Abstract

Intergenerational trauma as a means of understanding and informing the healing of Indigenous and Latinx Boys and Young Men of Colour (BYMOC) is a growing area of public health and scholarly interest. The escalation of violent, trauma-inducing anti-Latino, anti-immigrant racism, and catastrophic encounters with immigration authorities, police, and the justice system in the U.S. make it imperative to understand the extent and gravity of the trauma, and develop interventions that address its impact on BYMOC, particularly Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous youth. This chapter introduces the conceptual framework for National Compadres Network’s La Cultura Cura approach and El Joven Noble youth development curricula for Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano communities. We present recent agency data to show that deepening authentic cultural identity, intergenerational connectedness, and support could soothe adolescent stress and intergenerational trauma. This discussion has implications for refining our understanding of health and wellbeing, health practice, agency-level program design policy, and evaluation research for BYMOC.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Cada cabeza es un mundo: An Introduction

On the surface, this chapter is about healing the self-destructive behaviour of Indigenous and Latinx Boys and Young Men of Colour (BYMOC) in the U.S. and guiding them toward lives that honour both their ancestors and descendants. Implicitly, it is also an exploration of the limitations of the written word – how effectively meaning can be faithfully articulated and respectfully conveyed across different realities. From 2006 to 2019, we were blessed to host, assist, and translate for a Wirrarika elder and medicine man called Ri’tak’amehFootnote 1 as he helped heal hundreds of people throughout California, Arizona, and Nevada. We observed that most of the people he treated changed in some positive way, even if they did not completely understand the inner workings of his treatment. After his interventions, their faces were less tense than before and their physical movements were lighter. Wary of our own bias, we confirmed observations with subjects and other witnesses. In doing so, we realised that our capacity to understand and explain the healing “mechanism” were challenged by our facility with language. We were also challenged by the boundaries established by the respective cultures in which we were raised. We lived in different realities – not perspectives, nor theories – but realities.

In this chapter, we speak for Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous BYMOC in the United States, and while our instinct is to include the familiar, realities are different. The human impact of genocide of people from the land that was previously Mexico, which is now the United States, is not the same as that for the enslavement of Africans. The experience of Mexicans after the Mexican-American War differs from that of more recent immigrants from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and other Central American countries. The experience of our relatives from other corners of the earth are also distinct. Science complicates our task by insisting that true understanding comes primarily, and some would even say exclusively, through dissecting and analysing – through specificity.

We claim a mechicano indioFootnote 2 philosophical and cultural foundation in speaking to the interconnectedness that unites us. The Indigenous people of Meso-America developed and used two calendar systems for making sense of the world. On the one hand, the 365-day Xiuhpohualli monitored the sun, seasons and was consulted on physical matters, like agriculture; on the other hand, the 260-day Tonalpohualli monitored the manifestations of the soul and was consulted on spiritual concerns that influenced thinking, feeling, and behaviour. We take this two-calendar system as a reminder of the dualityFootnote 3 of life and health – that illness and wellness are simultaneously and inseparably physical and spiritual. As noted, bridging the many realities that constitute life through words is a daunting task. But we take heart in the words that our brother, Ri’ta’kame, left with us – le hacemos la lucha: we’ll put up a battle for the young people whose spirits we call back to the circle.

El Hombre Propone, Dios Dispone: The Proposal

We propose that the self-destructive behaviour of many BYMOC is a misguided attempt to heal woundedness. We subscribe to the term intergenerational trauma to convey the current understanding that, for people of colour, woundedness could be more appropriately seen as violent, terrorizing, and painful disconnections that have occurred over the last 500 years and exacerbated by present-day inequalities and stressors. Given the racially motivated violence that has stewed for centuries and erupted most recently in 2020, we believe the time is ripe for serious consideration of different solutions.

While impossible to establish exact numbers, recent estimates claim that as many as 56 million lives were lost in the century following the European arrival in the Americas (Koch et al., 2019). Historians tell us the violence manifested in many forms – from homicide, uprooting children from family and community, forced labour, and enslavement to the destruction of sacred places of worship – sparking cataclysmic loss and suffering by native peoples. While in current Western clinical terms, the resultant condition among survivors could be understood as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Williams et al., 2017), we prefer the term ‘woundedness’ because it more accurately conveys the pain and collective sustoFootnote 4 – the terror that overwhelmed individuals, families, and communities over generations. Similarly, Brave Heart et al. (2011) uses the term ‘soul wounds’ to emphasize that the damage affects all aspects of the person—from thinking to feeling, behaviour, and spirit.

Another critical point is that soul woundedness is transmitted to successive generations. We are convinced that one mechanism for its transmission is our disconnection from all that makes us whole, including the natural environment that nurtures us. Wounded parents—those who are isolated, depressed, drug-abusing, frustrated, overworked, traumatized, etc. – also wound their children. They hurt children with the words and feelings they project, the values they teach, and their day-to-day interactions. Seemingly oblivious to that reality, current interventions of youth-serving institutions rarely include parents and families. In fact, in a recent listening tour of seven U.S. communities, youth tell us they feel neither represented nor supported, but rather punished by the institutions that have been established to serve them.

When the youth are abused and traumatized at home and in their communities, should it be a surprise that they are overwhelmed with pain and ill-equipped to cope adaptively? They become trapped in a loop of high-risk behaviours. The numbers are clear: Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous and BYMOC, in general, are grossly over-represented in correctional institutions (Dragomir & Tadros, 2020; Jeffers, 2019; Kovera, 2019), bear a disproportionate share of school suspensions, are exposed to excessively violent interactions with police, and surrounded by cultural cues that diminish their identity, damage their self-worth, and condition self-destruction.

In this chapter, we focus our attention on boys and youths of colour, with the understanding that both illness and wellbeing are best understood as relational. As an individual heals, so too does the circle, community and society in which they live. Nonetheless, research indicates that young boys of colour are exposed to higher rates of trauma than other demographics groups (Graham et al., 2017). Moreover, youth of colour are both perpetrators and victims of violence at disproportionally higher rates than other demographic groups (CDC, 2003). Whether we choose to understand the transmission of woundedness as modelling, behaviour reinforcement, or other culturally accepted constructs, boys and youth of colour are trapped in a world of pain, fear and violence. With this in mind, we propose a culturally-rooted way of understanding trauma, its long-term consequences and an intervention that helps young men, feel wanted, transform their pain into compassion, reconnect with their authentic self, and join the circle of life.

Current Practice Concerns in Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano Communities

Research supports the idea that woundedness, more clinically known as a disorder, anxiety, or depression, may indeed be an antecedent of self-destructive behaviour. Substance dependence, depression, acute stress disorder, disruptive behaviour disorders in children (e.g., conduct disorder and oppositional defiance), phobias, sleep disorders (Coll et al., 2012) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are thought to be associated with criminal behaviour (Gibson et al., 1999; Maschi et al., 2008; Spitzer et al., 2001; Wolff & Shi, 2010) and have been suggested to intensify high-risk behaviour, including status offenses (e.g., substance abuse, persistent disobedience, curfew violations, and habitual truancy) (Vanden WallBake, 2013) and illegal offenses (e.g., crimes against a person, inchoate crimes, statutory crimes, crimes against property) (Ardino, 2012).

Research also suggests that Latinx, Mexican Americans, and Chicanos are especially vulnerable to these soul wounds and their transmission across generations because of multiple stressors, including political violence in their home countries and trauma during migration (Cerdeña et al., 2021), settlement-related stress (Santiago et al., 2018), and parenting stress that leads to competence problems for children (Cabrera & Hennigar, 2019). Researchers are also showing a growing interest in intergenerational trauma as a means of understanding stress and wellbeing in Latinx populations (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Isobel et al., 2019). However, much remains unclear about its dynamics, and a better understanding might inform strategies and interventions for resolving the impacts of trauma in Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano communities (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). The escalation of violent, trauma-inducing, anti-Latino and anti-immigrant racism in the U.S. and the increasing frequency of damaging contact with immigration authorities, police, and justice systems make it imperative to develop robust frameworks for understanding.

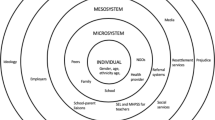

Addressing the omission of macro-level risk factors for intergenerational trauma is a vital point for discussion. Most current research literature on intergenerational trauma in Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano communities focuses on individual risk factors at the expense of structural, social, and cultural forces that also shape behaviour (Cerdeña et al., 2021). For example, research on Mexican American and Chicano adolescents shows that promoting family values, strong ethnic identity, and the use of cultural strengths supports adaptive coping, reduces adolescent problem behaviours (Gonzales et al., 2012) and mitigates the cycle of intergenerational trauma. Gonzales et al. (2020) found that the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) Inventory was not a good fit, while collectivist coping strategies resonated better with Latinx youth, suggesting that relationship- and culture-based approaches to coping could be more appropriate. Furthermore, Andrade et al. (2020) found that deeper ethnic pride and belonging weakened the impact of perceived racial/ethnic discrimination on mental health, suggesting that culturally rooted interventions are more effective for Latinx, Mexican Americans, and Chicanos.

Given the macro-level dimensions of intergenerational trauma, the practice field needs a comprehensive understanding of cultural root-causes of intergenerational trauma for programs to effectively bring not only health but also hope to vulnerable Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano communities. We contend that BYMOC need youth development practices that are culturally rooted and meaningful to them. We discuss below the conceptual framework for such a practice for Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano communities.

La Cultura Cura: Culture as Medicine

Cultura or culture generally refers to the customs and behaviours of people unified through history, language and geography. Our understanding is similar to that expressed by Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961), who saw culture as a set of solutions to basic existential problems. In small groups, values are passed down through personal interactions, with bigger societies preserving and transmitting it through institutions (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2010). Our working definition of cultura refers to a dynamic set of orienting valores (values), passed down from one generation to the next, which are a source of cultural identity, and serve as mechanisms for maintaining interconnectedness, individual health, and family wellbeing. Culture also includes our relationship to that which we may not understand but is nonetheless vital – the spiritual domain of life. In the Americas, our Indigenous ancestors acknowledged, respected, and revered the sacredness of their relationship to all forms of life, including the physical forces that support existence – earth, wind, water, and fire. This appreciation of the interconnectedness of life is one of the main characteristics of what we respectfully call an Indigenous reality. Tello (2018) uses the term Tloque NahuaqueFootnote 5 to convey that sense of sacred interconnectedness, the organizing idea in our philosophy.

La Cultura Cura (LCC) is an Indigenous knowledge-based framework for understanding the cultural grounding of health and for addressing self-destructive behaviour and its associated thinking and feeling processes. In the literature, LCC can be traced back to what researchers call indigenismo, a Civil Rights Era attempt to acknowledge, reclaim, and reconnect people of Mexican and Central American descent to their Indigenous roots devastated by colonisation (Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). The formal foundation of LCC began with a 1988 gathering of nineteen Chicano, Native, Latino community advocates and social service providers. Led by Jerry Tello, Ricardo Carrillo, Jésus de la Rosa, Isaac Cardenas and others, the group developed the basic tenets of LCC to serve others by committing to first addressing their own colonised pain and self-destructive behaviour. The culturally rooted, inside-out understanding of healing as reconnection with authentic self, family, and community was our alternative to the dominant approach, which we believe sees healing mostly as alleviating physical and observable symptoms – an approach analogous to turning off a smoke alarm to extinguish a fire. Applied originally to high-risk Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano male youth, LCC has since been extended as an effective tool for youth of colour, in general.

Four Valores

LCC defines four core valores (values) underlying behaviour, dignity, respect, love, and trust (Table 10.1). Each value has a central proposition that is effectuated by a target process, which in turn, results in a target outcome. The overarching goal is to re-root the adolescent in these core values so they may serve as medicine.Footnote 6 Jerry Tello articulates the organizing principle of LCC as, “Within the collective Dignity, Respect, Love and Trust of all people exists as the pathway to beautiful harmonious life.” It reflects the idea that all people carry within themselves the medicine necessary to heal from the overwhelming effects of trauma and other forms of violence.

LCC asserts that medicine is embedded in Indigenous culture, in Indigenous knowledge systems, wisdom, music, dance, and especially ritual and ceremony. LCC also asserts that healing is reciprocal: just as people can cause harm to one another, so, too, can an individual’s self-healing facilitate the healing of the people with whom they are in relationship. Unlike Western medicine that views healing as the application of clinical therapies, LCC views healing as a shared cultural experience – it is relational, occurring in our communion with others.

The Medicine Wheel: Mapping the Healing Journey

LCC defines both a structure and a process for healing. The healing process has five stages in which fear and pain are transformed into increased appreciation for the subjective experience of self and others (see Fig. 10.1). The stage model is similar to and includes all of the elements proposed by Prochaska and Velicer (1997) but acknowledges the subjective fear that keeps people from moving, and includes a cultural/spiritual element to which BYMOC more readily respond.

Moreover, the process is cyclical, suggesting that wounds heal slowly and are difficult to eliminate definitively, and that we revisit wounds to understand them from a more adaptive perspective. Indeed, it is by staying in contact with woundedness that people develop compassion and understanding of others. LCC’s version of the medicine wheelFootnote 7 helps us understand the process by which the interaction of acknowledgment, understanding, integration, movement, and interconnectedness contribute to healing. This medicine wheel underlies the LCC curricula, strategies, and interventions.

Conocimiento (Acknowledgment)

Many Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano youth come from families who have experienced generations of racism, discrimination, and oppression. In response, they detach from their connection to themselves, their families, their relationships, and their own behaviours. They may conform to cultural stereotypes of masculinity and femininity or internalize negative images of themselves. The safety and security of the círculo helps them face and overcome tendencies to run, fight or push people away. The consistent and dependable structure of the círculo becomes the container that allows people to feel welcomed, accepted and wanted.

Entendimiento (Understanding)

Once youth are grounded, they begin to resonate with the teachings offered in the circulo. The facilitator, peers and lessons touch their hearts. Youth that are accustomed to survival mode experience the opportunity for reflection, assessment and understanding. They become emotionally engaged, allowing them to discover, rediscover or reaffirm values they carry within themselves. They also learn to appreciate the importance of ceremonial life and understand its use in maintaining wellbeing. In this stage, they also begin giving voice to the cargas (emotional baggage) they carry and to tolerate the discomfort and pain of changing self-destructive thinking and action. In doing so, they begin bonding with others and experience confianza (trust).

Integracion (Integration)

Applying the principle of en lak’ech,Footnote 8 youth learn to pay close attention to the effects of their actions on others. They develop palabra (credible word), being careful that their words are not used to hurt others, being honest with their skills and capacities so that they live up to what they say and do not over-promise or deceive. In this stage of the process, young people start integrating recently discovered regalos (gifts, e.g., skills and abilities), providing a foundation for lives that are self-fulfilling and of service to others. This ability to put things together, to synthesize is the basis of respect and dignity and discovering their sacred purpose.Footnote 9

Movimiento (Movement)

In this stage, young people begin to “move.” They exhibit new behaviours that expose them to their own self-judgment as well as criticism from others. At this stage, youth need support in committing to their new ways of being and expressing themselves. Learning to commit, to have palabra and work when times get tough is a critical step in healing. They need the participation of family and relationships that witness and continue to support the transition. They experience interconnectedness and ganas,Footnote 10 which allows them make sense of their lives.

En Tloque Nahuaque (Interconnected Sacredness)

The final step of the healing process, like all significant accomplishments in life, is an ongoing process and never a destination. When our brother Ri’taka’me embarked on a trip with us, his refrain was always the same, “a ver hasta donde llegamos” (“let’s see how far we get”). Having given voice or expressed the pain of disconnection, re-rooted in the values embedded in culture and transmitted through relationships, youth are better equipped to battle the challenges of daily life and their transition to manhood. In this stage, it is critical that youth continue to strengthen their commitment to healing themselves and their relations. As evidence of our commitment, we invite graduates to be part of our extended kinship network.

La Cultura Cura’s Practice Intervention: El Joven Noble

With La Cultura Cura as the underlying philosophical premise, El Joven Noble is a youth-development, support, and character development program for BYMOC aged 10–24 years. El Joven Noble consists of a 12-week curriculum focused on healing the results of intergenerational trauma and re-rooting young men in their Indigenous values. The program is relationship-based, reconnecting BYMOC to their true potential as jovenes nobles, or noble youth (Fig. 10.2).

Table 10.2 distils NCN’s experience with Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano youth into a program framework, which shows that with cultural disconnection comes an eroded (a) sacred purpose, (b) sense of responsibility, (c) interdependence, (d) development, and (e) enthusiasm. This erosion is mitigated and ultimately reversed by the practical use of mechicano indio rituals, rite of passage ceremonies, and traditional practices. The feedback loop accounts for the cycle of learning and re-learning when addressing issues of development, adverse behaviour and negative thoughts, feelings, and perceptions among Latinx, Mexican American, and Chicano youth. It does so by putting to practical therapeutic use the nurturing capacity of community elders and family members.

El Joven Noble makes practical use of five teachings in facilitating rites of passage from childhood to manhood, positing that their erosion aggravates personal, family, and community dysfunction. Table 10.2 outlines the five teachings that guide a noble youth—sacred purpose, sense of responsibility, interdependence, development, and enthusiasm. Each teaching has a proposition that is effectuated by a target process and results in a target outcome.

El Joven Noble and Círculo

Tello and NCN staff adapted the universal practice of sitting in circle (circulo) to eat, talk, celebrate, and mourn life as a tool for healing young men, women, and families. Each círculo session revolves around a specific Indigenous knowledge-based teaching. The teaching refers to one or more specific values, such as respect, accountability, and palabra (credible word). In addition, the teaching may have an associated manualidadFootnote 11 or craft that engages and reinforces the teaching. In each session, participants are provided the opportunity to check-in and acknowledge their current reality, as well as the challenges and accomplishments they are facing. In Indigenous ways, this process of sitting, being present and listening to others, is a way of honouring them. Through speaking aloud, participants share and release physical/spiritual baggage, and connect with others. Experience and research tell us that active, non-judging listening is an important skill in the development of empathy among youth (Jones et al., 2019). This is used in all círculo sessions, whether to check-in or to reflect on teachings. Each círculo series ends with a formal celebration, attended by participant relatives and significant others that witness, validate and help reinforce the participant’s commitments.

Facilitators and Training

While the culturally rooted curriculum provides a context and engages youth, the role of facilitators as supportive and caring guides cannot be underestimated. The training is open to all, but usually attracts people in the “helping professions,” such as counsellors, therapists, educators, probation officers. Joven Noble was originally designed for young men, and we’ve found that young men from similar backgrounds as participants are the best “fit,” but gender is not a deterrent. What’s more important is that facilitators commit to “walking the talk” – to living the values they teach. Potential facilitators undergo a highly interactive and rigorous three-day training, conducted in círculo format. A ten-item “healing-informed skills” scale in development is used to assess the facilitators’ comfort with questions such as listening without explaining, sharing from their own experience, dealing with participants that digress from the process, dealing with the spiritual aspects of the círculo, feeling emotional during sessions, or creating a space where people feel encouraged to share.

Trained facilitators are invited and encouraged to join the NCN kinship network, where they can continue learning from others, and share their gifts and find support when needed, and they are encouraged to maintain contact for technical assistance. In an informal follow-up study of 130 people trained in all NCN curricula during the last 6 months of 2019 immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that facilitators ranged in age from 23 to 69, with an average age of 43. They represented 113 zip codes across nine (9) American states.

Figure 10.3 abstracts this dialogue-based, culturally rooted therapeutic process in a Theory of Change. It is defined by the idea that young men need other men, their family, and community to prepare for manhood. As a rites of passage program, El Joven Noble takes account the quality of an adolescent’s bond with his relations, the strength of his ethnic identity, and his self-efficacy in applying positive Indigenous-based masculinity ideals to his transition from childhood to manhood– (1) palabra (credible word), (2) not bringing harm to others, (3) taking responsibility for self and others in his circle, and (4) making time to reflect, prayer and ceremony (5) being a positive example. Figure 10.4 illustrates how the two interventions in Fig. 10.3 lead to the expected outcomes.

Evidence of Program Efficacy

NCN has been conducting in person círculos, training facilitators, building capacity and providing technical assistance since 1988. In addition to our internal evaluation, much of the work has been assessed and highlighted in other reports such as those cited below. We should also note that beginning in March 2020, NCN like many organizations adapted their work to meet COVID-19 restrictions. This was especially significant for us because our indigenous-based practices promoted the importance of physical space, respect for the elements, face-to-face contact and interaction. Maintaining the spirit of our work in a virtual format was challenging, but we did our best, le hicimos la lucha. Many of collaborators, especially Native peoples patiently wait for a return to “normal.”

Some participants, especially those that experienced the face-to-face format, noted the difference between those and virtual círculos. A few others have noted that the virtual format actually helps those people that would be reluctant to share in person. At best, we have very preliminary feedback in both directions and not enough experience with both formats to offer a more informed assessment the effectiveness of virtual círculos.

Recent projects include a five-year collaboration with Race Forward that was funded by the California Endowment. NCN provided in-person training and technical assistance to 140 institutional policy makers and practitioners in Salinas, California in response to a rash of violence and police shootings of several people of colour. The interventions were part of a larger effort for making meaningful change between residents and the institutions that serve them. A project report by Bradshaw-Dieng et al. (2016) found this quote by the mayor of Salinas City poignant to add: “[the city manager] referred to [NCN’s work] as diversity, and I said no, this is different. This is a new framework. We are making a shift.” As part of that shift, Motivating Individual Leadership for Public Advancement (MILPA) and Building Health Communities (BHC) led a campaign under this framework to get the Monterey County board of supervisors to unanimously approve reducing the beds in a newly planned juvenile hall from 150 to 120.

In addition to wide acceptance by community-based organizations and juvenile justice departments, NCN has worked with public and private school systems nationally in southern California, northern California, Maryland, and Texas, to operationalize LCC into the education field. Several of these partners have become anchor organizations that have either institutionalized El Joven Noble or continued to train facilitators on a regular basis.

In 2017, NCN provided training and technical assistance on El Joven Noble, Circle Keeping for educators in the Coachella Unified School District in southern California. Between 2018 and 2019, El Joven Noble prepared youth to conduct a Youth Participatory Action Project (YPAR) in three communities: San Jose and San Diego in California, and Denver, Colorado.

Between December 2017 and January 2018, NCN provided training for 64 service providers as part of a larger projected implemented by the Gang Reduction Office of Los Angeles, California. The services included El Joven Noble sessions for 64 attendees and follow-up Circle Keeper training for 31 of those participants. Program evaluation of the in-person work reflected positive feedback, prompting the project manager to note:

I think that when it comes to NCN, a lot of the agency personnel really liked their training a lot. It resonated with them in many ways. Not to the point where people felt equipped to start their own circles, but it was something that they did find useful, so I think we did start the process of our service providers starting their own healing, so a few of them will go to their own circle on their own time, and that’s a step in the right direction.

Empirical Evidence of Program Efficacy

To date, NCN has conducted Circle Keeper/facilitator trainings in over 40 cities. Follow-up with facilitators trained in 2019, immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, indicated that 74% went on to implement at least one círculo for a total of 5460 participants. While we assist and consult with projects that implement NCN, we rely heavily on external evaluations, as alluded to above. In addition to this validation, we also assess our success using what people tell us in their own words. While tedious and time consuming, these methods are more consistent with our culture-based approach. The data presented below were collected from a sample of eight students that participated in a virtual version of El Joven Noble between 2018 and 2019 at a San Jose high school. All respondents identified as male, ranging from 18 to 22 years in age.

Círculo Experience

A few respondents noted that the círculo helped them manage pandemic-related stress from isolation. One noted that the virtual experience was not the same as the in-person experience. He noted that for him, the “intimacy” was not the same, but the “idea and concept” was nonetheless present and overall helpful. The same responded also liked the “virtual” format, indicating that it allows people to “show their true selves.” The virtual format helps participants feel less “judged,” less “shy” and open to talking. Another participant differentiated between his experience with the círculo and on-line school sessions. He found the círculo much more enjoyable than school.

Acceptance; You are a Blessing

One young man described the círculo as “open arms,” and “welcomed by people that I didn’t even know.” Another participant noted the círculo was:

[A]bout trust and honouring people that are there for you. I never really had that. I didn’t trust nobody and didn’t want to talk to nobody. But when I started going to the circle that’s the main thing that I took away from there, was to start trusting people and to start having respect for the people that love me.

Another respondent offered that the círculo helped him manage the stress that he attributed to the isolation and the pandemic. Another learned the importance of “being honest” and “respectful to others.”

Confianza/Trust

A common theme that emerged from the interviews was confianza/trust in who they were, perhaps less willing to follow along with others, but to lead. One respondent noted that he learned quite a bit about public speaking, suggesting a greater sense of competency and confidence. He expressed gratitude to the círculo facilitators. Another young man told us that the círculo helped him:

[S]ee things as more valuable, like trust and respect, because trust is needed now between one person to another because of what’s happening with the virus. People need to trust one another and tell people who they are, they need to respect the person’s boundaries, the limits, also responsibility of who you are. I would say I am better overall. I am not as mischievous as I use to be, and I don’t look for trouble like I use to. I know that there [are] better things out there. With my friends I kind of overlooked them, I stepped away from them, I kinda knew how they were, I follow my own thing now. I am not so much a follower now; more so a leader now.

Relationships and Respect

The importance of relationship, while not always mentioned directly by the young men is evident throughout the responses. One participant noted that he was impressed with how the maestros, (teacher) or in this case círculo facilitators treated participants with respect. This modelling helped him adopt a “more respectful attitude toward others.” One young man detailed how his relationship with facilitators and group experience helped him change his relationship with his mother:

Yeah, with my mom, me and her didn’t have a good connection, she disowned me when I was 13, and I really didn’t have no respect for her. But when I started going to the circle and started talking to Ariel, Mickey, and people that ran the circle, I actually opened up to them and it just taught me to look at her shoes and I went over to my moms and told her I was sorry, and she said sorry. Now we have a good connection and more than it was. I relate to my parents. I respect them, I treat them like I want to be treated, in a good way. My uncle, he’s going through a class, he’s changed a lot, and I changed a lot during this class and he’s changing more during the period he’s taken the class. I really relate to him.

Interconnection

Relatedly, another participant was particularly impacted by the concept of en lak’ech. Translated from the Mayan as “you are my other me,” this common greeting between people emphasizes the importance of acceptance, compassion and empathy. For example. One young man noted the importance of words – what one says. The lesson he learned was that “what I say actually hurts people and that sometimes people work hard for some things that other people don’t have, and [that] makes them feel that they are guilty of something I have not done yet, and makes me want to learn more about it.”

One of the young men responded on romantic relationships, noting that:

[I]t doesn’t matter who you get, if you get someone, you should love them for who they are, not for what you want them to be. Yes definitely, it brought me insight to my own personal values especially with family and friends, like being kind and understanding of others, and like for example one of the biggest one is maintaining and keeping healthy relationships. With not just boyfriends and girlfriends, but with family and friends and co-workers. I felt the whole group was moving on even if a person joined the call late or missed it, the next call we would make him feel like he was in that (missed) class. That’s what’s good about the class, we didn’t leave anybody behind, if someone missed the class, we made them feel like they were actually in the class, which felt great.

Changing Values and Enduring Change

In addition to changing behaviours and attitudes, respondents were asked if their participation resulted in changes in their personal values. Their responses strongly suggest that the participant’s experience in the círculo, especially their interactions with facilitators and peers generalized to values with respect to family, school and peers. One participant made this connection in this way:

Family is important. It definitely got stronger through círculo. The way I think of them is that they are one big family, you can always come to them for anything you need or anyone you want to talk to. They are always there for you. That is the same like my family and your family, you always have their support and that is why I look at it like that.

A second young man highlighted a profound change in what he considered important:

They really changed things a lot. It made me rethink my whole system, reset the way I do things. I value more what my parents have done, what my family is going through. I really appreciate what they are doing to get me to a better future. Before this class I would be a person who would make hate speech and comments, but now, during the class I see ways in a different way, and a different point of view. I see a lot of things I shouldn’t have said, a lot of things I regret. When I would be with my friends before the virus came in, I would be a disrespectful person, untrustworthy. Now I feel more better, a trustworthy person, a person of confianza.

Discussion

The theoretical and practice formulations behind LCC and El Joven Noble have implications for practice, policy, and research in health and youth development disciplines. In clinical practice, they demonstrate the efficacy of culturally rooted and value-based interventions. In policy practice, their ability to extract the salutogenic value of ancestral teachings enables agency-level policy change to advance the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in our formulations of wellness more widely. In research, they promote inclusiveness when weighing the types of reality that could exist and be retold about BMYOC and their communities.

Practice Implications

LCC and El Joven Noble enhance behavioural health practice among BYMOC by showing the utility of culturally rooted and value-based interventions in engaging BYMOC to a degree that conventional Western clinical interventions have not been documented to do. Their use of Indigenous mechicano indio core values transform the cultural identity and worldview of youth participants instead of simply reframing cognition of high-risk behaviour. By promoting intrinsic self-reform as such, LCC and El Joven Noble show that it is beneficial to promote an individual’s connection to his cultural heritage via values-oriented teachings. By applying the mechicano indio knowledge system as a practical tool in soothing adolescence stress, LCC and El Joven Noble help practitioners rethink what knowledge systems could be included in practitioner training and service delivery.

Furthermore, LCC and El Joven Noble show that respecting the subjective personal and community-level reality of pain and fear in which BYMOC live could effectively move them toward wellness. BYMOC populations use different words and alternative perspectives to describe their subjective experience of the world; thus, mechicano indio knowledge and practices that acknowledge that subjectivity succeed in youth engagement because they facilitate greater understanding of Latinx, Chicano, Mexican American and Native youth.

Policy Implications

LCC and El Joven Noble widen options for agency-level policy change, particularly those impacting the design of behavioural health programming for BYMOC. That the mechicano indio knowledge system is not integrated into the Western medical model serves as an opportunity for agency-level policymaking to allow its wider use. LCC demonstrates how ancestral culture and values could be integrated into our formulations of wellness. Furthermore, by making it plausible that behavioural health programs based on Indigenous knowledge could be eligible for third-party health insurance reimbursement, we have an opportunity to redefine how we compensate for healthcare in the era of value-based versus fee-for-service-based care.

Research Implications

LCC has implications for evaluation research, particularly for Indigenous knowledge-based interventions. Conventional approaches to evaluation research are not reliably respectful of Indigenous communities and the original words of Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous youth. Western evaluators’ effort to aggregate responses into Western themes impose the supremacy of the Western approach to rationality, effacing non-Western worldviews.

LCC promotes the use of a culturally rooted evaluation approach, enabling evaluation research to convey the reality experienced by Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous youth more fully. It does so by describing and explaining that reality more specifically and in a much more balanced way – improving trust between researchers, evaluators, and communities. This, in turn, leads to more valid and meaningful data from our experience, thus, more effective service delivery models, for Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous youth. By delivering access to subjective reality, LCC reduces the power imbalance between Western and non-Western views on what types of reality could exist (ontology) and the ways in which we could know reality (epistemology); therefore, in this chapter, we present the words of participants and public officials to show that evaluators who carefully listen are those who respectfully bridge voices of those that tell the stories and those that can make a difference.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LCC and El Joven Noble’s use of Indigenous knowledge as the source for program theory and traditional rituals for process theory are effective practical uses of the therapeutic and salutogenic value of ancestral teachings. As culturally rooted and value-based interventions, LCC and El Joven Noble deepen intergenerational connectedness and an authentic cultural identity. They soothe adolescent stress and intergenerational trauma among BYMOC in the U.S. using ancestral mechicano indio teachings. They advance the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in the conceptualization of health and wellbeing for BYMOC. Finally, LCC and El Joven Noble inform how we could heal BYMOC, particularly Latinx, Mexican American, Chicano, and Indigenous youth, who face the escalation of trauma-inducing anti-Latino, anti-immigrant racism, and catastrophic encounters with police and the justice system in the U.S.

Notes

- 1.

Ri’taka’meh, a medicine man, was from a small community in the Sierra Madre Occidental. His “traditions” were handed down to him for his people. He shared them with us te’wari (outsiders) reluctantly and fully aware of his transgression. We are forever indebted to him and his family. Out of respect for him and his people, we share his Indigenous name only.

- 2.

People often associate the Méxica or Aztecs as representative of Meso-American culture and thought. While their contributions were undoubtedly important, many philosophical concepts have been traced back to and perhaps beyond the Olmeca, often considered the Mother Culture of Mexico. Many of the concepts we utilize are common from the Ra’ramuri and Yaqui of the north, Wirrarika and as far down as the Quiche people of the Yucatan.

- 3.

Duality is perhaps the most common theme in Indigenous, Meso-American philosophy. Examples of this are found in the Popul Vu, sacred book of the Maya narrates the exploits of the sacred twins as they recover the bones of their ancestors. Among the Tolteca, Quetzalcoatl was at once an actual person and title conferred to one that had integrated earth and sky, represented by a plumed serpent with a head at both ends. The main deity in the Nahua pantheon was Ometeotl, which translates very roughly as Two God.

- 4.

Susto literally translates as “fright” into English. It is often dismissed as a culture-bound condition, specific to Mexico and other Central American countries. While it is often dismissed, a careful study of the physical symptomology reveals that it is a different culturally rooted understanding of a condition very similar to PTSD. The condition is similar to other Indigenous formulations around the world. We recognize it as a valid and legitimate condition that has been devalued by researchers and practitioners with cursory understandings of its origins and associated practices.

- 5.

Sometimes seen as En Tloque Nahuaque, Tloque Nahuaque is from Nahuatl, one of the major Indigenous languages spoken by the people of Central Mexico. There is considerable debate as to the precise meaning of the term. Suggested possibilities include “the lord of the near and the nigh,” that which is far and that which is close or to one side. Others argue it is a name that refers to Mexica deities such as Ometeotl or Tezcatlipoca or an epithet that conveys the omnipresence of the ultimate deity.

- 6.

The term medicine is commonly used in Native American and other Indigenous conceptions of health. According to Merriam-Webster, the term has Latin origins and therefore calls for some discussion. According to most sources, medicine refers to treatment with great care and skill. It refers to the treatment and not so much a substance, as commonly understood in conventional language.

- 7.

While the colours, associated animals, symbols and even direction of movement may vary, the medicine wheel is common to virtually all Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Formed by the path of the sun across the surface of the earth, it can serve as an orienting tool that guides our movement through life.

- 8.

En lak’ech is a greeting from the Mayan Language that has gained widespread popularity of late. Literally, it translates as “you are my other me.” LCC uses the term to promote interconnectedness, respect and affection between people.

- 9.

A thorough discussion of the term “sacred” would take volumes and well beyond our scope. We respectfully offer the following definition: “Sacred refers to that which us set apart, cannot be completely understood nor explained and related with the ultimate source of life.”

- 10.

Ganas is a common term used in Mexican Spanish. It refers to both the willingness and energy to move – to accomplish something.

- 11.

Manualidad is a common term for a handicraft. The hand in Meso-American culture is the instrument through which we express the intentions of our heart. Manualidades result in hand made concrete outcomes, something participants can take pride in making.

References

Andrade, N., Ford, A. D., & Alvarez, C. (2020). Discrimination and Latino health: A systematic review of risk and resilience. Hispanic Health Care International, 1540415320921489.

Ardino, V. (2012). Offending behaviour: The role of trauma and PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18968

Bradshaw-Dieng, J., Valenzuela, J., & Ortiz, T. (2016). Building the we; healing informed governing for racial equity in Salinas. Race Forward, The Center for Racial Innovation.

Brave Heart, M., Chase, E., & J., Altschul, D.B. (2011). Historical trauma among indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628913

Cabrera, N., & Hennigar, A. (2019). The early home environment of Latino children: A research synthesis. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/the-early-home-environment-of-latino-children-a-research-synthesis

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2003). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Cerdeña, J. P., Rivera, L. M., & Spak, J. M. (2021). Intergenerational trauma in Latinxs: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113662.

Coll, K., Freeman, B., Robertson, P., Cloud, E., Cloud Two Dog, E., & Two Dogs, R. (2012). Exploring Irish multigenerational trauma and its healing: Lessons from the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). Advances in Applied Sociology, 2, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.22013

Dragomir, R. R., & Tadros, E. (2020). Exploring the impacts of racial disparity within the American juvenile justice system. Juvenile & Family Court Journal, 71, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12165

Gibson, L. E., Holt, J. C., Fondacaro, K. M., Tang, T. S., Powell, T. A., & Turbitt, E. L. (1999). An examination of antecedent traumas and psychiatric comorbidity among male inmates with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 473–484.

Gonzales, N. A., Dumka, L. E., Millsap, R. E., Gottschall, A., McClain, D. B., Wong, J. J., Germán, M., Mauricio, A. M., Wheeler, L., Carpentier, F. D., & Kim, S. Y. (2012). Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026063

Gonzales, N. A., Dumka, L. E., Millsap, R. E., Gottschall, A., McClain, D. B., Wong, J. J., Germán, M., Mauricio, A. M., Gonzalez, L. M., Mejia, Y., Kulish, A., Stein, G. L., Kiang, L., Fitzgerald, D., & Cavanaugh, A. (2020). Alternate approaches to coping in Latinx adolescents from immigrant families. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(3), 353–377.

Graham, P. W., Yaros, A., Lowe, A., et al. (2017). Nurturing environments for boys and men of colour with trauma exposure. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review, 20, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0241-6

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, and cultures. McGraw-Hill.

Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., Furness, T., & Foster, K. (2019). Preventing intergenerational trauma transmission: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(7–8), 1100–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14735

Jeffers, J. L. (2019). Justice is not blind: Disproportionate incarceration rate of people of colour. Public Health, 34(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1562404

Jones, S. M., Bodie, G. D., & Hughes, S. D. (2019). The impact of mindfulness on empathy, active listening, and perceived provisions of emotional support. Communication Research, 46(6), 838–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215626983

Kluckhohn, F. R., & Strodtbeck, F. L. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Row, Peterson.

Koch, A., Brierley, C., Maslin, M., & Lewis, S. (2019). European colonization of the Americas killed 10 percent of world population and caused global cooling. The Globe, Retrieved from https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-01-31/european-colonization-americas-killed-10-percent-world-population-and-caused.

Kovera, M. B. (2019). Racial disparities in the criminal justice system: Prevalence, causes, and a search for solutions. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1139–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12355

Maschi, T., Bradley, C. A., & Morgen, K. (2008). Unraveling the link between trauma and delinquency: The mediating role of negative affect and delinquent peer exposure. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 6(2), 136–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204007305527

Orozco-Figueroa, A. (2021). The historical trauma and resilience of individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A scoping literature review and emerging conceptual framework. Genealogy, 5, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5020032

Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behaviour change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

Santiago, C. D., Distel, L. M. L., Ros, A. M., et al. (2018). Mental health among Mexican-origin immigrant families: The roles of cumulative sociodemographic risk and immigrant-related stress. Race & Social Problems, 10(3), 235–247.

Spitzer, C., Dudeck, M., Liss, H., Orlob, S., Gillner, M., & Freyberger, H. J. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder in forensic inpatients. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 12(1), 63–77.

Tello, J. T. (2018). Recovering your sacredness. Sueños Publications.

Vanden WallBake, R. V. (2013). Considering childhood trauma in the juvenile justice system: Guidance for attorneys and judges. American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_interest/child_law/resources/child_law_practiceonline/child_law_practice/vol_32/november-2013/considering-childhood-trauma-in-the-juvenile-justice-system – gui/

Williams, M. T., Peña, A., & Mier-Chairez, J. (2017). Tools for assessing racism-related stress and trauma among Latinos. In L. Benuto (Ed.), Toolkit for counseling Spanish-speaking clients (pp. 71–95). Springer.

Wolff, N. L., & Shi, J. (2010). Trauma and incarcerated persons. In C. L. Scott (Ed.), Handbook of correctional mental health (pp. 277–320). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Escamilla, H., Vergara, R.B., Tello, J., Sánchez-Flores, H. (2023). La Cultura Cura and El Joven Noble: Culturally Rooted Theory and Practice Formulations for Healing Wounded Boys and Young Men of Colour in the United States. In: Smith, J.A., Watkins, D.C., Griffith, D.M. (eds) Health Promotion with Adolescent Boys and Young Men of Colour. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22174-3_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22174-3_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-22173-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-22174-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)