Abstract

Staging laparoscopy is an important yet underutilized tool in the treatment of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. The principle goal of staging laparoscopy is to identify patients with operable primary lesions absent of macroscopic or microscopic metastatic disease. Despite appropriate preoperative radiographic staging, approximately a quarter of the patients with seemingly operable disease are in fact found to have occult gross metastatic lesions on staging laparoscopy. Moreover, patients with advanced lesions (serosal invasion, nodal disease) are particularly at a high risk of microscopic metastases into the surrounding peritoneal fluid. Sampling the peritoneal fluid for free tumor cells during laparoscopy identifies patients with microscopic metastatic disease, a diagnosis that portends a similarly poor prognosis to patients with gross metastatic disease. Identifying these patients prior to laparotomy not only saves the patient the morbidity of a needless major surgery but also prevents the delay of further chemotherapy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Once the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma has been made, proper staging of the lesion is fundamental to discerning what treatment options are available and appropriate for the patient. Most patients with gastric cancer will not be candidates for curative resection, and of those who are, many will go on to develop locoregional or distant recurrences. Accurate staging practices not only provide the best opportunity to select patients who will benefit from surgery, but also help to avoid subjecting patients to the morbidity of needless laparotomies.

Similar to other solid organ malignancies, tissue biopsy, and cross-sectional imaging is imperative to diagnosis and staging. As described previously, tissue diagnosis is usually obtained through gastric endoscopy, and radiologic staging is often accomplished with a combination of endoscopic ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT) with or without positron emission tomography (PET) . While these tests will indentify most patients with macroscopic metastases, a significant minority of patients harbor occult macroscopic metastatic disease in the abdomen or microscopic metastatic disease in the form of positive peritoneal cytology (CYT+). As these patients have poor overall outcomes despite removal of the primary lesion, they must be identified before attempting a therapeutic resection.

Staging Laparoscopy

In addition to the above modalities described, gastric adenocarcinoma—especially advanced lesions—should further be evaluated by staging laparoscopy. While the utility of staging laparoscopy in these patients has been addressed in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) gastric cancer guidelines, it remains a tool that has not been fully incorporated into the practice of American surgeons [1]. A retrospective review of Medicare data between 1998 and 2005 reported that only 7.9 % of the patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer had undergone prior staging laparoscopy [2].

Upon insufflation of the abdomen, staging laparoscopy is traditionally performed with a 30° laparoscope introduced through a 10 mm periumbilical port, aided by a right upper quadrant helper port with or without an additional left upper quadrant helper [3]. The peritoneal surfaces, liver, diaphragm, mesentery, omentum, and remaining abdominal surfaces are examined for signs of metastatic disease. At this time, biopsies with or without the use of intraoperative ultrasound are performed. While this may be performed immediately before planned gastrectomy, it is more and more being used as a separate staging procedure before the initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

After a thorough physical examination, CT is the most common form of staging in gastric cancer. It has the advantages of being both noninvasive and readily available. While it has the ability to identify a significant proportion of patients with inoperable disease, it is not a perfect means of evaluation. Several earlier studies, which employed at least preoperative CT, showed that as many as 30–40 % of the patients with what appeared to be operable gastric cancer were found to have visible occult metastatic disease on staging laparoscopy [4–10]. The accuracy of staging laparoscopy to detect the presence of abdominal metastases is frequently quoted to be > 90 % in most series [11].

Even with the advent of higher resolution CT, a 2006 study still reported 31 % of the patients were found to have occult M1 gastric adenocarcinoma at staging laparoscopy [12]. In a subset of these patients evaluated in further detail, tumors found to be located in the proximal stomach, body, or antrum without evidence of lymphadenopathy were at a lower risk for occult metastases, and may be candidates to avoid staging laparoscopy. A follow-up study at the same institution showed the adjunctive role that endoscopic ultrasound may play in discriminating patients with T3-4 lesions or nodal positivity, as they are at increased risk for occult disease [13].

Additionally, finding occult metastases on laparoscopy precludes subjecting patients to the complications of undergoing a potentially curative gastrectomy, a procedure in which over one-third of patients suffer a significant complication with nearly a 5 % perioperative mortality, based on national aggregate data [14]. In patients with M1 disease detected on staging laparoscopy, half will never undergo another intervention, and only 12 % will require a future laparotomy [15].

Peritoneal Cytology

The utility of staging laparoscopy, however, is not limited to its ability to detect occult visible disease. Sampling the peritoneal fluid during staging laparoscopy is now commonplace, as the likely mechanism of peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer is due to direct seeding of cancer cells shed from the primary lesion into the peritoneal fluid.

At the beginning of staging laparoscopy before manipulation of the primary tumor or biopsy of suspicious lesions, an aliquot of saline is placed into the peritoneal cavity and gently agitated. The fluid is then aspirated and traditionally sent for Papanicolaou staining to identify the presence of free tumor cells. Several newer studies have described additional genomic-level testing, but this is not standard [16, 17]. Lavage should be performed in the right and left upper quadrants to increase sensitivity [18].

Several hallmark studies have evaluated the role of peritoneal fluid evaluation and CYT+ status in patients with gastric cancer, specifically in those without evidence of other metastatic disease undergoing a potentially curative resection [19–23].

In these series, between 4.4 and 11.0 % of the patients will have CYT+, even in the absence of visible M1 disease. Increasing T stage or serosal invasion of the primary lesion was frequently found to significantly raise the risk of being CYT+. This is clinically relevant as CYT+ patients universally exhibited very poor outcomes. After curative resections, most of these studies reported survival in CYT+ patients to be around 1 year, compared to over 3 years or longer (Table 10.1). Moreover, Bando et al. reported a 100 % recurrence rate in CYT+ patients.

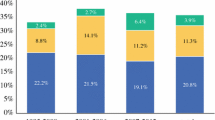

It can be concluded that CYT+ is a significant predictor of worsened survival. These findings prompted the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to reevaluate the staging of patients with gastric cancer to include the evaluation of peritoneal cytology. Based on these data, CYT+ is now classified as an M1 disease, even in the absence of other visible disease [24]. In fact, median overall survival in patients with isolated CYT+ disease is no different than those with gross abdominal metastasis at laparoscopy [25]. Interestingly in the Ribeiro et al. series, no patients with early lesions (≤ T2) were CYT+ [23]. This trend holds true in several subsequent evaluations; similar to evidence presented for staging laparoscopy in general, peritoneal fluid sampling has a lesser effect on therapeutic planning in early stage gastric cancer and may be reserved for only those who present with advanced lesions (Fig. 10.1).

Proposed algorithm for use of staging laparoscopy and peritoneal cytology evaluation in patients with gastric cancer. (From [28]. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons)

Treating patients with M1CYT+ disease with chemotherapy has been shown to improve survival (Table 10.2). Badgwell et al. reported a 7-month survival gain (total 16.2 months) over palliation alone [25]. A subsequent trial by Lorenzen et al. showed that 37 % of CYT+ patients were able to convert to CYT−; these responders had improved median survival compared to those who were persistently CYT+ (36.1 months vs 9.2 months) [26] and was again confirmed by Mezhir et al. [27]. Of note in the Lorenzen study however, is that even though the primary lesion may become resectable, perhaps as high as a quarter of the patients with locally advanced gastric lesions may progress from CYT− to CYT+ despite chemotherapy.

Treatment of CYT+ disease remains a novel area of focus [28, 29]. In addition to traditional chemotherapy administration, intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been evaluated. The theory behind this treatment is to eradicate free tumor cells and prevent them from seeding the peritoneum and abdominal viscera. A meta-analysis of three trials showed a trend towards improved overall survival (HR 0.70, p < 0.008), putting this forward as a potential treatment while awaiting further studies [29]. On a more basic hypothesis, a single, but intriguing randomized controlled trial by Kuramoto et al. has evaluated the effect of simply diluting out the free tumor cells by means of extensive intraoperative lavage [30]. In patients with locally resectable CYT+ disease who underwent surgery alone, 5 year overall survival was 0 %, compared to 4.6 % in those who received surgery with intraoperative peritoneal chemotherapy. This was in stark comparison to the 43.8 % survival in the patients who received surgery, 10 L saline lavage of the peritoneum, and intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Subsequent resection in these patients with complete peritoneal response with chemotherapy remains unclear. In a small subset of patients who converted from CYT+ to CYT− and underwent attempted curative resection, there was no improvement in median disease specific survival when compared to converters who did not undergo resection [27]. A small study by Okabe et al. does however report a survival advantage in highly selected complete responders who go on to obtain an R0 resection. This remains experimental, and at most institutions, patients with M1CYT+ disease will only undergo resection for palliation of symptoms.

References

Ajani A, Bentrem D, Besh S, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: gastric cancer 2013. Version 2.2013. www.nccn.org .

Karanicolas PJ, Elkin EB, Jacks LM, Atoria CL, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Staging laparoscopy in the management of gastric cancer: a population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(5):644–51, 51 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.07.018. PubMed PMID: 21872497.

Burke EC, Karpeh MS, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Laparoscopy in the management of gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1997;225(3):262–7. PubMed PMID: 9060581; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1190675.

Kriplani AK, Kapur BM. Laparoscopy for pre-operative staging and assessment of operability in gastric carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(4):441–3. PubMed PMID: 1833260.

Lowy AM, Mansfield PF, Leach SD, Ajani J. Laparoscopic staging for gastric cancer. Surgery. 1996;119(6):611–4. PubMed PMID: 8650600.

Stell DA, Carter CR, Stewart I, Anderson JR. Prospective comparison of laparoscopy, ultrasonography and computed tomography in the staging of gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83(9):1260–2. PubMed PMID: 8983624.

Asencio F, Aguilo J, Salvador JL, Villar A, De la Morena E, Ahamad M, Escrig J, Puche J, Viciano V, Sanmiguel G, Ruiz J. Video-laparoscopic staging of gastric cancer. A prospective multicenter comparison with noninvasive techniques. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(12):1153–8. PubMed PMID: 9373284.

D’Ugo DM, Persiani R, Caracciolo F, Ronconi P, Coco C, Picciocchi A. Selection of locally advanced gastric carcinoma by preoperative staging laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(12):1159–62. PubMed PMID: 9373285.

Romijn MG, van Overhagen H, Spillenaar Bilgen EJ, Ijzermans JN, Tilanus HW, Lameris JS. Laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasonography in staging of oesophageal and cardial carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1998;85(7):1010–2. doi:10.1046/j.1365–2168.1998.00742.x. PubMed PMID: 9692586.

Yano M, Tsujinaka T, Shiozaki H, Inoue M, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Takiguchi S, Imamura H, Taniguchi M, Monden M. Appraisal of treatment strategy by staging laparoscopy for locally advanced gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1130–5; discussion 5–6. PubMed PMID: 11036293.

Leake PA, Cardoso R, Seevaratnam R, Lourenco L, Helyer L, Mahar A, Law C, Coburn NG. A systematic review of the accuracy and indications for diagnostic laparoscopy prior to curative-intent resection of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15(Suppl 1):S38–47. doi:10.1007/s10120-011-0047-z. PubMed PMID: 21667136.

Sarela AI, Lefkowitz R, Brennan MF, Karpeh MS. Selection of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma for laparoscopic staging. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):134–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.015. PubMed PMID: 16399124.

Power DG, Schattner MA, Gerdes H, Brenner B, Markowitz AJ, Capanu M, Coit DG, Brennan M, Kelsen DP, Shah MA. Endoscopic ultrasound can improve the selection for laparoscopy in patients with localized gastric cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):173–8. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.022. PubMed PMID: 19228527.

Bartlett EK, Roses RE, Kelz RR, Drebin JA, Fraker DL, Karakousis GC. Morbidity and mortality after total gastrectomy for gastric malignancy using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Surgery. 2014;156(2):298–304. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.022. PubMed PMID: 24947651.

Sarela AI, Miner TJ, Karpeh MS, Coit DG, Jaques DP, Brennan MF. Clinical outcomes with laparoscopic stage M1, unresected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):189–95. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000197382.43208.a5. PubMed PMID: 16432351; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1448917.

Kelly KJ, Wong J, Gladdy R, Moore-Dalal K, Woo Y, Gonen M, Brennan M, Allen P, Fong Y, Coit D. Prognostic impact of RT-PCR-based detection of peritoneal micrometastases in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(12):3333–9. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0683-2. PubMed PMID: 19763694; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3275341.

Fujiwara Y, Okada K, Hanada H, Tamura S, Kimura Y, Fujita J, Imamura H, Kishi K, Yano M, Miki H, Okada K, Takayama O, Aoki T, Mori M, Doki Y. The clinical importance of a transcription reverse-transcription concerted (TRC) diagnosis using peritoneal lavage fluids in gastric cancer with clinical serosal invasion: a prospective, multicenter study. Surgery. 2014;155(3):417–23. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.004. PubMed PMID: 24439740.

Munasinghe A, Kazi W, Taniere P, Hallissey MT, Alderson D, Tucker O. The incremental benefit of two quadrant lavage for peritoneal cytology at staging laparoscopy for oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(11):4049–53. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3058-5. PubMed PMID: 23836122.

Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ. Prognostic value of positive cytology findings from abdominal washings in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83(5):672–4. PubMed PMID: 8689216.

Bando E, Yonemura Y, Takeshita Y, Taniguchi K, Yasui T, Yoshimitsu Y, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, Miwa K. Intraoperative lavage for cytological examination in 1297 patients with gastric carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1999;178(3):256–62. PubMed PMID: 10527450.

Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Shimizu Y, Torii A, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T. Peritoneal washing cytology: prognostic value of positive findings in patients with gastric carcinoma undergoing a potentially curative resection. J Surg Oncol. 1999;72(2):60–4; discussion 4–5. PubMed PMID: 10518099.

Bentrem D, Wilton A, Mazumdar M, Brennan M, Coit D. The value of peritoneal cytology as a preoperative predictor in patients with gastric carcinoma undergoing a curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(5):347–53. doi:10.1245/ASO.2005.03.065. PubMed PMID: 15915368.

Ribeiro U Jr, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Zilberstein B, Mucerino D, Yagi OK, Bresciani CC, Jacob CE, Iryia K, Gama-Rodrigues J. Does the intraoperative peritoneal lavage cytology add prognostic information in patients with potentially curative gastric resection? J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(2):170–6, discussion 6–7. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2005.11.001. PubMed PMID: 16455447.

Edge S, Cancer AJCo. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer; 2010.

Badgwell B, Cormier JN, Krishnan S, Yao J, Staerkel GA, Lupo PJ, Pisters PW, Feig B, Mansfield P. Does neoadjuvant treatment for gastric cancer patients with positive peritoneal cytology at staging laparoscopy improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2684–91. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0055-3. PubMed PMID: 18649106.

Lorenzen S, Panzram B, Rosenberg R, Nekarda H, Becker K, Schenk U, Hofler H, Siewert JR, Jager D, Ott K. Prognostic significance of free peritoneal tumor cells in the peritoneal cavity before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with gastric carcinoma undergoing potentially curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(10):2733–9. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1090-4. PubMed PMID: 20490698.

Mezhir JJ, Shah MA, Jacks LM, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Positive peritoneal cytology in patients with gastric cancer: natural history and outcome of 291 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(12):3173–80. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1183-0. PubMed PMID: 20585870.

De Andrade JP, Mezhir JJ. The critical role of peritoneal cytology in the staging of gastric cancer: an evidence-based review. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(3):291–7. doi:10.1002/jso.23632. PubMed PMID: 24850538.

Cabalag CS, Chan ST, Kaneko Y, Duong CP. A systematic review and meta-analysis of gastric cancer treatment in patients with positive peritoneal cytology. Gastric Cancer. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10120-014-0388-5. PubMed PMID: 24890254.

Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, Matsuo A, Yagi Y, Matsuda M, Yonemura Y, Baba H. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):242–6. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c80e. PubMed PMID: 19638909.

Okabe H, Ueda S, Obama K, Hosogi H, Sakai Y. Induction chemotherapy with S-1 plus cisplatin followed by surgery for treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(12):3227–36. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0706-z. PubMed PMID: 19777180.

Mezhir JJ, Shah MA, Jacks LM, Brennan MF, Coit DG, Strong VE. Positive peritoneal cytology in patients with gastric cancer: natural history and outcome of 291 patients. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2011;2(1):16–23. doi:10.1007/s13193-011-0074-6. PubMed PMID: 22696066; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3373003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

De Andrade, J., Mezhir, J., Strong, V. (2015). The Role of Staging Laparoscopy and Peritoneal Cytology in Gastric Cancer. In: Strong, V. (eds) Gastric Cancer. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15826-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15826-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-15825-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-15826-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)