Abstract

The chapter will focus on the use of Twitter during the 2012 local elections in Belgium. Via a multi-method approach we aim to understand how the Twitter debate links up to mainstream media outlets and how political actors, media actors and citizens interact in this decentralized and interactive Twitter sphere. In doing so, we elaborate on the role of Twitter (as one of the most popular social media platforms) in the agenda setting and building processes between politicians, media and public opinion. Further, we discuss the role of social media, and Twitter in particular, in the rejuvenation of democracy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Agenda Setting in a Mediated Democracy

Our research will focus on the election debate, as conducted on Twitter. Based on the platform’s technical features, myths and prophecies have been articulated about its transformation power on democracy. Both positive and critical accounts are techno-centric as they fail to take into account the context in which these technologies are embedded (Curran et al. 2012). In this respect, the understanding of the mediated political debate via Twitter will focus on the position of and relation between media or journalists, political actors and citizen-audiences.

Related to the ‘blurrification’ of what is public and private on social media, monitoring and scrutinizing the political realm becomes more easy (Papacharissi 2009). In reflecting upon political activity in contemporary society, Rosanvallon (2008) refers to ‘surveillance’ or oversight, reflecting the vigilant citizen and the organization of people as watchdogs. Mass media have traditionally functioned as intermediary system between society and political institutions, but social media enable both citizens and politicians to circumvent the media, and directly influence each other within this networked new media environment (Bruns 2008; Benkler 2006). In addition to the potential to impact agenda setting processes, Twitter carries the promise of more direct forms of democracy (Bruns 2008).

Agenda setting theory, often applied in election campaign research, provides a useful framework to investigate the shifting and dynamic power relationships between these three actors—media, political elites and citizens—each with their own issue agenda (Dearing and Rogers 1996). We recognize that the socio-technological context the agenda setting theory traditionally assumes no longer holds in contemporary society (Chaffee and Metzger 2001; Bennett and Iyengar 2008). The rise and implementation of social media for political purposes potentially challenges the interplay between these agendas and the position of traditional power elites. The shifting dynamics between mainstream media and social media are highly relevant for the functioning of the public sphere and democracy in general.

Political actors can circumvent traditional media and directly address citizen-users, which is convenient during election times when mainstream media focus on party leaders and larger parties (Hermans and Vergeer 2012). At the same time, these mainstream media are still key arenas for political communication (Curran et al. 2012). Their presence in this networked media environment might provide additional possibilities for politicians to access and influence the mass media agenda or endorse and enhance the visibility of particular existing mass media outlets (cf. secondary gatekeeping, Singer 2014). This post-broadcasting era (Prior 2006) fragments and expands the news environment, in which not only citizens, but also politicians can embrace the creativity, interactivity and autonomy that is associated with this decentralized media environment. In reflecting upon the concept of ‘networked politics’ (Curran et al. 2012: 164), notions of interactivity, participation and autonomy need to be empirically understood.

The focus and set-up of the study is to grasp the broader (i.e. socio-technological) spectrum of Twitter use during this highly intense period of public attention upon the elections, guided by the prominent question to what extent and how Twitter can impact agenda setting processes. We focus on the local and regional elections in Belgium, that nonetheless their distinct local orientation received a lot of attention in national media outlets (Epping et al. 2013). During election times, the importance and influence of media increases, for national as well as local campaigning (Van Aelst 2008). Concerning the use of social media, online means of narrow casting to inform and mobilize—specific groups of—citizens (or vice versa) relate to the local nature and social embeddedness of the elections. Next, in the methodology section, we will elaborate on the collection of Twitter data, the possibilities of the Twitter platform for intermedia connections and user interactions and the analysis of the data.

2 Methodology

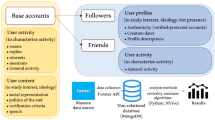

2.1 Context and Data Collection

The case study here concerns the local elections in Belgium, held on the 14th of October 2012. Through the use of the Twitter streaming API, we collected a corpus of 43,447 Twitter messages containing the official hashtag on the local elections (i.e. #vk2012) between the 1st of September and the 21st of October. These messages correspond to 11,658 users participating publicly (i.e. through the use of the hashtag) in the debate. Notwithstanding the substantial number, we make no attempt to generalize this specific userbase to the wider population or the electorate as such. Aside users that represent politicians and/or political parties and media institutes or journalists, it is likely we are dealing with ‘political junkies’ (Coleman 2003) or in similar vein ‘news junkies’ (Prior 2006). These people are highly engaged with news, current affairs and politics in particular.

The country under investigation in this study is Belgium. Based on the media models that Hallin and Mancini (2004) distinguish, Belgium represents a democratic corporatist model. Without extensive elaboration upon all its dimensions, it signifies media autonomy and journalistic professionalization, early development of the mass-circulation press and strong public service broadcasting. The electoral context in Belgium is characterized by a multiparty system, whereby parties compete against one another but must work together with each other to form a local coalition. In this chapter, we focus on Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, as it has a separate media landscape and usage patterns. When we speak of national media, this reflects Flemish media, as there are no national media for Belgium.

Via the open source tool yourTwapperkeeper, Twitter messages containing hashtag #vk2012 are captured and stored in a MySQL database, which allows a flexible approach to subsequent processing. Via the use of Gawk scripts,Footnote 1 key metrics are extracted and stored in Excel databases, which are used for further analysis in SPSS and UCINET (Borgatti et al. 2002). In addition to these computational methods for data processing, manual analysis of the data is executed and discussed below.

2.2 Data Analysis

Our understanding of the Twitter debate in the broader media ecology is twofold and contains (1) an analysis of the Twitter messages with a focus on inter-linkages with other media outlets and (2) an analysis of interactions between politicians, media actors and citizens based on a division of the debate into four periods. The first part will focus on particular characteristics of the messages as such, whereas the second part of the study focuses on the senders and receivers of the messages.

2.2.1 The Twitter Debate in a Multi-Media Constellation

We would like to point to two conventions that reflect intermedia connections on Twitter (with a particular focus on mainstream media), i.e. hashtags and hyperlinks. Hashtags refer to words or phrases in conjunction with the # sign and refer to particular themes or topics (Bruns 2012). These core #themes and #topics can be brought in comparison with traditional media outlets to look for cross-media correspondence in issues. As a content analysis of mass media outlets is not at stake here, we primarily focus on more ‘explicit’ references to traditional media outlets. Through the use of hashtags, e.g. referring to television channels or shows, Twitter users re-distribute and discuss its content (Deller 2011). Flemish TV broadcasters facilitate this via the promotion of dedicated hashtags, related to specific programs. In addition to hashtags, the use of hyperlinks allows the user to refer to other sources on the web, including for example the traditional media’s online news agenda. Hyperlinking practices have been studies in the context of intermedia agenda setting influences between traditional and newer, emerging media such as blogs (Meraz 2011). Twitter, on the other hand, reflects a networked, time-compressed interface consisting of continuous streams of content between users, creating an ambient, always-on news environment (Elmer 2012; Hermida 2010). In this respect, it presents different and/or additional challenges to the agenda setting process.

2.2.2 Interaction Patterns Between Media, Political Actors and Citizens

To allow for one-to-one communication on Twitter, the @ sign is used as a marker of addressivity. Concerning the use of @ signs (i.e. @username), Twitter demarcates ‘replies’ and ‘mentions’, whereby the former puts the @ sign at the beginning of the Tweet, whereas ‘mentions’ do not start the messages with an @ sign. Both conventions predominantly reflect addressivity (Honeycutt and Herring 2009) and were retained for the composition of four different interaction networks. We acknowledge that the hashtag-based approach to collect Twitter messages does not enable us to examine the level of relevant interaction that may take place outside the #hashtag (Bruns 2012).

The division of the Twitter debate into four periods is based on the assumption that each of the different periods represents different dynamics in terms of interaction (or influence) between citizens, media and political actors. The four different time-frames in the debate are the following: the pre-election period (01.09.12–07.10.12), the prior week (08.10.12–13.10.12), election day (14.10.12) and the post-election period (15.10.12–21.10.12). For each period, we discuss the structural characteristics of conversation via Twitter and the position of the different actor types in these conversation networks via the Social Network Analysis Software UCINET (Borgatti et al. 2002). In order to understand communicative patterns between media actors, political actors and citizens, all actors in the network are manually coded alike. We acknowledge Twitter identity is problematic as it is self-defined and therefore does not always fit traditional categorization schemes (Lewis et al. 2013) or remains obscure; e.g. when no user description is provided. The definition of the actors as politicians and media actors and citizens is based on their username and description, as publicly available, at the time the network analysis was conducted (April 2013).

2.3 Findings

In correspondence with the methodology, the discussion of the results is divided into two parts, whereby the first part places the debate within the broader media environment. The second part of the results elaborates on the interaction patterns between media actors, political actors and citizens.

2.3.1 The Twitter Debate in a Multi-Media Constellation

2.3.1.1 A Chronological Overview and Understanding of Twitter Traffic

The timeline as shown in Fig. 6.1 is highly similar to other, international studies on Twitter traffic during the elections (Bruns and Burgess 2011; Larsson and Moe 2012). The graph is characterized by a number of spikes, with the election day representing the largest upsurge in messages. The election day takes up more than 50 % of the total number of tweets from the 1st of September until the 21st of October, or a total of 25,803 messages of the 43,447 messages reflecting the total debate. The peak on election day is excluded from Fig. 6.1, to make visible the more modest increases in Twitter traffic that can be related to offline events staged by traditional media.

The first small spike, the 4th of September, is related to the publication of the list numbers in print and audiovisual media. Before the elections, a lottery takes place to define the numbers of the parties on the elections lists. The second peak, the 12th of September, is related to the election day in the Netherlands, whereby the official hashtag (i.e. #vk2012) is used to discuss the results of the election. October the 5th represents the third peak and is related to the publication of a large-scale study on the upcoming elections in the most prominent cities in Flanders (i.e. Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Leuven, and Hasselt). The election polls were published in print media (including the main news websites) and were discussed on television as well.

The week before the election day, or the fourth increase in traffic indicated on the graph, is characterized by an increase in media attention for the upcoming elections. Especially the public service broadcaster VRT features multiple dedicated programs on the upcoming elections (Epping et al. 2013). During this final week before the elections, the VRT program ‘De Laatste Ronde’ (i.e. ‘the roundup’) reports from five large Flemish municipalities, being Bruges, Leuven, Hasselt, Antwerp, and Ghent. Also, the commercial Flemish broadcaster VTM aired ‘Het Ultieme Debat’ (i.e. ‘the ultimate debate’), containing a final discussion amongst the most prominent candidates. Each of the programs had dedicated hashtags, which allows us to link the increase in Twitter traffic with these televised political debates. Concerning the publication of the list numbers or the election poll that was executed, thematic tags such as #poll or #listnumbers were found.

Considering different traditional media channels, significant (live) television events are often found to relate with spikes in Twitter traffic (Larsson and Moe 2012; Bruns and Burgess 2011). When these shows are watched live, they create a shared viewing experience, allowing real-time and collective comments and discussion which results in upsurges in Twitter traffic.

2.3.1.2 Hyperlinks as Intermedia Connections

In order to understand potential influences between Twitter and other media platforms, one must get a networked understanding of the Twitter environment. On a total of 43,447 Twitter messages, 9,201 short URLs were found, of which the most prominent are analyzed. These relative frequencies are similar to the amount of links that were found for Twitter traffic during the 2010 Australian Federal elections (‘#ausvotes’) (Bruns and Burgess 2011). Interconnections with mainstream media and other content point to the fact that the platform does not stand alone but influences and is influenced by other media channels. Table 6.1 shows the most prominent categories of online resources: social media, traditional media, and official political party websites.

We notice that many URLs refer to other social media, and more specifically Twitter. Taking a closer look at these Twitter links, they almost exclusively refer to photos related to particular user profiles. In addition, platforms such as Twitpic, Instagram, and YouTube were frequently found as well. Generally, we can already say audiovisual material far exceeds more textual sources, whereby we particularly refer to blogs. In this respect, the concept of (intermedia) agenda setting will need to take into account new, creative forms of political communication suggesting affective or social influences in addition to informational ones. As Fenton (2012) points out, social media practices are characterized by affective and social (yet very individual) dimensions of communication.

Concerning references to traditional media, the Twitter platform can be acknowledged as a ‘secondary gatekeeper’ (Singer 2014). Through the incorporation and secondary circulation of the hyperlinks on Twitter, visibility of existing mainstream media outlets increases. As media actors are also present on the platform, they can employ Twitter as an additional channel to increase the visibility of their media outlets. Taking a closer look at the subcategories, we consider both national and regional news media, as the elections concern municipalities and provinces. Concerning the type of content, a distinction is made between broadcasting television and radio on the one hand and print media, including newspapers and magazines, on the other. Television and radio channels provide audiovisual material on their website, allowing users to distribute but also comment TV content without watching it real-time.

External sources to official political party websites seem take a minor part in the Twitter debate, compared to informal, mediated platforms for political communication (i.e. social and mainstream media).

Although the information is not provided in Table 6.1, we discuss the most prominent mainstream media outlets. The website of the Flemish public service broadcaster VRT is most frequently mentioned within the category of national news media. The website provides video footage on news and current affairs programs of the public service broadcaster. As mentioned above, they invested heavily in coverage of the elections and hold an overall strong position in the audiovisual landscape in Flanders. Concerning print media, Flemish newspapers have a freely accessible news website, in addition to their print version. Here, most references refer to a national quality newspaper, called ‘De Standaard’, followed by the popular newspaper ‘Het Nieuwsblad’. Concerning regional media, we found a great number of URLs of ‘Brussel Nieuws’, covering the Belgian capital city of Brussels and ‘TV Limburg’, representing the province of Limburg in Flanders.

2.3.1.3 Hashtags as Intermedia Connections

As mentioned above, the use of hashtags serves to aggregate and categorize Twitter messages around specific topics and are highly visible and searchable elements of the Twitter architecture. In Table 6.2 below, the most common hashtags (i.e. >20) of a total of 3,304 additional hashtags are listed and categorized.

Explicit references to traditional news platforms are very modest compared to hashtags referring to the parties and municipalities. Here again, we found hashtags that relate to audiovisual and print media. Reference to audiovisual material is far more common compared to print, whereas for the hyperlinks this difference is a lot smaller. The use of hashtags whilst (or after) watching particular programs is common in Flanders as broadcasters indicate dedicated hashtags per program. The public service broadcaster VRT (as a channel, as well as its programs) is mentioned more frequently than its commercial opponent VTM. In addition, to a very limited extent, users refer to print newspaper titles, whereby the most popular titles are identical with the results of the hyperlinks. The low amounts of hashtags to mass media outlets does not imply only so much is tweeted. If users indicate only the hashtag of the program, without the one of the elections (i.e. #vk2012), these messages are excluded from the dataset resulting in an underestimation of the actual amount of tweets.

Concerning the other categories provided in the table, it is mostly political parties than are discussed, except for one politician (Bart De Wever), party leader of the N-VA. While we do not aim to focus on the particular parties/politicians here, we would like to put the use of explicit references to traditional media in relation to other hashtags and acknowledge these topical hashtags as potential expressions of more indirect forms of intermedia congruence. In thinking of hashtags as indicators of the content of particular tweets, they indicate the dominant themes and topics of the Twitter platforms. Although this study does not provide a systematic overview of the parties and municipalities discussed in traditional media during election times, we can compare our results with a Flemish study on media attention for political parties, politicians (and the municipalities they represent) on public service TV (Epping et al. 2013). During the election campaign, starting the 1st of September, attention for the political party N-VA and the Bart De Wever is most prominent. In analogy with the results in Table 6.2 above, the public service broadcaster focuses on larger cities, including Antwerp and Ghent. Although the study only represent a part of the traditional mainstream offer, albeit a substantial part, these initial similarities at least allude issue correspondence between traditional media outlets and Twitter.

2.3.2 Interaction Patterns Between Media, Political Actors and Citizens

For the second part of the paper, we move our focus from the content of the messages to the senders and receivers of Twitter messages, i.e. interaction structures and flows. Within the field of Twitter research, network studies seem to be emergent (Bruns 2012). This part of the paper is dedicated to a networked understanding of the Twittersphere during election times. As discussed in the methodology, the second part of the study departs from the division of the Twitter debate into four periods, being: the pre-election period (01.09.12–07.10.12), the prior week (08.10.12–13.10.12), election day (14.10.12) and the post-election period (15.10.12–21.10.12). For each period, we discuss interaction via Twitter and the position of media actors, political actors and citizens.

2.3.2.1 Network Characteristics of Twitter for Conversational Interaction

We start with an overview of the number of participants in each of the debates. For the four consecutive periods, networks are constructed, based on sender-receiver interactions that make use of addressivity markers or @signs, which allows users to direct a tweet to a specific other user. For each of the periods, the ‘main component’ or largest group of connected actors was extracted for further analysis.Footnote 2 Table 6.3 above provides an overview of the total number of actors in the debate and how many of them are media actors, political actors and citizens. Concerning citizen actors, we labeled ‘private individuals’ as citizens when no professional affiliation with media or politics was provided by the user. We acknowledge that this categorization has its shortcomings, as for example prominent academics are included as well, although they were regularly staged by traditional media as experts.

In comparing the different periods, we notice the relative number of political actors, media actors and citizens alters. Although citizen users always represent the largest group, this tendency is most salient for the election day and the period thereafter, which is related to a substantial drop in political actors once the elections took place. It seems that politicians mobilize or are mobilized before the elections (i.e. during campaigning times), which indicates their temporal visibility and presence in the debate. If these interactions are instigated by politicians or political parties, it reflects a rather pragmatic use of the platform. A Danish study on the use of social media in election campaigns elaborates on the purposes of using social media in the campaign mix (Skovsgaard and Van Dalen 2013). The study shows that Danish candidates indicate two important purposes underlying the use of social media, i.e. (1) making their political views visible and (2) directly communicating with voters. Concerning the latter, the authors point to the fact that interaction or dialogue with citizens might be overrated or otherwise said: ideal and actual social media practices do not always correspond. In the following section, we will elaborate on interactive uses of Twitter by political actors, as well as media actors and citizens. For this section, we finish with an understanding of the general network in terms of centrality.

Table 6.4 shows to what extent incoming messages (or ‘in-degree’) or outgoing messages (or ‘out-degree’) are centered around one or very few actors. The numbers signify low levels of centralization, suggesting interactions that are centered around various actors in the debate. The large size of the networks (476–848 actors) contributes to the very low scores. In addition, the results relate to the low number of interactions (or ‘degrees’) that take place between the actors. For all the periods, the average number of interactions between network actors (or ‘nodes’) lies between 1.24 and 1.58 and median scores are 1. This points out a distribution that is strongly skewed to the right, whereby few actors have (very) high amounts of interaction but the most of actors are only related to one other actor in the network. In other words, the strength of the interactions is very low. We do acknowledge that relevant Twitter interactions possibly take place outside the official hashtag on which data collection is based (Bruns 2012) and in this respect an underestimation of the real amount of interactions probably occurred.

2.3.2.2 Inter-group Conversationality and Reciprocity

The final part of the results provides an overview of the interaction patterns among the different actor types, as demarcated above in Table 6.3: media actors, political actors, and citizens.Footnote 3 Aside centralization as a network characteristic, network analysis allows us to look for in-degree (or messages received) and out-degree (or messages sent) centrality per actor. Although the network as such indicates a high level of decentralization, we notice significant differences when we compare media and political actors and citizens.Footnote 4 These differences were found for the average amount of messages actors received, whereas no significant differences were found concerning the number of messages the actors sent. Table 6.5 above provides the differences in in-degree centrality between the three actor types, showing that media and political actors receive a lot more directed messages than citizen. These results endorse the tendencies that similar Twitter studies indicate, based on the Gephi visualization software, i.e. the central positions of users that ‘enjoy privileged positions in their respective professional capacities of journalists, politicians, etc.’ (Larsson and Moe 2012: 740; Bruns and Burgess 2011).

The appropriation of Twitter for conversational interaction reflects two-way exchanges whereby directed messages preferably flow in both directions. Before elaborating on the differences between the actor types, we point out that reciprocity on a network level is very low. In total, 2–4 % of the relations between two actors (or ‘dyads’) are reciprocal.Footnote 5 The discrepancies between the actor types as discussed in Table 6.5 suggest one-way communication going from citizens to established actors, which is further endorses when we look at the reciprocity scores per actor type (see Table 6.6, in italics).

Overall, two-way interaction is mostly established by citizens, as they seek to react to ‘established actors’ that address them personally. However, when citizen actors address these established actors, politicians and/or media actors show much lower levels of reciprocity. In this respect, similar to research during the 2012 Australian elections (Bruns and Burgess 2011), citizen users tweet ‘at or about rather than engaging with’ established elites. Comparing the different periods, we notice that, on the election day, media actors become highly reciprocal towards politicians compared to the other periods. The timing here suggests that rather than politicians engaging with journalists to influence the mass media agenda, the discussion of the election results and the traditional media channels that report them, is at stake here. In addition, responsiveness of citizen users towards politicians drops after the elections, which might insinuate interactions taking place before the elections occur with the upcoming voting practices in mind.

To conclude, network analysis allows us to understand to what extent communication flows among the different actor groups or whether each of the actor types tends towards in-group communication. Obviously, the size of the subpopulations has consequences for the number of internal versus external ties that can be and are formed. For each of the networks, ‘expected E-I values’ are calculated given the structure of the networks, which are then compared to the observed E-I values.Footnote 6 The higher the values in Table 6.7 above, the more obvious the tendency towards out-group communication.

On the election day (period 3) and the week after the elections (period 4) there is a high tendency towards out-group communication. From the perspective of social media use during election campaigns (i.e. to make visible one’s opinions and communicate directly), the periods before the elections should have yielded significant results. Direct communication with voters or with journalists to influence the public and media agenda would be the rationale then (Skovsgaard and Van Dalen 2013). The high ‘out-group’ values for politicians are in conjunction with the higher number of messages political actors receive on the election day and the week after (see Table 6.5). Additional content analysis needs to shed light on the relation between this quantitative upsurge of inter-group communication and the content of the messages.

3 Discussion

Based on a two-fold study on Twitter use during election times, we aimed to reveal intermedia and inter-agenda connections. A close reading of the content materials that are shared and the relations between the actors in the debate allows us to put forth some concrete theoretical and methodological insights.

Agenda setting is one of the main perspectives in mass communication and political communication effect research (McCombs 2004). The theory matured to also include shared news agendas among different media, or intermedia agenda setting, as is at stake here. Via the analysis of two Twitter conventions, i.e. hashtags and hyperlinks, we understand Twitter’s embeddedness in the broader media ecology. The high number of links to other social media platforms (and audio-visual content), suggests affective and social aspects of the communications are relevant in addition to (or instead of) the emphasis on cognitive aspects of the communication process, notably attention and understanding. Relative to it, Meraz (2011) points to links between agenda setting processes and social influence theories to better understand these networked media environments. Links between mainstream media outlets and the Twitter platform are complicated by the presence of traditional media outlets in it. Although we assessed relations between content and users separately, further studies preferably link the content or conventions of the messages (i.e. hashtags and hyperlinks) with user information.

The network analysis of direct interaction patterns between users provides interesting findings concerning the platform’s promises of open and equal interaction flows. Although we did not discuss the content of the messages, research indicated that content with @signs reflects more interactive messages, more likely to activate or influence others (Honeycutt and Herring 2009). In this respect, network theories and measures are relevant in the context of agenda setting research as well. In this particular context of hashtag research, one can exceed the established network of follower and followees, resulting in new connections (Bruns and Burgess 2011). The (possible) connection of otherwise unconnected ties might link up to the high number of weak ties that were found in the network. In addition, the central positions of established elites can be linked to their visibility in other media.

We can conclude that citizen users’ position in the network does not represent a shift in traditional power hierarchies and elite domination. Concerning the different periods we demarcated, we notice small differences in in-degree centrality of the actor types and large differences in reciprocity and out-group communication between pre-election and (post-) election periods. These structural differences can be first indicators of different flows of content or influence between the media and political agenda and public opinion. For a more valid and in-depth understanding, we obviously need to take into account the content of the messages as well. In addition, more qualitative methods on the appropriation of ‘@signs’ by Twitter users are at stake here as well. Potential questions for additional validation are: do addressivity markers always reflect interaction or is it contingent on the type of actors to which these messages are addressed? Do people expect responses when they address particular actors or do they just want to make visible what they are writing about a particular actor?

To conclude, we would like to stress the particularity of heightened political periods such as the elections. In addition, the specific characteristics of the election context suggests precaution towards the generalization of the findings to other countries and elections.

Notes

- 1.

Gawk scripts allow the identification and filtering of data, e.g. hashtags, URL’s or ‘@reply messages’. http://mappingonlinepublics.net/tag/gawk/.

- 2.

ia the software program for social network analysis UCINET, the main component or largest collection of connected nodes can be extracted for a set of interactions. This reduces the data to feasible amounts for manual analysis without the loss of important data. For example for the first research period, 848 out of 1,173 actors were retained for further analysis, indicating that most of the data is retained.

- 3.

For each period, the category ‘other’ is left out of the analysis of the interaction patterns. Via UCINET, we extracted network relations between media actors, political actors and citizens.

- 4.

In UCINET, an Anova analysis was conducted for indegree and outdegree differences between media, political and citizen actors. F-statistics per period: (1) 18.63 (2,797), p < 0.001, (2) 19.31 (2,457), p < 0.001, (3) 37.55 (2,791), (4) 27.37 (2,750), p < 0.001.

- 5.

The exact levels of dyad-based reciprocity per period: (1) 3.38 %, (2) 2.22 %, (3) 4.3 %, (4) 1.9 %.

- 6.

The E-I index is calculated as following: [number of ties external to the group minus the number of ties that are internal to the group] divided by [the total number of ties]. The values range from −1 (all ties are internal) to +1 (all ties are external).

References

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks. How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58, 707–731.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Freeman, L. C. (2002). Ucinet for windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, wikipedia, second life and beyond. New York: Peter Lang.

Bruns, A. (2012). How long is a tweet? Mapping dynamic conversation networks on Twitter using Gawk and Gephi. Information, Communication & Society, 15, 1323–1351.

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011). #Ausvotes: How twitter covered the 2010 Australian federal election. Communication, Politics and Culture, 4, 37–56.

Chaffee, S. H., & Metzger, M. J. (2001). The end of mass communication? Mass Communication and Society, 4, 365–379.

Coleman, S. (2003). A tale of two hourses: The house of commons, the Big Brother house and the people at home. Parliamentary Affairs, 56, 733–758.

Curran, J., Fenton, N., & Freedman, D. (2012). Misunderstanding the Internet. New York: Routledge.

Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. M. (1996). Agenda setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Deller, R. (2011). Twittering on: Audience research and participation using Twitter. Participations, 8, 216–245.

Elmer, G. (2012). Live research: Twittering an election debate. New Media & Society, 15, 18–30.

Epping, L., De Smedt, J., Walgrave, S., et al. (2013) Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen 2012: Er werd vooral over de N-VA gesproken. Media-aandacht voor politici in de gemeenteraadsverkiezingsprogramma’s van 2012 op de VRT. Het Steunpunt Media.

Fenton, N. (2012). The internet and social networking. In J. Curran, N. Fenton, & D. Freedman (Eds.), Misunderstanding the internet (pp. 123–148). New York: Routledge.

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hermans, L., & Vergeer, M. (2012). Personalization in e-campaigning: A cross-national comparison of personalization strategies used on candidate websites of 17 countries in EP elections 2099. New Media & Society, 15, 72–92.

Hermida, A. (2010). Twittering the News: the emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice, 4, 297–308.

Honeycutt, C. & Herring, S. C. (2009). Beyond Microblogging: Conversation and collaboration via Twitter. Forty-Second Hawai’i International Conference on System Sciences. Los Alamitos, CA.

Larsson, A., & Moe, H. (2012). Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedisch election campaign. New Media & Society, 14, 729–747.

Lewis, S. C., Zamith, R., & Hermida, A. (2013). Content analysis in an era of big data: A hybrid approach to computational and munual methods. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57, 34–52.

McCombs, M. (2004). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Meraz, S. (2011). Using time series analysis to measure intermedia agenda setting influence in traditional media and political blog networks. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 88, 176–194.

Papacharissi, Z. (2009). The virtual geographies of social networks: A comparative analysis of Facebook, LinkedIn and ASmallWorld. New Media & Society, 11, 199–220.

Prior, M. (2006). Post-broadcast democracy: How media choice increases inequality in political involvement and polarizes elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-democracy. Politics in an age of distrust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, J. B. (2014). User-generated visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space. New Media and Society, 16(1), 55–73.

Skovsgaard, M., & Van Dalen, A. (2013). Dodging the gatekeepers? Social media in the campaign mix during the 2011 Danish elections. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 737–756.

Van Aelst, P. (2008). De lokale verkiezingscampagne: tussen huisbezoek en televisiestudio. In J. Buelens, B. Rihoux, & K. Deschouwer (Eds.), Tussen Kiezer en hoofdkwartier. Brussel: VUBPRESS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

D’heer, E., Verdegem, P. (2014). An Intermedia Understanding of the Networked Twitter Ecology. In: Pătruţ, B., Pătruţ, M. (eds) Social Media in Politics. Public Administration and Information Technology, vol 13. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04666-2_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04666-2_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-04665-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-04666-2

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)