Abstract

When discussing ethics and the role of HRD, it is important to distinguish between two different but interrelated aspects. The first aspect, which we call “ethical talent development,” relates to the ethical conduct of HRD professionals, i.e., the need for HRD professionals to act ethically in their talent development work. The HRD Standards on Ethics and Integrity exemplify this aspect. As a code of ethics and an integrity statement, these HRD Standards guide professional practice and the conduct of scholars, consultants, evaluators, and practitioners in the field. The second aspect, which we call “development of ethical talent,” concerns the HRD professionals’ role in fostering individuals’ ethical behavior and building ethical organizations. In this chapter, we introduce these two aspects critical for the HRD profession. We discuss the relevant literature on ethics in HRD to underscore the value of each aspect and propose a framework for a caring HRD practice. We argue for the importance of this approach to ethical issues in furthering HRD scholarship and preparation of HRD professionals. This chapter advances our understanding of ethics in HRD and highlights how HRD professionals could address ethical issues in their work.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

This chapter aims to map and broaden the discussions on ethics in HRD. Prior research in the field has called for more involvement of HRD researchers and practitioners in promoting ethics in organizations (Craft, 2010; Foote & Ruona, 2008; Garavan & McGuire, 2010). As Frisque and Kolb (2008) observed, the current “climate of ethical scandals and wrongdoings poses a significant challenge, and an opportunity, for HRD professionals to positively influence ethical decision-making in organizations” (p. 50). Craft (2010) argued that for companies to become learning organizations, they need ethics programs housed in the HRD area with clear goals and an approach to integrate the program into everyday practices. If HRD desires to truly develop individuals, organizations, and societies, it should deliberately engage in ethical development as one of its main goals. From this perspective, the ethical practice of individuals in their positions should be considered a crucial aspect of their growth. This involves both the ethical development of HRD professionals (i.e., ethical talent development) and the support provided by HRD in the ethical development of other professionals as part of talent development activities (i.e., development of ethical talent).

Talent development is an ambiguous term. Sometimes talent refers to ability or aptitude in a person; other times, it has to do with a talented performance by an individual that “goes beyond the ordinary in meeting some criterion or desirability” (McClelland, 1958, p. 1). Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2013) provided a framework categorizing perspectives on talent in the talent management literature:

-

1.

inclusive vs. exclusive.

-

2.

objective (characteristics) vs. subjective (people as talents).

For this chapter, we adopt an inclusive and subjective definition of talent development as “a comprehensive system that consists of a set of values, activities, and processes with the aim of improving all willing and capable individuals for the mutual benefit of individuals, host organizations, and society as a whole” (Hedayati Mehdiabadi & Li, 2016, p. 287).

According to Hedayati Mehdiabadi and Li (2016), when considering talent as a mixture of innate and realized potentials, HRD’s role is to help individuals identify their innate potentials and develop their skills and knowledge based on their interests. Therefore, talent development and human resource development can be used interchangeably. From this perspective, HRD professionals have an important role in promoting ethical behavior as part of their talent development work to impact the profession, organizations, and society. We discuss two aspects of ethics in the field of HRD in this chapter: ethical talent development and the development of ethical talent. Ethical talent development concerns the ethical practice of HRD professionals, i.e., being ethical in their talent development work. The HRD Standards on Ethics and Integrity exemplify this aspect guiding professional practice and the conduct of scholars, consultants, evaluators, and practitioners. The second aspect, the development of ethical talent, relates to the HRD professionals’ role in improving individuals’ ethical behavior and building ethical organizations. In this chapter, we elaborate on these two critical aspects of the HRD profession.

Ethical Talent Development

In this section, we provide an overview of the HRD profession’s ethical standards and a brief review of some existing work on HRD professional ethics in the field. We then focus on ethics of care as one of the most recently developed ethical theories and argue for its usefulness in the practice and scholarship of HRD. Finally, building on propositions related to ethics of care, we emphasize the need to integrate the efforts on ethical talent development with activities focused on the issues of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Ethical Standards and Codes of Ethics

HRD professionals are tasked with talent development. Like professionals in other fields, HRD practitioners face ethical dilemmas in their daily work and find themselves in situations where they must make ethical decisions. For example, when an HRD practitioner designs a customer service training program and the client rejects the idea of conducting a needs analysis prior to training when such analysis is needed for effective training.

Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider how HRD professionals can make ethical decisions as talent development agents. They can rely on several ethical theories and ethical decision-making frameworks (e.g., utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, and care ethics) in addition to their values and intuitions. HRD scholars and practitioners also have access to the AHRD Standards on Ethics and Integrity (2018) to assure the work they do is aligned with the rules of ethics, integrity, and justice. Using the AHRD Standards on Ethics and Integrity as an example, we can argue that an HRD consultant who suggests training interventions in response to organizational issues, regardless of the underlying problems, does not act ethically. Such an act contrasts with the principle of professional responsibility as one of the general principles stated in the revised AHRD Standards on Ethics and Integrity. According to this principle, “HRD professionals…adapt their methods to the needs of different populations … to serve the best interests of their clients” (AHRD Standards, 2018, p. 5).

The existence of codes of ethics is one of the characteristics that define a profession. The first professional code of ethics in the field of HRD was developed for the Organization Development Institute in 1991 (McLean, 2001). In 1999, the Academy of Human Resource Development introduced its own professional code of ethics and most recently revised it in 2018 (AHRD Standards, 2018). The publications on ethics in the field of HRD have largely focused on ethical talent development and the professional responsibilities of HRD professionals. Below, we briefly highlight some of the key contributions.

In the first issue of the Advances in Developing Human Resources in 2001, several HRD scholars provided case studies on HRD ethics to support HRD practitioners to “serve the needs of their clients [better] and enhance the profession through responsible and ethical behaviors” (Aragon & Hatcher, 2001, p. 5). Russ-Eft (2014), in a book chapter titled “Morality and Ethics in HRD,” reviewed several ethical theories as the basis for ethical decision-making, discussed the role of professional codes of ethics, and provided implications for HRD professionals. Kuchinke (2017) argued that modern work needs deeper engagement with questions of right and wrong and suggested the need for defensible and worthwhile principles for HRD, which should go beyond a list of professional standards. Kuchinke (2017) also called for investigating questions such as “how virtues are and can be enacted in everyday practice, and what boundaries or trade-offs might exist in virtuous action in the context of economic activities” (p. 368). These scholarly works provide a strong foundation for the need for ethical HRD practice and ways in which HRD professionals can engage in ethical decision-making.

In recent years, scholars have argued for the use of ethics of care in the field of HRD (Armitage, 2018; McGuire et al., 2021; Saks, 2021). Recognizing the important contribution of ethics of care to the field, we elaborate on our perspective on the subject and add to the existing knowledge in the field of HRD.

Ethics of Care

Ethics programs in organizations should go beyond teaching ethical standards by helping employees learn how to effectively recognize and respond to ethical problems in the workplace (Sekerka, 2009). To this end, educational tools, ethical frameworks, and theories have been introduced to help individuals navigate their decisions in ethical situations. One of the recent theories of ethical decision-making is ethics of care (or care ethics). Ethics of care, introduced by Carol Gilligan in her book titled, In a Different Voice, has a relational approach to ethical decision-making (Gilligan, 1982). This approach contrasts prior ethical frameworks built on humans’ independent and autonomous image in ethical situations (Held, 2006). Joan Tronto, a leading scholar representing this perspective, discussed that ethics of care “involves both particular acts of caring and a general habit of mind to care that should inform all aspects of a practitioner’s moral life” (2005, p. 252). Ethics of care is built on the following assumptions about human nature: (a) humans are interdependent and therefore not completely autonomous, (b) humans have “needs” in addition to “interest,” and (c) individuals are morally engaged rather than detached (Tronto, 1993). According to Tronto (1993), the need for care does not exist only in a personal context but also in political and social contexts. Care ethics can “expose how the powerful might try to twist an understanding of needs to maintain their positions of power and privilege” (Tronto, 1993, p. 140).

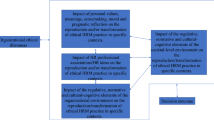

According to Tronto (1993), ethics of care entails the following four components: (a) attentiveness (caring about), (b) responsibility for providing care, (c) competence in caregiving, and (d) responsiveness (caregiving and receiving). We submit that Tronto’s (1993) work provides a foundation and a framework for ethical talent development. Specifically, we propose that a caring HRD practice should embrace all four components, as presented in Fig. 1.

Attentiveness has to do with recognizing the needs of others and thus treating ignorance as an immoral trait (Tronto, 1993). As Tronto (1993) argued, although there exists a tremendous capacity for knowing about others in modern societies, the tendency to focus solely on ourselves and ignore others is prevalent. Ignorance, in this view, will eventually translate into evil with disastrous outcomes for society. Responsibility is the second element of care. For care to happen, one has to accept responsibility for it. As argued by Tronto (1993), responsibility “is embedded in a set of implicit cultural practices, rather than in a set of formal rules or series of promises” (pp. 131–2). The third element, competence, empowers the individual to avoid the bad faith of “taking care of” a problem instead of providing actual care (Tronto, 1993). In other words, to ensure that caring is taking place, the adequacy of competence in providing such care must be considered (Tronto, 1993). Finally, responsiveness has been described as understanding others’ needs through what they express rather than putting oneself into their positions which involves avoiding the presumption “that the other is exactly like the self” (Tronto, 1993, p. 136). Putting oneself in others’ positions “is more likely to be an imposition of an incomplete understanding of the situation than a morally sensitive response” (Tronto, 1993, p. 144). Understanding the actual care needed by different stakeholders who might not share an HRD scholar’s background and identity necessitates building deeper relationships and a sense of openness and humility to learn and adapt.

Caring and feeling empathy for stakeholders is important to the overall success of HRD practice. As suggested by previous researchers, HRD as a field can and should integrate ethics of care into its practices (Armitage, 2018; McGuire et al., 2021; Saks, 2021). Armitage (2018) argued that HRD, for the most part, has adopted a rule-based ethical practice led by a free market value orientation. Instead, the author suggested ethics of care as a possible method for HRD to espouse “the values of human relationships, empathy, dignity, and respect” (Armitage, 2018, p. 212). Further research must be done to identify and examine possible actions to realize such integration. Perhaps the most immediate question is what care means in HRD. As we think about the ethics of care and its integration into the field, we should recognize the challenges of such integration. For example, who gets to decide on the importance of needs and how to balance HRD practitioners’ care for different stakeholders in an organization?

Bridging the HRD Efforts to Address Ethical Issues and Issues of Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

Responding to social injustice is a moral duty grounded in ethical consciousness (Byrd, 2018a). From this perspective, professionals, including HRD researchers and practitioners, have an ethical obligation to challenge social injustice and actively work to make workplaces more inclusive and equitable.

Issues of diversity and the need for inclusion in the workplace have been discussed in the literature in the last few decades. Diversity, as a term, was first popularized with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which identified individuals in the workforce subjected to discriminatory employment practices (Byrd & Sparkman, 2022). However, it was not until the late 1980s that organizations started to recognize the importance of human diversity in the workforce (Byrd, 2018b). Inclusion as a concept was later added to further the discussions and practice of diversity. Inclusion involves “welcoming, respecting, supporting, and valuing the authentic participation of any individual or group” (Perry, 2018, p. 3). More recently, equity and social justice have gained the attention of scholars and practitioners. Equity is related to “the fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement” within the workplace, attempting to eliminate structural barriers that prevent the full participation of marginalized populations (Perry, 2018, p. 4). Rooted in critical theory, Byrd (2018a) suggested the social justice paradigm as “a dedicated platform for studying social justice as a necessary outcome of social injustice” (pp. 3–4).

According to Byrd and Sparkman (2022), the social justice paradigm “creates space for counter-narratives by those who have been subjected to an injustice to challenge the status quo” (p. 79). The social justice case for diversity, where equity and social justice are ends in themselves, can be seen in contrast with the business case for diversity, which emphasizes the value of diversity for business success (Byrd & Sparkman, 2022; Byrd, 2018a). As stated by Byrd and Sparkman (2022),

Whereas competitive advantage and profit maximization are strong influencers for the business case, the social justice case for diversity uses a moral perspective for viewing the lived experiences of socially marginalized groups. Morality and lived experiences of social marginalization are therefore strong influencers for the social justice case. (p. 83)

We argue that ethics of care provides a good framework for connecting ethics and social justice. Caring involves “ethically significant ways in which we matter to each other, transforming interpersonal relatedness into something beyond ontological necessity or brute survival” (Bowden, 1996, p. 1). Ethics of care reminds us of our daily responsibilities to attend to the needs and uniqueness of others and our duties to address social justice issues. We must recognize that as HRD researchers and practitioners, who are in the business of talent development, we might fall into the trap of believing we are more ethical and inclusive by default, due to the nature of the work we do, especially if it concerns the development of ethical talent. However, we suggest we never stop recognizing our privilege and reflect on our day-to-day practices.

In what follows, we outline the second aspect of ethics in HRD: the development of ethical talent.

Development of Ethical Talent

In this section, we start with the need for ethics in organizations and the role HRD professionals can play in developing ethical talent and promoting ethics in the workplace. We then focus on ethics training as one of the integral elements of ethics programs in organizations. Specifically, we elaborate on two orientations to ethics training (i.e., compliance and integrity) and discuss the importance of contextualization in recognizing the different needs of employees for ethics training. Finally, we outline several recommendations for ethics training effectiveness grounded in empirical research. The central messages of the section are that the development of ethical talent is a critical aspect of ethics in HRD, and HRD professionals should play an important role in promoting and fostering ethical behavior in organizations.

From a business perspective, ethics is a must-have for the success of organizations as it plays an essential role in gaining competitive advantage (Watts et al., 2021). Previous research suggests a positive correlation between organizational ethics and measures of corporate success (Chun et al., 2013; Koonmee et al., 2010; Watts et al., 2021). More importantly, from an ethical standpoint, organizations must act ethically, and ethical behavior should be seen as an end in itself, not a means to an end. This perspective, which we argue is in line with a caring HRD, replaces “the profit goal with a goal of responsibility” (Aasland, 2004, p. 4).

Watts et al. (2021) stated that building and maintaining trusting relationships with different stakeholders, such as employees, customers, investors, suppliers, and society, is the essence of business ethics. Human resource development has an important role in developing ethical talent and building ethical culture in organizations (Ardichvili & Jondle, 2009). Ardichvili and Jondle (2009) also advise that creating ethical business culture entails the interaction of individual moral development with situational factors and involves various stakeholders. Such involvement calls for engagement in well-coordinated activities to ensure sustainable results (Ardichvili & Jondle, 2009). Activities such as ethics training at different organizational levels, leadership development, mentoring, and career development are all part of organizational efforts to build an ethical culture. Building an ethical organizational culture by ensuring ethical action by employees is a challenge for training and development professionals (Sekerka, 2009).

Prior research suggests that human resource development has not contributed significantly to promoting ethics (Foote & Ruona, 2008; Tkachenko & Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, 2022). According to Foote and Ruona (2008), a very limited number of studies have focused on business ethics and the role of human resource development. The authors called for the institutionalization of ethical behavior in organizations and argued that human resource development professionals possess specific skills that can be used to promote ethics in organizations (Foote & Ruona, 2008).

Ethics Training: Two Orientations and the Need for Contextualization

Ethics training is one of the integral elements of ethics programs in organizations and, if effective, contributes to developing ethical talent. Ethics training is defined as efforts on the part of an organization to prepare employees to engage in ethical decision-making and moral behavior (Tkachenko & Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, 2022; Watts et al., 2021). Enhancement of ethical decision-making by “identifying and implementing ethical solutions” is the main focus of ethics training programs (Watts et al., 2021, p. 35). Ethics training helps create an ethical culture by not only increasing the skills and knowledge for making ethical decisions but also by conveying the organization’s priorities (Watts et al., 2021). Reviewing two meta-analyses on ethics training programs and their outcomes (i.e., Medeiros et al., 2017, Watts et al., 2017), Watts et al. (2021) concluded that “ethics training programs are more effective when they focus on improving trainee knowledge and skills that directly support ethical decision making …[but] less effective when they focus on changing trainee perceptions of ethical issues” (p. 40).

Scholars recognize that ethics training programs may have two distinct orientations: compliance and integrity (Constantinescu & Kaptein, 2020; Geddes, 2017). Compliance orientation programs aim at reducing “low-road” violations in the workplace and protecting organizations from unethical behavior (Roberts, 2009). In turn, integrity-oriented programs emphasize the importance of values and self-control, sound moral judgment, and building a moral character (Geddes, 2017). Whereas compliance training is increasingly becoming a norm (Perlman et al., 2021), it does not equip employees to handle the full range of ethical issues employees face in organizations (Roberts, 2009). Tkachenko and Hedayati-Mehdiabadi (2022) suggested that, when it comes to addressing ethical issues that are emerging or will happen in the future, integrity ethics training programs are better equipped to prepare employees. Additionally, Kancharla and Dadhich (2021) argued that if ethics training interventions are merely compliance-oriented, opportunities for long-term development will be missed. The challenge and the task of managers and HR professionals is to leverage the synergy of the two orientations by employing their strengths (Tkachenko & Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, 2022).

Another important consideration for ethics training, according to Tkachenko and Hedayati-Mehdiabadi (2022), is the problem of contextualization. Specifically, the authors differentiated between the domain (context) of an organization (workplace) and the domain of a profession (industry). Whereas ethics training that focuses on organizational codes of ethics often addresses the domain of the organization, the nature of the work that professionals perform in an organization may bring unique ethical challenges pertinent to certain professions in the organization (e.g., IT professionals or accountants). Although it is necessary to recognize and communicate ethical guidelines appropriate to all employees in an organization, the authors called for a tailored approach to ethics training by recognizing and addressing the needs of particular professions within the organization to better facilitate the development of ethical talent.

Evidence-Based Recommendations for Ethics Training

Although research into the effectiveness of training and development has been extensive (Bell et al., 2017), what makes ethics training and development effective is less researched (Tkachenko & Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, 2022). To assist HRD practitioners tasked with the design and development of ethics training programs in organizations, we provide several recommendations supported by the existing limited empirical research. To that end, we employ the before-during-after framework building on Benishek and Salas (2014).

Before Training

Scholars underscore the importance of the pre-training stage for the success of ethics training. In addition to conducting a needs analysis, it is necessary to seek commitment and support from all entities involved in ethics training (Packer, 2005). Particularly important is the involvement of the upper leadership, as the leaders’ personal engagement in ethics training can emphasize the importance and priority of the topic to participants (Warner et al., 2011). In addition, according to Barker (1993), it is necessary to recognize the expectations to recognize the expectations of not only executives but also employees and society, as expectations may interplay in a complex way, and the merit and worth of ethics programs may largely depend upon to what extent expectations are met. As Barker (1993) observed, the perceptions of the management and employees on what the ethics program aims to achieve can differ greatly—when management saw it as a business need, employees felt that “it was ‘simply a whitewash scheme to present a false front to (the government)’” (Barker, 1993, p. 172).

During Training

There is growing support for using (inter-) active methods and techniques in ethics training. When developing activities for ethics training, it is recommended to situate them in real-life ethics problems. As observed by Kavathatzopoulos (1994), the use of real-life business ethics problems led to the adoption of a more functional method to address moral problems, compared to when the transfer of moral content happens via lectures. Kaptein (2015) emphasized discussing ethical dilemmas as part of ethics training interventions.

Scholars discussed the effectiveness of case scenarios and realistic vignettes in ethics training (Gaidry & Hoehner, 2016; Izzo et al., 2006). Research has also supported the use of video clips (Warner et al., 2011), graphic novel format (Fischbach, 2015), and simulations (Gallagher et al., 2017) as effective tools for ethics training. Scholars also reported the effectiveness of the so-called “chain teaching” approach, when senior- and middle-level leaders provide guidance on how they expect their subordinates to respond to ethically challenging situations. Such an approach has proved particularly effective in the military context (Warner et al., 2011) and appears promising to be implemented in other contexts.

Researchers underscored the benefits of using reflection (Gallagher et al., 2017) and the use of dialogic exploration of ethics via balanced experiential inquiry (Sekerka et al., 2014). In this reflective technique, individuals use their past experiences to understand what helped and hindered them in responding to ethical situations (Sekerka et al., 2014).

After Training

Researchers emphasize that, while proven effective, an ethics training intervention alone is insufficient to support behavioral change. Organizations need to support trainees to transfer what they have learned. Frisque and Kolb (2008) submitted that “post-training support from supervisors, peers, and the organization is crucial if learned behaviors are to be maintained” (p. 47). It is necessary to continue providing support within a work environment to help employees search for answers on ethics-related issues in the form of ongoing services (e.g., counseling, periodic in-service workshops) to provide the opportunities to extend the support experienced during ethics training interventions (Morgan et al., 2000). As Sekerka et al. (2014) observed, “the importance of providing contexts that incorporate collaborative moral reflection, open dialogue, and shared accountability cannot be overstated” (p. 716). Specifically, providing safe spaces where employees can discuss ethical issues would give employees opportunities to develop moral support in their workplace.

The above section highlighted important considerations pertinent to the second aspect of ethics in HRD, the development of ethical talent. Ethics programs are integral in building ethical organizations. Ethics training, as one of the components of ethics programs, can play a critical role in communicating ethical principles and standards and fostering ethical behavior.

Conclusion

Ethical talent development and development of ethical talent should be seen as two important aspects of HRD practice and ethics-related research in HRD. Recognition of the two aspects would help researchers and practitioners build a better understanding of the contemporary discourse on ethics and its importance in HRD. As ethical issues are gaining attention in the field, clarifying the two aspects is critical. Exposition of ethical talent development and development of ethical talent reduces the confusion about the contributions of HRD scholars on the topic and provides a better picture of the existing efforts within the field and future research directions. In this chapter, we discussed the concept of a caring HRD practice and how it can contribute to organizations and responses of HRD professionals to societal issues. Building on HRD scholars’ work who proposed ethics of care as a promising framework in HRD practice, we underscored the usefulness of ethics of care for connecting ethics and issues of diversity, inclusion, and social justice. In this regard, we submit that ethics of care serves as an important principle for HRD professionals in their daily responsibilities to attend to the needs and uniqueness of others and their duties to address social justice issues. Moving forward, we propose that HRD scholars focus their efforts on how to educate HRD professionals who are ethical and inclusive in their talent development work as well as how to develop ethical talent. Specifically, research into the development of ethical talent should investigate how HRD professionals can facilitate the moral development of individuals and build ethical organizations.

Discussion Questions

-

1.

Discuss the meaning and significance of ethics of care. What are some practical ways in which HRD professionals can engage in ethics of care?

-

2.

What are the challenges for implementing a caring HRD practice in organizations?

-

3.

How can HRD programs prepare HRD professionals to be effective contributors to building ethical organizations?

-

4.

In addition to implementing ethics training, what are other ways to foster the development of ethical talent in organizations?

References

Aasland, D. G. (2004). On the ethics behind “business ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1/2), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039395.63115.c2

Academy of Human Resource Development. (2018). Academy of Human Resource Development Standards on Ethics and Integrity (2nd ed.). www.ahrd.org/resource/resmgr/bylaws/AHRD_Ethics_Standards_(2)-fe.pdf

Aragon, S. R., & Hatcher, T. (Eds.). (2001). Ethics and integrity in HRD: Case studies in research and practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 3(1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/15234220122238166

Ardichvili, A., & Jondle, D. (2009). Ethical business cultures: A literature review and implications for HRD. Human Resource Development Review, 8(2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309334098

Armitage, A. (2018). Is HRD in need of an ethics of care? Human Resource Development International, 21(3), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2017.1366176

Barker, R. A. (1993). An evaluation of the ethics program at General Dynamics. Journal of Business Ethics, 12(3), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01686444

Bell, B. S., Tannenbaum, S. I., Ford, J. K., Noe, R. A., & Kraiger, K. (2017). 100 years of training and development research: What we know and where we should go. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000142

Benishek, L. E., & Salas, E. (2014). Enhancing business ethics: Prescriptions for building better ethics training. In L. E. Sekerka (Ed.), Ethics training in action: An examination of issues, techniques, and development (pp. 3–29). Information Age.

Bowden, P. (1996). Caring: Gender-sensitive ethics. Routledge.

Byrd, M. Y. (2018a). Does HRD have a moral duty to respond to matters of social injustice? Human Resource Development International, 21(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2017.1344419

Byrd, M. Y. (2018b). Re-conceptualizing and re-visioning diversity in the workforce: Toward a social justice paradigm. In M. Y. Byrd & C. L. Scott (Eds.), Diversity in the workforce: Current issues and emerging trends (pp. 307–321). Routledge.

Byrd, M. Y., & Sparkman, T. E. (2022). Reconciling the business case and the social justice case for diversity: A model of human relations. Human Resource Development Review, 21(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843211072356

Chun, J. S., Shin, Y., Choi, J. N., & Kim, M. S. (2013). How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Management, 39(4), 853–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311419662

Constantinescu, M., & Kaptein, M. (2020). Ethics management and ethical management: Mapping criteria and interventions to support responsible management practice. In O. Laasch, R. Suddaby, R. E. Freeman & D. Jamali (Eds.), Research handbook of responsible management (pp. 155–174). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788971966

Craft, J. L. (2010). Making the case for ongoing and interactive organizational ethics training. Human Resource Development International, 13(5), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.520484

Fischbach, S. (2015). Ethical efficacy as a measure of training effectiveness: An application of the graphic novel case method versus traditional written case study. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2118-7

Foote, M. F., & Ruona, W. E. (2008). Institutionalizing ethics: A synthesis of frameworks and the implications for HRD. Human Resource Development Review, 7(3), 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484308321844

Frisque, D. A., & Kolb, J. A. (2008). The effects of an ethics training program on attitude, knowledge, and transfer of training of office professionals: A treatment-and control-group design. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1224

Garavan, T. N., & McGuire, D. (2010). Human resource development and society: Human resource development’s role in embedding corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics in organizations. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 12(5), 487–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422310394757

Gaidry, A. D., & Hoehner, P. J. (2016). Pilot study: The role of predeployment ethics training, professional ethics, and religious values on naval physicians’ ethical decision making. Military Medicine, 181(8), 786–792. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00104

Gallagher, A., Peacock, M., Zasada, M., Coucke, T., Cox, A., & Janssens, N. (2017). Caregivers’ reflections on an ethics education immersive simulation care experience: A series of epiphanous events. Nursing Inquiry, 24(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12174

Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N., & González-Cruz, T. F. (2013). What is the meaning of “talent” in the world of work? Human Resource Management Review, 23, 290–300

Geddes, B. H. (2017). Integrity or compliance based ethics: Which is better for today’s business? Open Journal of Business and Management, 5(3), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2017.53036

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Hedayati Mehdiabadi, A., & Li, J. (2016). Understanding talent development and implications for human resource development: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 15(3), 263–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316655667

Izzo G.M., Langford, B.E., & Vitell, S. (2006). Investigating the efficacy of interactive ethics education: A difference in pedagogical emphasis. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 14(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679140305

Held, V. (2006). The ethics of care: Personal, political, and Global. Oxford University Press.

Kancharla, R., & Dadhich, A. (2021). Perceived ethics training and workplace behavior: The mediating role of perceived ethical culture. European Journal of Training and Development, 45(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-03-2020-0045

Kaptein, M. (2015). The effectiveness of ethics programs: The role of scope, composition, and sequence. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2296-3

Kavathatzopoulos, I. (1994). Training professional managers in decision-making about real life business ethics problems: The acquisition of the autonomous problem-solving skill. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(5), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00871765

Koonmee, K., Singhapakdi, A., Virakul, B., & Lee, D. J. (2010). Ethics institutionalization, quality of work life, and employee job-related outcomes: A survey of human resource managers in Thailand. Journal of Business Research, 63(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.01.006

Kuchinke, K. P. (2017). The ethics of HRD practice. Human Resource Development International, 20(5), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2017.1329369

McClelland, D. C. (1958). Issues in the identification of talent. In D. C. McClelland, A. L. Baldwin, U. Bronfenbrenner & F. R. Strodtbeck (Eds.), Talent and Society: New perspectives in the identification of talent (pp. 1–28). Van Nostrand.

McGuire, D., Germain, M. L., & Reynolds, K. (2021). Reshaping HRD in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: An ethics of care approach. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 23(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422320973426

McLean, G. N. (2001). Ethical dilemmas and the many hats of HRD. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(3), 219. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.10

Medeiros, K. E., Watts, L. L., Mulhearn, T. J., Steele, L. M., Mumford, M. D., & Connelly, S. (2017). What is working, what is not, and what we need to know: A meta-analytic review of business ethics instruction. Journal of Academic Ethics, 15(3), 245–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9281-2

Morgan, B., Morgan, F., Foster, V., & Kolbert, J. (2000). Promoting the moral and conceptual development of law enforcement trainees: A deliberate psychological educational approach. Journal of Moral Education, 29(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240050051765

Packer, S. (2005). The ethical education of ophthalmology residents: An experiment. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society, 103, 240–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.009

Perlman, B. J., Reddick, C. G., Demir, T., & Ogilby, S. M. (2021). What do local governments teach about in ethics training? Compliance versus integrity. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 27(4), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2021.1972742

Perry, R. (2018). Belonging at work: Everyday actions you can take to cultivate an inclusive organization. PYP Academy Press.

Roberts, R. (2009). The rise of compliance-based ethics management: Implications for organizational ethics. Public Integrity, 11(3), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922110305

Russ‐Eft, D. (2014). Morality and ethics in HRD. In N. E. Chalofsky, T. S. Rocco, & M. L. Morris (Eds.), Handbook of human resource development (pp. 510–525). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118839881.ch30

Saks, A. M. (2021). A model of caring in organizations for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 20(3), 289–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843211024035

Sekerka, L. E. (2009). Organizational ethics education and training: A review of best practices and their application. International Journal of Training and Development, 13(2), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2009.00319.x

Sekerka, L. E., Godwin, L. N., & Charnigo, R. (2014). Motivating managers to develop their moral curiosity. Journal of Management Development, 33(7), 709–722. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-03-2013-0039

Tkachenko, O., & Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, A. (2022, July). Employee ethics training: Literature review and integrative perspective. Academy of Management Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2022.17746abstract

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge.

Tronto, J. (2005). An ethic of care. In A. E. Cudd & R. O. Andreasen (Eds.), Feminist theory: A philosophical anthology (pp. 251–263). Blackwell Publishing.

Warner, C. H., Appenzeller, G. N., Mobbs, A., Parker, J. R., Warner, C. M., Grieger, T., & Hoge, C. W. (2011). Effectiveness of battlefield-ethics training during combat deployment: A programme assessment. The Lancet, 378(9794), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61039-8

Watts, L. L., Medeiros, K., McIntosh, T., & Mulhearn, T. (2021). Ethics training for managers: Best practices and techniques. Routledge.

Watts, L. L., Medeiros, K. E., Mulhearn, T. J., Steele, L. M., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2017). Are ethics training programs improving? A meta-analytic review of past and present ethics instruction in the sciences. Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 351–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1182025

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, A., Tkachenko, O., White, L. (2024). Ethics and Human Resource Development: There Are Two Sides to the Coin. In: Russ-Eft, D.F., Alizadeh, A. (eds) Ethics and Human Resource Development. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38727-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38727-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38726-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38727-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)