Abstract

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, policymakers at both global and national levels have begun to implement a range of regulatory measures designed to address systemic risk more consistently. One of the key elements of this has been a framework to contain the moral hazard and the negative externalities related to systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Regulators are seeking to make these institutions more resilient and to avoid future defaults. Another line of defense in this context is a more efficient restructuring and resolution regime. Against this backdrop, there has been increased interest on the part of policymakers in quantitative indicators measuring systemic importance. Based on indicator categories proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) we illustrate how, in principle, a set of indicators like this can be used to monitor the development of banks’ systemic importance over time. Overall, the set of indicators suggests that the systemic importance of large German banks has declined somewhat over the last 4 years. This finding appears to be driven mostly, however, by factors other than new policies directly addressing the too-important-to-fail-problem, chiefly the difficult economic environment. Therefore, it is still too early for a final judgment on the effectiveness of such policies. Given that credit rating-based measures of systemic government support suggest that large German banks are still benefitting from a substantial public subsidy, it may be necessary to consider additional policy measures over the medium term.

The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or its staff. Thilo Liebig is Head of the Macroprudential Analysis Division in the Financial Stability Department of the Deutsche Bundesbank and Sebastian Wider is a senior economist in the same division.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 The Systemic Scale of the Banking Crisis and the Regulatory Response

The events of the crisis year 2008 resulted in a broad global consensus among the relevant policymakers to reform the supervisory and regulatory framework, in particular, by addressing systemic risks more consistently. The same large, complex financial institutions that had been operating much like proud sailing vessels, travelling the market seas in a period of fair weather as the flagships of sophisticated risk management proved to be surprisingly vulnerable when their fleet navigated into the hurricane of financial turbulence. Some of them sank – their oversized sails exposed them to the storm and they had stored too little capital and liquidity as counterweights in their keel – and many came close to capsizing. During 2008 it became increasingly evident that financial institutions’ risk management systems and the available liquidity and capital buffers in this sector were not adequate for preventing a disorderly downsizing of the global financial system. Private sector crisis management options, such as mooring weaker banks to stronger institutions (e.g. by takeovers), became more and more exhausted when large and complex banks themselves needed help. In order to restore confidence and contain the crisis with its negative impact on the real economy, central banks and governments implemented comprehensive stabilization measures. In addition to the significant liquidity provision of the European System of Central Banks, the German government set up a Financial Market Stabilization Fund (SoFFin) in mid-October 2008. This included government guarantees of up to €400 billion for bank liabilities, and funds for capital injections and asset purchases of up to €80 billion. The draft law on which the SoFFin was established also pointed out that the government would take care of the Pfandbrief, if needed, in order to avoid any defaults in this specific funding instrument in the future (Deutscher Bundestag 2008). On October 5, Chancellor Merkel and Finance Minister Steinbrück had already issued a political declaration assuring the German public that the government would not allow a crisis at one bank to become a crisis for the system as a whole, and provided a guarantee for every euro in retail deposits at German banks. In addition to the measures of the federal government, public sector resources were also committed at the level of the German states to stabilize some vulnerable Landesbanken.

These measures, taken all together, indicate the systemic scale on which German banks were drawn into the international banking crises, with large banks being the most exposed as well as the most interconnected. This meant that shocks hitting these banks had the potential to spread through a complex network of counterparties, creditors and markets. Against this backdrop, policymakers made it very clear from the outset that the extraordinary stabilization efforts would only be one leg of the policy response – the other leg would be a stricter regulatory framework. The internationally coordinated reform agenda would not only correct failures in the pre-crisis framework in a backward-looking manner, it would also seek to prevent the build-up of new systemic risks in the future. Among other causes of the crisis, it would specifically address moral hazard problems, which were identified as a flaw in the originate-to-distribute-model as it was practiced in the U.S. private-label securitization market. More generally, there are strong theoretical arguments that moral hazard can be a driver of excessive risk-taking, pro-cyclical leverage in the financial system and an increasing size and complexity of financial institutions, given that these can capitalize on the perception of an implicit government guarantee (see, for example, Dam and Koetter 2011). Hence, addressing moral hazard problems more decisively than before the crisis has been motivated to a major extent by the objective of giving better protection to public finances and counteracting market participants’ expectations that the extraordinary stabilization measures taken by the public sector can be relied upon as a permanent subsidy. With this in mind, the G20-Leaders’ Declaration for the Pittsburgh Summit in September 2009 stated,

We committed to act together to raise capital standards, to implement strong international compensation standards aimed at ending practices that lead to excessive risk-taking, to improve the over-the-counter derivatives market and to create more powerful tools to hold large global firms to account for the risks they take. Standards for large global financial firms should be commensurate with the cost of their failure.

2 Reducing the Probability of a SIFI Default

Since then, noticeable progress has been made in translating and operationalizing these political declarations into a concrete regulatory framework. At the international level this work has been coordinated by the Financial Stability Board (FSB). Large, complex banks are subject to the regulatory reforms that apply to all banks, such as capital requirements, liquidity standards and restrictions on large exposures. However, two strands of policy initiatives can be distinguished which specifically address the too-important-to-fail problem. One approach is primarily directed at reducing the probability of a SIFI default. Most visible has been an official list of 29 global systemically important banks, which the FSB published for the first time in November 2011. The initial list included two banks with headquarters in Germany, of which one lost its status as a global SIFI when the list was updated in November 2012. Institutions in this list are required to have additional loss absorption capacity in the form of a capital surcharge between 1 % and 2.5 % of risk-weighted assets (which could be up to 3.5 % for the hypothetical case of even more systemically important institutions). Starting in January 2016, these requirements will be phased in with full implementation by January 2019.

A reduction in the probability of default is a very practical approach with regard to large banks with cross-border activities in order to internalize potentially negative cross-border externalities and to mitigate the remaining uncertainty about the effectiveness of a joint international crisis management approach. In principle, however, it is also possible for national authorities to extend this capital based policy tool for large, complex banks with key functions in the domestic financial system, but which are not included in the global SIFI list. While capital-based policy measures can be expected to strengthen the resilience of a SIFI, it will, of course, depend on a number of other factors whether they discourage institutions from engaging in those operations and business structures that are the main drivers of their SIFI status. Complementary to higher capital requirements, a range of supervisory activities regarding large, complex institutions are being intensified, too. This comprises international teams of supervisors (colleges), higher standards with regard to risk assessment, rigorous stress testing and more comprehensive risk-related data requirements.

3 Effective Bank Restructuring and Resolution Frameworks

The other strand of policy initiatives is directed at making possible the orderly restructuring or resolution of a failing SIFI. As a side effect, this is also having a beneficial impact on the default probability of SIFIs, given that a credible default option would tend to strengthen market discipline and moderate the risk-taking behavior of the bank management. Consequently the build-up of major vulnerabilities might be prevented. However, an effective resolution framework for financial institutions is an intermediate policy objective in itself in order to make crisis management more efficient, avoid negative externalities and to minimize contingent financial claims on the public sector. In October 2011, the FSB published the “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions”. In the absence of a globally uniform insolvency law the document sets out, for the first time, essential features that are recommended to be integral parts in the resolution regimes of all jurisdictions. International implementation could lead to a gradual alignment of the diverse national legal frameworks. Among other features, the FSB’s “Key Attributes” include legal powers and tools to enable creditor-financed bank recapitalization. For the group of global SIFIs, as a minimum, the document stipulates mandatory recovery and resolution planning as a means to identify overly complex banking structures and other obstacles. Furthermore, it stipulates cross-border groups comprising public authorities that would be involved in crisis management, institutions-specific international cooperation agreements and regular resolvability assessments. Another complementary measure worth mentioning in the context of restructuring and resolutions frameworks is the implementation of stricter requirements for OTC derivatives transactions. Mandatory central clearing and higher requirements for capital and collateral are expected to significantly reduce the contagion risk from counterparty exposures in the highly concentrated OTC derivate markets. Interconnectedness between banks with large, complex derivate activities is therefore likely to become less of an obstacle to effective restructuring and resolution.

Considering the vast cross-border activities of many banks over the past 20 years, it may be tempting to ask why initiatives for more international harmonization and cooperation had to wait for the crisis to act as a catalyst.Footnote 1 And yet, despite the noticeable progress that has been achieved, a solution is still needed for sensitive issues such as the moderation of conflicting interests or assessments of how to deal with an internationally active bank in a specific crisis situation. The economically less than perfect practice in the past was to ring-fence the assets of banks in distress and break financial groups up according to national boundaries or to have them rescued as separate national entities by the respective home states. The current approach of national frameworks, however, cannot fully overcome such cross-border issues. National rules have limited scope with regard to the foreign legal relationships of agents.

To some extent, this is also a shortcoming of the German Bank Restructuring Act, which entered into force in January 2011, already anticipating elements of the FSB framework and preceding forthcoming EU initiatives which seek to enable coordinated crisis management action with the responsible authorities across borders. The German Bank Restructuring Act has a number of noteworthy features (see Deutsche Bundesbank 2011). First, there is greater legal certainty for German supervisory authorities to intervene early. Supervisors can order institutions to present a restructuring plan. Second, authorities are given legal clarity that, in a reorganization procedure, if necessary, there can be interventions into third party rights. For example, the institution’s liabilities may be deferred or reduced and debt-equity swaps or spin-offs of some or all assets are also possible. Thus, a powerful instrument has been added to the prudential toolkit, allowing supervisors to order the transfer of systemically important assets and liabilities to another legal entity. Third, the Act is setting up a Restructuring Fund, which is owned by the federal government, but contributions are made through a banking levy on all credit institutions, which is based on a progressively rising function of simple measures of size and interconnectedness. Although it is only one element of the broader regulatory agenda to address the too-important-to-fail-problem, the German Bank Restructuring Act has had an observable impact. For example, in February 2011 the Bloomberg website reported that the credit ratings for a number of German banks’ debt securities had been downgraded by Moody’s, based on the expectation of materially reduced government support. From a policymaker’s perspective, such a revision of market participants’ perception of German banks’ creditworthiness is positive, given that the policy intention of providing only temporary support to the banks amid a global financial crisis is seen as credible. The Bank Restructuring Act seems to have been a step in the right direction in terms of strengthening market discipline and incentivizing banks to substitute reduced government support by adjusting their balance sheets and business models.

The political initiative for a banking union has since opened up the way to addressing the problem of cross-border SIFI resolution in Europe even more efficiently. A European resolution authority and ex ante rules for burden sharing in Europe can be useful complements to the Single Supervisory Mechanism, which puts the ECB in a position to supervise all systemically important banks in the euro area. However, the benefits of this initiative will ultimately depend on broad political support, a sound legal basis and effective operational structures; all of this is still in a state of flux.

4 Indicators for Systemic Importance

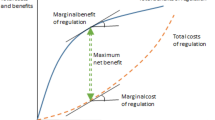

Substantial work has been performed in identifying and measuring systemic importance at the level of individual institutions, often in the background of G20 summits and the international regulatory reform agenda. Although the too-important-to-fail problem is often categorized as being part of the structural dimension of systemic risk in the financial system, it has a time dimension, too. Monitoring the change in measures of financial institutions’ systemic relevance is an essential element in the calibration of prudential policies, in the ongoing impact assessment of these policies, and in the process for identifying the build-up of new systemic risks. The up-to-date information resulting from the continuous monitoring of these indicators also provides policymakers with valuable data in an acute crisis management situation, when it is important to gauge what likely impact distress at a given firm will have on the stability of the system as a whole. For example, the FSB’s list of global SIFIs – primarily used to allocate the capital surcharges – adopts an indicator-based measurement approach proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and builds on earlier studies such as IMF/BIS/FSB (2009). With regard to the alternative of model-based methodologies, it is noteworthy that the BCBS came to the conclusion that

[…] models for measuring systemic importance of banks are at a very early stage of development and there remain concerns about the robustness of the results.

Table 1 shows the five indicator categories for different dimensions of systemic importance as well as some examples of specific indicators. In the second part we illustrate how, in principle, a set of indicators like this can be used to monitor the development of banks’ systemic importance over time. However, at this stage the methodology does not allow us to analyze the drivers of the indicator change in more detail, for instance, to quantify the relative contributions made by changes in the regulatory environment or by macro-economic variables. Greater differentiation would be needed in the context of a comprehensive policy impact assessment. For the time being, rigorous quantitative analysis has to be replaced with some qualitative judgment. Overall, the set of indicators suggests that the systemic importance of large German banks has declined somewhat over the past 4 years. This reflects the fact that the banks have been sailing in rough seas ever since the financial hurricane of 2008. The waves have been coming in from both sides: banks’ balance sheets and some business models have been intentionally put under salutary pressure from the regulators, while, at the same time, the adverse economic environment, namely the persistent sovereign debt crisis in the euro area, has been a major dampening factor on risk-taking. But banks, too, have been benefitted from accommodative central bank policies and continued support by public emergency backstops in the form of guarantees and capital injections.

So far, the indicators of systemic importance appear to be driven mostly by factors other than new regulations directly addressing the too-important-to-fail-problem. This finding does not imply that the policies are ineffective: it should be borne in mind that not all of them have been fully implemented yet and that their effectiveness may become more noticeable in the upswing of a financial cycle, when they dampen the resurgence of systemic risks related to SIFIs. In terms of risk-bearing capacity the group of large German banks has become more resilient (see Deutsche Bundesbank 2012). But a continuously vigilant monitoring of “systemic importance” is warranted. After all, credit rating agencies still attribute typically 2–3 notches of large German banks’ issuer ratings to the expectation of systemic support provided by the government.Footnote 2 This kind of rating uplift, which is also evident for a number of banks in other jurisdictions, might be associated with a funding advantage, implying a considerable public subsidy for large banks (see, for example, Ueda and Weder di Mauro 2012). From a policy perspective, this is hard to justify in the long run.

5 Monitoring Selected Indicators for Large German Banks

5.1 Size

The ratio of bank assets-to-GDP is often used as a simple measure of financial deepening and it can be argued that there is a positive relationship between large, efficient banks and countries’ economic growth over the medium term. For example, global financial deregulation in the early 1980s, together with technological progress such as computerization, allowed large banks to launch new products and diversify risks more broadly. Today, “plain vanilla” interest rate swaps, currency swaps and large, internationally diversified credit portfolios are usually not seen as a specific risk to financial stability, although they have contributed to the growth of banks’ balance sheets.Footnote 3 However, the existence of some economies of scale does not necessarily lead to the general conclusion that size is positive, in particular, in combination with complexity, interconnectedness and low substitutability. Bearing in mind the public costs of stabilizing the large banks in Germany and the losses of confidence as well as of output that resulted from the negative spill-over to the real economy, the burden of proof has been put on the banks to show in their own restructuring and resolution planning that size is manageable.

The BCBS’s preferred size indicator is “total exposures as defined for use in the Basel III leverage ratio”. This indicator comprises both on-balance sheet items and off-balance sheet items, with the latter representing 30 % of some institutions’ exposure. Hence, among other items it contains information about the gross value of securities financing transactions and the exposures of derivative contracts. As a proxy that is already available for a larger group of German banks and also before 2010, when the BCBS initiated the compilation of global SIFI data for the first time, we use data from the monthly reports submitted to the Bundesbank pursuant to Sect. 25 (2) of the German Banking Act (Kreditwesengesetz KWG).

In contrast to the increasing financial deepening of earlier decades, the data show that, after 2008, total assets of this group of 12 large banks in Germany were in a period of stalemate. Following a crisis-driven deleveraging in 2009, total asset growth has been broadly in line with domestic nominal GDP since 2010. Relative to GDP, the less volatile claims on non-banks, such as bank loans to households and businesses, have even been lagging behind. This is consistent with weak credit demand and a selective retreat from some markets, amid economic downturns in other European countries. Moreover, the European Commission, which is responsible for cross-border competition policies, required some large banks in Germany to actively shrink their balance sheet after receiving state aid.

Remarkably, the slowdown in the large German banks’ claims on non-banks has been achieved in an orderly manner without overshooting to the other extreme of a “credit crunch” with severe credit supply constraints for the real economy. And yet, the overall high level of total bank assets would suggest the persistence of the SIFI problem if it were not possible to identify significant structural adjustments under this surface towards greater resilience, business models that are more sustainable and fewer potentially negative externalities. In this regard, one major element is the strengthened capital position. For the group of 12 banks, the average tier 1 ratio increased from just above 8 % of risk-weighted assets in early 2008 to over 13 % in 2012 (Deutsche Bundesbank 2012).

5.2 Cross-Jurisdictional Activity

Large German banks have been playing a significant role in cross-border banking activities for many years, partly reflecting the export-orientation of the German economy.Footnote 4 The marks of international integration can be found in the banks’ assets and in their funding as well as in their network of foreign branches and subsidiaries. On the one hand, this has exposed them to shocks from other countries and, furthermore, accentuated the difficulty of coordinating their resolution if these banks become distressed and when crisis management by the German authorities potentially has serious economic implications for other economies, too. For example, countries where German banks hold a significant market share might suffer from an abrupt retreat of liquidity and credit supply. On the other hand, there are significant benefits stemming from international capital flows and the diversification opportunities available to German banks, which should be preserved Fig. 1.

Recently, the unwelcome fragmentation of banking activities along national borders – even within the euro area – has been dramatically highlighting what may be at stake if the financial system were to continue unwinding its cross-border activities. The preferred policy approach to the too-important-to-fail problem, therefore, would certainly not be active intervention in banks’ international activities by downsizing them across the board. Rather, the preferred policy approach consists once again in a combination of reducing the default probability of banks – which might imply a review of capital requirements for the more risky cross-border activities – and greater international cooperation and harmonization among supervisors, regulators, and resolution authorities as well as within the legal framework.

The data on total foreign claims of German banks indicates a significant correction during the financial crisis in 2009. In this first global deleveraging phase, asset reductions concentrated on US dollar securities and short-term interbank loans. In contrast to this episode, German banks’ claims vis-à-vis European countries with stressed sovereign bond markets have generally not been reduced via fire sales, but were instead held to maturity after the sovereign debt crisis escalated in 2010. A similar orderly declining trend is evident from the data on the securities held by the group of 12 large banks in Germany. These securities portfolios have national and international securities in them. Considering regulatory requirements and future business opportunities, banks might have been prioritizing loans and the associated customer relationship over credit exposures through securities.

Banks operate in a network with other financial institutions. The connections in the network can be interbank loans, repurchase agreements, securities lending or OTC derivatives transactions and holdings of securities issued by other banks. A default of a highly interconnected participant in the network can be difficult to manage without triggering a chain reaction in the network. There is a trade-off similar to the cross-jurisdictional activities. On the one hand, a highly interconnected network can be efficient, for example, in allocating liquidity, capital and risks. On the other hand, it can increase the risk of contagion between the participants. Counterparty risk mitigation through collateral, capital, liquidity and risk concentration limits is part of finding a practical solution in this trade-off. Moreover, compiling more detailed network data and systematically analyzing it could become an important tool for supervisors in terms of identifying systemic risks and potential second-round effects at an early stage (see IMF/BIS/FSB 2009).

In the not so distant past, international securities portfolios were purchased by some German banks as a substitute for weak domestic credit demand amid a liquidity glut (Kreditersatzgeschäft). For many banks, this search for yield in securitized credit products resulted in disproportionate losses. For supervisors, it would be at least a warning signal if, in the current low yield environment, banks were again chasing a particular class of securities Fig. 2.

5.3 Interconnectedness

The aggregated data of interbank loans and (reverse) repurchase agreements in Fig. 3 indicates a substantial contraction in the network in 2008 and 2009, driven by counterparty risk concerns, a substitution of interbank markets by central bank funding and deleveraging pressures. While, initially, this contraction was enforced by market mechanisms, regulatory changes will have a more permanent impact on the evolution of future networks. New limits on interbank exposures have been implemented (25 % of the capital base vis-à-vis a single entity) and specific capital plus liquidity requirements are making interbank loans more resilient. However, the interbank market in the euro area is persistently afflicted by counterparty risk concerns and some European banks are resorting to central bank funding in unusual amounts. The regulatory toolkit cannot cure the root causes of this problem. It is the responsibility of politicians to avoid tail events that cannot be absorbed, even after the banking network in Europe has been made more resilient.

5.4 Substitutability/Financial Institution Infrastructure

The BCBS’s measurement approach to the substitutability problem explicitly refers to assets under custody, i.e. holding assets on behalf of customers, payments cleared and settled through payment systems, and values of underwritten transactions in debt and equity markets. However, the same reasoning can be applied to other market segments and client services provided by the banks, for example, lending to small and medium-sized enterprises and deposit taking. With a dominant market share, it is expected that a bank failure will be followed by disruptions and that a large number of customers will simultaneously have the cost of finding another service provider. For the assessment of these measures of systemic importance, and in order to derive the market share of a specific institution, it is necessary to define the relevant market and alternative service providers in each segment. Overall, we are not aware of major structural changes in the systemic importance of the large German banks in this regard, although, from a cyclical perspective, the value of assets under custody has increased noticeably from its trough after 2009.

5.5 Complexity

The final indicator category comprises measures of business, structural and operational complexity, potentially driving up the costs and the time needed to resolve a bank. There are three examples: first, OTC derivatives; second, “level 3” assets, whose fair value cannot be determined using observable measures; third, securities held “for trading” or “available for sale”. The BCBS’s rationale for using this kind of securities as indicators of systemic importance, are the potential spillovers through mark-to-market losses and fire sales.

With regard to German banks’ activities in the OTC derivatives markets, the data in Fig. 4 reflect the dynamic expansion of the risk transfer markets over more than a decade. OTC derivatives are privately negotiated contracts, which can be customized. The risk management for these – sometimes complex and illiquid – products can be very challenging. Remarkably, the recent decline in notional amounts outstanding – supposedly reflecting a compression of positions with central counterparties (CCPs) as well as less hedging and trading demand – could foreshadow the implementation of a regulatory regime shift in this market.

In the light of the crisis experience with the complex derivatives portfolios of institutions such as Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and American International Group, policymakers in the United States, in Europe and other relevant jurisdictions decided to make the central clearing of standardized derivatives mandatory. The use of CCP can effectively eliminate a key source of counterparty risk between SIFIs, and thus systemic risk, provided the CCPs risk management is sound. Moreover, capital and collateral requirements for exposures to derivatives have been increased. Reporting obligations to trade repositories will also bring more transparency to the opaque OTC derivatives markets. And yet, despite these coming fundamental changes, the future role of the SIFIs should be closely monitored. SIFIs may find ways to secure their dominant position in new networks. If the product is no longer customized OTC derivatives, it could be collateral transformation services instead, given the increasing demand for collateral extends to customers. Then, it would be the collateral transfer network that re-establishes a higher degree of interconnectedness. For regulators, there may be practical limits to reducing complexity permanently.

Conclusions

Based on the set of indicators, we find a moderate reduction in the systemic importance of large German banks since 2008. However, not all the policies addressing the too-important-to-fail problem have been fully implemented yet and their effectiveness may become more noticeable in the upswing of a financial cycle, when they dampen the resurgence of systemic risks related to SIFIs. At the same time, it is understandable that some policymakers are pointing to the overall persistently high level of systemic importance of SIFIs and demanding further action.

In Germany, a kind of “bank-separation act” is scheduled to come into effect in January 2014, following the entry into force of German legislation to implement the EU’s Capital Requirements Directive IV (Bundesfinanzministerium 2013). Separation of business activities within banks should then be carried out by July 2015. The first part of this act includes a tool that was agreed internationally at the October 2011 meeting of the FSB: mandatory “living wills” for banks. As a result, supervisors will be able to demand the elimination of obstacles to resolution which have been identified in the banks’ own planning. The second part actually gives the bill its name: bank separation act. It stipulates that if certain thresholds are exceeded, deposit-taking credit institutions will have to spin off proprietary trading and prime brokerage services into a company that is legally, economically and organizationally separate. The third part introduces criminal-law provisions for the bank’s management. On the positive side, this act makes bank resolution more credible by removing organizational obstacles and possibly creating smaller entities. Basically, the idea is to build banking “ships” that do not sink in a storm. Even if – in the investment banking operations – the rig is torn and the mast is broken, a robust ship hull – holding the deposits and loans – can be used as a rowing boat. In practice, it is not so easy, of course, to determine the specific banking activities that should be separated from the deposits. In particular, investment banking services for non-financial corporates can have a dual use. Moreover, even if there are clearly separated entities, pure investment banks may still be perceived as too important or too complex to fail. And there are examples of deposit-takers with seemingly simple business operations that accumulated excessive risks, typically in real estate loans or interest rate risk positions.

Against this backdrop, national bank separation acts are one regulatory tool worth considering, but, ultimately, they are not a substitute for closer international cooperation. The solution of the SIFI problem should avoid cross-border financial fragmentation and giving up the benefits of international capital flows. In other words, it is necessary to have ships that are large and robust enough to cross the seas, since otherwise, trade will be confined to inland waters.

Notes

- 1.

As a paper by Völz and Wedow (2009) implies, it would have been possible – even before 2008 – to find evidence in CDS spreads suggesting that banks’ size distorted market prices.

- 2.

Source: Company Websites.

- 3.

For a deeper analysis see, for example, Düllmann and Puzanova (2011). They find some empirical evidence that size alone is not a reliable proxy for the systemic importance of a bank.

- 4.

See Buch et al. (2010) for empirical evidence that this can be a mixed blessing for the banks themselves.

References

BCBS (2011) Global systemically important banks: assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement. http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs207.pdf and http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs255.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Bloomberg (2011) German Bank subordinated debt downgraded by Moody’s on regulation concern, 18 Feb 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-02-17/german-bank-debt-securities-totaling-33-billion-cut-by-moody-s-on-risks.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Buch CM, et al (2010) Do banks benefit from internationalization? Revisiting the market power-risk nexus. Deutsche Bundesbank discussion paper, series 2: banking and financial studies, no 09/2010

Bundesfinanzministerium (2013) German government approves draft bank-separation law and new criminal-law provisions for the financial sector, 6 Feb 2013. http://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2013/2013-02-06-german-government-approves-draft-bank-separation-law.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Dam L, Koetter M (2011) Bank bailouts, interventions, and moral hazard. Deutsche Bundesbank discussion paper, series 2: banking and financial studies, no 10/2011

Deutsche Bundesbank (2011) Fundamental features of the German Bank Restructuring Act, Monthly Report, June 2011

Deutsche Bundesbank (2012) The German banking system five years into the financial crisis, Financial Stability Review, Nov 2012, p 37. http://www.bundesbank.de/Redaktion/EN/Downloads/Publications/Financial_Stability_Review/2012_financial_stability_review_print.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Deutscher Bundestag (2008) Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Finanzmarktstabilisierungsgesetz (FMStG), Drucksache 16/10600, 14 Oct 2008, p 9. http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/16/106/1610600.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Düllmann K, Puzanova N (2011) Systemic risk contributions: a credit portfolio approach. Deutsche Bundesbank discussion paper, series 2: banking and financial studies, no 08/2011

FSB (2011a) Key attributes of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions, Oct 2011. http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111104cc.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

FSB (2011b) Policy measures to address systemically important financial institutions http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111104bb.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

G20 (2009) Leaders’ statement the Pittsburgh Summit, 25 Sep 2009. http://www.g20.org/documents/final-communique.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

IMF/BIS/FSB (2009) Guidance to assess the systemic importance of financial institutions, markets and instruments: initial considerations, Oct 2009. www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_091107c.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2013

Ueda K, Weder di Mauro B (2012) Quantifying structural subsidy values for systemically important financial institutions, IMF working paper no 12/128

Völz M, Wedow M (2009) Does banks’ size distort market prices? Evidence for too-big-to-fail in the CDS market. Deutsche Bundesbank discussion paper, series 2: banking and financial studies, no 06/2009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Liebig, T., Wider, S. (2013). SIFIs in the Cross Sea: How Are Large German Banks Adjusting to a Rough Economic Environment and a New Regulatory Setting?. In: Maltritz, D., Berlemann, M. (eds) Financial Crises, Sovereign Risk and the Role of Institutions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03104-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03104-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-03103-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-03104-0

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)