband (34.9 %); and burning food (34.2 %). Somali men topped the list for agreeing with wife beating in case of refusing to have sex with the husband (38.4 %). For each of the scenarios of wife beating, inhabitants of the capital city, Addis Ababa, reported the lowest level of agreements (from 1.7 % in the case of burning food to 5.8 % in the case of neglecting the children, and 9.5 % for at least one of the five reasons).

As for religion, the data in Table 1.2 show that compared to other men, men who are members of the Orthodox Church were significantly less likely to agree with three of the five causes of wife beating: neglecting the children (26.2 %); arguing with the husband (19.9 %); and burning food (17.7 %). They were second in disagreement of wife beating behind those men who belong to the Catholic Church on two wife beating statements: going out without telling the husband (20.5 % for Catholic and 21.9 % for Orthodox) and refusal to have sex with the husband (14.2 % for Catholic and 15.1 % for Orthodox). Overall, men who belong to Ethiopia Orthodox Church were significantly less likely to agree with at least one of the five statements of wife abuse as compared to men in other religious denominations.

Binary results on media exposure indicators are all consistent. Men who read newspapers and/or magazines, those who listen to radio, and those who watch television were more likely to disagree with each of the five statements of wife beating than their counterparts who had no or little exposure to these media. Are these differences still significant once the effects of other factors are held constant? To answer this question, we now turn to the multivariate analysis in the form of logistic regression models. The results are shown in Table 1.3, where we discuss these results along with the three sets of variables.

The Importance of Demographic Characteristics

The results of demographic characteristics in Table 1.3 show that the two categories of marital status considered in this study are not statistically different when all other variables are taken into account regarding wife beating for the following causes: going out without telling the husband, neglecting the children, and arguing with husband. In other words, Ethiopian men, whether married or not, share the same view on those situations. They do, however, hold different views regarding refusal to having sex with the husband and burning food. In these two situations, married men are significantly more tolerant than never-married men. No significant difference was found in the last model for agreeing with at least one reason for wife beating.

Age, education, and wealth index were significantly associated with lower acceptance of wife beating in all circumstances examined in this study. Such findings are consistent with the results from previous research in Ethiopia, especially that of Rani and associates (2004). In terms of age, our findings suggest that maturity leads to more understanding of gender relations. The negative association between the acceptance of wife beating and education shows that formal schooling seems to improve men’s view of women and thus reduces the use of force to correct what are considered bad behaviors within the Ethiopian context. As for wealth index, men who live in richer households are significantly less likely to approve of wife beating than those in poorer households. This is consistent for all scenarios, indicating that poverty may be a contributing factor of wife abuse in Ethiopia.

The Role of Culture

All three measures of cultural norms used in this study are statistically significantly correlated with attitudes toward wife beating. As we hypothesized, residents of urban places are less likely to agree that wife beating can be justified in any of the five circumstances, except in the last model in which we examined the case of men who agreed with at least one of the scenarios. The effect of the type of place of residence remained significant even when the region variable was excluded from the logistic regression equation (results not shown), proving that urbanization does play an important role in melting cultures and thus reducing the influence of traditional gender role views.

Region of residence is another very important variable of men’s attitudes toward wife beating in Ethiopia. Compared to Addis Ababa residents, men in all other regions are more likely to agree with each of the five scenarios that are the cause of wife beating. Nonetheless, there are significant differences across regions. For example, men from the S.N.N.P. region top the list in terms of agreeing with wife beating in cases of going out without telling the husband (odd ratio = 4.739), neglecting the children (odd ratio = 4.092), burning food (odd ratio = 5.115), and at least one of the five scenarios (odd ratio = 4.142). Somali men (men in Somali regional state) lead for justifying wife beating in cases of arguing with the husband (odd ratio = 3.399), and refusal to having sex with the husband (odd ratio = 5.630). Another interesting pattern is that of the Oromo men (men in Oromia regional state), who rank second after Addis Ababa in five of the six models in Table 1.3.

The third variable in this set is religion. Interestingly, belonging to Orthodox or Catholic does not statistically significantly affect men’s views on wife beating in all the six regression models. In contrast, compared to men in the Orthodox churches, those in the Protestant denomination were significantly more likely to agree with each of the scenarios of wife beating. The same was observed for Muslim men, except for burning food for which they were not significantly different from Orthodox and Catholic men.

The Impact of Media Exposure

Two of the media exposure variables are significantly associated with each of the six dependent variables in the multivariate models in Table 1.3. Those who read newspapers and/or magazines are significantly more likely to reject the views that wife beating can be justified in any of the scenarios proposed to them during the survey. More important, the relationship is even stronger for regular readers.

Although significant, the relationship between radio listening and men’s attitudes toward wife beating is not all linear. While it is true that weekly exposure to radio is associated with significant reduction of support to each of the six situations presented in Table 1.3, limited exposure is found to even increase support for wife beating, particularly in the case of refusing to have sex with the husband, which the association was statistically significant.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this chapter was to examine men’s attitudes toward wife beating in Ethiopia in order to provide a national profile of the situation, as well as determine socio-demographic factors associated with such views. The results show that nearly half of the men (43.0 %) agree with at least one of the five statements describing situations in which the husband is justified to beating his wife. However, there are some variations in men’s agreement across the scenarios: for example, whereas most men (30.1 %) agree with wife beating in case the wife neglects children, only 21 % agree that the husband is justified to beating his wife for burning food. Such a range of disagreement is largely due to the influence of men’s demographic characteristics, the cultural environment in which they live, and media influences to which they are exposed. The analysis of these variables in multivariate equations shows important results and confirms our presumption that men’s views on wife beating are rooted in their background characteristics and the sociocultural space.

In terms of demographic variables, the hypothesis that marriage influences men’s attitudes toward wife beating was not fully supported in this study. Instead, we found that married men are more lenient than never-married men in terms of wife beating in cases of refusing to have sex with the husband and burning food. The lack of significant differences between married and never-married men’s attitudes toward wife beating for other scenarios shows that those are high-ranking behaviors that most men condemn in Ethiopia. This is true considering the high percent of agreement accounted for those cases in descriptive and bivariate analysis sections of this chapter.

We also found that age, education, and wealth are important negative correlates of aspects of wife beating. Older men, those with higher education, and men in wealthier households are significantly less likely to agree with wife beating in any circumstance. This educational effect, which was also echoed in previous research (Rani et al. 2004), is an important policy variable. In the same way as scholars advocate for women’s schooling as a significant female empowerment and sexual health variable (Roudi-Fahimi and Moghadam 2003), increasing men’s educational attainment can significantly reduce wife abuse in Ethiopia. In addition, delaying marriage can also help, as older men show less support for wife beating. Naturally, wealth is a useful ingredient of marital harmony and gender relation, but its use in population policy is a daunting task.

This study also uncovered the key role of sociocultural factors in determining men’s attitudes toward wife beating in Ethiopia. As we hypothesized, rural men hold more conservative views on wife abuse, even after controlling for the effects of all other variables. For a country that remains essentially rural, urbanization is not an immediate policy variable for improving gender relations. Only 14.2 % of Ethiopians live in urban areas according to estimates by Schmidt and Kedir (2009).

Results on regional variations suggest that some parts of the country are more apt to condone wife beating than others. For example, given their high levels of agreement with wife beating justification statements, S.N.N.P. and Somali regions should be the target areas for any large-scale campaigns for reducing wife beating in Ethiopia. Our findings show that men in the Somali region of Ethiopia take wife submission very seriously and they support wife beating as a corrective action tool. Those in the S.N.N.P. region seem to use wife beating primarily for family cohesion rather than pure submission to the husband. Hence, unlike Somali men who are ranked number one for support of wife beating for refusing to have sex with the husband and arguing with the husband, S.N.N.P. men are number one in agreeing that the husband is justified to beating his wife if she goes out without telling him, neglecting the children, and burning food.

Religion, especially the Ethiopian Orthodox and Catholic religions, is deterrent to wife beating in Ethiopia. Men of the Orthodox Church and those in the Catholic Church were significantly less likely to justify wife beating, regardless of the woman’s behavior. In contrast, members of the Protestant denomination were significantly more likely to agree with all aspects of wife beating. Unlike Orthodox Church in which a woman is seen in the image of “Saint Mary,” the Protestant religion teachings encourage the woman to be submissive to her husband. This may explain why Protestant men are in support of wife beating more than men in other religious denominations.

Exposure to mass media has a negative association with wife beating. We found that men who read newspapers and/or magazines and those who listen to radio are significantly less likely to approve of wife beating than their counterparts who do not use these types of media. Because such media are linked to educational attainment, improving men’s education is again an important tool for combating domestic violence in Ethiopia. Therefore, as the country’s educational level rises (Kabuchu 2013), along with age at marriage (Save the Children 2011), we expect some improvement in gender relations, including a reduction in support for wife beating.

This study contributes to literature on intimate partner violence in two main ways. First, it covers the entire country and uses quantitative data to examine men’s attitudes toward wife beating. Previous studies were mostly qualitative works conducted in small areas (Abeya et al. 2012; Yigzaw et al. 2010). Second, this study explores the connection between socio-demographic variables and each of the scenarios in which husbands often use force as a mechanism for correcting their wives’ behaviors. By doing so, we were able to find key sociocultural factors of gender relations and propose practical ways to reducing men’s support for wife beating in Ethiopia.

References

Abeya, S., Afework, M., & Yalew, A. (2012). Intimate partner violence against women in west Ethiopia: A qualitative study on attitudes, woman’s response, and suggested measures as perceived by community members. Reproductive Health, 9, 14. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-9-14.

Assefa, E. (2013). Domestic abuse against women in Ethiopia: The price of not knowing her pain. Addis Standard. http://addisstandard.com/domestic-abuse-against-women-in-ethiopia-the-price-of-not-knowing-her-pain/. Accessed 26 Aug 2014.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (2008). World factbook. Ethiopia. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/et.html. Accessed 26 Aug 2014.

Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. (2012). Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, MD, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International.

Diop-Sidibe, N., Campbell, J., & Becker, S. (2006). Domestic violence against women in Egypt-wife beating and health outcomes. Social Science and Medicine, 62(5), 1260–1277.

Kabuchu, H. (2013). MGDF gender: Ethiopia LNWB final evaluation report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: UN Joint Programme on Leave No Woman Behind (LNWB). http://www.mdgfund.org/sites/default/files/Ethiopia%20-%20Gender%20-%20Final%20Evaluation%20Report.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2014.

Population Reference Bureau. (2013). 2013 World population data sheet. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. http://www.prb.org/pdf13/2013-population-data-sheet_eng.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2014.

Rani, M., Bonu, S., & Diop-Sidibé, N. (2004). An empirical investigation of attitudes towards wife-beating among men and women in seven sub-Saharan African countries. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 8(3), 116–136.

Roudi-Fahimi, F., & Moghadam, V. M. (2003). Empowering women, developing society: Female education in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: The Population Reference Bureau. http://www.prb.org/pdf/EmpoweringWomeninMENA.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2014.

Rutstein, S. (1999). Wealth versus expenditure: Comparison between the DHS wealth index and household expenditures in four departments of Guatemala. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro.

Salam, A., Alim, A., & Noguchi, T. (2006). Spousal abuse against women and its consequences on reproductive health: A study in the urban slums in Bangladesh. Maternal Child Health Journal, 10(1), 83–94.

Save the Children. (2011). Child marriage in North Gondar Zone of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Save the Children Norway.

Schmidt, E., & Kedir, M. (2009). Urbanization and spatial connectivity in Ethiopia: Urban growth analysis using GIS. ESSP2 Discussion Paper 003. http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/esspdp03.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2014.

World Health Organization. (2005). WHO Multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Country findings: Ethiopia. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yigzaw, T., Berhane, Y., Deyessa, N., & Kaba, M. (2010). Perceptions and attitude towards violence against women by their spouses: A qualitative study in Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopia Journal of Health Development, 1, 39–45.

Acknowledgements

Earlier results of this study were presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Southern Demographic Association held in Montgomery, Alabama, on October 23–25. The authors thank the conference participants for their comments and suggestions that helped improve the quality of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Djamba, Y.K., Kimuna, S.R., Aga, M.G. (2015). Socio-demographic Factors Associated with Men’s Attitudes Toward Wife Beating in Ethiopia. In: Djamba, Y., Kimuna, S. (eds) Gender-Based Violence. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16670-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16670-4_1

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-16669-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-16670-4

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)