Abstract

This chapter offers a comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa, with a specific focus on the motives, profiles and strategies of Chinese investors in Zambia and Angola. Drawing on fieldwork and extensive interviews conducted with relevant stakeholders and 50 Chinese companies in Zambia and Angola in 2019, the chapter sheds light on the considerable heterogeneity that exists amongst firms operating in Africa. The chapter goes beyond a surface-level examination by exploring the diverse motivations, including both push and pull factors that drive Chinese investment in these two Southern African countries. By challenging prevailing misconceptions and offering nuanced insights, this chapter contributes to our understanding of the heterogeneous and dynamic nature of Chinese investors in Zambia and Angola. Moreover, it argues that African agency should be also viewed through the lens of policy implementation and the ability to drive fundamental structural change.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: An Overview of Chinese FDI in Zambia and Angola

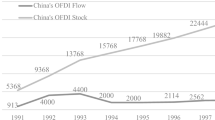

Over the past twenty years, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa has grown exponentially, with FDI stocks increasing almost a one 100-fold from US$ 490 million in 2003 to US$ 43.4 billion in 2020 (Fu 2021). Despite Chinese FDI flows to Africa dropping to US$ 2.7 billion in 2019, they rebounded to US$ 4.2 billion the following year even amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (Fu 2021). Zambia and Angola in particular have been significantly impacted by China’s growing influence in the region (Bastholm and Kragelund 2009; Kopiński and Polus 2011; Kopiński et al. 2011; Lee 2018; de Carvalho et al. 2022) (Fig. 8.1).

The deepening of Zambia’s relationship with China has been marked by, amongst other things, the construction of the Tazara railway, the establishment of an overseas office for the Bank of China in 1997 and the creation of the first African special economic zone (Kragelund 2009; Brautigam and Xiaoyang 2011). Chinese investors have also invested in non-ferrous mines and agricultural projects, with the country consistently being amongst the top ten destinations for Chinese investment in Africa. According to data from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, the stock of Chinese direct investment in Zambia had reached US$ 3.055 billion by the end of 2020 (Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation et al. 2020). Moreover, a 2017 survey estimated the number of Chinese companies in Zambia as being close to 900—aside from Nigeria, this is the largest number on the continent (Sun et al. 2017).Footnote 1

Meanwhile, China’s relationship with Angola has shifted from defence and security to economic development since the end of the latter’s civil war in 2002 (Campos and Vines 2008; Ovadia 2013). Since then, Angola has seen huge numbers of Chinese migrants enter the country, many of been engaged in post-war reconstruction work (Zhuang 2020). According to then Minister for Home Affairs Sebastiao Martins, the number of Chinese in Angola peaked at 259,000 in 2012 (Club-K 2012). Between 2002 and 2008, Angola experienced a ‘golden age’ of post-war growth thanks to the rapidly increasing oil price. In more recent years (especially 2016–2018), however, the global financial crisis and falling oil prices have resulted in many Chinese investors leaving the country. Nevertheless, according to data from the Agency for Private Investment and Promotion of Exports of Angola, China ranked third in FDI to Angola between 2018 and 2022 (China-Lusophone Brief 2022).

Table 8.1 presents key data on Chinese economic engagement with Zambia and Angola. Following this, Fig. 8.2 shows Chinese FDI flows to Angola and Zambia from 2003 to 2021, whilst Fig. 8.3 reveals Chinese FDI stock in Angola and Zambia between 2003 and 2021. Finally, Fig. 8.4 sets out data on trade between China and Angola/Zambia from 1992 to 2021.

Although previous studies on Chinese FDI in Africa provide valuable insights, they are largely based on research conducted nearly a decade ago. Consequently, they fall short in providing a comprehensive picture of the newer Chinese firms established or documenting the changing landscape of Chinese economic engagement with African countries. For instance, in 2012, international media outlets such as the BBC portrayed Nova Cidade de Kilamba, a residential development built by China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC), as a ‘ghost town’ (Redvers 2012). During our research team’s visit to Cidade de Kilamba in 2019, however, we observed that the residential area was fully occupied, despite it still being presented as deserted in academic conferences or discussions. This highlights the importance of conducting updated fieldwork, particularly given Africa’s fast-changing economic environment. As such, this chapter offers a comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation of Chinese FDI in Africa, with specific emphasis on the motives, profiles and strategies of Chinese investors in Zambia and Angola.

Methods

This chapter draws on fieldwork conducted in 2019, when our research team visited and interviewed 50 Chinese companies in Lusaka, Zambia and Luanda, Angola (25 in each country).Footnote 2 This involved participant observation at various Chinese factories, farms and internal conferences, as well as attending dinners, events and other activities organised by Chinese entrepreneurs, Chinese associations or the Chinese embassy in Zambia and Angola. Follow-up interviews with Chinese investors and managers, as well as Zambian and Angolan stakeholders, were conducted in 2020 and 2022 through WeChat, WhatsApp and emails. Tables 8.2 and 8.3 list the interviewed Chinese companies in, respectively, Zambia and Angola.

Profile of Chinese Firms in Zambia and Angola

Private Chinese firms have emerged as a prominent form of Chinese presence in Africa, with Sun et al. (2017) estimating that 90 per cent of Chinese companies are privately owned. This challenges the notion of a monolithic China Inc. operating in Africa. All the private Chinese investors in Zambia and Angola we spoke to noted that the Chinese government—or any other Chinese state actor such as the Chinese embassy—did not interfere with their investment decisions or daily operations. Whilst some Chinese private investors have attempted to establish relations with the Chinese embassy to gain social capital amongst Chinese communities, the majority indicated they did not interact with Chinese state actors. In fact, several private investors expressed frustration at the lack of support available from the Chinese government, policy banks or the Bank of China. These findings challenge the argument put forth by some scholars that Chinese investment in Zambia is state-driven or state-led (Bastholm and Kragelund 2009). Whilst it is certainly incorrect to claim that Chinese economic engagement in these countries is no longer influenced by the Chinese state, it is crucial—as suggested by Lee (2018)—to differentiate the different ‘varieties of capital’ (especially state capital and private capital). Making this differentiation enables better understanding of the dynamics and complexities of Chinese investment in Africa.

There are also other misconceptions about Chinese economic engagement with Africa, often arising from confusion between investment, financing and contracting (Lee 2018; Pairault 2018; Goodfellow and Huang 2021). The difficulty in discerning what counts as overseas development assistance, aid or investment further exacerbates this confusion. Goodfellow and Huang (2021: 659) have emphasised that ‘when it comes to infrastructure, China barely invests at all’. This underscores the fact that many Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), also known as ‘national champions’ in the international contracting industry, primarily focus on engaging in engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts in Africa, as opposed to direct investment in Africa.

Since 2019, both Zambia’s and Angola’s economies have been badly affected by debt distress, leading to a mass exodus of Chinese contracting companies. Chinese investors often face higher exit costs than contracting companies, which is why many agricultural, manufacturing and mining companies have elected to remain. These companies are fundamentally different from contracting companies, as they have come to Zambia for long-term investment purposes rather than short-term ‘projects’ that end once their objectives are met.

As for the profile of Chinese private investors in Angola and Zambia, the majority of their investments are ‘greenfield’. Our research found Chinese–Zambian/Chinese–Angolan joint ventures and acquisitions to be extremely rare. Amongst the 25 Chinese firms we visited in Zambia, only two operated as joint ventures: CNMC Luansha Copper Mines and an emerald producer, which was owned by Chinese (70 per cent) and Indian (30 per cent) partners. In Angola, meanwhile, just one—an agricultural firm—operated as a joint venture. The owners of the Chinese firms offered an array of explanations for this relative dearth of joint enterprises, including lack of trust, unreliability of local partners, a ‘distinctive’ business culture in the host country and a general mismatch between Chinese and local ‘ways of doing things’. Moreover, for the majority of Chinese companies, efficiency was identified as the main operating principle, with many company owners explaining that they prioritise ‘full control of the company’ and ‘do not like to complicate things’.Footnote 3 Local entrepreneurs have often been criticised by the Chinese entrepreneurs for ‘lacking vision and professionalism’, or ‘not being reliable’,Footnote 4 making it ‘impossible’ to run the company together.Footnote 5

The owner of a Lusaka-based manufacturing firm observed: ‘this is not Europe or America. It is difficult to find a local company with the technology, capital and expertise to run a company with. What can a Zambian company offer me? Nothing’.Footnote 6 Another manager lamented that ‘there are a lot of uncertainties if you work with local partners. They don’t deliver on time. They sometimes use our money on other things. Their ability to perform contracts is low’.Footnote 7 A former Chinese journalist in Angola went as far as directly attributing the failure of a joint venture to the local partner:

Angolo-Chi Shopping (海山商贸城) was one of the earliest business and trading centres in Angola and initially attracted large numbers of customers. However, it ultimately failed. Many of us believe it failed because it partnered with Angolan, who are not reliable. So it was doomed.Footnote 8

Motivation: Combination of Push and Pull Factors

Previous studies have explored Chinese companies’ move into Africa (see for example: Biggeri and Sanfilippo 2009; Gu 2009; Chen 2021; Jenkins 2022). This section examines a number of ‘push factors’ (incentives in China that facilitate investment abroad), as well as ‘pull factors’ (incentives in Zambia and Angola that facilitate Chinese investment into their respective countries). These push and pull factors are closely intertwined, something it is important to understand when analysing the current state of Chinese FDI in Zambia and Angola.

Push Factors

Previous research has posited that intense domestic competition and ongoing structural changes in the Chinese economy are the impetus behind Chinese firms deciding to invest in African markets (see for example: Gu 2009, 2011; Shen and Power 2017). In 2014, He Yafei, vice-minister of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, noted that:

The excess capacity has been caused by China’s fundamental economic readjustments against the global economy. With the ensuing knock-on effects of the global financial crisis manifesting in the economic stagnation of advanced nations, coupled with the slowdown in China’s domestic demand, industrial overcapacity, accumulated over several decades, has been brought into sharp relief … [and] has resulted in a steep drop in profits [and] the accumulation of debt and near bankruptcy for many companies. If left unchecked, it could lead to bad loans piling up for banks, harming the ecosystem and bankruptcy for whole sectors of industries that would, in turn, affect the transformation of the [Chinese] growth model and the improvement of people’s livelihoods. It could even destabilise society. The Chinese government, guided by the principles laid out at the third plenum, has put forward guidelines for its resolution. The most important thing is to turn the challenge into an opportunity by ‘moving out’ this overcapacity on the basis of its development strategy abroad and foreign policy.

The Guiding Opinion on Eliminating Severe Excess Capacities, issued by China’s State Council in 2013, highlighted the pressing need to tackle overcapacity, especially in ‘traditional manufacturing industries’ such as cement, steel and flat glass. This crisis of over-production has necessitated new channels for investment, which is now playing out in terms of Chinese FDI in Africa (see Taylor and Zajontz 2020). Overcapacity in China is therefore a major push factor for Chinese companies to invest in Africa, including Zambia and Angola. A case in point is a Lusaka-based cement manufacturing plant, a subsidiary of a Chinese SOE (Sinoma Cement Co., Ltd.), which has an output of 60,000 bags of cement per day. According to the factory’ senior manager, overcapacity in China was the key reason the company turned its attention to Zambia:

Around 2012, we began to face very serious overcapacity in the domestic cement industry. I remember the National Bureau of Statistics of China officially and publicly warned us too much cement was being produced. Our headquarters adjusted our business strategy – we closed some of our cement factories in China and started to focus on expanding foreign market. Zambia was one of the choices.Footnote 9

Fierce competition within China’s domestic market has also been a major driving force behind Chinese investors seeking out opportunities in Africa. For example, Lusaka-based Chinese entrepreneur Mr. Hou observed:

The competition in China is fierce. If I were in China, I could only have an ordinary ‘996 working life’ [a reference to Chinese work culture – work at 9AM, leave at 9PM, work six days a week]. I have no capital and there are not many opportunities for me in the Chinese context. It is different in Zambia. I worked hard for some years for a Chinese company in Zambia, I then borrowed some money and was able to start my own business here.Footnote 10

The vast majority of firms we interviewed in Zambia and Angola stressed the importance of push factors in their decision to internationalise. Even if other considerations propelled them to invest in Africa initially (e.g., market-seeking), push factors keep them there despite the increasingly difficult environment. The companies we interviewed entered the Zambian market during different time periods (ranging from 1990 to 2018). During 1990–2000, the majority of Chinese companies in Zambia were either Chinese SOEs or companies established by earlier groups of diplomats and aid experts who chose to stay after their duties ended. As time has gone on, with the Chinese economy restructuring, push factors have become ever more prominent in China–Africa ties.

This is confirmed by other studies. For instance, Gu notes that Chinese firms are seeking ‘an escape from the pressure cooker of domestic competition and surplus production. China’s private firms find some relief overseas in Africa’s large markets and relatively less intense market competition from local firms’ (Gu 2009: 572). Thus, Chinese firms are pushed to move to Africa by the disadvantages they increasingly face at home, rather than simply being pulled in by market opportunities. In fact, similar to Child and Rodrigues (2005), we argue it is not competitive advantages but competitive disadvantages—in the form of domestic constraints and pressures—that have been driving the recent internationalisation of Chinese firms in Africa. Indeed, many of our interviewees highlighted intense competition within the Chinese market as a driving force behind their decision to invest in Zambia or Angola.

Due to intense competition in China’s domestic market for raw material production, coupled with overcapacity, many Chinese-owned industrial raw material production plants have been established in Africa. During our fieldwork, we identified over ten such plants in Zambia and Angola, which are amongst the largest in the two countries. For example, the state-owned China National Building Material Group has established the Zambia Industrial Park in Zambia, where it operates four production lines capable of producing 2500 tons of clinker cement per day, as well as 200,000 cubic metres of concrete, 700,000 tons of aggregate and 60 million sintered bricks per year (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council 2020). Another noteworthy competitor is the privately owned steel production company, Good Time Steel, which accounts for more than half of Zambia’s steel production. In Angola, we also observed the presence of Chinese steel companies such as Sanyuan Steel.

Another often neglected push factor relates to soft power and is not entirely consistent with market logic. In the agricultural sector, investments made by Chinese SOEs are often part of a mission to improve China’s national image, enhance its soft power and strengthen relationships with African countries (also see: Brautigam 2015; Zhou 2015). African leaders consider agriculture an area of the utmost importance (Wu 2006), which is why we can observe Chinese SOEs participating in agricultural cooperation in Zambia and Angola despite the expected profits failing to materialise. According to the manager of the state-owned China–Zambia Friendship Farm, the farm has no plans to export food to China. Here, the investment made by China is not driven by domestic food demand or the so-called ‘Chinese strategy for food security’, but by China’s desire to maintain a positive image in developing countries. The manager, who indicated the farm had been loss-making from the beginning, stated that:

Agricultural investment (especially in Africa) may not always yield a profitable outcome due to various challenges. Yet, we continue to be active in Zambia. There is historical reason, but the key reason is that our company is a state-owned enterprise. So in this sense, we are distinct from private companies – they only care about profit, but we shoulder social responsibilities and we are the symbol of China–Zambia friendships.Footnote 11

Pull Factors

On the ‘pull’ side, Chinese investors have been drawn by Africa’s abundance of natural resources, the large population size and market potential. Reflecting this, our fieldwork suggests that abundant local resources and growing markets have been important factors pulling Chinese investment into Zambia and Angola.

Previous studies have indicated that the primary motive for Chinese companies entering the African market is gaining access to natural resources. Zambia and Angola, in particular, offer rich resources such as copper, cobalt and oil, making them highly attractive to Chinese investors. Chinese companies have already invested heavily in Zambia’s mining sector, with China Nonferrous Metals Mining Group—purchased through an international bid in 1998—the largest and oldest Chinese-owned mine in the country. By 2017, it had received investments totalling US$ 160 billion to exploit 5 million tons of copper and 120,000 tons of cobalt.

Market potential is also an attractive pull factor. Our fieldwork suggests Chinese investors are attracted by growing consumer demand in Angola and Zambia, as well as their neighbouring countries. Despite being a landlocked country, Zambia adjoins eight other countries, making it an ideal hub for businesses looking to expand their reach in the region. For example, an investor in a mushroom-growing business explained that one of the reasons they had chosen Zambia as a site for the business was its location as an overland hub, which makes it easier to export mushrooms to other countries in the region and beyond.Footnote 12 Angola, meanwhile, boasts a large and rapidly growing market, with Chinese investors indicating that the country’s substantial population of over 25 million people made it an attractive destination. In Luanda, we visited a new energy plant that specialises in producing rechargeable batteries. The factory was experiencing a surge in demand, both domestically and in neighbouring countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, and had plans to ramp up its daily output from 1000 to 4500 units.Footnote 13

A further pull factor is the availability of cheap labour. Our fieldwork revealed that a significant number of Chinese investors opt to invest in the manufacturing sector, with their primary motive for opening factories in Zambia and Angola being the low-cost labour force available in these countries. This has enabled them to manufacture goods at significantly lower costs compared to their home country.

Another pull factor when it comes to Zambia is its stable political environment, with the country recognised as the fourth most peaceful country in Africa, behind only Mauritius, Botswana and Ghana (Lusaka Times 2020). This stability represents a key advantage compared to other countries in the region, such as Angola, where political risks and crime rates are higher.Footnote 14 During our fieldwork in Zambia, we spoke with Mr. An and Mr. Wang, both of whom had previously conducted business in Angola and Nigeria but had since relocated to Zambia. They noted that one of the main reasons for this move was their belief that Zambia was safer and more peaceful than these other countries. The Managing Director of Bank of China in Zambia also attested to the country’s relatively stable political environment and its conduciveness to foreign investors.Footnote 15

In sum, Chinese investment in Zambia and Angola is motivated by both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors, with political and economic conditions in China and the host countries playing a significant role. China’s economic environment—which includes rising wages, intense competition in domestic markets and stricter environmental regulations—as well as the host governments’ policies and resources have all contributed to the above-mentioned factors.

Strategies

Chinese companies operating in Zambia and Angola have over recent years formulated investment strategies that enable them to adapt more effectively to the local business environment. This section highlights some of these essential strategies.

The first strategy is centred around producing products customised to meet local demand. As previously mentioned, market potential is a crucial pull factor drawing Chinese companies to invest in Zambia and Angola. In order to capitalise on localised consumer demand, Chinese investors prioritise localised production when expanding their foothold in the African consumer market. A notable example is provided by Guangde International Group LDA’s subsidiary, Fabrica dos Colchões, in Angola. Fabrica dos Colchões owns the only mattress factory in Angola, with an annual production capacity of 120,000 sheets. According to the CEO, the company’s market share is currently 60 per cent, and it often reaches zero stock due to high demand. Guangde pursued a similar strategy in investing in battery production, catering to both Angola and other countries in Southern Africa. According to its senior manager, these investments were made after thorough market research.

The second strategy employed by various Chinese companies in Zambia and Angola involves tailoring their investment to available local resources. For instance, both African countries possess abundant natural resources that can be utilised in furniture production, including abundant supplies of teak, rosewood, mahogany, ebony, oak and walnut. These can be used to make unique, quality furniture that will appeal to local, regional and international markets. Reflective of this, we discovered during fieldwork that the biggest furniture-making companies in both countries—CNC Furniture Company in Zambia and Yewhing in Angola—are wholly Chinese-owned.

The third strategy involves adaptation, with many of the Chinese companies we interviewed putting in place measures to adjust to the host country’s changing economic circumstances. This is particularly evident in the case of Angola. For example, the initial focus of Lucky Man Angola Developmento—established in Angola in 2003—was infrastructural building. However, since Angola entered a financial crisis in 2015, the group has attempted to transform its development strategy. In 2016, the group identified a 100,000 hectare site for an agricultural project, then, the following year, invested over US$ 28 million to establish Angola’s first fully automated cassava flour processing line. According to the group’s senior manager, the decision to shift focus to agriculture was a strategic move:

We observed that the ‘oil-for-infrastructure’ project can not be a long-term solution. During 2014–2015, we also observed the financial crisis in the country. To better survive in the Angolan market, we realised that we must adapt to the new environment. Our management team then decided to explore other options, and we saw that agriculture had great potential. However, we are aware that in this sector, patience is necessary to turn a profit.Footnote 16

The manager’s explanation resonates with Lee’s (2018) research on Chinese engagement in Zambia’s copper and construction industries. Lee argues that state-owned Chinese firms are characterised by ‘profit optimisation’, which entails satisfying multiple interests simultaneously. These interests include China’s natural resource security and expanding the country’s political influence in Africa, as well as profit-making and market expansion. This is in contrast to global private capital, where ‘profit maximisation’ is typically the sole objective.

Interaction with Local Suppliers

Previous research has identified various reasons potentially contributing to a low level of linkages between foreign investors and local suppliers. These include the poor quality and high costs of local suppliers, scarcity of local products, lack of a local network of specialised suppliers, cultural and language barriers between investors and suppliers and lower capacity and skill levels of host country suppliers (Wang and Zadek 2016; Tang 2019, 2021; Li et al. 2022). Our fieldwork observations and interviews in Zambia and Angola corroborate these findings. For instance, a Chinese investor who had been living in Zambia for two decades and is involved in producing mattresses informed us that she wished to purchase bed covers and a specific type of plastic bag from Zambia. Despite an extensive search, however, she had been unable to locate a local supplier capable of producing these items, forcing her company to import them from China instead.Footnote 17

Previous studies also indicate that investor nationality can significantly influence the extent of linkage formation and spillover effects (Javorcik and Spatareanu 2011; Monastiriotis 2014). Here, our research indicates that, for a number of reasons, Chinese nationality is a crucial factor driving the limited interactions between investors and local firms in Zambia and Angola, indicating the potential for greater spillover effects.

Firstly, the choice of supplier made by Chinese investors is not merely an economic or business decision, but a nuanced choice that takes into consideration guanxi or longer-term benefits, as well as ease of doing business. Many of our interviewees explained that the Chinese community in Zambia and Angola is more or less an ‘acquaintance society’, where Chinese businesspeople know and support each other (Li et al. 2022). Hometown associations, along with other business and commerce associations, reveal the strong diaspora networks present within this ‘acquaintance society’ (Li and Shi 2020). When asked why Chinese suppliers were preferred over local ones (if there was a choice), interviewees would often explain that the Chinese suppliers were their laoxiang (老乡, someone from the same hometown), Chinese friends whom they drink with or recommended by someone influential from a specific hometown association. The consensus amongst many of our Chinese interviewees was that overseas Chinese should ‘take good care of each other and support each other’. As the managing director of a mineral water factory explained: ‘If all the suppliers (be it Zambian, white or Chinese) provide similar price, why don’t we choose a Chinese who we have already known and do them a favour?’.Footnote 18

Secondly, there is a relatively low level of trust between Chinese investors and local suppliers. Knack and Keefer (1997) have discussed the significance of trust in situations where goods and services are exchanged for payment. Many of the Chinese investors with whom we spoke, however, expressed mistrust in local suppliers and/or their products. In Angola, for instance, Chinese investors generally consider products made in Portugal to be of higher quality than those produced locally. Similarly, a manager of an agricultural company revealed he had more faith in chemicals from South Africa or the Netherlands than those made in Zambia. Additionally, several Chinese investors complained that their local suppliers did not deliver products on time.

Thirdly, some Chinese investors prefer Chinese suppliers due to the ease and efficiency of communication, with my previous study highlighting the significance of Chinese digital platforms and communication tools, particularly WeChat groups (Li 2022). This creates an uneven playing field, as local suppliers are excluded from these Chinese migrant/entrepreneur-only groups. Additionally, online enclaves are created amongst Chinese migrants, hindering linkage formation and interactions with local suppliers and wider local society (see Li 2022 and Li et al. 2022).

Finally, some Chinese companies, particularly those operating in multiple sectors, tend towards producing their own materials when they become strong enough. For example, in Zambia, we spoke with an investor whose business involves geo-tech services, project contracting, mining development, international trade and integrated services. In addition, the company is certified Class A in construction, housing and road earthworks by the Zambia Construction Committee. The investor explained that his company is capable of producing diesel oil, stones and other materials, allowing them to produce goods for their own use at significantly lower cost. The investor—also the managing director of the company—explained:

The Chinese value self-reliance, and this principle can be applied to our operations as well. We have experienced significant losses in the past due to the unreliability of some of our local suppliers. Therefore, rather than depending on them, we should strive to rely on our own capabilities. To achieve this, we have taken steps to produce more materials to reduce our dependence on local suppliers.Footnote 19

Discussion and Conclusion

Having implemented a ‘going out’ policy in the early 2000s, numerous Chinese companies invested in Africa, going on to operate across the continent. Despite previous criticism that Chinese firms import labour from China, we found that these companies have become highly localised in Zambia, with over 90 per cent of jobs going to local workers. Moreover, none of the firms we interviewed confirmed the commonly held belief that Chinese firms prefer to hire their own nationals. In fact, we found that Chinese staff rarely exceed 10 per cent of the total workforce, a ratio that has continued to fall over recent years. These findings are consistent with other studies (see Sautman and Hairong 2009; Oya and Schaefer 2019). Many firms have even stated their desire to ‘fire as many Chinese workers as possible and replace them with locals’,Footnote 20 due to salaries for Chinese employees working overseas being much higher than those for local workers. It should be noted, however, that managerial and highly technical positions are still primarily held by Chinese workers. Nevertheless, during our research we did observe that some Chinese companies had made progress in hiring more local staff for these positions.

The investors we interviewed also emphasised their commitment to staying in Africa, for better or worse. Whilst a number of Chinese companies in the construction and trade sector have pulled out of Zambia and Angola in recent years due to their susceptibility to economic fluctuations, most Chinese investors in the agriculture/mining/manufacturing sectors have chosen to remain. Particularly noteworthy is that all the companies we spoke to in the two countries expressed no plans to leave despite worsening economic conditions, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and mounting debt pressures.

Although the profiles, motivations and strategies of Chinese investments in Zambia and Angola bear several similarities, there are also discernible differences. Compared to Zambia, the Chinese business sector in Angola has stronger ‘enclave’ characteristics. The majority of Chinese companies in Angola are located along the highway near Cidade Da China, the biggest Chinese trading centre (referred to by the Chinese as ‘China town’) in Angola. These Chinese companies simultaneously compete and cooperate with each other in the same supply chain—both horizontally and vertically. Selection of the site was also influenced by safety and security concerns in light of Luanda’s high crime rates and social disorder. By contrast, the Chinese business sector in Zambia is more dispersed, with companies operating in various sectors and locations across the country. Whilst there are some clusters, they are not as concentrated as in Angola.

It is important to note that despite the lengthening duration of Chinese investment, there has not been a corresponding increase in linkages with local suppliers (the main focus of this book’s analysis). Chinese companies mostly source basic products or materials from local firms (e.g., wood, stone, clay), which can be characterised as low technology intensity. In many cases, other basic products, such as glue and plastic covers, have to be imported from China, South Africa or Europe. This is not to say that Chinese investments lack potential in terms of generating more positive market spillover effects. In fact, we found that Chinese investments may be able to create new markets for local business. For example, Zambia Sugar Plc, Zambia’s largest sugar manufacturing company, had never sold bagasse (sugarcane pulp) until Chinese firm Jihai Agriculture approached the company.Footnote 21

The outstanding question is whether and how the Zambian and Angolan governments, along with their respective industrial policies, can play a more significant role in promoting linkages and facilitating spillovers. For instance, the Angolan government has established an impressive set of regulations, which includes a local content policy—referred to as ‘Angolanisation’ in the oil industry since 1957. As Teka (2011) and Corkin (2012) note, however, implementation of the policy has failed to achieve its intended objectives. If African economies are to fully reap the benefits of the Chinese presence in the continent, then policy implementation and the ability to create fundamental structural changes—rather than the capacity of state elites to control the negotiating process—should be treated as being at the core of African agency (Kragelund and Carmody 2016; de Carvalho et al. 2022).

Notes

- 1.

According to a Chinese community leader, there are already more than 1000 Chinese companies in Zambia (Che 2020).

- 2.

It should be noted that some of the 50 companies we visited are conglomerates with multiple subsidiary firms. For example, the Luanda-based Guangde Internacional Group LDA has over ten subsidiary companies operating in the construction, trade and manufacturing sectors. In such cases, we only counted Guangde as a single company.

- 3.

Interview with Chinese investors in Lusaka and Luanda, April and May, 2019.

- 4.

Schmitz’s (2021) ethnographic work in Angola echoes this observation, noting a general atmosphere of mistrust between Chinese and Angolan entrepreneurs, with the former repeatedly questioning the reliability of potential collaborators.

- 5.

Interviews with Chinese entrepreneurs in Lusaka and Luanda, April and May, 2019.

- 6.

Interview with a managing director of a Chinese manufacturing firm, Lusaka, 29 April 2019.

- 7.

Interview with a manager of a Chinese mining company, Lusaka, 3 May 2019.

- 8.

Interview with a former Chinese journalist in Angola, WeChat, 30 January 2023.

- 9.

Interview with a manager from Sinoma Cement Co., Ltd., Lusaka, 9 May 2019.

- 10.

Interview with Mr. Hou, Lusaka, 1 May 2019.

- 11.

Interview with the manager of China–Zambia Friendship Farm, Lusaka, 2 May 2019.

- 12.

Interview with Mr. Yao, managing director of Jihai Agriculture Investment and Development Group, Lusaka, 29 April 2019.

- 13.

Interview with a manager, Luanda, May 2019.

- 14.

Chinese in Angola are more concerned about safety and security issues than Chinese in Zambia due to the higher crime rate in Angola (Li 2022).

- 15.

Interview with the managing director of Bank of China Zambia limited, Lusaka, 4 May 2019.

- 16.

Interview with a senior manager, Luanda, 2019.

- 17.

Interview with Ms. Zhai, Lusaka, 2019, 2 May 2019.

- 18.

Interview with Mr. Yu, managing director of Deep Foods Zambia Limited, Lusaka, 5 May 2019.

- 19.

Interview with the (former) managing director of Sinomine International Engineering, 30 April 2019.

- 20.

Interviews with multiple Chinese managers in Zambia and Angola, April and May 2019.

- 21.

According to Mr. Wang, a senior manager of Jihai Agriculture, Zambia Sugar Plc initially refused to sell bagasse as the company as its managers were unsure how much they should sell and what the appropriate price might be. Interview with Jihai’s manager Mr. Wang, Lusaka, 29 April 2019.

References

Bastholm, A. and Kragelund, P. (2009). State-driven Chinese investments in Zambia: Combining strategic interests and profits. In M. P. van Dijk, (ed.), The New Presence of China in Africa: The Importance of Increased Chinese Trade, Aid and Investments for the Sub-Saharan Africa. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Biggeri, M. and Sanfilippo, M. (2009). Understanding China’s move into Africa: An empirical analysis. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 7(1): 31–54.

Brautigam, D. (2015). Will Africa Feed China? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brautigam, D. and Xiaoyang, T. (2011). African Shenzhen: China’s special economic zones in Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 49(1): 27–54.

Campos, I., & Vines, A. (2008). ‘Angola and China’, Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/angola-and-china-pragmatic-partnership.

Child, J., & Rodrigues, S. B. (2005). The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension? 1. Management and Organization Review, 1(3), 381–410.

China-Lusophone Brief. (2022). China among top-3 investors in Angola between 2018 and 2022, 1 June. https://www.clbrief.com/china-among-top-3-investors-in-angola-between-2018-2022/.

Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation, Economic and Commercial Section of the Embassy of the People's Republic of China in Zambia, Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China. (2020). Guide to Foreign Investment and Cooperation Countries (Regions): Zambia. https://fdi.mofcom.gov.cn/resource/pdf/2022/04/07/ff4eddc473d246b1a53945a7aa8a406b.pdf.

Che, J. (2020). Zanbiya huaren shehui saomiao [Scan of Chinese community in Zambia], Qiaowang, 4 September. http://www.qiaowang.org/m/view.php?aid=13693.

Chen, W. (2021). The dynamics of Chinese private outward foreign direct investment in Ethiopia: A comparison of the light manufacturing industry and the construction materials industry, Doctoral dissertation, SOAS University of London.

Club-K. (2012). 25 August. https://www.clubk.net/index.phpoption=com_content&view=article&id=12590:angolarepatriado-37-chineses-porcrimesviolentos&catid=41026:nacional&Itemid=150&lang=pt.

Corkin, L. (2012). Chinese construction companies in Angola: A local linkages perspective. Resources Policy, 37(4): 475–483.

de Carvalho, P., Kopiński, D. and Taylor, I. (2022). A marriage of convenience on the rocks? Revisiting the Sino–Angolan relationship. Africa Spectrum, 57(1): 5–29.

Fu, Y. (2021). The quiet China–Africa revolution: Chinese investment. The Diplomat, 22 November. https://thediplomat.com/2021/11/the-quiet-china-africa-revolution-chinese-investment/.

Goodfellow, T. and Huang, Z. (2021). Contingent infrastructure and the dilution of ‘Chineseness’: Reframing roads and rail in Kampala and Addis Ababa. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(4): 655–674.

Gu, J. (2009). China’s private enterprises in Africa and the implications for African development. The European Journal of Development Research, 21(4): 570–587.

Gu, J. (2011). The last golden land?: Chinese private companies go to Africa. IDS Working Papers, 2011(365): 1–42.

Javorcik, B. S. and Spatareanu, M. (2011). Does it matter where you come from? Vertical spillovers from foreign direct investment and the origin of investors. Journal of Development Economics, 96(1): 126–138.

Jenkins, R. (2022). How China Is Reshaping the Global Economy: Development Impacts in Africa and Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kopiński, D. and Polus, A. (2011) Sino-Zambian relations: ‘An all-weather friendship’ weathering the storm. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(2): 181–192.

Kopiński, D., Polus, A. and Taylor, I. (2011). Contextualising Chinese engagement in Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(2): 129–136.

Kragelund, P. (2009). Part of the disease or part of the cure? Chinese investments in the Zambian mining and construction sectors. The European Journal of Development Research, 21: 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.23.

Kragelund, P. and Carmody, P. (2016) Who is in charge—State power and agency in Sino-African relations. Cornell International Law Journal, 49(1): 1–23.

Knack, S. and Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Lee, C. K. (2018). The specter of global China. In The Specter of Global China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Li, H., Kopiński, D. and Taylor, I. (2022). China and the troubled prospects for Africas economic take-off: Linkage formation and spillover effects in Zambia. Journal of Southern African Studies, 48(5), 861–882.

Li, H. (2022). Global app, local politics and Chinese migrants in Africa: A comparative study of Zambia and Angola. In W. Sun and H. Yu (eds.) WeChat and the Chinese Diaspora. London: Routledge, pp. 234–256.

Li, H. and Shi, X. (2020). Home away from home: The social and political roles of contemporary Chinese associations in Zambia. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 48(2): 148–170.

Lusaka Times. (2020). Zambia ranked the 4th most peaceful African country behind Mauritius, Botswana, and Ghana, 16 June. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2020/06/16/zambia-ranked-the-4th-most-peaceful-country-only-behind-mauritius-botswana-and-ghana-in-africa/.

Monastiriotis, V. (2014). Origin of FDI and domestic productivity spillovers: Does European FDI have a ‘productivity advantage’ in the ENP countries? Europe in Question Discussion Paper Series of the London School of Economics (LEQs) 0, London School of Economics/European Institute.

Ovadia, J. S. (2013) Accumulation with or without dispossession? A ‘both/and’ approach to China in Africa with reference to Angola. Review of African Political Economy, 40(136): 233–250.

Oya, C. and Schaefer, F. (2019). Chinese firms and employment dynamics in Africa: A comparative analysis. IDCEA Synthesis Report.

Pairault, T. (2018). China in Africa: Goods supplier, service provider rather than investor. Bridges Africa, 7(5), 17–22.

Redvers, L. (2012). Angola’s Chinese-built ghost town, 3 July. https://www.bbc.com/news/w.

Sautman, B. and Hairong, Y. (2009). African perspectives on China–Africa links. The China Quarterly, 199: 728–759.

Schmitz, C. M. T. (2021) Making friends, building roads: Chinese entrepreneurship and the search for reliability in Angola. American Anthropologist, 123(2): 343–354.

State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council. (2020). CNBM Holds Open Day Event at Zambia Industrial Park. 28 August. http://en.sasac.gov.cn/2020/08/28/c_5436.htm.

Shen, W. and Power, M. (2017). Africa and the export of China’s clean energy revolution. Third World Quarterly, 38(3), 678–697.

Sun, I. Y., Jayaram, K. and Kassiri, O. (2017). Dance of the lions and dragons: how are Africa and China engaging, and how will the partnership evolve? Mckinsey Report. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/middle%20east%20and%20africa/the%20closest%20look%20yet%20at%20chinese%20economic%20engagement%20in%20africa/dance-of-the-lions-and-dragons.ashx.

Tang, X. (2019). Export, employment, or productivity? Chinese investments in Ethiopia’s leather and leather product sectors. CARI Working Paper 32. Washington, DC: China Africa Research Initiative, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

Tang, X. (2021). Adaptation, innovation, and industrialization: The impact of Chinese investments on skill development in the Zambian and Malawian cotton sectors. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 19(4): 295–313.

Taylor, I. and Zajontz, T. (2020). In a fix: Africa’s place in the Belt and Road Initiative and the reproduction of dependency. South African Journal of International Affairs, 27(3): 277–295.

Teka, Z. (2011). Backward linkages in the manufacturing sector in the oil and gas value chain in Angola. MMCP Discussion Papers (10). http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/256/files/pubs/MMCP%20Paper%2011_0.pdf.

Wang, Y., & Zadek, S. (2016). Sustainability Impacts of Chinese Outward Direct Investment: A Review of the Literature. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/sustainability-impacts-chinese-outward-direct-investment-literature-review.pdf.

Wu, Y. (2006). Excerpts from the Speech by Chinese President Hu Jintao, held at the Nigerian Parliament on 27 April 2006. Sudan Vision Daily, 18 November.

Zhou, J. (2015). Neither ‘Friendship Farm’ or ‘Land Grab’: Chinese Agricultural Engagement in Angola, Policy Brief, No. 07/2015, China Africa Research Initiative (CARI), School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC. http://www.sais-cari.org/publications-policy-briefs.

Zhuang, C. (2020). Angela huaren shehui saomiao [Scan of Chinese Community in Angola), Qiaowang. http://www.52hrtt.com/angela/n/w/info/d1598605501380.

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork of this research was jointly conducted with Dominik Kopiński, Andrzej Polus, Jaroslaw Jura, Paulo de Carvalho and the late professor Ian Taylor. Part of the materials used in this chapter have been published at Journal of Southern African Studies, see Li, H., Kopiński, D., and Taylor, I. (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Li, H. (2023). Chinese Investors in Zambia and Angola: Motives, Profile, Strategies. In: Kopiński, D., Carmody, P., Taylor, I. (eds) The Political Economy of Chinese FDI and Spillover Effects in Africa . International Political Economy Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38715-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38715-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-38714-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-38715-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)