Abstract

This chapter presents initial observations of a pilot that introduces mindfulness meditation into teaching and university life. Short meditations were offered at the start of Year 1 and 2 lectures, besides weekly drop-in sessions. The purpose was to enhance the student experience through the affective domain, identified by Thomas 2012 as a key factor in improving retention. Contemplative practices (CPs) consist of enhancing awareness of the ‘here’ and ‘now’, characterised by the foregrounding of ‘being’ and ‘living’, rather than ‘doing’ or ‘knowing’. Thus, it could be argued that CPs have the potential to enhance the affective dimensions of the student experience and thus, indirectly, impact positively on retention. Students and staff perceived benefits that applied to learning and teaching specifically, but also to broader dimensions of their personal life. Overall there was enthusiasm from both students and staff for the innovation and a request to continue and expand current provision.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Contemplative practices (CPs) provide a non-traditional format for learning and teaching. They involve enhancing awareness of the ‘here’ and ‘now’ and are characterised by the foregrounding of ‘being’ and ‘living’, rather than ‘doing’ or ‘knowing’ and these practices are complimentary to the critical scientific frame of mind generally foregrounded in HE. This chapter presents observations of a pilot project that introduced CPs into teaching and life at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. This was a practice-focused project rather than an experiment. The focus of the evaluation was therefore on participant perceptions rather than on measurable impact. The initiative was funded as part of a University-wide project to enhance retention and widen participation; it was however not possible to establish causal links with CPs. The purpose was to enhance the student experience through the affective domain, and to facilitate learning, teaching and general well-being. Short meditations were offered at the start of Year 1 and 2 lectures across two modules; there were two introductory presentations and weekly drop-in sessions each semester . An eight-week mindfulness foundation course was offered to students and staff in semester 2. Students and staff perceived benefits that applied to learning and teaching specifically as well as to broader dimensions of their personal life. Some responses suggested that the project also made a contribution to retention. Some staff were unsure about the application of contemplative practices in their teaching and some students perceived them as waste of lecture time. However, overall students and staff agreed that the University should continue and expand current provision of CPs.

Introduction

Mindfulness meditation is humanizing the higher education environment by teaching to the whole student rather than just concentrating on the cognitive. (Eric McCollum quoted in (Anonymous 2013))

The last 10 years have seen a marked increase in interest in the application and integration of contemplative practices (CPs) in HE as a non-traditional format to enhance learning and teaching (Hart 2004; Bright and Pakorny 2012; Langer 1997; Palmer and Zajonc 2010; Ramsburg and Youmans 2013; Rose 2013; Altobello 2007). Figure 19.1 provides one perspective of the potential range of contemplative practices and highlights the diversity in possible approaches to contemplation in Higher Education. The point of the ‘tree of contemplative practices’ is not to map all existing practices, but to indicate the possibilities for such practices and make us aware that these can involve both active and passive elements, inner and outer dimensions, creative and interpretative deeds. Indeed, as the foundation of CPs is ‘awareness’ or ‘mindfulness’ (de Mello 1990; Kabat-Zin 2009), any activity that consciously engages participants in such awareness, may be called a contemplative practice. While it might seem useful to attempt a more or less accurate definition or description of CPs here, in order to come to an actual understanding of what they entail one must experience them. It is impossible to know what contemplation, mindfulness and meditation are by just reading about them. It is therefore in a sense also an anachronism to write an intellectual, analytical account of people’s experiences of CPs (as the rest of this chapter attempts), as no quantity or quality of other people’s positive or negative experiences should possibly have any bearing on your individual CPs. In other words, you may be convinced to give it a try, or you may be put off and never give it a try, or you may remain unsure whether your own already existing experiences with CPs could or should translate into integrating them into your teaching. But only by actually living with CPs will you be able to discover this. CPs are not then ‘techniques’ or ‘tips and tricks’ to improve learning and teaching, unlike other pedagogical approaches, such as group work, or reflective journals, where the teacher can effectively apply these approaches without him/herself engaging with them. Instead, the effective integration of CPs in our work with students must be underpinned by a living experience of the practices and their influence on one’s own life and work.

The initial fostering of such pure awareness generally starts with learning to be still, the idea being that by doing nothing we are afforded a moment in time and a place in space to observe what actually goes on in the world, both within ourselves and around us, when we don’t participate in it in the busy way we normally do. Subsequently we may guide our attention to the breathing that goes on, irrespective of our conscious awareness, to an object, or to an idea and allow these to simply be, without the usual analytical and critical faculties taking over the flow of thoughts and feelings. Thus, the philosophy underpinning this project was ‘engagement in contemplative practices’ and the project funding (see below) was primarily employed to create opportunities and resources to enable students and staff to engage with some commonly used practices. As experience was at all times prioritised while abstract intellectualisation without experience avoided, I would now also like to invite you, the reader, to spend 10 min listening to and engaging with the short meditation at http://www.meditation-for-beginners.net/media-files/beginnersmeditation.mp3, especially if you are unfamiliar with CPs or in any way uncomfortable with words such as ‘contemplation’, ‘mindfulness’ and ‘meditation’. Please just momentarily suspend your judgement and try it, before you proceed to read the rest of the chapter.

If you did just go through the above short meditation , then it is quite likely that you now feel calmer, more focused and less rushed and have some idea of what is involved. In our science-dominated contemporary society, which includes Higher Education, the terms ‘contemplation’ or ‘meditation’ tend to be associated with religious or other spiritual practices. In Universities especially, these terms tend to be shunned from dialogue and from academic life, on the implicit understanding that such subjective, apparently non-empirical approaches to knowledge and understanding do not belong within the realm of the Academy, except perhaps as an object of study. Nevertheless, it could be argued that the very existence of our Universities is based on the ability of its academics and students to contemplate, to think deeply, to ponder in order to produce new knowledge and understandings (see for example Altobello 2007). After all, new understandings and knowledge tend to be the result of creative, rather than purely logical deductive mental processes (Claxton 2006; Craft 2006; Brady 2007; Rose 2013; Altobello 2007). In the university context the term ‘reflection’ is ubiquitous, but this concept has become so seriously eroded that its meaning often just refers to ‘thinking’ in general. It is exactly in trying to reclaim reflection as ‘slow thinking in solitude’ that Rose (2013) argues for the need to put the contemplative dimension back into it (Oberski 2012).

Partly as a result of the rapidly expanding interest in one particular approach to contemplation, namely mindfulness meditation , it is now becoming more acceptable to discuss contemplation and introduce mindfulness and other contemplative practices into university life, for both students and staff. The evidence base for the potential benefits of mindfulness and also of other approaches to meditation, is growing almost exponentially (Chaskelston 2013) and mindfulness meditation has been implemented with great success in a variety of contexts (see for example London Transport (Halliwell 2009) and case study in Anonymous 2012). The following examples employ primarily secular contemplative practices without any specific religious affiliation or ritual, with the exception perhaps of the use of a meditation bell to mark the start and end of a session (derived from Buddhist practices). Regular engagement with CPs enhances attention, information processing and academic achievement (Shapiro et al. 2011). CPs seem to address specific cognitive dimensions as well as a general sense of well-being, thus to address both the affective and cognitive dimensions of the student experience. Additionally, CPs have (mental) health benefits (e.g. stress-reduction, pain management (Kabat-Zin 2009; Williams et al. 2007; Paul et al. 2007; Sillito 2012). A recent meta-analysis of the psychological effects of meditation confirmed that meditation practices are more effective in enhancing a range of psychological variables than relaxation exercises by themselves (Sedlmeier et al. 2012) and Ramsburg & Youmans (2013) showed that a short meditation before a lecture improved test scores, especially in first-year students.

None of this should come as a surprise. Anyone engaged with technology, email, social media and the online environment will know that the challenge is no longer to accumulate knowledge, but to make sense of the unmanageable amounts of it (Rose 2013). Our universities are still modelled on the idea that textbooks are expensive and out of date by the time they appear in print and that therefore a student needs to go to where knowledge is created in order to learn the latest findings in a field. Nothing could be further from the truth in the twenty-first century. I estimate that roughly 99 % of the knowledge students need to succeed in their studies is available online. But 100 % of the thinking required to succeed in their studies needs to be done inside their heads. So, unless I am a most inspiring lecturer, or I only lecture on my latest yet unpublished research, my time with students is much better spent in deepening their understanding than in adding to their knowledge. This means that as an educator I perhaps need to rethink how I work with my students when I see them face to face or interact with them at a distance. All this is already subsumed under Biggs’ notion of constructive alignment (Biggs and Tang 2011, p. 389) which builds on the constructivist understanding of learning that students learn by being actively engaged with subject matter, so that the role of the educator is no longer to supply knowledge, but to design learning so as to activate the students within the realm of the subject’s learning outcomes . However, I would argue that we now need something more than this. We need to give students more guidance on how to think deeply, on what to do with knowledge, on how to synthesize all this material (Altobello 2007; Wang et al. 2013). And these processes are not just about learning to think logically, although in can be argued that even in logical thinking one first needs to have a feeling for what logic actually is. This means we need to help students to reflect deeply, slowly and often in solitude (Rose 2013) on the concepts and ideas that they read about. This allows them to temporarily leave aside the quantities of information, concepts and ideas and instead to reconnect with their own being through which, after all, they engage with the world around them. Without such deep affective connections, subject material for many students remains at the level of information that needs to be instrumentally applied to problems in order to pass exams, rather than a body of living knowledge through which they can and wish to create a better world. We therefore need to create spaces, both physical and in time, in which they can do this. Even allowing for short periods of silence during a lecture, in which students are asked to contemplate a concept, or simply to allow what they have heard to sink in, by stilling the mind of distracting and irrelevant thoughts (Zaretsky 2013) is an example of introducing contemplation in the classroom. This example also suggests that while we academics use contemplation as a matter of course in our research and teaching, we may mistakenly have assumed that our students know when, why and how to contemplate and that they actually do this naturally as part of their learning (Altobello 2007).

This chapter describes some of the initial observations emerging from the evaluation of a small, one-year project that provided a range of opportunities for students and staff to engage with CPs, mostly using mindfulness-based approaches, at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, Scotland. The project was funded through the University’s “WISeR” (WIdening participation and Student Retention) initiative with the purpose to pilot an innovative, holistic approach to enhancing the experience of both students and staff and thereby indirectly improve retention . It was accepted from the outset that a causal link between CPs and retention could not be established through this project, but that it was reasonable to assume such a link, given what we know about CPs (see discussion above) and retention: Recent research on widening participation and retention (Thomas 2012) has indicated that up to 42 % of students consider withdrawing from their course and that “interventions and approaches to improve student retention and success should as far as possible be embedded into the mainstream provision to ensure all students participate and benefit from them.” (p. 9). The underlying factors influencing students’ decisions to continue or withdraw are complex, but students’ social and academic integration are both known to be important (e.g. Tinto 1993, in Aldossary 2008). Moreover, in Thomas’ (2012) recent summary of 22 studies examining retention in HE in the UK, she emphasised how affective dimensions of the student experience were found to be of key significance across most projects. In other words, students’ feelings about their study and about their experiences of HE are at least as important as their experiences of the cognitive dimensions of their courses. It is the affective domain that provided the rationale for piloting CPs at QMU as a creative and innovative approach likely to enhance student retention.

Methodology

Mindfulness Opportunities

The hard measure of student retention at QMU (i.e. %-age of students who have not withdrawn by the end of the year) are unlikely to be affected in the short term by any intervention, unless such an intervention is focused specifically on persuading students who have withdrawn or are indicating their intention to do so, to continue their studies. The CPs project however aimed simply to engage as many students and staff as possible, without targeting specific groups. Moreover, such quantitative measures in themselves, while providing useful data on actual withdrawal rates, were nevertheless quite meaningless to the evaluation of this project as it would be impossible to attribute changes in retention to this particular intervention. This is because the number of students withdrawing from a particular course tends to fluctuate over the years anyway, even without any specific interventions aimed at reducing withdrawal.Footnote 1 Therefore, the project aimed to make visible some aspects of the impact of CPs by focusing on student and staff self-reported experiences of the CPs. From an educational development perspective, these data at least make visible some of the value (Bamber 2013) of CPs to the lives of students and staff, in the context of learning and teaching as well as more broadly.

Thus, this was a small practice-focused project that sought to pilot various ways of implementing contemplative practices into the experience of both student and staff at QMU, with the underlying intention to enhance learning and teaching and possibly contribute to retention . The vision was to facilitate initial steps towards the integration of CPs in learning and teaching. However, as CP were unfamiliar to many students and staff, the project focused on offering opportunities to learn about and have an initial engagement with CPs, as follows:

-

1.

Generic classroom based contemplative practices led by academic staff and/or students as part of face to face lectures (see Appendix 2 for a practice example).

-

2.

Generic drop-in lunchtime mindfulness sessions, led by an external accredited mindfulness practitioner

-

3.

Generic drop-in lunchtime self-led contemplation sessions

-

4.

Presentations providing an introduction to mindfulness and a short practice session

-

5.

Some funding was provided for students and staff to attend external events related to CPs.

-

6.

Two 8-week Mindfulness Foundation Courses, one for staff and one for students, facilitated by qualified mindfulness practitioners, during the first half of Semester 2.

These were implemented as follows:

-

1.

One lecturer introduced five-minute contemplative practice sessions at the start of each lecture in one module for first year (Y1) and second year (Y2) undergraduate students, in semester 1 and for Y1 only in semester 2. The first session was facilitated by the project coordinator. Subsequent sessions were led by the lecturer, who later on encouraged students to lead these sessions themselves, which they did from week 6. Initially, the contemplation sessions involved the whole class sitting in quietness, eyes closed (optional), with the awareness being guided towards being in the present moment, through focusing on the breath (see Appendix 2). Other approaches were also used by the lecturer and the students, such as body scan (where the attention is focused on parts of the body, usually starting with the feet or the top of the head and then slowly working one’s way up or down; see e.g. Kabat-Zin 2004, Chap. 5), visualisations (where the imagination is used to create an inner landscape or event) and memory recall (going back in memory over the day, not just cognitively, but as an experience). The second lecturer started practicing mindfulness at the start of each focus session in a Masters module.

-

2.

These were lunch-time drop-in mindfulness meditation sessions led by an external expert, lasting about 35 min, with an opportunity for sharing experiences afterwards.

-

3.

These were lunch-time self-led drop-in sessions. If the coordinator was able to attend these he tended to guide the practice, using several approaches, including mindfulness, visualisation, memory recall, as well as contemplative observation.

-

4.

The presentations were given by external experts.

-

5.

A small number of places was offered to attend the Mindfulness4Scotland Conference in Edinburgh, 10 March 2013.

-

6.

The 8-week template has become the norm in mindfulness training. This was offered separately to students and staff, ran over 8 consecutive weeks, 2.5 h on the same day each week, plus a whole day Saturday retreat near the end, all held at the University, within office hours and fully funded through the project. Places were offered on a first come first served basis.

Of course, given the broad potential benefits of CPs, there is no reason to assume that any benefits obtained would be restricted to the context in which they were encountered. In other words, generic sessions might well affect learning and teaching and classroom-based sessions might well affect general well-being.

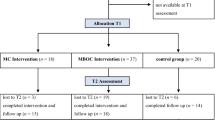

Recruitment and Participation

Staff and students were invited to participate in the drop-in sessions and to attend the presentations through messages on the QMU ‘moderator’ (i.e. emails sent to everyone with a university email address) and through posters and leaflets distributed around the University. Two of the five lecturers who expressed an interest in using contemplative practices in their teaching were briefed on the process and handed a sheet with a short outline of a possible five-minute meditation at the beginning of a lecture. Only staff already familiar with contemplative practices were encouraged to participate, whereas those interested but not currently themselves practicing any form of contemplative practice were asked to first attend the introductory and drop-in sessions. Staff intending to take part in the pilot were also asked to make sure that students were given an explanation of the rationale and approach taken, on the voluntary nature of participation (those not willing to participate could simply do something else quietly during the 5 min practice) and to ensure the practice was strictly secular. The project coordinator was asked by one member of staff to lead the first practice session for each of two groups of students and this was done.

Evaluation

Evaluation took place as follows:

-

An anonymous (2013) survey of all who attended at least one of the Introduction or drop-in sessions and left their email address and all those who had experienced in-class sessions. The total list, while variable (people were added and taken off occasionally) included around 80 student and 50 staff. An email with the request to complete an online survey was sent out in December 2012 and May 2013. Up to two reminders were sent for each. Response rates, based on these approximate numbers were therefore mostly quite reasonable, at around 20 % and 30 % respectively for Semester 1, 9 and 30 % for Semester 2.

-

Students on one of the two courses where CPs were introduced were also asked about these (anonymously) through questions inserted into the regular module evaluation questionnaires at the end of each semester (see Appendix 1).

-

Participants in the 8-week foundation courses were in addition offered a separate online evaluation survey, which asked them about the organisation of the courses as well as their experiences of engaging, with questions similar to those in the main survey.

Ethics approval was gained through the University’s research ethics committee.

Results

Evaluation of Generic In-class Sessions

These were evaluated through module evaluation forms (Semester 1: Y1 n = 30, N = 120; Y2 n = 17, N = 40; Semester 2: Y1 n = 39, N = 107), but there was also a small number (n = 7) of responses to the Semester 1 survey from students who indicated they had experienced these in-class practice sessions. There were no such responses in the Semester 2 survey.

Unfortunately, the evaluation questions in the module evaluation form were inadvertently altered in Semester 2, making it difficult to do a straight comparison (Appendix 1). Table 19.1 shows the Semester 1 results of the module evaluation forms. Only the combined results for the Y1 and Y2 student groups will be discussed here, given the small numbers.

About equal numbers of students reported to agree and disagree with the statement that they had experience of C/M (contemplation/mindfulness) prior to the semester . More students said they had engaged than not engaged (Q2). Slightly more students agreed than disagreed that C/M had helped them concentrate and focus during the class (Q3). Question four asked very explicitly about the perceived effect of C/M on academic practice and although more students indicated no effect, some indicated they had experienced an improvement in their academic practice, which is remarkable, given the very early phase of the project. Finally, there were about equal numbers of students indicating they wished to continue with the practice at the start of each class.

Judging from the module evaluations Likert-scale questions alone, overall it can be observed that there was a mixed response to the introduction of C/M but that second-year students seemed to indicate a more positive experience than first-year students.

The online survey (Semester 1) allowed a simple cross-tabulation that showed there were seven responses from students who had experienced the same in-class sessions, six of whom were first year and two of whom were eligible for Lothian Equal Access Programme for Schools funding (see LEAPS 2011). While none of these had been engaged in C/M practices before, five of the seven indicated they had found the in-class sessions helpful. Five (presumably the same students) also indicated they wished for the University to continue to provide C/M opportunities. Four of the seven indicated to have considered (“during the last three months”) leaving the University, and three responded that the C/M sessions had helped them decide to stay at QMU. While these numbers are very small, it is nevertheless encouraging that even after one semester of practice, some students said that they had found the sessions helped them decide to continue their studies, rather than withdraw. This is the only direct evidence emerging from the project to support the introduction of C/M specifically to enhance student retention .

Returning to the full response group, the comments made by students reflected this picture, but gave a little bit more insight into the dynamics of the situation. Some students reported very positive experiences:

Practicing mindfulness was great, it help[s] you get more focus in class as you feel more relax[ed] and therefore understand everything better

while others were sitting on the fence:

It hasn’t done any harm, it’s been a fun factor to the module, but it hasn’t directly improved my learning I feel

with several comments suggesting that it was because of the large group and the lack of participation by some people that it became difficult to concentrate:

Because we were so many people and not all kept quiet, it was hard to concentrate and not let the thoughts run off

Again the picture is mixed, with some students disliking the practice, while others are very positive about the experience. It is interesting that many comments from the Y1 students refer to the difficulty of engaging with the C/M sessions in a large group, as a result of others not taking it seriously and breaking the silence. The Y2 students commented on similar challenges overall, with the exception of this distraction factor, perhaps because their class was significantly smaller than the Y1 group:

Didn’t find it helpful and felt the time would have been better spent on going over the lecture and learning.

I did not enjoy the contemplation and mindfulness, although I did like using the time to prepare and read over notes.

IT WAS AN AMAZING IDEA! it makes you stop come back to your centre and help you to concentrate in what you are doing “now and here”

I personally never found it effective, but that was just my personal opinion.

I have begun using a meditation program before sleep, I feel I sleep better and feel better rested upon awakening.

Finally, there were a few comments that the C/M was too relaxing.

As indicated above, C/M sessions were not held for Y2 students in Semester 2 (because the lecturer involved was not involved in teaching these students in that semester ). Also, the evaluation forms in Semester 2 for Y1 students contained just two questions (Appendix 1). Of 107 students, 39 (36 %) completed the module evaluation form. Of these, 33 % agreed or strongly agreed that the C/M sessions should be continued with next year’s Y1 students, while 41 % disagreed. Of the 35 responses to the second question, 13 (37 %) thought the practice was a waste of lecture time. Another 13 (37 %) indicated they found the practice relaxing. Five students (14 %) said the practice helped them in some other way (e.g. “focus”, “gets me into the zone”, “insightful”). The remaining four (11 %) gave neutral responses.

Evaluation of Drop-in Lunchtime Mindfulness Sessions

Approximately 50 % of respondents had participated in one or more expert-led or self-led drop-in C/M sessions. Attendance at these sessions was not recorded consistently and quite low, with an estimated maximum of ten, minimum of none and an average of around three people. For the evaluation of these sessions, responses from the student and staff online surveys were combined, separately for each semester (n = 31 for Semester 1 (15 staff, 16 students); n = 22 for Semester 2 (15 staff, 7 students)). (It is likely that at least some of the respondents completed the survey in both semesters, therefore the responses could not be combined across semesters). Table 19.2 shows that in Semester 1, 15 people indicated to having experience of the expert-led drop-in sessions, five had experience of the self-led drop-in sessions. Fourteen people agreed that the drop-in sessions had been helpful, while one was undecided. In Semester 2, 11 people indicated to having experience of the expert-led drop-in sessions, seven had experience of the self-led drop-in sessions. Fifteen people agreed that the drop-in sessions had been helpful, six responded the question was ‘not applicable’ (it is not clear why people who participated in these session would respond with N/A, rather than ‘undecided’).

Evaluation of Presentations Introducing Mindfulness

These were attended by 18 and 14 of the respondents (Semester 1 and 2 respectively), all of whom agreed that these had been helpful.

Evaluation of C/M General Engagement and Perceived Specific Benefits

Tables 19.3 and 19.4 provide a summary of the responses to Q5 and Q7, combining the student and staff online surveys. Please note that in Semester 2, seven out of 15 staff and three out of seven student responses were from people who had attended the 8-week foundation course (see separate section below). This suggests that these respondents were very interested in C/M practices, highly committed and therefore their responses will no doubt have positively skewed the overall evaluations.

It is interesting to note that in both semesters a similar proportion of respondents indicated to have been familiar with C/M (Q5d). This may suggest that the people responding in Semester 2 were not the same respondents as in Semester 1, as otherwise one would have expected this proportion to have gone up, as a result of becoming familiar with the practices in Semester 1. It is interesting to note that the proportion of respondents indicating familiarity was about half that indicating engagement, suggesting that ‘familiarity’ could have been interpreted as having knowledge rather than experience of C/M (Q5d). There was a slight increase (by 10 %) in the proportion of respondents indicating they had engaged regularly with the C/M sessions in each Semester, as well as a slight increase (by 6 %) in the proportion who disagreed with the statement (Q5f). This is an interesting observation. Semester 2 is usually busier and more pressured than Semester 1, due to the increase in assessment load. Perhaps some respondents handled this additional pressure by increasing their engagement, while others stopped engaging as a result of it. It was particularly encouraging that the proportion of respondents indicating that they had begun using C/M as a result of the project almost doubled, while those in disagreement decreased (Q5e). Finally, there was a slight (15 %) increase in the proportion of people indicating they would like the university to continue to provide these opportunities (Q5h). All these results, while based on small numbers, are encouraging and indicative of the positive perceptions held by those who responded to the surveys. It should however be kept in mind that the respondents to the survey are self selected and probably on the whole more positive about the initiative than those who did not respond.

Question 7 in the online survey elicited responses about more specific perceived benefits of the C/M practices. Table 19.4 summarises the responses for both semesters.

As can be seen from Table 19.4 above, respondents were more in agreement with these statements in Semester 2 than in Semester 1, with the exception of Q7b. The vast majority of respondents agreed that C/M had helped them improve concentration and focus, and this proportion increased by 21 % from Semester 1 to Semester 2. In relation to academic performance, there was a slight decrease (7 %) in the proportion of respondents agreeing that this had improved, but a larger decrease in the proportion that disagreed with the same statement (15 %). In Semester 2, a larger proportion of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. In contrast, the majority of respondents agreed that C/M had helped them cope with stress, be more effective and reflective, and these proportions increased notably (15, 32, 25 %, respectively) from Semester 1 to Semester 2.

Most respondents agreed that they wished to continue with C/M practices in Semester 1, increasing to 100 % in Semester 2. Again, it should be kept in mind that these results are based on small numbers, that respondents are likely to be self-selected towards the positive end of the scale, and that some or all of the respondents in Semester 2 were also part of the respondent group in Semester 1. Nevertheless, while tentative and possibly not representative, these results are encouraging. It is interesting to observe that higher proportions of respondents agreed with statements about specific benefits (i.e. concentration and focus, coping with stress, reflection; Q7a, 7c, 7f) than generic (and perhaps less well-defined) benefits (academic performance, effectiveness, Q7b&d). Both the generic and more specific benefits can be assumed to be important to learning and all except one saw an increase in the proportion of respondents indicating their agreement.

Mindfulness4Scotland Conference Evaluation

Five staff and three students participated in this conference, which focused on the application of mindfulness in the workplace, though did not specifically include Higher Education. Feedback was received from three staff and two students, who all expressed their appreciation of having been given the opportunity to learn more about this area. They all expressed their intention to become more involved in the CPs and were impressed with the growing networks of practitioners and researchers in this area.

Evaluative Comments of the Mindfulness Practices: Students

The online surveys to students included open questions inviting respondents to comment on their experience, with the C/M practices in general (Q.5), and on their perceived effect specifically on study, work and life (Q.7). The comments were overwhelmingly positive here, indicating that for most people who took the time to write in comments, the C/M provided opportunities to de-stress, take a step back and calm down. There were, however, also some less favourable comments, indicating that not everyone managed to engage with the practice or found it helpful when they did. Perhaps a more in-depth explanation of the rationale behind introducing C/M in the classroom would be useful to students. Boxes 19.1 and 19.2 provide typical examples of student comments.

Box 19.1: Student comments to Q6: “Please say a bit more about your experience of the mindfulness and contemplation practices this semester and/or how we can further develop these opportunities.”

-

it spurred my interest

-

I did not find that it worked for me, first 10 min of class was wasted

-

I found it very helpful to relax before starting work and to clear my mind.

-

very calming before lesson and improved my concentration skills

Box 19.2: Student comments to Q8: “Please provide some more information about any positive or negative influences of the mindfulness and contemplation practice on your study, work and life.”

-

helps me to stay focused and balanced during the times of pressure.

-

I feel it has helped me reduce stress in personal and academic life. It has definitely influenced my outlook on life in a positive way. I felt less stress in the lead up to exams.

-

I would like to incorporate more into my daily life by having increased access to mindful-led classes.

-

would very much like to improve this aspect of my study, and learn how to cope better with everything in my life!

-

Practising mindfulness and contemplation has improved my life to a great extend. I am more able to cope with stress and stopped taking things personal. All together it just seems to improve life and appreciation of life

-

waste of time

Evaluative Comments of the Mindfulness Practices: Staff

These sessions had a transformative effect upon my students. Their concentration rapidly increased during the semester and their alertness and responsiveness to my questions was much stronger than in previous years and I have been lecturing for 30 years (Informal comment from lecturer).

The online surveys to staff included the same open questions as to student (see above) inviting respondents to comment on their experience with the C/M practices in general (Q.6) and on their perceived effect specifically on study, work and life (Q.8). The comments were overwhelmingly positive here also, except that there was more emphasis on the difficulties of fitting the practice into very busy work and life schedules. Boxes 19.3 and 19.4 list all the staff responses.

Taken together these responses present a very positive picture of the experiences of students and staff. The relaxation aspect was appreciated, as was the range of different opportunities. For staff, making time to engage regularly was challenging and the need for regular practice was acknowledged.

Box 19.3: Staff comments to Q6

“Please say a bit more about your experience of the mindfulness and contemplation practices this semester and/or how we can further develop these opportunities”

-

that the development of these practices will be very beneficial to staff and students at QMU

-

I led short mindfulness sessions prior to counselling classes where reflection and self awareness are really important. The students enjoyed it and want to keep going with this.

-

I totally loved it and was glad to see that the sessions continued.

-

I’m pleased that the opportunities are there to make use of personally

-

V[ery] enjoyable […] I really enjoyed the sessions which I attend as it is a different experience than doing it alone at home.

Box 19.4: Staff comments to Q8

“Please provide some more information about any positive or negative influences of the mindfulness and contemplation practice on your study, work and life.”

-

It was an interesting and enjoyable talk.

-

I find mindfulness/meditation is a helpful practice in general and contributes to a sense of inner well-being and is therefore a positive thing to do in life, but I don’t feel there is a direct relationship with the way I work or play in the rest of my life that I can specifically relate back to this practice

-

I haven’t experienced many concrete positive impacts yet but think I may have to do it more regularly!

-

It has all been very positive and has increased with increasing practice, particular useful in helping me pace my work, helped with concentration and well-being as well as reflection, which is very important for a practitioner

Evaluation of the 8-week Mindfulness Foundation Courses

Evaluations of these courses generated the most positive responses. This is not surprising, given the highly self-selected group attending them. There were 18 respondents to the 8-week course evaluation survey, with nine responses from staff and students each. Attendance was also recorded independently by the course facilitators. This is presented in Table 19.5 below. Seven staff and 11 students attended five or more sessions. Given the extreme pressure on time and that the courses were run during working hours, this was a good outcome (Table 19.5).

Respondents expressed their experiences as indicated in Table 19.6. The questions set were as much as possible identical to those in the overall survey. It is clear from the table that most respondents agreed that the course had helped them and was useful to them, with some being undecided. As the respondents all had attended 5 or more session, this group was highly self-selected, motivated and committed to engage with the C/M practices. The Table 19.6 show their combined responses to some of the questions that were also included in the overall survey.

It is particularly encouraging to note that 13 respondents indicated their interest in integrating C/M into their study or teaching, confirming that the intensive course can provide a solid basis for people’s engagement with the practices, something which is unlikely to be achieved solely through the drop-in sessions and presentations. Staff and students also commented on the perceived impact of C/M on study, work and life in general, as summarised in Box 19.5. It was of particular interest to note that these courses, besides helping directly with stress management, concentration, work and awareness, also especially provided an impetus to apply the C/M to life and to continue the practice more regularly in between sessions and following course completion.

Box 19.5. Word cloud of staff and student perceptions of C/M influence on study, work and life in general

Conclusion

This paper provides a summary of project implementation and evaluation during and after each semester in academic year 2012–2013. A range of Contemplation/Mindfulness opportunities were offered to students and staff and two lecturers participated in implementing C/M in their classes, although in-class evaluation data was only available from one. The drop-in sessions were open to all staff and students, as were the presentations, the event funding and the 8-week foundation courses. Project evaluation was done through module evaluation forms and online surveys to students and staff.

Although the project is unable to provide direct measures of the impact of C/M on retention (as discussed in the Introduction) there is strong direct evidence of its overall positive impact on the student and staff experience at QMU. Even after just one semester , student and staff responses implied positive outcomes, such as enhanced awareness, concentration and focus, as well as improved academic practice, reduced stress and increased effectiveness and reflectivity. Agreement with statements about positive effects of C/M practices generally increased from Semester 1 to Semester 2. While numbers were very small, it was also noteworthy that three out of four students who had considered leaving the university indicated that the practices had helped them decide to stay, suggesting that these practices may have a positive, indirect, effect on student retention. There was clearly some division in opinion around the in-class meditations, with several students remarking that it was a waste of lecture time, while most others indicated it was a great opportunity to relax and focus the mind.

Students’ online responses were more positive than their module evaluations, which may have been the result of self-selection, in other words, those who had a positive experience in class may have been more likely to complete the online survey. However, the overwhelming majority of respondents indicated they wished to continue the practices. An important feature emerging from the evaluation of the 8-week courses was ‘practicability’, as the course provided weekly contact with a tutor and other participants, thereby providing a motivation to take up more regular practice of C/M during the rest of the week and after course completion. Regular practice is key to harvesting the benefits of C/M and thus in that sense the 8-week courses may well be the most important aspect of this project to facilitate depth, while the other opportunities (especially the introductory presentations and the in-class sessions) were most effective in reaching larger groups of people.

It was also of interest that a number of respondents (staff and students combined) indicated to already be involved in contemplative practices or to have started to practice after being introduced to it through this project. In Semester 2 there was an increase in the proportion agreeing with the statement to this effect, as also for nearly all perceived benefits of the practices and this increase can primarily be attributed to the 8-week courses.

In conclusion several useful lessons emerge from this project in terms of engaging student learning in this non-traditional format:

-

1.

Starting a lecture with a short meditation was a new experience for students and the level of engagement could be improved by providing students with a clearer rationale for the introduction of contemplative practices in the classroom. This rationale must include a clarification of the mental activity underpinning the C/M to dispel the idea that these practices are passive or a waste of lecture time. In fact, it can be argued that C/M have always been at the core of the Academy (Altobello 2007).

-

2.

There is still a perception by many students and staff that lectures are for absorbing specific quantities of information and therefore any time taken away from the provision of information would constitute a waste of lecture time. Providing a clearer rationale as above, examples of the benefit to learning, a more gradual introduction to the practice and possibly a more subject-embedded approach could all be ways to address this perception and avoid students becoming too relaxed.

-

3.

For C/M practices to be of benefit to student learning, more staff need to be engaged, so that students are likely to encounter these practices across their entire university experience, instead of just in one or two classes. While drop-in sessions are useful, the turnout to these was generally low. Thus to capture larger numbers of staff and students, it is crucial to embed C/M into teaching, learning and course design. There is still a lot of work to be done here in terms of engaging staff across the organisation with these practices and in helping them to provide a range of different approaches, including stand-alone, in-class and subject-embedded opportunities for engagement in C/M. Developments are currently under way to offer more specific workshops on how to integrate C/M practices into learning and teaching. In addition, the 8-week courses proved an essential ingredient to the mix of opportunities, in that they particularly facilitated the development by participants of a regular C/M practice.

-

4.

A potential fruitful way forward is to adopt Rose’s quest for the deepening of reflective practices, thereby to some extent avoiding the use of the terms contemplation and meditation . However, the risk associated with this approach is that very little will change, as ‘reflection’ is already well-established with most module learning outcomes , but likely does not include the contemplative dimension. A combined approach, ‘putting contemplation back into reflection’ may well be a viable way forward.

-

5.

While relatively costly and time consuming, the intensive 8-week courses proved a great success in providing participants with a solid basis for practice. In future, we hope to be able to provide similar courses but may ask for individual financial contributions to make this sustainable and to encourage commitment to the entire course.

-

6.

There is a certain risk associated with using the terms ‘contemplation’, ‘meditation ’ and ‘mindfulness’ in that some people will be prejudiced against these practices from the very start, associating them with religious activity. It is possible that using more acceptable labels (e.g. ‘brain-based learning’; ‘teaching for deep learning’; ‘core reflection’) to attract larger numbers of people may allow a less conspicuous introduction into C/M practices.

This practice-based project has achieved significant engagement by students and staff from across the University with undoubted resulting positive experiences, thereby addressing the affective dimension of the student (and staff) experience. The potential for C/M practices to enhance the quality of University life and work for students and staff is significant and this project has made a first in-road at QMU into the employment of these practices in the classroom, to directly enhance the learning and teaching experience. The evaluation data, together with the published research and colleagues’ professional judgements (‘practice wisdom’, (Bamber 2013) provide sample evidence of the value of this educational development innovation.

As a result of this project, the University has continued the funding for the drop-in sessions, the Student Union has begun to engage with mindfulness practices as a way to improve student mental health, examples of practice have been integrated into some induction programmes and contemplative practices have begun to be integrated in module learning outcomes . To end with Albotello’s (Altobello 2007) starting quote of Tobin Hart (Hart 2004):

If we knew that particular and readily available activities would increase concentration, learning [and teaching], wellbeing, and social and emotional growth and catalyze transformative learning, we would be cheating our students [and teachers] to exclude it (my additions in square brackets).

Notes

- 1.

Retention figures for the first-year undergraduate course where CPs were introduced were identical to 2010–2011 (about 87 %) and slightly higher than 2009–2010 (82 %) and 2011–2012 (78 %).

References

Aldossary S. A study of the factors affecting student retention at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia: structural equation modelling and qualitative methods. PhD Thesis University of Stirling; 2008. Stirling: dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/691/1/saeedthesis.pdf. (Web. 27 June 2013).

Altobello R. Concentration and contemplation: a lesson in learning to learn. J Transform Educ. 2007;5(4):354–71.

Anonymous. Mindfulness: helping employees to deal with stress. Personnel Today. 2012.

Anonymous. Eric Mccollum’s mindfulness meditation course offers unique focus. US Fed News Service, Including US State News. 10 Feb 2013.

Bamber V. Evidence, chimera, belief. In: Bamber V, editor. Evidencing the value of educational development. SEDA Special 34 edn. London: SEDA; 2013. pp. 11–4.

Biggs JB, Tang C So-kum. Teaching for quality learning at university. 4th edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press; Society for Research into Higher Education; 2011.

Brady R. Learning to stop, stopping to learn: discovering the contemplative dimension in education. J Transform Educ. 2007;5(4):372–94.

Bright J, Pakorny H. Contemplative practices in higher education: breathing heart and mindfulness into the staff and student experience. Educ Dev. 2012;13(3):22–3.

Chaskelston M. Mindfulness in the workplace. Presentation at the mindfulness4Scotland conference, Surgeons Hall, Edinburgh. Mindfulness4Scotland; 2013.

Claxton G. Thinking at the edge: developing soft creativity. Camb J Educ. 2006;36(3):351–62.

Craft A. Fostering creativity with wisdom. Camb J Educ. 2006;36(3):337–50.

de Mello A. Awareness. Grand rapids. Michigan: Zondervan; 1990.

Halliwell, editor. Mindfulness Report; 2009.

Hart T. Opening the contemplative mind in the classroom. J Transform Educ. 2004;2(1):28–46.

Kabat-Zin J. Full catastrophe living: how to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulnessmeditation. London: Piatkus; 2009.

Oberski I. Supporting and developing the curriculum by putting contemplation back in HE: enhancing students’ attention and effectiveness. Enhancement Themes Newletter. 2012. pp. 4–5, http:/tiny.cc/ETNews. (Web. 30 Aug 2014).

Langer EJ. The power of mindful learning. Cambridge: Lifelong Books/Da Capo Press; 1997.

Palmer P, Zajonc A. The heart of higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Paul G, Barb E, Steven JV. A longitudinal study of students’ perceptions of using deep breathing meditation to reduce testing stresses. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):287–92.

Ramsburg JT, Youmans RJ. Meditation in the higher-education classroom: meditation training improves student knowledge retention during lectures. Mindfulness. 2013;5(4):431–41.

Rose E. On reflection: an essay on technology, education, and the status of thought in the twenty-first century. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press Inc.; 2013.

Sedlmeier P, et al. The psychological effects of meditation: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(6):1139–71.

Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Astin JA. Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: a review of research. Teach Coll Rec. 2011;113(3):493–528.

Sillito D. Scans ‘show Mindfulness Meditation Brain Boost’. Dir. Sillito, D. BBC; 2012.

Thomas L. Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation; 2012.

Wang X, et al. An exploration of Biggs’ constructive alignment in course design and its impact on students’ learning approaches. Assess Eval High Educ. 2013;38(4):477–91.

Williams JMG, et al. The mindful way through depression. London: Guilford Press; 2007.

Zaretsky R. An appeal for silence in the seminar room. Times Higher Education. 8 August 2013.

Acknowledgements

The following people have made contributions to this project by offering their time, participation, ideas and critically constructive comments: Avinash Bansode, Carolyn Choudhary, Hillary Glendinning, Karen Goodall, Michele Hipwell, Judith Lane, Jane McKenzie. Wendy Stewart.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1 Evaluation Questions for In-class Practice

The following questions were used with a Likert scale (Strongly Agree-Agree-Neither Agree or Disagree-Disagree-Strongly Disagree-Not Applicable) for the in-class practice. There was also one open question (Q.6) to provide students with an opportunity to comment freely on their experience

Semester 1:

-

1.

Prior to this semester , I had experience of contemplation/mindfulness.

-

2.

I regularly engaged with the mindfulness/contemplation programme this term.

-

3.

The mindfulness/contemplation practice was useful in helping me improve my concentration and focus during each class session.

-

4.

As a result of practicing mindfulness/contemplation I believe my academic performance improved.

-

5.

I wish to continue practicing mindfulness/contemplation at the start of each class session.

-

6.

Please share any other thoughts and feelings regarding mindfulness contemplation practice this semester .

Semester 2:

-

1.

I believe that the brief Mindfulness practice should be continued next year at the beginning of the lecture for the first year students.

-

2.

Please provide your opinion in the form of an adjective (great, rubbish, brilliant, time wasting, relaxing, etc.) to describe the benefits you did or did not receive from the Mindfulness practice this semester .

Appendix 2 Example Practice

Contemplative Practice and Mindfulness in Higher Education

Meditation in 7 steps:

-

1.

Be comfortable in body & mind. Sit in an upright chair, your back well supported. Feet flat on the floor (you could take off your shoes). Head easily balanced on top of your spine. Hands palms-up in your lap, one palm on top of the other, or palms down, on your knees. Arms relaxed by your sides

-

2.

Deep breaths: Take three deep breaths in and out, as deep as is comfortable, without straining. Do this in your own rhythm

-

3.

Centre yourself mentally: Become aware of the feelings of your body on the chair, your feet on the floor. Then become aware of the sounds around you, any smells, the feeling of the air on your skin, and of your clothes on your skin. Close your eyes if they are still open.

-

4.

Bring your attention to your breathing: Focus on the feeling and sound of your breathing. Remain still and feel the gentle in-and outflow of your breath. Feel it in your ribcage/chest, your abdomen, shoulders, and nostrils.

-

5.

Return to the breath: Usually, after some time, a sound or a memory, a feeling or emotion will carry your attention with it. You may be caught up into this flow for just a few seconds or much longer. At some point you will realise what has happened. When you do, just return your attention to your breathing as in step 4. Keep going through step 4 and 5 during the meditation as needed.

-

6.

Return to the here an now: Once the time is up, bring your attention back to the sensations of your body on the chair and feet on the floor. Become aware of the sounds and the feeling of the air on your skin. Become aware of the people in the room and bring yourself solidly back to the here and the now.

-

7.

Resume regular activity: Gently open your eyes. Take a few minutes to re-adjust to where you are. Smile. Drink a glass of water. If you want, write a journal entry. Then resume your activities as usual.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Oberski, I., Murray, S., Goldblatt, J., DePlacido, C. (2015). Contemplation & Mindfulness in Higher Education. In: Layne, P., Lake, P. (eds) Global Innovation of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Professional Learning and Development in Schools and Higher Education, vol 11. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10482-9_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10482-9_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-10481-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-10482-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)