Abstract

In recent years the study of learning and teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) has ceased to be based solely on quantitative or qualitative methods. Instead, the third orientation, mixed methods research, has gained in popularity. This article reports on a review of a sample of EFL mixed methods articles. The findings of the review show how mixed methods are conceptualized and justified in EFL classroom research as well as what ways and levels of integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches occur most frequently. Some suggestions for further research are also offered.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

In recent years, mixed methods research has become increasingly popular in many areas of social sciences, including education. The definitions of this type of research vary in the depth and breadth of the description of the purposes and processes involved. One of the more general definitions says that mixed methods research is “the class of research where the researcher mixes or combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques, methods, approaches, concepts or language into a single study” (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004, p. 17). The underlying principle of mixed methods research, as evident in the majority of definitions, is first, the idea of combining or mixing or integrating methods, and second, the presence or co-existence of two paradigmatically distinct research orientations; qualitative and quantitative. Mixed methods research follows the usual research procedures supplemented with some additional stages, such as decision-making and justification of method mixing, choosing the appropriate way of mixing methods and, finally, interpretation of the combined results (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004; Collins et al. 2006).

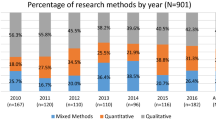

Mixed methods research is by no means new to the field of EFL classroom research. The encouragement to combine qualitative and quantitative research methods in L2 research came in the 1980s from Chaudron (1988) and later from Allwright and Bailey (1991). In a brief introduction to the chapter on mixed methods research, Dörnyei (2007) writes about the increasing use of this research orientation in applied linguistics; however, he rightly observes that “most studies in which some sort of method mixing has taken place have not actually foregrounded the mixed method approach and hardly any published papers have treated mixed methodology in a principled way” (Dörnyei 2007, p. 44). Furthermore, he also quotes Magnan’s (2006) editorial, in which it has been stated that only 6.8 % of articles published in The Modern Language Journal between 1995 and 2005 reported the combining of qualitative and quantitative research methods. For comparison, a review of recent issues of System and TESOL Quarterly (2010- autumn 2011) reveals that out of 70 research articles as many as 22 % report a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods, but, interestingly, only 2 articles (2.9 %) make an explicit reference to the mixed methods tradition. This may mean that researchers are no longer exclusively devoted to only one of the research traditions, having to choose between a qualitative and quantitative orientation, and they feel free to combine these two in one study for a variety of purposes, such as gaining deeper insight into the issue, taking a broader perspective or complementing data. What can be observed, however, is that most research articles reporting the use of the combination of these two research orientations do not make any explicit references to mixed methods research. There is also no comprehensive review of the use of mixed methods for studying teaching and learning EFL. A notable exception is the aforementioned Dörnyei’s (2007) book, which is the first to discuss mixed methods in applied linguistics. However, this discussion draws mainly on general literature on research methodology with little reference to EFL studies.

In spite of the interest in theoretical debates about mixed methods and the encouragement to carry out research within this third methodological orientation, at present, we still do not know much about the actual practice of mixed methods in the field of EFL teaching and learning, or about the conceptualization of mixed methods, as well as about the reasons for and the ways of combining these two different research approaches in one study. The need for such an examination of practice has also been observed by Bryman (2006, p. 99) as he comments that “we have relatively little understanding of the prevalence of different combinations” and further makes a strong point supporting his call for the study of the actual mixing of methods (Bryman 2006, p. 111):

(…) there is considerable value in examining both the rationales that are given for combining quantitative and qualitative research and the ways in which they are combined in practice. Such a distinction implies that methodological writings concerned with the grounds for combining the two approaches need to recognize that there may be a disjuncture between the two when concrete examples are examined.

The aim of this article, therefore, is to examine examples of mixed methods studies in the area of teaching and learning EFL with a view to describing the actual practice of combining quantitative and qualitative approaches in studies conducted in this particular field. To this end, the following aspects of mixed methods studies will be considered:

-

How is mixed methods research conceptualized in EFL studies?

-

What is the rationale for the use of mixed methods in EFL studies?

-

What types of mixed methods research designs predominate in EFL studies, including timing and weighting and data collection methods?

2 Methodology: Selection and Review of the Articles

Although the number of studies mixing quantitative and qualitative methods is increasing, only some of them explicitly adhere to the mixed methods orientation. In this preliminary review only those studies have been taken into consideration, assuming that combining qualitative and quantitative data collection methods without foregrounding of mixed methods research may indicate that the author does not identify his/her research with mixed methods. The other limitation applied to the selection of articles was the field of study, namely teaching and learning EFL. In order to identify articles for the analysis, the Academic Search Premier full text database was searched using ‘mixed methods’ and ‘efl’ or ‘mixed methods’ and ‘English’ as key words, but this yielded a very modest result of only 3 articles, and the replacement of ‘mixed methods’ with the singular ‘mixed method’ added one more result. Subsequent review of academic journals yielded several more results. Hence, 16 journal articles altogether were identified. However, after an initial reading, one of them was excluded from the analysis since it provided an account of only one part of a study where only a single method was applied. The reviewed articles come from the following journals: System (4), Assessing Writing, Teaching and Teacher Education (2), Journal of English for Academic Purposes, World Englishes, Language Teaching Research, Computer Assisted Language Learning, Educational Technology and Society, International Journal of Language Studies, Language Testing and TESOL Quarterly. The articles were published between 2007 and 2011.

The articles were read first to identify in which parts of the article the term ‘mixed methods’ is used, as this might indicate the importance this particular research method had for the author/s and for the study. The position of this information might also suggest how important the author/s thought it was for the reader. During the second reading, the focus was on the conceptualizations of mixed methods and the justifications for its use which, later on, were compared to the definitions and justifications discussed in general research methodology studies. Finally, the research account was analyzed in order to identify the research designs. The data collected from this content analysis revealed certain patterns and tendencies in the actual practice of using mixed methods.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Situating References to Mixed Methods within an Article

The analysis revealed only three articles (Barkaoui 2007; Chen 2008; Kim 2009) in which mixed methods are referred to in the title. In two cases, the reference to mixed methods constitutes the second part of a compound title, in one case it is placed at the beginning of the title; thus the titles immediately provide relevant information about the research methodology adopted by the authors. In this way, the audience are immediately provided with information about the methodological approach applied in the study. In seven cases, the information about the methodology is announced in the abstracts, which means that the reader is informed about the methodology used fairly early on, which may suggest the importance of combining methods and a concern for the reader to be introduced to the methodological orientation of the reported research from the outset. In two other cases, this information appears in the introduction to the article. Strangely enough, in two of the articles, the mention of mixed methods methodology is placed at the end of the literature review section. Most naturally, the information about methodology is included in the ‘methods’ sections, but in the case of the 15 reviewed articles this happens only in nine instances. In four cases, ‘mixed methods’ appears only in the abstracts, with no further references in the other sections of the article. These numbers show only where in the article the term ‘mixed methods’ appears; however, references to combining methods are made more frequently throughout the articles.

3.2 Defining Mixed Methods Research

Johnson et al. (2007, p. 129), having analyzed definitions of mixed methods formulated by 18 scholars, offered a comprehensive view of mixed methods research:

Mixed methods research is an intellectual and practical synthesis based on qualitative and quantitative research; it is the third methodological or research paradigm (along with qualitative and quantitative research). It recognizes the importance of traditional quantitative and qualitative research but also offers a powerful third paradigm choice that often will provide the most informative, complete, balanced, and useful research results.

In this definition, the authors explicitly make references to both the theoretical and practical aspects of mixed methods which, borrowing from the quantitative and qualitative traditions, constitute a distinct, new research paradigm. There has been some argument about the compatibility of worldviews underlying qualitative and quantitative studies, regarding the feasibility of mixing these worldviews in a single study. One of the solutions, discussed by Gelo et al. (2008, p. 278), is a dialectical stance which makes it possible to view all paradigms as equally important in guiding the research, incorporating “multiple sets of philosophical assumptions toward better understanding” and “a broader set of beliefs and assumptions, and (…) more diverse sets of methods”. The definition offered by Johnson et al. (2007) alludes not only to a worldview, but also points out the potential benefits of this third paradigm. Further, they offer a more detailed view of mixed methods as being rooted in a philosophy of pragmatism, following the logic of mixed methods research, relying on qualitative and quantitative viewpoints, data collection, analysis and interpretation, combined to address research questions, taking also into consideration the context of the research. (Johnson et al. 2007, p. 129).

In a definition suggested by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2009, p. 267), the emphasis is placed on the subsequent steps in the research procedure: “(…) mixed methods research represents research that involves collecting, analyzing, and interpreting quantitative and qualitative data in a single study or in a series of studies that investigate the same underlying phenomenon”. Dörnyei (2007, p. 44), while discussing mixed methods research in the field of applied linguistics, defines this research orientation as “some sort of a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods within a single research project”. This definition is very general and lacks precision, since mixed methods research is not a simple addition of quantitative and qualitative research, but is ruled by its own logic. Creswell and Plano Clark (2010), dissatisfied with the definitions of mixed methods scattered across a variety of methodology textbooks and articles, have come up with a set of core characteristics of mixed methods instead of a single definition. From their point of view, mixed methods research:

-

collects and analyses persuasively and rigorously both qualitative and quantitative data (based on research questions);

-

mixes (or integrates, or links) the two forms of data concurrently by combining them (or merging them), sequentially by having one built on the other, or embedding one within the other;

-

gives priority to one or to both forms of data (in terms of what the research emphasizes);

-

uses these procedures in a single study or in multiple phases of the program of a study;

-

frames these procedures within philosophical worldviews and theoretical perspectives; and

-

combines the procedures into specific research designs that direct the plan for conducting the study (Creswell and Plano Clark 2010, p. 5).

This set of characteristics, typical of mixed methods, not only pictures this research approach in more detail but it can also guide the mixed methods researcher in planning and executing such research.

In the examined EFL research articles, the majority of authors do not express their paradigmatic stance and they do not write explicitly how they understand mixed methods research. In two of the articles, it has been articulated that a mixed method approach involves combining quantitative and qualitative research methods into a single study:

The methodology applied in this research is mixed-methods, including both quantitative and qualitative methods, which takes advantage of the strength of one of the methods as a means of compensating for the weaknesses inherent in the other method (Chen 2008, p. 1018).

A mixed methods approach, known as the ‘third methodological movement’ (…) incorporates quantitative and qualitative research methods and techniques into a single study and has the potential to reduce the biases inherent in one method while enhancing the validity of inquiry (…) (Kim 2009, p. 191).

Intramethod mixing, in which a single method concurrently or sequentially incorporates quantitative and qualitative components (…) (Kim 2009, p. 192)

Chiang (2008), in his definition of mixed methods, mentions only one possible combination in which one approach is used to explain the results gained by another approach:

In a mixed method approach, the qualitative analysis describes and explains the rationales for the quantitative results (…) (Chiang 2008, p. 1774).

The first theme that is present in these three definitions is the combining of qualitative and quantitative methods in a single study, which is in accordance with the definitions mentioned earlier. Chen and Kim develop their definitions by incorporating the fundamental principle of mixed methods, which says that the strengths of one method may overcome the weaknesses of another if both are applied in a single study (Johnson and Turner 2003; Gelo et al. 2008). Kim also indicates that this compensatory potential serves triangulation purposes, by enhancing the validity of the research. Further in the article, Kim refers to intramethod mixing, closely following Johnson and Turner’s (2003) definition, contrasted with intermethod mixing, which involves multiple methods reflecting quantitative and qualitative approaches. Chiang’s definition is much narrower, although his study includes a variety of data collection methods employed at different phases of research, both sequentially and concurrently.

The analysis of how researchers in the EFL area articulate their understanding of mixed methods, especially when compared with definitions from the research methodology field, and the infrequency of any attempts to define mixed methods, may suggest that the authors are not preoccupied with worldviews, but that the research process is driven mainly by research goals and questions that may require data of different type.

3.3 Justifying the Use of Mixed Methods Research

Quantitative and qualitative methods are brought together in a single study for a variety of reasons which have been widely discussed due to the importance of having sound justification for method mixing (Creswell 1999; Johnson and Turner 2003; Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004; Gorard and Tylor 2004; Dörnyei 2007; Schulenberg 2007; Gelo et al. 2008). Greene et al.’s (1989) classification of purposes for mixing methods was the first comprehensive attempt at identifying such purposes, which resulted in 5 broad categories: triangulation, complementarity, expansion, development and initiation. In a more recent work, Bryman (2006) provides a detailed scheme of 16 reasons for combining methods, based on an analysis of a fairly large amount of 232 social science articles. In the conclusion to his study, he appeals to the authors of mixed research articles for greater explicitness about the purposes of mixing methods in a study.

In the 15 articles reviewed, however, only a few authors provide such an explicit discussion of their reasons for combining methods. For example, Chang (2010) writes that quantitative data are not sufficient to explain how the variables in the research are related. The implementation of qualitative methods allowed the elaboration and illustration of the results from one method with the data from another, which yielded a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under investigation. Similarly Kim (2009), by mixing methods, attempted to enhance the understanding of markers’ behaviour, not only by investigating the scores assigned by teachers, but also by examining how they assessed students’ oral English performance. Corcoran (2011) sought to complement quantitative findings with qualitative ones to achieve elaboration, enhancement, illustration and clarification. Most authors used mixed methods assuming that this approach was appropriate to investigate a complex phenomenon and that data collected using paradigmatically different methods can provide a richer, clearer, deeper or broader picture. In the remaining part of this section, the rationales for mixing methods in each study will be discussed in reference to Greene et al.’s (1989) classification in order to shed more light on the reasons which guided the researchers in choosing mixed methods as the basis for their inquiries.

The analysis of the sample articles reveals that the main purpose of mixing the methods was complementarity, which was “used to measure overlapping but also different facets of a phenomenon, yielding an enriched, elaborated understanding of that phenomenon” (Greene et al. 1989, p. 258). The following examples illustrate this purpose well:

(…) quantitative data was necessary for the general baseline information on each group’s level of autonomy. Including qualitative instruments was vital to provide a clearer, more complete picture of the research findings” (Sanprasert 2010, p. 13).

In focus group interviews, students and teachers were asked to comment on salient features which emerged from the questionnaires in order to add explanations, caveats, personal views, and anecdotal evidence on the statistical data. This additional information can thus “enrich the bare bones of statistical results” (…) and provide valuable insider viewpoint for the interpretation of the questionnaires (Grau 2009, p. 165).

In the discussion of the results, both data from the quantitative and qualitative part of the study will be used in order to give a more comprehensive view (Grau 2009, p. 166).

Data collected through semi-structured teacher interviews and focus groups provide a more in-depth understanding of NEST superiority rejection (…) (Corcoran 2011, p. 149).

Qualitative data allow us to gain a better understanding of this apparent demand for teachers with experience of living abroad (Corcoran 2011, p. 151).

Qualitative data give a more nuanced picture of the contrasting and, at times, the seemingly contradictory nature of teacher beliefs on the importance of native-like proficiency (Corcoran 2011, p. 153).

More examples can be found in Kim (2009, p. 210), Corcoran (2011, p.147), Chang (2007, p. 328), and Chiang (2008, p. 1247). Similarly to the results of this analysis, complementarity was the most frequent justification for method mixing in the review of social science research articles by Bryman (2006).

The second important purpose was development, in the sense that the results from one method help develop or inform the other method (Greene et al. 1989, p. 259). For example, in Chang’s (2007) study, the interview sample was chosen on the basis of earlier survey results; and vice versa, in Mazdayasna and Tahririan’s (2008) study, qualitative interview data served as input for designing a qualitative questionnaire.

Barkanoui’s (2007) study is an example of combining methods for purposes of expansion, which “seeks to extend the breadth and range of inquiry by using different methods for different inquiry components” (Greene et al. 1989, p. 259). In his study, Barkanoui employed quantitative methods to study the product (teachers’ marking of essays) and a qualitative method to study the process of marking and its perception. By comparison, expansion was the second most frequent rationale used in Bryman’s (2006) study.

For some authors, the rationale for mixing methods was the need for triangulation. However, this concept has been occasionally misunderstood, and used when the author aimed at complementarity and not genuine triangulation. Triangulation originally meant that the results of different measurements were compiled in order to overcome weaknesses and biases in each of them so that they better support the understanding of a phenomenon. Triangulation “(…) requires that the two or more methods be intentionally used to assess the same conceptual phenomenon, be therefore implemented simultaneously, and, to preserve their counteracting biases, also be implemented independently” (Greene et al. 1989, p. 256). Although triangulation has been mentioned by a few authors, in actual practice, what they really meant was complementarity, where different methods addressed different questions, albeit concerning the same phenomena (e.g. Chang 2010). The following examples illustrate how the authors perceived the purposes of triangulation:

Triangulating quantitative survey data with a more detailed illustration from language learners through interviews allows the researcher to gather qualitative data to “explain or build upon initial quantitative results (…) (Chang 2010, p.136).

Three quantitative and qualitative methods (…) were analyzed to provide a triangulated interpretation (…) (Miyazoe and Anderson 2010, p. 190).

Triangulated data from teacher and student survey-questionnaires, teacher and administrator interviews, and teacher focus groups point to a rejection by NNESTs of NESTs as superior language teachers for a variety of stated reasons (…) (Corcoran 2011, p. 156)

(…) a way to validate data through triangulation (Grau 2009, p. 165).

Initiation, the last purpose in Greene et al.’s classification, “seeks the discovery of paradox and contradiction, new perspectives of frameworks, the recasting of questions or results from one method with questions or results from the other method” (1989, p. 259). In this sample, none of the authors made a reference to this purpose, which is a very similar result to Bryman’s (2006) findings.

Amuzie and Winke’s (2009, p. 369) justification does not fit any of the categories, since it talks about addressing the complexity of the problem: “We believe that a mixed method approach is appropriate for investigating a complex phenomenon such as changes in beliefs”. The analysis of the articles also shows that some authors mention more than one rationale for method mixing (Amuzie and Winke 2009, p. 370; Kim 2009, p. 191; Corcoran 2011, p. 147) and articles whose authors do not justify the combining of methods at all (e.g. Ranalli 2008; Fang 2010). However, not providing a rationale for mixing methods goes against the key principle of mixed methods, which says that methods should be combined only if there is an important reason for it (Creswell and Plano Clark 2010, p. 61).

3.4 Mixed Methods Designs

Research design is a set of “procedures for collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and reporting data in research studies” (Creswell and Plano Clark 2010, p. 53). Mixed methods research follows the usual research procedures. However, these procedures are expanded due to the fact that the mixed methods researcher needs to take decisions concerning the aim and justification of method mixing, to choose the means of method mixing and, finally, to interpret the combined results (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004; Collins et al. 2006). Therefore, mixed methods designs are usually more complex than purely quantitative or qualitative designs. Mixed methods designs are usually identified on the basis of three fundamental factors which can be differently combined. The first factor is the degree of mixing, from partial to full. Fully mixed designs involve using both qualitative and quantitative research within one or more of the following or across the following four components in a single study: the research objective, type of data and operations, type of analysis and type of inference (Leech and Onwuegbuzie 2009, p. 267). In a partially mixed study, the quantitative and qualitative research is conducted separately and is mixed at the interpretation stage. The next factor refers to the time at which the methods are applied, either concurrent or sequential (Leech and Onwuegbuzie 2009). Concurrent designs include studies where the stages of the research which address related aspects of the same research question occur simultaneously, although for practical reasons a small time lapse is possible. Sequential designs refer to studies where the quantitative and qualitative stages occur in chronological order (Teddlie and Tashakkori 2009, p. 143). The final factor is the weight, or dominance, of one method over the other, which means that the quantitative and qualitative methods may have equal weight, or one may dominate the other. The typology of mixed methods designs developed by Creswell and Plano Clark (2010, pp. 73–76) includes additional factors, such as paradigm foundation, level of interaction, the phase where mixing happens, mixing strategies, and design purpose. Taking all these factors together, they propose six basic design types with variants: convergent, explanatory, exploratory, embedded, transformative and multiphase designs.

The mixed methods designs of the examined studies were analyzed in reference to the above-mentioned typology. In the examined sample, the explanatory design predominates. In this design quantitative data are collected first and the subsequent qualitative data are meant to explain, or shed more light on the quantitative results; the two strands, quantitative and qualitative, remain interactive and are implemented sequentially. For example, in Chang’s (2007) study, first quantitative data on individual learners’ levels of autonomy and learner group characteristics were collected, and then interviewees were selected on the basis of their questionnaire responses to provide a more complete understanding of the relationship of group processes and learner autonomy being studied. In another study (Amuzie and Winke 2009), the effect of studying abroad on learners’ language learning beliefs was explored, first on the basis of belief questionnaires administered prior to and during the period spent studying abroad, and then more insight into the problem was provided by qualitative interviews. Other studies which employ explanatory designs are Grau (2009), Fang (2010), Kim (2009), and Chang (2010).

An exploratory design, which is also interactive and sequential, involves first collecting qualitative data and then searching for quantitative data in order to gain additional information. The only example of this design is Mazdayasna and Tahririan’s (2008) study of the needs of Iranian ESP students. The study began with interviews whose results provided the input for a structured questionnaire with the aim of getting quantitative information about the issues that emerged during them.

Chiang’s (2008) research is an example of a multiphase design, which is described as interactive, with equal emphasis on each approach, and with multiphase combination of the approaches. In this design, the collection of quantitative and qualitative data is not linear, but happens at different stages of the research, both sequentially, simultaneously and concurrently. The focus of Chiang’s research was the effect of fieldwork experience on foreign language teachers’ development. To this end, a self-report survey was administered at the beginning of the study and an EFL Teacher Efficacy Scale (TES) was administered before and after the course. The survey looked for both qualitative and quantitative data while the TES for quantitative data only. During the course, semi-structured group interviews were held and at the end of the course the students were supposed to write reflective essays. Apart from this, throughout the course the students kept reflective logs which provided qualitative data. This multiphase combination served the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the teacher training course.

A convergent design uses a combination of methods which are independent, with equal emphasis on each research strand, and implemented concurrently. This design was employed in the study of EFL teachers’ Internet use during language instruction (Chen 2008). A survey was used to obtain quantitative data and interviews were held concurrently with 22 teachers. In this study, all the conditions for convergent design were met: implementing qualitative and quantitative strands during the same phase of the research, equal weight of the two strands, independent analysis, and merging of the results at the interpretation phase (Creswell and Plano Clark 2010, pp. 70–71).

Embedded design is interactive, either the qualitative or quantitative method comes first, and it can be either sequential or concurrent. This design was followed in Sanprasert’s study (2010), in which experimental quantitative research was supplemented with additional qualitative data from the diaries kept throughout the experiment (application of a course management system to enhance autonomy).

Finally, transformative design is interactive, the emphasis on quantitative and qualitative strand is equal, the strands may be implemented either concurrently or sequentially. No examples of transformative design were found in the examined sample of articles.

Each of the aforementioned design types is defined, among other features, by the timing of the research procedures. In the studied sample, sequential implementation of data collection is much more frequent than concurrent, with 11 instances. In two cases (Chiang 2008; Sanprasat 2010), both sequential and concurrent data collection took place. The second key characteristic of the designs is the weight or, in other words, dominance of one method over the other. This characteristic, however, was not given enough attention. The weight of each research strand was generally not stated explicitly in the articles, except for two of them. In Kim’s (2009) study, dealing with the ways in which native and non-native teachers of English assess students’ oral performance, the same weight was given to both components, whereas in Corcoran’s (2011) study qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and focus groups was weighted more heavily than the quantitative data from questionnaires. In other studies, the weight is not mentioned, but it can be observed that the weight of both strands in the majority of cases remains equal, and in a few studies quantitative methods dominate the qualitative ones.

Some designs, however, are somewhat problematic and not easy to categorize. There are studies in which qualitative data are quantized, or in which interviews or questionnaires yield both quantitative or qualitative data. There are also studies in which only one of several data collection tools looks for both quantitative and qualitative data (e.g. Mazdayasna and Tahririan 2008; Ranalli 2008; Gao et al. 2010). This last case, where both types of data come from one data collection tool, may be especially problematic, considering the view of some methodologists, who do not treat it as an example of true method integration (Bryman 2006, p. 103).

The last issue addressed in this analysis is the type of data collection method used. In mixed methods research, data collection involves the mixing of quantitative and qualitative approaches. The mixing can take place at an intermethod or intramethod level. Intramethod mixing (data triangulation) involves concurrent or sequential mixing of qualitative and quantitative components within a single method, whereas intermethod mixing (method triangulation) employs concurrent or sequential mixing of two or more methods (Johnson and Turner 2003). In this sample, the methods used to collect quantitative data were questionnaires, pre- and post-tests, observation, ratings, think-aloud protocols and the Teacher Efficacy Scale. As many as 10 studies made use of a survey. In four cases, the method contained both quantitative and qualitative components, as in the surveys in the studies of Chiang (2008), Ranalli (2008), and Gao et al. (2010), and in the ratings accompanied by qualitative comments in Kim’s (2009) study. The qualitative data collection involved interviews (12 studies), both individual and focus group. Additionally, diaries and logs, written assignments and reflective essays were employed. The data collection methods used most frequently were questionnaires (for quantitative data) and interviews (for qualitative data), which is again in accordance with Bryman’s (2006) findings.

4 Summing Up and Conclusions

In this chapter we have looked at three crucial aspects of mixed methods implemented in the context of EFL studies, namely, the conceptualization of mixed methods, the rationale for the use of mixed methods, and research designs. The analysis of this sample of mixed methods research articles reveals infrequency of the actual use of this type of research in EFL studies, rare attempts to define what mixed methods mean for an EFL researcher, and certain tendencies in justifying and designing these studies. The researchers’ decisions to apply mixed methods is driven by their research questions and the need for multiple data, not by their worldviews, which is quite a common situation in mixed methods research. The authors usually provide a rationale for mixing qualitative and quantitative research methods; the most frequent reason for combining methods is the complementarity of data needed to gain a deepened understanding of the investigated phenomena. The research designs implemented to study teaching and learning of EFL usually follow a relatively simple explanatory design, although other design types are also occasionally used. Data collection varies, depending on the research problem. However, most studies employ questionnaires and interviews alongside other tools. The mixing of methods is mainly partial and occurs at the data collection and interpretation stages, whereas the analysis of data is conducted separately for quantitative and qualitative data.

This preliminary analysis of mixed methods studies in the EFL field may serve as a starting point for further examination. First of all, there is a need to identify a substantially larger, more representative sample of mixed methods EFL studies and to refine their purposes and designs. It is also important to evaluate the relationship between mixed methods research and the purposes of EFL studies, to identify patterns of combining, and to evaluate the applicability of the results of mixed methods studies. There is also a need to confront researchers’ declarations regarding rationale and design with their actual performance. Further analysis of mixed methods in EFL studies should also include research accounts which do not refer to the term ‘mixed methods’ but still use both qualitative and quantitative methods. Will they turn out to belong to mixed methods or constitute a different type of research? Additionally, an examination of mixed methods research accounts in journal articles could provide useful information about how they relate to solely quantitative or qualitative research descriptions and what the challenges of this (new) genre are. In 2009, Leech and Onwuegbuzie wrote that the mixed methods paradigm was still in its adolescence. This preliminary analysis and suggestions for further research support this view, as far as we refer to research in the field of EFL.

References

Allwright, R. L. and K. M. Bailey. 1991. Focus on the language classroom: An introduction to classroom research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amuzie, G. L. and P. Winke. 2009. Changes in language learning beliefs as a result of study abroad. System 37: 366–370.

Barkaoui, K. 2007. Rating scale impact on EFL essay marking: A mixed-method study. Assessing Writing 12: 86–107.

Bryman, A. 2006. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research 6: 97–113.

Chang, L. Y. 2007. The influences of group processes on learners’ autonomous beliefs and behaviors. System 35: 322–337.

Chang, L. Y. 2010. Group processes and EFL learners’ motivation: A study of group dynamics in EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly 44: 129–154.

Chaudron, C. 1988. Second language classroom: Research on teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Y. L. 2008. A mixed-method study of EFL teachers’ Internet use in language instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 1015–1028.

Chiang, M. H. 2008. Effects of fieldwork experience on empowering prospective foreign language teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 1270–1287.

Collins, K. M. T., A. J. Onwuegbuzie and I. L. Sutton. 2006. A model incorporating the rationale and purpose for conducting mixed-methods research in special education and beyond. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal 4: 67–100.

Corcoran, J. 2011. Power relations in Brazilian English language teaching. International Journal of Language Studies 5: 141–166.

Creswell, J. W. 1999. Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In Handbook of Educational Policy, ed. G. J. Cizek, 455–472. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Creswell, J. W. and V. L. Plano Clark. 2010. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Dörnyei, Z. 2007. Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fang, Y. 2010. Perceptions of the computer-assisted writing program among EFL college learners. Educational Technology & Society 13: 246–256.

Gao, X., G. Barkhuizen and A. Chow. 2010. ‘Nowadays, teachers are relatively obedient’: Understanding primary school English teachers’ conceptions of and drives for research in China. Language Teaching Research 15: 61–81.

Gelo, O., D. Braakman and G. Benetka. 2008. Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate. Integrative Psychological Behavior 42: 266–290.

Gorard, S. and Ch. Taylor. 2004. Combining methods in educational research. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.

Grau, M. 2009. Worlds apart? English in German youth cultures and in educational settings. World Englishes 28: 160–174.

Greene, J. C., V. J. Caracelli and W. F. Graham. 1989. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11: 255–274.

Johnson, R. B. and A. J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Research 33: 14–26.

Johnson, R. B., A. J. Onwuegbuzie and L. A. Turner. 2007. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1: 112–133.

Johnson, R. B. and L. A. Turner. 2003. Data collection strategies in mixed method research. In Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research, eds. A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie, 297–319. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Kim, Y-H. 2009. An investigation into native and non-native teachers’ judgements of oral English performance: A mixed methods approach. Language Testing 26: 187–217.

Leech, N. L. and A. J. Onwuegbuzie. 2009. A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity International Journal of Methodology 43: 265–275.

Magnan, S. 2006. From the editor: The MLJ turns 90 in a digital age. Modern Language Journal 90: 1–5.

Mazdayasna, G. and T. H. Tahririan. 2008. Developing a profile of the ESP needs of Iranian students: The case of students of nursing and midwifery. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7: 277–289.

Miyazoe, T. and T. Anderson. 2010. Learning outcomes and students’ perceptions of online writing: Simultaneous implementation of a forum, blog, and wiki in an EFL blended learning setting. System 38: 185–199.

Ranalli, J. 2008. Learning English with The Sims: Exploiting authentic computer simulation games for L2 learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning 21: 441–455.

Sanprasert, N. 2010. The application of a course management system to enhance autonomy in learning English as a foreign language. System 38: 109–123.

Schulenberg, J. L. 2007. Analysing police decision-making: Assessing the application of a mixed-method/mixed-model research design. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10: 99–119.

Teddlie, C. and A. Tashakkori. 2009. Foundations of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wiśniewska, D. (2014). The Why and How of Using Mixed Methods in Research on EFL Teaching and Learning. In: Pawlak, M., Bielak, J., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (eds) Classroom-oriented Research. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Springer, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00188-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00188-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-00187-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-00188-3

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)