Abstract

A rapid assessment of potato production and productivity in Kigezi and Elgon highlands was conducted with the aim of understanding the extent of input use and the relationship between input use and productivity. Data from the Uganda Census of Agriculture 2008/09 and a Rapid Rural Appraisal survey were used in the analysis. The results revealed that Kigezi highlands led in potato production and productivity in Uganda. This could be attributed to the higher application/unit area of all inputs. Furthermore, the results indicated that, although the use of productivity-enhancing inputs, such as good quality seeds, fertilizer and fungicides, is fundamental to increasing potato yield in Uganda, the high prices of these inputs vis-à-vis the low prices for ware potato may render their application economically unviable. The results thus suggest the need to ascertain the economically optimal level of input use to minimize low or even negative marginal returns.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum) is an important crop in Uganda particularly in the highland areas where it is a staple food and a main source of income. The highlands in Uganda comprising Kigezi, Elgon and Rwenzori have more or less similar characteristics. That is, they lie at an altitude of 1,300–3,950 masl; the temperature ranges from 12 to 25° C; annual rainfall is bimodal and usually above 1,400 mm (NAADS 2004). Furthermore, these regions are generally densely populated, have young volcanic soils and land is fragmented into small plots (NAADS 2004). Kigezi highlands, found in south-western Uganda, comprises Kabale, Kisoro, Kanungu and Rukungiri districts; Elgon highlands in eastern Uganda include the districts of Mbale, Sironko, Manafwa, Bududa, Kapchorwa and Bukwo, according to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics report, June 2008 (UBoS 2008).

Because of the economic and food security importance of potato, the Government of Uganda and development agencies have implemented several interventions aimed at increasing the output and productivity of this crop. The national research system, for example, has released over 15 potato varieties since 1970 (Kaguongo et al. 2008). The NAADS programme, which is a government extension system, distributes seed potato and other recommended inputs, including fertilizers and fungicides, to farmers in districts where the crop is a priority enterprise under the NAADS programme. In addition, non-governmental agencies, such as the International Potato Center (CIP), African Highlands Initiative (AHI) and AFRICARE, have for over two decades supported potato production and post-harvest initiatives in Kigezi and Elgon highlands.

Notwithstanding the interventions, the potato yield in Uganda is still low, averaging 5 t/ha but with wide disparity in yields by region: Central 2.8 t/ha; Eastern 3.6 t/ha; Northern 2.2 t/ha and Western 5.2 t/ha compared with a potential yield of over 30 t/ha. The 5-year national development plan attributes low agricultural productivity to low and/or inadequate use of recommended production inputs (GoU 2010). For potato production, the key inputs recommended by the providers of extension services and/or provided by the NAADS programme to farmers include ‘quality’ seed potato, fungicides and fertilizer. There are no approved quality standards for seed potato production in Uganda or farms approved to produce such seeds. As a result, farmers rely on personal judgment or advice from agricultural extension staff when selecting the planting materials.

Although various initiatives, as highlighted above, have been undertaken in the country to promote the use of recommended inputs in potato production, little is known about the extent of use of these inputs. Furthermore, not much is known with regard to yield and profit arising from their use. Kelly (2006) argues that the use of improved technologies, particularly by smallholder farmers, depends on economic viability besides physical productivity. The objective of the study, therefore, was to examine the extent of use of recommended inputs including seed potato, fungicides and fertilizer in potato production; especially in the highlands of Uganda. Secondly, the study sought to provide insights into the relationship between the use of recommended inputs and productivity as measured by yield and profit.

Data and Methods

The study used two sets of data: secondary data from the Uganda Census of Agriculture (UCA) survey 2008/09 and from a primary survey. The data from the UCA survey, which covered the entire country, were collected by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBoS), the statutory national agency for data collection. The UCA survey was a sample census collected from 31,340 households. Of these, 2,297 households (7.3 %) were potato producers. In particular, 790 (34.4 %) of the sample households were from Kigezi and 82 (3.6 %) from Elgon. In terms of data collection by cropping season, 1,206 potato producing households were sampled in Season 2 (July–December) 2008 and 1,091 in Season 1 (January–June) 2009. The UBoS included weights (inflation factors) in the UCA survey to make the sample nationally representative.

The UCA survey had six modules, including those for Agricultural Household and Holding, Crop Area and Crop Production, (UBoS 2008). In the survey, data were quantitative on the area cultivated and qualitative on the use of inputs. The UCA data, however, did not include a section on the quantity and price of inputs as well as the price of outputs, which would be useful for economic analysis.

In view of the fact that data on the quantity and value of inputs used in potato production as well as outputs were missing in UCA 2008/09, a rapid rural appraisal (RRA) was conducted in Kigezi and Elgon highlands to collect these data quickly and cost-effectively from key informants including farmers, traders, processors, transporters, brokers, local government officials, researchers and extension agents. For the purpose of this paper, only data collected from farmers were utilized. The RRA research method integrates elements of formal surveys and unstructured methods of research, such as in-depth interviews or focus group studies (Crawford 1997).

A semi-structured questionnaire was designed and administered to 60 farmers: 30 from Kigezi and 30 from Elgon as one group of key informants in the potato value-chain. In Kigezi, data were collected from 15 farmers in Kabale district and 15 in Kisoro district. Similarly in Elgon, data were collected from 15 farmers in Mbale district and 15 in Kapchorwa district. At the district level, the selection of potato producers was purposive and guided jointly by the District Coordinator of NAADS and the Chairperson of the District Farmers’ Fora who by virtue of their work are in close contact with farmers. Target respondents were from at least two sub-counties and included both subsistence farmers and market-oriented producers as classified in the NAADS programme.

As this was a semi-structured questionnaire, both quantitative and qualitative responses were solicited. Quantitative data among others included those on the quantity and price of inputs and outputs and marketing costs. Qualitative responses were solicited to provide further details with regard to quantitative data. Original survey data were standardized in metric units. For example, the area cultivated, which was reported in acres, was standardized to hectares; output, which was reported in bags, was converted into kilograms: one bag was assumed to weigh an average of 100 kg.

Descriptive and analytical methods, supported with qualitative narratives, were both used in the study. For example, the two-group mean-comparison test (Park 2009) was used to compare the extent of input use and the yield and profit outcome of potato producers in the study areas. Two-way fractional polynomial graphs were fitted to provide causal insights of the predicted relationship between the extent of fertilizer and/or fungicide use and the yield and/or profit. Fractional polynomials are alternative approaches to the traditional approaches for the analysis of continuous variables (Royston et al. 1999). Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (Eq. 3.1) of yield/profit (y) on quantity of seeds (x 1 ), fertilizer (x 2 ), fungicides (x 3 ) and cost of labour and other inputs (x 4 ) was estimated to assess the statistical significance of the relationships. Where α and β in Eq. 3.1 are unknowns to be estimated and ε is the random term.

Results and Discussion

Table 3.1 shows the total area cultivated, output and yield of potato in Kigezi and Elgon highlands and the rest of the country. Results revealed that Kigezi produced almost half (47 %) of the national potato output on 40 % of total crop area in Uganda. Results furthermore indicated that potato yield in Kigezi was almost double that in Elgon.

Despite the fact that Elgon highlands lagged behind in production, on average, a higher proportion (59 %) of potato producers in this area use fertilizer compared with only 18 % in Kigezi (Fig. 3.1). Based on 2005 data, Kaguongo et al. (2008) reported that 40 % of potato producers in Elgon used fertilizer compared with 7 % in Kigezi. Interviews with farmers in Elgon revealed that this relatively high proportion was likely to be due to the long tradition of using fertilizer as a result of continuous information from the district authorities on land management. Communities living in Elgon face a severe land shortage, with fragmentation and degradation (Ingram and Reed 1998), which limits the expansion of the cultivated area. The availability of relatively cheap fertilizers imported/smuggled from Kenya, particularly in Kapchorwa district, was also cited by respondents as another possible factor. In contrast, the relatively low proportion of farmers using fertilizer in Kigezi was likely to be due to the scarcity and relatively high price of fertilizer as a result of the poor transport services in the area. Kaguongo et al. (2008) observe that the low use of fertilizers in Kigezi is rooted in the perception that land in the region was inherently fertile and there was no need to use external nutrient inputs.

In both Kigezi and Elgon, the RRA survey revealed that diammonium phosphate (DAP) and nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (NPK) compound were the prevalent types of fertilizers used in potato production and applied mainly at the planting stage. A higher proportion (35 %) of farmers in Kigezi used fungicides than their counterparts in Elgon (29 %). Respondents reported the use of either Dithane M-45 or Ridomil Gold 68 WP. Rather more farmers use fungicides, particularly in Kigezi, and this may be due to the fact that, unlike fertilizer, fungicides were less bulky, available even in rural input shops, retailed in smaller quantities, such as 0.5 kg, and had a multipurpose use, including the control of diseases in other crops, such as tomato. Moreover, fungicides were highly recommended by extension workers for the control of a wide range of crop disease vectors.

The use of quality seed potato for ware production, in both Kigezi and Elgon highlands was generally low (Fig. 3.1). Most farmers reported using their own seeds retained from the previous harvest or those bought from a neighbour. The widespread use of local seeds, which are mostly likely to be diseased with bacterial wilt, may be another reason for the fairly high proportion of farmers using fungicides across the two regions.

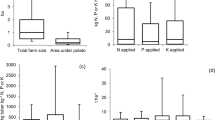

The average level of input use and the corresponding yield and profit in potato production in the two study areas are presented in Table 3.2. Results indicate that mean area cultivated was 0.31 ha, seed use was 1.6 t/ha, fertilizer use was 173 kg/ha and fungicide use was 7.2 kg/ha. Resultant yields averaged 12.2 t/ha while profit averaged US$ 1152.91/ha. Potato producers in Kigezi used more seeds, fertilizer and fungicides/ha than their counterparts in Elgon. Corresponding yield and profit/ha were also significantly higher in Kigezi than in Elgon. All results except the area cultivated were statistically significant at less than 5 % level.

The use of relatively higher quantities/unit area of fertilizer and fungicides in Kigezi compared with Elgon may be due to the different recommendations provided by advisors in the extension services in the two regions, perhaps from a lack of knowledge on the economically optimal rate of input application. Kafeero and Namirembe (2003) observed that community extension agents as well as NAADS service providers do not have a uniform approach to extension services delivery. Also, most extension workers, let alone farmers in Uganda, lack basic and up-to-date knowledge about the state of soil nutrient balances so as to be able to provide appropriate fertilizer recommendations. Consequently, farmers who use fertilizer in crop production in Uganda more often guess than know the economically and/or technically optimal amount of input to apply.

Figure 3.2a shows the relationship between fertilizer use and yield; Fig. 3.2b shows the relationship between fertilizer use and profit. Figure 3.2c, d show the relationship between fungicide use and yield and profit keeping all other factors constant. In Fig. 3.2a–d, the slopes of the graphs of predicted yield and profit are somewhat upward, implying that a unit increase in the quantity of fertilizer or fungicide applied on potato had a positive, though not outstanding, effect on yield and profit.

Table 3.3 presents results of the OLS regression of Eq. 3.1: regression of yield and profit on physical factor inputs. Results indicate that a unit increase in the mean quantity of seeds and/or fungicides used had a positive effect on yield and profit but a unit increase in the mean quantity of fertilizer used had a negative effect. The coefficients of seeds and fertilizer in the profit regression were, however, the only variables that were statistically significant at 5 % and 10 % levels respectively. These results suggest that the mean quantity/ha of seed potato sown/ha by Ugandan potato producers may be below the optimum so that a unit increase in the quantity sown would boost productivity. According to International Year of the Potato (2008), about 2 t/ha of seed potato are sown compared to an average of 1.6 t/ha (Table 3.2) that are planted by farmers in Kigezi and Elgon, Uganda.

As for fertilizer application, results suggest a 1 % reduction in yield and a 3 % reduction in profit for a unit increase (1 kg) in the mean quantity of fertilizer applied. Though the predicted relationship between fertilizer application and yield was not statistically significant, it was rather surprising that it turned out to be negative– implying over-fertilization. In contrast, the fertilizer/profit relationship is not surprising, given the yield response and the relatively high retail price of fertilizer (about US$ 0.8/kg) which is about four times the farm-gate price (US$ 0.2/kg) of ware potato. The other factor that was found to have a significant effect on both yield and profit was the cost of hired labour and other inputs (such as transport and packaging materials).

Conclusions

Kigezi highlands lead in potato production and productivity partly due to a higher application/unit of the cultivated area of all inputs including seeds, fertilizer and fungicides. A higher proportion of farmers in Elgon highlands used fertilizer and fungicides but the rates of application/unit area were lower. Furthermore, results indicate that, while the use of productivity-enhancing inputs, such as good quality seeds, fertilizer and fungicides, is fundamental to increasing potato yield in Uganda, the high prices of these inputs vis-à-vis low prices for ware potato may render their application economically unviable. The results thus suggest a need to assist farmers to ascertain the economically optimal level of input use so as to minimize low or even negative marginal returns that may arise from an uninformed use of the inputs.

References

Bank of Uganda (2011) Monetary policy report, Kampala, Uganda, October 2011

Crawford IM (1997) Marketing research and information systems: marketing and agribusiness texts, vol 4. FAO, Rome

GoU (Government of Uganda) (2010) National development plan [2010/11–2014/15]. Kampala, Uganda

Ingram A, Reed M (1998) Land use and population pressure within and adjacent to Mount Elgon National Park: Implications and potential management strategies. Project Elgon, Leeds University. http://www.see.leeds.ac.uk/misc/elgon/land_use.html. Accessed 20 Oct 2011

International Year of the Potato (2008) http://www.potato2008.org/en/potato/cultivation.html. Accessed 10 Nov 2011

Kafeero F, Namirembe S (2003) Community extension worker approach: a study of lessons and experiences in Uganda for the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS). NAADS Secretariat, Uganda

Kaguongo W, Gildemacher P, Demo P, Wagoire W, Kinyae P, Andrade J, Forbes G, Fugile K, Thiele G (2008) Farmer practices and adoption of improved potato varieties in Kenya and Uganda. International Potato Center (CIP), Lima, Peru. Social sciences working paper 2008-5

Kelly VA (2006) Factors affecting the demand for fertilizer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agriculture and Rural Development discussion paper 23. The World Bank, Washington DC, USA

NAADS (National Agricultural Advisory Services) (2004) Towards zoning agricultural production in Uganda: the NAADS approach. Kampala, Uganda

Park HM (2009) Comparing group means: t-tests and one-way ANOVA using STATA, SAS, R, and SPSS. Working paper. The University Information Technology Services (UITS), Center for Statistical and Mathematical Computing, Indiana University http://www.indiana.edu/~statmath/stat/all/ttest. Accessed 18 Oct 2012

Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W (1999) The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 28(5):964–974

UBoS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics) (2008) Uganda Census of Agriculture: enumerators’ instruction manual. Kampala, Uganda

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Okoboi, G., Kashaija, I., Kakuhenzire, R., Lemaga, B., Tibanyendera, D. (2014). Rapid Assessment of Potato Productivity in Kigezi and Elgon Highlands in Uganda. In: Vanlauwe, B., van Asten, P., Blomme, G. (eds) Challenges and Opportunities for Agricultural Intensification of the Humid Highland Systems of Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07662-1_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07662-1_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-07661-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-07662-1

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)