Abstract

There is widespread concern in Australia and internationally at the high prevalence of psychotropic medication use in residential aged care facilities. It is difficult for nurses and general practitioners in aged care facilities to cease new residents’ psychotropic medications when they often have no information about why residents were started on the treatment, when and by whom and with what result. Most existing interventions have had a limited and temporary effect and there is a need to test different strategies to overcome the structural and practical barriers to psychotropic medication cessation or deprescribing. In this chapter, we review the literature regarding psychotropic medication deprescribing in aged care facilities and present the protocol of a novel study that will examine the potential role of family members in facilitating deprescribing. This project will help determine if family members can contribute information that will prove useful to clinicians and thereby overcome one of the barriers to deprescribing medications whose harmful effects often outweigh their benefits. We wish to understand the knowledge and attitudes of family members regarding the prescribing and deprescribing of psychotropic medications to newly admitted residents of aged care facilities with a view to developing and testing a range of clinical interventions that will result in better, safer prescribing practices.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

8.1 Introduction

On 30 June 2012, there were 166,976 Australians living permanently in residential aged care facilities, 52.1 % of whom suffered from dementia [1]. About a half of the residents of aged care facilities take one or more psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines) [2–4]. For some, they are a worthwhile adjunct to psychosocial approaches in the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). For others, however, psychotropic medications no longer serve a useful purpose. Unnecessary medications are a major concern. They are costly and have adverse effects that are distressing and reduce the quality of life of older people [5]. Residential aged care facilities are complex organisations and seemingly simple tasks—namely reducing residents’ medications—can present real challenges in this environment.

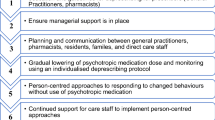

“Deprescribing” is a term that has been coined to describe the potentially complicated process of optimising medication regimens through reduction and/or discontinuation of inappropriate medications [6–10]. Deprescribing should ideally be a patient-centred process involving multidisciplinary collaboration. Engagement of general medical practitioners (GPs) is essential and pharmacists can play a key coordinating role [11–13]. Steps involved in deprescribing include review of all medications; identification of potentially inappropriate medications that could be ceased, replaced or reduced; prioritisation of the order in which medication changes should occur; planning of the deprescribing regimen together with patients and carers and provision of continuous monitoring, review and support in a manner analogous to medication prescribing [11, 14–17]. In undertaking deprescribing, it is important to acknowledge that there are patients who may continue to derive benefits from medications on an ongoing basis. Therefore, the goal of deprescribing should relate more to quality use of medications rather than cessation as an end in itself.

In this chapter, we first review the literature regarding psychotropic medication deprescribing among aged care facility residents, including the barriers to deprescribing and the limitations of current approaches. We then present the protocol of a novel study that will examine the potential role of family members in facilitating deprescribing by filling in gaps in clinicians’ knowledge of residents’ psychotropic medication histories.

8.2 Psychotropic Medication Use in Residential Aged Care Facilities

Residential aged care facility residents are prescribed large quantities of antipsychotic and other psychotropic medications. In a recent study in Sydney, Australia, for example, 28 % of nursing home residents were prescribed an antipsychotic medication, 27 % took an antidepressant and 16 % took an anxiolytic or hypnotic [3]. These rates were actually higher than those reported by the same authors nearly 15 years earlier. Similar prescribing practices apply in the USA, the UK, Europe and Scandinavia [3].

Antipsychotic and antidepressant medications can alleviate distress in the case of residents with persistent, troubling psychotic symptoms, aggressive behaviours or melancholic depression but the numbers of residents with these sorts of syndromes are relatively modest and such high prescribing rates cannot be justified clinically [18].

All medications have unwanted, adverse effects. Psychotropic medications increase the risk of sedation, confusion, falls, fractures and loss of mobility and independence [19, 20]. They can also lead to nausea, dizziness and other unpleasant side effects. Antipsychotic medications in particular are associated with increased mortality in people with dementia and all second generation antipsychotics now carry a package warning to that effect [21]. Quantifying the positive and negative effects of these treatments in frail older people is difficult as most drug studies exclude aged care facility residents. On balance, however, it is probable that more residents of these facilities are harmed than helped by them. The broader community is disadvantaged too as some newer medications are expensive and falls with fractures lead to costly hospital admissions and increased care needs.

8.3 Principles and Practice of Deprescribing Psychotropic Medications

Deprescribing aged care facility residents’ psychotropic medications is now widely recommended. Most published clinical guidelines state that antipsychotics should be withdrawn at least every 6 months on the grounds that even if the medication played a useful role when instituted (which is debatable), the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia usually remit with time, making long-term treatment unnecessary [22]. This advice is supported by evidence. In a recent Cochrane review of nine de-prescribing studies involving 606 people with dementia, most were withdrawn safely from long-term antipsychotics without any detrimental effects. Caution is required though. There were suggestions in two of the nine reports that people whose agitation or psychosis had clearly improved with treatment were more likely to relapse when their treatment was stopped [23].

Despite widespread concern in professional and public domains, psychotropic medications are mostly continued for long term. In the only study of its type to date, we found in a longitudinal survey of seven aged care facilities in Melbourne, Australia, that medications were rarely changed or stopped. Contrary to expectation, most medications had been initiated prior to entry to the facility. Nearly one-third (27 %) of residents were taking an antipsychotic at the time of admission. Over the following 6 months, antipsychotics were started in another 5 % and stopped in 5 % of cases. Similarly, antidepressants were taken by 30 % of residents at entry point. They were started in another 6 % and stopped in only 5 % over a 6-month period [24]. A recent study using the National Prescription Database in Ireland also reported high rates of psychotropic medication use on admission to residential aged care. However, continuation of psychotropic medications following admission only partially explained the higher dispensing rates of psychotropic medications in aged care facilities [25].

8.4 Barriers to Deprescribing Psychotropic Medications

Managing medications initiated prior to aged care facility admission presents a real challenge. Most high-level care residents have moderate-to-severe dementia and cannot recall who started a treatment, let alone its rationale, duration or clinical benefit if any. The documentation that accompanies new arrivals is often sketchy and former GPs are rarely contacted for information. Current GPs might therefore feel reluctant to withdraw existing treatments. They have no knowledge of residents’ former level of function and the adverse effects of medications may not be obvious. Furthermore, GPs and facility nursing staff may fear that “difficult” behaviours will re-emerge [26]. Deprescribing guidelines acknowledge that treatment optimisation requires knowledge of patients’ medical and functional histories, medication histories and treatment response [27]. As things stand, GPs attending Australian residential aged care facilities will rarely have access to all this information, making it difficult for them to comply with the department of Health and Ageing guiding principles for medication management in aged care facilities [28].

To complicate matters, there are practical, systemic and cultural barriers to implementing change in organisations as complex as residential aged care facilities in which the responsibility for initiating, monitoring and adjusting treatments is dispersed across a range of personnel from a variety of professional backgrounds (although only a medical or nursing practitioner can actually change medications). These barriers can include regulatory arrangements, reimbursement systems, leadership style, structural influences (facility size, staff turnover, educational opportunities) and overt and latent shared norms [29].

8.5 Existing Approaches to Deprescribing Psychotropic Medications and Their Limitations

The approaches used to date to encourage de-prescribing have entailed legal compulsion, multi-disciplinary reviews and educational programs. Statutory directives have minimal effect. In the USA, federal regulations introduced in 1990 to limit antipsychotic medications to nursing home residents with specific psychiatric diagnoses and behavioural indications led to a reduction in psychotropic prescriptions—but only to the levels seen currently in Australia [30]. In New South Wales, Australia, a legal requirement to seek substitute consent before administering psychotropic medications to people who cannot give consent themselves is mostly ignored [31]. Legal sanctions that are not monitored or enforced are unlikely to be of value in changing practice.

Medication reviews by a geriatrician, pharmacist, nurse and GP proved more effective in a South Australian controlled trial involving 154 aged care facility residents with either a challenging behaviour or polypharmacy. Scores on a scale of medication appropriateness were significantly reduced in the intervention facilities, with no consequent worsening of behaviours [32]. Similar findings emerged in four other studies of pharmacist or multidisciplinary reviews of psychotropic prescriptions in Australian, British and Swedish long-term care facilities [33].

Educational initiatives have proved successful in most but not all trials [33]. In Queensland, Australia, pharmacist-led medication reviews coupled with nursing education led to reductions of 6 and 14 % in benzodiazepine and antipsychotic prescriptions, respectively. There were no differences, though, in residents’ disability levels or hospital admissions over coming months [34]. Outreach visits by pharmacists were well received but had no discernable effects in a South Australian study [35]. By contrast, in Tasmania, Australia, a complex intervention in which community pharmacists initiated medication audits, feedback cycles, nursing education sessions and a multi-disciplinary conference led to cessations or reductions in doses for 37 % of residents taking an antipsychotic in intervention facilities compared with 21 % in control facilities. For residents taking a benzodiazepine, there were cessations or reductions in dose for 40 and 18 % of those in intervention and control facilities, respectively [36]. When prescriptions were checked a year later, benzodiazepine usage had dropped a little further in intervention facilities but the proportions of residents taking antipsychotics had returned to baseline levels [37].

8.6 Study Protocol

8.6.1 Study Rationale

Educationally directed efforts to induce deprescribing and maintain changes in practice may be too complex, time consuming and expensive to contemplate rolling out nationally without additional strategies in place to reinforce them. With this in mind, we wish to explore a new and complementary approach that taps family members’ knowledge of residents’ prescribing histories and their willingness to endorse deprescribing when provided with balanced information about this practice. Our study proposal is based on the following propositions:

-

1.

It is understandable that clinicians are reluctant to stop a treatment when they have no knowledge of who started the treatment, their reasons for starting it and its benefits and adverse effects.

-

2.

There are no simple, familiar clinical markers to guide psychotropic de-prescribing. If an antihypertensive or hypoglycaemic medication is stopped, residents’ blood pressures or glucose levels can be monitored easily and treatments can be re-started if required. In the case of psychotropic medications, staff must accept a risk that psychiatric disorders or challenging behaviours of an unknown nature may re-emerge for at least a proportion of residents at some point.

-

3.

In the case of residents with dementia who cannot provide this sort of information themselves, tracing information through former GPs, medical specialists and pharmacists is difficult, time consuming and not remunerable for GPs—though perhaps not impossible. This approach will form the basis of a separate future research initiative.

We are not proposing any particular intervention based on family members’ responses. Instead, we wish to adopt a phased step-wise approach that has been recommended for evaluation of complex interventions [38]. This will involve first checking, by means of a modestly sized feasibility study, if family members’ knowledge of psychotropic prescriptions and their attitudes to deprescribing have the potential to make a useful contribution to clinical practice. It is envisaged that this information will, in turn, inform the development of a definitive intervention that utilises the facilitators and addresses the barriers that have been identified in the feasibility study.

8.6.2 Research Questions

In an effort to circumvent the difficulties encountered in deprescribing psychotropic medications in aged care facilities, our project will address the following questions:

-

1.

For aged care facility residents who take one or more psychotropic medications at the point of entry to high-level care, to what extent do family members know that these medications are being dispensed and can they recognise their names?

-

2.

To what extent can family members provide information about the original prescriber of each medication; the original indication(s) for its use; the approximate duration of the prescription and their perception of its effectiveness?

-

3.

If family members are given carefully balanced, evidence-based written information about the advantages and disadvantages of the relevant classes of medications, what views do they express about the pros and cons of continuing prescriptions and would they support efforts by the nursing staff and GP to attempt deprescribing?

-

4.

What are family members’ attitudes towards deprescribing, as indicated by their scores on an adapted version of the Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (PATD) Questionnaire (see description below)?

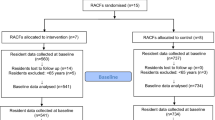

8.6.3 Study Design

We propose an exploratory study (using surveys and semi-structured interviews) of the knowledge and attitudes of family members concerning ongoing psychotropic prescriptions for 50 newly admitted high care residents of a convenience sample of aged care facilities in south-eastern Melbourne.

8.6.4 Study Procedures

Family members who agree to participate and provide written informed consent will be encouraged to seek information from other sources regarding their relative’s medication history and to complete a semi-structured interview (of approximately 1-h duration) with a trained research assistant at a later time. This will take place either in person, in a private area of the aged care facility, or by telephone if preferred. Face to face interviews will be audiotaped for checking purposes if respondents agree. Other family members will be welcome to participate if they wish. It will be made clear prior to the interview that we are seeking family members’ views purely for research purposes and that the research assistant (who will have no specialist knowledge in this area) will not be able to engage in discussion about individual medications.

The research assistant will present the family members with a list obtained from the aged care facility of all current regularly prescribed medications and all occasionally prescribed medications that have been dispensed at least once in the previous week. The list will include the medications’ generic and all Australian brand names. The family members will be asked: (1) to nominate which medication names they recognise as the ones being taken by their relative (answers will be recorded as “recognised” or “not recognised”); (2) if they know the name and identity (GP, specialist) of the original prescriber of each medication; (3) the reason(s) why each medication is prescribed; (4) the approximate duration of each medication prescription and (5) their rating of each medication’s effectiveness on a 5-point scale (ranging from “very effective” to “very ineffective”, or “don’t know”). Responses will be recorded verbatim.

Next, family members will be presented with a short pamphlet (about 250 words) outlining the general benefits and risks of ongoing prescriptions of psychotropic medications and the principles of deprescribing. The pamphlet will state that, while some medications are required on a continuing basis, many no longer serve a useful purpose and are best stopped gradually, usually over a period of several weeks, to reduce side effects and costs. It will be made clear that medications can be started again if necessary. After a discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of deprescribing in general, using pre-prepared probes if necessary, respondents will be asked to rate their level of support for attempts to deprescribe each psychotropic medication on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly support” to “strongly oppose” (or “don’t know”).

Finally, GPs will be given a list of all the psychotropic medications (with doses) being dispensed regularly to their patients and asked to nominate if any are used primarily for physical health reasons (e.g. antidepressants to treat pain or urinary incontinence).

8.6.5 Ethical Considerations

This study has been submitted for approval to the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

This is a feasibility study, not a deprescribing initiative, and we do not expect medication deprescribing to occur on a large scale as a result of study participation. However, the information provided by family members could be of genuine clinical value and so, with their consent, we will pass this information on to the aged care facility nursing staff and GPs using a specially designed form. Furthermore, following their involvement in the study, family members may find themselves wondering whether review and adjustment of their relatives’ psychotropic medications are needed. As a result, there may be more medication reviews, and more family requests for reviews, than would normally be the case, a possibility that facilities will be made aware of. Any such reviews would take place separate to the study, as part of residents’ routine clinical care. GPs attending study facilities will be informed of the study and given the opportunity to opt out of it at any time. If they do so, we will not recruit family members of any of their patients (or cease further recruitment if GPs opt out of the study after recruitment has already commenced).

Although this possible increase in medication reviews may place additional demands on facility and GP resources, it may also contribute positively to improved patient care. If GPs choose to make medication changes, one possible benefit may be the finding that residents no longer require certain medications, or only require the medications at lower doses.

On the other hand, reducing or ceasing psychotropic medication may be associated with a risk of re-emergence or worsening of previously well-treated behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. In this event, it may be appropriate to reinstate medication (that was reduced or ceased) to help re-settle these symptoms, in conjunction with utilising non-medication approaches to treatment. The researchers will be available to provide initial advice to the aged care facility and GPs if such a scenario arises. If direct specialist involvement is required to assist GPs in this process, guidance will be provided on how to refer residents to the local public Aged Persons Mental Health Service (which will have been given prior notice regarding the conduct of the study).

8.6.6 Setting

We will include the family members of between 2 and 5 residents from 10 to 25 aged care facilities in south-eastern Melbourne, giving a total of 50 residents. We will sample facilities broadly to ensure a mix of public and private facilities across a range of suburbs.

8.6.7 Recruitment

Because the residents concerned will have dementia, they will be unlikely to be able to give informed consent to the study. Instead, we will seek consent from their closest family member or legal guardian. This will be done in accordance with the ethical principles for involving people with cognitive impairment in research studies that are outlined in the Australian National Statement for Ethical Conduct in Human Research [39]. Family members of residents who meet the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria (see below), and are therefore eligible for study participation, will be identified by facility administrators and their contact details passed on to us with their verbal consent. The research team will subsequently contact the family members directly to describe the project and answer any questions. An explanatory statement for family members to read and a consent form for them to sign and return will subsequently be posted. Consent will be sought separately for the interview to be tape-recorded and for the information provided about psychotropic medications to be fed back to the nursing staff and GP.

8.6.8 Participants

8.6.8.1 Inclusion Criteria

We will include family members of residents who (1) have been admitted or transferred from another facility to high level care within the previous 3 months; (2) have a diagnosis of dementia entered in the clinical file and/or have a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≤23 points; (3) continue to take one or more previously prescribed antipsychotic, antidepressant and/or benzodiazepine medications and (4) have a nominated primary contact person (usually a family member) who has sufficient English fluency to complete an interview.

8.6.8.2 Exclusion Criteria

We will exclude family members of residents who (1) have a diagnosis entered in the clinical file of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder or (2) are judged by nursing staff to be so physically unwell that death is imminent.

8.6.9 Outcome Measures

8.6.9.1 Primary Measure

The primary measures of interest will be the proportions of family members who (1) can recognise the name(s) of the psychotropic medications dispensed to their relative and (2) can nominate the original prescriber of each medication, the original reason(s) for the prescription, the approximate duration of the prescription and their perception of its effectiveness.

8.6.9.2 Secondary Measures

The secondary measures of outcome will be (1) family members’ attitudes to the deprescribing of these medications and (2) their scores on an adapted version of the Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (PATD) Questionnaire, a 15-item checklist developed in South Australia [8, 9]. This questionnaire—which has items like “I believe that all my medications are necessary”—has demonstrated content validity, construct validity and test-retest reliability. The authors of this tool have consented to its adaptation for use among family members of aged care facility residents.

8.6.10 Sample Size Justification

We anticipate that 50 interviews will be sufficient to capture a broad range of viewpoints concerning the major psychotropic classes. If we reach the point of data saturation, a smaller number of interviews may be required.

8.6.11 Feasibility

We have partnered with aged care providers to conduct many studies in local aged care facilities over a 20-year period. This research will build on established networks. The residential standards agency regards participation in research very favourably and so facilities derive direct and indirect benefits from collaborating with us. This particular project requires little staff input and presents no major resource issues for the participating aged care providers. The study will be conducted in accordance with Alzheimer’s Australia guidelines for involving people living with dementia and their families in research [40]. This will help ensure that the study is both feasible and acceptable from a consumer and carer perspective.

One of the objectives of the study is to gauge family members’ motivation to participate in such an exercise and their capacity to contribute useful information. We believe that many will find the topic of interest and so completion rates are likely to be high.

8.6.12 Statistical Analysis

8.6.12.1 Quantitative Analysis

The proportions of family members who recognise prescribed treatments will be tabulated by medication class (antipsychotic, antidepressant and benzodiazepine or other hypnotics) and compared with other selected major medication classes (e.g. antihypertensives).

The proportions of family members who can nominate the original prescriber (yes/no), indication (known/unknown) and ratings of the perceived effectiveness of treatments will be tabulated by medication class.

Comparisons between psychotropic classes, and between psychotropic and other classes, will be made using chi-square and t-tests for categorical and continuously distributed data, respectively.

8.6.12.2 Qualitative Analysis

Family members’ comments to the semi-structured probes will be noted manually on a prepared template. Major themes will be extracted from these notes using a framework analysis method [41]. Responses will then be coded by two research staff independently followed by discussion and reconciliation of any disagreements. Thematic analysis will address attitudes towards deprescribing with special reference to positive and negative concerns, perceived barriers and facilitators, preferred processes and expressed needs for additional information, communication or support.

8.7 Discussion

If it emerges that few family members can have any useful information to add, and few of them have any views about prescribing practices, there may be no value in seeking their participation in the complex decision-making processes that deprescribing entails. Based on experience, however, we suspect that family members will often have useful knowledge and/or clear views about their relatives’ ongoing pharmacotherapy. If this is true, there may be opportunities to include their knowledge and attitudes in the residential assessment procedures mandated by the Australian federal government.

If it transpires that most family members do not want psychotropic medications to be stopped, then efforts to encourage nurses and GPs to deprescribe them, without reference to relatives’ views, will almost certainly prove counterproductive and a different strategy will be required.

The prescribing histories reported by family members will sometimes be incorrect but, to put this in context, errors can arise even when information is taken from competent patients or medical records [42]. Medical practitioners and pharmacists must always consider the possibility of error when reviewing prescriptions with patients or their proxies and the possibility of error is not in itself a reason to persist with a treatment, regardless of other considerations.

In conclusion, this pilot study will address one of many structural barriers to deprescribing (in this case, a lack of valid clinical data regarding psychotropic prescriptions). Multiple strategies might need to be adopted to change practice in real-world conditions and so this study is one of a suite of projects that we will attempt to implement in an effort to improve psychotropic prescribing practices in residential aged care settings. Development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for psychotropic medication deprescribing in aged care facilities is an anticipated longer term goal.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2013) Residential aged care and aged care packages in the community 2011–12 [Online]. http://www.aihw.gov.au/aged-care/residential-and-community-2011-12/. Accessed 11 Feb 2014

Hosia-Randell H, Pitkala K (2005) Use of psychotropic drugs in elderly nursing home residents with and without dementia in Helsinki, Finland. Drugs Aging 22(9):793–800

Snowdon J, Galanos D, Vaswani D (2011) Patterns of psychotropic medication use in nursing homes: surveys in Sydney, allowing comparisons over time and between countries. Int Psychogeriatr 23(9):1520–1525

Rattinger GB, Burcu M, Dutcher SK, Chhabra PT, Rosenberg PB, Simoni-Wastila L et al (2013) Pharmacotherapeutic management of dementia across settings of care. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(5):723–733

Wood-Mitchell A, James IA, Waterworth A, Swann A, Ballard C (2008) Factors influencing the prescribing of medications by old age psychiatrists for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a qualitative study. Age Ageing 37(5):547–552

Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts MS (2009) Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 26(12):1013–1028

Brulhart MI, Wermeille JP (2011) Multidisciplinary medication review: evaluation of a pharmaceutical care model for nursing homes. Int J Clin Pharm 33(3):549–557

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD (2013) Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm 35(1):51–56

Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S (2013) People’s attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribe. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(9):1508–1514

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD (2013) Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 30(10):793–807

Woodward M (2003) Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res 33(4):323–328

Alexander GC, Sayla MA, Holmes HM, Sachs GA (2006) Prioritizing and stopping prescription medicines. CMAJ 174(8):1083–1084

Ostini R, Hegney D, Jackson C, Williamson M, Mackson JM, Gurman K et al (2009) Systematic review of interventions to improve prescribing. Ann Pharmacother 43(3):502–513

Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, Maio V, Handler SM, Pauker SG (2008) Discontinuing medications: a novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(10):1946–1952

Le Couteur D, Banks E, Gnjidic D, McLachlan A (2011) Deprescribing. Aust Prescr 34:182–185

Ostini R, Hegney D, Jackson C, Tett SE (2012) Knowing how to stop: ceasing prescribing when the medicine is no longer required. J Manag Care Pharm 18(1):68–72

Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA (2012) Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. Am J Med 125(6):529–537e4

Draper B, Brodaty H, Low LF (2006) A tiered model of psychogeriatric service delivery: an evidence-based approach. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 21(7):645–653

Hartikainen S, Lonnroos E, Louhivuori K (2007) Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62(10):1172–1181

Taipale HT, Bell JS, Gnjidic D, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S (2012) Sedative load among community-dwelling people aged 75 years or older: association with balance and mobility. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32(2):218–224

Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Brookhart A, Dormuth C, Wang PS (2007) Risk of death associated with the use of conventional versus atypical antipsychotic drugs among elderly patients. CMAJ 176(5):627–632

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (2009) Practice Guideline 10: Antipsychotic medications as a treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia [Online]. https://www.ranzcp.org/Resources/Statements-Guidelines/Practice-Guidelines.aspx. Accessed 09 Feb 2014

Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, Vander Stichele R, De Sutter AI, van Driel ML et al (2013) Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD007726

O’Connor DW, Griffith J, McSweeney K (2010) Changes to psychotropic medications in the six months after admission to nursing homes in Melbourne, Australia. Int Psychogeriatr 22(7):1149–1153

Maguire A, Hughes C, Cardwell C, O’Reilly D (2013) Psychotropic medications and the transition into care: a national data linkage study. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(2):215–221

Azermai M, Vander Stichele RRH, Van Bortel LM, Elseviers MM (2013) Barriers to antipsychotic discontinuation in nursing homes: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health 18:346–353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.832732

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG (2012) Thinking through the medication list—appropriate prescribing and deprescribing in robust and frail older patients. Aust Fam Physician 41(12):924–928

The Department of Health (2012) Guiding principles for medication management in residential aged care facilities [Online]. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/nmp-pdf-resguide-cnt.htm Accessed 09 Feb 2014

Tjia J, Gurwitz JH, Briesacher BA (2012) Challenge of changing nursing home prescribing culture. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 10(1):37–46

Rovner BW, Edelman BA, Cox MP, Shmuely Y (1992) The impact of antipsychotic drug regulations on psychotropic prescribing practices in nursing homes. Am J Psychiatry 149(10):1390–1392

Rendina N, Brodaty H, Draper B, Peisah C, Brugue E (2009) Substitute consent for nursing home residents prescribed psychotropic medication. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(3):226–231

Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, Giles L, Birks R, Williams H et al (2004) An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing 33(6):612–617

Nishtala PS, McLachlan AJ, Bell JS, Chen TF (2008) Psychotropic prescribing in long-term care facilities: impact of medication reviews and educational interventions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16(8):621–632

Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, Lynne TA, Purdie DM, Glasziou PP et al (2001) Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 51(3):257–265

Crotty M, Whitehead C, Rowett D, Halbert J, Weller D, Finucane P et al (2004) An outreach intervention to implement evidence based practice in residential care: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN67855475]. BMC Health Serv Res 4(1):6

Westbury J, Jackson S, Gee P, Peterson G (2010) An effective approach to decrease antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes: the RedUSe project. Int Psychogeriatr 22(1):26–36

Westbury J, Tichelaar L, Peterson G, Gee P, Jackson S (2011) A 12-month follow-up study of “RedUSe”: a trial aimed at reducing antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr 23(8):1260–1269

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F et al (2007) Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 334(7591):455–459

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National statement on ethical conduct in human research (2007) - Updated December 2013 [Online]. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/e72. Accessed 09 Feb 2014

Alzheimer's Australia (2013) Participate in research [Online]. http://www.fightdementia.org.au/research-publications/clinical-trials--research-projects.aspx. Accessed 09 Feb 2014

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:117

Cumbler E, Wald H, Kutner J (2010) Lack of patient knowledge regarding hospital medications. J Hosp Med 5(2):83–86

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded by the Lions John Cockayne Memorial Fellowship Trust Fund.

The Lions John Cockayne Memorial Fellowship Trust is jointly funded by Oakleigh Lions Club Elderly Peoples Home Inc. and Monash Health.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest and are alone responsible for the content and writing of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Plakiotis, C., Bell, J.S., Jeon, YH., Pond, D., O’Connor, D.W. (2015). Deprescribing Psychotropic Medications in Aged Care Facilities: The Potential Role of Family Members. In: Vlamos, P., Alexiou, A. (eds) GeNeDis 2014. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 821. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08939-3_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08939-3_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08938-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08939-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)