Abstract

This chapter presents three approaches to supporting undergraduate and postgraduate students in the development of their academic literacy. The approaches were designed and evaluated as part of a writing development project which aimed to move away from the predominantly generic and unequally distributed provision of writing instruction at UK universities. In view of various writing theories, one objective of the project was to find a balance between text-focused instruction and the development of students’ critical awareness of the academic culture and practices of their disciplines and the wider academic context. Another objective was to explore to what extent subject lecturers need to be involved in teaching literacy. The evaluation showed that literacy instruction without the input of subject lecturers can be ineffective. Furthermore, the results revealed that novice writers are not prepared to take a critical perspective of literacy practices and are mainly interested in accommodating to the writing conventions in their discipline. This finding contradicts the postulations of some models that writing instruction should focus less on text and more on challenging practices and conventions. The preliminary conclusion is that the analysis of texts and genres specific to the discipline is the best starting point for students’ acculturation into academic literacy. The third approach discussed in this chapter gives an example of how subject lecturers and writing experts can collaborate to help students to understand the text and genre requirements in their discipline.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In this chapter, I discuss three approaches to develop the academic literacy of students in mainstream higher education in England. These approaches were the outcome of a writing development project that was carried out at King’s College London between 2006 and 2011. The project was based on the understanding that a narrow focus on writing and texts would not be sufficient but that a wider perspective was needed to support students’ acculturation into academic literacy. By acculturation I mean knowledge and understanding of the academic practices and literacy requirements of (a) the discipline (e.g. epistemology and conventions), (b) the university (e.g. assessment policies), and (c), particularly in the case of international students, of the Anglophone context. Therefore, the project aimed to provide students with insights and opportunities for the process of acculturation.

The need to pay attention to the surrounding academic culture and practices has been repeatedly stressed by theorists from Academic Literacies (e.g. Lillis 2003; Lillis and Scott 2007) and Critical English for Academic Purposes (EAP) (e.g. Benesch 2001, 2009). The related academic debate is reported in Sect. 3. However, so far there is little evidence of pedagogical applications, nor much advice on how and to what extent issues concerned with academic culture and practices should be integrated into the writing curriculum. The writing development project made a first step towards providing such evidence. The teaching approaches created in the project included various elements intended to raise students’ awareness of academic practices. The effectiveness of these elements and students’ acceptance of them were investigated in the project. Another issue was to what extent subject lecturers should be engaged in the teaching of academic literacy. It has been strongly argued that subject specialists must take responsibility for development of students’ writing (particularly by the movement ‘Writing in the Disciplines’, see Deane and O’Neill 2011). As representatives of the discipline’s and institution’s culture, and experts in the associated discourses and conventions, they are best positioned to support students’ acculturation. However, as discussed in the next section, this responsibility is often shifted to others in the English higher education context.

The three approaches to teaching academic literacy were developed subsequently and build on each other. The evaluation results of earlier approaches led to changes in the theoretical and pedagogic approach of the later ones. Thus, the project reflects a process of learning about effective ways of acculturating students into academic literacy, and in this chapter I want to share some insights from this learning process.

2 Background

The writing development project reported here is one of several which were initiated at English universities in response to the rapidly changing higher education landscape and the growing realisation that existing student support is insufficient and outdated. Until the early 1990s, higher education in England was an elite system in which students were expected to arrive at university with adequate literacy competence. Only in the last 15 years has the number of ‘non-traditional’ students (from social groups that have traditionally not participated in higher education) and international students substantially grown. Despite the fact that these student groups need more help with academic literacy, the provision of support has hardly changed from the previous highly selective system. It still consists mainly of generic English language courses for international students, usually offered in Language Centres exclusively to non-native speakers, and some limited study skills advice for native speakers (home students), usually offered in learning development units (Ivanic and Lea 2006; Wingate 2006). Both types of provision have fundamental conceptual flaws. First, writing is taught by writing specialists or learning developers outside the disciplines, detached from subject content. This generic approach ignores the fact that students’ problems with writing are less of a linguistic nature, but mainly caused by a lack of understanding of how knowledge is constructed, debated and presented in specific disciplines (Lea and Street 1998). A second flaw is the distinction between native and non-native speakers of English which ignores that both groups are novices in reading, reasoning and writing in an academic discipline. Any approach that excludes certain groups of students is therefore inappropriate in today’s higher education context (Wingate and Tribble 2012).

The instructional approaches presented in this chapter therefore targeted the ‘mainstream’ rather than specific student groups. Accordingly, two main principles proposed by the model ‘Writing in the Disciplines’ (Monroe 2002, 2003) were followed, namely (1) to embed writing instruction into the disciplines’ curricula, and (2) to attribute at least some-responsibility for the teaching of writing to subject lecturers. These principles meant a clear departure from the existing support provision, and their application was bound to be problematic, particularly with respect to the involvement of subject lecturers. There is evidence that subject lecturers tend to be reluctant to take responsibility for student writing, partly because they feel that writing should be taught elsewhere or before students come to university, and partly because they themselves have only a tacit understanding of the conventions and requirements (e.g. North 2005; Bailey 2010). They also tend to have concerns about workload issues and the fact that teaching time might be spent on writing rather than subject content. Therefore, one objective of the writing development project was to explore different levels of lecturer involvement and to which extent they were feasible and acceptable for lecturers.

The second objective was to explore ways of integrating a focus on academic culture and practices into the teaching of academic literacy. The relevant academic debate is discussed in the next section.

3 Genre- and Practice-Focused Models of Writing Instruction

There is an ongoing discussion as to whether writing instruction should be text-led or context-led (e.g. Johns 2011). Genre-based approaches, such as EAP (e.g. Swales 1990) and the systemic functional linguistics (SFL)-oriented Sydney School (e.g. Martin 1993), base writing instruction on the analysis of texts and explicit information about the genres that students have to write, the major aim being to enable students to understand and control the discourses of their discipline. As Hyland (2008: 547) points out, genre approaches give students an explicit understanding of ‘how target texts are structured and why they are written in the ways they are’. Johns (2011) claims that text-led approaches have been more successful, and that the structure and guidance they provide are particularly appreciated by non-native speakers. She therefore recommends that explicit information about texts should be the starting point of writing instruction.

By contrast, Academic Literacies, a dominant model in the UK, strongly criticises the central role of texts, calling genre-based approaches ‘normative’ (Lillis and Scott 2007). Academic Literacies understands academic writing and reading as social practice that is influenced by factors such as power relations, the epistemologies of specific disciplines, and students’ identities (Lea and Street 1998). This social and ideological nature of writing requires, in the view of Academic Literacies proponents, a focus on practice rather than on text. As Lillis and Scott (2007: 9) assert, it is ‘the definition and articulation of what constitutes the ‘problem’ [with student writing] that is at the heart of much academic literacies research’. This focus has certainly been successful in Academic Literacies research and helped to uncover shortcomings of academic literacy support at English universities; however, its pedagogic dimension is underexplored. Academic Literacies researchers have provided only a few suggestions as to how the model could contribute to an alternative writing pedagogy. One example is Lillis’ proposal for tutor–student dialogues to make ‘language visible’ and to give students opportunities for challenging ‘dominant literacy practices’ (Lillis 2006: 34). Although desirable, this approach is not realistic for mainstream higher education where the resources for individual tutor–student discussions are not easily available. The main message that emerges from the Academic Literacies literature is that students should not be simply inducted into academic writing through the analysis of discipline-specific texts, but be supported in developing a critical awareness of disciplinary conventions to be able to challenge them (Lillis 2006; see also Lea 2004; Ivanic 1998). Similar arguments have also been voiced by Critical EAP (e.g. Benesch 2001, 2009). Others, however, see less of a need for developing students’ critical awareness, for, as Duff (2010: 171) argues, ‘language and literacy socialisation will almost inevitably involve the negotiation of power and identity’.

In any case, it is difficult to see how novice writers would be able to challenge literacy practices before they have a good understanding of texts which are the manifestations of literacy practices. This point was made by Bhatia, a member of the genre tradition who recognised that genre-based teaching might encourage prescription rather than creativity, but maintained that’ we must realise that one can be more effectively creative in communication when one is well aware of the rules and conventions of the genre’ (1993: 40). Equally, when Academic Literacies promotes the exploration of ‘alternative ways of meaning making in academia’ (Lillis and Scott 2007: 13), the obvious question arises how students can explore alternatives before they know the conventional ways.

Nevertheless, Academic Literacies offers useful insights for the development of writing instruction which may prevent the use of texts in an authoritative or prescriptive manner, and encourage the inclusion of components that foster a critical approach to literacy practices. But even when a focus on practices has been accepted as a necessary ingredient for the writing course, the question remains how this should be done. Should students be encouraged from the beginning to be critical of, or challenge conventions-bearing in mind the argument that an understanding of textual rules and conventions is the prerequisite for a critical stance? Or should they just be made aware of surrounding practices while the initial focus is on texts? The writing development project aimed to find some answers to these questions.

4 The Writing Development Project

The three instructional approaches were, as mentioned earlier, developed subsequently, and in each, an instructional model was created and evaluated in one discipline first, and then adapted to other disciplines.

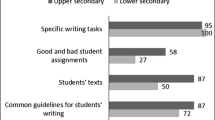

I started the project by consulting programme directors and subject lecturers from eight faculties in order to identify the support required in various disciplines, and ways in which that support could be offered. The consultation showed that there was widespread awareness of the limitations of extracurricular provision, and of the need to integrate literacy instruction into the disciplinary curriculum. At the same time, participants in the consultation had strong reservations about being involved in writing instruction and devoting classroom time to it. As a result, the first approach was conceived to keep the involvement of lecturers at the level of ‘co-operation’ (Dudley-Evans and St John 1998), requiring them to provide discipline-specific texts and information on writing requirements. These materials were incorporated into academic literacy courses which were offered online and required no further involvement of the lecturers.

4.1 Approach 1: Discipline-Specific Online Writing Instruction

The first online academic literacy course was created for undergraduate students in Management, and subsequently adapted to undergraduates and postgraduate programmes in five other disciplines. The course consists of four modules, ‘Academic Writing’, ‘Reading’, ‘Referencing’, and ‘Avoiding Plagiarism’. Course details cannot be discussed in this chapter, but further information can be found in Appendix 1 which shows the structure and content of one module, and other publications (Wingate 2008, 2011). First, I will address the question of lecturer involvement, followed by that of focus.

Management lecturers had, as already mentioned, contributed discipline-specific materials at the design stage of the course, but played no role in its delivery. In the year of implementation, 2007, the course was introduced to the first-year student cohort in a two-hour session where the relevance of the materials was explained and student questions answered. This session was not offered in subsequent years due to time and resources constraints. Instead, a Management lecturer would recommend the course in Induction Week and give students a worksheet with instructions on how to access it. Interviews with students revealed that the course was not further mentioned in the regular subject classes. This situation shows a weakness in the design of the course. It was conceptualised as an independent learning tool—although subject lecturers were supposed to be more active in promoting the course- and no links to the regular study programme were provided. This design gave subject lecturers an easy option out. The effects of their lack of involvement and the lack of integration of the course into the subject curriculum are discussed below.

The course puts equal emphasis on literacy practices and text analysis. The module ‘Avoiding Plagiarism’, for instance, offers insights into assessment policies and the concept of intellectual property in Anglophone literacy, and presents scenarios of unintentional plagiarising. The first module, ‘Academic Writing’, starts with case studies which offer opportunities to recognise social practices of writing, for instance by highlighting ‘gaps between students’ and tutors’ expectations’ and ‘issues of identity’ (Lea 2004: 744). As an example, a synopsis of Case Study 1 is shown in Table 1.

The case study is accompanied by a number of questions and associated model answers which aim to raise students’ critical awareness of mismatches between previous and expected literacy practices, the fact that lecturers’ advice on writing might not be helpful, and the potential impact of such feedback on students’ identity.

The texts presented in the online course are exemplars from expert and student writing from within the department, i.e. a journal article published by two Management lecturers, and essays by previous first-year students. In addition, students can access various forms of lecturers’ feedback comments on student writing. The associated activities ensure that texts do not have a prescriptive function; instead, they enable students to discover principles and criteria of academic writing by themselves.

The online course was evaluated by (1) monitoring students’ uptake, i.e. the number of ‘log-ins’, and (2) eliciting students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the course and its components by questionnaire and follow-up interviews. The questionnaire was administered to a total of 358 students in 2007 and 2008; 10 students from each cohort were interviewed. The uptake data shows a steep decline of first log-ins and follow-up log-ins in the year 2008 when the introductory session had been dropped. In both cohorts, only a quarter of the students who had logged in once went back to the programme again. Data from the questionnaires and interviews helped to explain this uptake pattern. Respondents regarded the course as an ‘add-on’ that seemed far less relevant than their timetabled activities. As the course was not linked to the subject teaching and hardly acknowledged by the subject lecturers, it had low priority for the students. It can be assumed that weaker students, who would have needed literacy support most, used the course least, being already stretched by the regular coursework. Therefore, the course had limited impact, and it was evident that an approach which remains detached from the everyday practices of the discipline fails to acculturate students into it.

Concerning students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the various components, an unexpected result emerged. 88 % of the 198 respondents ranked the text-focused components (in the order of student essays, lecturer comments, journal article) as most useful, while the case studies were regarded as useful by only 23 %. Other elements focusing on literacy practices received equally low ratings. This preference was explained in the interviews. The majority of interviewees commented that they had learned little from the case studies because they had come to university with an understanding of the issues presented in the case studies. This finding suggests that there may be less need for raising students’ critical awareness of practices than expected.

As the detachment of the online course from the curriculum had led to low student participation, the second approach took the opposite route of full integration of literacy instruction into the subject teaching.

4.2 Approach 2: Embedded Literacy Instruction

In 2009/10, three subject lecturers including myself conducted an intervention in which reading and writing instruction was embedded into a first-year module of an undergraduate programme in Applied Linguistics. Sixty students were enrolled in this module. Four instructional methods were embedded into the curriculum: (1) Guided reading, (2) Explicit teaching of argumentation, (3) Explicit teaching of discourse features, and (4) Formative feedback. As Appendix 2 shows, the methods were linked to (e.g. preparatory reading, formative assessment), or integrated (explicit teaching of argumentation, discourse features) into the regular subject teaching to scaffold and develop reading and writing gradually throughout the term (see also Wingate et al. 2011). One of the objectives of this approach was to disseminate the evaluation results to lecturers in other disciplines and promote embedded literacy instruction for wider use.

Through its embedded nature, this approach was successful in involving all students in the programme. It was apparent from student feedback in the evaluation that the teaching of literacy by subject tutors enhanced students’ engagement.

In the intervention, the lecturers used journal articles to demonstrate practices and norms within and beyond the discipline. For example, the references in a journal article were used to discuss how arguments are developed on the basis of evidence, and how intellectual property is acknowledged; hedges in the text were used to demonstrate the strive for caution and accuracy in academic knowledge building. Thus, this approach blended the focus on text and that on practices by using text analysis to demonstrate practices. In addition to the journal articles, samples of students’ own writing were used for analysis in group sessions.

In addition to this ‘from-text-to-practices’ method, the intervention included individual lecturer–student feedback meetings where students had the opportunity to discuss their assignments and the comments/grade they had received, as well as to challenge ‘dominant literacy practices’ (Lillis 2006: 34). In these sessions the students were encouraged to discuss their experience with, and feelings about, writing at university. Twelve of the sixty feedback sessions were recorded.

The evaluation consisted of questionnaires, interviews and the comparison of the texts written by the students earlier in the term and the end-of term assignment. In addition, the recordings of the individual feedback sessions were analysed. 89 % of the 60 students found the instructional methods useful or very useful. The individual lecturer-student feedback sessions received the highest ranking (90 %), followed by the analysis of samples of their own writing (88.1 %). The analysis of journal articles was ranked much lower (55 %). Students’ preference for working with student rather than expert texts had also emerged in the evaluation of Approach 1. This preference was explained in the interviews where some participants stated that student texts gave them a far more realistic picture of what was expected, while journal articles written by ‘real academics’ were perceived as ‘daunting’ or ‘intimidating’. The results of the text analysis are not immediately relevant to the argument in this chapter; however, they showed that the intervention had led to considerable improvements in the writing of the majority of students.

More interesting are the evaluation findings concerning the lecturer-student feedback sessions, as this method gave students the opportunity to voice unease with literacy practices. The recordings of these sessions, however, contained only two instances where students took what could be called a critical approach; both students expressed their dissatisfaction with having been taught quite different writing conventions at school. Otherwise, the recordings revealed students’ eagerness to clarify conventions and learn more about the requirements of academic writing. The interview data showed that students had ranked lecturer-student feedback sessions above the other methods because they appreciated the individual attention and advice. There was no indication that students were keen to express critique. This finding suggests that novices’ initial desire is to accommodate to the disciplinary conventions, and underlines the previous argument that novices are not ready to take a critical stance before they have gained a thorough understanding of the requirements and conventions of texts. The preliminary conclusion after the evaluation of Approach 2 was that making students aware of practices through texts is appropriate at the novice level, but expecting criticality is not.

Although the embedded approach was successful in terms of including and engaging all students in the Applied Linguistics programme, it was not successful in making an impact on other disciplines. The dissemination activities, involving academics from eight faculties, were met with reservations about the feasibility of this approach, particularly in view of the increased workload due to formative feedback and lecturer-student meetings. Only a few lecturers took up some of the instructional methods of the embedded approach.

Taking into account the findings from the first two approaches, the third approach saw a change of direction in the following aspects: (1) subject lecturers were to be involved at a level of ‘collaboration’ rather than ‘co-operation’ (Dudley-Evans and St John 1998), meaning that they would engage more than in the first approach, but not fully carry out the writing instruction like in the second approach; (2) there was no attempt to encourage students to be critical of literacy practices, and (3) only student texts were used for analysis, given the clear preference for student texts that emerged in the previous approaches.

4.3 Approach 3: Genre-Focused Writing Instruction

This approach was first developed for MA students in Applied Linguistics. The teaching and learning materials were created from a corpus compiled with texts from the two genres that students on this programme have to write, i.e. assignment (essay) and dissertation. The materials present these genres in their parts (e.g. Introduction, Literature Review) and help students to recognise and analyse the ‘moves’ (Swales 1990) occurring in these parts. Here, I give an example of the materials developed for teaching how to write a Literature Review.

For each part of a genre, six examples were chosen from the corpus. The first three examples were extracts from high achieving student assignments or dissertations, annotated with a commentary that explains typical features and strengths of this part. An example of a comment on a Literature Review would be ‘Summarises key findings from relevant literature’ with reference to the relevant text passage. Next, an extract from a high achieving assignment is offered without commentary, and students are invited to provide comments. Finally, two extracts from low achieving assignments annotated with a commentary are presented. An example of such an extract is shown in Appendix 3. This particular extract was included in the materials after an analysis of student work had revealed a tendency among students to reproduce literature rather than discussing it. As a result, students would sometimes copy entire lists of findings, hypotheses or taxonomies straight from textbooks. The example in Appendix 3 (see comments 4 and 5) shows how students are made aware of this problem.

The materials were presented and used in the teaching/learning cycle of (1) deconstruction, (2) joint construction and (3) independent construction, developed in the SFL-oriented genre-based literacy pedagogy (e.g. Martin 1999). In the deconstruction phase, students worked in groups on the extracts, discussing the features of Literature Reviews of high and low achieving assignments and summarising their findings and reflections in a note section. For the joint construction phase, one student in each group volunteered to have the Literature Review of his/her current assignment analysed and reworked by the group. In the independent construction phase, the students worked independently on their own writing and, on the basis of what they had learned in the previous phases, made changes if necessary.

The approach of genre-focused writing instruction is designed to be carried out collaboratively by subject lecturers and writing experts. As in the first approach, the subject lecturer collects the exemplar texts and provides additional information for the writing expert who prepares the materials. In addition, the subject lecturer is present during the deconstruction and joint construction phases to offer further advice and information on the textual practices highlighted in the materials. This level of involvement proved beneficial in the current example of the MA in Applied Linguistics. The fact that a subject lecturer conducted the workshops may have contributed to the high turnout of students (over 50 % per cent of all students on the programme attended although the workshops were not compulsory). The subject lecturer was repeatedly consulted on textual practices, and participated actively in the group discussions. It turned out that although no attempt to raise critical awareness was made in this approach, a few students did express a critical attitude towards certain literacy requirements. For instance, the commentary frequently highlighted the use of headings as an important structural element of academic writing. One student pointed out that he had never used headings in previous writing and felt ‘straight-jacketed’ by this requirement. The lecturer explained the value of headings for signposting the essay’s argument, but conceded that not every writer needed to use headings for signposting. The student has continued writing successful assignments without headings. This episode suggests that students do not need to be encouraged to be critical, but that the set-up (group analysis of text with lecturer available for discussion) may help to foster the expression of critique.

So far, six workshops with a total number of 82 participants have been conducted in the MA programme, in which several parts of the two genres were dealt with. The evaluation was carried out by audio recordings of the group discussions taking place in the deconstruction and joint construction phases, and by analysing the changes students made to their texts in the joint and independent construction phases. These changes were made on electronic versions of the texts and recorded through ‘Track Changes’. An analysis of the changes made in students’ own texts in phases 2 and 3 showed clear improvements. The recordings from the deconstruction phase revealed that the materials helped students to understand the relevant literacy requirements, as the following extracts from the group discussions on Literature Reviews (Appendix 3) shows:

I think the ones that did better have commented on the literature and talked about the relevance to their subject. I think you’ll probably find that the lower ones just described the literature without comment.

If you look at the bad bits, there is some sort of consistency. They say no evaluation, no headings sometimes, unsupported generalisations, no relevance, no application.

Comparing the three approaches, it seems that genre-focused writing instruction is the most effective one in several respects. First, it involves subject lecturers to a degree that is feasible in terms of workload, and effective in terms of student engagement. It is also effective in terms of resources: once the materials are developed, they can be used with many cohorts of students. Another advantage of the approach is that it precisely targets student needs by teaching exactly those genres that students have to write, and by using student texts as exemplars. The approach can easily be applied to other disciplines, and I am currently collaborating with subject lecturers from Pharmacy, History and Biomedical Science to develop genre-based materials for these disciplines.

5 Conclusion

The aim of the writing project was to give students insights and opportunities for their acculturation into academic literacy, with the objectives to examine realistic levels of subject lecturer engagement in teaching literacy on the one hand, and useful ways of raising students’ critical awareness of academic practices on the other hand. As a feasible way of involving subject lecturers has already been discussed in the previous section, my final point is concerned with acculturation, which in the view of Academic Literacies theorists not only involves students’ understanding of the literacy practices of their discipline and the wider academic context, but also their taking a critical stance towards them.

In all three approaches discussed in this chapter, students’ main interest seemed to be in learning from texts, and to accommodate to the writing conventions of their discipline. The elements in the first two approaches that aimed at raising critical awareness or offered the chance to voice a critical attitude were not particularly successful, either because the students regarded the practice-focused elements as less relevant than the textual ones (Approach 1), or because they were not ready or willing to express critique (Approach 2). By contrast, in the third approach where no specific opportunities for developing or voicing critique of practices were provided, some students voiced criticism of writing conventions that they perceived as restrictive.

I cannot draw wider conclusions from this writing project, as the three approaches were situated in different contexts, and only a few methods with which acculturation was to be achieved were used. It is for instance difficult to compare the willingness to take a critical stance towards literacy practices of novice writers in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, and it is not surprising that a critical approach was only taken by the postgraduate students in Approach 3, who, after all, are more mature and more confident having gained academic experience in their first degree. However, based on the insights I gained from the writing project, I wish to put forward a few preliminary conclusions.

First, it has become clear that the teaching of writing needs to be closely linked to the teaching of the subject. Subject lecturers play a crucial role in this teaching, as they are the ones who can acculturate students into the wider context of academic writing, for instance through the ‘from-text-to-practices’ method illustrated in Approach 2. Secondly, the findings from this project confirm the argument made earlier in this chapter that students need a firm understanding of the text and genre requirements in their discipline as a prerequisite for taking a critical approach to practices in the discipline and particularly in the wider context. Students may feel particularly uneasy or unable to critique wider issues such as university policies and related power relations when they are still trying to understand the conventions of their immediate context. What I have learned from this project is that the initial emphasis of writing instruction should not be on raising critical awareness, but on the features and requirements of texts and genres within the discipline. Text analysis led by subject tutors will relate to the wider context and eventually enable students to develop a critical perspective. From the findings of this project, this is certainly a route of acculturation into academic literacy that students want to follow.

References

Bailey, R. (2010). The role and efficacy of generic learning and study support: What is the experience and perspective of academic staff? Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 2, 1–14.

Benesch, S. (2001). Critical English for academic purposes. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Benesch, S. (2009). Theorizing and practicing English for academic purposes. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 8, 81–85.

Bhatia, V. K. (1993). Analysing genre: Language in use in professional settings. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Deane, M., & O’Neill, P. (Eds.). (2011). Writing in the disciplines. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Dudely-Evans, T., & St. John, M. J. (1998). Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A multidisciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duff, P. (2010). Language socialisation into academic discourse communities. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 169–192.

Hyland, K. (2008). Genre and academic writing in the disciplines. Language Teaching, 41(4), 543–562.

Johns, A. M. (2011). The future of genre in L2 writing: Fundamental, but contested instructional decisions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20, 56–68.

Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ivanic, R., & Lea, M. (2006). New contexts, new challenges: The teaching of writing in UK higher education. In L. Ganobcsik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education (pp. 6–15). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lea, M. (2004). Academic literacies: A pedagogy for course design. Studies in Higher Education, 29(6), 739–756.

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172.

Lillis, T. M. (2003). Student writing as ‘Academic Literacies’: Drawing on Bakhtin to move from critique to design. Language and Education, 17(3), 192–207.

Lillis, T. M. (2006). Moving towards an ‘Academic Literacies’ pedagogy: Dialogues of participation. In L. Ganobcsik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education (pp. 30–45). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lillis, T. M., & Scott, M. (2007). Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 5–32.

Martin, J. R. (1993). A contextual theory of language. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), The powers of literacy. A genre approach to teaching writing. London: The Falmer Press.

Martin, J. R. (1999). Mentoring semogenesis: ‘Genre-based’ literacy pedagogy. In F. Christie (Ed.), Pedagogy and the shaping of consciousness: Linguistic and social processes (pp. 123–155). London: Cassell.

Monroe, J. (Ed.). (2002). Writing and revising the disciplines. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Monroe, J. (2003). Writing and the disciplines. Peer Review, 6(1), 4–7.

North, S. (2005). Different values, different skills? A comparison of essay writing by students from Arts and Science backgrounds. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 517–533.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wingate, U. (2006). Doing away with study skills. Teaching in Higher Education 11(4), 457–465.

Wingate, U. (2008). Enhancing students’ transition to university through online pre-induction courses. In R. Donnelly & F. McSweeney (Eds.), Applied eLearning and eTeaching in higher education (pp. 178–200). London: Information Science Reference.

Wingate, U. (2011). A comparison of ‘additional’ and ‘embedded’ approaches to teaching writing in the disciplines. In M. Deane & P. O’Neill (Eds.), Writing in the disciplines (pp. 65–87). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Wingate, U., Andon, N., & Cogo, A. (2011). Embedding academic writing instruction into subject teaching: A case study. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(1), 69–81.

Wingate, U., & Tribble, C. (2012).The best of both worlds? Towards an English for academic purposes/academic literacies writing pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education, 37(4), 481–495.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1: Outline of the Online Module ‘Academic Writing’

Appendix 2: The Five Methods of Embedded Writing Instruction

Method | Details | Timing |

|---|---|---|

1. Guided reading | Students read journal articles; activities for learning to take notes, write summaries | Reading article in preparation for week 1/week 4 |

Online submission of notes and summaries | ||

2. Explicit teaching of argumentation | Introduction of Toulmin model of argumentation | 30-min seminar in induction week |

Students analyse arguments in journal articles | Week 3/20 min of classroom session | |

Students analyse samples of their own writing | Week 11/20 min of classroom session | |

3. Explicit teaching of discourse features | Lecturer pointing out discourse features in journal articles | Week 3; week 4/20 min of classroom session |

4. Formative feedback | Individual feedback on writing | Feedback on online submissions: week 1 |

Feedback (1–3) to be used for final assignment due in week 12 | Feedback on exploratory essay provided in week 7 | |

Feedback on essay in parallel module, provided in week 10 |

Appendix 3: Example from Genre-Focused Writing Materials

Extract from Literature Review in a low scoring assignment

-

Review the analyses for the discussion sections in low scoring assignments given below.

-

Summarise the ways in which these discussion sections differ from the four previous sections in high achieving assignments.

Example A. [1] | [1] This is a new section concerned with the classification of learning strategies. There is no heading to indicate the focus of this section |

In terms of the taxonomies of language learning strategies, there are such a variety of learning strategies that numerous taxonomies have arisen (Oxford 1990; O’Malley and Chamot 1990) [2]. Oxford (1990: 38, 136) developed Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) which uses factor analysis to group strategies into six categories: [3] | |

Memory-related strategies: learners link one L2 item or concept with another without necessarily involving deep understanding, e.g. key words, acronyms, sound similarities, imagery, rhyming, and reviewing in a structured way | [2] It is unclear how many taxonomies exist, and whether these authors commented on the variety, or whether they developed taxonomies |

Cognitive strategies: learners manipulate language material in direct ways, e.g. reasoning, repetition, translation, analysing, note-taking, summarising and practicing | |

Compensation strategies: learners make up for limited or missing knowledge such as circumlocution, guessing meanings from the context and using synonyms or gestures to convey meaning | [3] If there are so many taxonomies, it needs to be explained why the SILL is presented in detail |

Metacognitive strategies: learners evaluate progress, plan for language tasks, consciously search for practising opportunities, pay attention to errors and monitor language production and comprehension | |

Affective strategies: learners manage their own emotions, moods and motivation | |

Social strategies: learners use social-mediating activities and interaction with others, such as cooperation, questions for clarification, conversations with native speakers, and exploring cultural and social norms [4] | [4] The list of six categories is taken directly from Oxford (1990). This list reflects a report rather than an analysis in which different taxonomies would be summarised, compared, and evaluated |

An alternative taxonomy is developed by O’Malley and Chamot (1990: 46) who classify language learning strategies into the following categories: [5] | [5] Another list follows without comparison, evaluation and application to the context of the essay |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wingate, U. (2014). Approaches to Acculturating Novice Writers into Academic Literacy. In: Łyda, A., Warchał, K. (eds) Occupying Niches: Interculturality, Cross-culturality and Aculturality in Academic Research. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02526-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02526-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-02525-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-02526-1

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)