Abstract

This chapter focuses on gendered norms of caregiving with regard to parenting practices, focusing on how “mothers” and “fathers” are positioned in parenting discourses. Its placement in a volume on gender and power is pertinent given that we often see gendered stereotypes related to caring come into play in early parenting in what were regarded as “equal” partnerships before children. The chapter moves through a number of areas, using empirical examples. It begins by exploring contemporary parenting culture and parenting ideologies, before considering the discourse of the “maternal.” From here, it moves to a consideration of fathers in the primary caregiving role and how, in these families at least, parenting can be seen as a more equitable, joint “partnership.” Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns that occurred in many countries across the world, which demonstrated a return to traditional gendered norms of caregiving and had an unequal impact on mothers.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This chapter focuses on gender with regard to pregnancy and caregiving/parenting practices. Its placement in a volume on gender and power is pertinent given that we often see gendered stereotypes related to caring come into play in early parenting in what were regarded as ‘equal’ partnerships before children (Faircloth, 2020; Miller, 2017). The focus in this chapter is on heterosexual partnerships where there is a ‘mother’ and a ‘father’ to explore gendered practices in caregiving. There is a strong research field on lesbian and gay parenting that potentially demonstrates more equal caregiving practices (Ryan-Flood, 2009). Lesbian and gay parenting arguably demonstrates a deliberateness and intentionality of kinship parenting rather than a reliance of biological factors (Weston, 1991). Susan Golombok’s work (2015) on new family forms indicates more positive parental well-being and parenting from parents in gay father families compared with heterosexual families.

With regard to power, as others have noted (e.g., Pilcher & Whelehan, 2004), power is inherently complex to define and tends to be fluid. Acting from a post-structuralist perspective that considers the ways in which power is actioned in discourse, this chapter has its focus is on how ‘parents’ are being both positioned in, and potentially resisting, particular discourses. The chapter considers discourses around ‘parenting,’ ‘caregiving,’ ‘mothers,’ and ‘fathers.’ The first two of these concepts are presented in gender neutral terminology. However, parenting and caring practices are anything but neutral and, as others have noted (e.g., Sunderland, 2006) discourses of parenting tend to be more tied to motherhood than fatherhood. Some of these differences in caregiving amounts may be justified through structural inequalities, for example, the ‘motherhood penalty’ (Budig & England, 2001) where mothers traditionally appeared to have more responsibility for caring and are more likely to opt for part-time or flexible working hours, partly due to previous gender pay gaps and societal expectations on gender and caregiving. As Williams (2010) argues when looking at maternal stereotyping in the workplace, there is a ‘maternal wall’ of discrimination whereby working mothers may be seen as having reduced capacity for the workplace and being likely to take time away from the office for caregiving responsibilities. As Yarwood and Locke (2016) and Locke and Yarwood (2017) noted, these gendered patterns of caregiving appear even in families where parenting is supposedly at least equally ‘shared.’ The gender gap in family responsibilities has been gradually narrowing (Pailhé et al., 2021). However, parenting responsibilities tend to still be predicated on traditional mother/father lines (Sullivan et al., 2018). I will reflect on this further on in the chapter.

As will be discussed, the COVID-19 pandemic across much of the globe starting from the Spring of 2020 laid bare the tensions inherent in gender and caregiving responsibilities where, for example, in the UK there is now clear evidence that the lockdowns had a larger impact on working mothers rather than fathers who were disproportionally impacted with balancing childcare, homeschooling, and precarity in the workplace, leading to suggestion of knock effects on mental health (Kirwin & Ettinger, 2022). The focus in this chapter is one of exploring these gendered constructions of caregiving and unpacking some of the underlying assumptions inherent within these discourses.

In this chapter, I offer an exploration of caregiving and parental identities and situate these within contemporary parenting ideologies and discourses. It uses as exemplars contemporary research work to demonstrate common discourses around gender and parenting. The first exemplar concerns the ‘maternalisation’ of parenting culture, from the ways in which ‘parenting’ and ‘mothering’ become synonymous, in terms of parenting advice and responsibility. The second exemplar is a study conducted on fathers who took on the primary caregiving role for their children, so-called, Stay-At-Home-Dads (SAHDs) and contextualizes findings from this work within a wider discussion of parenting roles, gendered identities, and intersectional concerns. The chapter discusses this work within the wider context of gender, power, and parenting, finally situating it as an exemplar in the UK lockdowns during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021.

Contemporary Parenting Culture and Ideologies

Parenting does not occur in a vacuum and any aspect of knowledge and advice that we are given contains aspects that are culturally, societally, and historically located (e.g., Apple, 1987; King, 2015). It is also pertinent to remember that ‘parenting’ does not form a hegemonic discourse, despite it often being seemingly reported in these ways. Indeed parenting discourses will differ in terms of intersections with gender, whether ‘mothering’ or ‘fathering’, and social class (Dolan, 2014; Gillies, 2007; Shirani et al., 2012), age (Budds et al., 2016; Eerola & Huttunen, 2011; Locke & Budds, 2013), ethnicity (Hauari & Hollingworth, 2009), sexual orientation (Johansson, 2011; Ryan-Flood, 2009) as well as paid work status (Christopher, 2012; Haywood & Mac an Ghaill, 2003), with all of these differing issues themselves potentially, in turn, may intersect with gendered norms in terms of masculinities and femininities. I will unpack and discuss some of these issues further within this chapter.

There are a number of parenting ideologies that frame discussions on contemporary parenting practices. Within the field of Parenting Culture Studies (e.g., Lee et al., 2014), we can see how dominant discourses around parenting are located within risk behaviors and risk management, drawing on work from Frank Furedi on “Paranoid Parenting” (2002) in which he notes parenting has been reconstructed as a “troublesome enterprise….. (which) systematically deskills mothers and fathers” (page 201). In this vein, mothers are cast as ‘risk managers’ (Lee et al., 2010) in that their role is to make ‘informed choices’ on what the appropriate actions are in their parenting practice. Similarly, Daminger (2019) terms mothers as often acting as ‘project managers’ in the household in that they are managing the decisions and tasks that the household needs to run effectively. Note in all of these examples, that the responsibility for parenting often lies with the mother. This is reflected widely across research literature as well as advice around parenting, as this chapter will demonstrate.

Contemporary parenting culture has been regarded as being ‘intensive.’ The contemporary concept of ‘intensive mothering’ came in formative and ground-breaking work by Sharon Hays (1996) on the ‘Cultural contradictions of motherhood.’ For Hays, the mother (note not the father here), despite other roles and pressures in her life, needs to be self-sacrificial, full-time (even if employed), and child-centered in her parenting practices. This concept of ‘intensive motherhood’ is incredibly influential and has been adapted in more recent years to fit more nuanced aspects of mothering practice. For example, Christopher (2012) talks in similar terms of ‘extensive’ mothering to explain how working mothers performs ‘extensive’ duties of caring for their children demonstrate their ‘good’ mothering. Similarly, Joan Wolf (2011) renamed this ‘total’ motherhood in reference to the care work associated with full-time breastfeeding of a small infant. Finally, French philosopher, Elisabeth Badinter, refers to the current mothering ideologies as ‘overzealous’ (2012). As research continues to demonstrate, the norm toward gendered caregiving where perceptions of ‘good’ mothers are commensurate with full-time stay-at-home mothers, rather than those in employment (e.g., Gorman & Fritzsche, 2002), is still clearly evident across parenting discourses. Women who do not or cannot live up to this idealized form of motherhood may feel judged as being a ‘bad’ (or inadequate) mother (Arendell, 2000; Christopher, 2012).

Within contemporary parenting ideologies, it becomes apparent that there is almost a kind of surveillance on parenting practices (Gross & Pattison, 2006). These include decisions on how the baby is fed (Lee, 2007; Knaak, 2010; Locke, 2015, 2017), the timing of pregnancy (Budds et al., 2016) and women’s behaviors pre- (Budds, 2021; Waggoner, 2017) and during pregnancy (Locke, 2023; Lowe & Lee, 2010). Working from a neoliberal standpoint, there is a presumption that we are citizens of a liberal democracy making choices about our lives and our health that are based on accurate and true information that we receive in order to avoid or minimize the risk of harm to ourselves or our families (Ayo, 2012). For example, the dominant discourses that are present within current health promotion practices that we find are of ‘informed choice’ and risk. The way that parenting discourses have become bound up with notions of risk links in with Foucault’s notion of governmentality (Foucault, 1991; Lupton, 1999) and, in turn, many of these discourses become tied up with health behaviors related to parenting. Furthermore, aspects of accountability (and potential blame) for making the ‘wrong’ choice (Phipps, 2014) are inherent throughout contemporary parenting discourses.

‘Parenting’ and the Discourse of the ‘Maternal’

Much of the information and advice around parenting issues is delivered to a gender neutral ‘parent.’ However, the terminology of parenting is not without issue or debate. As, in the cases above, much of the parenting literature relates specifically to ‘mothering’ as a practice or ‘mother’ as the main caregiver. When we consider the language of parenting, we can often see somewhat stereotypical gendered constructions of caregiving and responsibility inherent throughout. As Kate Boyer (2018) notes, childcare predominantly remains ‘women’s work.’

Baraitser and Spigel defined an interest in the ‘maternal’ as, among other things, a ‘unique form of care labour’ (2011, p. 825). One way in which this has been conceptualized in the feminist literature is to consider a discourse of the ‘maternal,’ most famously suggested by Ruddick (1995) in her theorizing of ‘maternal’ embodied, nurturing caregiving. Therefore, from this perspective ‘maternal’ defines a set of practices associated with nurturing behaviors, most commonly linked with raising children, and most often related to ‘mothers’ as engaging in these caregiving practices. I will pick this up again later in the chapter in my discussion of primary caregiver fathers, i.e., stay-at-home-dads.

As the research literature demonstrates, infant feeding practices are one key place where intensive mothering ideologies are played out in full (e.g., Wolf, 2011). We now consider an example taken from a newspaper study of media representations of a method of infant feeding called ‘baby-led weaning’ (Locke, 2015) where I considered how baby-led weaning was both endorsed and resisted as a means of displaying ‘good motherhood’ in contemporary parenting culture. If there was any doubt of the ‘maternalisation’ of parenting culture and the prevalent discourses around gendered binaries of care, this article from the UK press makes it clear. It focuses on ‘parenting’ advice to the new ‘parents,’ in this case, Prince William and Kate Middleton, the (now) Prince and Princess of Wales, after the birth of their first child, Prince George.

Official guidelines say six months is the earliest parents should start giving their baby food other than milk, although a study earlier this summer revealed that 96 percent ignore that advice and start earlier. Kate will soon realise that there is a huge debate about how to wean a baby: in one corner are fans of traditional spoon-fed puree; in the other are advocates of a new approach called Baby-Led Weaning, where small chunks of food are placed in front of your baby and it’s up to him whether he eats it or throws it on the floor. It’s a messy business, and although Kate presumably won’t have to worry about extracting chewed green beans from the crevices in the high chair, BLW is a step too far for many mums. (EXCERPT 1: The Telegraph, 21 July 2013, UK)

As we see throughout the extract, when giving advice to the gender neutral, ‘new parents,’ the focus is clearly on Kate as the mother, who is explicitly cited twice, as the one who the advice is specifically aimed at. There is a presumption in parenting discourses whereby they tend to automatically defer to the mother in terms of the receiver of parenting information and advice (Sunderland, 2006). This is one indication of the ways in which gendered constructions of caregiving are occurring in parenting information and practices. If we situate the advice alongside intensive mothering ideology, then we can see how the information is directed to the mother and how the mother takes this up in her performance of child-centered, intensive motherhood in order to fulfill her ‘good mothering’ identity.

The issue of ‘parenting’ discourse from some feminist perspectives can be problematic as it presupposes an equality within society that is clearly not there. As Arlie Hochschild (1990) noted some decades ago, women are commonly involved in the ‘Second Shift,’ that is, that once they have fulfilled working demands outside of the home, they come home to a ‘second shift’ of domesticity. Time use studies of housework and childcare within the home regularly demonstrate that women and mothers tend to perform more of these tasks (Bianchi et al., 2012; Sayer, 2005). This appears to be the case even within some homes where the father is the primary caregiver (Craig, 2006). Latshaw and Hale (2016) noted how in families where the mother was the breadwinner, once the mother returned to the home after a day in paid work, she took over the childcare. They argued that families were continuing to ‘do’ conventional gender despite having an alternative domestic setup. While this may be due in part to societal expectations on gender and domestic pursuits, as argued by some, (e.g., Hochschild, 1990), it also demonstrates the dominance of the ‘intensive’ (Hays, 1996) or ‘extensive’ (Christopher, 2012) mothering ideology, that the mother is performing her ‘good mothering’ role in this way.

Contemporary Fathering Discourses and Stay-at-Home-Dads

Despite the societal discourse around ‘involved fatherhood’ that is commonplace in many Western and industrialized cultures, there is evidence to suggest that discourses of the nurturing mother as primary caregiver are commonplace and evident throughout all aspects of parenting education and literature. Jane Sunderland’s (2000) work on contemporary parenting texts and magazines notes how fathers were often portrayed in these texts as “part-time,” “baby entertainers,” “line managers,” and “bumbling assistants” as opposed to equal carers. Similar points have been raised elsewhere, such as by Wall and Arnold’s (2007) study of the Canadian Press, whereby fathers are often portrayed in ‘fun’ playing roles with their children, while the mothers perform more nurturing tasks such as cooking and general day-to-day childcare.

In recent years in the UK, and elsewhere, there has been a documented rise in fathers who are taking on the primary caregiving role for their children. While some of this has been put down to a ‘de-gendering of parenting’ and the rise of involved fatherhood (Risman, 2009; Miller, 2010 on the un-doing or redoing of gender and caring), others have put the larger increases down to the global recession of 2008 or ‘man-cession’ as it was commonly reported in the print media (Locke, 2016) due to the apparent negative effect of the recession on male unemployment (Wall, 2009; c.f. Williams & Tait, 2011). Exact figures on the number of stay-at-home-fathers within the UK are hard to ascertain but a survey by insurance company Aviva in 2010 estimated that up to 1 in 7 fathers were taking on the primary caregiving role for their children. More recent figures from the Office of National Statistics in 2015 suggested that 225,000 men in the UK were economically inactive due to looking after their home and family (ONS, 2016). In the UK, a system of Shared Parental Leave was brought in half-way through the previous decade (Children and Families Act, 2014). Importantly, and in terms of societal responsibility and discourses around gender and parenting, all employed women maintained full eligibility for maternity leave and statutory maternity pay but could also choose to share the balance of the remaining leave with the other parent and pay, up to a total of 50 weeks of leave and 37 weeks of pay (Statutory Maternity Pay Rate). As Locke and Yarwood (2017) noted however, the introduction of SPL was a missed opportunity “to break down engrained ideological and political discourses of gendered work-family divisions” (page 9).

There are a plethora of research studies focusing on contemporary fathering and the rise of the ‘involved father.’ One such study (Henwood & Proctor, 2003) found that, in general, men placed less importance on their role as providers, and instead identified their role at home, as a father, as their main concern, comparing their role favorably with that of their fathers. Anna Dienhart suggests that despite talk of the “new father” and “working women,” “social discourse about the good provider role for men still seems deeply entrenched” (Dienhart, 1998, p. 23). Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that discourses of the nurturing mother as primary caregiver are commonplace and evident throughout all aspects of parenting education and literature, as we see with Sunderland’s (2000, 2006) work on depictions of fathers in parenting magazines. When we consider how the ideology of intensive parenting is being conceived, it is clearly focused toward motherhood, while ‘fatherhood’ is someone neglected, or indeed ‘insulated’ from this pressure (Shirani et al., 2012). Fathers themselves claim to be more involved in autonomous decision-making, rather than feeling pressured by expert advice and external judgment. However, given the gendered assumptions of parenting that inhabit our society, the reported differences in “actual” decision-making could explain this “insulation,” as it is the mother who is typically cast as the decision-maker for her children. As Henwood and Proctor (2003) noted two decades ago, this equity in decision-making was raised as a key tension in a sample of involved fathers (in heterosexual relationships). There is a small but growing literature around fathers in primary caregiving positions with the majority of that work focusing on single fathers or fathers who will take on the primary caregiving role for a limited time (Russell, 1999) instead of a permanent domestic setup, as is the case for many of the fathers using, for example in the UK, the Shared Parental Leave system. In addition, much of the work on contemporary fatherhood focuses on those in heterosexual relationships (e.g., Chesley, 2011; Miller, 2011). As Andrea Doucet (2006) noted almost two decades ago when considering the dilemma of gender ‘equality’ in parenting—there is no socially acceptable model for a mother as a secondary caregiver. This statement remains as true today where mothers taking on that role are somehow depicted as non-normative.

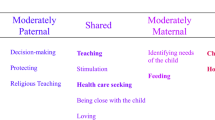

Parenting as Partnership: A Discourse of ‘We’

Drawing on interviews taken from a larger project looking at ‘stay-at-home-dads’ (SAHDs) in the UK that I conducted, we can explore gendered expectations of parental caregiving. While conducting the interviews, it became apparent that the fathers were talking within a discourse of ‘parenting.’ That is, when discussing their practices of caregiving for their children, the word most commonly used was ‘parenting’ and they talked in terms of collaborative decision-making between themselves and their ‘partners,’ in most cases, the mothers of the children (the majority of the sample identified as heterosexual).

It became clear for all of the fathers in relationships in the sample here, that ‘parenting’ was very much a joint venture and one that was enacted through discussions and agreement with their partners. The first excerpt is from a participant who has the pseudonym, Jim. He has two children and is one of the part-time working fathers in the sample. At the time of the interview, he was residing overseas but has been part-time and the primary caregiver since the children were very young in the UK. As interviewer, I ask about the ‘partnership’ side of parenting as Jim has been talking of parenting as collaborative all of the way through the interview. The interviewer’s talk is marked in bold.

- I::

-

Is parenting very much a kind of partnership between you two then do you think?

- J::

-

Tag team, yes it has to be, especially with these two. You know, we don’t have roles for ourselves but the kids have roles for us. The kids see us in doing different things and their ideas of what we do are quite set I think and they have said quite often you know, “Mum, why do you work all the time. Dad should be the one that works all the time, you should be at home.” Anna craves that. (EXCERPT 2, Jim, Interview 6)

This excerpt shows how for many of these families, the SAHDs formulate their parenting in terms of being a joint enterprise, a domestic ‘tag team’ that he humorously notes the need for their two particular children (daughters). What also becomes apparent here though is that although Jim and his partner have a clear partnership with a division of roles, the societal discourses of gendered caring are still very much felt within their family. He claims that their children portray parenting and the responsibilities very much in gendered norms of parenting in that the mother’s role is to not be working ‘all the time’ and she ‘should be at home,’ whereas the father’s role is one that is constructed as working ‘all the time.’ He backs this up that one of his daughters (“Anna”) “craves that,” i.e., inferring that she would prefer to have her mother at home, rather than her father. It is interesting that Jim’s excerpt suggests that children are aware of gendered norms toward caregiving and parenting when being raised in what is regarded as a non-traditional family. This points to the strength of the societal discourses of gendered parenting that permeate through much of our daily lives.

This parenting as partnership and the joint decision-making is evident throughout all of the interviews and another example is given below. In this excerpt, we hear from Craig, who, at the time of the interview, was the primary caregiver for two young children aged 16 months and 3 years of age. The three-year old attends preschool on a part-time basis. This excerpt deals with Craig’s reason for becoming the primary caregiver. Prior to becoming a SAHD, Craig and his partner were both in professional occupations.

one of the biggest reasons, actually is, my wife did suffer with post-natal depression and it’s funny because at first we were very, kind of, ‘Oh we don’t talk about this’ and ‘Well we’re managing. We’ll get through.’ And actually, as time has gone on, we sat down and thought, ‘Well actually, one of the best ways to deal with it is to be open and up front and talk about it.’ So, and actually that would have been one of the reasons why we decided to make the change. That and I’m a much better cook than my wife too ((laughs)). (EXCERPT 3, Craig, interview 3)

As we discussed earlier, there are strong societal gendered expectations of parenting where mothers are seen as natural nurturers while fathers are seen as providers (Hegewisch & Gornick, 2011; Thomson et al., 2011). As Locke (2016) observed, media representations of the reasons for becoming a primary caregiving father typically focus on monetary concerns as the sole issue. However, as noted elsewhere (Locke & Yarwood, 2017) and here, the reasons for taking on the primary caregiving role are diverse. In the case of Craig, he suggests a strong contributing factor in the decision was his wife’s post-natal depression during her second maternity leave and their decision for her to return to work early, while Craig took on the primary caregiving role. As becomes evident throughout all of the stay-at-home-fathers in the wider sample, the nurturing role of fatherhood and being in the position to develop this deep relationship with their children appears to be one of the paramount issues that emerges across the corpus. This stands in opposition to common media depictions of fatherhood (Locke, 2016) but reflects the growing literature on modern fatherhood whereby fathers are wanting to be involved, nurturing parents (Doucet, 2006; Finn & Henwood, 2009).

Much like Hays’ (1996), intensive mothering ideology, ‘good’ parenting practices are full-time, intensive, and child-centered, and for the SAHDs interviews presented in this chapter, the importance that they placed on performing a ‘good father’ role appeared to be paramount (see also Henwood & Proctor, 2003). The nurturing nature of the parenting role is one that is typically bestowed on the mother, therefore stay-at-home-fathers have to navigate a myriad of discourses of caregiving, parenting, and traditional gendered norms of what mothers and fathers do in their accounts of caring for their children. In the interviews that I conducted, there was a clear sense of them orienting to a ‘good parent,’ rather than talking in terms of being a ‘father’ for many of the SAHDs. This mirrors previous work from Doucet (2006) on Ruddick’s ‘maternal lens.’ While Shirani et al. (2012) suggested in their study of first time fathers, that fathers were somehow insulated against intensive parenting cultures, I would suggest that fathers in a more primary caregiving position, as is the case here, appear to be displaying strong elements of orienting to a good parenting ideology. How this good parenting manifests for this group is in contrast to many of the ‘involved fathering’ studies that still contain the presumption of the mother as the primary caregiver (e.g., Dermott, 2008; Henwood & Proctor, 2003) but also suggests that societal constructions of ‘good fathering’ are out of touch with everyday fathering experiences.

The consideration of stay-at-home fathers within larger discussions of gender, power, and parenting is an important one. These fathers continue to be a minority within contemporary society, a society where it is evident that there are strong societal expectations that mothers undertake the primary-care role, while the fathers are the financial providers with clear discourses around masculinity being tied to this provider status (Haywood & Mac an Ghaill, 2003). While elsewhere we see fathering discourses being bound up with hegemonic masculine ideals (Connell, 1990, 1992; Locke, 2016), contemporary research suggests we are moving toward more sensitive, caring, equal masculinities (Elliot, 2016) of more involved fatherhood (Johansson & Klinth, 2008) with inherently variable masculinities (Coles, 2009). As Elliot (2016) theorizes, caring masculinities reject domination and instead embrace care and relationality. Therefore, she suggests that these “constitute a critical form of men’s engagement and involvement in gender equality and offer the potential of sustained social change for men and gender relations” (page 240).

Therefore, to begin to understand the complexities of gender in relation to modern families, a more thorough examination of the intersection of different factors in relation to parenting, caregiving, and contemporary parenting cultures would be beneficial.

‘Parenting’ in a Pandemic: Mothers, Fathers, and Gendered Norms of Caregiving

As this chapter has demonstrated, gender and parenting are an area full of complexity and nuance. The chapter began by considering advice that is given to gender neutral ‘parents’ before considering the language of the ‘maternal’ and the tensions inherent in the concept and usage of ‘parent’ for gender neutrality. As demonstrated, in much of the advice that is given to new parents, childcare is still commonly seen as predominately women’s work (e.g., Boyer, 2018; Crittenden, 2010). From here the chapter turned to considered gendered constructions of caregiving inherent in contemporary society by focusing on stay-at-home-dads. Here it became apparent that the fathers discussed parenting as being in a ‘partnership’ and this was very much a joint enterprise between both parents. With the rise of fathers in caregiving roles, and also the introduction of Shared Parental Leave (SPL) schemes in many countries, a reconsideration of the language of parenting is perhaps timely. However, since the introduction of SPL in the UK in 2015, the rates of take-up have been consistently low which suggests that while some fathers are wanting to step into a primary caregiving role, this remains an exception rather than a move to a more equal, shared parental responsibility. Reasons for the low take-up have varied but do include workplace and societal norms of gendered caregiving (Locke & Yarwood, 2017; Yarwood & Locke, 2016) as well as fathers’ reluctance to take a career penalty (Working Families, 2020; cf Budig & England, 2001 on ‘motherhood penalty’).

However, a final note for consideration for a chapter on parenting in a volume on gender and power, is the issue of parenting and homeschooling that arose in many parts of the world during the COVID-19 pandemic such as the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 in the UK. In these lockdowns, we saw that the pandemic exacerbated inequalities in gender and parenting (Lyttelton et al., 2023) where across the board, it appeared to be the mothers who were taking on the majority of homeschooling tasks and additional childcare (Petts et al., 2021). This was irrespective of whether they were in relationships and, if so, whether the partners were at home also. Given that many parents were working remotely through most of the pandemic lockdowns in the UK, it is of interest that homeschooling is a task that commonly fell to the (often paid-working) mothers to fulfill. As was reported in the Guardian Newspaper in the UK (8th January 2021) reporting on the closure of schools, the headline was that mothers were taking ‘twice as much unpaid leave as fathers.’ This article drew on a survey carried out in the UK by organizations including the Women’s Budget Group (an independent network of leading academic researchers, policy experts, and campaigners) and the Fawcett Society (a charity which campaigns for gender equality). It claimed that 15% of mothers were said to have taken unpaid leave during earlier lockdowns, in comparison with 8% of fathers. In addition, 57% of fathers said that their jobs did not enable them to work from home during school closures, compared with 49% of mothers. See also O’Reilly (2021) on the gendered impact of parenting in a pandemic. It does appear that the effects of childcare due to the pandemic may have had a more detrimental effect on mothers rather than fathers but, given the focus in this chapter on ‘parenting as partnership,’ the pandemic has held a mirror up to societal discourses and responsibilities of caregiving, despite the move to involved fatherhood and a rise in caregiving fathers. As Yarwood and Locke (2016) noted, in working couples, when a child was ill, it was the norm that mothers took time off to look after the child. They noted that this was the case even where the father worked part-time. The reasons for this seemed to vary and were complex matters of ‘good mothering’ discourses (in line with intensive parenting ideologies) as well as an expectation, in both families and employers, that this was the mother’s role. As Auðardóttir and Rúdólfsdóttir (2021) found in their study in Iceland, parenting in a pandemic is an ‘overwhelming project that requires detailed organization and management.’ This management tended to fall onto the mothers (c.f. Daminger, 2019) rather than being shared equally between parents.

Similarly, with regard to the gendered impact of homeschooling during a pandemic, the gendering of support for homework (and children’s needs) appears to still be societally mandated. As Lehner-Mear (2020) noted, mothers appear to adopt ‘good mothering’ discourses through their maternal support for homework., In essence, performing their (intensive) mothering displays through caregiving and associated practices that are still highly gendered in the expectation of who fulfills these tasks. All of these aspects seem to signify that gendered norms of parenting and caregiving continue to run deeply within many societies despite changes in working practices, societal policies, and other initiatives. The pandemic and the ‘un-doing’ of the steps in gender equality with regard to parenting practices were disappointing to note but also served to remind us of the fragility of cultural change. And, that the introduction of policies relating to sharing parental leave and a societal discourse of ‘involved fatherhood’ are not enough to tackle the complexities of moving toward a new model of parenting that does not differentiate task and responsibility on the basis of gender.

References

Apple, R. D. (1987). Mothers and medicine: A social history of infant feeding, 1890–1950. University of Wisconsin Press.

Arendell, T. (2000). Conceiving and investigating motherhood: The decade’s scholarship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1192–1207.

Auðardóttir, A. M., & Rúdólfsdóttir, A. G. (2021). Chaos ruined the children’s sleep, diet and behaviour: Gendered discourses on family life in pandemic times. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S1), 168–182. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gwao.12519

Ayo, N. (2012). Understanding health promotion in a neoliberal climate and the making of health conscious citizens. Critical Public Health, 22, 99–105.

Badinter, E. (2012). The conflict: How modern motherhood undermines the status of women. Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt & Company.

Baraitser, L., & Spigel, S. (2011). Mapping maternal subjectivities, identities and ethics. In Andrea O'Reilly (Ed.), The 21st century motherhood movement. Demeter Press.

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social Forces, 91(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos120

Boyer, K. (2018). Spaces and politics of motherhood. Rowman and Littlefield International.

Budds, K. (2021). Fit to conceive? Representations of preconception health in the UK press. Feminism & Psychology, 31(4), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520972253

Budds, K., Locke, A., & Burr, V. (2016). “For some people it isn’t a choice, it’s just how it happens”: Accounts of ‘delayed’ motherhood among middle-class women in the UK. Feminism & Psychology, 26(2), 170–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/095935351663961

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657415

Chesley, N. (2011). Stay-at-home fathers and breadwinning mothers: gender, couple dynamics, and social change. Gender & Society, 25(5), 642–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432114174

Children and Families Act. (2014). HMSO.

Christopher, K. (2012). Extensive mothering: Employed mothers’ constructions of the good mother. Gender & Society, 26(1), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243211427700

Coles, T. (2009). Negotiating the field of masculinity: The production and reproduction of multiple dominant masculinities. Men and Masculinities, 12(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X07309502

Connell, R. W. (1990). The state, gender, and sexual politics: Theory and appraisal. Theory and Society, 19(5), 507–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00147025

Connell, R. W. (1992). A very straight gay: Masculinity, homosexual experience, and the dynamics of gender. American Sociological Review, 57(6), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096120

Craig, L. (2006). Does father care mean father share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with their children. Gender and Society, 20(2), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205285212

Crittenden, A. (2010). The price of motherhood: Why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. Picador.

Daminger, A. (2019). The cognitive dimension of household labour. American Sociological Review, 80(1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419859007

Dermott, E. (2008). Intimate fatherhood: A sociological analysis. Routledge.

Dienhart, A. (1998). Reshaping Fatherhood: The social construction of shared parenting. London

Dolan, A. (2014). ‘I’ve learnt what a dad should do’: The interaction of masculine and fathering identities among men who attended a ‘dads only’ parenting programme. Sociology, 48(4), 812–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513511872

Doucet, A. (2006). Do men mother? Fatherhood, care and domestic responsibility. Toronto University Press.

Eerola, J. P., & Huttunen, J. (2011). Metanarrative of the ‘new father’ and narratives of young Finnish first-time fathers. Fathering, 9(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0903.211

Elliot, K. (2016). Caring masculinities: Theorizing an emerging concept. Men and Masculinities, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X1557620

Faircloth, C. (2020). When equal couples become unequal partners: Couple relationships and intensive parenting culture. Families, Relationships and Societies: An International Journal of Research and Debate, 9(§), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674319X15761552010506

Finn, M., & Henwood, K. (2009). Exploring masculinities within men’s identificatory imaginings of first-time fatherhood. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X386099

Foucault, M. (1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordan & P. Miller (Eds.), The foucault effect: Studies in governmentality (pp. 87–104). Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Furedi, F. (2008). Paranoid parenting: Why ignoring the experts may be best for your child. Continuum.

Gillies, V. (2007). Marginalised mothers. Routledge.

Golombok, S. (2015). Modern families. Parents and children in new family forms. Cambridge University Press.

Gorman, K. A., & Fritzsche, B. A. (2002). The good-mother stereotype: Stay at home (or wish that you did!). Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 2190–2201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02069.x

Gross, H., & Pattison, H. (2006). Sanctioning pregnancy. Routledge.

Hauari, H., & Hollingworth, K. (2009). Understanding fathering. Masculinity, diversity and change. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press.

Haywood, C., & Mac an Ghaill, M. (2003). Men and masculinities. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hegewisch, A.,& Gornick, J. (2011). The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: A review of research from OECD countries. Community, Work and Family, 14(2), 126.

Henwood, K., & Procter, J. (2003). The “good father”: Reading men’s accounts of paternal involvement during the transition to first-time fatherhood. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603322438198

Hochschild, A. R., with Machung, A. (1990). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Piatkus.

Johansson, T. (2011). Fatherhood in transition: Paternity leave and changing masculinities. Journal of Family Communication, 11(3), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2011.561137

Johansson, T., & Klinth, R. (2008). Caring fathers: The ideology of gender equality and masculine positions. Men and Masculinities, 11(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06291899

King, L. (2015). Family men. Fatherhood and masculinity in Britain 1914–1960. Oxford University Press.

Kirwin, M. A., & Ettinger, A. K. (2022). Working mothers during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study on mental healthstatus and associations with the receipt of employment benefits. BMC Public Health, 22, 435. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12468-z

Knaak, S. J. (2010). Contextualising risk, constructing choice: Breastfeeding and good mothering in risk society. Health, Risk & Society, 12(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698571003789666

Latshaw, B. A., & Hale, S. I. (2016). ‘The domestic handoff’: Stay-at-home fathers’ time-use in female breadwinner families. Journal of Family Studies, 22(2), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1034157

Lee, E. (2007). Health, morality, and infant feeding: British mothers’ experiences of formula milk use in the early weeks. Sociology of Health & Illness, 29(7), 1075–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01020.x

Lee, E., Bristow, J., Fairloth, C., & Macvarish, J. (2014). Parenting culture studies. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137304612

Lee, E., Macvarish, J., & Bristow, J. (2010). Risk, health and parenting culture (Editorial). Health, Risk & Society, 12, 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698571003789732

Lehner-Mear, R. (2020). Good Mother, Bad Mother?: Maternal identities and cyber-agency in the primary school homework debate. Gender and Education, 33(3), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1763920

Locke, A. (2015). Agency, ‘good motherhood’ and ‘a load of mush’: Constructions of Baby-Led Weaning in the Press. Women’s Studies International Forum (Special Issue on ‘Choosing Motherhood’), 53, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.10.018

Locke, A. (2016). Masculinity, subjectivities and caregiving in the British press: The case of the stay-at-home father. In E. Podnieks (Ed.), Pops in pop culture (pp. 195–212). Palgrave Macmillan.

Locke, A. (2017). Regendering care or undoing gendered binaries of parenting in contemporary UK society? Dialogues in Human Geography, 7(1), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617691

Locke, A. (2023). Putting the ‘teachable moment’ in context. A view from critical health psychology. Journal of Health Psychology, 28(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105322110

Locke, A., & Budds, K. (2013). “We thought if it’s going to take two years then we need to start that now”: Age, probabilistic reasoning and the timing of pregnancy in older first-time mothers. Health, Risk and Society. Special Issue on Time and Risk, 15 (6–7), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2013.827633

Locke, A., & Yarwood, G. (2017). Exploring the depths of gender, parenting and ‘work’: Critical discursive psychology and the ‘missing voices’ of involved fatherhood. Community, Work & Family., 20(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2016.1252722

Lowe, P. K., & Lee, E. J. (2010). Advocating alcohol abstinence to pregnant women: Some observations about British policy. Health, Risk & Society, 12(4), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698571003789690

Lupton, D. (1999). Risk. Routledge.

Lyttelton, T., Zang, E., & Musick, K. (2023). Parents’ work arrangements and gendered time use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Marriage and Family, 85(2), 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12897

Miller, T. (2010). Making sense of fatherhood: Gender, caring and work. Cambridge University Press.

Miller, T. (2011). Making sense of fatherhood: Gender, caring and work. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511778186

Miller, T. (2017). Making sense of parenthood: Caring, gender and family lives. Cambridge University Press.

O’Reilly, A. (2021) “Certainly not an equal-opportunity pandemic”: COVID-19 and Its Impact on Mothers’ Carework, Health, and Employment. In Andrea O’Reilly & Fiona Joy Green (Eds.), Mothers, mothering and Covid-19. Dispatches in a Pandemic (pp. 41–52).

Office for National Statistics. (2016). Employment and labour market. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/economicinactivity

Pailhé, A., Solaz, A., & Stanfors, M. (2021). The great convergence: Gender and unpaid work in Europe and the United States. Population and Development Review, 47(1), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12385

Petts, R. J., Carlson, D. L., & Pepin, J. R. (2021). A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work and Organization, 28(2), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12614

Phipps. A. (2014). The politics of the body: Gender in a neoliberal and conservative age. Polity Press.

Pilcher, J., & Whelehan, I. (2004). Fifty key concepts in gender studies. Sage.

Risman, B. (2009). From doing to undoing: Gender as we know it. Gender & Society, 23(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432083268

Russell, G. (1999). Primary caregiving fathers. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), Parenting and child development in “nontraditional” families (pp. 57–81). Mahwah.

Ruddick, S. (1995). Maternal thinking: Towards a politics of peace. Second Edition. Beacon.

Ryan-Flood, R. (2009). Lesbian Motherhood: Gender. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sayer, L. C. (2005). Gender, time and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work and free time. Social Forces, 84(1), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0126

Shirani, F., Henwood, K., & Coltart, C. (2012). Management and the moral parent meeting the challenges of intensive parenting culture: Gender, Risk. Sociology, 46(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416169

Sullivan, O., Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. P. (2018). Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long- term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12248

Sunderland, J. (2000). Baby entertainer, bumbling assistant and line manager: Discourses of fatherhood in parentcraft texts. Discourse and Society, 11(2), 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926500011002006

Sunderland, J. (2006). “Parenting” or “mothering”? The case of modern childcare magazines. Discourse and Society, 17(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506063126

Thomson, R., Kehily, M. J., Hadfield, L., & Sharpe, S. (2011). Making modern mothers. Policy Press.

Waggoner, M. R. (2017). The zero trimester. University of California Press.

Wall, H. J. (2009). The “Man-Cession” of 2008–09. It’s big, but it’s not great. The Regional Economist, October 2009, 5–9

Wall, G., & Arnold, S. (2007). How involved is involved fathering? An exploration of the contemporary culture of fatherhood. Gender and Society, 21(4), 508–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243207304973

Weston, K. (1991). Families we choose: Lesbians, gays, kinship. Columbia University Press.

Williams, J. C. (2010). Reshaping the work-family debate. Harvard University Press.

Williams, J. C., & Tait, A. (2011). Mancession or “Momcession”?: Good providers, a bad economy, and gender discrimination. 86, Chi_kent. L. Rev. 857 (2011). Available at: http://repository.uschastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/835

Wolf, J. B. (2011). Is breast best? Taking on the breastfeeding experts and the new high stakes of motherhood. New York University Press.

Working Families. (2020). Modern families index full report 2020. Available at: https://workingfamilies.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Modern-Families-Index_2020_Full-Report_FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 1st 2022.

Yarwood, G. A., & Locke, A. (2016). Work, parenting and gender: The care–work negotiations of three couple relationships in the UK. Community, Work and Family, 19(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2015.1047441

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Locke, A. (2023). Parenting as Partnership: Exploring Gender and Caregiving in Discourses of Parenthood. In: Zurbriggen, E.L., Capdevila, R. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41531-9_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41531-9_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-41530-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-41531-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)