Abstract

Grief is a normal and personal response to loss that all will inevitably experience at some or various points of life. With increasing emphasis on clinical leadership, clinicians (e.g. doctors, nurses) are expected to handle more and more responsibilities including grief. Clinicians confront and/or experience grief on a scale more intense and more frequently than people may normally encounter in life outside a hospital. Historically doctors and nurses are not well equipped for providing skilled grief management, leadership and support. The failure to observe and address this reality may therefore pose a significant risk to the staff member, the grieving person and the organisation. It is thus incumbent upon management to develop a capacity for responding appropriately when this turbulence descends within the workplace This chapter attempts to contextualise grief and its consequences within the dynamic of the clinical setting. It highlights the importance of recognising the personal but subtle formative shaping through the grief experiences of both the grieving person and the carer or manager; and summarises some core understandings of grief and loss. It is suggested that good grief management within the clinical context, is both a necessity for organisational risk management and for staff care, with potential to enhance the quality or spirit of the workplace.

Everyone can master a grief but he that has it

—Much Ado About Nothing

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Grief

- Complicated

- Counselling

- Unresolved

- Management

- Loss

- Supporting colleague

- Assessment

- Response

- Bereavement

- Tips for health care professionals

- Gender

- Tolerance of differences

-

Grief is a normal and personal response to loss. People in grief seek and require the sense of belonging and support from peers.

-

Grief has much to do with loosening of attachment. It is a process of transition that the clinical leadership needs to understand and tolerate.

-

Compassion and development of a healthy resilient and flexible work environment is critical and central to grief care.

-

Understanding the relational complexity of role diffusion when moving from management to care of a staff member in grief is important.

-

Management should be aware that loss experience(s) may predispose staff to put clients, colleagues and/or themselves at risk, and should take necessary steps to protect them.

-

Early recognition of the signs and symptoms is essential for effective management of grief and its consequences.

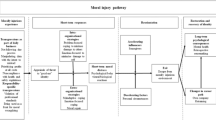

With increasing emphasis on clinical leadership , health care workers including medical staff, managers, and supervisors are expected to handle more and more responsibilities including grief . They also confront and/or experience grief on a scale more intense and more frequently than people may normally encounter in life outside a hospital. Historically doctors and nurses are not well equipped for providing skilled grief management, leadership and support. The failure to acknowledge and address this issue poses a significant risk to the staff member, the grieving person and the organisation. Effective leadership in the context of grief lies in the awareness, management and/or enablement of processes associated with loss and grief. This chapter briefly discusses the contemporary understanding of grief and its consequences, and suggests guidelines for its effective management at the workplace.

Grief and Loss

Grief may be defined as a response to loss . It is part of a normal process of adjustment to change. A grief response may range from being mild and transient to being intense and prolonged. Loss experiences can accumulate without being fully integrated and unresolved grief may contribute to a response which is seemingly more intense than warranted for a situation.

Grieving is as normal as it is complex. Loss is the shadow side of attachment, the deeper the attachment the greater the loss. Deep attachment however may not necessarily be a ‘healthy’ or life-giving attachment. It is an exhausting individual journey with no short-cuts. It is a road littered with potholes; a terrain sometimes never travelled before or at least a road less travelled [1]. It involves physical , emotional, psychological and social dimensions of living. Grieving is not a condition to be fixed but an unwelcome journey requiring companions along the way. These companions can be sometimes physically present, other times absent but not disconnected. The most important thing is not to add further regrets or resentments for the person to carry along this difficult road. The task is to provide road maps and nourishment for this journey. This is best achieved by empowering the bereaved person to recognise and mobilise their inner resources and the supports we can place at their disposal.

“If you touch one thing with deep awareness, you touch everything”

—Thich Nhat Hanh [2].

Thich Nhat Hanh speaks of the “Ocean of Peace” within each of us; he distinguishes between “the wave” and “the water” within the ocean. He speaks of the wave as a metaphor of the historical lived experience that each of us are in between being born and dying. The world of waves is the world of ups and downs, hopes and dreams and fears, success and failures , friendships and betrayals, attachment and loss . It is the world informed by the current and received historical context be that familial, cultural, or academic.

Loss will threaten equilibrium in our lives. Grief and loss is usually experienced as a time of intensity. Emotions are often intense and can range widely. It is a time for re-evaluating many things. Freud described grief as an attachment that has been lost and mourning as detachment from one who is loved. Since his initial work other theorists describe grief as stages [3], predictable, identifiable phases [4] to be experienced; and understood as descriptive rather than prescriptive, or a dynamic process of tasks to be achieved [5]. Building upon Freud’s earlier work, Bowlby has further explored attachment theory [6] but from a very different perspective. More recently the challenging work of Klass and Silverman [7] has drawn considerable consensus amongst practitioners for their construct of developing successful re-adjustment to loss through maintaining a continuing bond with the deceased.

Whatever the understandings behind our knowledge of the experience of grief it is always a profoundly personal, a unique and individual experience, and it is always the result of a reflective process. Living the turgid experience that loss causes is, while generic to being human, a universal experience.

Loss usually involves a transition process. The disequilibrium tends to engineer a shift in attachment to beliefs, work practices, relationships, and ways of experiencing the world. The workplace manager and/or colleague is confronted with the task of supporting a staff member going through such a transition while ensuring that risks to staff and patients and case management are minimised.

Understanding the Experience of Grief

Grief is about the human response or reaction to loss, often described as the objective state of having lost someone or something precious. There are many varied experiences of grief not related to death such as loss of a job, role or income; loss of youth, a limb or organ, hopes , dreams, reproductive capacity, identity or body image to name a few.

Bereavement is a term used for the objective state of the individual when the loss is a relational loss through the death of someone close whereas mourning describes the outward behaviour and symptoms of someone who has experienced loss. Mourning is a process sometimes culturally defined through cultural or religious practises.

Understanding grief is an evolving study not dissimilar to our evolving understanding of what constitutes biological death. Parkes [8] points out that in recent times more attention has been paid to the context in which grief arises and in particular the nature of the attachments that precede and influence the grief experience . Moving from the traditional concepts based in the psychoanalytical tradition of Freud, various researchers notably Kubler Ross, Parkes, and Bowlby have understood grief as a process of identifiable or recognisable stages/phases aiming for resolution. Resolution is achieved when the grieving individual has emotionally detached from what has been lost and has made new attachments. More recent understandings such as those of Worden [9] who aligns more closely with the early work of Freud define the mourning process as a system of tasks. A significant feature in his more recent work fits with the concepts of Klass, Silverman and others who speak of continuing bonds with the dead, “We now know that people do not decathlete from the dead but find ways to develop ‘continuing bonds’ with the deceased” [10]. This is an important feature of understanding and very useful in the clinical setting. Klass and Silverman suggest that in understanding the mourning process and supporting the grieving person the essential focus is not about detachment or letting go of the memories of the dead but of continuing bonds with the dead. They suggest that when a person dies the relationship does not die but continues in a different way, a re-location of the relationship. This understanding especially supports recent developed practise surrounding the death of a baby or a child where memory-making such as foot/hand prints, lock of hair; photos and rituals engage symbolically to focus upon the integration of the physical absence through actively supporting the ongoing connections or continuing bonds with the deceased. The use of outward symbols and specific language contribute to keeping the person alive in memory while enabling the grieving person[s] to pick up the threads of life again.

The role of Personal Experiences

Whenever we meet another at depth, especially in the helping relationship, we do not come in a vacuum as a value-free blank canvas. We come with our own life-story, values, beliefs, assumptions, prejudices and ways of coping with life’s pain or grief and unconscious or forgotten learning. If, for example, I have grown up in an emotional desert, deprived of deep nurture, of touch, hugs and affirmation and if my sense of wellbeing derives from being compliant with the needs of others above my own, when meeting a bereaved person my deep seated internal conditioning, unless well understood will most likely become the lens through which the other person’s story and pain is filtered. This lens is at least potentially irrelevant, more likely a hindrance, possibly a danger to the wellbeing of the other.

It is all too easy when listening to some story or issue to transfer our own meanings and emotions onto it, rather than to allow the truth to surface…. If people are not in touch with who they are and what they think important then it is difficult to see how that can know another (Palmer 1088). Their sense and appreciation of others and the issues they face will be clouded and cluttered with debris (2008, 20) [11].

When working with the grieving the greatest gift we bring is, as Kelly says, our reflexive self. this is the self I have reflected upon and with whom I have learned to relate gently and with compassion .

Sitting alongside the grief stricken there are no magic words to offer. There is no script to read, no prayer, no ritual or repository of wisdom that will lessen the pain of neither that moment nor the hours, days, weeks and years that will follow for that person whose life has intrinsically and explicitly changed. When establishing a supporting relationship in the context of another’s grief the following three criteria are essential.

-

1.

A realistic self knowledge: One’s own vulnerabilities, life grief’s and losses, fragilities and emotionally wounding experiences will be confronted from time to time, sometimes unrecognised until the moment. A realistic assessment of ones strengths and limitations, ones own narrative of social and familial conditioning and philosophy of life that includes the inevitability of death is an invaluable strength that will avoid transference of another’s pain or unhealthy self expectations.

-

2.

Understanding role differentiation, relational shifts and impact upon the inter-personal dynamics of the environment that such support of a bereaved staff member may require or initiate.

-

3.

Some basic knowledge about the phenomenon of grief in order to appropriately respond and build a level of competence and comfort for working with the bereaved.

Supporting a Grieving Colleague

Health care workers may particularly find it difficult to support a grieving colleague or the patient’s family members as they are trained in science and/or administration yet grief support is essentially a relational skill. Not having a tangible, immediate and effective “cure” may incur a feeling of frustration, helplessness or of having failed. The inability and undesirability of making a person feel better or happier may invoke feelings of powerlessness contrary to the aims of the medical profession. The grieving person’s family may likewise have expectations that the doctor or nurse is the expert and will “cure” or quickly resolve the family member’s grief. Consequently the person’s family may expect that the medical staff’s intervention will also resolve their anxiety and emotional pain felt in relation to their loved one. Healthcare professionals are often ill-equipped to manage such expectations and some emerging research is currently focussing on the vulnerability and suffering of health care professionals.

We come with self-inflicted pains

Of broken trust and chosen wrong,

Half free, half bound by inner chains [12]

When a colleague or staff member indicates by a certain manner that all is not well (e.g. a change in behaviour, work capacity or ethic), a tentative approach is usually necessary to negotiate the pain barrier and establish trust. It does not matter whether that barrier is of self-inflicted pain, broken trust, chosen wrong or any other cause; the truth is that we all carry a protective shield which needs to be negotiated.

To establish rapport means that we are attempting to connect with the other’s desire for relationship and core of peace while containing the emotional swirl of current pain. A primary task of the one seeking to exercise empathy is to contain their own personal dissonance and quieten themselves. This may require the exercise of assigning immediate work concerns and personal worries/ excitements to an internal place where they will not be forgotten but can reside such that the colleague who is hurting can have full, unbiased, non-judgemental attention.

The one who may respond to the offer of personal hospitality will discern whether or not the offer is safe and trustworthy. This is a very important process for it is a decision which will relate to the present moment; it will be taken in the context of the culture of the employing institution and in the context of a pre-existing relationship. In any institution there needs to be a balance between maintaining a position of power and authority within the structure and exposing one’s personal vulnerability.

An encounter grounded in empathy will require the exercise of courage by both parties . To engage personal concerns in the workplace introduces another dimension of potential concern or conflict. It is important for each party to discuss the impact of an expression of current concern on each person and how it resonates with the way the workplace operates. This is a vital negotiation to undertake as the risk of real and/or experienced betrayal is potentially extremely damaging.

Risk management is multi-focussed and involves keeping patients/clients safe, maintaining workflow, protecting self as supervisor/colleague and protecting the one who is experiencing loss . Retention of role and working within its boundaries even while exercising empathy is important for safety. A supervisory role that needs to alternate between administrative and technical concerns and empathic engagement is dependent upon clarity around role for safety. The one seeking to establish empathy must be very clear as to why they wish to do this and would need to disclose this to the staff member occupying a junior position. For example: “I observe that in the first three months of your placement you have been very enthusiastic and your work of high quality particularly in regards to (very explicit); in the last fortnight I notice a drop in your enthusiasm and when (explicit incident) happened and I am wondering if there is something here in the workplace that is contributing to this apparent change or if you have private concerns that may be impacting your work.”

It is probably most useful to be able to negotiate how the workplace can accommodate with some flexibility the needs of a staff member who is engaging a process of loss. In summary, line management versus a humble desire for the wellbeing of a work colleague.

Tips for Health Care Professionals, Managers, Supervisors

Health care professionals are not expected to be experts in the field of grief care but they must have the basic knowledge and confidence as to what is appropriate grief care for those who are experiencing significant loss. Historically the medical/paramedical teaching institutions have viewed loss and grief education as an area for specialists such as psychologists and chaplains. A recent review of health profession courses (6 universities in Australia) requiring grief education has reported that only one course provided a unit dedicated to grief and loss [13]. The consequences of this being many health care professionals andmanagers feel inadequate to support those who are grieving [14]. Unless managers are equipped to alter a clinical culture that assumes grief care to be a specialist area of chaplains, social workers or psychologists staff stress will be increased through feelings of inadequacy when working with families experiencing the death or potential death of a patient. Subsequently they will not be empowered to adequately support patients, their families and importantly their colleagues experiencing grief [15].

Grief is a normal response to loss and bereavement is the lived experience of a loss. It is important to normalise grief and unless specific complications exist the essential task is to support what is occurring.

When working alongside people who are grieving we also bring our own experiences of loss and grief. These experiences or patterns may not necessarily be of healthy grieving. The relationship may therefore include theirs and our own morbidity. Recognition of the boundary between our own inner fears of incompetency, personal identity and professional identity becomes very important. It is not unusual for a grieving person to inadvertantly remind the carer of someone familiar in their own experience, either through personal mannerisms, visual presentation, tone of voice, language or gestures. This can be quite off-putting and require careful self assessment of responses, reminding oneself that this person is not the person of ones previous experience and not to transfer the feelings associated with the uncomfortable of similarity into a basis of response.

Assessment

Grieving is complex , it includes physical, spiritual, emotional and social dimensions. Assessment includes aspects such as what is this grief about; what or who has been lost or what language or descriptors are being used to describe it? Is there a religious or symbolic language used and what is its focus? Has the person had any previous losses? Who are the key persons involved; does the person have a strong, weak or non existent social support; what internal resources does the person demonstrate? What does this indicate for the focus of care? What body language is observed, and what might this suggest? If there are others present, what are they saying about the deceased or the person being supported or the relational dynamics occurring?

Response

It is critical not to have a pre-conceived expectation of how the person[s] will act. It is more likely that a staff member will be withdrawn or teary even distraught at times. The initial breaking of bad news may exert a very wide range of response. This may initially be physical such as shouting, screaming or hitting a wall. This can be very disconcerting, even confrontational but discern whether the aggression is directed towards yourself or an inanimate object. According to Kast [16] referring to Parkes and Bowlby [17] anger follows a break out of numbness and corresponds to the personality of the mourner and is accompanied with corresponding phases of deep dejection. In addition it seems to be channelled either towards doctors or to relatives who are perceived not to have done the right thing. This explains a not unusual experience when working with the grieving in the clinical context . When confronted with an angry response only intervene or react to it if the person, you or others are at risk. Remember that grief is a very dynamic process containing a very broad range of feelings, often conflicting. Acknowledge the contradictory nature of the experience including those of denial, anger, shock, blame or sadness. Don’t seek to give explanations or answers but affirm the normality of this. Remember the experience is both continual and a continuum in which people will move up and down. Some may withdraw and become isolated. While it is quite appropriate for people to want to withdraw and be alone in their grief, becoming isolated is not healthy. This is where a colleague, friend or manager, observing this may look for an appropriate way to circumvent it. Others lacking self confidence and social or personal supports may become overly dependant. While encouraging people to ask for what they want is useful and recognises their own strength, it requires careful management of boundaries by emphasising and practising carefully defined lines of support.

Gender and Tolerance of Difference

Male and female relationships are complex and sometimes severely tested through a loss experience . Gender differences in grieving are well documented [18] but differences also exist through the maturity of the relationship. Relationships that are tolerant of difference are usually less brittle, less disengaged, more fluid and consequently more resilient. These will cope better than those relationships with less tolerance of difference. For many couples the experience or integration of grief follows very different patterns that can in part be described as opposite experiences. For example she needs to talk about the loss, continually go over it, try to recall every little detail while he may feel uncomfortable about this and want to look forwards and not backwards. In the clinical environment a female staff member may be feeling very isolated and lonely in her grief due to her internalising or processing the experience very differently to her partner. He may be also feeling very isolated in his workplace due to a lack of recognition that he has submerged his grief in order to support his partner through taking on a protector role. He could also be embarrassed to express his feelings, often fearing that he may not be able to control his tears. Men may tend to grieve alone, are often uncomfortable expressing their pain to their partner but may do so with a woman with whom there is no relationship except possibly a working relationship.

In order to work effectively with the grieving, health professionals need not only an adequate knowledge base and skill level, but also the ability to recognise the limits of ones comfort zone, and give the unspoken message, a commitment, to the bereaved that right now I do not want to be anywhere else than here to support you as a colleague.

Complicated Grief or Complicated Lives?

It has been said that there is no such thing as complicated grief , only complicated people! Clinical experience and the evidence leave little doubt about the truth of the proposition that much psychiatric illness is an expression of pathological mourning.

In order to understand attributes of complicated or abnormal grief, chronic sorrow or delayed grief it is important to clarify what is understood as normal grief. Worden [19] categorises normal grief under four general categories, feelings, physical sensations , cognition and behaviours. Complicated grief is more difficult to define and the literature does not show consensus. It is reasonable to define normal or functional grief being raw, intense and varied in response especially in the initial period, but no single response or behaviour lasts. The carer is thus required to have very broad boundaries of acceptance of a variety of behaviours especially in the initial phase. Complicated or abnormal grief is different in that a person becomes stuck and beliefs or behaviours persist instead of being transient. It may present as being boundless and overwhelming with no predictable end, a self perception of overwhelming sadness representing life’s disappointments and fears. It is mostly cyclic, sometimes intensifying progressively over time and can be triggered by internal or external stimuli. Factors of past history, previous losses, life circumstances, attachment as investment in the meanings of the loss such as loss of a pregnancy or of person who has died may trigger these reactions. Psychologically unhealthy religious beliefs, domestic violence, substance abuse or cultural complexities may contribute to complicated grief. Specialised and prolonged treatment may be required to avoid deeper or ongoing damage, family breakup or psychological or psychiatric illness when a person becomes stuck in their experience. The essential task of most health professionals and managers is to be able to recognise complicated grief and provide the resources for the person to address it.

Key Points to Remember When Working With the Bereaved

-

1.

Listen deeply, develop empathy, ask questions, don’t assume anything, or say that you know what the other is enduring, that is unless you have been in their shoes, even then be careful not to overshadow the conversation with your own experience.

-

2.

Wherever possible be prepared to provide a continuity of care over a long period of time. Grief is more like a journey than a moment or particular time.

-

3.

Do not try to give existential answers or a rational reason for what has occurred, most times it is unreasonable and does not make sense and may not fit with the presumed pattern of life or notions of justice or fairness. Put differently, do not deny what has occurred.

-

4.

There is no urgency, if necessary slow it down, for the grieving person it may be that things are going too fast, there is no urgency. You will make mistakes or sometimes say the wrong thing. While the bereaved are usually very emotionally brittle especially in the early days or weeks of bereavement they will forgive you if they also experience your care, warmth and empathy. In the words of Shakespeare “Everyone can master a grief but he that has it”. (Much Ado About Nothing

Summary

Providing good grief care at the workplace is not easy for clinicians and managers who are trained and steeped either either within the scientific world of medicine or administration. The challenge is twofold. Firstly to enter the relational world of human dynamics and through this to develop best practise bereavement care for staff members. The imperative for undertaking this will in part be a strategy of risk management or harm prevention so that a grieving or distressed staff member does not put the patient, themselves or the organisation at risk; the second imperative will be a change in the organisational culture towards the provision of a more flexible, assured, professional and appropriately compassionate workplace. Providing a flexible and negotiated structure while allowing a colleague to transition through their experience of loss and grief involves taking a different type of risk. It requires a management approach based on trust, compassion and on the ability to negotiate different working parameters. The internal horizons of either party will shift and decisions may be made that involve separation. The rewards will be in terms of risk reduction, loyalty, re-investment in the workplace and/or profession. The culture of the workplace will be challenged towards change if a compassionate approach to loss is consciously engaged. We believe that such a change may be more a necessity than an option.

References

Scott Peck M (1978) The road less travelled. Touchstone, New York

Thich Nhat Hanh Maintaining emotional wellbeing in the intensive care unit: A grounded theory study from the perspective of experienced nurses. Siffleet, J. Unpublished Masters Thesis Curtin University 2011

Kubler Ross E (1969) On death and dying, MacMillan, New York (Parkes M Bereavement: studies of grief in adult life. Pelican, London 1978

Rando T (1993) How to go on living when someone you love dies. Lexington Books, Lexington

Worden WJ (2009) Grief counselling and grief therapy—a handbook for the mental health practitioner. 4th edn. Springer, New York

Bowlby J (1983) Attachment and loss, vol. 1, 2nd edn. Basic Books, New York

Klass D, Silverman PR, Nickman SL (1996) Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief (Death education, aging and health care). Routledge, New York

Parkes CM (2002) Grief: lessons from the past, visions for the future. Death Stud 26:367–85

Worden WJ (2009) Grief counselling and grief therapy—a handbook for the mental health practitioner, 4th edn. Springer, New York

Klass D, Silverman PR, Nickman SL Worden WJ. (2009) Grief counselling and grief therapy, a handbook for the mental health practitioner, 4th edn. Springer, New York, pp 39–56

Palmer 1998 The courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teachers Life. San Fransisco: CA: Jossey-Bass in Kelly E (2012) Personhood and presence, self as a resource for spiritual and pastoral care. T & T Clark Int, New York p7

Wren B (2005), p 484 [Contemporary hymn writer] in Kelly E (2012) Personhood and presence, self as a resource for spiritual and pastoral care. T & T Clark Int, New York

Breen LJ, Fernandez M, O’Connor M, Pember AJ (2012–2013)The preparation of graduate health professionals for working with bereaved clients: an Australian perspective. Omega (Westport) 66:313–32

Charles-Edwards D (2009) Empowering people at work in the face of death and bereavement. Death Stud 33:420–36.

Dunkel J, Eisendrath S (1986) Families in the intensive care unit: their effect on staff. Ann Emerg Med 15:54–57

Kast Verena (1988) A time to mourn, growing through the grief process. Diamon Verlag, Switzerland (Am Klosterplatz, CH-8840 Einsiedeln

Bowlby J (1980) Loss, sadness and depression. Hogarth Press, London

Overbeck B She cries, he sighs. Publications for transition loss and change. TLC Group. Griefnet Library, PO Box 28551 Dallas TX 75228

Worden WJ Grief counselling and grief therapy. A Handbook for the mental health practitioner, 3rd edn. p 35–39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Anderson, R., Collins, ML. (2015). Managing Grief and its Consequences at the Workplace. In: Patole, S. (eds) Management and Leadership – A Guide for Clinical Professionals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11526-9_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11526-9_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-11525-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-11526-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)