Abstract

A modification of the well-known laminar composite structure with 2–2 connectivity leads to changes of the effective physical properties and their dependences on the composite content and microgeometric characteristics. The present chapter reports new results on novel three-component 2–1–2 composites with a high piezoelectric sensitivity and large hydrostatic parameters. In the 2–1–2 composite, there are parallel-connected layers of two types. The first type represents a ferroelectric domain-engineered [0 0 1]-poled lead-free single crystal based on solid solutions of alkali niobates-tantalates with the perovskite-type structure. In the second type of the layers, ferroelectric ceramic rods in the form of an elliptic cylinder are regularly aligned in a large polymer matrix, and the ceramic component is chosen among the perovskite-type compositions being either leaf-free or lead-containing. The hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients dh* and gh*, related figure of merit dh*gh*, and their non-monotonic behaviour are studied by taking an orientation effect into account. This orientation effect is caused by rotations of the ceramic rod bases in the polymer medium. The aforementioned hydrostatic parameters are compared to those of the conventional two-component ceramic-polymer composites, and some advantages of the studied lead-free 2–1–2 composites are discussed. These novel composites are suitable for hydroacoustic applications.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- 2–2-type Composite

- 2–1–2 Composite

- Hydrostatic Piezoelectric Coefficient

- Figure of Merit (FOM)

- Orientation Effect

1 Introduction

The piezo-active 2–2-type composites are widespread [1,2,3,4] and attractive due to their important electromechanical properties, large energy-harvesting figures of merit (FOM), hydrostatic parameters [5,6,7] etc. As is known, the 2–2 connectivity pattern [8] means a system of layers of two types (or two components of the composite), and each of these layers is distributed continuously along two axes of a rectangular coordinate system (X1X2X3). Modifications of the traditional laminar structure of the 2–2 composite [5, 8] are concerned with adding a third component or with forming a porous structure in one of the layer types [4, 7]. The conventional piezo-active 2–2 composite contains the ferroelectric (FE) ceramic and polymer layers that are usually parallel-connected [1, 2, 5] to facilitate a poling process. In the 2000–2010s, numerous examples of a performance of the 2–2-type composites based on FE single crystals (SCs) were discussed (see, for instance, Refs. 3, 6, 7). Very recently, a novel three-component lead-free composite with 2–1–2 connectivity was put forward, and its piezoelectric performance and hydrostatic parameters were analysed in work [9]. The 2–1–2 composite is characterised by the system of the parallel-connected layers of two types or by three components, namely, FE SC, piezoelectric SC and polymer. As shown in work [9], a new orientation effect in the 2–1–2 composite is associated with rotations of the piezoelectric SC rod bases in the polymer medium, and this influences the elastic properties and piezoelectric anisotropy in the SC/polymer layers and, therefore, the piezoelectric performance and hydrostatic response of the 2–1–2 composite as a whole.

However, to date no attempts were made to analyse examples of the 2–1–2 composite containing materials with two FE components, for instance, SC and ceramic in the adjacent layers. In fact, the chapter reports our results

-

(i)

on the orientation effect in the context of the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients and FOM of the 2–1–2 FE SC/FE ceramic/ polymer composite and

-

(ii)

on the comparison of the hydrostatic parameters of the similar 2–1–2 FE SC/FE ceramic/polymer composites that differ by their FE ceramic components.

2 Model of the Piezo-Active 2–1–2 Composite, Its Effective Properties, Hydrostatic Parameters and Components

2.1 Model Concepts, Effective Electromechanical Properties and Related Hydrostatic Parameters

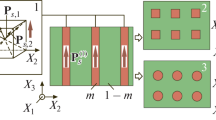

The 2–1–2 FE SC/FE ceramic/polymer composite studied by us represents the system of the parallel-connected layers of two types (Fig. 1). These layers are arranged periodically along the OX1 axis of the rectangular coordinate system (X1X2X3), and planar interfaces between the layers obey the condition x1 = const. In the layer of the first type (LFT), there is ferroelectric domain-engineered SC with the spontaneous polarisation vector Ps(1) || OX3, see inset 1 in Fig. 1. The crystallographic directions [h k l] shown in inset 1 of Fig. 1 are related to the perovskite unit cell. The main crystallographic axes X, Y and Z of domain-engineered SC in each LFT are oriented as follows: X || [1 0 0], Y || [0 1 0] and Z || [0 0 1].

The layer of the second type (LST) is regarded as a system of the aligned FE ceramic rods that are continuous along the OX3 axis and periodically arranged in a large polymer matrix, see inset 2 in Fig. 1. The remanent polarisation vector Pr(2) of each ceramic rod is parallel to the OX3 axis. The LST can be characterised as a composite with 1–3 connectivity in accordance with concepts [8]. Each rod in the LST is in the form of an elliptic cylinder with semiaxes a1 and a2 of the rod base. The aspect ratio of each rod base is ηc = a1/a2. In the LST, a rotation of each ceramic rod around OX3 in the polymer medium is described in terms of the angle γ (see inset 3 in Fig. 1). The poling axis of the composite sample as a whole (Fig. 1) is OX3.

Schematic of a 2–1–2 composite. m and 1 – m are volume fractions of the LFTs and LSTs, respectively. In inset 1, the domain-engineered SC component is schematically shown. In inset 2, the FE ceramic/polymer LST is shown. Where mc and 1 – mc are volume fractions of FE ceramic and polymer, respectively. In inset 3, the orientation of the elliptic cross section of the FE ceramic rod in the LST is shown, where a1 and a2 are semiaxes of the ellipse (or the ceramic rod base), and γ is the rotation angle.

This coordinate axis is parallel to both Ps(1) and Pr(2), and perpendicular to electrodes applied to this sample. We note that the present orientation of the Ps(1) and Pr(2) vectors in the adjacent layers of the composite sample facilitates the poling process in an external electric field E || OX3.

Effective electromechanical (i.e. elastic, piezoelectric and dielectric) properties of the 2–1–2 composite shown in Fig. 1 are found in two stages as follows. In the first stage, the effective field method [5, 10] is applied for evaluating the effective electromechanical properties of the LST (or the 1–3 ceramic/polymer composite). An electromechanical interaction between the FE ceramic rods (that are piezoelectric) in a large polymer matrix (that is either isotropic or transversely isotropic) is taken into account. The effective electromechanical properties of the LST shown in inset 2 of Fig. 1 are given by the matrix

In Eq. (1), || K(c) || and || K(p) || are 9 × 9 matrices with electromechanical constants of FE ceramic and polymer, respectively, mc is the volume fraction of FE ceramic in each LST, || I || is the identity matrix, and || S || is the matrix that contains the electroelastic Eshelby tensor components [11]. The || S || matrix depends on the electromechanical properties of the polymer component (i.e., elements of || K(p) ||) and the aspect ratio ηc of the FE ceramic rod base. A full set of electromechanical properties of the LST is given by the || K(2) || matrix that contains elastic moduli cab(2),E at electric field E = const, piezoelectric coefficients eij(2) and dielectric permittivities εpp(2),ξ at mechanical strain ξ = const. The electromechanical properties of the LST depend on the volume fraction mc of FE ceramic in the LST and on the aspect ratio ηc of the FE ceramic rod base. After this procedure of evaluations according to Eq. (1), the electromechanical properties of the LST are represented in the coordinate system (X1X2X3) by taking the rotation mode into account, see inset 3 in Fig. 1.

In the second stage of our revaluations, the matrix method [5, 7, 12/] is applied to the laminar structure of the 2–1–2 composite (Fig. 1). An electromechanical interaction between the piezoelectric LFTs and piezoelectric LSTs is taken into account. The effective electromechanical properties of the composite are described by the 9 × 9 matrix

In Eq. (2), || C(1) || and || C(2) || characterise the electromechanical properties of the LFT and LST, respectively, m is the volume fraction of the LFT, || M || is concerned with the electric and mechanical boundary conditions [5, 7, 12] at interfaces x1 = const (Fig. 1), and || I || is the identity matrix. A transition from the set of electromechanical constants involved in || K(2) || from Eq. (1) to the set of electromechanical constants from || C(2) || in Eq. (2) is carried out by using formulae [13] for a piezoelectric medium. The || C* || matrix from Eq. (2) is written in the general form as

and contains the full set of the elastic compliances \(s_{ab}^{*E}\) at electric field E = const, piezoelectric coefficients \(d_{ij}^{*}\) and dielectric permittivities \(\varepsilon_{fh}^{*\sigma }\) at mechanical stress σ = const. Superscript ‘t’ in Eq. (3) denotes the matrix transposition. The effective electromechanical properties [or elements of the || C* || matrix from Eqs. (2) and (3)] can be also written as Π*(m, mc, γ, ηc). The properties of the 2–1–2 composite (Fig. 1) are found in the longwave approximation [5, 7], i.e. on condition that a wavelength of an external acoustic field is much more than a width of each layer of the composite sample.

Based on the effective electromechanical properties Π*(m, mc, γ, ηc) of the 2–1–2 composite [or matrix elements of || C* || from Eq. (2)], we find and analyse the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients

and related hydrostatic FOM

of the composite. The piezoelectric voltage coefficients g3j* from Eqs. (4) are evaluated by using the formula

that illustrates the relationship between the piezoelectric and dielectric properties [17]. In Eq. (6), dfk* and εfj*σ are elements of the || C* || matrix from Eq. (2). The piezoelectric coefficients dh* and gh* from Eqs. (4) characterise the hydrostatic activity and sensitivity, respectively. At hydrostatic loading, the related FOM (Qh*)2 from Eq. (5) is important to estimate a signal/noise ratio of a hydrophone [19] and to describe an effectiveness of a mechanical-to-electric energy conversion due to the piezoelectric effect.

2.2 Components of 2–1–2 Composites

The main component of the studied 2–1–2 composites is lead-free FE SC that forms the LFT. Among potential components to be of interest in the sense of the eco-friendly and piezoelectric characteristics, we choose the [0 0 1]-poled domain-engineered [Lix(K1-yNay)1-x](Nb1-zTaz)O3:Mn (KNNTL-Mn) SC [15] with the perovskite-type structure, see the full set of electromechanical constants in Table 1. Herewith we note that the longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient d33 of this lead-free [0 0 1]-poled KNNTL-Mn SC [15] is larger than d33 of many conventional poled FE ceramics with the perovskite-type structure, e.g. ZTS-19, modified PbTiO3, PZT-4, PZT-5, and PZT-5A ceramics [5, 6].

In Table 2, the full sets of electromechanical constants of poled FE ceramics with the perovskite-type structure [16,17,18] are given. These constants are involved in the | K(c) || matrix from Eq. (1). For comparison, we consider the sets of constants of two lead-free compositions (see KNNLT and KNN–KCN in Table 2) and a lead-containing modified PbTiO3. These ceramic components exhibit a smaller piezoelectric effect in comparison to KNNTL-Mn from the LFT. It should be noted that the transverse piezoelectric coefficient e31 of the aforementioned ceramic components can be either negative or positive. In general, the FE ceramic components from Table 2 represent different examples of the anisotropy of the piezoelectric and elastic properties that can influence the electromechanical properties of the LST to a certain degree. We add that the piezoelectric activity of these FE ceramic components from the LST is lower than the piezoelectric activity of KNNTL-Mn SC from the LFT. For instance, poled KNNTL ceramic is characterised by the longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient d33 = 174 pC/N, and this is the largest d33 value related to the FE ceramic components listed in Table 2.

In Table 3, we show the elastic and dielectric properties of polyethylene (PE) being the piezo-passive polymer component [7, 19] of the studied 2–1–2 composites. The set of constants of PE from Table 3 is included in the || K(P) || matrix from Eq. (1) to find the effective electromechanical properties of the LST.

3 Piezoelectric Properties and Hydrostatic Parameters of Composites

In Sect. 2, we present and discuss our new results on the effective piezoelectric properties and hydrostatic parameters (4) and (5) of the 2–1–2 KNNTL-Mn SC/FE ceramic/PE composites, where the FE ceramic component in the LST is one of those listed in Table 2. This means that the composites containing either KNNLT or KNN–KCN ceramic in the LST are lead-free in contrast to the composite containing modified PbTiO3 ceramic in the same LST. In the LST of the composite, we consider the cylindrical FE ceramic rods with the large aspect ratio of the rod base ηc = 100. This enables one to achieve a large elastic anisotropy even at small volume fractions mc of the rods [9] in the LST. A variation of the volume fraction m of the FE SC component in the composite and changes in the rotation angle γ in the LST are important to achieve maxima of the hydrostatic parameters from Eqs. (4) and (5) at ηc = const and mc = const. Below we show graphs concerned with the orientation effect due the rotation of the rod bases in the LST (see inset 3 in Fig. 1) at fixed volume fractions m of the FC SC component. We consider the hydrostatic parameters of the 2–1–2 composite at m = 0.05–0.30, i.e., at volume fractions of the LSTs from 0.70 to 0.95.

Graphs in Fig. 2 show changes in the hydrostatic parameters (4) and (5) of the lead-free KNNLT-Mn SC/KNNTL ceramic/PE composite at small volume fractions mc of KNNLT in the LST. An increase of the volume fraction mc of the ceramic component in the LST leads to a decrease of the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients dh*, gh* and FOM (Qh*)2 of the composite (cf. Figure 2, a and 2, c, Fig. 2, c and 2, e, Fig. 2, b and 2, d, and so on). This decrease is observed even at the relatively small volume fractions mc = 0.03–0.05. A simple comparison of the elastic properties of the ceramic and polymer components (see Tables 2 and 3) suggests that the volume-fraction level mc = 0.03–0.05 is of interest because the elastic moduli cab(2),E of the LST become by about an order-of-magnitude larger in comparison to cab of PE that is regarded as a matrix component in the LST. Such specifics of the elastic properties of the LST and the rotation of the ceramic rod bases therein influence together and lead to a non-monotonic behaviour of the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients and dh* and gh* of the composite at variations of the rotation angle γ. Based on the composite structure (Fig. 1) and symmetry of the components, one can state that the hydrostatic parameters Πh* obey the condition:

Orientation (γ) dependences of hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients dh* (in pC/N, graphs a, c and e) and gh* (in mV.m/N, graphs b, d and f) of the 2–1–2 KNNTL-Mn SC/KNNLT ceramic/PE composite at the volume fraction of FE ceramic mc = 0.03 (graphs a and b), mc = 0.04 (graphs c and d). or mc = 0.05 (graphs e and f) in the LST.

This enables us to analyse the orientation effect in the studied 2–1–2 composites at rotation angles γ from 0° to 90°.

The change of the sequence of curves 1–6 related to gh* in comparison to dh* (cf. Figure 2, a and 2, b) is concerned with an effect of the combination of the piezoelectric and dielectric properties [5,6,7], and this effect is noticeable at the small volume fraction m of SC. Taking the composite structure, components and symmetry into account, we represent a relationship between the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients from Eqs. (4) in accordance with Eq. (6) as follows:

Graphs in Fig. 2 enable us to conclude that the presence of two related lead-free components (namely, KNNTL-Mn SC and KNNLT ceramic in the adjacent layers, see chemical compositions in footnotes in Tables 1 and 2) does not lead to a serious worsening of the piezoelectric performance of the composite. The aforementioned lead-free components play different roles in the 2–1–2 composite structure (Fig. 1) and influence the piezoelectric hydrostatic response in different ways.

Table 4 illustrates the electromechanical properties of the LST where one of the three FE ceramic components from Table 2 is present, and the volume fraction mc of the ceramic component is small. It should be noted that even at mc = 0.03 or 0.05, the LST is characterised by an appreciable elastic anisotropy, and only the elastic compliance s22(2),E undergoes minor changes when changing the ceramic component at mc = const (see Table 4). Such a behaviour of s22(2),E is inextricably linked to the orientation of the ceramic rod base (see inset 3 in Fig. 1) at the rotation angle γ = 0°. In our opinion, the rotation of the rod base leads to changes in the elastic anisotropy of the LST, however this anisotropy remains noticeable and influences the piezoelectric coefficients d31* and d32* from Eqs. (4) and, therefore, the hydrostatic parameters of the composite.

In Fig. 3, examples of the orientation (γ) dependence of the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 are graphically represented for the three studied 2–1–2 composites. In these composites, the FE ceramic component in the LST is either lead-free (KNNLT or KNN-KCN) or lead-containing, based on PbTiO3 (see chemical compositions in footnotes to Table 2). A simple comparison of Fig. 3, a–c to Fig. 2 shows that the sequence of curves 1–6 related to gh* remains similar in the case of (Qh*)2. By analogy with the hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficient gh* from Eq. (7), we write the expression for the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 as follows:

The appreciable effect of the combination of the piezoelectric and dielectric properties in the 2–1–2 composite influences not only its hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficient gh*, but also the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 from Eqs. (5) and (8) largely at volume fractions m << 1. Such volume fractions m cause the small dielectric permittivity ε33*σ of the composite in comparison to ε33(1),σ of the main component (or the LFT).

As follows from the behaviour of the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 in Fig. 3, the lead-free 2–1–2 composites are characterised by the larger (Qh*)2 values in comparison to (Qh*)2 of the composite containing modified PbTiO3 ceramic in the LST. This is caused by the large elastic moduli cabE of poled modified PbTiO3 ceramic and by its smaller piezoelectric activity [18] in comparison to the performance of KNNLT and KNN-KCN ceramics [16, 17] in the poled state.

Comparing our results on the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 of the 2–1–2 composites to literature data, we note that the (Qh*)2 values of the studied lead-free composites (Fig. 3, a–d) are comparable to (Qh*)2 of an oriented 2–2 PZT ceramic/polymer composite [2], (Qh*)2 of 2–2 composites based on relaxor-ferroelectric [0 1 1]-poled PMN–xPT SCs [3], and (Qh*)2 of a PZT-based composite with a spiral structure [20]. Moreover, the (Qh*)2 values of the lead-free 2–1–2 composites (Fig. 3, a–d) are a few times larger than (Qh*)2 of traditional 2–2 or 1–3 FE ceramic/polymer composites [1, 2] based on lead-containing PZT-type ceramics. We emphasise that the aforementioned composites from work [1,2,3, 20] have lead-containing components with a high piezoelectric activity.

The hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficient gh* of the 2–1–2 composite containing lead-free KNNTL ceramic (see Fig. 2, b and d) is comparable to gh* of 2–0–2–0 composites based on lead-containing PZT-type ceramics [21]. In the 2–0–2–0 composites from work [21], the large level of gh* is achieved due to systems of pores in the ceramic and polymer layers. The large gh* and (Qh*)2 values of the studied lead-free 2–1–2 composites (see Fig. 2, b, d and f, and Fig. 3, a–d) make these materials suitable as active elements of modern hydrophones and hydroacoustic systems.

Orientation (γ) dependences of the hydrostatic FOM (Qh*)2 (in 10 Pa−1) of the 2–1–2 KNNTL-Mn SC/KNNLT ceramic/PE composite (graphs a–c), KNNTL-Mn SC/KNN–KCN ceramic/PE composite (graph d) and KNNTL-Mn SC/modified PbTiO3 ceramic/PE composite (graph e) at the volume fraction of ceramic mc = 0.03 (graphs a, d and e), mc = 0.04 (graph b). or mc = 0.05 (graph c) in the LST.

4 Conclusion

The present chapter has been devoted to the new 2–1–2 composite structure (Fig. 1) and hydrostatic piezoelectric response of the related composites with two FE components, namely, SC and ceramic. In the 2–1–2 composite, the LFT is [0 0 1]-poled domain-engineered dead-free KNNTL-Mn SC with a high piezoelectric activity. The LST represents the 1–3 FE ceramic/PE composite with the piezoelectric (poled FE ceramic) rods in the form of the elliptic cylinder, and this microgeometry of the LST along with the orientation effect plays the key role in forming the anisotropic elastic properties. The elastic properties of the LST influence the piezoelectric performance and related hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficients dh* and gh* of the 2–1–2 composite, especially at volume fractions of SC m << 1.

The large hydrostatic parameters dh* > 100 pC/N and (Qh*)2 ≈ 20.10–12 Pa−1 of the studied 2–1–2 composites (Figs. 2 and 3) are achieved due to high-performance [0 0 1]-poled KNNTL-Mn SC in the LFT, the 1–3 FE ceramic/PE composite in the LST and the orientation effect associated with the rotation of the ceramic rod base in the LST (see inset 3 in Fig. 1). However the 2–1–2 composite that contains modified PbTiO3 ceramic in the rods of the LST looks less preferable as compared to the similar lead-free composites studied by us, and this is accounted for by the smaller FOM (Qh*)2 of the PbTiO3-containing composite (see Fig. 3). This decrease of (Qh*)2 is achieved due to the smaller elastic compliances s11(2),E and s22(2),E and piezoelectric coefficient d33(2) of the LST that contains modified PbTiO3 ceramic (Table 4). This well-known lead-containing ceramic component is characterised by the smaller piezoelectric coefficients |d3j| [18] in comparison to those of the lead-free FE ceramic components [16, 17] from Table 2. The large hydrostatic piezoelectric coefficient dh* and FOM (Qh*)2 of the studied lead-free 2–1–2 composites enable us to underline their advantages over various piezo-active 2–2-type composites [1,2,3,4] used in hydrophones, sensors, transducers, and other devices.

In general, the present study shows an importance of the novel 2–1–2 composites with two FE components that enable one to improve the piezoelectric hydrostatic response and FOM. The sets of the large hydrostatic parameters Πh* of the studied lead-free 2–1–2 composites (see Figs. 2 and 3) make these piezoelectric materials competitive and can be of value in hydroacoustic applications.

References

Akdogan, E.K., Allahverdi, M., Safari, A.: Piezoelectric composites for sensor and actuator applications. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 52(5), 746–775 (2005)

Safari, A., Allahverdi, M., Akdogan, E.K.: Solid freeform fabrication of piezoelectric sensors and actuators. J. Mater. Sci. 41(1), 177–198 (2006)

Li, L., Zhang, S., Xu, Z., Geng, X., Luo, J., Shrout, T.: Hydrostatic piezoelectric properties of [011] poled Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 single crystals and 2–2 lamellar composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104(3), 032909 (2014)

Dongyu, X., Xin, C., Shifeng, H.: Investigation of inorganic fillers on properties of 2–2 connectivity cement/polymer based piezoelectric composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 94, 678–683 (2015)

Topolov, V.Yu., Bowen, C.R.: Electromechanical Properties in Composites Based on Ferroelectrics. Springer, London (2009)

Bowen, C.R., Topolov, V.Yu., Kim, H.A.: Modern Piezoelectric Energy-Harvesting Materials. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, Cham (2016)

Roscow, J.I., Topolov, V.Yu., Bowen, C.R., Khanbareh, H.: Innovative Piezo-active Composites and Their Structure – Property Relationships. World Scientific, Singapore (2022)

Newnham, R.E., Skinner, D.P., Cross, L.E.: Connectivity and piezoelectric – pyroelectric composites. Mater. Res. Bull. 13(5), 525–536 (1978)

Topolov, V.Yu.: Novel lead-free 2–1–2 composite: predicted high piezoelectric sensitivity and significant hydrostatic response. Smart Mater. Struct. 32(8), 085010 (2023)

Kuo, W.-S., Huang, J.H.: On the effective electroelastic properties of piezoelectric composites containing spatially oriented inclusions. Internat. J. Solid Struct. 34(19), 2445–2461 (1997)

Huang, J.H., Kuo, W.-S.: Micromechanics determination of the effective properties of piezoelectric composites containing spatially oriented short fibers. Acta Mater. 44(12), 4889–4898 (1996)

Levassort, F., Lethiecq, M., Certon, D., Patat, F.: A matrix method for modeling electroacoustic moduli of 0–3 piezocomposites. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 44(2), 445–452 (1997)

Ikeda, T.: Fundamentals of Piezoelectricity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, Toronto (1990)

Sherman, C.H., Butler, J.L.: Transducers and Arrays for Underwater Sound. Springer, New York (2007)

Huo, X., et al.: (K, Na, Li)(Nb, Ta)O3: Mn lead-free single crystal with high piezoelectric properties. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 98(6), 1829–1835 (2015)

Yao, F.-Z., Wang, K., Li, J.-F.: Comprehensive investigation of elastic and electrical properties of Li/Ta-modified (K, Na)NbO3 lead-free piezoceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 113(17), 174105 (2013)

Zhay, S., Lim, J.B., Lee, H.J., Shrout, T.R.: Characterization of hard piezoelectric lead-free ceramics. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 56(8), 1523–1527 (2009)

Ikegami, S., Ueda, I., Nagata, T.: Electromechanical properties of PbTiO3 ceramics containing La and Mn. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 50(4A), 1060–1066 (1971)

Evans, K.E., Alderson, K.L.: The static and dynamic moduli of auxetic microporous polyethylene. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 11(22), 1721–1724 (1992)

Wu, J., Ma, W., Chi, M., Wang, S., Zhang, P.: Effect of surface modification of ferroelectric ceramic component on the properties of PZT-type/epoxy piezoelectric composite with spiral structure. J. Alloys Compd. 820, 153362 (2020)

Nesterov, A.A., Topolov, V.Yu., Tolstunov, M.I., Isaeva, A.N.: Longitudinal piezoelectric effect and hydrostatic response in novel laminar composites based on ferroelectric ceramics. Ceram. Internat. 45(17), 22241–22248 (2019)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. A. E. Panich and Prof. Dr. I. A. Parinov (Southern Federal University, Russia), Prof. Dr C. R. Bowen (University of Bath, UK), and Prof. Dr. P. Bisegna (University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy) for their interest in the field of modern piezo-active composites. This research was supported by the Southern Federal University (research topic “Development and Materials-Science Substantiation of the Creation of Materials and Products Based on Piezoelectric Ceramics Using Additive Technologies”, contract No. 176/22-D, July 11th, 2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Topolov, V.Y., Kovrigina, S.A. (2024). Novel Lead-Free 2–2-Type Composites with High Piezoelectric Sensitivity and Strong Hydrostatic Response: Examples of 2–1–2 Connectivity. In: Parinov, I.A., Chang, SH., Putri, E.P. (eds) Physics and Mechanics of New Materials and Their Applications. PHENMA 2023. Springer Proceedings in Materials, vol 41. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52239-0_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52239-0_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-52238-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-52239-0

eBook Packages: Chemistry and Materials ScienceChemistry and Material Science (R0)