Abstract

Employee voice is a major type of proactive behaviour in the workplace, and its patterns vary across different countries and cultural contexts. In this book chapter, by examining the history and development of employee voice in China, we aim to provide a systematic overview of this line of research in the Chinese context. In specific, this book chapter summarises employee voice research in China regarding the antecedents, outcomes, mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions. To clarify the critical roles of other players within workplace, multiple perspectives (target employee, peers, leaders, etc.) are taken through reviewing previous literature to further understand voice behaviour among Chinese workers and its relevant influences. In addition, this chapter also highlights the typical features and characteristics of employee voice in the Chinese context (i.e., power distance; zhongyong mindset; guanxi, mianzi/face and renqing; collectivism). Future directions for the research are discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The conceptual of voice and its importance have been well established and have a long-standing history in Chinese culture. Just as the Confucian Analects (Lun Yu) says: when walking together with other people, there must be one who can be my teacher. I shall select their good qualities to learn and find out their bad qualities to avoid them. Indeed, from ancient times, Chinese people who have long abided by Confucianism have emphasised the importance of voice such that the emperor specifically appointed bureaucrat officials including Critics (Yan Guan) and Remonstrators (Jian Guan) to make suggestions (Hucker, 1985). A famous example is that the Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty had a blunt and loyal Minister Wei Zheng, and by recognising Wei Zheng’s suggestions and comments, the emperor Taizong once said “without Wei Zheng, I would lose one of my most precious mirrors”. Similarly, the representative of Legalism in ancient China, Han Fei, stated in his book Han Feizi: If you don’t know, but you speak, you are not wise; if you know, but you don’t speak, you are not faithful.

However, in modern business and management, the study of voice behaviour can often be traced back to Western scholar Hirschman (1970), who views voice as a driver to change “the objectionable state of affairs” (p. 30). Specifically, as a typical type of positive and extra-role behaviour, the content of voice behaviour can be either new ideas or ideas to promote organisational efficiency or hidden worries about the current or future of the organisation (Van Dyne et al., 2003). The modern voice research in China has been significantly influenced by existing conceptualisations and literature in Western contexts. Especially, after the critical historical process of the reform and opening (since 1978), business organisations have developed and grown in a social environment with increasing liberty and tolerance, which also occurred in tandem with China’s integration into marketisation and globalisation (Li, 2020). In such a new era, the organisational management in China is intertwined with Western theories and practices, and employee voice behaviour in Chinese organisations has been further highlighted. Many business organisations in China have increased efforts to implement management practices that involve giving employees a chance to express opinions, ideas, concerns and suggestions regarding their jobs (Marchington et al., 2005).

Although China has made remarkable economic and social progress, and business organisations have ushered in a new stage by learning Western modern ideologies and experience in business management, it is impossible to understand the patterns of employee voice in China without considering the unique cultural and historical characteristics. Especially, some scholars have also pointed out the potential influences of traditional Chinese cultural characteristics on voice behaviour. For example, Duan (2011, p. 118) suggests that the concepts of he (i.e. harmony) and zhongyong (i.e. the Doctrine of the Mean) in Confucian culture will lead employees to be “euphemistic and gentle” when expressing their different views. Similarly, Chen and colleagues (2013) tend to regard Chinese cultural features such as renqing (i.e. the obligation to show empathy and repay favours), mianzi (i.e. face), zhongyong, power distance and collectivism as the cultural root of voice behaviour deficiency. Therefore, in this chapter, we expect to explicate the particular features of employee voice in China by reviewing the fruitful extant research outcomes and combining multiple factors embedded in Chinese culture.

Employee Voice Research in China

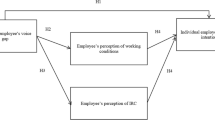

In general, Chinese scholars have derived modern employee voice research from Western research ideology. Meanwhile, various voice studies conducted in China have, in turn, contributed to and enriched the overall literature of employee voice (e.g. Wilkinson et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2015). As depicted in Fig. 5.1, we describe the relationship between modern employee voice research in China and this line of research in Western contexts. Further, we summarise the extant management literature of employee voice in China and elaborate on the contributions of voice research in China on the holistic literature on employee voice.

Conceptualising Voice Behaviour

Employee voice is a well-established concept in management literature, with most research taking place after Hirschman (1970), who expanded the concept of voice to employee level, conceptualising it as a type of behaviour of employees trying to change the potentially adverse situations in the organisation. The voice research has attracted much attention by Chinese management scholars because China has experienced rapid development of science and technology and dramatic changes in the market. Therefore, organisations increasingly need employees to offer advice and suggestions in order to successfully cope with the endless challenges of the business environment (Duan et al., 2016). In line with Hirschman’s (1970) conceptualisation, the research on voice behaviour in China has mainly focused on the level of employees’ voice to the organisation and classified it as a type of behaviour beyond employees’ job tasks (i.e. extra-role performance).

With the advancement of voice literature, organisational scholars have developed various frameworks to broaden our understanding of employee voice behaviour. In terms of contents of voice, while Western researchers tend to agree that there are multiple types of voice (Gorden, 1988; Van Dyne et al., 2003; Van Dyne & LePine, 1998), many of them failed to provide validated measures of those forms of voice (Maynes & Podsakoff, 2013). Given these issues, voice researchers in China have provided additional insights by developing new voice frameworks, expanding the domain of voice and clarifying what elements need to be considered to consist of voice. For example, while Liang et al. (2012) specified that voice can be either promotional to improve organisational performance or prohibitive to hinder organisational development, Wu et al. (2015) drew from role identity theory to propose that voice behaviours are different depending on if the voice behaviours are directly related to the speaker’s job (i.e. self-job-concerned voice and self-job-unconcerned voice). More recently, by recognising that motivation is the key to distinguish different types of voice, Duan et al. (2021) suggest that not all voices are for organisation’s benefit, and thus, employees’ self-serving voice is a new type of voice behaviour worth paying attention to.

Further, employee voice research in China has also highlighted the adoption of different perspectives by examining voice behaviour not only from target employees but also from other key players in the organisation. In particular, considering its object sensitivity feature, voice behaviour can be primarily divided into upward voice (i.e. subordinates to their superiors) and the parallel voice (i.e. voice between employees and colleagues). Yang (2002) points out that, in the context of Chinese culture, the relationship between superior and subordinate is the key to the effective operation of an organisation, and in this sense, the voice behaviours among leaders and subordinates tend to be a major stream of voice research. This is in line with extant literature which demonstrates that various factors such as leader trust (Gao et al., 2011), traditional Chinese leadership (Li & Sun, 2015) and leader-member exchange (Wang et al., 2016) tend to influence employee voice in China. In addition, the roles of colleagues or peers in the focal employee’s engagement in voice behaviour have also attracted scholars’ interests. For example, empirical studies conducted in China suggest that peers’ work performance increases focal employee’s voice behaviour by fostering trust (Zhang & Chen, 2021), and peers’ positive mood is also associated with focal employee’s promotive voice via increased psychological safety (Liu et al., 2015).

Antecedents of Voice Behaviour

The factors contributing to employees’ engagement in voice behaviour are likely to be similar in Western and Chinese contexts. Specifically, existing studies have indicated that Chinese employees’ voice behaviours can be largely influenced by various individual factors such as employee work values (Zhan et al., 2016), psychological capital (Wang et al., 2017), insider identity perception (Li et al., 2017b), perceived voice construction (Cheng, 2020) and perceived excess qualification (Zhou et al., 2020) from different theoretical perspectives such as positive psychological capital and resource conservation theory. In particular, with the rise of indigenous research in China, many voice scholars have focused on investigating the potential role of values and elements derived from Chinese culture, such as zhongyong (Duan & Ling, 2011) and power distance (Chen et al., 2013), which has further enriched the research on employee voice behaviour under the Chinese cultural background. Apart from unique characteristics associated with culture, Chinese scholars have also concentrated on multiple leadership style factors pertaining to Chinese features and their influences on employee voice behaviour. For example, previous research has linked authoritarian leadership (Qiu & Long, 2014), transformational leadership (Duan & Huang, 2014), authentic leadership (Liu & Liao, 2015), humble leader (Zhou & Liao, 2018), self-sacrificial leadership (Yao et al., 2019) and paternalistic leadership (Mao et al., 2020) with Chinese employees’ voice behaviour in the workplace.

Outcomes of Voice Behaviour

Compared with the investigations of causes of voice, the research on outcome variables of voice is relatively less. To consider the potential outcomes of voice behaviour, scholars have focused on two core concepts, from which the results of voice behaviour are studied: voice adoption (i.e. the acceptance and support of leaders for employees’ voice, Zhang et al., 2016) and voice implementation (i.e. implement the voice the leader will adopt, He et al., 2020). While previous research on voice adoption mainly focused on the impact of voice content, voice expression, employees and leaders’ characteristics on voice adoption, another line of research tends to draw from the theory of planned behaviour to reveal the mechanisms to implement the voice by leaders (He et al., 2020).

Moreover, extant research has also focused on employee performance and interpersonal relationships as the outcomes of voice behaviour in Chinese context. For example, Hu et al. (2019) found that employees’ voice behaviour may affect the normal working procedures of the organisation, which causes leaders trouble and thus, results in low performance evaluations on target employees. In contrast, there has been evidence suggesting that voice behaviour can improve leader-member exchange and improve the relationship between superiors and subordinates (Cheng et al., 2013). Further, while Yao (2020) found that voice behaviour is associated with emotional exhaustion and job involvement of the implementers, Liu et al. (2022) indicated that engaging in voice behaviour will not only affect implementers but also affect acts of the bystanders. In addition to various outcomes at the individual level, voice behaviours are likely to generate outcomes at the collective level, especially including the influences on team performance, team innovation and organisational decision-making (Li et al., 2017). This has been supported by Zhang and Liang (2021), who found that voice behaviour is conducive and can integrate different views within the team to predict team effectiveness. Similarly, advocating voice is also likely to be conducive and thus improve organisational innovation (Liang & Tang, 2009).

Contextualising Voice Behaviour to the Chinese Context

Although previous research has revealed various antecedents and outcomes of employee voice behaviour, it is worth noting that cultural characteristics (at least in part) shape the organisational norms for the different voice channels (Kwon & Farndale, 2020). Thus, it is likely that Chinese cultural characteristics and contextual factors activate different mechanisms with respect to understanding of the patterns of employee voice behaviours in China. Indeed, Kwon and Farndale’s (2020) research highlights that national culture affects how people perceive safety and effectiveness during voice, and national cultural factors can either discourage or promote employee voice and signals about the effectiveness consequences of voice. Along the same vein, indigenous research in China also suggests that zhongyong, Guanxi, Mianzi/face and renqing are all key Chinese cultural concepts which influence Chinese employees’ voice behaviour (Zhan & Su, 2019). Therefore, by integrating with Kwon and Farndale’s (2020) framework and extant voice literature focusing on China, we expect to highlight the following aspects to explicate employee voice behaviour in China: power distance, zhongyong mindset, guanxi, mianzi/face, renqing and in-group collectivism. Figure 5.2 depicts how Chinese culture-associated factors may activate underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of employee voice.

Power Distance

Power distance is the degree to which members of an organisation or society assume and agree that power should be stratified and concentrated at a higher level of organisation and government (House et al., 2004). It can be divided into four levels: national, organisational, team and individual. At the national level, the formation of values is usually closely related to the cultural environment in which they are embedded. In China, the Confucian culture of respecting inferiority and superiority and the Legalist culture of being strict but less gracious constitute the fundamental cultural values. A high level of power distance has its cultural root embodied in Chinese Confucian culture such as zun bei you xu (尊卑有序, ordering relationships by status and observing such order) and zhong xiao shun cong (忠孝顺从, loyalty, filial piety and obedience). Considering that the cultural environment can influence employees’ voice behaviour by shaping their power distance tendency (Morrison, 2014), Chinese employees are believed to be more likely to accept centralised leadership and bureaucratic structures and obey orders from leaders. In this sense, they are more sensitive to class hierarchy and less likely to speak up to challenge the status quo. This is supported by Huang et al.’s (2005) research which indicates that Chinese employees tend to have opinion withholding in the workplace because they believe that “silence is golden”, avoid undermining the authority of their superiors or are affected by the implicit “hierarchy concept” abide by the power gap and dare not speak up (p. 461).

At the organisational or group level, power distance has been suggested to particularly affect the communication mode, such that organisations with high-power distance tend to have less feedback from lower-level employees. Indeed, seniority is the epitome of high-power distance within an organisation. Advocation of seniority represents clear hierarchical boundaries among employees, significantly influencing the probability of employees raising objections (Fang, 2015). Supporting this view, Du et al. (2017) reveal that an organisational culture of seniority will inhibit voice behaviour of independent directors, and thus, effective measures should be taken to eliminate the seniority culture that hinders voice, such as eliminating hierarchical ideas and reducing information communication links as far as possible.

At the individual level, power distance tends to be conceptualised as individual cognition which represents the expectation of the subordinate to the leaders’ behaviour in the leader-subordinate dual relationship (Kirkman et al., 2009). The power distance between leaders and employees is an essential factor affecting employees’ voice behaviour such that leaders’ power distance determines whether they are willing to accept voice while employees’ power distance determines whether they dare to voice. Specifically, from the employees’ perspective, power distance orientation will directly affect their choice of communication mode and their role positioning in the whole communication relationship. In this sense, employees with different power distance tendencies are likely to have specific differences in the perception and interpretation of voice behaviour (Hsiung & Tsai, 2017). To explain, employees with high-power distance tendencies have a strong sense of awe and respect for superiors or authority figures. They are more sensitive to the existing hierarchy and authority between communication subjects. Thus, raising objections means breaking tradition, challenging authority and being contrary to their values with a high-power distance tendency. As a result, employees are more inclined to accept top-down orders and instructions rather than question and challenge their superiors (Botero & Van Dyne, 2009). Along the same vein, Zhu and Ouyang (2019) found that, in Chinese context, employees may prefer to know but not speak whether it is promotive voice behaviour that emphasises improvement or prohibitive voice behaviour that emphasises problems. In addition to the direct influence, power distance has also been found to negatively moderate the relationships between various leaderships (e.g. servant leadership, empowering leadership, authentic leadership, conflict management style) and employee voice (e.g. Tan & Liu, 2017; Yu et al., 2015). In contrast, employees with low-power distance orientation are less likely to care about the power and rank difference with their leaders in the upward communication process and thus are more willing to speak up by engaging in voice behaviour (Zhou & Liao, 2018).

From the perspective of leaders, power distance denotes the degree of expectation to which leaders expect employees to recognise formal power relations and comply with and accept their direct influence. Leaders with different levels of power distance have different views on voice behaviour such that high-power distance leaders tend to regard subordinates’ voice behaviour as provocative while low-power distance leaders are likely to see subordinates’ voice behaviour as an expression of responsibility or unique contribution (Han & Liu, 2021). Following this notion, Chinese culture which is characterised with high-power distance tends to foster an authoritative style of leadership (Liao et al., 2010). Such leaders tend to be full of confidence in their own strategic decisions, have a strong desire to control subordinates and regard recommendations as a challenge to their power and credibility (Kirkbride et al., 1991). Therefore, they often ignore and do not adopt the suggestions put forward by their subordinates and even use their power to severely punish employees who hold dissenting opinions.

Zhongyong Mindset

A zhongyong mindset probably is the most typical cultural characteristic of traditional Chinese culture, denoting an ethical and moral philosophy and a way of thinking (Wu & Lin, 2005). Although considered to be a manifestation of Confucianism, zhongyong and its connotations are consistent with the philosophies of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism (Zhou et al., 2019). Especially, being disinclined towards either side is known as zhong (中), and admitting no change is called yong (庸). Given that zhongyong requires one to consider all perspectives, recognise broader conditions and avoid extremes, it has often been viewed in Confucius culture as a noble virtue and even the highest morality. As a practical thinking model of metacognition (Yang, 2009), zhongyong shapes the process of thinking about what action strategies to adopt and how to implement them when dealing with specific events in daily life. In problem-solving, a zhongyong thinker carefully considers things from various angles and acts appropriately (Wu & Lin, 2005).

In Chinese context, zhongyong plays an essential role in affecting individuals through cognitive processes and in shaping business management and organisational practices. Reflecting the Chinese ethical and moral standards, this idea can particularly serve as a guideline for people’s actions and decision-making. Linking zhongyong with employee voice behaviours in the workplace, scholars tend to propose that zhongyong mindset is likely to influence more specific categories of voice rather than employee voice in a general sense (e.g. Chen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017). Supporting this view, Duan and Ling (2011) found that, although zhongyong is unrelated to holistic voice behaviour, it can positively predict overall-oriented voice and negatively predict self-centred voice by employees. Another example is that zhongyong has been approved to be associated positively with promotive voice and negatively with prohibitive voice (Wang & Wang, 2017). The possible explanations are because zhongyong thinkers can control their emotions and consider the feelings of others and potential impacts when making suggestions, which allows them to prioritise harmony when interacting with others and modify their voice based on feedback from others. Such regulating role of zhongyong mindset has also been highlighted in extant literature (e.g. Cai & Geng, 2016). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the relationships between zhongyong and voice also vary depending on the degree of control an individual has over the environment. Zhongyong as a way of thinking depends on the surrounding context, and thus, changes in context can affect the strength of the relationship between zhongyong thinking and subsequent behaviours (Yang & Lin, 2012). According to previous research, while employees’ perception of empowerment moderated the relationship between zhongyong and voice behaviour (Duan & Ling, 2011), zhongyong can also be associated with employees’ cognition on the psychology safety to predict voice behaviour (Yang et al., 2017).

Guanxi, Mianzi/Face and Renqing

Guanxi, mianzi/face and renqing are the critical socio-cultural factors to understand interpersonal interactions and social structure of China (Tsui & Farh, 1997). In China, organisational psychologists suggest that guanxi, mianzi and renqing need to be considered with caution in the process of interpersonal interactions, especially the interactions between leaders, subordinates and colleagues (e.g. Chen et al., 2013). Given that, we expect that those factors are inevitably associated with the patterns of employee voice in China, because too much consideration of such factors tends to inhibit the expression of employees’ voice behaviour. First, in Chinese organisations, the mindset of guanxi allows employees to reciprocate the favours they receive in their social lives. Given that leader-subordinate relationships are the most important interpersonal relationships which can directly influence subordinates’ behaviour (Liang et al., 2019), guanxi is expected to play an essential role in influencing leader—subordinate interactions and associated employee behaviours such as voice. Specifically, unlike the leader-member exchange in Western organisational contexts which are strictly limited to work-related exchanges, the leadership-subordinate relationships in China are strongly “extra-organisational”, and this relationship can penetrate the normal organisational work to play a role within the scope of the organisational system (Law et al., 2000, p. 755). In this sense, close relationships between leaders and subordinates tend to motivate employees to express ideas while poor relationships increase employees’ worry about their words and actions. For example, Wang et al. (2010) found that close guanxi with senior leaders can promote voice behaviour among subordinate managers, possibly due to a sense of reciprocal obligation for subordinate managers to be seen as in-group members, a higher sense of trust in their leaders and the leaders’ tolerance of them, making them relatively less risky to voice. However, under a distant or unfavourable guanxi relationship, leaders are inclined to interpret the subordinate’s voice behaviour as something beyond the work requirements and to cause trouble, which leads to more rejection and aversion to the subordinate’s voice behaviour (Zhou, 2021).

Second, the principle of mianzi, meaning taking care of the social reputation of self, colleagues and leaders and constantly maintaining and enhancing this social reputation (Chen et al., 2013), is also expected to influence employee voice behaviour in China, despite that few researchers have incorporated Chinese mianzi culture into voice behaviour. After all, in Chinese culture, an individual who is good at “being a decent person (会做人)” can be an essential advantage in social interaction. Even if they have different opinions, they prefer private communications and demonstration of face-saving behaviour. Following this notion, under the unique Chinese culture of face consciousness, employees’ voice behaviours, especially those directed at superiors, will be more restrained (Chow et al., 1999). Essentially, employees have been found to be reluctant to voice up because they are afraid of being perceived as questioning the leader’s ability or challenging the leader’s status, which will make the leader lose face and cause damage to interpersonal relations. In line with this, Xia et al. (2016) found that individuals with a weak concept of the principle of face are less likely to sense that their honest speaking would damage the face of and embarrass others, and Liang et al. (2019) found that employees’ face concern mediates the negative relationship between supervisor-subordinate guanxi and employee voice.

Third, we also highlight a potential relationship between renqing and employee voice behaviour in China. Typically, renqing is often associated with the aforementioned guanxi. While guanxi denotes a system of interpersonal exchange and a system of emotional dependence, renqing refers to a form of social capital that could be considered to balance such interpersonal exchanges of services and favours (Chen et al., 2013). When individuals use their relations or networks (i.e. guanxi) to ask a favour, they must repay this favour to restore the balance in relationships (i.e. return renqing). In organisational studies, Huo (2004) pointed out that renqing would make employees avoid conflicts and attach importance to superficial harmony, eventually hindering employees’ prohibitive voice behaviour. Indeed, prohibitive voice behaviour is more challenging and likely to cause dissatisfaction of others, and improper expression is expected to bring the opposite result to the expectation. Therefore, the exchange of renqing among employees will discourage target employees to adopt prohibitive voice behaviour.

Collectivism

Chinese culture is characterised with a high level of collectivism, and people in collectivist cultures tend to put the collective goal first, act according to the collective rules and have relatively consistent behaviour (Chen et al., 2013). In particular, collectivists focus on maintaining relationships, making more situational attributions, avoiding publicity and remaining humble (Triandis, 2001). The effect of collectivism on employees’ voice behaviour in an organisation is complex. On the one hand, as collectivist employees pay attention to collective interests, they tend to propose suggestions and ideas when the organisation faces developmental difficulties and urgently needs reform (Chen et al., 2017). In line with this, Chow et al. (1999) found that middle managers in Taiwan Province of China tend to express views that may be potentially detrimental to themselves but beneficial to the organisation due to their collective sense of responsibility for organisational members. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022) suggest that employees high on collectivism see themselves as a part of the organisation and share their fate and honour with the organisation. Thus, they are more willing to make suggestions for the organisation’s well-being. On the other hand, considering collective interests and harmony, collectivists may also choose to keep silent or engage in voice behaviour that prevents change in order to maintain harmony. Such view is consistent with Wei and Zhang’s research (2010) which reveals that employees’ attention to surface harmony makes them hold negative expectations of the result of voice behaviour, leading to their prohibitive voice behaviour.

Direction for Future Research

As we summarised so far, the voice literature has generated many theoretical and empirical studies investigating employee voice behaviours in China. Based on our aforementioned review, voice studies conducted in Chinese context has enriched the overall voice literature, and there are many questions and areas where we know more than we did several decades ago. However, given the unique characteristics of Chinese culture, we also suggest that several issues should be highlighted for future research to advance our understanding of the patterns of employee voice behaviour in China.

First and foremost, we expect that employee voice scholars may further clarify the conceptualisation and categories of voice behaviour in Chinese context. As we discussed earlier, voice behaviour had been conceptualised as a pro-social and extra-role behaviour which is proactive, change-oriented and improvement-oriented (e.g. Gorden, 1988; Van Dyne et al., 2003; Van Dyne & LePine, 1998). With the advancement of voice literature, Liang et al. (2012) have specified more types of voice behaviours including defensive, acquiescent, promotive and prohibitive voice. More recently, based on data from China, Duan et al. (2021) suggest that voice behaviour can be conceptualised at different foci and emphasise employees’ voice behaviours on issues that are relevant to their own interests (i.e. self-interested voice). The detailed categorisation of voice behaviour is obviously of help to understand employees’ situation-specific psychology and motivation to speak up or not. Therefore, we encourage further research to be conducted to reveal more types of voice behaviours which are essential in Chinese context and can be potentially generalised to other cultural and social settings.

Second, based on our review, we have reconfirmed that context can play an important role in explaining employee voice behaviours. Especially, national culture and related social structure/system can be indicators of context (Wilkinson et al., 2020). In this chapter, we have discussed the potential associations of Chinese cultural characteristics (i.e. power distance, zhongyong mindset, guanxi, mianzi/face, renqing and collectivism) and employee voice behaviour. However, more work needs to be done to clarify the roles of those cultural values in patterns of employee voice behaviour in China. For example, although scholars have highlighted power distance in employee voice research in China (e.g. Brockner et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2020; Song et al., 2019), it can be meaningful to clarify the value congruency between leaders and employees which may be a key proxy for employees’ engagement in voice behaviour. Indeed, Li et al. (2020b) suggest that the more congruent between leaders and subordinates in power distance orientation, the stronger in perceived insider status of subordinates. Since employees are more likely to speak freely with insiders, their perceived insider status should directly determine whether they are willing to speak up and what types of voice they would be engaged into (Li et al., 2020a). Therefore, investigating power distance value congruency can provide a new perspective for scholars to understand employee voice.

Moreover, to increase our understanding of the patterns of employee voice behaviour in China, it is important to consider factors that are correlated with yet distinct from power distance. Typically, traditionality is such a concept, referring to an individual’s cognitive attitudes and behaviours (being characterised with respecting authority, honouring relatives, and ancestors, keeping one’s place, fatalism and male superiority) under the requirements of Chinese traditional culture (Yang et al., 1991). Both power distance and traditionality are rooted in the ethical code of Chinese society. They are essentially interlinked, and power distance tends to be the embodiment of the obeying authority aspect of traditionality in the organisational environment (Chen et al., 2013). However, neither the power distance nor traditionality is conducive to the occurrence of voice in organisations (Chen et al., 2013). Especially, due to its broad conceptualisation, traditionality often does not directly affect voice behaviour (Farh et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, traditionality has been suggested to act as a moderator with an unfavourable effect in voice research. For example, Zhou and Long (2012) found that when the traditionality of employees is high, the positive influence of organisational psychological ownership on voice behaviour becomes weakened. In contrast, Wu and Liu (2014) discovered that employees high on traditionality are likely to be influenced by the value of forgiveness and are inclined to endure grievances to maintain organisational harmony and alleviate the negative impact of bullying behaviour on employees’ prohibitive voice. Therefore, research investigating what role the traditionality can play in motivating or discouraging employee’s voice behaviour in China remains an important area for future research. In addition, we also highlight that future research on employee voice in China could benefit from exploring the role of Chinese cultural value of face or known as mianzi. Although previous research has found that the desire to gain face and maintain the face of others had a significantly and positively predictive effect on employees’ promotive voice behaviour (Chen et al., 2013), it is also possible to posit that maintaining one’s own face has a negative effect on voice behaviour, because individuals may have a concern on and the fear of losing face, which predicts a negative correlation between mianzi and employees’ voice behaviour. Therefore, we suggest that voice behaviour is indeed affected by face, but the conclusion has not been reached. In this sense, future research should examine both positive and negative roles played by mianzi in voice research in China and consider the possible mechanisms which may result in variations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although employee voice literature has been developed for several decades and well established, the research on employee behaviour in China has its own patterns. By reviewing employee voice research under Chinese context, we highlight the importance of contextualising employee voice to the Chinese social structure/system and cultural values, including power distance, zhongyong mindset, guanxi, mianzi/face, renqing and collectivism. Future research, therefore, should make efforts to clarify the potential and essential roles played by those unique cultural and social values in promoting or prohibiting employee voice behaviours in China. Further insight may be gained by combining more of those factors, which should be able to advance our understanding of the complex mechanisms and contingencies of employee voice patterns.

References

Botero, I. C., & Van Dyne, L. (2009). Employee voice behaviour: Interactive effects of LMX and power distance in the United States and Colombia. Management Communication Quarterly, 23(1), 84–104.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M. J., Francesco, A. M., Chen, Z. X., Leung, K., Bierbrauer, G., Gomez, C., Kirkman, B. L., & Shapiro, D. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(4), 300–315.

Cai, X., & Geng, X. (2016). Self-protective implicit voice belief and employee silence: A research in the context of China. Science of Science and Management of S. & T., 37(10), 153–163.

Chen, Q., Fan, Y., Zhang, X., & Yu, W. (2017). Effects of leader information sharing and collectivism on employee voice behaviour. Chinese Journal of Management, 14(10), 1523–1531.

Chen, W., Duan, J., & Tian, X. (2013). Why do not employee voice: A Chinese culture perspective. Advances in Psychological Science, 21(5), 905–913.

Cheng, B. L. (2020). Research on the influence mechanism of personal reputation, perceived voice construction on voice behaviour: The moderating effect of perceived organizational change. Forecasting, 39(5), 68–74.

Cheng, J. W., Lu, K. M., Chang, Y. Y., & Johnstone, S. (2013). Voice behaviour and work engagement: The moderating role of supervisor-attributed motives. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 51(1), 81–102.

Chow, C. W., Harrison, G. L., McKinnon, J. L., & Wu, A. (1999). Cultural influences on informal information sharing in Chinese and Anglo-American organizations: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(7), 561–582.

Du, X., Yin, J., & Lai, S. (2017). Seniority, CEO tenure, and independent directors’ dissenting behaviors. China Industrial Economics, 12, 151–169.

Duan, J. (2011). The research of employee voice in Chinese context: Construct, formation mechanism and effect. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(2), 185–192.

Duan, J., Chen, Z., & Yue, X. (2016). A meta-analysis of the relationship between demographic characteristics and employee voice behaviour. Advances in Psychological Science, 24(10), 1568–1582.

Duan, J., & Huang, C. Y. (2014). The mechanism of individual-focused transformational leadership on employee voice behaviour: A self-determination perspective. Nankai Business Review, 17(4), 98–109.

Duan, J., & Ling, B. (2011). A Chinese indigenous study of the construct of employee voice behavior and the influence of zhong yong on it. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 43(10), 1185–1197.

Duan, J., Xu, Y., Wang, X. T., Wu, C. H., & Wang, Y. (2021). Voice for oneself: Self-interested voice and its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(1), 1–28.

Fang, Z. (2015). Can organizational climate influence employee voice behaviour. Business and Management Journal, 5, 160–170.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729.

Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviours. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 787–798.

Gorden, W. I. (1988). Range of employee voice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 1, 283–299.

Guo, Y., Zhu, Y., & Zhang, L. (2020). Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behaviour: The moderating role of power distance. Current Psychology, 41, 1–10.

Han, Y., & Liu, G. (2021). Why voice channels are stifled? Dimension and formation mechanism of leader voice rejection construct. Human Resources Development of China, 38(4), 111–124.

He, W., Han, Y., Hu, X. F., Liu, W., Yang, B. Y., & Chen, H. Z. (2020). From idea endorsement to idea implementation: A multilevel social network approach toward managerial voice implementation. Human Relations, 73(11), 1563–1582.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hsiung, H. H., & Tsai, W. C. (2017). The joint moderating effects of activated negative moods and group voice climate on the relationship between power distance orientation and employee voice behaviour. Applied Psychology, 66(3), 487–514.

Hu, E. H., Han, M. Y., Shan, H. M., Zhang, L., & Wei, Q. (2019). Does union practice improve employee voice? An analysis from the perspective of planned behaviour theory. Foreign Economics & Management, 41(5), 88–100.

Huang, X., Van de Vliert, E., & Van der Vegt, G. (2005). Breaking the silence culture: Stimulation of participation and employee opinion withholding cross-nationally. Management and Organization Review, 1(3), 459–482.

Hucker, C. O. (1985). A dictionary of official imperial titles in China. Redwood City, CA.

Huo, X. (2004). The Reproduction of Humanity, face, and Power. Sociological Studies, 5, 48–57

Kirkbride, P. S., Tang, S. F., & Westwood, R. I. (1991). Chinese conflict preferences and negotiating behaviour: Cultural and psychological influences. Organization Studies, 12(3), 365–386.

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J. L., Chen, Z. X., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 744–764.

Kwon, B., & Farndale, E. (2020). Employee voice viewed through a cross-cultural lens. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100653.

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., Wang, D., & Wang, L. (2000). Effect of supervisor–subordinate Guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(4), 751–765.

Li, A. N., Liao, H., Tangirala, S., & Firth, B. (2017a). The content of the message matters: The differential effects of promotive and prohibitive team voice on team productivity and safety performance gains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(8), 1259–1270.

Li, C. (2020). Children of the reform and opening-up: China’s new generation and new era of development. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 7(1), 1–22.

Li, S., Luo, J. L., & Liang, F. (2020a). Speaking your mind freely to insiders: The influencing path and boundary of ambidextrous leadership on employee voice. Foreign Economics & Management, 42(6), 99–110.

Li, S., Luo, J. L., & Liang, F. (2020b). The effect of leader-follower value congruence in power distance and perceived insider status on employee voice under the perspective of leader-follower gender combination. Chinese Journal of Management, 17(3), 365–373.

Li, Y., & Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behaviour: A cross-level examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 172–189.

Li, Y. P., Zheng, X. Y., & Liu, Z. H. (2017b). The effect of perceived insider status on employee voice behaviour: A study from the perspective of conservation of resource theory. Chinese Journal of Management, 14(2), 196–204.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & C, & Farh J.L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92.

Liang, J., & Tang, J. (2009). A multi-level study of employee voice: Evidence from a chain of retail stores in China. Nankai Business Review, 12(3), 125–134.

Liang, X., Yu, G., & Fu, B. (2019). How does Supervisor-subordinate Guanxi affect voice? Psychological safety and face concern as dual mediators. Management Review, 31(4), 128–137.

Liao, J. Q., Zhao, J., & Zhang, Y. J. (2010). The influence of power distance on leadership behaviour in China. Chinese Journal of Management, 7(7), 988–992.

Liu, S. M., & Liao, J. Q. (2015). Can authentic leadership really light employee prohibitive voice. Management Review, 27(4), 111–121.

Liu, W., Tangirala, S., Lam, W., Chen, Z., Jia, R. T., & Huang, X. (2015). How and when peers’ positive mood influences employees’ voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 976–989.

Liu, X., Zheng, X., Ni, D., & Harms, P. D. (2022). Employee voice and co-worker support: The roles of employee job demands and co-worker voice expectation. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 43(7), 1171–1286.

Mao, C. G., Fan, J. B., & Liu, B. (2020). The three-way interaction effect of paternalistic leadership on employee voice behaviour. Journal of Capital University of Economics and Business, 22(3), 102–112.

Marchington, M., Rubery, J., & Cooke, F. L. (2005). Prospects for worker voice across organizational boundaries. In Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies (pp. 239–260). Oxford University Press.

Maynes, T. D., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2013). Speaking more broadly: An examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behaviours. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 87–112.

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 1(1), 173–197.

Qiu, G., & Long, L. (2014). The relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ voice: A cross-level analysis. Science Research Management, 35(10), 86–93.

Song, J., Gu, J., Wu, J., & Xu, S. (2019). Differential promotive voice–prohibitive voice relationships with employee performance: Power distance orientation as a moderator. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(4), 1053–1077.

Tan, X., & Liu, B. (2017). Servant leadership, psychological ownership, and voice behaviour in publix sectors: Moderating effect of power distance orientation. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 25(5), 49–58.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of personality, 69(6), 907–924.

Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J. L. L. (1997). Where Guanxi matters: Relational demography and Guanxi in the Chinese context. Work and Occupations, 24(1), 56–79.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviours: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119.

Wang, D., Gan, C., & Wu, C. (2016). LMX and employee voice: A moderated mediation model of psychological empowerment and role clarity. Personnel Review, 45(3), 605–615.

Wang, X., & Wang, P. (2017). The influences of Zhongyong Mindset and Perceived Organizational Support on Employee Voice Behavior. Management and Administration,(9), 50–53.

Wang, L., Huang, J., Chu, X., & Wang, X. (2010). A multilevel study on antecedents of manager voice in Chinese context. Chinese Management Studies, 4(3), 212–230

Wei, X., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Why is there a lack of prohibitive voice in organizations. Journal of Management World, (10), 99–109.

Wilkinson, A., Sun, J. M., & Mowbray, P. K. (2020). Employee voice in the Asia Pacific. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 58(4), 471–484.

Wu, C. H., & Lin, Y. C. (2005). Development of a Zhong-Yong thinking style scale. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 24, 247–300.

Wu, F., & Liu, Lu. (2014). Workplace bullying and voice behavior: Mechanisms of negative emotion and traditionality. Human Resources Development of China, (15), 56–61.

Wu, W., Tang, F., Dong, X., & Liu, C. L. (2015). Different identifications cause different types of voice: A role identity approach to the relations between organizational socialization and voice. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(1), 251–287.

Xia, J., Xu, H., & Ke, T. (2016). Investigation of the Relationship Between the Principle of Face and Preventive Voice. Leadership Science,(14), 38–41.

Yang, G. S., Yu, A.B., & Ye, M. H. (1991). Individual traditionality and modernity of Chinese people: Concepts and measurements. In Chinese psychology and behaviour (Essays). Laurel Books Company.

Yang, M. M. H. (2002). The resilience of guanxi and its new deployments: A critique of some new guanxi scholarship. The China Quarterly, 170, 459–476.

Yang, Y., Jia, L., & Liu, D. (2017). The effect of perceived deep-level dissimilarities on employees’ voice behaviour—The mechanism of perceived emergent states. Business and Management Journal, 39(4), 97–112.

Yang, Z., & Lin, S. (2012). A construct validity study of zhongyong conceptualization. Sociological Studies, 27, 167–186.

Yang, Z. F. (2009). A case of attempt to combine the Chinese traditional culture with the Social Science: The social psychological research of “Zhongyong”. Journal of Renmin University of China, 3(3), 53–60.

Yao, J. (2020). Speaking up as a mixed blessing: A within-individual examination of personal consequences of voice. National University of Singapore.

Yao, N., Zhang, Y., & Zhou, F. (2019). Impact of self-sacrificial leadership on employee voice: A moderated mediation model. Science Research Management, 40(9), 221–230.

Yu, J., Jiang, S., & Zhao, S. (2015). A study on the relationship between conflict management mode and employee voice behaviour—From the perspective of psychological safety and power distance. East China Economic Management, 29(10), 168–174.

Zhan, X., & Su, X. (2019). Research on the impact of personal reputation on voice endorsement: The moderating effect of power distance. Science of Science and Management of S. & T., 40(8), 126–140.

Zhan, X. H., Yang, D. T., & Luan, Z. Z. (2016). The relationship between work values and employee voice behaviour: The moderating effect of perceived organizational support. Chinese Journal of Management, 13(9), 1330–1338.

Zhang, G., & Chen, S. (2021). Effect of peer work performance on the focal employee’s voice taking: The role of trust and self-construal. Psychological Reports, 124(2), 771–791.

Zhang, G. L., Shi, W. T., & Liu, X. W. (2016). A review of researches on the voice taking and future prospects. Human Resources Development of China, 19, 29–37.

Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, C., & Li, F. (2022). Research on the mechanisms of climate for autonomy on employees’ voice behaviour with distinct cultural values. Chinese Journal of Management, 19(1), 36–45.

Zhang, L. M., & Liang, J. (2021). Unpacking the influence of employee voice on team effectiveness—A micro-dynamic perspective. Quarterly. Journal of Management, 6(3), 42–60+183–184.

Zhang, Y., Huai, M. Y., & Xie, Y. H. (2015). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. The leadership quarterly, 26(1), 25–36.

Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., & Cui, L. (2017). Relationship Research between humble leadership and employees’ prohibitive voice. Management Review, 29(5), 110–119.

Zhou, H. (2021). Why do supervisors prefer the voice behaviour of certain subordinates? the effects of guanxi, loyalty, competence, and trust. Management Review, 33(9), 187–197.

Zhou, J., & Liao, J. (2018). Study on the influencing mechanism of humble leader behaviours on employee job performance based on social information processing theory. Chinese Journal of Management, 15(12), 1789–1798.

Zhou, H., & Long, L. R. (2012). The influence of transformational leadership on voice behavior: Mediating effect of psychological ownership for the organization and moderating effect of traditionality. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(3), 388–399.

Zhou, Y., Huang, X., & Xie, W. J. (2020). Does perceived overqualification inspire employee voice? Based on the lens of fairness heuristic. Management Review, 32(12), 192–203.

Zhou, Z., Hu, L., Sun, C., Li, M., Guo, F., & Zhao, Q. (2019). The effect of Zhongyong thinking on remote association thinking: An EEG study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 145–153.

Zhu, Y., & Ouyang, C. (2019). Linking leader empowering behaviour and employee creativity: The influence of voice behaviour and power distance. Industrial Engineering and Management, 24(2), 116–122.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ma, C., Zhang, X., Li, Z. (2023). The Patterns of Employee Voice in China. In: Ajibade Adisa, T., Mordi, C., Oruh, E. (eds) Employee Voice in the Global South. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31127-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31127-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-31126-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-31127-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)