Abstract

Despite a number of often cited advantages attaching to the implementation of cross-cultural training (CCT) programmes in preparing expatriate employees, research indicates that the amount of training undertaken can be modest. This chapter explores the use, role and perceived value of expatriate CCT in developing an expatriate management talent pool in internationalised Irish-owned MNCs. Drawing upon qualitative data from in-depth interviews conducted in twelve Irish MNCs, we highlight the uneven approach among MNCs to the provision of cross-cultural training largely arising from the urgency associated with many international assignments and the sporadic nature of these transfers. Despite this, all interviewees demonstrated an awareness of the potential value of CCT, and a majority openly articulated the potential of a formalised CCT initiative in supporting the expatriates’ likely success when on assignment. Where training interventions were provided, we unearthed a preference for a combination of cognitive and experiential approaches. Chief among the perceived benefits of CCT were its role in structuring expectations and its capacity to facilitate some cultural mastery.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

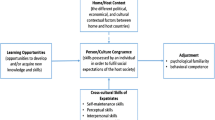

Finding and developing the talent required to execute international strategy is of critical significance to MNCs in order that they might reduce the liability of foreignness which they face [1]. This liability, arising from the cultural and institutional distance and idiosyncrasies, comprises a range of both surface and deep-level differences between the home and host location which the MNC encounters and which impacts the intercultural transitional adjustment processes of the expatriate manager when she/he is seeking to achieve good person–environment fit with the new host environment [2–5]. Bridging this hiatus demands a cadre of management talent with appropriate intercultural competence. This competence, at the individual level, in the form of personal attributes, knowledge and skills, is presumed to be associated with global career success and, at the organisational level, with business success through the more effective management of business operations [6]. The cumulative evidence from the international, comparative and cross‐cultural literatures on the attention paid to developing this competence remains mixed. This is critical because a lack of interculturally adept human capital may act as a significant and on-going means constraint on the implementation and execution of global strategy in an increasingly diverse range of host locations and result in a cohort of expatriate managers experiencing negative psychosomatic consequences arising from an underlying psychological discomfort with various aspects of a host culture .

In this chapter, drawing upon exploratory, qualitative data, we examine the use, role and perceived value of expatriate cross-cultural training (CCT) in composing and developing an expatriate management talent pool among 12 recently internationalised Irish MNCs . Conceptually, expatriate CCT, which is increasingly viewed as an important building block of the architecture of an integrated suite of congruent international human resource policies and practices, is understood to comprise of formalised experiential or cognitive interventions designed to increase the knowledge, skills and coping mechanisms of expatriates in order to assist them in multiple domain interactions and facilitate their adjustment to living and working in the novel sociocultural context [7, 8].

Literature Background

Operating within and across diverse contexts brings with it a bewildering variety of cultural and institutional specificities that make managing in this milieu especially complex with the result that, as Torbiorn [9] put it, many thousands of words have been devoted to the subject of the ideal candidate for overseas assignments and their associated complexity. The focus on achieving good fit between candidate and context is understandable because as Yan et al. [10] highlight, “the challenges involved in cross cultural assignments can be high for both the individual and the organisation” (p. 373), and it is often an experience which is characterised by “all too familiar and vexing difficulties” (p. 374). Chief among these difficulties faced by the expatriate manager are culture shock, transitional adjustment difficulties, differences in work-related norms, isolation, homesickness, differences in healthcare, housing, schooling, cuisine, language, customs, sex roles and the cost of living.

As a result of these and associated challenges, the development of a cadre of expatriate managers with distinctive competences who can manage the increasing complexity of running global organisations has become a key human resource management and human resource development priority for many organisations [11–15]. The increased necessity to provide CCT as part of the international assignment cycle is underscored by the changing patterns of global staffing emerging in MNCs and the complex roles these diverse cohorts of expatriates play in increasingly challenging, more varied and, in many instances, heretofore under-researched locations around the globe which have become hot spots for foreign direct investment, most especially the emerging markets, many of which are on a significant growth trajectory [16–23].

Conceptually, academics have classified expatriate CCT along two broad dimensions, namely pre-departure training and post-arrival training , and have pointed to its importance in maximising the benefits to be gained from the expatriate career move [7, 24–26]. As an intervention, it has been offered as a potential part of the solution to some of the difficulties encountered during the intercultural transitional adjustment process and a number of potential benefits have been claimed for it. For example, it has been argued that CCT may assist in the acquisition of skills, behaviours and coping strategies required by the expatriate, may help to decrease mistake-making in the interpersonal encounter, and contribute overall to reducing some of the negative effects of culture shock and the time to proficiency in the new cultural context. While a review of the evaluation studies conducted to date is beyond the scope of this chapter, there are several contributions in this genre. For example, Earley [27] compared participants’ performance following exposure/no exposure to documentary and interpersonal training interventions. On completion of the assignment, those individuals who had participated in both types of training received more favorable evaluations from their supervisors in terms of adjustment and work performance, while those who had received no pre-departure training were given significantly lower evaluations. In another account, Bird et al. [28] examined the effects of informational training which indicated that training increased the factual, conceptual and attributional knowledge of the participants leading them to suggest that such programmes may be a mechanism through which to establish cultural awareness, though they cautioned that “the impact of this knowledge on other factors believed to be associated with cross-cultural adaptation appears limited” (pp. 432–433). Specifically examining the value of pre-departure training, Eschbach et al. [29] explored repatriate employees’ retrospective assessments of the effects of the training on their adaptation to international assignments. Their assessment indicated that those who received rigorous CCT exhibited cultural proficiency earlier than the others. Additionally, those repatriates who had received such training had greater job satisfaction leading Eschbach et al. to conclude “that those with integrated cross-cultural training had a better level of adjustment and higher levels of skill development” (p. 285).

Caligiuri et al. [30] explored the relationship between the relevance of particular forms of pre-departure training and the emergence of more realistic expectations among a cohort of globally dispersed expatriates. The results of this study led Caligiuri et al. to suggest that “highly relevant CCT created either accurate expectations or expectations of difficulty prior to the assignment ” (p. 366) and have been instrumental in increasing the expectation of success and reducing the time taken to reach fuller proficiency in the host environment.

Beyond evaluation studies of this nature, systematic reviews of the impact of CCT are also a feature of the literature. In this genre, Black and Mendenhall [31], for example, reviewed twenty-nine empirical studies on the effectiveness of expatriate CCT programmes in relation to three anticipated outcomes, namely cross-cultural skills development, personal and family adjustment and performance in the host country, and concluded that these studies gave guarded support to the proposition of the effectiveness of CCT . From a methodological perspective, however, they noted that “more longitudinal studies are needed that include rigorous research designs, before definitive conclusions about the impact of training over time can be made” (p. 119). Morris and Robie [32] in their meta-analysis of the effects of CCT on expatriate performance and adjustment found overall support for CCT effectiveness in terms of facilitating expatriate success, while Littrell et al. [33] in a retrospective examination of 25 years of research between 1980 and 2005 concluded that while the evidence points to CCT being effective in enhancing expatriate performance overall, more empirical research was needed to make advances in the field.

Methodology

In order to further explore the role and perceived value of CCT in the development of an expatriate management talent pool among Irish MNCs , we conducted in-depth interviews in 12 Irish organisations that have internationalised in the last decade. The MNCs that participated in our research spanned six sectors including finance, air industries, construction, hospitality and the food industry. Interviews were conducted in all instances with the manager who was primarily responsible for implementing expatriate programmes in the MNC. These individuals were chosen as key informants capable of providing insights on the policies, practices and preferred approaches adopted by their respective MNC. Each of the organisations in the sample used was chosen in accordance with the following criteria, namely:

-

1.

The organisation had to be an indigenous Irish-owned company;

-

2.

The organisation had to have international operations; and

-

3.

The organisation had to be involved in sending employees abroad on conventional longer term expatriate assignments . MNCs that relied on frequent-flyer programmes and other non-conventional international assignees to conduct international business were not included in the research.

The interviews conducted were between 45-min and 2-h duration and all were recorded. Ten of the interviews were conducted face-to-face and one was via telephone as the interviewee was undertaking an assignment at the time. One respondent replied electronically via email arising from time constraints that precluded a face-to-face interview. In this case, we sent the interview schedule to this participant. Any gaps in information were dealt with in all cases with follow-up telephone interviews. The interviews were subsequently transcribed, and, following an analytic induction approach, the data were coded and structured to generate meaning (Table 5.1).

Findings

The Rationale for the Assignment

The key reasons underlying the initial employment of expatriates as part of the internationalisation effort varied somewhat. Six of the MNCs were focused on the expansion of current operations. To this end, responses included the following:

The original intention behind sending them abroad was business expansion and growth and secondly, we started using expats because, I suppose they’ve established a trust and have a track record with [the company]. They understood your market, understood your products and you maybe have trained them from inception into the organisation so they’d have valuable knowledge and you’d be sending them to other countries to develop and grow all those markets.

(Fin 2, Head of Learning and Development)

We originally started using expatriates merely to facilitate us to transfer technical and managerial skills and their purpose hasn’t changed since then.

(Hserv 1, Regional HR Manager)

Other MNCs posited capitalising on their employees’ core competencies as the primary incentive driving their corporate philosophy to deploying international assignees.

The main purpose at the moment is development, development of the individuals but with the acquisitions that have been made…people have been sent over because of their expertise, so senior people might have been sent over because of their expertise to assess the companies and to bring them up to date and make any structural changes.

(Cons 1, HR Manager)

It was a strategic decision that they took…our main growth over the next 3-5 years is going to be in the States, so that’s where our concentration is, that’s why we’re developing new businesses, we need expertise out there to build up the business.

(Food 1, HR Manager)

A further two interviewees pointed to the necessity to manage the subsidiary in accounting for their use of international assignees.

They took over, they acquired XXX in America and really they sent people out to manage the operations in America.

(Fin 1, Assistant HR Manager)

The majority of our operations are in Europe so it would be initially setting up new bases and then operating them.

(Air 1, HR Specialist)

The majority of the assignments were undertaken by males. Here, sectoral issues in terms of the nature of the industry in which the MNC operated or sociocultural context issues referring to the location being perceived to be less amenable or more challenging to female expatriates were cited:

It’s nearly 90 % male that go….I suppose its because if you think of the disciplines that people are coming from a lot are engineers, production people, I.T. you know traditional male roles really.

(Food 1, HR Manager)

It is because of the locations we have. We have placed women in Bahrain alright and when we had an operation in Dubai we placed women there because it is more Western and that worked out very well. We didn’t have a difficulty there. Whereas in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait we have had more challenges, also we have to follow the stipulations that the partner would put into the contract.

(Air 2, Training and Development Manager)

Our findings are consistent with that found in the broader literature regarding the motivations for using expatriates in the early stages of internationalisation and underscore the argument that control and trust are major motivators for using expatriates in setting up subsidiary operations, establishing new markets, along with socialisation and spreading the corporate culture .

The Approach to CCT

Various methods were employed in preparing expatriates. None of the MNCs adopted purely pre-departure training, two used post-arrival only, and three MNCs claimed to use no formal training interventions. Of note, five MNCs adopted an integrated approach to CCT. Representative of some of these different methods are the following remarks:

Most of our employees that join us would have induction training in XXX before they initially head out abroad and then they would have further induction training when they arrive at the location and then really they are left to get on with their job as such.

(Air 2, Training and Development Manager)

It’s very much left to themselves in terms of pre-departure training for themselves or the spouse; that wouldn’t be one of our fortes.

(Food 2, HR Officer)

Evidence from the participant organisations points to the existence of a combination of cognitive and experiential approaches , with a strong reliance on technical approaches to training.

Our training is focused on job and skills training.

(Hserv 1, Regional HR Manager)

For an engineer, depending if they had worked on the aircraft type before, they can start with one or two days training. If they haven’t, the training can take six weeks. So it really depends on the job itself. Its not really assigned by the level of the job, but by the actual job itself. The majority of the training that we do is related to the job.

(Air 1, HR Specialist)

Well, it [training] would depend on the role but I suppose if I was to pick a typical role of maybe the structured business desk, it’s a very specific area and it’s the technical competence of structuring products combined with the sales ability to go out and meet customers and talk them through it. So for example, if we were seconding somebody to London for that role and if they had never worked on the desk before…they’d get two months technical training in terms of each of the products, externally as well as our internal on the job programme.

(Fin 2, Head of Learning and Training)

Beyond the technical rationale , an emphasis on mentoring as a training technique, although not always operating in a formal capacity, was also in evidence.

Mentoring is always useful as part of the training process for somebody going into a new role to have someone else that they can bounce things off, someone who is not their direct boss or someone they are answerable to, you can ask stupid questions in confidence and I think its very useful.

(Cons 2, HR Director)

Closely aligned with the benefits of mentoring was the positive aspect of liaising with previous expatriates . This has been outlined above as an informal mechanism of informing prospective expatriates about their new location. The value of this approach is illustrated by the example of one MNC which normally did not engage in any formalised cross-cultural training . While this may not be regarded as formal training, it did have the benefit of informing expatriates about the likely experience they would face.

About two years ago, we had four or five assignees going to Poland at the same time so…we had an informal evening, so we brought the assignees into the company and we had evening drinks for the family and there was a number of people that had just come back so we arranged for them to come in and meet with them…to get to know each other and then they could discuss general issues and what the assignees should be doing, how they should be preparing themselves for going overseas.

(Fin 1, Assistant HR Manager)

By contrast, however, another MNC, while recommending such an approach, questioned the efficacy of relying on somebody else’s account of his/her experience. The interviewee remarked:

We encourage it because the more they know about a particular place before they go the better, although it does give them perceptions that may or may not be true because they are somebody else’s experience of it but the more, the more they are familiar with it and the more they feel familiar with it, usually the more successful the assignment will be.

(Fin 3, HR Management Team)

Interestingly, area studies approaches in the form of books and audio-visual training mechanisms appeared to be unexploited among participant MNCs . The response of one interviewee illustrated vividly that expatriates should assume a certain amount of autonomy and self-directed learning in this regard.

I think people going to another country should do their research anyway. I think it’s a bit naïve of them, maybe even a bit silly, to arrive in a country without having read up about it if you’re going to live there…we’re talking work professional here, we’re not talking about going on holiday…we’re talking about this is your career and you really should know about what you’re getting into and do some research and its so easy with the internet and stuff and if they haven’t done any research you know I’d wonder about them.

(Fin 3, HR Management Team)

Our research findings, however, indicated that the MNCs did not leave preparation solely to the discretion of the expatriate . Rather, the research suggests a strong emphasis on briefing expatriates before they undertake an assignment . This emerged as an approach even among those respondents who indicated they did not adopt any formalised training for expatriates, suggesting that some participant MNCs did not regard career counselling or informal briefing as a pre-departure training method. The following quotation demonstrates this.

To be honest we don’t do it [training], we paint a very real picture of on-campus lifestyle [reference to assignments in Pakistan] or the various different locations and what’s involved in it and we really endorse the fact that staff are 100 % aware and go in with their eyes open and know what they are getting themselves into as regards expat life and the highs and lows of that really.

(Userv 1, HR Specialist)

The managing director of the second utility service MNC described the benefit of using this informal approach:

It makes them happier if they’re going out if they’ve a reasonable feeling that they know what they’re getting into, that they know who to call if there’s any problems, that they know how the country handles itself etc.

(Userv 2, Managing Director)

(Cons 2, HR Director)

In relation to the experiential approaches adopted, several MNCs across the sectors espoused preview or “look-see” visits to the new location. One interviewee from the food sector indicated that these “look-see” visits provided the opportunity for expatriates to assess if they felt that they would be able to adjust to the environment.

If somebody says I’m not really 100 % content, that’s where we’d offer them a look-see visit…so people would go out for a week or two and that kind of gives them a sense of the challenge that would be there and if they’d be happy with that.

(Food 1, HR Manager)

Air 1 echoed this approach. The training and development manager noted that it allows the potential expatriate the opportunity to see how well they function in the location.

I would say capacity to cope and capability to cope with the environment are very important and if we have selected someone for a position, before we actually offer them a position, we normally fly them out to the location to meet the management team in the location to see how they get on for two or three days.

(Air 2, Training and Development Manager)

The experience of Construction 1 further emphasises the relevance of employing this approach to ensure unsuitable candidates do not proceed with the assignment .

They [the company] bring the expatriate over, they introduce them to the company, the people working there, get a job description for them…they stay about three or four days and then they come back. In the time I’ve been there, it’s only happened once that someone has decided based on the look-see not to proceed.

(Cons 1, HR Manager)

Overall, drawing upon the dichotomy in the extant literature the interviews are suggestive of a stronger emphasis on a preference for cognitive approaches to expatriate training with relatively little emphasis being placed on experiential techniques. As one would expect, the implementation of training practices incorporates pre-departure and post-arrival elements, depending on the particular approach being utilised.

The Perceived Value of CCT Initiatives Undertaken by Irish MNCs

We now turn our attention to assessing the degree to which the interviewees felt that the CCT initiatives assisted expatriates in adjusting to the host location and surviving the assignment . Support for adopting expatriate CCT was not universal among the participant organisations. Close to 50 % failed to provide any formalised training for expatriate assignees. These MNCs noted that the time element posed a serious hindrance to the implementation of pre-departure CCT practices . Participants also pointed to the sporadic nature of such assignments.

We don’t train the individuals. Usually it’s to do with time more than anything and our numbers aren’t absolutely huge. Normally we’d have six weeks, if even six weeks, for somebody going overseas…. their job here has to be replaced as well so they have to train somebody up more than likely here. There really isn’t time to do a formal training.

(Fin 1, Assistant Manager, HR)

Commenting that this approach had previously worked fairly well for them, the interviewee also noted:

There isn’t really a huge requirement for it, nobody has come back saying, “O, we should have formal training for people going out” because the people know their jobs and they’re going out for a specific skill, they are going out there to relate that skill back out there.

(Fin 1, Assistant Manager, HR)

A similar response emerged from other MNCs that acknowledge they do not provide expatriate training for incumbents.

Our areas are quite specialised and really people who are going out would be at a very, very senior level. So training wouldn’t really be a requirement at that particular level.

(Userv 1, HR Specialist)

There is no training for going abroad. If they’ve any problems they tend to come back to us with the problems but there’s no training in place. They’ve been doing this for over thirty years so it’s worked, whatever they’re doing it works very well but it’s just that they haven’t said that [expatriates would feel they had benefited from training].

(Cons 1, HR Manager)

The reason we don’t do that is we are specifically looking for people who have the experience and who have the expertise. As on occasion we have been asked to organise an assignment for the next day, we don’t have time.

(Userv 2, Managing Director)

There was some degree of scepticism among some of the participants with regard to the possibility of they being able to sufficiently train someone for the overseas experience.

It’s very difficult; you can’t really train somebody or give them any sort of training as regards cultures . What do you train, what do you include in your training? A culture is something that somebody will go out and embrace and they will either enjoy it or they won’t grasp it and to be honest with you we haven’t had any situations of the latter…so generally we haven’t really felt there’s a need….

(Userv 1, HR Specialist)

Finance 3 echoed these sentiments remarking that:

Pre-departure training would have to be very generic to cross the cultures and if it’s that generic, I don’t know how useful it is and I would think arrival training is more specific and more useful.

(Fin 3, HR Management Team)

This was not a universal view however. Finance 2, for example, recognised the value of providing some culture -specific training. In the course of the interview, this informant explained that some of the training may take place in headquarters and so the individual travels back to Ireland to receive some instruction relevant to his/her overseas posting. However, where cultural issues are involved, the organisation proposes localised CCT as more beneficial. To this effect, the training offered was specifically focused on the location to which the assignee was situated.

The one thing we would have noticed is that for certain pieces of training, they’re better off going locally than coming back to Ireland and probably the best example of that would be in Connecticut. We do design our own management programmes here but because a lot of it is localised to the Irish or the UK situation, it’s of more benefit for the staff members to attend a programme on the same subject but just with the cultural difference of having been in the US instead of in Ireland or the UK. It helps them adjust better, it helps them localise their knowledge and has a more relevant impact. I think that if we were looking most probably at the US I think that there’s a cultural difference, certainly in terms of leadership and leadership style between Ireland and the US so in order for her/him to progress if they’re leading an American team, they’re better to go and do a leadership development course that allows for that cultural difference.

(Fin 2, Head of Learning and Development)

This was echoed in responses from those who employed CCT as they highlighted the possible benefits to be secured from adequate preparation. Illustrative of this point are the following contributions:

Preparation, it’s the classic. You know if you fail to prepare, you prepare to fail so by preparing the staff member and giving them the proper tools that they need and the skill awareness that they need for their role, it ensures that they can hit the ground running when they get there plus in terms of building their own confidence for going to work with the new team that they feel that they have the benefit and I’d say thirdly that they’ve integrated with people that they probably are going to end up working a lot with…so it’s relationship building as well as everything else.

(Fin 2, Head of Learning and Development)

It gives them a better understanding of what to expect when they get there, the more that they understand before they go, the more of a chance there is that they will settle into living abroad and into the lifestyle or the job they go into when they get there.

(Air 2, HR Specialist)

One key benefit of providing such training, is probably familiarity with the host country…that people would get comfortable and familiar with it and two, primarily that the employee is happy and eased into the culture as quickly as possible and its got benefits for the company on the whole so it’s really about a smooth transition.

(Food 1, HR Manager)

One finding that is especially interesting here is that, regardless of whether they actually engage in CCT or not, all respondents agreed that expatriate training is a valuable and important organisational activity. The merits as perceived by those who employ cross-cultural training techniques have already been articulated; however, those who did not engage in formalised training programmes also showed an awareness of the potential benefits that such an approach would give to their organisation.

If we had the time I think it should be done, it would be of benefit. It definitely would help to prepare them a lot more going out but the time it doesn’t allow for it…If we were to start tomorrow again and if we had 50 people going out in three months time we could organise something formal then and I could see how it could be of benefit definitely.

(Fin 1, Assistant HR Manager)

As a HR professional, there’s always a benefit to training…I know that there is, there’s always a benefit from that side of things. But they do believe, I suppose they feel that it’s working… why fix it.

(Cons 1, HR Manager)

In summary, while several of the MNCs in our investigation failed to implement any formalized CCT interventions, there was a universal awareness of the potential value of such an approach. The main reasons offered for not implementing a CCT programme were the short-term pressures associated with many international assignments and the sporadic nature of some of the intercultural transfers. Another commonly cited reason was the seniority of the staff undertaking these assignments which may be regarded as an excuse in some quarters as seniority does not always guarantee the requisite skills and competencies to complete the task in a new market.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the global financial crisis has left many casualties in its wake and that those who have managed to survive will likely have experienced dramatic fiscal rectitude to reduce operating costs across the board. However, although key economic indicators suggest that a period of renewed growth and development is emerging, there remains an urgency to ensure that organisations do not suffer what has been described as “corporate anorexia” arising from the deep cuts that have been implemented and the likelihood of many organisations not having the expatriate management “bench strength” to take advantage of the opportunities that arise with the recovery (Jim Sillery, Global HR Consulting firm, quoted by Woodward, SHRM [34]).

Arising from internationalisation, we are witnessing labour mobility on a global scale, underscoring the importance of preparing a talent pool of expatriate managers for international roles in more challenging and culturally diverse arenas. This talent question has been referred to as the dominant human capital topic of the early twenty-first century [35]. And where effectively developed, deployed and networked, it is proposed as one of the critical capabilities that will distinguish successful global firms both now and in the future [36, 37]. Training in an increasingly shrinking, highly interdependent world is, Landis and Bhagat [38] noted “no longer a luxury, but a necessity that most organizations have to confront in a meaningful fashion” (p. 7). However, despite a number of often cited advantages attaching to the implementation of CCT programmes in preparing expatriate employees, research indicates that the amount of training undertaken can be modest. Arising from this, in this chapter, we sought to explore the use, role and perceived value of expatriate CCT in developing an international staff in recently internationalised Irish-owned MNCs. Drawing upon qualitative data from in-depth interviews conducted in twelve Irish MNCs, we unearth what is best described as an uneven approach among MNCs to the provision of such training largely arising from the urgency associated with many international assignments and the sporadic nature of these transfers.

Thus, while international assignments remain a key dimension of firms’ internationalisation efforts, the question remains to what extent sufficient attention is being focused on preparing employees for these critical roles. The recent “Talent Mobility 2020” report [39] paints a less than optimistic picture in this respect. Their data suggest that many respondents have failed to address the long-term trend towards globalisation in their talent management programmes; some 65 % acknowledge that their organisation lacked standard policies for managing the careers of international assignees. Our qualitative account here of recently internationalising multinationals provides some further discussion points in this respect. From an historical perspective, a limited emphasis has been placed on CCT, primarily due to concerns associated with cost, timing and the dynamics of the international assignment. Our interviews with these MNCs point to time constraints and a perceived lack of any major requirement to do so as the key factors limiting the use of CCT, along with the sporadic nature of the expatriate assignments being undertaken, suggestive of what may be characterised as a somewhat diffident emphasis on CCT as part of the internationalisation process among these organizations. In situations where they occur, CCT interventions appeared to be relatively well developed and were viewed as an important phase in expatriate role preparation. The MNCs that provided pre-departure training undoubtedly saw this as a necessary part of the expatriation process. Some MNC that did not engage in formalised pre-departure training did adopt post-arrival techniques, primarily as they felt that it facilitated faster adjustment or believed that training on site was more appropriate as it allowed for contextualisation to the circumstances of the local facilities. However, the fact remains that many MNCs did not provide any formalized interventions in CCT, despite acknowledging its likely value to the development of their talent pool of interculturally competent expatriate managers and to their overall internationalisation efforts.

References

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341–363.

Shenkar, O. (2001). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 519–536.

Van Vianen, A. E. M., De Pater, I. E., Kristof-Brown, A. L., & Johnson, E. C. (2004). Fitting in: Surface and deep-level cultural differences and expatriates adjustment. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 697–709.

Takeuchi, R. (2010). A critical review of expatriate adjustment research through a multiple stakeholder view: Progress, emerging trends, and prospects. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1040–1064.

Nolan, E. M., & Morley, M. J. (2014). A test of the relationship between person-environment fit and cross-cultural adjustment among self-initiated expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(11), 1631–1649.

Morley, M. J., & Cerdin, J. L. (2010). Intercultural competence in the international business arena. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(8), 805–809.

Caligiuri, P., Lazarova, M., & Tarique, I. (2005). Training, learning and development in multinational organisations. In H. Scullion & M. Linehan (Eds.), International human resource management: A critical text (pp. 71–90). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Parkinson, E., & Morley, M. (2006). Cross-cultural training. In H. Scullion & D. G. Collings (Eds.), Global Staffing (pp. 117–138). London: Routledge.

Torbiorn, I. (1982). Living abroad: Personal adjustment and personnel policy in the overseas setting. New York: Wiley.

Yan, A., Zhu, G., & Hall, D. (2002). International assignments for career building: A model of agency relationships and psychological contracts. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 373–391.

Morley, M. J., & Scullion, H. (2004). International HRM: In retrospect and prospect. Employee Relations, 26(6), 583–594.

Dickmann, M., & Harris, H. (2005). Developing career capital for global careers: The role of international assignments. Journal of World Business, 40(2), 399–408.

Friedman, V., & Berthoin Antal, A. (2005). Negotiating reality: A theory of action approach to intercultural competence. Management Learning, 36(1), 69–86.

Caligiuri, P., & Tarique, I. (2009). Predicting effectiveness in global leadership activities. Journal of World Business, 44(3), 336–346.

Morley, M. J., Scullion, H., Collings, D. G., & Schuler, R. S. (2015). Talent management: A capital question. European Journal of International Management (in press).

Aycan, Z. (1997). Expatriate adjustment as a multifaceted phenomenon: individual and organizational level predictors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(4), 434–456.

Garten, J. (1997). The big ten: The emerging markets and how they will change our lives. New York: Basic Books.

Hutchings, K. (2003). Cross-cultural preparation of Australian expatriates in organisations in China: The need for greater attention to training. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20(3), 375–396.

Collings, D. G., Scullion, H., & Morley, M. J. (2007). Changing patterns of global staffing in the multinational enterprise: Challenges to the conventional expatriate assignment and emerging alternatives. Journal of World Business, 42(2), 198–213.

Li, S., & Scullion, H. (2010). Developing the local competence of expatriate managers for emerging markets: A knowledge-based approach. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 190–196.

Okpara, J. O., & Kabongo, J. D. (2011). Cross-cultural training and expatriate adjustment: A study of western expatriates in Nigeria. Journal of World Business, 46(1), 22–30.

Brookfield Global Relocation Services. (2013). Global Relocation Trends Survey. Woodridge, Illinois, USA.

Horwitz, F. M., Budhwar, P., & Morley, M. J. (2015). Future trends in human resource management in the emerging markets. In F. M. Horwitz & P. Budhwar (Eds.), Handbook of human resource management in the emerging markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing (in press).

Scullion, H. (1994). Staffing policies and strategic control in British multinationals. International Studies of Management and Organization, 24(3), 18–35.

Scullion, H., & Donnelly, N., (1998). International human resource management: recent developments in Irish multinationals. In W. K. Roche, K. Monks & J. Walsh (Eds.), Human resource strategies: Policy and practice in Ireland (pp. 349–372). Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

Downes, M., & Thomas, A. S. (2000). Knowledge transfer through expatriation: The U-curve approach to oversee staffing. Journal of Managerial Issues, 12(2), 131–149.

Earley, C. P. (1987). Intercultural training for managers: A comparison of documentary and interpersonal methods. Academy of Management Journal, 30(4), 685–698.

Bird, A., Heinbuch, S., Dunbar, R., & McNulty, M. (1993). A conceptual model of the effects of area studies training programs and a preliminary investigation of the model’s hypothesised relationships. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17(4), 415–435.

Eschbach, D. M., Parker, G. E., & Stoeberl, P. A. (2001). American repatriate employees’ retrospective assessments of the effects of cross-cultural training on their adaptation to international assignments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(2), 270–287.

Caligiuri, P. M., Phillips, H., Lazarova, M., Tarique, I., & Burgi, P. (2001). The theory of met expectations applied to expatriate adjustment: The role of cross-cultural training. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(3), 357–373.

Black, J. S., & Mendenhall, M. (1990). Cross-cultural training effectiveness: A review and a theoretical framework for future research. Academy of Management Review, 15(1), 113–136.

Morris, M. A., & Robie, C. (2001). A meta-analysis of the effects of cross-cultural training on expatriate performance and adjustment. The International Journal of Training and Development, 5(1), 112–125.

Littrell, L., Salas, E., Hess, K., Paley, M., & Riedel, S. (2006). Expatriate preparation: A critical analysis of 25 Years of cross-cultural training research. Human Resource Development Review, 5(9), 355–388.

Woodward, N. H. (2009). Expats still essential, but recession changes their role. Virginia, United States: Society for Human Resource Management.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1062–1081.

Morley, M. J., & Heraty, N. (2004). International assignments and global careers. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46(6), 633–646.

Garavan, T. N. (2012). Global talent management in science based firms: An exploratory investigation of the pharmaceutical industry during the global downturn. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(12), 2428–2449.

Landis, D., & Bhagat, R. S. (1996). Handbook of intercultural training, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Price Waterhouse Coopers. (2010). Talent Mobility 2020: The next generation of international assignments. Gurgaon: Price Waterhouse Cooper International Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Morley, M.J., Parkinson, E. (2015). A Practice with Potential: Expatriate Cross-Cultural Training Among Irish MNCs. In: Machado, C. (eds) International Human Resources Management. Management and Industrial Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15308-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15308-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-15307-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-15308-7

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)