Abstract

The adoption of learning analytics (LA) in higher education institutions in a large scale with the aim of enhancing teaching and learning has many potential benefits but it has one main prerequisite, that is, the ethical uses of LA. Yet, there are many associated ethical issues and challenges identified in the recent research literature. The chapter seeks to contribute to this ongoing discussion on the topic at stake by providing insights from the literature and critically examining them against respective policies or codes of LA ethics at several selected universities in three countries: UK, Canada and Australia. The chapter concludes with a list of recommendations on how to counteract specific challenges that might be inherent to the nature of LA. These conclusions could be useful to universities that are about to create or to change their respective policy or code of LA ethics, as well as to researchers working on the topic.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

11.1 Introduction

Higher education actors have shown an increased interest in deploying Learning Analytics (LA) in their respective institutions, while research continues to shed light on LA benefits. A recent scoping review (Quadri & Shukor, 2021) mentions the most important ones for the higher educational institutions, such as monitoring of students’ dropout and retention, and improving tutors’ performance. LA refers to “the process of measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts” (Siemens, 2012, p. 4). The hidden link between the premises of Quadri and Shukor (2021) and the definition of LA set out by Siemens (2012) is that LA can monitor and predict students’ performance. In turn, this can provide the opportunity for the tutor to identify which students perform poorly in which subject-matter areas. This enables the tutor to obtain a better understanding of the students that are facing problems and thus, to intervene timely; something that could prevent students from failing the course or from dropping out. Yet, student failure (i.e. how it is conceived) and the type of tutor intervention are both context-dependent; for example, in the case of Arnold and Pistilli (2012) LA assisted teachers to provide real-time feedback to students at risk of not reaching their potential. An algorithm using as input a set of context-dependent factors (student performance, effort, academic history, and demographics) determined the risk level for the individual student.

Ferguson and Clow (2017) argue that LA can improve learning practice in higher education institutions (HEI) based on four propositions: (1) they improve learning outcomes, (2) they support learning and teaching, (3) they are deployed widely, and (4) they are used ethically. This chapter revolves around the last aspect focusing on the ethical uses of LA in higher education. A recent systematic review by Viberg et al. (2018) revealed that only 18% of the research studies mention “ethics” or “privacy”. The authors of the review argue that this is a rather small percentage considering that empirical LA research should seriously approach the relevant ethics and they call for a more explicit reflection on the topic. In relation to that, Tsai and Gasevic (2017) mentioned the lack of research work with respect to appropriate LA policies on ethics and privacy as one of the main challenges that hinder LA adoption in higher education.

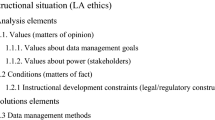

Concerning the scope of this chapter, it considers the ethical uses of LA suggested by the research literature as well as by non-academic sources. In addition, it examines the respective policies at several selected universities in three countries that have a long tradition and presence in the use of LA in higher education: the UK, Canada and Australia. Nine universities were selected based on three criteria: (1) both traditional and distance education universities should be included (seven traditional and two distance education universities), (2) they have public policies written in English that freely accessible online, and (3) they are geographically distributed (three different continents).

The aim of the chapter is to contribute to the ongoing discussion about the topic of ethical issues pertaining to LA use in higher education by providing insight and critical reflections on the different challenges that might interplay and how different policy frameworks address these challenges. In doing that, the chapter focuses on and discusses three common aspects concerning ethical use of LA in higher education: transparency, access, and privacy. The analysis and the discussion focus on these particular aspects as well as on the corrective measures in LA policy frameworks at the selected higher educational institutions to address associated challenges.

11.2 Background

The ethical use of LA in higher education is a multifaceted and complex task. There are many ethical dilemmas associated to it today (Slade & Prinsloo, 2013). Tzimas and Demetriadis (2021) touch upon LA ethics as a field of study by unpacking its concept, but also any contradictory viewpoints emerging among the several stakeholders in a university. Concerning the former, they present LA ethics as a field that addresses moral, legal, and social issues that apply to educational data of any size. Concerning the latter, they present several examples, such as the importance of striking a balance between the availability of student data and limitations imposed on it. Also, the contradiction of using deterministic data-driven algorithms to capture evidence of learning in line with learning theories, which are more complex than behaviorism. Slade and Prinsloo (2013) mention several ethical challenges related to the collection and use of digital student data associated to several processes, such as interpretation, informed consent, privacy, de-identification, and management. Although HEIs have committees with expertise on how to carry out endeavours involving the collection of personal student data or conducting research using such data, LA poses some new conditions. For instance, the ethical issue of equity of treatment, that is, the fact that additional resources and guidance are being directed to just some students (e.g. students at risk of falling out), but not to all of them (Scheffel et al., 2019). Also, one relevant condition involves ensuring data privacy in the case of implementing LA interventions that call for personalised assistance or guidance to the student. Still, a systematic review focusing on the intersection of personalised learning and the use of LA revealed that most studies did not mention how they ensured data privacy or data security (Mavroudi et al., 2018). Adding to that complexity, the new General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) came in effect in 2018 in EU and EU-associated countries and along with that many potential consequences on LA research and practices (Karunaratne, 2021), such as the importance of the possibility for a student to opt-out from a LA endeavour without stating any reason for that.

According to the literature, principles frequently related to LA deployment policies are (Slade & Prinsloo, 2013; Pardo & Siemens, 2014; Steiner et al., 2016): informed consent, privacy, de-identification of data, transparency, student control over data, the possibility of error or bias and associated concerns of LA interpretation, right of access to one’s records of data, accountability, and the right to opt-out. One influential relevant framework that manifests these principles is the code of practice for LA launched by the UK Joint Information Systems Committee in 2015 (JISC, 2015). In addition, the framework mentions the importance of minimizing adverse impacts and enabling positive interventions. Yet, the definitions, interpretations as well as the implications of these principles are still elusive for many. For instance, Prinsloo and Slade (2018) challenge the notion of consent in the digital arena as well as the notion of control over one’s data. Furthermore, it has been suggested that it is almost impossible to define the concept of privacy in the context of LA (Prinsloo & Kaliisa, 2022). Still, there exist context-dependent definitions of the notions of these principles (ibid) in relevant LA policy documents of higher education institutions, or codes of ethics for LA in HEIs. Consequently, in the context of this chapter the main concepts are understood as follows:

-

Transparency is mostly understood in two ways: transparency related to human judgement and transparency related to automated decision-making. The former type pertains to processes that enable stakeholders (and first of all, data subjects that is, individual students) to make informed decisions on LA held about them by providing to them clear and timely information about the parties have access to data, the data collected, and the ways that they visualised (Tzimas & Demetriadis, 2021). The starting point of this type of transparency is transparency of purpose i.e. why will LA benefit the data subjects. The latter type relates to transparency in automated decision-making. Automated decision – making is realised through the processing principles of machine learning and predictive models embedded in LA systems and it is often referred to as algorithmic transparency (Karunaratne, 2021). There is a dialogic relationship between these two types of transparency, which is nicely manifested in the GDPR context. GDRP caters for transparency related to human judgment, but it also secures algorithmic transparency by linking it to the right of the data subjects to know all the related information on “the existence of automated decision-making, including profiling and […] meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing for the data subject.” (GDPR, 2018)

-

Access involves primarily students’ right to access all LA performed on their data in meaningful, accessible formats, and to obtain copies of this data in a portable digital format (JISC, 2015). Students have a legal right under the GDPR to be able to correct inaccurate personal data held about them (JISC, 2015). In more generic terms, this principle requires that the respective LA policy describes the type of operations allowed in the LA dataset and also which users have access to which areas of the LA application (Pardo & Siemens, 2014).

-

Privacy is defined as “the regulation of how personal digital information is being observed by the self or distributed to other observers” (Pardo & Siemens, 2014, p. 438). In the specific context of LA, it involves restricted access to those identified by the institution as having a legitimate need to view the respective LA datasets. If LA are used anonymously, care must be taken by higher education institutions to avoid identification of students from metadata and re-identification by aggregating multiple data sources (JISC, 2015).

11.3 Limitations of LA Mentioned in the Literature

Tsai and Gasevic (2017) identified in the literature six LA challenges related to strategic planning and policy in the context of higher education. The lack of policies that address LA privacy and ethics issues was among them. With respect to ethical issues, their findings indicate that the analyzed policies included relevant considerations of data identification, data access, informed consent, and the possibility to opt out of data collection. Wilson et al. (2017) stresses the difference between capturing students’ activity in some digital environment and capturing evidence of student learning, in effect, the difference between accessing a digital learning resource and meaningfully engaging with it. The authors refer to the former type of analytics as ‘activity analytics’ which act as ‘questionable proxies for learning’ and they outline limitations such as conflicting outcomes from empirical LA studies on predictive analytics. Predictive analytics are LA types which “are used to identify learners who may not complete a course, typically described as being at risk” (Herodotou et al., 2019, p. 1273). Furthermore, the authors mention potentially biased algorithms, the ethics around personalised guidance, and disciplinary differences. Similarly, both Wilson et al. (2017) and Ellis (2013) have raised concerns on the pedagogical meaningfulness of what can be captured via LA. For instance, Ellis (2013) argues that LA is not possible in face-to-face learning sessions that still prevail in higher education institutions because the learning interactions and the learning outcomes cannot be capture in these sessions. Thus, making judgement about student engagement solely from LA evidence sources is not valid. In general, Ellis (2013) posits that LA design and decision-making should be led by pedagogy and not by data. The overall conclusion with respect of LA challenges is that of equating student activity as assessed via LA in a digital learning ecosystem with student engagement. In turn, this conveys the idea that student performance and engagement should not be characterised solely by information on their LA profile.

Furthermore, one of the most crucial barriers of LA adoption in higher education touches upon the presence of biases, either associated to the design of the LA algorithms or to the human judgement and decision-making that stems from using LA – or from both (Uttamchandani & Quick, 2022). In relation to that, several researchers have stressed the need for methods in identifying and dealing with biases in LA (Pelánek, 2020). A recent empirical study examining university students’ attitudes towards LA revealed that the potential of bias was one of the main ethical concerns raised by the students (Roberts et al., 2016). In addition, the recent relevant literature pinpoints to an interesting tension between empowering learners via personalised learning approaches enabled by LA on the one hand while diminishing their agency in the LA lifecycle process on the other hand (Tsai et al., 2020). In other words, how many degrees of freedom do university students have in being actively involved in all the phases of the LA lifecycle? Another relevant and interesting problem that arises is whether the lack of students’ active involvement manifests asymmetrical power relationships between higher education institutions and students (Slade & Tait, 2019). And if so, whether that could inhibit the principles of transparency and access?

Finally, insufficient university staff training and professional development of tutors are frequently mentioned in the literature are barriers of meaningful LA adoption. For instance, Tsai and Gasevic (2017) mention the importance of data literacy skills needed to evaluate the impact and the effectiveness of LA.

11.4 The Central Concepts Manifested in LA Frameworks at the Selected HEIs

The focus of this section is firstly on the ways that the selected LA policy framework integrate the main concepts (transparency, access, privacy) discussed in the previous section. The remaining of this section presents selected points of each framework with respect to these concepts. It also provides secondarily a few relevant comments and interesting points from each framework, for example, about how the respective framework addresses uncertainties/problems with LA.

Interestingly, a few elements are common in all frameworks:

-

A description of how the frameworks facilitate transparency of purpose (transparency)

-

That students have the right to request a copy to see their data (access)

-

The LA privacy policy builds on the generic privacy policy concerning data privacy (privacy).

(These are taken for granted hereafter and thus they not repeated in Sects. 11.4.1, 11.4.2, 11.4.3, 11.4.4, 11.4.5, 11.4.6, 11.4.7, 11.4.8, and 11.4.9). Furthermore, all selected higher education institutions introduce their respective framework of ethical use of LA with a description of how it aligns with core organizational principles and values.

11.4.1 The Open UK

According to the policy of Open UK (2014a, b)

-

the LA privacy policy adheres to a wider university privacy policy which covers topics such as timeframe for retaining personal data, de-identification, and consent

-

algorithmic transparency focuses on statistical models that use standard techniques which can be reviewed and tested

-

students do not have the right to opt-out from LA interventions (in the sense that students cannot ask to exclude data about them)

-

Students can update their personal data.

Other points: Modelling and interventions based on analysis of data should be sound and free from bias; predictive analytics reflect on what has happened in the past to predict the future, thus attention should be placed on calculation of error rates, the acknowledgement of atypical patterns, and guarding against stereotyping.

11.4.2 University of Edinburgh, UK

According to the policy document of the University of Edinburgh (2018).

-

algorithmic transparency is seen a requirement to be assured during procurement of external services

-

students can access and correct any inaccurate personal data held about them.

-

the LA privacy policy adopts the already existing wider data privacy statement which caters for data security and restricting access.

-

access and privacy are examined under the legal basis of legitimate interest.

Other points: it is crucial that the analysis, interpretation and use of the data does not inadvertently reinforce discriminatory attitudes or increase social power differentials; potentially adverse impacts of the analytics and steps taken to remove or minimise them.

11.4.3 University of Glasgow, UK

According to the policy document of the university (n.d.)

-

LA lifecycle processes should be transparent to all stakeholders

-

students have the right to rectification of personal data held about themselves

-

students have the right to opt out

-

the GDPR also raise questions about who has access to data stored in third-party platforms

-

privacy and access are examined under the legal basis of on legitimate interest.

Other points: recognition that LA data does not give a complete picture of a student’s learning; interventions or actions stemming from LA must be inclusive.

11.4.4 Central Queensland University (CQU), Australia

The CQU policy and procedure document (2021) refers to:

-

transparency (which data sources are used, how LA are produced, how students may use LA, and the type of interventions that employees may implement) coupled with student consent

-

de-identification of information kept about students to protect privacy

-

access restricted to those that have a legitimate interest

-

the students’ right to rectification of personal data held about themselves.

Other points: Training and professional development on LA for university staff to minimise the potential for adverse impacts; recognition that LA data does not provide a complete picture of a student.

11.4.5 University of Sydney, Australia

The university has adopted a policy (2016) that caters for:

-

students’ right to access and correct LA data about them

-

students’ right to be notified about privacy breaches and file a formal complain

-

de-identification of (statistical) data and associated privacy concerns

-

transparency of how LA will be collected, used and disclosed.

Other points: regularly reviews of LA processes to ensure relevance with the university goals.

11.4.6 University of Wollongong, Australia

The policy of the university of Wollongong (2017) is characterised by:

-

transparency on data sources, the purposes, the metrics used, different access rights, the boundaries around usage, and data interpretation

-

algorithmic transparency that focuses on how predictive analytics algorithms should be validated, reviewed and improved by qualified staff

-

students’ right to access and correct personal data about them,

-

access rights and restrictions for all stakeholders including external ones

-

not complying with the students’ right to opt-out of inclusion in LA initiatives.

It should be mentioned that the last point is due to the duty of care obligation towards students enacted by monitoring student progress towards learning goals. (The same applies for the case of Open UK, Sect. 11.4.1).

Other points: minimizing adverse impacts, which relates to recognition that LA data does not provide a complete picture of a student and to the fact that opportunities for “gaming the system” are minimised.

11.4.7 Athabasca University, Canada

The Athabasca University in Canada has adopted a comprehensive set of principles for ethical use of personalised student data (2020) which is in line with:

-

transparency on LA lifecycle processes and associated data accuracy controls

-

transparency on data sources and datatypes collected

-

privacy in connection to the “data-minimization” principles.

Other points: consideration of potentially de-motivating effects is required so that LA can help towards supporting and developing student agency; benefit all students (not just at-risk students) in enhancing their academic achievements via LA interventions.

11.4.8 University of British Columbia, Canada

The UCB policy (2019) highlights:

-

students’ agency and their active role as collaborators and co-interpreters of LA (as opposed to just being able to see and access LA or passively receive recommendations)

-

algorithmic transparency especially in the case of predictive analytics algorithms (they should be validated, reviewed and improved by qualified staff)

-

“data minimization” (i.e. accessing only what is necessary) as a means to mitigate the effects of biases.

Other points: acknowledge the possibility of unforeseen consequences and mechanisms for redress; benefit all students (not just at-risk students) in enhancing their academic achievements via LA interventions.

11.4.9 University of Alberta, Canada

The university has adopted a code of ethics (2020) focuses on:

-

algorithmic transparency especially in the case of predictive analytics algorithms (they should be validated, reviewed and improved by qualified staff)

-

informed consent and the possibility to opt-out (privacy self-management)

-

students must be able to access their data and to correct any inaccurate personal data held about them

-

access based on legitimate interest

-

re-identification of data and data anonymization whenever possible.

Other points: inaccuracies in LA data are understood and minimised, and misleading correlations are avoided; the implications of incomplete LA datasets are understood; adverse impacts are minimised i.e. recognition that LA data does not provide a complete picture of a student, opportunities for “gaming the system” are minimised on behalf of the students.

11.5 Discussion and Conclusions

Theoretically, LA holds the promise of promoting the effectiveness of teaching and learning at a large scale in HEIs. There is research work in the LA field providing ample empirical evidence on that. Yet, in practical terms, there are associated ethical challenges that hinder the adoption of LA at a large scale in HE. This state of affairs coupled with the willingness of the research and the educational community to provide solutions to the emerged ethical challenges has motivated the LA research community and the HEIs to work on the ethical concerns: to identify them, and to address them by suggesting proactive and/or corrective measures. The chapter discusses challenges of LA ethics mentioned in the relevant literature as well as by external to the universities organizations, such as JISC that provided one of the leading frameworks in 2015 which still inspires HEIs policies.

The chapter aimed to: (1) identify and define the main theoretical concepts that pertain to the ethical use of LA in HEIs (e.g. transparency, privacy, access), (2) identify and critically discuss principles and limitations associated to these theoretical concepts, and (3) analyse relevant policies in several HEIs coming from three continents (Europe, America, and Australia). The policies adopted by the HEIs included in the review addressed issues that were revolving around the skepticism and the associated ethical challenges of LA deployment mentioned in Sections 11.2 and 11.3. All the main concepts that pertain to ethical issues of LA use in HEIs are tackled in the policies. That does not mean that all policies address equally well all the main issues. This is an expected finding, since the LA policies are fully in line with contextual parameters in HEIs governance such as the vision, the mission, and the core institutional values of the respective HEIs.

All frameworks were characterised by four common elements: (1) a description of how the policy aligns with the principles and values of the respective university, (2) a description of how the framework facilitates transparency of purpose, (3) granting to the students the right to request a copy to see their data, and (4) a description of how the LA privacy policy builds on the wider university policy concerning data privacy. Perhaps then we could consider these core elements as the starting point of an LA policy on ethical uses for higher education institutions.

With respect to transparency, the most basic measure that the HEIs should take is to clarify transparency of purpose by providing proper justifications to all stakeholders on the reasons that lead to embarking into an institution-wide LA analytics endeavour. Besides that, a critical examination of the selected frameworks shows that transparency is understood by its two main aspects: transparency related to human judgement and algorithmic transparency. The former relates to the transparency of communicating all the main processes of LA lifecycle to all the main stakeholders in the most effective way. As a means to encourage this type of transparency, the policies suggest as a good practice effective communication between all the stakeholders involved with the aim of providing information on: the sources and the metrics used, the purpose, different access rights, and data interpretation. The latter relates to the design of LA algorithms. Two main measures are proposed in the examined policies to encourage algorithmic transparency. Firstly, LA algorithms based on standard statistical techniques that can be transparent, tested and audited from the HEIs. This applies especially to predictive LA. Secondly, proposing algorithmic transparency as a procurement requirement for external stakeholders (e.g. learning management system providers). In general, it can be concluded from the above that a holistic framework addresses all the different aspects of transparency that stem from its definition (Tzimas & Demetriadis, 2021). Yet, addressing equally well all these different aspects seems to be a resource-intensive endeavour that calls for expertise that might be difficult and costly to find and recruit internally, especially in a small HEI.

With respect to access, the most interesting finding is its conceptual connection to student agency. What makes this connection the most interesting one, is that (a) it seems to be less apparent than other ideas that one could directly associate to the concept of access, such as one’s right to view the LA dataset about themselves and (b) it was not explicitly discussed in the majority of the frameworks presented herein. A critical analysis of the frameworks presented in Chap. 4 with respect to access concludes on the existence of three levels of in relation to student agency on LA in HEIs:

-

Level 1: students have a right to easily access and see the LA dataset that HEIs keep about them

-

Level 2: students have the right to rectification of (personal) data held about themselves

-

Level 3: students have an active role as collaborators and co-interpreters.

Each level has as prerequisite the previous one. That is, students having an active role as collaborators and co-interpreters presupposes that students have easy access to the LA dataset that HEI keeps of about them (which corresponds to level 1) and that they have the right to correct data in this dataset (which corresponds to level 2). At level 2, one could further distinguish between (sensitive) personal student data and data related to students’ academic achievement. The latter touches upon the question: do the students have the right to change any data related to their academic achievement with which they do not agree? This is a controversial question, especially since it encourages student agency and addresses the asymmetric power relationship between the student and the HEI. At the same time, the majority of the policies recognise (either by stating it directly or by implying it indirectly otherwise) that LA data does not give a complete picture of a student’s learning. This is an important point taking into account that some researchers have expressed skepticism on the power of LA to articulate students’ academic achievement and learning progress – see for example Wilson et al. (2017). Consequently, this chapter is a call for implementing LA policies in HEIs that strive for level 3 with respect to student autonomy. This could favor the idea of using LA as a means to promote honest and constructive dialogue between the tutor and the students on the students’ academic achievement (or on the opposite, on the students’ failure).

Other ensuing recommendations that stem from the recognition that LA data do not provide a complete picture of student’s academic achievement are (1) to think critically on the power of LA to gauge deep learning, (2) to use them complementary with other methods, and (3) to avoid using them as a means of formal student assessment. These recommendations could partially counteract the presence of biases, which is raised in all frameworks presented in Sect. 11.4 and stands out as one of the most important ethical issues on LA in HE. Especially with respect to combatting biases, additional measures suggested by the policies involve continuously assessing the potential of bias in all LA activities and mitigating the effects of biases via “data minimization” e.g. tutors should not have access to students demographics; something that could have a positive impact also on data privacy.

With respect to privacy, in addition to the data minimization technique, the de-identification of data is one of the main measures suggested in the frameworks examined herein. Taking into account that the definition of privacy touches upon access of LA datasets to those identified by the institution as having a legitimate need to view the datasets, it can be concluded that at some extent privacy is inevitably interwoven with access, something that might complicate the study of the frameworks. It is worth noting that some of the universities included in this study did not have in place a comprehensive privacy policy specifically dedicated to LA. Yet, they explicitly stated that the use of LA follows the wider policy of the university on student data (which was quite comprehensive). Something that generates the question whether a dedicated privacy LA policy is actually needed taking into account that the wider privacy policy of the university provides among others recommendations on what constitutes a legitimate need to access and view student data. Yet, student agency could be an answer to what makes a LA privacy policy unique. Similarly, to the concept of access, privacy was ope-rationalised in different levels with respect to student agency in the selected frameworks, ranging from student privacy coupled with access rights and restrictions imposed by the HEIs to privacy self-management on behalf of the students.

Finally, a recommendation that emerges is to promote training of all stakeholders and professional development of tutors to optimise the use of LA in HEIs, something that has been suggested in some of the selected policies. This recommendation could also be viewed as part of a wider and more holistic approach to exploit LA as a means to promote the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in technology-enhanced learning. That can be crucial in the current post-COVID19 digital era. Yet, there is a fine line between tutor’s professional development and tutor’s accountability. Since it emerges that LA do not provide a complete picture of the student and that multiple interpretations of LA can be equally valid, the view of the author is that LA should not be used as a part of an accountability system in HEIs.

This chapter would not have been possible if the universities listed herein had not published their LA policies freely available online. The author joins the voices of Tsai and Gasevic (2017) who encouraged all HEIs to follow that example that promotes opportunities for widening the discussion in the research community and for sustaining the quality of the LA policies in HEIs. Limitations of this work include that it was not clear whether the HEIs selected have more detailed or updated versions of their policies available only for internal usage (Tsai & Gasevic, 2017). Also, that the number of the selected HEIs is rather small and by no means representative of the current situation as a whole. Yet, the purpose of the paper was not to judge how HEIs respond to LA ethical issues as a whole, but to highlight the main challenges described both in the literature and in the selected policies as well as the proposed measures found in the selected policies to address them. The contents of this chapter could be useful to those HEIs that wish to embark in a LA policy, as well as to researchers that study the topic of ethics in LA in HE.

References

Athabasca University. (2020). Principles for ethical use of personalized student data. Available at https://www.athabascau.ca/university-secretariat/_documents/policy/principles-for-ethical-use-personalized-student-data.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Arnold, K. E., & Pistilli, M. D. (2012). Course signals at Purdue: Using learning analytics to increase student success. Second International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference (pp. 267–270). ACM.

Central Queensland University. (2021). Learning analytics policy and procedure. Available at https://www.cqu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/240445/Learning-Analytics-Policy-and-Procedure.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Ellis, C. (2013). Broadening the scope and increasing the usefulness of learning analytics: The case for assessment analytics. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 662–664.

Ferguson, R., & Clow, D. (2017). Where is the evidence? A call to action for learning analytics. Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference (pp. 56–65). ACM.

General Data Protection Regulations – GDPR. (2018). Article 22 automated individual decision-making, including profiling. Available at from https://gdpr-info.eu/art-22-gdpr/. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Herodotou, C., Rienties, B., Boroowa, A., Zdrahal, Z., & Hlosta, M. (2019). A large-scale implementation of predictive learning analytics in higher education: The teachers’ role and perspective. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(5), 1273–1306.

Joint Information Systems Committee – JISC. (2015). Code of practice for learning analytics – JISC. Available at https://www.jisc.ac.uk/sites/default/files/jd0040_code_of_practice_for_learning_analytics_190515_v1.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Karunaratne, T. (2021). For learning analytics to be sustainable under GDPR—Consequences and way forward. Sustainability, 13(20), 11524.

Mavroudi, A., Giannakos, M., & Krogstie, J. (2018). Supporting adaptive learning pathways through the use of learning analytics: Developments, challenges and future opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(2), 206–220.

Open UK. (2014a). Policy on ethical use of student data for learning analytics. Available at https://help.open.ac.uk/documents/policies/ethical-use-of-student-data/files/22/ethical-use-of-student-data-policy.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Open UK. (2014b). Policy on ethical use of student data for learning analytics – FAQs. Available at https://help.open.ac.uk/documents/policies/ethical-use-of-student-data/files/23/ethical-student-data-faq.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Pardo, A., & Siemens, G. (2014). Ethical and privacy principles for learning analytics. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(3), 438–450.

Pelánek, R. (2020). Learning analytics challenges: Trade-offs, methodology, scalability. Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 554–558). ACM.

Prinsloo, P., & Kaliisa, R. (2022). Data privacy on the African continent: Opportunities, challenges and implications for learning analytics. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(4), 894–913.

Prinsloo, P., & Slade, S. (2018). Student consent in learning analytics: The devil in the details? In J. Lester, C. Klein, A. Johri, & H. Rangwala (Eds.), Learning analytics in higher education: Current innovations, future potential, and practical applications (pp. 118–139). Routledge.

Quadri, A. T., & Shukor, N. A. (2021). The benefits of learning analytics to higher education institutions: A scoping review. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16, 23.

Roberts, L. D., Howell, J. A., Seaman, K., & Gibson, D. C. (2016). Student attitudes toward learning analytics in higher education: The fitbit version of the learning world. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1959.

Scheffel, M., Tsai, Y. S., Gašević, D., & Drachsler, H. (2019). Policy matters: Expert recommendations for learning analytics policy. European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning (pp. 510–524). Springer.

Siemens, G. (2012) Learning analytics: Envisioning a research discipline and a domain of practice. Second International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 4–8). ACM.

Slade, S., & Prinsloo, P. (2013). Learning analytics: Ethical issues and dilemmas. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1510–1529.

Slade, S., & Tait, A. (2019). Global guidelines: Ethics in learning analytics (Report). International Council for Open and Distance Education (pp. 2–16).

Steiner, C. M., Kickmeier-Rust, M. D., & Albert, D. (2016). LEA in private: A privacy and data protection framework for a learning analytics toolbox. Journal of Learning Analytics, 3(1), 66–90.

Tsai, Y. S., & Gasevic, D. (2017) Learning analytics in higher education—challenges and policies: A review of eight learning analytics policies. Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference (pp. 233–242). ACM.

Tsai, Y. S., Perrotta, C., & Gašević, D. (2020). Empowering learners with personalised learning approaches? Agency, equity and transparency in the context of learning analytics. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 554–567.

Tzimas, D., & Demetriadis, S. (2021). Ethical issues in learning analytics: A review of the field. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 1101–1133.

University of Alberta. (2020). Code of practice for learning analytics at the UofA. Available at https://policiesonline.ualberta.ca/PoliciesProcedures/InfoDocs/@academic/documents/infodoc/UofA%20Code%20of%20Practice%20for%20Learning%20Analytics.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

University of British Columbia. (2019). Learning analytics at UBC: purpose and principles. Available at https://ctlt-learninganalytics.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2019/07/Learning-Analytics-Purpose-and-Principles.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

University of Edinburgh. (2018). Policy and procedures for developing and managing Learning Analytics activities. Available at https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/learninganalyticspolicy.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

University of Glasgow. (n.d.). Policy on the use of data in the support of student learning (Learning Analytics). Available at https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/senateoffice/policies/regulationsandguidelines/learninganalyticspolicy/#1.introduction,2.definitions,11.linkstootherrelevantpoliciesandprocesses. Accessed 26 May 2022.

University of Sydney. (2016). Principles for the use of University-held student personal information for Learning Analytics at the University of Sydney. Available at https://www.sydney.edu.au/education-portfolio/images/common/learning-analytics-principles-april-2016.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

University of Wollongong. (2017). Learning Analytics data use policy. Available at https://documents.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@gov/documents/doc/uow242448.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Uttamchandani, S., & Quick, J. (2022). An introduction to fairness, absence of bias, and equity in learning analytics. Handbook of Learning Analytics (pp. 205–212). Society for Learning Analytics Research (SOLAR).

Viberg, O., Hatakka, M., Bälter, O., & Mavroudi, A. (2018). The current landscape of learning analytics in higher education. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 98–110.

Wilson, A., Watson, C., Thompson, T. L., Drew, V., & Doyle, S. (2017). Learning analytics: Challenges and limitations. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(8), 991–1007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mavroudi, A. (2023). Challenges and Recommendations on the Ethical Usage of Learning Analytics in Higher Education. In: Viberg, O., Grönlund, Å. (eds) Practicable Learning Analytics. Advances in Analytics for Learning and Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27646-0_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27646-0_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-27645-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-27646-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)