Overview

This chapter explores simulation design in the field of teacher education. Simulation creation is used as a vehicle for collaborative planning and professional learning in which future secondary school teachers in a postgraduate course learn about simulation in an EFL/ESL context and work in small groups to design a simulation scenario and its profiles. The flexible nature of simulation allows the pedagogical integration of other methodologies. In this study, flipped classroom and learning stations are used. The case study of 2 consecutive years reports the participants’ perceptions about the potential of simulation to open a dialogic space where they can share ideas and consolidate learning. The objective pursued is to provide future teachers the opportunity to gain greater awareness of teaching and learning process by participating in and later creating a simulation. Thus, they become more effectively acquainted with active methodologies practices. A joint design of simulation is presented as a way to introduce simulations in foreign language classes in secondary education.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, the reader should be able to:

-

identify the potential of simulation from a collaborative perspective in teacher training;

-

understand the value of simulation as a methodology to enhance dialogic learning;

-

comprehend the concatenated functioning of active methodologies;

-

identify some pitfalls of EFL/ESL instruction in secondary school through the future teachers’ comments.

1 Introduction

Teacher education has experienced significant changes in Europe. Traditionally, teacher training has been perceived to be the sole responsibility of universities. However, the demands for highly qualified and versatile teachers, in accordance with the Bologna Declaration (1999), call for the development of curriculum design inspired by deep-learning principles. Deep learning promotes the qualities and competences teachers need by building complex understanding and meaning rather than focusing on accumulative knowledge that can today be gleaned through search engines, as the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) clearly states. This context justifies the need for a methodological change in teaching practices. Today’s teachers need to be trained to try learning methodologies themselves, compare and contrast the methodological fundamentals and their implementation, and design integrative proposals for classroom intervention. Simulation in this study is used as a journey future teachers undertake to develop teaching competences from experimentation to simulation creation.

Although it is true that there is a relatively short tradition of simulation in teacher preparation (Flanagan & Nestel, 2004 in Al-Elq, 2010), there is already sufficient literature about the great potential of simulation in the development of professional competences: dialogic learning, teamwork, negotiation, decision-making, and the development of interpersonal relationships (Asal & Blake, 2006; Blum & Scherer, 2007; Ekker, 2004; Ekker & Sutherland, 2009; Sutherland, 2000, 2002, among others).

Simulations create a complete environment within which students interact to apply previous knowledge and practice skills related to their discipline. Simulations also serve as models for teachers to demonstrate the integration of different methodologies as they move from the briefing phase (flipped classroom, task-based learning, webquests, class debate...) to the action (simulation) to the debriefing phase (reflective learning, focus group). Through simulation, teachers integrate multiple teaching goals in a single process (Angelini, 2016, 2021; Angelini & García-Carbonell, 2019; Angelini et al., 2015; García-Carbonell, 1998; García-Carbonell & Watts, 2012; García-Carbonell et al., 2001, 2012; Wedig, 2010). Simulations provide opportunities for active participation to develop interactive and communication skills and link knowledge and theory to application (Hertel & Millis, 2002).

The gains of simulation applied to language learning are discussed at length by Crookall and Oxford (1990) and García-Carbonell et al. (2001). Advantages include the immersion in language learning through meaningful situations, immediate feedback through teamwork, constant interaction, and lower anxiety. Empirical research conducted by Angelini (2012), Angelini and García-Carbonell (2019), García-Carbonell (1998), García-Carbonell and Watts (2012), García-Carbonell et al. (2001), and Rising (1999, 2009) supports the effectiveness of simulations in the development of communicative competence in English as a foreign language (EFL).

For example, there is qualitative research based on students’ perceptions after a telematic simulation. Watts et al. (2011) found that students’ motivation increased during the simulation and that their interpersonal skills were reinforced. Andreu-Andrés and García-Casas (2011) found that students had fun while learning. Woodhouse (2011) demonstrated that a computer-assisted simulation greatly helped EFL students to consolidate linguistic structures as well as professional skills such as negotiating, decision-making, and working collaboratively. Angelini and García-Carbonell (2014) also corroborated the effectiveness of simulation and gaming in improving oral proficiency in EFL along with the development of student responsibility and the generic skills mentioned above. Thus, in light of the virtues that simulations have to offer in teacher education, this study poses the following research question:

Research Question: Can the creation of simulation scenarios be an effective way to introduce simulations as a classroom technique?

2 Methodological Integration

Future teachers of a postgraduate course on teaching methodologies are presented with a simulation scenario to analyze. They follow the conventional procedure: a briefing phase in which the scenario is studied and the problems are identified. Teams of five members are created and profiles are assigned. The teams go through the simulation phase to deal with the several challenges presented and try to find thorough solutions in light of the research they have previously conducted in the briefing phase. Debriefing unfolds as expected, first intra-group reflections on their involvement and participation, their learning and perceptions. So far, future teachers have experienced simulation by doing it themselves. The shift in the proposal comes when these future teachers are now asked to create their own simulation scenarios and profiles to be applied to secondary school students.

Following the flipped classroom model, future teachers are first presented with specific literature on simulation. By flipping the classroom, we invert the traditional teacher-centered method, delivering instruction online outside of class time and bringing simulation discussion into the classroom (Strayer, 2007, 2012; Tourón et al., 2014; Tucker, 2012). In this way, the flipped model uses educational technology to deliver theory and background materials and serves to promote class time economy.

2.1 Flipped Learning and Classroom Dynamics

It is important to identify the main pillars flipped learning relies on to be able to apply it properly. According to the Flipped Learning Network30, to engage in the flipped model, teachers must incorporate a flexible environment in and out of class, a learning culture, intentional content, and professionalism.

Creating a flexible environment involves rearranging the classroom design. In our case, there are four learning spaces or corners, in which future teachers in teams deal with different tasks.

As our main interest is to introduce simulation as a teaching strategy to enhance English learning, the classroom learning corners delve into discussion meeting points:

-

(a)

briefing: how can you engage your students to participate in a simulation? What aspects would you need to consider before presenting the scenario? Would you flip the classes to introduce some content related to the scenario? How would you make sure your students are sufficiently prepared to carry out the action? What criteria would you follow to make the teams?

-

(b)

action: What is your role as a facilitator of the simulation? What aspects should you consider when facilitating? What norms would you remind yourself and your students to consider? How would note-taking be conducted? Would you record the students?

-

(c)

debriefing: How would you go about the reflection? How would you share your facilitation notes? How would your comments and questions be conducive to reinforce learning?

-

(d)

simulation creation: Bearing in mind your students in the practice school, create a simulation adapted to the students’ interests, learning outcomes, and English level. Pay special attention to all the simulation phases.

By setting our future teachers this challenge, we provide more flexible and individualized instruction as we offer the opportunity for adequate tutorial guidance and scaffolding material in smaller groups. Thus, the flipped model helps maximize each learner’s potential for success, as teachers can move around the classroom, approach individual learners, and identify learning styles, interests, abilities, and difficulties to provide differentiated instruction (Fuller, 2015; Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990; Jonassen & Grabowski, 2012; Mazur et al., 2015).

In addition, another flipped learning pillar is the learning culture. Our future teachers demonstrate commitment in the construction of knowledge. They gain autonomy by doing research on simulation outside of the class, so this instructional shift from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered approach provides more opportunities to deal with a variety of topics in class and create a rich learning environment (Bailey et al., 2013; Bergmann et al., 2013).

The implementation of the flipped classroom model demands a high degree of professionalism, as we must provide relevant and individualized feedback, carry out ongoing formative assessment, and guide future teachers on their reflections and proposals (Bergmann et al., 2013; Bergmann & Sams, 2012; Berret, 2012; Musallam, 2014).

3 Materials and Methods

A group of postgraduate students (N = 57) were asked to respond to a classroom-based experience in the official postgraduate course titled ‘Didactic Resources for Teaching EFL and Literature in Secondary Schools’. The data were collected from two consecutive courses.

Following the flipped learning model, future teachers used text and video materials uploaded to the virtual campus to prepare for class sessions. Before creating their simulation, future teachers participated in a simulation themselves. (See simulation in Appendix). Then, in teams of up to 5–6 members, future teachers worked together on the design of complete simulations on common topics dealt with in secondary schools: the use of mobile phones in class, homework, a balanced diet, workout addiction, among others. The ultimate goal was to develop scenarios, profiles, procedural norms, and debriefing instructions. Figure 10.1 describes the procedure followed.

First, the future teachers participate in a complete simulation (Masterminders’ School) to, in Dewey’s words, ‘learn by doing’ (1938). Experiencing the simulation for themselves, the future teachers start to get the gist of the methodology they will later analyze.

Second, after going through all the phases of the simulation themselves, the future teachers are posed with the challenge: ‘create a simulation to be used in secondary school’. As most do not work yet, they are asked to have their placement school in mind to contextualize and adapt the simulation. Their research is two-fold: (a) find information about simulation in EFL, its virtues, its limitations, procedure, tips on facilitation and (b) find possible topics usually studied in the English subject in secondary school. The flipped classroom model is used in which videos and reading materials are consulted from the virtual campus. In class, learning corners are created to go about the four core aspects of research: briefing–action–debriefing–simulation creation.

Third, clear guidelines are provided on how to design a simulation. Future teachers work collaboratively on the simulation creation in same groups as for the ‘Masterminders School’ simulation.

Finally, the future teachers’ simulations are shared with the other groups and they receive feedback from their peers.

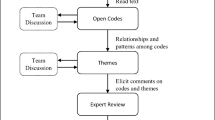

The future teachers reflect on the teaching proposal for the course by responding to the following question in writing: ‘Comment on your experience with simulation as a teaching-learning strategy’. Written responses (N = 57) are uploaded onto the university virtual campus and later extracted for analysis. The study follows a qualitative design that has reached a height, especially in the social sciences, where the role of participants and their perceptions are highlighted by their own discourse (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Goetz & Le Compte, 1988; Harris, 2005; Martínez, 2000; Rodríguez et al., 1996; Sandín Esteban, 2003; Vallés, 1997, 2002). Responses were first classified into initial categories and subcategories until saturation of the data with the aid of Dedoose Version 9.0.17. Finally, the main conceptual categories are defined and interpreted.

4 Results

The future teachers’ responses to ‘Comment on your experience with simulation as a teaching-learning strategy’ yielded three core categories: simulation in teacher education; simulation to enhance communication in English; integration of methodological approaches.

As for the first category, simulation in teacher education, most future teachers indicated the forceful quality of simulation in their degree. The whole subject was built around simulation which eased their understanding of the methodology. As some students reported:

Simulation should have been used in other subjects in our degree. I could feel the challenges from a very practical perspective, placing myself in my students’ shoes. (S3)

Simulation is a powerful strategy for all teachers. There is real practice about communicating with workmates, dealing with serious issues and finding good solutions. (S12)

Students’ comments have contributed to the ratification of two important aspects in teacher education: the importance of experiencing active methodologies in their degrees, some of which they would eventually use with their own students/learners; and the ignored simulation potential in teacher training. Several studies indicate that simulation requires a vast preparation on the part of the facilitator as well as his/her expertise to make the most of the experience (Agllias et al., 2021; Bradshaw et al., 2018, 2021; Pas et al., 2019). In contrast to traditional simulation instruction, in our study, the method emerged from experimentation of a simulation and later research instead of lecturing about simulation. In spite of all the virtues of simulation identified and extensively discussed in this volume, we may assume these might be some of the reasons why simulation is not widely adopted in teacher education programs.

The creation of simulations based on secondary school content material helped future teachers become more critical about the textbooks and material used in EFL lessons.

If I were a student in secondary, I would like English. I don’t see the point of having a book which is expensive and boring. (S17)

I should have learned more English had I done simulations in my classes. (S18)

Now, I feel I can adapt the material students use in the English lessons by creating simulations and communicative exercises. (S34)

In the second category simulation to enhance communication in English, the future teachers found numerous benefits. By using simulation, from simple ones to more demanding in terms of content knowledge and grammatical structures, most of the teachers indicated the need to manage a wider range of language-related skills.

I understand that simulation requires preparation in relation to content and vocabulary. The use of simulations in secondary school will help students learn more English than in conventional lessons. (S9)

Through the simulation, students will be able to use the target language with a clear purpose. They will not be restricted to answer common questions as in Cambridge exams. Instead, they will use their knowledge of a topic to create more knowledge using English as a vehicle for communication. (S33)

At this point, it is important to draw a distinction between simulation to enhance communication in English and simulation to foster English learning. Although these may look like synonymic terms, they are not. What the future teachers are observing is the purposeful nature of simulation in communication. It is not about the accurate use of the English language per se. It is about the need to have something to say about a specific topic. Simulation can become a powerful strategy to gain fluency in a foreign language (Angelini, 2021; Angelini & García-Carbonell, 2019; Crookall & Oxford, 1990; García-Carbonell et al., 2001). As the future teachers participated in a simulation themselves, they could elucidate the dialogic nature of simulation interactions.

The third category ‘integration of methodological approaches’, addresses the flexible nature of simulation. The different phases in the simulation require different methodologies to apply. In our study, we resorted to flipped classroom from a very instrumental perspective. We needed to save class time. So, instead of devoting time to theorize about simulation, we provided the future teachers with recorded and reading material to be prepared before coming to class. In this way, we were able to conduct meaningful discussions leading to the design of their own simulations.

I really learned by watching the videos though I was skeptical at first. Not knowing what to expect from the course made me feel uneasy. However, it was the first lessons and then things ran smoothly. I like the flipped model. I think I’ll use it in the future. (S6)

The classes were far more dynamic than other lessons I have had. I learned from the stations or corners because they had questions that triggered our knowledge about simulation. (S48)

As we can observe, changing methodologies may result ‘uneasy’ for some. However, it is important for facilitators to keep focused and indicate the learning outcomes expected. Working with simulation is like a journey in which students/participants and facilitators embark. There is a procedure to follow, there are many aspects to consider. A solid, rounded briefing will guarantee success in the simulation placement; a well-prepared facilitator will anticipate inconveniences and will work accordingly; a constructive debriefing will help consolidate the learning and will make the experience repeatable.

5 Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to answer the question ‘Can the creation of simulation scenarios be an effective way to introduce simulations as a classroom technique?’. We can argue that some of the findings are conducive to highlighting the value of simulation design in teacher training. The very flexible nature of simulation allows the integration of methodological approaches like the ones implemented in the study: flipped classroom and learning stations. The future teachers’ responses to the open question ‘Comment on your experience with simulation as a teaching-learning strategy’ confirmed the merits of the proposal. Simulation in teacher education is considered necessary to immerse future teachers in educational realities at a low risk and can become a fruitful strategy to promote communication over specific topics. Furthermore, by integrating the flipped learning model, learning station and simulation, we propose to plunge students into dynamics in which they are benefitted not only linguistically but also professionally. Although successive qualitative and quantitative studies over time and a broader sample may increase reliability in the integration of flipped classroom, learning station and simulation in foreign language learning, the results of the present study indicate that the approach can be an effective way to introduce simulation in foreign language classes in secondary education.

References

Agllias, K., Pallas, P., Blakemore, T., & Johnston, L. (2021). Enhancing child protection practice through experience-based simulation learning: The social work big day in. Social Work Education, 40(8), 1024–1037.

Al-Elq, A. H. (2010). Simulation-based medical teaching and learning. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 17, 35–40.

Andreu-Andrés, M. A., & García-Casas, M. (2011). Perceptions of gaming as experiential learning by engineering students. International Journal of Engineering Education, 27, 795–804.

Angelini, M. L. (2012). Simulation and gaming in the development of production skills in English. Doctoral thesis, Department of Applied Linguistics, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain.

Angelini, M. L., & García-Carbonell, A. (2014). Análisis cualitativo sobre la simulación telemática como estrategia para el aprendizaje de lenguas [Qualitative analysis about telematic simulation as a learning strategy of foreign languages]. RIE Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 64(2).

Angelini, M. L., García-Carbonell, A., & Martínez-Alzamora, N. (2015). Estudio cuantitativo discreto sobre la simulación telemática en el aprendizaje del inglés [Discrete quantitative study about telematic simulation in learning EFL]. RIE Revista Iberoamericana De Educación, 69(2), 51–68.

Angelini, M. L. (2016). Integration of the pedagogical models “simulation” and “flipped classroom” in teacher instruction. SAGE Open, 6(1), 2158244016636430.

Angelini, M. L., & García-Carbonell, A. (2019). Developing english speaking skills through simulation-based instruction. Teaching English with Technology, 19(2), 3–20.

Angelini, M. L. (2021). Learning through simulations: Ideas for educational practitioners. Springer Nature

Asal, V., & Blake, E. L. (2006). Creating simulations for political science education. Journal of Political Science Education, 2, 1–18.

Bailey, J., Ellis, S., Schneider, C., & Ark, T. V. (2013). Blended learning implementation guide. http://net.edu-cause.edu/ir/library/pdf/CSD6190.pdf

Bergmann, J., Overmyer, J., & Wilie, B. (2013, July 9). The flipped class: What it is and what is not. http://www.thedailyriff.com/articles/the-flipped-class-conversation-689.php

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom. Reach every student in every class every day. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development & International Society for Technology in Education.

Berret, D. (2012, February 19). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 12, 1–14.

Bologna Declaration. (1999, June 19). Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education. http://www.ehea.info/

Blum, A., & Scherer, A. (2007). What creates engagement? An analysis of student participation in ICONS simulations. APSA Teaching and Learning Conference, Charlotte, NC.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., Pas, E. T., Larson, K. E., & Johnson, S. R. (2018). Coaching teachers in bullying detection and intervention. Springer Nature.

Bradshaw, T., Blakemore, A., Wilson, I., Fitzsimmons, M., Crawford, K., & Mairs, H. (2021). A systematic review of the outcomes of using voice hearing simulation in the education of health care professionals and those in training. Nurse Education Today, 96, 104626.

Crookall, D., & Oxford, R. L. (1990). Simulation, gaming, and language learning. Newbury House.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster.

Ekker, K. (2004). User satisfaction and attitudes towards an internet- based simulation. In Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (pp. 224–232). IADIS Press.

Ekker, K., & Sutherland, J. (2009). Simulation-games as a learning experience: An analysis of learning style. In Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (pp. 247–259). IADIS Press.

Flanagan, B., Nestel, D., & Joseph, M. (2004). Making patient safety the focus: crisis resource management in the undergraduate curriculum. Medical Education, 38(1), 56–66.

Fuller, J. (2015). Investigating a flipped professional learning approach for helping high school teachers effectively integrate technology. In D. Slykhuis & G. Marks (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2015 (pp. 920–924). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

García-Carbonell, A. (1998). Efectividad de la simulación telemática en el aprendizaje del inglés técnico [Effectiveness of telematic simulation in learning technical English] (Doctoral thesis). Universitat de València.

García-Carbonell, A., Rising, B., Watts, F., & Montero, B. (2001). Simulation/gaming and the acquisition of communicative competence in another language. Simulation & Gaming: An International Journal of Theory, Practice and Research, 32, 481–491.

García-Carbonell, A., & Watts, F. (2012). Investigación empírica del aprendizaje con simulación telemática [Empirical research about learning through telematic simulation]. Revista Iberoamericana De Educación, 59, 1–11.

García-Carbonell, A., Watts, F., & Andreu-Andrés, M. A. (2012). Simulación telemática como experiencia de aprendizaje de la lengua inglesa. Revista De Docencia Universitaria, 10, 301–323.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

Goetz, J. P., & Le Compte, M. D. (1988). Etnografía y diseño cualitativo de investigación educativa [Ethnography and qualitative design of educational research]. Morata.

Harris, K. M. D. (2005). Teachers’ perceptions of modular technology education laboratories. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 42(4), 52–70.

Hertel, J. P., & Millis, B. J. (2002). Using simulations to promote learning in higher education: An introduction. Stylus Publishing.

Hiemstra, R., & Sisco, B. (1990). Individualizing instruction: Making learning personal, empowering, and successful. Jossey-Bass.

Jonassen, D. H., & Grabowski, B. L. (2012). Handbook of individual differences, learning, and instruction. Routledge.

Martínez, M. (2000). La Investigación Cualitativo Etnografía en Educación [Ethnographic educational research in education]. Peter Lang.

Mazur, A. D., Brown, B., & Jacobsen, M. (2015). Learning designs using flipped classroom instruction. Canadian Journal of Learning & Technology, 41(2), 1–26.

Musallam, R. (2014, December 10). Should you flip your class-room? http://www.edutopia.org/blog/flipped-classroom-ramsey-musallam#comment-form.

Pas, E. T., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). Coaching teachers to detect, prevent, and respond to bullying using mixed reality simulation: An efficacy study in middle schools. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(1), 58–69.

Rising, B. (1999). La eficacia didáctica de los juegos de simulación por ordenador en el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera en alumnos de Derecho, Económicas e Ingeniería [The effectiveness of telematic simulation games in EFL for Law, Economics, and Engineering] (Doctoral thesis). Universidad Pontificia Comillas.

Rising, B. (2009). Business simulations as a vehicle for language acquisition. In V. Guillén- Nieto, C. Marimón-Llorca, & C. Vargas-Sierra (Eds.), Intercultural business communication and simulation and gaming methodology (pp. 317–354). Peter Lang.

Rodríguez, G., Gil, J., & García, E. (1996). Metodología de la Investigación Cualitativa [Methodology for qualitative research]. Aljibe.

Sandín Esteban, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en Educación [Qualitative research in education]. McGraw-Hill.

Strayer, J. F. (2007). The effects of the classroom flip on the learning environment: A comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a flip classroom that used an intelligent tutoring system (Doctoral dissertation). The Ohio State University.

Strayer, J. F. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learning Environments Research, 15, 171–193.

Sutherland, J. (2000, July 7). Making good things even better: An IDEELiStic approach to telematics simulation. Presentation prepared for ED-MEDIA 2000, Montreal, Québec, Canada. http://www.ideels.uni-bremen.de/.

Sutherland, J. (2002). Value-added multilateral curriculum development: Project IDEELS. http://www.ideels.uni-bremen.de/

Tourón, J., Santiago, R., & Diez, A. (2014). The flipped classroom: Cómo convertir la escuela en un espacio de aprendizaje [The flipped classroom: how to turn school into a learning environment]. Grupo Océano.

Tucker, B. (2012). The flipped classroom. Education Next, 12(1), 82–83.

Vallés, M. (1997). Técnicas cualitativas de investigación social. Reflexión metodológica y práctica profesional [Qualitative techniques of social research. Methodological reflection and professional practice]. Síntesis S.A.

Vallés, M. (2002). Entrevistas Cualitativas [Qualitative interviews] (Cuadernos Metodológicos, 32). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Watts, F., García-Carbonell, A., & Rising, B. (2011). Student perceptions of collaborative work in telematic simulation. Journal of Simulation/gaming for Learning and Development, 1, 1–12.

Wedig, T. (2010). Getting the most from classroom simulations: Strategies for maximizing learning outcomes. Political Science & Politics, 43, 547–555.

Woodhouse, T. J. (2011, March 24–26). Thai university students’ perceptions of simulation for language education. Paper presented at ThaiSim 2011, Ayutthaya, Thailand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Simulation: ‘Masterminders School’

Briefing sheet

Masterminders School provides a learning culture that embraces change and a desire for continual improvement, producing well-rounded individuals with the skills and knowledge for success. Masterminders School encourages the development of enquiring minds and nurtures a love for learning. It develops perseverance and determination to complete challenging tasks. Children are encouraged to learn from their mistakes and think about the consequences of their actions with regard to their work and their behavior. Children are to be able to work in a variety of situations, developing cooperation, empathy, and team spirit. Children actively work with the latest technology and do projects in teams.

Sadly, very recently, two Masterminders pupils have had serious health problems. One of them, Tim (11 years old) has been suffering terrible headaches which made him skip most of the second-semester classes. He is in 6th-Grade Primary. The other pupil is Tiffany. Tiffany is only 15 and has been diagnosed with an unusual insomnia for a young person as she is. In both cases, their parents put the blame on the great exposure to radiation at school.

Here’s an open letter from Tiffany’s mother:

There is a last-minute meeting to deal with these two cases as several parents have begun to worry about this situation which may be damaging pupils’ health. The governing body is also affected as the school project may be jeopardized.

The Governing Bodies attend the meeting:

-

1.

HEAD OF SCHOOL: Runs the school and is in charge of strategic developments for the school and receives reports from the Head teachers. The HEAD OF SCHOOL strongly support technology and educational innovation and is HEAD PARENT 1’s friend.

-

2.

HEAD TEACHER 1: Specialist in charge of 5th Grade and does not like technology very much. She/he needs the job to support the family.

-

3.

HEAD TEACHER 2: Specialist in charge of 6th Grade. Very ambitious. Would like to become the Head of the school in two years-election.

-

4.

HEAD PARENT 1: Representative of the MASTERMINDERS PARENT GROUP and Helen Miles’ closest friend (Tiffany’s mother).

-

5.

HEAD PARENT 2: Former MASTERMINDERS’ pupil. Loves the school.

-

6.

FOMS: Friends of Masterminders School. FOMS’ mission is to raise funds to allow the school to have the things that the budget won't (allow) stretch to. But it is not only about money but also wants to create a sense of community and have some fun. FOMS have economic agreements with Apprit, the Company that has sponsored the families with free aPads (tablets). However, they fear their children suffer from similar effects as Tim and Tiffany.

Objectives

-

1.

To ban WiFi from school?

-

2.

To keep or ban school project?

-

3.

To get money in compensation for health problems?

An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

Profiles

Head of School

Head Teacher 1

Head Teacher 2 Head Parent 1

FOMS Member

Head Parent 2.

Time Allotted

Background study: 20 min; Action: 30–40 min

Profile 1—HEAD OF SCHOOL

OBJECTIVE

To convince the rest of the Governing Body to continue with the school projects, which require pupils operating electronic devices. Masterminders School is a leading institution for its innovation program and receives each year several grants from the regional educational department.

An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

BACKGROUND

You are the HEAD OF SCHOOL. You run the school and are in charge of the school’s strategic developments. You strongly support the use of technology and educational innovations. Your school gets quite a lot of economic support to carry out the projects, which require the use of electronic devices. You are HEAD PARENT 1’s friend.

Profile 2—HEAD TEACHER 1 OBJECTIVE

To ban WiFi and ICT projects.

An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

BACKGROUND

You are the HEAD TEACHER 1, specialist in charge of 5th Grade. You do not like technology very much. In fact, you also suffer from headaches while you are at school and use medication. You are afraid you might be dismissed if you do not support the school’s initiative. You want to ban WiFi but you need the job to support the family.

Profile 3—HEAD TEACHER 2 OBJECTIVE

To show you are a decision-maker and a very good candidate for running the institution in 2 years.

BACKGROUND

You are HEAD TEACHER 2, specialist in charge of 6th Grade. You are very ambitious. You do not care much about education. You are in fact rather tired of the monotonous job and would like to become the HEAD OF SCHOOL in 2 years election. You will do whatever necessary to finally get it. You know you need the support of the actual HEAD OF SCHOOL. However, parents have a very strong voting decision.

Profile 4—HEAD PARENT 1 OBJECTIVE

To mediate between the Head of the school’s strong position and parents’ complaints about the exposure to radiation.

An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

BACKGROUND

You are HEAD PARENT 1: Representative of the MASTERMINDERS PARENT GROUP and Helen Miles’ closest friend (Tiffany’s mother). As a parent, you want the best type of education for your two children. As Helen’s friend, you firmly believe that Tiffany has been seriously affected by the continuous exposure to radiation at school.

(Profile 5—HEAD PARENT 2) Extra OBJECTIVE

To have the best-ranked school in the region.

BACKGROUND

You are HEAD PARENT 2, a former MASTERMINDERS’ pupil. You love the school. Your only child is about to graduate next semester.

Profile 6—FOMS Representative OBJECTIVE

To continue receiving funds from Apprit. An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

BACKGROUND

You are a FOM’s member. As you know, FOM’s mission is to raise funds to allow the school to have the things that the budget won't stretch to! FOMS also wants to create a sense of community and have some fun! It organizes events for the families. FOMS have economic agreements with Apprit, the Company which has given all the families’ aPads for free.

However, you know that most FOM’s members fear their children suffer in the future from similar effects as Tim and Tiffany.

Facilitation’s Notes

-

Materials Needed: None

-

Simulation Type: Closed, realistic

-

Time Allotted: Background study 20 min—Action 30–40 min

-

Number of Participants: five to six per group [multiple groups can participate at the same time]

GOAL:

This is a group activity that challenges and tests participants’ innovation competences, in order to identify the skills and capacities shown in individual, and interpersonal dimensions.

PROFILE ROLES:

-

1.

HEAD OF SCHOOL: Runs the school and is in charge of strategic developments for the school and receives reports from the Headteachers. The HEAD OF SCHOOL strongly supports technology and educational innovation and is HEAD PARENT 1’s friend.

-

2.

HEAD TEACHER 1: Specialist in charge of 5th Grade and does not like technology very much. She/he needs the job to support the family.

-

3.

HEAD TEACHER 2: Specialist in charge of 6th Grade. Very ambitious. Would like to become the HEAD OF SCHOOL in 2 years election.

-

4.

HEAD PARENT 1: Representative of the MASTERMINDERS PARENT GROUP and Helen Miles’ closest friend (Tiffany’s mother).

-

5.

HEAD PARENT 2: Former MASTERMINDERS’ pupil. Loves the school.

-

6.

FOMS: Friends of Masterminders School. FOMS’ mission is to raise funds to allow the school to have the things that the budget won't stretch to! But it is not only about money, FOMS also want to create a sense of community and have some fun! FOMS have economic agreements with Apprit, the Company which has given all the families’ aPads for free. However, they fear their children suffer from similar effects as Tim and Tiffany.

Facilitating the Simulation:

BACKGROUND

-

The simulation will be performed in groups of five to six people, one will be the representative of the five or six profiles involved.

-

Participants are provided with the briefing sheet displayed on the smart board and a profile sheet.

-

Participants must read and think of persuasive arguments to fulfill their objectives.

-

An innovative strategy must be negotiated.

BRIEFING

Begin the exercise by dividing participants into groups of five to six. Allow group members 20 minutes to read over their briefing/profile sheets and become familiar with the situation described. Clarify any questions before beginning the exercise. Have each group begin by having participants introduce themselves in their role and personal situation. Remind participants about their background and goals.

DURING THE SIMULATION

Each group should spend about 30/40 minutes discussing the rights of each represented sector. Participants will use their own personal strategies to persuade the others by negotiating possible, innovative alternatives. A consensus solution should be achieved.

Note

All members must agree to a decision (i.e. a consensus). If multiple groups perform simultaneously and the situation is recorded in order to assess the participants ‘performance later, it is advisable to hold the sessions in separate rooms in order to get clear sound and avoid the different groups’ influencing one another.

DEBRIEFING

When all of the groups have arrived at their final decision allow them to discuss:

-

The situation itself

-

Their performance

-

The innovative option agreed upon

-

Their feelings and proposals for improvement

-

Their perception of learning

-

Their perceptions of simulation in EFL classes

Debriefing can be conducted intra-groups first. A wrap-up discussion may take place afterward.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Angelini, M.L. (2023). A Case Study of Simulation Design in a Postgraduate Teacher Training Course. In: Angelini, M.L., Muñiz, R. (eds) Simulation for Participatory Education. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21011-2_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21011-2_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-21010-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-21011-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)