Abstract

Gi, a 34-year-old second-generation Korean American man, presented to treatment with pronounced and longstanding anxiety in many social situations, which significantly impaired his functioning (e.g., his perceived ability to run errands in crowded stores and care for his ill father). Gi engaged in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Key cognitions and biased cognitive processes that were maintaining his anxiety included a judgment that others frequently reject him, an assumption that if he expressed his own needs, then he would be unreasonably burdening others, and a core belief that he was incompetent, along with a pervasive tendency to make negative interpretations about his abilities in most social situations. He experienced marked functional improvements and reduced anxiety throughout his 17-session course of treatment. Gi’s case and treatment are detailed throughout this chapter to illustrate how individual CBT for social anxiety disorder can be implemented. Special discussion of how the clinician continuously and collaboratively modified her case conceptualization and intervention approaches with reference to aspects of Gi’s identities and in response to her own missteps are offered throughout.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Case

1.1 Presenting Problem

Gi, a 34-year-old second-generation Korean American man, lives with his wife, adolescent daughter, and biological parents. Gi is the full-time caretaker of his father, who has late-stage colon cancer, and Gi is responsible for running the majority of the family’s errands. Gi and his wife recently sought treatment for their 14-year-old daughter, Hea, who has been experiencing depressed mood and anxiety in social situations over the past year. After a few family therapy sessions, Hea’s therapist hypothesized that Gi’s long-standing patterns of social avoidance and accommodation behaviors were interfering with Hea’s treatment. Motivated to support his daughter more effectively, Gi presented to individual treatment.

1.2 History

Gi described that, during his adolescence, his parents only seemed to share happy, positive emotions with him and his younger brother. Negative emotions, on the other hand, were ‘brushed under the rug.’ Further, due to his parents’ lack of English language proficiency, Gi was often expected to communicate on their behalf with doctors, car mechanics, and other service providers. Although Gi wanted to help and his parents were very appreciative, Gi noticed that these service providers always seemed to be in a rush to end the conversation with him. He started to worry that this meant they were bothered by his ‘stupid’ questions. Finally, Gi experienced his classmates as critical and rejecting throughout his childhood. For example, he shared that they would make fun of him for being sweaty and smelly after recess. Likely due to these early formative experiences, Gi developed beliefs that sharing negative emotions with others is rude and burdensome, that he is incompetent and an annoyance, and that others are critical and rejecting. Gi’s social anxiety is longstanding but had recently become more impairing and pressing due to his father’s medical deterioration and Gi’s subsequent need to communicate with many medical professionals. Also, Gi recognized that he needed to enter more social situations with his daughter as part of her treatment, which he is committed to supporting. Further, self-critical thoughts about jeopardizing his daughter’s treatment and guilt around modeling socially avoidant tendencies throughout her childhood have contributed to Gi’s worsened mood and low self-esteem, which in turn made him more certain that others will judge him harshly.

1.3 Chief Symptoms

Gi described a very limited social life outside of his family. When in public or while talking to service providers on the phone, he noted experiencing blurred vision, racing heart, shaking and sweaty hands, and a red face. He also reported trouble speaking loudly enough to be heard. Because of this, he shared that it is very distressing to run errands for his family, to communicate with Hea’s teachers, or to go on family outings given he thinks that others will judge him for these ‘weird’ and ‘rude’ displays of anxiety. However, because duty to family and personal responsibility are very important to Gi, he would endure these everyday tasks with significant distress while going to extreme lengths to mitigate the perceived risk of being judged negatively during them. For example, Gi would only go to the grocery store when fewer than 15 cars were in the parking lot, and he never entered an aisle that had more than one other person in it. If ‘too many’ cars were in the parking lot, he would leave and come back later in the day. If the final item on his shopping list was in a crowded aisle, he would either walk around the store for as long as it took until the aisle cleared, or he would leave without buying what he needed. Gi shared that he found the amount of time and effort he put into this planning and avoidance pattern very restrictive and exhausting. At the time of intake, Gi met criteria for social anxiety disorder and comorbid major depressive disorder, single episode, mild. Social anxiety disorder was conceptualized as the primary diagnosis given Gi’s depressive episode seemed to be driven by self-critical thinking tied to his persistent social avoidance.

2 Main Cognitions Targeted

Guided by the cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (Beck, 2020) framework, the therapist approached Gi’s case with special attention to the interpretations, assumptions, and beliefs that seemed to maintain his social anxiety. The way Gi saw himself and others’ views of him seemed to be informed by a deeply held belief that “I am incompetent” and an expectation that others are critical and rejecting. This, coupled with dysfunctional assumptions that “I should never waste someone’s time or get in someone’s way,” “Asking for help is annoying,” and “It’s rude to show negative emotions to others” contributed to Gi’s experience of the world as a socially threatening place. From a CBT perspective, Gi’s fear and avoidance of social situations was understandable given these beliefs and assumptions: he saw himself as both incompetent and unable to ask for help, he thought others were likely to be harsh and rejecting, and he thought showing signs of anxiety would give people more reason to reject him for “being rude.”

To promote Gi and the therapist’s shared treatment goal of reducing rigid avoidance and excessive planning around activities of daily life, in addition to exposure exercises (see below), the therapist identified the need to increase Gi’s perceived competency, reduce Gi’s fear of negative evaluation, and help Gi gain a more balanced perspective on help-seeking and emotional disclosure. Knowing that deeply held beliefs and dysfunctional assumptions like those expressed by Gi are challenging to shift directly (Beck, 2020), the therapist first worked with Gi to identify and shift situation-specific negative automatic thoughts throughout treatment. This process was expected to undermine the legitimacy of Gi’s core beliefs and dysfunctional assumptions over time (Beck, 2020). For example, when imagining what it might be like to order food for his family from a drive-thru, Gi predicted, “I’ll get so anxious that I won’t be able to function and all the cars behind me will start honking and yelling at me for being too slow.” This thought relied on the assumption that he was incapable of ordering food without making others angry with him. Believing in the accuracy of his worst-case scenario prediction, Gi anxiously avoided the drive-thru which, in turn, meant that his core belief was never questioned by disconfirming evidence.

Gi also tended to make assumptions about what others were thinking about him. Sometimes this happened as a statement that raced through his mind (e.g., “The store clerk thinks I’m rude”), and other times he pictured people laughing at him behind his back, like after he walked past them in the grocery store. Gi treated these thoughts and images as evidence that others do reject him. Even though they weren’t reality-based, these thoughts maintained his fear of negative evaluation and avoidance of social situations. Relatedly, Gi also tended to think in extremes: “I forgot to change my dad’s colostomy bag earlier today, I’m a terrible son.” His incredibly high standards with no margin for error set him up to fall short, which he would then take as further evidence that he was in fact incapable.

The therapist’s case conceptualization therefore focused on how these types of dysfunctional cognitions – predicting that the worst possible outcome would come true (catastrophizing/fortune telling), assuming that he knew what others were thinking about him (mind reading), and extreme thinking (all-or-nothing thinking) – maintained Gi’s unhelpful behavioral responses and prolonged his emotional suffering. See Fig. 16.1 for a representation of the relationship between Gi’s cognitions, physical sensations of anxiety, and behavioral responses.

3 Treatment

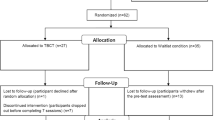

In this section, Gi’s 17-session course of treatment is presented, focusing on collaborative efforts to identify and shift unhelpful cognitions. Gi’s treatment was divided into three phases. The main treatment aims and interventions used during each phase will be outlined, and it will be discussed how collaborative empiricism, including the use of routine outcome monitoring and being responsive to Gi’s cultural context and preferences, informed treatment decisions throughout.

3.1 Phase 1 (Sessions 1–6)

Gi presented to his intake appointment via telehealth during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the beginning of his initial session, Gi’s affect was anxious, and his face was so red and heated that his glasses became fogged. Based on his anxious presentation, the therapist created space to explore how Gi felt about the present meeting and normalized that many people feel uncomfortable when starting therapy.

-

Therapist: It’s really nice to meet you, Gi. You know, people feel all sorts of ways when they start therapy. Sometimes they’re excited and hopeful. Other times they’re terrified or anxious. Maybe even angry or embarrassed. Sometimes they have a mixture of feelings, even ones that don’t seem like they should go together. How do you feel about being here today?

-

Gi: Kind of embarrassed, I guess.

-

Therapist: It can be really vulnerable to start this process. Being embarrassed usually makes people want to hide. I’m really impressed that you came today even though you’re feeling embarrassed. That’s a strength that I think will really help you pursue your treatment goals. Tell me more about why you’re feeling embarrassed.

-

Gi: I don’t know… It’s just…I’ve had a hard time with social things for a long time. It’s really taken over. It seems silly that I’ve waited this long. Anyone else would have gotten help years ago…I guess I’m just a coward.

Already Gi and the therapist have uncovered an unhelpful cognition. The therapist took this opportunity to briefly comment on the power of thoughts like those to stir up emotions (embarrassment) and behaviors (delayed treatment seeking) that can keep people stuck. This demonstrated to Gi that the process he described as ‘silly’ is actually understandable and allowed the therapist to begin to familiarize Gi with the CBT model. The therapist also shared with Gi that over a third of people with social anxiety disorder do not seek treatment for 10 or more years (ADAA, 2022). Sharing this statistic conveyed the therapist’s deep appreciation for how challenging it must have been for Gi to take a risk by showing up to therapy. It also normalized that many people experiencing similar fears wait just as long, if not longer, to ask for help, which gently offered evidence to counter the unhelpful thought Gi expressed. At this point, Gi’s face became less red, and he was able to talk more openly about his experiences.

To guide case conceptualization and collaborative treatment planning, the therapist, who identified as a non-Hispanic white woman in her late 20 s, created space to explore how Gi saw aspects of his identity in relation to the treatment process.

-

Therapist: What do you see as the most important parts of your identity? Some people raise their gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and culture, religion, or ability status. Some people raise multiple identities or ones beyond those I offered.

-

Gi: That I’m a second-generation Korean American.

-

Therapist: What are the most important aspects of this identity for you?

-

Gi: Being there for my family and supporting them any way I can.

-

Therapist: You really value your family. What aspects of this identity do you think make a difference for your mental health?

-

Gi: … It was hard to come in for this. We don’t talk about mental health very openly.

-

Therapist: You’re taking a risk here. How do you feel to be talking to someone about your mental health? Especially someone who is White, who doesn’t share this important part of your identity?

-

Gi: I’d be uncomfortable talking to anyone about this stuff, to be honest. In some ways it might even feel a bit easier to talk to you because you aren’t Korean. I don’t know… but I guess it’s important to me to make sure other people, even people I don’t know, are not put out by me. I guess I worry that a therapist with Western values might try to get me to put myself over others. That wouldn’t feel right to me.

The therapist non-defensively reflected his concern and positively reinforced him for raising it, and joined with him by sharing that the therapist’s role is to help him find ways of living that are in line with his values and preferences, but that are more effective and sustainable for him in the long term than what he has been doing up to this point. Gi then shared that his primary goal for treatment was to be able to run errands when it’s most convenient for him and to not have to schedule around how many other people were likely to be where he needed to go.

-

Therapist: It’s exhausting to live your life on anxiety’s terms. Anxiety is really good at protecting us from danger. If something is dangerous, it makes a lot of sense to avoid it. Back away from the cliff’s edge on a rainy day! The trouble with anxiety starts when anxiety makes us think that we’re in danger when it’s not likely that we’re facing an objective threat. Anxiety is acting as a false alarm. But our body doesn’t really know the difference between anxiety due to a true threat and anxiety due to a false alarm. It feels the same and it’s really uncomfortable. I’m curious, when you’re in the store and you decide not to turn down the crowded aisle, what happens next?

-

Gi: I feel relieved. My hands stop shaking. No one said anything to me.

-

Therapist: Exactly…phew! The trouble is, now, without realizing it, you’ve learned that the reason nothing bad happened is because you avoided going down that crowded aisle. You never get to see what would have happened if you had walked down that aisle. Maybe no one would have even noticed you. Or, maybe if someone did say something kind of rude, you could have handled it okay. You have no idea. But, if you think the reason you stayed safe is because you avoided the aisle, what do you guess you’re likely to do the next time you see that the bread aisle is crowded?

-

Gi: I’d avoid it.

-

Therapy: Totally! And avoiding it makes perfect sense given the contingency that you’ve set up. But it turns out that anxiety is really good at getting us to overestimate the likelihood that something bad will happen and underestimate our ability to manage bad things that do happen. So, if we only listen to our anxious thoughts, our life can get small. We never go down the bread aisle if someone else is there. In our work together we’re going to find a bunch of different ways to reconsider anxious thoughts so that you get to decide when and how you do something, not anxiety. How does that sound?

The therapist then introduced the rationale for exposure therapy from an expectancy violation perspective. Whereas exposures were initially assumed to operate through habituation (Foa & Kozak, 1986), the expectancy violation theory of exposure assumes that exposures work by challenging long-standing beliefs through hypothesis testing (Craske et al., 2014): The patient articulates their feared expectancies ahead of time, carries out the exposure, and then makes sense of what did or did not happen and why. Oftentimes the patient is surprised to find that the terrible outcomes they expected to happen didn’t happen, which promotes cognitive change. As such, exposures from this perspective are quite similar to behavioral experiments.

To increase Gi’s buy-in to this treatment approach, the therapist used motivational interviewing techniques (Miller & Rollnick, 2012) to amplify Gi’s reasons for choosing to tolerate his anxiety while ‘testing out’ his anxious predictions through exposures and behavioral experiments. He reported being motivated to engage in this treatment to support his daughter, spend less time planning errands, and spend more time with his ailing father. The therapist ensured that Gi understood why treatment would initially focus on approaching anxiety-provoking activities and shared that CBT is the gold-standard treatment approach for social anxiety disorder. The therapist also asked Gi what he thought about this treatment approach given his personal and cultural views. Because Gi reported that he thought the treatment approach was acceptable and in line with his goals, the remainder of the intake session involved identifying the social domains which bring up the most anxiety for Gi using the Social Anxiety Questionnaire (Leahy et al., 2012). He also completed the straight-forwardly worded factor of the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale (BFNE-S) (Norton & Weeks, 2019), which has good reliability for Asian samples (Harpole et al., 2015), and the Social Thoughts and Beliefs Scale (STABS) (Turner et al., 2003).

Gi’s second session focused on collaboratively building an exposure hierarchy. The therapist then encouraged Gi to pick an activity on his hierarchy to try before the next session. The remainder of the session was spent filling out the ‘Before Exposure’ section of the Testing It Out worksheet (Table 16.1; adapted from Craske et al., 2014), which was designed to establish the expectancies that he would test through the exposure. Gi predicted that if he tried to grab an item from the middle of a crowded grocery aisle that he would get so anxious that his shaking hand would knock things over and the shoppers around him would become annoyed with him. For homework, Gi completed his first exposure activity. Counter to his prediction, Gi found that he was able to get a jar of pasta sauce without making a mess or getting into a confrontation with the other shoppers even though he was extremely anxious, and his hands were shaking uncontrollably. This experience violated his expectation and taught Gi that his ability to function does not totally disappear when he is anxious. As such, this experience began to undermine Gi’s core belief that he was ‘incapable’ because he saw first-hand that he was able to perform a task that he otherwise predicted he would not be able to perform. It also challenged his biased probability estimation by showing him that his feared outcome did not happen as often as he expected. At the beginning of the next session, the therapist supported Gi in filling out the rest of the Testing it Out worksheet to consolidate the new learning offered by this disconfirming evidence.

Gi repeated this process over the next four sessions for a range of activities. To generalize his new learning, and to further undermine his core belief that he is ‘incapable,’ the therapist encouraged Gi to try activities in different domains that mattered to him (i.e., changing a doctor’s appointment, asking a store clerk for help, ordering something from a drive-thru). After the first two exposure activities, the therapist discovered that Gi had been mentally rehearsing what he would do or say leading up to his exposures to reduce the perceived likelihood that he would ‘mess up.’ The therapist labeled this as a safety behavior (Piccirillo et al., 2016) that likely maintained his anxiety by teaching him that he can complete tasks only if he spends considerable time planning them out in his head. The therapist emphasized the importance of trying out his exposure tasks without mental rehearsal to facilitate more adaptive learning so that he can perform activities of daily life without excessive preparation. After labeling and then reducing this safety behavior in future exposures, the therapist noticed that Gi had begun to report spending less time planning and delaying errands and that he thought anxiety and avoidance were not getting in the way of his personal goals as often. Despite these positive behavioral changes, and higher levels of self-efficacy, his BFNE-S and STABS scores had not reduced. This suggested that the therapy had thus far not sufficiently helped Gi internalize desired new learning across all important areas of his thinking. Specifically, Gi remained convinced that if he did not perform a task ‘correctly’ and unobtrusively (e.g., if he did drop the jar of pasta sauce), then he would be seen as rude and be rejected. The therapist hypothesized that, although the exposure exercises had helped Gi begin to see himself as more capable, which had reduced his avoidance, his ‘successful’ completions of these exposure tasks did not challenge his expectancy that even minor missteps would result in ridicule, which kept his fear of negative evaluation and anxious thinking elevated.

To address the remaining high fear of negative evaluation and rigid anxious thinking, the therapist considered assigning exposures where Gi made mistakes in front of other people. However, hypothesizing that Gi would find those exposures less acceptable based on the cultural norms he described during an earlier conversation, the therapist decided to first offer additional cognitive strategies that might help Gi to develop more balanced thinking around the interpersonal significance of making mistakes. The therapist also thought it might be helpful to more closely explore if and how aspects of Gi’s cultural identity relate to his fear of negative evaluation. With these considerations in mind, the therapist decided to shift towards directly exploring the thoughts and feelings Gi held about himself in interpersonal situations in a second phase of treatment (e.g., “Sharing negative emotions is burdensome to others and rude”). With this shift in therapy, the therapist hypothesized that promoting more flexible, values-aligned thinking would amplify the positive learning from exposures and behavioral experiments, and increase the likelihood that Gi would be willing to engage in future exposures where he intentionally made mistakes.

3.2 Phase 2 (Sessions 7–12)

To lay the foundation for flexible thinking skill development, the therapist provided psychoeducation around different styles of unhelpful thinking. As such, Gi was encouraged to log thoughts and images that occurred throughout the week that elicited strong emotions of anxiety, sadness, or shame. From the thought logs he brought to the session, Gi noticed that he tended to catastrophize, mind read, and fall into all-or-nothing thinking.

-

Therapist: When the hospice nurse asked you when you had last changed your dad’s colostomy bag, what went through your mind?

-

Gi: I was mortified.

-

Therapist: And what thought or image went through your mind?

-

Gi: She thinks I’m neglectful.

The therapist then used Socratic questioning to help Gi label this thought as mind reading and explore the evidence for and against this negative automatic thought. For example, when Gi said evidence ‘for’ the thought was “She just looked disgusted in me,” the therapist asked if that evidence would hold up in court. When he admitted it wouldn’t, the therapist helped him identify concrete pieces of evidence by asking questions like “If someone else had been watching, what would they have noticed?” Throughout this exercise, Gi was able to construct a more balanced thought (i.e., “I’m not sure what she thought, but I think she was trying to help me find ways to take care of Dad more effectively and easily. She probably knows better than most people how much work it takes to look after someone who needs so much care, and it sounds like she’s had these conversations with other caregivers before and she didn’t seem to judge them.”). He reported that his feeling of being mortified decreased from 90 to 40 (out of 100) after he restructured his initial “She thinks I’m neglectful” negative automatic thought to this more balanced interpretation. However, his feelings of guilt did not diminish after generating this restructured thought, which suggested to the therapist that another thought was driving his feeling of guilt. Gi’s completed Though Record is reproduced in Table 16.2.

-

Therapist: I notice that your guilty feeling is still at 95/100. That’s a really powerful feeling. I wonder, what does it mean about you that you forgot to change his colostomy bag for about a half hour?

-

Gi: That I’m a terrible son.

The therapist thought back to an earlier conversation when Gi shared that he deeply valued his family and their comfort, and reflected on how painful this situation must have been, given how at odds his interpretation of this event was with what he cares about most. The therapist then drew a line on a piece of paper and labeled one end with ‘terrible son’ and the other end with ‘perfect son.’ Gi was encouraged to write down examples of things that he thought a perfect son does and examples of things that he thought a terrible son does. The therapist also encouraged him to generate examples that weren’t so extreme (e.g., “What would a son who is exactly in the middle of this continuum do?”; “What would a son who is 20 percent away from being terrible do?”). Finally, Gi was asked to place on the continuum where he thought that he fit. Gi was surprised to see that, even though he didn’t see himself as perfect, his actions didn’t seem to belong anywhere near the terrible son label. He reported that using the continuum method helped relieve him of some guilt.

The therapist was impressed by how quickly Gi learned these cognitive restructuring skills, but also suspected that Gi’s value of prioritizing the comfort of others might still be at odds with how he was thinking about exposures. With this in mind, the therapist asked:

-

Therapist: We’ve talked before about how aspects of your identity as a Korean American sometimes impact your beliefs and what matters to you. I am curious if you think your different identities influence how you think about being anxious in front of others?

-

Gi: I learned from my parents not to bring up negative emotions, only happy ones. It wasn’t that they were cold, it’s just that they would switch the topic and bring up something happy the minute me or my brother said something wasn’t going well. I guess that taught me that showing negative emotions makes people uncomfortable and it’s rude to do that. I never want to make anyone uncomfortable. Like when my hands are shaking in the grocery store… I think it makes the other shoppers feel weird and I don’t want to cause them to feel that way, so I stay away.

-

Therapist: What are the parts of that upbringing that you value and want to hang on to?

-

Gi: I want to make sure people feel comfortable. I don’t want to be rude.

-

Therapist: Being polite is important to you. Are there any parts of that upbringing that you don’t want Hea to hold onto in quite the same way as you?

-

Gi: I don’t want her to feel like she is alone…that she’s wrong for feeling how she’s feeling. That she has to hide away.

The therapist used Socratic questioning to support Gi in exploring his values in this space. As part of this, the therapist circled back to better understand Gi’s definition of what it means to be rude, and supported Gi in defining rude behavior from different perspectives: within his culture, within his family, within the majority culture in the Southeastern United States. The therapist asked how the various exposures he had done fit within his definitions of rudeness. Through this conversation, Gi began to think that being anxious in front of others might not be as rude as he originally thought, which signaled a shift in this previous dysfunctional assumption which the therapist hypothesized had been driving Gi’s distress across a wide range of interpersonal events throughout his life. He also began to focus on how pushing himself to do things in public even when he is anxious is in line with his value of supporting Hea in her treatment. At this point, Gi started to spontaneously engage in exposures without pre-planning in addition to those that were set for therapy homework. He also started to design exposures where he intentionally did things that he thought might realistically irritate other people (e.g., he would take ‘too’ long to order in the restaurant, he would ask the store clerk for something and then change his mind about what he wanted).

Based on the CBT case conceptualization, it was believed that these exposures more directly targeted his expectancies that if he wasn’t perfect, then others would be rejecting him. Because he directly obtained disconfirming evidence (e.g., when he stammered excessively when placing an order, the drive-thru worker was still able to place the order correctly and did so without raising her voice or yelling at him to ‘spit it out already’), his thoughts began to shift. His STABS and BFNE-S scores decreased accordingly, and he reported feeling like he had met his functional goals. The therapist then began to engage Gi in termination planning. Gi reported that he thought he would be best positioned to continue improving after termination if he was able to be more emotionally vulnerable with his cousin and wife. With this new treatment aim in mind, the therapist and Gi moved to Phase 3.

3.3 Phase 3 (Sessions 13–15)

Gi had good insight into the cognitive barriers that made it anxiety-provoking and hard for him to share more openly with his wife and cousin. He worried that his wife would think he was weak (mind reading) if he told her that he sometimes struggles to do basic errands and that his cousin would stop counting on him if he knew that Gi went to therapy (catastrophizing). However, Gi strongly believed that it was important enough to strengthen his emotional connections with them that he was willing to tolerate the risk of sharing.

Gi was able to more independently apply the skills that he learned in Phases 1 and 2 to support this goal. The therapist positively reinforced Gi for using his skills effectively to arrive at more balanced thoughts, and also positively reinforced him for deciding to test out his feared predictions by initiating increasingly disclosing conversations with his cousin and wife, in line with his values. To help Gi have the most success in these conversations as possible, the therapist engaged Gi in role plays during session. This encouraged Gi to think through and practice what he wanted to communicate to them. During this phase of treatment, the therapist also encouraged Gi to use the ‘Bull’s Eye Exercise’ (Hayes et al., 2012) to track how values-aligned his conversations were with his cousin and wife during each week. Having a plan and keeping in mind why it was important for him to take these risks made it easier for Gi to initiate these conversations and, in turn, test his unhelpful beliefs about how his family members would respond. After three sessions, his Bull’s Eye responses showed greater values-action congruency and Gi described having connected emotionally with his cousin and wife in ways that felt very comforting and did not result in his feared outcomes. In fact, he noticed that his cousin seemed to come to him more often.

3.4 Termination and Booster Sessions

Throughout treatment, the therapist regularly presented termination as an opportunity to commit to independent use of the skills developed during treatment. During termination, the therapist and Gi celebrated treatment progress and explored Gi’s thoughts and feelings about discontinuing regular meetings. As part of relapse prevention, the therapist supported Gi in proactive coping to plan for future situations when there may be high risk for increases in anxiety and talked through how Gi would know to pursue additional therapy in the future. Gi was encouraged to list out the therapy skills that he found most helpful, and was asked to teach back the principles of change underlying these skills on his list to ensure that he had accurately consolidated what was taught in therapy. The therapist emphasized that regular use of these skills is key to maintaining treatment gains and continuing to improve. They set a booster session for one month later to check in on progress and troubleshoot any unforeseen challenges since termination. At the end of the booster session, Gi said “I didn’t know that treatment could help me as much as it did” and he described a confidence that “He can handle it” when anxiety spikes in the future. A summary of Gi’s treatment aims, associated interventions, and measures of progress is provided in Table 16.3.

4 Special Challenges and Problems

Gi’s motivation, engagement, and willingness to try things out were great strengths that positively influenced his course of treatment. Even still, there were several challenges that Gi and the therapist needed to address to make the treatment work for him. In this section, three of these challenges are highlighted and it is discussed how the therapist responded to each.

4.1 Difficulties Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic

The entirety of Gi’s treatment took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, prior to vaccinations being widely available to the public. This introduced two complications from a social anxiety treatment perspective. First, public health guidelines all recommended that adults wear face coverings when entering stores. Given that anxious avoidance was particularly impairing for Gi within stores, it was important for him to complete exposures in these locations. From an expectancy violation perspective, however, this raised the possibility that Gi might attribute the outcomes of his behavioral experiments to the fact that he was wearing a face covering rather than to his ability to effectively tolerate anxiety with or without a face covering.

-

Therapist: It sounds like you did some really good learning, there! Your ability to function doesn’t go totally away even when you’re super anxious. That’s important to know. I wonder, what do you think would have happened in that grocery store aisle if you hadn’t been wearing a face covering?

-

Gi: I would have been even more anxious…the mask keeps others from seeing how red my cheeks get. It helps me feel a little more invisible.

-

Therapist: Hmmm. I’m curious, would you still have been able to function if you were feeling more anxious and others could have seen your face?

-

Gi: …I’m not sure. Maybe? The mask definitely helps, though.

The therapist helped Gi recognize that although face coverings were a reasonable precaution given the current environment, they also functioned as a safety behavior (Piccirillo et al., 2016). Given that exposures and behavioral experiments are meant to promote cognitive shifts, it was important that Gi did not learn that he was only able to function while anxious because he was less visible to others. However, it would have been inappropriate for the therapist to instruct Gi to carry out his grocery store exposures without wearing a face covering. As such, the therapist and Gi did the following: they applied cognitive restructuring skills to reframe Gi’s beliefs that wearing a face covering is necessary to function while anxious; they planned exposures that did not require Gi to wear a face covering (e.g., ordering from the drive-thru, calling to reschedule doctor appointments); they planned for how Gi would set up and re-do his grocery store exposures in the future when masks were no longer a public health recommendation.

Additionally, given that acts of racism against Asian individuals increased in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gover et al., 2020), it was important for the therapist to differentiate between Gi’s anxiety in public spaces due to social anxiety versus due to fear of racist abuse.

-

Therapist: There has been a sickening rise in acts of hate and racism against Asian individuals within our country and local community since the onset of this pandemic. Many Asian individuals are understandably feeling less safe in certain public settings because of this. I wonder, has your anxiety when going to places like the grocery store changed since the pandemic began?

-

Gi: I’m very angry about how Asian people are being treated and talked about by large groups of Americans… I don’t know, though, for me… the anxiety that I’m feeling hasn’t really changed because of this.

The therapist validated Gi’s anger and created space for him to share and process additional thoughts and feelings tied to the social climate. Knowing that Gi’s anxiety was not driven by fear of racist acts, the therapist decided that it was appropriate to continue with the plan to introduce the rationale of exposures and pursue them as part of treatment. However, had Gi endorsed fear of racist acts, the therapist would have needed to carefully consider which aspects of exposure therapy may have still been beneficial and which aspects may have been harmful (e.g., by dismissing or invalidating Gi’s concerns about the likelihood of racism; by putting Gi in situations where he was likely to experience and re-experience racism).

4.2 Difficulties Associated with Inhibitory Learning

After around seven sessions, the therapist uncovered an unexpected cognitive barrier that seemed to partially explain why Gi’s early exposures did not seem to meaningfully shift his fear of negative evaluation or socially anxious thoughts. Through Socratic questioning around what it meant to Gi that many of his expectations did not come true, he said that it meant “I have wasted my life and hurt my daughter for no reason.” The therapist learned that this thought made Gi particularly sad and angry. While it is common for socially anxious people to mourn their years lost to anxious avoidance, this thought ironically led Gi to tell himself that the next time he entered an anxiety-provoking situation, his feared outcome would happen. This way, he could tell himself there was a reason for his years of avoidance and anxiety, thus (temporarily) reducing his anger and sadness. Of course, this pattern reinforced his exaggerated beliefs about the likelihood of negative outcomes, thereby maintaining his anxiety and fears of evaluation.

After uncovering this pattern, the therapist had Gi conduct a functional analysis of this thought. Gi was able to see that while it helped him feel a bit better in the short term, it also kept him stuck in the long term. After calling attention to this thought process, Gi was able to then effectively engage in cognitive restructuring to find a more adaptive way to respond to the thought “I have wasted my life and hurt my daughter for no reason.” Had the therapist helped Gi better anticipate what it might feel like to have his expectancies disconfirmed, it is possible that Gi’s defensive reaction to experiencing loss and regret could have been addressed sooner. Similarly, if the routine outcome monitoring schedule would have included measures of depressive symptoms and cognitions, the therapist may have picked up on this underlying self-critical thought process more quickly.

4.3 Difficulties Associated with Overly Positive Self-Talk

Gi had a long-standing history of trying to counter anxious thinking and post-event processing through overly positive self-talk. He also tended to berate himself for having ‘irrational’ thoughts.

-

Therapist: How do you feel when you tell yourself that your thoughts are irrational?

-

Gi: I feel bad…embarrassed.

-

Therapist: Does telling your thoughts that they’re irrational seem to make them go away or change them somehow?

-

Gi: No! I wish. They’re still there. I just try to crowd them out by thinking really positively…but….

-

Therapist: Do you believe those positive thoughts that you come up with?

-

Gi: Not really. But I keep trying to tell myself them over and over so my stupid irrational thoughts will go away. But they never do.

-

Therapist: That sounds really exhausting. You want to think positively, but telling yourself overly positive thoughts doesn’t work…those positive thoughts aren’t even close to being on the same page as the actual story that you’re living. They aren’t believable. The goal here isn’t to trick yourself into thinking positively, or to criticize yourself for being ‘irrational,’ it’s to figure out when a thought isn’t helping you and to learn how to step back and figure out a thought that better captures the whole story, is believable, and supports you in doing what is effective for your goals.

In this conversation, when introducing cognitive restructuring and styles of unhelpful thinking, and when processing expectancy violations, the therapist took special care to avoid using potentially stigmatizing language. For example, although some patients like using the term ‘cognitive distortions,’ the therapist hypothesized that Gi might experience that as evidence that the therapist thought he was in fact irrational and silly. Instead, the therapist used the term ‘unhelpful thinking styles.’ Gi later said that he found it much easier to approach his anxious thoughts when he labeled them as unhelpful rather than as irrational. He also found it comforting to learn that his thoughts didn’t need to be entirely positive for them to be helpful.

5 Summary, Conclusions, and Learning Points

Gi made great progress during treatment. A wide range of flexibly employed strategies designed to shift Gi’s thinking helped him make significant changes within his life and family, which ultimately improved his quality of life and his relationships. After treatment, he reported reduced anticipatory anxiety, reduced post-event processing, greater willingness to tolerate anxiety to pursue his goals and to support Hea’s treatment progress, greater acceptance of his emotions, increased ability to balance anxious and negative self-focused thinking, increased confidence, and greater engagement in emotional support-seeking behavior from his wife and cousin. Prior to treatment, he reported spending approximately 7 hours a week planning and delaying errands due to his anxiety and said that anxiety/avoidance got in the way of his goals ‘a lot.’ At his booster session, Gi said he was spending around 20 minutes a week on average planning and delaying errands and said that anxiety/avoidance got in the way of his goals ‘barely any’ each week. His BFNE-S and STABS scores also decreased from 36 and 72 to 21 and 49, respectively, from intake to booster. These individual progress markers positively impacted Hea’s course of treatment given that Gi had begun to regularly model and support approach-oriented coping strategies.

Taken together, the therapist also took a great deal away from Gi’s treatment. Most significantly, this case underscored the importance of continuously keeping aspects of a patient’s identity in mind. Aspects of Gi’s identity cut across all phases of the treatment. Had the therapist failed to create space to explore these aspects during different points in treatment, it’s quite possible that Gi would have terminated treatment prematurely. As such, this case reinforced for the therapist the need to be continuously thinking about when and how to explore whether there are aspects of a patient’s identity that influence how principles of change fit them and their values. Additionally, this case demonstrated that exposures going ‘well’ can also be threatening to patients for any number of reasons. This taught the therapist to create space for mixed reactions to exposures, not just enthusiasm.

References

Anxiety & Depression Association of America. (1.12.2022). Social anxiety disorder. https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/social-anxiety-disorder.

Beck, J. S. (2020). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20

Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., & Langton, L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

Harpole, J. K., Levinson, C. A., Woods, C. M., Rodebaugh, T. L., Weeks, J. W., Brown, P. J., Heimberg, R. G., Menatti, A. R., Blanco, C., Schneier, F., & Liebowitz, M. (2015). Assessing the straightforwardly-worded Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale for differential item functioning across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(2), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9455-9

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Leahy, R. L., Holland, S. J. F., & McGinn, L. K. (2012). Treatment plans and interventions for depression and anxiety disorders (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping patients change behavior (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Norton, P. J., & Weeks, J. W. (2019). A multi-ethnic examination of social evaluative fears. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.008

Piccirillo, M. L., Taylor Dryman, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2016). Safety behaviors in adults with social anxiety: Review and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.00

Turner, S. M., Johnson, M. R., Beidel, D. C., Heiser, N. A., & Lydiard, R. B. (2003). The social thoughts and beliefs scale: A new inventory for assessing cognitions in social phobia. Psychological Assessment, 15(3), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.384

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Daniel, K.E., Teachman, B.A. (2023). “I Don’t Want to Bother You” – A Case Study in Social Anxiety Disorder. In: Woud, M.L. (eds) Interpretational Processing Biases in Emotional Psychopathology . CBT: Science Into Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23650-1_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23650-1_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-23649-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-23650-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)