Abstract

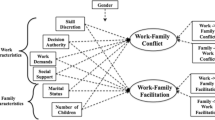

Guilt arising from attempting to balance work and family has been a frequent topic of interest in the media and the organizational behavior literature. Despite this, until recently, research on work-family guilt (WFG) was limited. This chapter reviews the qualitative and quantitative empirical evidence pertaining to the intersection of gender and WFG. It begins by defining WFG and discussing issues of measurement, including measurement equivalence for gender. The antecedents and outcomes of WFG are discussed, as are inter-relationships between work-to-family guilt, family-to-work guilt and work-family conflict and facilitation. Subsequently, the chapter reviews how WFG and its antecedents and consequences in the work and family domains relate to various aspects of gender. These include differences due to biological gender (i.e., whether someone is a man or a woman), gender-role orientation (i.e., instrumental/ expressive personality characteristics), gender-role attitudes (i.e., traditional/egalitarian), gender-role values, and gender-role behaviors. The chapter also examines the role of culture as a moderating variable, and concludes with a critique of the literature and a discussion of implications for theory, research and practice.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Problem

I always feel as though I am failing in some way, as though I am cheating my children, my husband, and myself. The guilt is very difficult to deal with. (McElwain 2008)

As this quote from a working mother illustrates, work–family (W–F) guilt is not only pervasive, but it can also be extremely detrimental to the well-being of workers and their families. As illustrated by the following quote, there is a common perception that women are more likely to suffer from W–F guilt than men.

I do think men and women experience guilt differently. I believe…women feel more guilt about the work/family balance—perhaps it’s innate…perhaps it’s because of the traditional roles men and women have had in the home. I know my husband is sad that he doesn’t get to spend as much time with his family as he would like, but I don’t think he struggles with the same degree of guilt. (McElwain 2008)

Guilt arising from attempting to balance work and family has been a frequent topic of interest in the media and popular press (Bort et al. 2005; Chapman 1987), as well as in the organizational behavior literature. Despite this, until recently, research on W–F guilt has been very limited (Seagram and Daniluk 2002). In this chapter, I review the empirical evidence pertaining to the intersection of gender and W–F guilt.

2 Definition and Conceptualizations of W–F Guilt

Most theory and research on guilt has focused on guilt in general rather than on guilt as it applies specifically to the W–F interface. In the general guilt literature, guilt is viewed as a negative emotion that arises when individuals violate their internalized standards about what constitutes proper behavior (Kubany 1994). Thus, when individuals believe they should have thought, felt, or acted differently, it can result in feelings of guilt (Kubany 1994; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1990). Guilt has been conceptualized as consisting of a cognitive component, which consists of the recognition that one has harmed another; an affective component, which refers to the unpleasant feelings that are experienced; and a motivational component, which is the desire to undo the harm that has been caused (Hoffman 1982). Kubany et al. (1996) propose that more guilt will be experienced to the extent that individuals act in a way that violates their values, feel their actions are unjustified, feel responsible for what happened, and/or believe that they could have foreseen and prevented the outcome.

Many different definitions of W–F guilt can be found in the literature (McElwain and Korabik 2004). Most of them emphasize one or more of the aspects of general guilt discussed above. Thus, W–F guilt is often seen as resulting from having to make a choice between work and family (Conlin 2000; Pollock 1997), allowing work to interfere with family life (Glavin et al. 2011), or failing to adequately balance work and family roles (Napholz 2000). Similarly, W–F guilt has been defined as a discrepancy between one’s preferred and actual level of role participation at home versus at work (Hochwarter et al. 2007). Another view is that W–F guilt arises from the perceived failure to adequately fulfill prescribed gender-role norms (Livingston and Judge 2008; Simon 1995). Finally, some authors have speculated that W–F guilt stems from attempts to deal with the double standards that are placed on women as compared to men (Banarjee 2003; Bui 1999).

3 The Measurement of W–F Guilt

Research into W–F guilt has been hampered by a lack of reliable and valid measurement instruments (McElwain and Korabik 2004). As a result, many studies in this area have been qualitative in nature. Some quantitative investigations exist, but mostly these have relied on single-item (e.g., “In the past seven days, how many days have you felt guilty?”) or multi-item measures of general guilt.

Recent meta-analytic results have demonstrated that W–F-specific support constructs are more strongly related to W–F conflict than are the more general constructs of supervisor support and perceived organizational support (Kossek et al. 2011). It is likely that this is also the case for guilt. However, hardly any measures of guilt specific to the W–F context exist and many of these consist of single items (e.g., “I feel guilty that I don’t spend enough time with my family”).

Among the few multi-item measures that are specific to W–F guilt is the Feelings of Guilt about Parenting Scale (Martinez et al. 2011). This 14-item measure was developed and validated in Spain. It assesses situations that could evoke guilt in employed parents (e.g., “Playing with my child for less time than I would like”) on a scale ranging from 1 = not at all guilty to 4 = very guilty. The Spanish version of the scale has excellent internal consistency reliability, and confirmatory factor analysis has indicated that it appears to be unidimensional.

Another measure is an employment-related guilt scale constructed based on the results of interviews and focus groups conducted in Turkey (Aycan and Eskin 2005). The items (e.g., “I feel guilty for not being able to spend as much time as I wish with my children”) are rated on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The internal consistency reliability of the English version is excellent. A similar employment-related guilt scale (Hochwarter et al. 2007) has three items (e.g., “I feel guilty about the time that I am unable to spend with my family due to work”) that are rated on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The measure has good internal consistency reliability.

The W–F guilt scale (WFGS; McElwain 2008; McElwain et al. 2005a) consists of seven items. It differs from the previously discussed measures in that, analogous to the W–F conflict literature, W–F guilt is viewed as being bidirectional. Thus, four of the items assess work interference with family guilt (e.g., “I regret not being around for my family as much as I would like to”) and three assess family interference with work guilt (e.g., “I feel bad because I frequently have to take time away from work to deal with issues happening at home”). The items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. The measure and its subscales have excellent internal consistency reliability and very good test-retest reliability over a 3-month interval. A confirmatory factor analysis established the existence of a two-factor structure with work interference with family guilt (WIFG) and family interference with work guilt (FIWG) as separate dimensions. The WFGS has excellent convergent and discriminant validity. The scale was included in the survey for Project 3535 Footnote 1. Measurement equivalence for culture was established across all ten countries (Korabik and van Rhijn 2014). Measurement equivalence for gender has also been found for the Canadian subsample, indicating that men and women attribute the same meaning to the scale items (McElwain 2008).

McElwain (2008) also created a 24-item faceted version of the W–F guilt scale (WFGS-R). It has six subscales assessing physical, emotional, and psychological WIFG and FIWG . Physical W–F guilt refers to guilt from one’s inability to be physically present to attend to both work and family duties, e.g., “I regret missing family (work) events because of work (family) responsibilities”. Emotional W–F guilt refers to the negative feelings experienced due to W–F conflicts, e.g., “I regret when I take out my frustrations from my work (family) on my family (at work)”. Psychological W–F guilt refers to the psychological spillover from one role to the other, e.g., “I feel guilty for having my family (work) on my mind while at work (spending time with my family)”. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 = never to 7 = always. Thus far, the WFGS-R has only been validated on a sample of women. Despite this, the results look very promising. The internal consistency reliability was excellent. A confirmatory factor analysis verified a structure with two higher order factors (WIFG and FIWG), each with three lower order factors (physical, emotional, and psychological guilt). The measure also has excellent content, convergent, and discriminant validity in the contexts in which it was evaluated (McElwain 2008). There is a high positive correlation between the WIFG subscale from the WFGS-R and the WIFG subscale from the WFGS; however, there is only a moderate positive correlation between the FIWG subscale from the WFGS-R and the FIWG subscale from the WFGS (McElwain 2008).

4 Guilt and the W–F Interface

Several studies have shown that W–F conflict and W–F guilt are interrelated. Aycan and Eskin (2005) found that work interference with family (WIF), but not family interference with work (FIW), was positively correlated with employment-related guilt. Similarly, data from Canada indicate that for both the WFGS and the WFGS-R, significant positive correlations exist between the WIF and WIFG , as well as between the FIW and FIWG subscales . Despite this, scores on W–F guilt do not correlate so highly with those on W–F conflict as to indicate redundancy between these constructs (Korabik and Lero 2004; McElwain 2008; McElwain et al. 2005a, b). As this research is correlational in nature, however, it cannot be determined whether W–F guilt is an antecedent or an outcome of W–F conflict.

Employment-related guilt has been found to be associated with a variety of negative consequences including time inflexibility, depression , and lower satisfaction with life, organizational policies, parenthood , and time spent with children (Aycan and Eskin 2005). Hochwarter et al. (2007) examined whether the ability to manage resources at work could enhance personal control and help to reduce the negative effects of work-induced guilt. They conducted two studies using business school students and public employees as participants, respectively. They found that work-induced guilt had detrimental effects on job and life satisfaction when individuals did not have the ability to manage resources. However, the unfavorable effects of work-related guilt on job and life satisfaction were neutralized when there was an ability to manage resources.

5 Physical Gender and W–F Guilt

Gender is a multidimensional construct consisting of physical and demographic gender,Footnote 2 as well as a range of socialized gender-role characteristics such as gender-role orientation , attitudes, and behaviors (Korabik et al. 2008b). The vast majority of studies into the effects of gender on the W–F interface have focused solely on physical or demographic gender.

In terms of general guilt proneness, gender differences in guilt have been found as early as 33 months. Zahn-Waxler and Kochanska (1988) reported that preschool-aged girls exhibited guilt-related behaviors when they either observed or committed a transgression. Furthermore, girls have been found to be more affected by their wrongdoings than boys (Kochanska et al. 2002). Many other studies have indicated that general guilt levels are higher in women than men (e.g., Kubany and Watson 2003). It is believed that this may stem from the stereotype that women are more interpersonally sensitive than men (Zahn-Waxler et al. 1990), making them more vulnerable to guilt feelings (Zahn-Waxler and Kochanska 1988).

5.1 Qualitative Research

Most of the research on guilt as it specifically applies to the W–F interface has been qualitative in nature, and much of it has employed samples consisting solely of women. For example, Napholz (2000) interviewed eight employed Native American women. They were asked to offer explanations for the feelings of guilt that arose due to their multiple roles. One participant stated that women felt obligated to fix everything and felt guilty when they couldn’t handle all of the demands placed on them. Another respondent said that guilt had driven her to spend more time with her family because she constantly felt like she should be doing more. She admitted to being so preoccupied with guilt that she was unable to properly complete the tasks on which she was working. Some of the women tried to make amends for the guilt by being a “cool” mother or by spending more time with their children.

In another study, Elvin-Nowak (1999) examined W–F guilt in 13 working mothers in Sweden. Participants’ feelings of guilt stemmed from their perceived failure in responsibility toward caring for others. This was due primarily to their lack of control over circumstances which resulted in their inability to balance the demands from their different life spheres. While the mothers felt the most guilt in regard to their children, they also expressed guilt feelings toward their husbands, parents, friends, and coworkers. For example, because these women felt that they should be responsible for mothering their children, they felt guilty when delegating this to someone else (e.g., a babysitter). The women also reported experiencing aggression and anger in reaction to the burden of their guilt feelings. They tried to alleviate the guilt by devising strategies that would allow them to justify putting their own needs first.

Guendouzi (2006) investigated women teachers in the UK, finding that W–F guilt stemmed from trying to achieve an ideal balance between personal and social needs. In addition, she found that guilt resulted from the social pressure placed on mothers to be constantly available and accessible (i.e., the intensive mothering norm). On a related note, Seagram and Daniluk (2002) studied maternal guilt in eight mothers of preadolescent children. They found that the mothers felt a connection or bond with their children and a sense of responsibility for their children’s well-being . This manifested itself both in feeling that they needed to prepare their children for life’s challenges and in fearing their children might come to harm. The participants’ maternal guilt resulted in a sense of inadequacy and emotional depletion (e.g., feelings of anger, frustration, exhaustion, and resentment) .

One component of Project 3535 was to collect qualitative data. The findings revealed that women from a variety of countries mentioned W–F guilt during focus group discussions about W–F balance. These included Australia (Bardoel 2004), Canada (Korabik and Lero 2004; McElwain et al. 2005a), India (Desai and Rajadhyaksha 2004), Indonesia (Mawardi 2004), Israel (Drach-Zahavy and Somech 2004), Taiwan (Huang 2004), and the USA (Velgach et al. 2005). Although there were many similarities, women in different countries tended to emphasize somewhat different themes when speaking about what made them feel guilty. Women in Australia and India were most likely to report experiencing guilt due to their inability to be superwomen (Bardoel 2004; Korabik 2005). Women in the USA mentioned feeling guilty about having to put their jobs before their families and their inability to be in two places at one time (Velgach et al. 2005). By contrast, women in India appeared to experience guilt more when they ignored the academic achievement of their children (Desai and Rajadhyaksha 2004). Women in Indonesia, Taiwan, and the Arab women in Israel spoke about feeling guilty for not fulfilling their traditional gender roles (Korabik 2005). Four of the seven Jewish Israeli women, however, felt that they had moved from guilt to positive spillover as a function of their life stage (Drach-Zahavy and Somech 2004).

More recently, there has been recognition that fathers are not immune from experiencing guilt due to having to deal with the stresses of balancing work and family life (Daly 2001; Martinez et al. 2011). As a result, some qualitative studies have included both men and women as participants. My colleagues and I obtained data from online focus groups with both male and female parents employed by Canadian organizations (Korabik and Lero 2004; Korabik et al. 2007; McElwain et al. 2005a, 2007). When asked if they felt W–F guilt, all participants except one man overwhelmingly indicated that this was a common occurrence. The majority of both men and women said that although they felt guilt both toward balancing their work roles and their family roles, the guilt was strongest in regard to their family responsibilities. Moreover, respondents reported feeling more guilt about their children than their spouses/partners due to a greater sense of responsibility regarding the well-being of their children. Respondents also reported experiencing guilt when their coworkers made them feel that they were not “pulling their weight” at work.

The men and the women were very similar to one another both in the extent to which they admitted experiencing W–F guilt and in the things that made them feel guilty. Despite this, most participants, both men and women alike, believed that there were gender differences in W–F guilt, such that women were more prone to feelings of guilt than men. Some respondents felt that men and women experienced W–F guilt differently either because women were more emotionally sensitive than men or because women were more able to verbalize their feelings than men were. Other participants felt that these gender differences stemmed from societal expectations that men and women should fulfill traditionally prescribed gender roles. Both men and women felt that higher expectations were put on women than on men. Although some men realized that they were currently “getting off easy” compared to women, they did worry that they might have to pay a price later in life for their current neglect of their families.

In another study from Canada, Daly (2001) investigated men and women in both dual-earner and single-parent families. The participants reported feeling guilty about what they were unable to do. The contradiction between their ideal aspirations and the reality of their lives resulted in chronic guilt. More specifically, both women and men felt guilty for working too much, not spending enough time with their children, leaving their children with babysitters, and taking time for themselves. Many had given up on trying to rid themselves of the guilt and had focused on how to live with it.

Simon (1995) compared 40 men and women in dual-earner couples who were employed full-time and had a child under the age of 18 living at home. Eighty-five percent of the women reported feeling guilty because their work took time away from their families and made them feel like they were neglecting their children and spouses. Men, on the other hand, did not report feeling guilty or a feeling of being pulled in different directions. Men’s guilt appeared to stem more from their inability to fulfill their breadwinner role.

In summary, it appears that in many countries around the world women report experiencing W–F guilt. Although there are some cultural differences , their stories have many similar themes. There also seem to be few differences between the extent to which men and women report feeling guilty. Despite this, both men and women hold the stereotype that women are more prone to W–F guilt than are men.

5.2 Quantitative Research

The quantitative research on physical/demographic gender and W–F guilt is still quite sparse. In an early study with a sample of all women, Nevill and Damico (1977) found that those between the ages of 25 and 39 reported significantly higher levels of guilt due to the stress experienced from competing role demands than women at other ages. They suggested that because older women had older children who required less supervision, they were more able to pursue their individual goals without feeling as though they were doing so at the expense of others.

5.2.1 Mean Gender Differences in W–F Guilt

Among the few studies that have examined whether W–F guilt is more prevalent in men or women, the results have been mixed. Aycan and Eskin (2005) found that women reported significantly higher levels of employment-related guilt than did men. However, there was still a significant relationship between W–F conflict and guilt for men. By contrast, Hochwarter et al. (2007) found no correlation between gender and employment-related guilt in either of their samples. Martinez et al. (2011) found that mothers and fathers of preschoolers in Spain were similar in reporting high levels of guilt on the Guilt About Parenting Scale. Both mothers and fathers felt guilty that they could not pay as much attention to their children as they wanted and because they had to delegate some parenting tasks to others. However, mothers’ guilt was more related to their fear that they were not being a “good” mother, whereas fathers’ guilt was more related to their conflict between their desire to be involved with their children and their need to be breadwinners.

Data on the WFGS from Project 3535 indicated no significant overall main effect for gender or gender by country interaction for either WIFG or FIWG . However, in the Canadian subsample men scored significantly higher than women on WIFG (McElwain 2008), whereas in the Israeli subsample women scored significantly higher than men on FIWG.

5.2.2 Gender Differences in How W–F Guilt Relates to Antecedents and Outcomes

My colleagues and I conducted research examining the antecedents and outcomes of W–F guilt (Korabik and McElwain 2011; Korabik et al. 2009). We collected data from two samples of employed parents in Canada. The first consisted of 171 employed women who completed both the WFGS and the WFGS-R along with measures of antecedent (i.e., demands, W–F conflict) and outcome (e.g., satisfaction, turnover intent) variables on one occasion. The second sample consisted of 264 men and 180 women who were employed and who were married/cohabiting parents. They completed the WFGS and measures of the antecedent and outcome variables. Data on the outcome variables were also collected three months later from a subsample of this group (122 men and 138 women).

We carried out a variety of structural equation modeling analyses on the data to try to understand what was driving the effects (i.e., the gender composition of the sample, the version of W–F guilt scale used, or use of a cross sectional versus prospective design). The results can be found in Table 8.1. Column 1 displays the effects for the all-women sample on the WFGS-R using a cross-sectional design, whereas Column 2 displays the effects for the same sample and design, but using the WFGS as the measure. Column 3 displays the effects for the mixed gender sample (N = 444) on the WFGS using a cross-sectional design. Column 4 displays the effects for the mixed gender subsample (N = 260) on the WFGS using a prospective design.

As can be seen, except for the fact that higher FIWG did not significantly predict a lack of family satisfaction or greater psychological distress, most of the relationships were significant in the expected direction. Moreover, most of the relationships were consistent across samples, measures, and designs. The exception was that higher WIFG did not predict lower job satisfaction or higher turnover intentions when a prospective design was used. This pattern of effects indicates that the gender composition of the sample (all women versus mixed gender) did not have an impact on the results. This may have been due to the fact that many extraneous factors that often produce spurious gender effects had been controlled (Korabik et al. 2008b). For example, in the mixed gender sample, the men and women were similar to one another in that they were all employed parents who were married/cohabiting. However, although the results appear similar for men and women, additional analyses on the mixed gender sample data specifically testing whether the men’s and women’s models differ significantly from one another are necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn regarding a lack of gender differences.

5.2.3 Gender in Context

Shields (2013) has argued that we need to move away from studying whether men and women are different from one another and toward studying gender in context or what factors accentuate or diminish gender differences. In this regard, Glavin et al. (2011) examined the impact of work interruptions outside of work hours. In their large sample of employed American adults, they found that women reported higher levels of general guilt than men. Moreover, among women, but not men, the frequency of work interruptions outside of work hours was positively correlated with guilt, and guilt mediated the association between work contact outside of work hours and psychological distress even after W–F conflict was controlled. In a similar study, Offer and Schneider (2011) examined mothers and fathers in dual-earner families in the USA. They found no gender differences on their single-item family time guilt measure. However, for mothers, but not fathers, greater frequency of W–F multitasking at work and in public places was associated with more family time guilt. Dealing with work interruptions outside of work hours and engaging in W–F multitasking are circumstances that are characterized by low control coupled with high demands/overload. In the literature on W–F guilt, issues related to demands, overload , and control have often been mentioned as being important (Aycan and Eskin 2005; Elvin-Nowak 1999; Hochwarter et al. 2007; Napholz 2000). Thus, the relationship between gender and W–F guilt may be impacted by contextual variables such as overload and control.

To address this possibility, my colleagues and I used the WFGS with samples of employees from the USA (Ishaya et al. 2013) and Canada (Ewles et al. 2013). We examined the effects of gender, work and family overload, and job and family control on WIFG and FIWG , respectively. For both men and women in Canada, higher work overload predicted higher WIFG. However, in the USA, WIF moderated this relationship. A lack of job control was predictive of higher WIFG for both genders in the USA, but was not a significant predictor in the Canadian sample. In both the USA and Canada, greater family overload was related to higher WIFG for both genders. A lack of family control predicted higher WIFG for both genders in the USA, but this held true only for women in Canada. Finally, in both the USA and Canada, higher family overload was associated with greater FIWG for men, but not for women. It is difficult to reconcile the disparate findings about how gender interacts with overload and control to impact W–F guilt. This is because the various studies carried out thus far differ as to their samples, their designs, and the measures of W–F guilt used.

Social support has been found to help alleviate the negative effects of W–F conflict (Ayman and Antani 2008). Aycan and Eskin (2005) found that for women, but not men, supervisory support and emotional spousal support were associated with lower work-induced guilt. We (Ewles et al. 2014) used the WFGS to examine gender differences in how received social support from work and nonwork sources was related to W–F guilt. Support from work-related sources (supervisors and coworkers) for work-related issues was not significantly related to WIFG , but it was associated with significantly lower FIWG for those of both genders. In terms of support for family-related issues, when supervisors provided support for household tasks, men were more likely than women to report higher WIFG. By contrast, the more the supervisors and coworkers provided encouragement and appreciation regarding the family, the lower the FIWG for both men and women. Greater support for work-related duties by spouses/partners, neighbors, relatives, and friends was associated with greater WIFG for both genders. Conversely, for both men and women there was no significant association between the support received from nonwork sources for work-related issues and FIWG. However, when their parents/in-laws provided support for both work and family issues, women were significantly more likely than men to report higher WIFG. Furthermore, when they received appreciation from their spouses/partners regarding their work or family life or from their children regarding their family life, men reported significantly lower WIFG than women. Finally, for both genders, the more often children, neighbors, relatives, and friends listened to and discussed family-related problems, the lower the FIWG . These results indicated that the effects of gender and social support on W–F guilt are complex and depend upon the source, domain, type of support, and the direction of W–F guilt examined.

6 Gender-Role Attitudes/Ideology and W–F Guilt

Gender-role ideology (GRI) refers to the attitudes or beliefs an individual holds about the proper roles of men and women in society. It is generally conceptualized as a unidimensional construct with traditional attitudes at one pole and egalitarian attitudes at the other. Chappell et al. (2005) studied a small sample of dual-earner parents from Canada using the WFGS. They found that men with egalitarian GRI reported experiencing more FIWG than traditional men. Egalitarian men also reported higher levels of FIWG than egalitarian women. No significant results were found for WIFG . The Project 3535 data, however, showed a different pattern of results. Those with egalitarian attitudes had lower WIFG than those with traditional attitudes in every country except China (where there was no significant difference) and Turkey (where traditionals had lower WIFG than egalitarians). For FIWG, those with egalitarian attitudes were also lower than those with traditional attitudes in every country except Spain (where there was no significant difference) and Turkey (where traditionals had lower FIWG than egalitarians). Over all countries, both men and women with egalitarian attitudes reported lower FIWG than those with traditional attitudes . However, for WIFG there was an interaction between gender and GRI such that egalitarian men scored higher than traditional men, whereas traditional women scored higher than egalitarian women.

The Project 3535 data from India, Indonesia, and Taiwan were examined by Rajadhyaksha et al. (2011). They established that their GRI scale had measurement equivalence for culture , and found no differences in the gender-role attitudes of men and women in each country. In structural equation models , GRI was treated as an antecedent variable that impacted WIFG via work overload and WIF and impacted FIWG via family overload and FIW. GRI predicted W–F guilt in the same way in each country such that more traditional GRI was associated with higher WIFG and FIWG.

Livingston and Judge (2008) looked at how traditional/egalitarian attitudes and W–F conflict were related to general guilt. They found that there was a stronger positive relationship between WIF and guilt for those with more egalitarian gender role attitudes than for those with more traditional attitudes. By contrast, there was a stronger positive relationship between FIW and guilt for those with traditional gender-role attitudes than for those with egalitarian gender-role attitudes. However, there was an interaction between gender and FIW. Traditional men reported the highest levels of guilt and this was exacerbated when FIW was high. By contrast, egalitarian men reported the lowest levels of guilt, and this was particularly so when FIW was high. Traditional and egalitarian women reported moderate levels of guilt.

7 Gender-Role Orientation and W–F Guilt

Gender-role orientation refers to those personality characteristics in the instrumental/ agentic and expressive/communal domains that are acquired through gender-role socialization . McElwain et al. (2004) used the WFGS to examine W–F conflict and W–F guilt with respect to gender-role orientation as assessed by the Extended Personal Attributes Questionnaire. Participants were dual-earner employed parents from Canada. W–F guilt was significantly related only to the instrumentality aspect of gender-role orientation such that those lower in instrumentality (feminine and undifferentiated individuals) had higher levels of FIWG than those higher in instrumentality (masculine and androgynous individuals). There were no significant differences between those in the different gender role groups in their levels of WIFG.

8 Summary and Critique of the Literature

Research on gender and W–F guilt is still in its infancy. Despite a tremendous interest in the issue, empirical research on the subject is very limited. Mirroring the literature on gender and emotions (Shields 2013), the overall picture is currently one of few gender differences and many inconsistent results. Where differences have been found, results are often congruent with the stereotype of women as being more guilt-prone than men. What’s more, such findings have been more frequent when global, nonspecific measures of self-reported guilt have been used and when women have been sampled from the general population regardless of their employment, marital, or parental status. This may be because under such circumstances societal gender stereotypes are more likely to influence self-construals to produce stereotyped gender differences on self-reports about emotions (Shields 2013).

Research in this area may also be characterized by a lack of meaningful and consistent results because it suffers from a number of other methodological limitations. First, many studies on W–F guilt have employed qualitative methodologies, and most of these have used samples comprised solely of women. Not only can conclusions about gender differences not be drawn from such data, but an implicit assumption behind such research is that W–F guilt is a woman’s problem that does not pertain to men.

Second, when comparative research has been carried out, it has consisted almost exclusively of atheoretical studies of physical/demographic gender. This is particularly problematic when it pertains to gender and emotions. If a theoretical reason for why gender differences exist is not provided, the categories of man/woman can become reified and used as the explanation (Shields 2013). Moreover, this can produce conceptual confusion and result in physical gender being employed as a proxy for some other variable, something that introduces confounds into the research (Korabik et al. 2008b). For example, physical gender is frequently used as a proxy for gender role variables like gender-role orientation . In this case, findings regarding W–F guilt can be mistakenly attributed to whether someone is a man or woman instead of to the degree of instrumentality and expressivity in their personality. Moreover, in our society, physical gender is a status marker. Because of this, when research fails to control for status-related variables (e.g., job level), differences in W–F guilt may be mistakenly attributed to whether someone is a man or a woman rather than to gender-related status differences (Korabik et al. 2008b).

A third problem is that W–F guilt has often been assessed with one-item measures of unsupported reliability and validity or with measures of general guilt, which are only moderately correlated with W–F specific measures like the WFGS (McElwain 2008). Fourth, a wide variety of different operationalizations, measures, samples, and designs have been used, making it very difficult to compare the results of different studies to one another.

9 Future Directions

Clearly, much more research on the topic of gender and W–F guilt is necessary. This should include studies that focus not only on physical gender, but also on gender role constructs. Researchers should be careful to articulate their theory about why they expect gender differences to exist and to use gender-related constructs that are appropriate to the underlying processes that they are studying (i.e., intrapsychic, interpersonal, or social structural) (Korabik et al. 2008b). In addition, more attention needs to be paid to making sure that confounding variables are controlled and to examining gender in context (Korabik et al. 2008b; Shields 2013).

Future research should employ multi-item bidirectional measures created specifically to assess W–F guilt. For example, the WFGS has been shown to be psychometrically sound and to evidence measurement equivalence across a number of cultures . It is also essential to establish the measurement equivalence for gender of any W–F guilt measure before going on to draw any conclusions regarding gender differences. If this is not done, any differences found may be due to the different meaning that men and women attribute to the scale items rather than to actual gender differences.

Thus far, most quantitative research on gender and W–F guilt has been correlational in nature, making it impossible to draw strong inferences about causality. Furthermore, W–F guilt has been variously conceptualized as an antecedent to W–F conflict, as an outcome of W–F conflict, and as a mediator of the relationships between WIF and FIW and outcomes. Longitudinal data is necessary to understand the place of W–F guilt in the larger context of the W–F interface.

10 Conclusion

W–F guilt is frequently discussed in the literature on W–F conflict as being an important phenomenon. Gender-related effects in this area appear to be complex and dependent upon participant characteristics (e.g., marital, parental, and employment status), culture , and the direction of W–F guilt assessed (WIFG versus FIWG). In addition, it appears that variables such as the degree of control, overload , and social support in the work and family domains may be important moderators .

When it comes to gender, it is crucial that we do not fall into the traps of viewing W–F guilt as primarily a woman’s concern or of accepting gender-related stereotypes as reality (Shields 2013). In addition, it is important not to overgeneralize results so as to emphasize between-gender differences at the expense of within-gender variability (Shields 2013). For example, we must recognize that not all mothers are the same, nor are all fathers, and that many different types of families exist. Likewise, the potential impact of race and culture cannot be underestimated.

Dealing with the combined pressures of work and family is a major issue for employees in today’s global workforce (Korabik et al. 2008a). The ensuing stress can result in W–F guilt, a negative emotional state that is associated with a variety of consequences detrimental to individual workers as well as to their organizations, including decreased job and life satisfaction and increased psychological distress, depression , and turnover intentions . Understanding what makes people feel guilty, why they feel guilty, under what circumstances they feel guilty, and the gender dynamics underlying these processes will assist us in designing interventions that will improve the well-being of individual workers and the bottom line of organizations.

Notes

- 1.

Project 3535 is a collaborative investigation of the W–F interface among employed married/cohabiting parents in ten countries (i.e., Australia, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Israel, Spain, Taiwan, Turkey, and the USA). The contributions of the members of the Project 3535 research team to this chapter are gratefully acknowledged. The team consists of: Dr. Zeynep Aycan, Dr. Roya Ayman, Dr. Anne Bardoel, Dr. Tripti Desai, Dr. Anat Drach-Zahavy, Dr. Leslie B. Hammer, Dr. Ting-Pang Huang, Dr. Karen Korabik, Dr. Donna S. Lero, Dr. Artiwadi Mawardi, Dr. Steven Poelmans, Dr. Ujvala Rajadhyaksha, Dr. Anit Somech, and Dr. Li Zhang.

- 2.

Physical gender (whether someone is, or considers themselves to be, a man or a woman) refers to the psychological ramifications of biological sex (whether someone is biologically male or female). This terminology avoids assumptions of biopsychological equivalence (equating sex and gender with one another) and biological essentialism (the belief that behavior is solely attributable to biological causes). In self-report studies, physical gender is not directly observed, rather it is assessed by proxy as a demographic category. For simplicity’s sake, in this chapter the term gender is used to refer to physical and demographic gender in contrast to the term gender-role which is used to refer to gender-role orientation, attitudes, ideology, etc.

References

Aycan, Z., & Eskin, M. (2005). Relative contribution of childcare, spousal, and organizational support in reducing work–family conflict for males and females: The case of Turkey. Sex Roles, 53, 453–471.

Ayman, R., & Antani, A. (2008). Social support and work–family conflict. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work–family integration: Research, theory, and best practices (pp. 287–304). San Diego: Elseiver.

Banarjee, S. (1–3 Nov 2003). Double standards. Businessline.

Bardoel, A. (April 2004). Work family conflict in Anglo-Saxon and European cultural context: The case of Australia. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Bort, J., Pflock, A., & Renner, D. (2005). Mommy guilt: Learn to worry less, focus on what matters most, and raise happier kids. New York: American Management Association.

Bui, L. S. (1999). Mothers in public relations: How are they balancing career and family? Public Relations Quarterly, 44, 23–26.

Chapman, F. S. (Feb 1987). Executive guilt: Who’s taking care of the children? Fortune, 115 (4), 30–37.

Chappell, D. B., Korabik, K., & McElwain, A. (June 2005). The effects of gender-role attitudes on work–family conflict and work–family guilt. Poster presented at the Canadian Psychological Association, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Conlin, M. (2000). The new debate over working moms: As more moms choose to stay home, office life is again under fire. Business Week, 3699, 102–104.

Daly, K. J. (2001). Deconstructing family time: From ideology to lived experience. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 283–294.

Desai, T. P., & Rajadhyaksha, U. (April 2004). Work family conflict in the Asian cultural context: The case of India. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Drach-Zahavy, A., & Somech, A. (April 2004). Work family conflict in the Middle Eastern cultural context: The case of Israel. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Elvin-Nowak, Y. (1999). The meaning of guilt: A phenomenological description of employed mothers’ experiences of guilt. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 73–83.

Ewles, G., Korabik, K., & Lero, D. S. (June 2013). Work–family guilt: The role of overload and control. Poster presented at the Canadian Psychological Association, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

Ewles, G., Korabik, K., & Lero, D. S. (June 2014). Social support and work–family guilt: The role of gender differences. Poster presented at the Canadian Psychological Association, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Glavin, P., Scheiman, S., & Reid, S. (2011). Boundary spanning work demands and their consequences for work and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 43–57.

Guendouzi, J. (2006). “The guilt thing”: Balancing domestic and professional roles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 901–909.

Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewé, P. L., Meurs, J. A., & Kacmar, C. (2007). The interactive effects of work-induced guilt and ability to manage resources on job and life satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 125–135.

Hoffman, M. L. (1982). Development of prosocial motivation: Empathy and guilt. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), The development of prosocial behaviour. New York: Academic.

Huang, T. P. (Aug 2004). Work–family conflict of employees in business organizations in Taiwan. Paper presented at the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Xi’an, China.

Ishaya, N., Ayman, R., & Korabik, K. (April 2013). Why so much guilt? Investigating how overload hurts, and why control may help. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Houston, Texas, USA.

Kochanska, G., Gross, J., Lin, M., & Nichols, K. (2002). Guilt in young children: Development, determinants, and relations with a broader system of standards. Child Development, 73, 461–482.

Korabik, K. (July 2005). Alleviating work–family conflict for women managers in a global context. Paper presented at the Eastern Academy of Management, Cape Town, South Africa.

Korabik, K., & Lero, D. S. (Aug 2004). A cross-cultural research project on the work–family interface: Preliminary findings. Paper presented at the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Xi’an, China.

Korabik, K., & McElwain, A. (April 2011). The role of work–family guilt in work–family conflict. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Korabik, K., & van Rhijn, T. R. (May 2014). Examining the cross-cultural measurement equivalence of work–family interface measures. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

Korabik, K., McElwain, A., Warner, M., & Lero, D. S. (July 2007). The impact of coworker support and resentment on work–family conflict. Paper presented at IESE Conference on Work and Family, Barcelona, Spain.

Korabik, K., Lero, D. S., & Whitehead, D. L. (Eds). (2008a). Handbook of work–family integration: Research, theory, and best practices. San Diego: Elseiver.

Korabik, K., McElwain, A., & Chappell, D. B. (2008b). Integrating gender-related issues into research on work and family. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds), Handbook of work–family integration: Research, theories, and best practices (pp. 215–232). San Diego: Elsevier.

Korabik, K., McElwain, A., & Lero, D. S. (Nov 2009). Does work–family guilt mediate relationships between work–family conflict and outcome variables? Paper presented at the Work, Stress and Health Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Kossek, E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64, 289–313.

Kubany, E. S. (1994). A cognitive model of guilt typology in combat-related PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7, 3–19.

Kubany, E. S., Haynes, S. N., Abueg, F. R., Manke, F. P., Brennan, J. M., & Starhura, C. (1996). Development and validation of the Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI). Psychological Assessment, 5, 428–444.

Kubany, E. S., & Watson, S. B. (2003). Guilt: Elaboration of a multidimensional model. The Psychological Record, 53, 51–90.

Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work–family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 207–216.

Martinez, P., Carrasco, M. J., Aza, G., Blanco, A., & Espinar, I. (2011). Family gender role and guilt in Spanish dual earner families. Sex Roles, 65, 813–826.

Mawardi, A. (April 2004). Work–family conflict in an Asian cultural context: The case of Indonesia. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

McElwain, A. (2008). An examination of the reliability and validity of the Work–family Guilt Scale. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

McElwain, A., & Korabik, K. (2004). Work–family guilt. In M. Pitt-Catsouphes & E. Kossek (Eds.). Work and Family Encyclopedia Online. Chestnut Hill, MA: Sloan Work and Family Research Network. Retrieved February 16, 2009, from http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/encyclopedia_entry.php?id=871&area=All.

McElwain, A., Korabik, K., & Chappell, D. B. (Aug 2004). Beyond gender: Re-examining work–family conflict and work–family guilt in the context of gender-role orientation. Paper presented at the International Society for the Study of Work and Organizational Values, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

McElwain, A., Korabik, K., & Chappell, D. B. (June 2005a). The work–family guilt scale. Poster presented at the Canadian Psychological Association, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

McElwain, A., Korabik, K., & Chappell, D. B. (June 2005b). The impact of work–family conflict on work–family guilt. Poster presented at the Canadian Psychological Association, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

McElwain, A., Korabik, K., & Lero, D. S. (June 2007). Coping mechanisms in work–family conflict. Paper presented at the Canadian Psychological Association. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Napholz, L. (2000). Balancing multiple roles among a group of urban midlife American Indian working women. Health Care for Women International, 27, 255–266.

Nevill, D., & Damico, S. (1977). Developmental components of role conflict in women. The Journal of Psychology, 95, 195–198.

Offer, S., & Schneider, B. (2011). Revisitng the gender gap in time use patterns: Multitasking and well-being among mothers and fathers in dual-earner families. American Sociological Review, 76, 809–833.

Pollock, E. J. (10–13 March 1997). Work and family (a special report): Regaining a balance—This is home; This is work. Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition).

Rajadhyaksha, U., Huang, T. P., Mawardi, A., & Desai, T. P. (July 2011). Gender-role ideology, work–family overload, conflict and guilt: Examining a path analysis model in three Asian countries. Paper presented at the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey.

Seagram, S., & Daniluk, J. C. (2002). It goes with the territory: The meaning and experience of maternal guilt for mothers of preadolescent children. Women and Therapy, 25, 61–88.

Shields, S. A. (2013). Gender and emotions: What we think we know, what we need to know, and why it matters. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37, 423–435.

Simon, R. W. (1995). Gender, multiple roles, role meaning, and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 36, 182–194.

Velgach, S., Ishaya, N., & Ayman, R. (April 2005). A multi-method approach to investigate work–family conflict. Paper presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Zahn-Waxler, C., & Kochanska, G. (1988). The origins of guilt. In R. A. Thompson (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 36. Sociometric Development (pp. 183–258). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Kochanska, G., Krupnick, J., & McKnew, D. (1990). Patterns of guilt in children of depressed and well mothers. Developmental Psychology, 26, 51–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Korabik, K. (2015). The Intersection of Gender and Work–Family Guilt. In: Mills, M. (eds) Gender and the Work-Family Experience. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08891-4_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08891-4_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08890-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08891-4

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)