Abstract

The present chapter provides an overview of the stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure as it has been studied within applied behavior analysis, particularly in efforts to develop early vocalizations among individuals who are nonvocal or minimally vocal. The chapter begins with an overview of the conceptual foundations of the stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure, with specific attention to the respondent, conditioned reinforcement, and automatic reinforcement processes involved. Early research on the procedure is then reviewed, followed by an overview of literature reviews and more recent research. The chapter concludes with some implications for future research and practice, as well as a brief consideration of stimulus pairing research beyond that which is the focus of the chapter.

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Chapter Overview

This chapter focuses on the use of stimulus-stimulus pairing (SSP) procedures in the development of behavior. In particular, this chapter focuses upon the use of these procedures in the development of early language, with a focus upon using SSP to promote language with individuals with language delays (e.g., those associated with autism spectrum disorder; ASD), and in particular, individuals with very minimal or no vocal language. The chapter begins with a conceptual overview of the principles involved in SSP intervention strategies. This includes a consideration of both the respondent and operant principles that are thought to be the foundation of SSP. In addition, as some of the literature on stimulus pairing is related to other areas of application and research (e.g., derived stimulus relations), the chapter concludes with a brief consideration of how stimulus pairing procedures are fundamental to many areas in applied behavior analysis.

One more thing before we begin. Although this chapter focuses upon stimulus pairing procedures in the development of behavior (especially language skills), we recognize that stimulus pairing procedures are also used to reduce challenging behavior. For example, the literature on environmental enrichment could be interpreted from the perspective of SSP in the sense that stimuli are paired with (or added to) the current environment (e.g., Gover et al., 2019). In addition, many fearful or “phobic” responses likely develop as a result of stimulus pairings, and behavioral intervention to reduce those responses involves stimulus pairing, specifically stimulus un-pairing (e.g., Shabani & Fisher, 2006). Although these lines of research are interesting and pertain to meaningful clinical issues, they are not the focus of the present chapter. We mention them to acknowledge that a multitude of interventions may be considered to involve stimulus pairing; the focus of this chapter is rather specific in this regard. We turn now to conceptual foundations pertinent to our review of stimulus pairing and the development of language.

Conceptual Foundations

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) has a long history of scholarly work in the area of verbal behavior. Like many areas of behavior analysis, this particular area of application has been heavily influenced by the work of B. F. Skinner. In particular, Skinner’s (1957) text Verbal Behavior has had a significant influence on research and practice in ABA for many years (e.g., Dixon et al., 2011; Sundberg, 2008; Sundberg & Michael, 2001). Consistent with much of Skinner’s work, this area of focus has largely focused on an operant analysis of verbal behavior in an effort to understand how contingencies participate in language development. Other chapters in this text (Chaps. 22 and 68) have focused on providing an overview of this work, including the verbal operants and the various areas where Skinner’s analysis has been demonstrated to be particularly helpful (also consult Garcia et al., 2020; Rosales et al., 2020 for recent reviews of the research in this area).

Approaches to language development within ABA have not been limited to applications based on operant conditioning, however. Like other areas of practice (e.g., the treatment of phobias), the area of language development has also been influenced by the respondent conditioning paradigm. Respondent processes may be particularly relevant in circumstances when there is no behavior to reinforce, such as when an individual has not yet begun to engage in vocal behavior or only engages in very minimal vocal behavior. Whereas operant conditioning places heavy emphasis on the assessment and manipulation of the consequences of behavior to develop and influence particular behavioral targets (in this case verbal behavior), respondent procedures place emphasis on the pairing (i.e., co-occurrence) of stimulus events together in space and time to develop and influence the development of behavior. We turn now to reviewing the conceptual foundations of SSP more specifically.

Stimulus-Stimulus Pairing

This section provides an overview of the respondent and operant processes involved in SSP. While it is unlikely that the processes occur in a precise order, we attempt to review them sequentially to lay out the mechanisms involved in the procedure.

The stimulus-stimulus pairing (SSP) procedure is derived from conceptual work in the area of behavioral development (e.g., Bijou, 1993) and Skinner’s (1957) verbal behavior. Interestingly, this area of conceptual analysis may have developed, at least partially, in response to the traditional idea that some language seems to develop in the absence of a specific history of reinforcement. Indeed, at first thought, the idea that language might develop in the absence of a particular history of reinforcement would seem to threaten the most fundamental assumptions in behavioral thinking. Not surprisingly, this issue has been used as a critique of the behavioral position as an explanation of language development for years (consult Sundberg et al., 1996 for an overview). Behaviorists have attempted to explain this development of behavior in the absence of a history of reinforcement by emphasizing the distinct processes involved – and they are fundamental to understanding SSP.

From the behavioral perspective of language development, a great deal of language may be influenced by a sequence of three processes and related outcomes (e.g., Sundberg et al., 1996). First, and perhaps most fundamentally, there is the pairing of sounds with preferred or non-preferred stimulus events. For example, parents/caregivers often make sounds and say words while holding an infant, providing access to food, playing with the infant, and more (i.e., the sounds are paired with stimulus events). Following the respondent conditioning paradigm, the sounds, words, and more may be considered neutral stimuli that are paired with unconditioned reinforcers (e.g., food) or stimuli that are already conditioned reinforcers (e.g., the sight of a toy). As a result of these stimulus-stimulus pairings, those sounds, words, and more, while previously neutral stimuli, become conditioned stimuli themselves. This sort of pairing is pervasive throughout the lives of young children, and a great deal of early learning likely involves respondent conditioning. Readers of this chapter are encouraged to pause for a moment and consider the extensive number of sound-event pairing trials that likely occur in the day-to-day lives of young children from the time they wake until they go to sleep. At the same time, considering this may also lead to the understanding of the impact of childhood neglect on language development (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995).

This first step explains how sounds and words first develop the stimulus properties of unconditioned and already conditioned stimuli – how those sounds become conditioned stimuli themselves. The second step points to the development of operant functions for the sounds targeted in step one. Specifically, it is hypothesized that this history of respondent conditioning (i.e., the stimulus-stimulus pairing) leads to those previously neutral stimuli (i.e., the sounds) now functioning as conditioned reinforcers in the operant sense of the phrase (and indeed, all conditioned reinforcers are established via respondent processes). In this sense, the respondent conditioning (Step 1) sets the stage for subsequent operant conditioning. Furthermore, when something functions as a conditioned reinforcer, the presentation of the conditioned reinforcer increases the future frequency of behavior that resulted in its presentation. In this case the conditioned reinforcer is the sound (i.e., the previously neutral stimulus), and the presentation of the sound (i.e., the hearing of the sound) may reinforce the behavior that produces it (i.e., the vocal behavior on behalf of the person who is developing language). It is this operant conditioning that serves to explain how the initial vocalizations of the individual (e.g., babbling) may begin to increase in frequency.

The third step in the process is automatic reinforcement. It probably is not a “step” in the sense that it does not happen after step two (more on this in a moment), but it is more of a concept that may be useful in explaining a critical part of SSP. Recall that one of the main issues that may be used to critique the behavioral position is that language seems to develop in the absence of a specific history of reinforcement, for example, that an adult did not mediate reinforcement contingent upon every single vocalization that a child engages in. In fact, it seems likely that it is often the case that a child begins to engage in some vocal behavior without there being a particular history of reinforcement to point to as the explanation. Given the respondent conditioning involved in step one, and the establishment of sounds as conditioned reinforcers in step two, engaging in any behavior that produces a target sound may be reinforced. However, this particular behavior is unique in that the reinforcement is “built in”; it occurs automatically. Nobody needs to do anything to mediate the reinforcement for engaging in the vocal behavior, and the delivery of reinforcement is not contingent upon any particular environmental condition. In other words, both the behavior (i.e., engaging in the vocalization) and the reinforcer (i.e., hearing the sound of the vocalization) can occur at anytime and anywhere.

Moreover, the shaping process may also occur automatically, whereby the vocalizations and related sound products become more and more similar to the sounds involved in the initial respondent conditioning, still without any requirement that someone mediates reinforcement. All of these make the SSP particularly unique, conceptually speaking, since environmental support is not needed beyond the initial respondent pairing in step one. Although automatic reinforcement may often cause problems when challenging behavior is involved, it is quite helpful when it is built into the process of behavioral development. The automatic reinforcement concept seems to be rather important, not only to finish explaining this part of the behavior analysis of language development, but also to respond to common critiques of behavior analytic approaches to language (readers interested in this may also consult Palmer [1996]).

We have described the respondent and operant processes involved in SSP in a somewhat sequential manner. However, it is important to note that the respondent and operant processes described thus far are more likely to be ongoing (i.e., to co-occur) or to sort of go back and forth. For example, imagine an infant who has a caregiver that says “ba-ba-ba” while playing with the infant. Respondent conditioning may occur, and the infant’s vocalizations may begin to be exposed to operant contingencies. However, it is likely that additional SSP will occur, for example the parent saying “yes, ba-ba-ba!” while tickling the infant after the infant engages in an approximation, meaning that additional respondent conditioning may occur. This respondent conditioning may influence operant processes, and vice versa. Our point here is that while we have described the processes involved in SSP as a series of sequential steps, it seems more likely that they co-occur and together contribute to the development of vocal behavior.

Why Stimulus-Stimulus Pairing?

So far we have described the processes that explain the development of vocal behavior, the processes that are the foundation for SSP as an intervention. That is, the above is a description of how early vocalizations develop, whereas SSP involves the specific application of techniques based upon those processes. The former is a conceptual explanation, whereas the latter is a technique derived from that conceptualization.

Importantly, the SSP is not just any technique, and developing early vocalizations is just one component in a larger effort to develop language. Indeed, these early vocalizations provide the context by which additional conditioning might be applied. The sound “mmm” is not an end goal in itself; it allows for further conditioning that may lead to the word “mom” and “milk”, for example. Moreover, applied behavior analysts frequently work with individuals with language delays, including individuals with autism spectrum disorder and related intellectual disabilities, some of whom are minimally vocal or nonvocal altogether (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Therefore, it may be the case that applications of SSP are crucial to the development of early language. Given the significance of developing language in many areas of day-to-day living, it would seem that applied behavior analysts working on language development should have knowledge of interventions that may be helpful.

On this note, we turn to the research literature on the SSP. We review some of the early studies on SSP, two recent literature reviews, and literature that has been published after these literature reviews (post-2014).

Stimulus-Stimulus Pairing Research

Early Research

To our knowledge, SSP was first empirically examined by Sundberg et al. (1996). In this study, researchers examined the effects of SSP on novel vocal behavior, specifically the babbling repertoires of four children with severe to moderate language delays and one child without any language delays. In the first of two experiments, the four participants were exposed to the SSP procedure, which involved a novel sound, word, or phrase that was paired with a previously established conditioned or unconditioned reinforcer during play periods. During the post-pairing condition, all participants were observed to emit unprompted vocal and verbal behavior, with occasional emissions during participants’ vocal play outside of pairing sessions. Moreover, an increase in the overall vocal responses of some participants was seen following SSP. Sundberg et al. suggested that the effect on overall vocal responses might have been a result of SSP functioning as direct reinforcement for vocalizations emitted during baseline conditions (i.e., adventitious reinforcement may have occurred). Yet, there were some instances in which an increase in vocal behavior was not observed following SSP. In order to examine a variety of parameters of the SSP procedure, a second experiment was conducted with the participant whose overall vocal responses did not increase in the first experiment.

A number of variations to the SSP procedure were included in the second experiment. The first procedural variation examined the lack of an increase in vocal behavior during play following SSP. Sundberg et al. (1996) suggested that failures to increase vocal behavior were a result of procedures being delivered by adults unfamiliar to the participant, as well as the participant’s current emotional state during procedures. Specifically, Sundberg et al. observed that when the participant was “quiet and sullen,” an increase in vocal behavior during periods of play was not observed following SSP. Therefore, the novel topography of a previous vocalization was paired more frequently and with longer durations of reinforcement. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of SSP.

The second procedural variation examined the maintenance of pairing by including an extended baseline and post-pairing condition. Here, procedures were identical to experiment one, with the exception that the session did not conclude until the participant no longer engaged in new topographies of vocal behavior. Results indicated that the post-training condition ceased after five minutes; compared to the pretraining conditioning lasting approximately nine minutes, these results suggested that the effects of SSP were temporary. Sundberg et al. (1996) hypothesized that such effects could be a result of the number of pairings, the extent to which the preferred stimulus functioned as a reinforcer, and the participant’s current establishing operations.

Finally, Sundberg et al. (1996)’s third procedural variation introduced a similar sounding, but incomplete phrase in order to disrupt a previously paired vocalization, since it was observed that such vocalizations were emitted after each new pairing. Procedures mirrored those of experiment one, with the exception of the use of a novel yet incompatible vocalization. Results from the post-pairing condition demonstrated that this procedural variation failed to alter the previously paired vocalization, which Sundberg et al. suggest is due to the saliency of history of reinforcement when the previous vocalization compared to contingencies associated with the novel vocalization. In light of the findings obtained from both experiments, Sundberg et al. were the first, to our knowledge, to examine and demonstrate the effectiveness of SSP on increasing vocalizations of children with minimal language.

In a follow-up study, Smith et al. (1996) studied the impact of three pairing procedures on the vocal behavior of two infants without language delays. The first procedure included the neutral condition, where any vocalizations that participants emitted during play were recorded (i.e., pre-pairing and post-pairing) and a sole phoneme was emitted by researchers without being followed by reinforcement (i.e., neutral presentation). The second procedure included the positive condition which was similar to the neutral condition, with the exception of the phoneme that was emitted by researchers being paired with an established reinforcer. To not directly reinforce emitted vocalizations or other behaviors (e.g., eye contact) of participants during pairing in the positive condition, a 15 s time-out period was included, where reinforcement was not delivered following such vocalizations or behaviors (i.e., this procedure was to control for potential operant conditioning, since the study focused on learning about the effects of SSP and not direct reinforcement). The final condition was the negative condition, which was also similar to previous conditions. Here, the researcher-emitted phoneme was paired with an established punisher (e.g., verbal reprimand). The findings of Smith et al. extended those of Sundberg et al. (1996), which demonstrated that the infants’ vocalizations increased following the positive pairing condition. Moreover, results from Smith et al. demonstrated minimal effects on vocalizations following the neutral condition and immediate and decreasing effects following the negative pairing condition, which suggested an automatic punishment effect. This study highlighted the importance of pairing a vocalization with a reinforcer during SSP.

These early studies set the stage for subsequent research on SSP, and indeed, there is a growing body of research in the area. In fact, review papers on SSP have been published in recent years, and in the subsequent section we provide attention to these overviews of the SSP literature. As the SSP procedure may be implemented in a variety of ways, the first review (Shillingsburg et al., 2015) analyzes the extent to which studies on SSP have varied across several dimensions. After reviewing this analysis of the SSP literature, we will provide an overview of a second review done by Petursdottir and Lepper (2015). This second review paper builds upon the work of Shillingsburg et al. in the sense that additional procedural variations on the SSP procedure are suggested. There are many opportunities for further research on SSP, and we call attention to these opportunities throughout.

Reviews of the Stimulus-Stimulus Pairing Literature

Shillingsburg and colleagues (2015) conducted a review of the research on SSP as a means to induce vocalizations. The researchers specifically looked at all of the literature published between the years 1996 and 2014 in an effort to assess how effective the SSP is, its variations, implications for practice, and opportunities for additional research. The review is noteworthy, as the researchers found a number of variations within the literature on SSP that may account for the varied outcomes found when the procedure has been researched.

The review by Shillingsburg et al. (2015) included 13 studies and a total of 39 participants. While many variables were coded in their review, we focus on those that seem especially relevant to further research and practice in this chapter. For example, one area that Shillingsburg et al. considered in their review of the literature was the participants’ language skills at the time of the study. It would make sense that the participants’ prerequisite skills may impact the extent to which the procedure is effective in promoting language. The researchers noted that a variety of measurements have been used in the literature (e.g., the Early Echoic Skills Assessment; Esch, 2008; the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), whereas some studies described the participants’ verbal skills but it was not clear whether or not an assessment was used. The researchers also distinguished between participants with functional language skills (i.e., those who vocally mand, tact, and/or engage in intraverbals) and those who did not have functional language skills (i.e., participants who make some sounds and/or engage in echoics). The authors found that 28/39 (72%) of the participants in the SSP studies reviewed did not have any functional language skills, whereas 11/39 (28%) did have some functional language. Thus, there have been differences regarding the incoming prerequisite skills of participants within the SSP literature.

Shillingsburg et al. (2015) also found that there was some variation regarding the sounds targeted during intervention across the SSP literature. Specifically, Shillingsburg et al. were interested in the extent to which entirely novel sounds were targeted relative to sounds that were already in the participants’ repertoire to some extent. Researchers found that 17/39 participants (44%) were exposed to SSP with novel target sounds, and 22/39 (56%) of participants were exposed to SSP with sounds that were already in their repertoires to some extent. In addition to these broad differences, the researchers noted that specific studies identified sounds to be targeted during SSP in idiosyncratic ways. That is to say that there is a lack of consistency with how sounds are identified within the “novel” and “within repertoire” groupings. This topic appears to be ripe with implications for additional research, as targeting a sound which has never occurred, occurs very rarely, or occurs with some reliability seems like it could differentially impact the effectiveness of the SSP procedure.

As we have described earlier in the chapter, SSP involves the pairing of a sound with another stimulus (i.e., a stimulus that already functions as an unconditioned stimulus, conditioned stimulus, and/or operant reinforcer). What is not specified in this general framework is the number of times the researcher/therapist makes the sound during each pairing trial. As with the areas described above, this topic too seems to be one where there is some inconsistency across the literature reviewed. In some studies, the target sound was made once per pairing; in others it was made three times, five times, and even seven times. Thus, there is great variety in how the specific pairings occur across the SSP literature reviewed by Shillingsburg et al. (2015). Interestingly, Shillingsburg et al. did not find that more pairings corresponded to better outcomes. Still, as the data on this are preliminary, more data are needed.

Another variable analyzed by Shillingsburg et al. (2015) is the number of pairings per minute. While a previous variable pertained to the number of times a sound was made per pairing trial, the present variable pertains to the number of sound-stimulus pairings per minute. In some ways, this could be considered a measure of the intensity of the intervention. The authors noted that this information is not always specifically stated within the research literature, but that it may be derived from descriptions of experimental procedures. Here too, Shillingsburg et al. noted great variation across studies, with the number of pairings per minute ranging from 1 to 15. This means that, in the same amount of time, participants in the SSP studies reviewed were exposed to 1–15 pairing trials per minute. This too is another area where the procedure is implemented quite differently across studies.

As a procedure involving respondent processes, Shillingsburg et al. (2015) also evaluated the type of pairing procedure that was used across SSP studies. The authors specifically evaluated the studies for the use of simultaneous, delay, trace, and discrimination training procedures. Simultaneous was defined as the sound and item/reinforcer being presented at the same time, delay was defined as the sound being presented (alone initially) with the preferred item being presented while the sound was still active, trace conditioning involved the presentation of the sound, with the sound stopping, and then the preferred item being presented, and finally, discrimination training involved the sound serving as a discriminative stimulus, such that a response was reinforced with the item, but only when the sound was present. As with other variables assessed in this review, Shillingsburg et al. found that this is yet another area indicative of inconsistency across the literature on SSP (conditioning procedures are given additional consideration in our review of Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) in the subsequent section).

Shillingsburg et al. (2015) also assessed the extent to which studies in the SSP literature controlled for adventitious (i.e., accidental) operant reinforcement. As we noted in the introduction to the chapter, the SSP procedure is based upon respondent conditioning, with stimulus-stimulus pairing being the fundamental feature of the intervention (in this case it is a sound-stimulus pairing). However, the participants in the studies may engage in the target sound at any time. Given this, it would be possible for the participants to engage in the target sound just before the preferred item is presented, resulting in the potential for operant conditioning (i.e., the participant engages in the target sound and this is followed by the presentation of an unconditioned or already conditioned reinforcer). If this happened, the target vocalization may increase in frequency, but this outcome may occur by way of operant conditioning, direct reinforcement contingencies, and not necessarily because of the SSP procedure. Given that the research studies reviewed aimed to study the SSP procedure, and not operant reinforcement contingencies, it is interesting to consider how many of the studies controlled for such adventitious reinforcement. Shillingsburg et al. found that 48% of the participants in the studies reviewed participated in studies that controlled for adventitious reinforcement, and 52% of the participants in the studies did not. Moreover, the procedures used by studies that did attempt to control for adventitious reinforcement were not consistent. This too seems to be an area with opportunities for further research, with specific implications for understanding the mechanisms responsible for the behavior change found in SSP studies. These issues may seem less important from a clinical perspective at first, but they may help to focus the attention of clinical work such that practitioners place emphasis on behavioral processes that are more critical to effective outcomes.

Yet another variable related to the use of SSP as an intervention pertains to the specific stimulus paired with the sound (remember the early study by Smith et al. related to this topic). Given that the pairing (in space and time) between the sound and the stimulus is the foundation of the SSP, it would make sense that the stimulus being paired with the sound be given a great deal of consideration. Generally, we might assume that pairing a sound with an item that is highly preferred, and demonstrated to function as a very reliable reinforcer, might result in better outcomes than pairing the sound with an item that is only somewhat or moderately preferred, and a less reliable reinforcer. Shillingsburg et al. (2015) noted that there was some effort to identify and use highly preferred and reinforcing stimuli within the SSP studies reviewed, but that the exact way in which these stimuli were identified varied across studies. Moreover, Shillingsburg et al. found that a range of types of stimuli were used in SSP studies, including social, tangible, and edible stimuli. While it is noteworthy that some consistency is observed in the sense that there seems to be a general effort to identify and use preferred and reinforcing items within this literature, there is room to improve standardization across studies to better understand the extent to which specific stimuli facilitate (or not) the effectiveness of the SSP intervention.

The previous paragraphs focused on reviewing some of the variables targeted in the Shillingsburg et al. (2015) review of the SSP literature. Importantly, the authors concluded their review by considering the overall effectiveness of the SSP intervention, as well as the extent to which different variables were associated with intervention effectiveness. We consider some of these conclusions in the next section.

Overall Effectiveness of the SSP/Results Obtained

As we have mentioned in the paragraphs above, studies evaluating SSP have been conducted in a variety of ways. This broad finding makes it difficult to draw any firm conclusions regarding the research literature. Still, Shillingsburg et al. (2015) note that there are some themes that may be emerging and point to opportunities for additional research on the procedure. Perhaps most interesting is the overall analysis of the effects of the SSP intervention. When looking at specific evaluations for specific sounds, Shillingsburg et al. found that 34% of the evaluations had a weak effect, 49% had a moderate effect, and 17% had a strong effect. Thus, the effects of the intervention appear to be mixed when they are considered on the whole, while at the same time the majority (66%) of the evaluations of SSP were associated with some effect (moderate or strong). The authors also found that children 5 and younger were more likely to have moderate or strong effects when compared to older children, though at the same time recognized that evaluations with older children were fewer in number. In addition, while assessments of prerequisite language/skills varied across the studies, the authors found that participants with no functional language (i.e., those who only engaged in some vocal behavior and/or echoics) were more likely to have a stronger effect with SSP. This area seems to be of interest to both researchers and practitioners – and again, while firm conclusions are difficult to make, it seems possible that there are implications for future research and practice here.

Also, as the number of specific evaluations the authors reviewed for effect size was limited, the authors were not able to determine potential differences between interventions that involved novel relative to in-repertoire stimuli within SSP. Other factors seemed to be associated with more effective applications of SSP, including the use of procedures to control for adventitious reinforcement, the use of edibles, and delayed pairing procedures. The authors found that the number of researcher/therapist pairings per trial did not necessarily result in better outcomes; and related to this, when there were 5 or more pairings per minute the results were actually more likely to be weak. It seems possible that habituation processes may contribute to this finding. At the same time, there are many variables at play in the research on SSP, and it is difficult to draw any conclusions, let alone any firm conclusions. Much more research is needed to better understand these issues.

As mentioned earlier, a second review paper was published around the same time as the Shillingsburg et al. (2015) paper, and among other things, it focused on additional procedural variations that may warrant consideration within the SSP research.

Procedural Variations

A second review of the stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure was published in 2015, though with a bit of a different focus. Similar to Shillingsburg et al. (2015), Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) provided a general overview of the literature on SSP, noting the range of ways in which SSP has been studied within the research literature as well as the inconsistent outcomes it is associated with. Interestingly, Petursdottir and Lepper noted that there may be many reasons for the inconsistent findings of the research literature, and that one of the factors to consider might be the more general approach to conditioning sounds as reinforcers within the SSP literature; in particular, the fact that the SSP involves presenting stimuli in the absence of any particular response requirement. The authors describe some research which has focused on alternative procedures to condition reinforcers, research with implications for understanding how the SSP might be further studied and refined. We review some of these studies below. For the purposes of this chapter, these conditioning procedures might be categorized as discrimination training and response independent/dependent pairings.

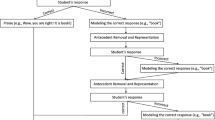

Discrimination Training

One conditioning procedure that involves a response requirement for participants is discrimination training. Whereas the SSP model generally involves presenting sounds and preferred stimuli together in the absence of a response, discrimination training involves the sound being a discriminative stimulus, where engaging in a target response in the presence of the sound results in reinforcement, and engaging in the target response in the absence of the sound does not. In this model the sound becomes a discriminative stimulus, and perhaps as a result of this conditioning, the sound may become a conditioned reinforcer itself. A couple of studies have compared discrimination training with stimulus-stimulus pairing procedures (Isakesen & Holth, 2009; Lepper et al., 2013). Lepper et al. compared the effects of a discrimination training and stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure to establish vocalizations with nonvocal children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Results showed that both conditioning procedures were effective at increasing vocalizations among the participants, with no difference as far as one being more effective than another. Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) note that this might make the traditional SSP more desirable as it is easier to implement. It is noteworthy that participants in the Lepper et al. study preferred the discrimination training procedure, however. Regardless of all of this, given that we know the traditional SSP procedure has mixed results, Petursdottir and Lepper suggest that the discrimination training procedure may represent an option to explore when SSP is not effective. Though again, much more research is needed to explore this possibility.

Response-Independent/-Dependent Pairings

A study by Dozier et al. (2012) examined two different pairing procedures to condition praise statements as reinforcers. In one of the conditions (Experiment 1), praise statements, which were determined to be neutral and not function as reinforcers prior to the pairing intervention, were paired with highly preferred edible items. This condition was similar to the stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure in that two stimuli, praise statements and preferred edible items, were paired together in space and time. Results showed that this pairing condition was not effective for 3 of the 4 participants, with one participant showing some effect initially though this did not maintain over time. In the second condition, evaluated in Experiment 2, the pairing condition involved a response-stimulus pairing, where participants engaged in a target response and this was followed by the presentation of the praise statement and preferred edible item. Subsequent to this response-stimulus pairing condition, there was a test for the reinforcing effects of praise alone – to evaluate the extent to which the response-stimulus pairing condition established praise as a reinforcer. The response-stimulus pairing condition was effective for four of the eight participants in Experiment 2. Moreover, praise was also found to function as a reinforcer for additional responses with these four participants. While Dozier et al. were focused on conditioning praise statements as reinforcers, the response-stimulus pairing procedure studied may have implications for understanding how to improve the effects of SSP to increase vocalizations. Indeed, this was specifically explored in a recent study by Lepper and Petursdottir (2017), which is described in detail in the following section.

In general, the Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) review reminds us that while we may need to focus on understanding some of the details associated with successful applications of SSP, we also need to consider the more general pairing procedure and the extent to which alternatives, particularly those which require a response on behalf of the individual, could increase the effects of intervention efforts.

Recent Research

Following the literature reviews of Shillingsburg et al. (2015) and Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) on the SSP, empirical research on the effects of SSP to increase novel vocalizations and condition vocalizations as reinforcers has continued. In 2017, Lepper and Petursdottir conducted two experiments which evaluated the effects of a response-contingent pairing (RCP) procedure on vocalizations of target syllables for three children with ASD who engaged in minimal functional vocal verbal behavior. As the name suggests, RCP is used to establish vocalizations as reinforcers by pairing a neutral stimulus with a reinforcer and delivering the reinforcer contingent on a response. This procedure was compared to the response-independent pairing (RIP) procedure, similar to the SSP that we have been describing thus far in the chapter, where two stimuli (e.g., a sound and a reinforcer) are presented in the absence of a particular response from the individual.

In the first experiment, Lepper and Petursdottir (2017) compared RCP and RIP. During RCP sessions, 20 sound presentations were included and consisted of 10 target and 10 nontarget sounds presentations. Before undergoing experimental procedures, participants were taught to engage in a button-pressing response, which allowed for delivery of preferred items. RCP sessions began with the button being placed in front of the participants so that an opportunity to press it was presented. After participants pressed the button (in the presence or absence of a prompt), a target or nontarget sound was presented three times with 1 s between presentations, along with the simultaneous delivery of a preferred item and the removal of the button. Once the preferred stimuli were consumed, an intertrial interval began. The button was presented again 10 s into the intertrial interval, with the intertrial interval ending when the participant pressed the button again. If participants engaged in a target or nontarget vocalization just before a preferred item was to be delivered, the item and button were removed and represented after 20 s of no vocalizations; this was done to prevent direct reinforcement of such vocalizations (recall our description of procedures that control for adventitious reinforcement earlier in the chapter).

Sessions of RIP mirrored those of RCP, with the exception of the button not being presented, eye contact being obtained prior to the presentation of nontarget sounds or presentation of target sounds and delivery of a preferred item, the set of target and nontarget sounds differing, and each intertrial interval being yoked to a previous RCP session to equate durations of sessions and to increase deprivation or satiation of preferred items across the two interventions. Results from the first experiment demonstrated that more target vocalizations per minute occurred following RCP, despite absolute rates of such vocalizations being low and ranging from 0 to 1.69 per minute. To increase the rates of these target vocalizations to clinically acceptable levels, Lepper and Petursdottir (2017) utilized differential reinforcement with social reinforcement in a second experiment while including pairings for maintenance.

Procedures of the second experiment consisted of RCP, with the exception of the immediate delivery of preferred items following target vocalizations and the simultaneous removal of the response button if it was present, the response button being presented again only after a 10 s absence of a target vocalization, and prolonged contact with preferred stimuli when target vocalizations occurred while participants were already consuming a preferred stimulus. Data indicated that differential reinforcement increased target vocalizations compared to RCP alone for all participants. While target vocalizations occurred at low rates during extinction in the first experiment and during baseline of the second experiment, the rates of such target sounds increased to clinically relevant levels following differential reinforcement. Results from Lepper and Petursdottir (2017) demonstrated that the efficacy of pairing procedures such as SSP may be enhanced when stimuli are presented contingent on responses and that the effects of pairing procedures such as RCP may be enhanced when differential reinforcement is used in conjunction with maintenance pairings.

Another recent study was conducted by Cividini-Motta et al. (2017), who were specifically interested in better understanding procedures to improve echoic training given the mixed results within this literature. Cividini-Motta et al. devised an assessment protocol to identify the most effective echoic teaching procedure among vocal imitation training, SSP, and the mand-model procedure. The researchers also conducted functional analyses to determine whether trained responses functioned as echoics or mands. Six children diagnosed with autism and related disorders, ranging in age from 7 to 17 years old, completed a series of echoic probes and functional analysis probes, as well as a semi-random order of vocal imitation training, mand-model teaching, SSP, and play sessions. Specifically during the SSP condition, the target sound was presented five times, with 1 s intertrial intervals. Prior to beginning sessions, participants were allowed to select a preferred item, which was presented between the second and fifth presentation of the target sound during SSP sessions. The assessment protocol identified an effective echoic training procedure for five of six participants. Although SSP was the most effective procedure for some participants, authors suggested that carry-over effects might have impacted results. Specifically, participants’ echoics were directly reinforced during vocal imitation training and mand-model teaching, which could have increased the likelihood of engaging in vocal imitation during SSP as a result of the novel history of reinforcement for this response. As a result, Cividini-Motta et al. (2017) proposed evaluating the effects of SSP first prior to vocal imitation training and mand-model procedures, in addition to providing direct reinforcement of vocal imitation when utilizing SSP to increase echoic responding.

While early research on SSP involved adults who had a history of implementing procedures with participants (Smith et al., 1996; Sundberg et al., 1996), the majority of SSP evaluations within the research literature have been delivered by researchers (i.e., unfamiliar adults), which may impact outcomes as well as the maintenance and generalization of clinical gains. Moreover, the conceptual model described earlier in the chapter is generally assumed to involve someone who has been paired with a variety of reinforcers (i.e., someone who is likely to be established as a generalized conditioned reinforcer for various behavior the child engages in). Therefore, Barry et al. (2019) assessed the impact of a parent-implemented SSP intervention with two children with ASD who did not engage in vocal verbal behavior. Experimental procedures consisted of five phases: baseline, SSP, direct reinforcement, noncontingent reinforcement, and a return to direct reinforcement. During SSP, one pairing sound per trial was utilized. Prior to intervention phases, behavioral skills training was used to train parents on the delivery of SSP.

Across both participants, higher frequencies of target responses were seen across all experimental procedures relative to baseline, while nontarget responses remained the same. SSP initially increased target responses, such increases continued when differential reinforcement was utilized, and SSP was effective in conditioning vocalizations as reinforcers. Barry et al. (2019) also assessed social validity via a questionnaire inquiring about parents’ experiences with the intervention. With mean scores being 4.3 out of five, responses from both parents suggested high social validity in areas such as SSP allowing for meaningful one-on-one time with their children, confidence in the ability to conduct SSP, and increased vocalizations following the intervention. The research of Barry et al. not only extended the literature of SSP, but more importantly provided preliminary support for training parents to deliver procedures to increase their children’s early vocalizations, which can allow for increased learning opportunities and generalize and sustain vocalizations.

The most recent study evaluating SSP is that of Freitas et al. (2020). As there has been little attention to how different respondent conditioning procedures influence the outcomes of SSP, Freitas et al. aimed to further link SSP with respondent conditioning research by comparing the effects of forward versus backward pairing on echoics and quantitatively assessing the relation between participants’ current skill levels and the efficacy of SSP. Twelve children with ASD, seven residing in the United States and five residing in Brazil, with limited vocal verbal behavior and delays in language served as participants. During baseline, participants’ vocalizations were recorded during free play; of those one syllable recorded vocalizations, three were selected to serve as target sounds and were randomly assigned as forward sounds or backward sounds. During the forward conditioning sessions, the forward sound was presented first by researchers, followed by the immediate delivery of the preferred item; this differed from the backward conditioning sessions, where sounds emitted by researchers were also paired with a preferred item, but the order was reversed (i.e., the preferred item was delivered immediately before the backward sound). Control sounds were also included, which consisted of a sound uttered by researchers in the absence of preferred items.

Intervention consisted of target sounds being emitted for 2 s and participants engaged with preferred stimuli for 10 s. Results obtained from Freitas et al. (2020) demonstrated that SSP increased the mean response count per session when forward pairing was utilized. Moreover, there were differences in the effects of forward and backward sounds with SSP; specifically, fewer echoics were emitted with backward sounds in comparison to other sounds (i.e., forward and control). The results also pointed to an inverse relation between the Behavioral Language Assessment Form (BLAF; Sundberg & Partington, 1998) and the effectiveness of SSP. Overall, SSP was more effective for participants who had fewer skills at the beginning of the study. Moreover, results suggested that the forward pairing procedure was more effective than the backward pairing procedure for participants of the study.

Implications for Research and Practice

As we have noted throughout, there are many opportunities for further research to better understand the SSP procedure and its use to develop early vocalizations. We offer some general recommendations and highlight themes for further analysis below, as well as some implications for practice. As always, decisions that researchers and practitioners make should always be informed by research and ongoing progress monitoring. Given what we know about SSP, it should not be assumed that SSP will effectively increase early vocalizations. As we have noted throughout this chapter, findings are not consistent and it is difficult to know the exact conditions under which the procedure is most likely to be effective. Practitioners considering the SSP procedure should monitor progress carefully and consider alternative procedures (some of which have been described in this chapter) and discontinue the use of SSP if desired behavior change is not occurring. For example, procedures described by Petursdottir and Lepper (2015) may be promising when traditional SSP is not effective; and this too represents an area for further investigation. Next, current data suggest that SSP is most effective with children who are younger (i.e., 5 and under; Shillingsburg et al., 2015). Though this is quite tentative and additional research is needed to support or counter this hypothesis, it is something that practitioners should be aware of.

Behavior analysts should also always consider the learner’s prerequisite skills when conducting studies in this area; even when the SSP procedure does not increase target vocalizations or establish novel vocalizations, the circumstances surrounding less effective applications can still be identified. Paying closer attention to prerequisite skills will not only aid in the understanding of when SSP is more or less likely to be effective, but also help to understand the overall progression of early behavioral development more generally (e.g., to help identify critical cusps to target before SSP). In addition, relatively little is known about the differential effects of targeting novel sounds relative to sounds that are already in the individual’s repertoire (even just minimally). Moreover, it’s possible that sounds should be targeted in a particular sequence, or that if one or two particular sounds are occurring minimally, one might be a better candidate to target next, etc. These issues, both the topic of assessing prerequisite skills and identifying specific targets for intervention, present opportunities for applied behavior analysts to collaborate with speech-language pathologists who have specific expertise in these areas (Association for Behavior Analysis International, 2021).

Finally, researchers and practitioners should consider the implications of participant histories with different therapists implementing SSP, including familiar adults, unfamiliar adults, and parents/caregivers, and others. It seems possible that different therapist histories with participants will influence the effects of SSP, and this factor is deserving of more attention from researchers and clinicians. Moreover, if results using SSP continue to suggest that the procedure is most effective for children under 5 years old, training parents/caregivers to utilize SSP with high fidelity may facilitate more widespread and lasting influence on child vocalizations.

Conclusion

Before we conclude, we would like to again acknowledge that a great deal of interventions may fall under the purview of stimulus-stimulus pairing. For example, researchers interested in the development of stimulus equivalence have studied the extent to which two stimuli may be presented in a respondent manner in efforts to promote the development of equivalence relations (e.g., Leader & Barnes-Holmes, 2001). Related to this, stimulus pairing has also been involved in research on the Stimulus Pairing Observation Procedure, where picture-word relations have been presented to participants and found to be functionally related to the development of listener responses (e.g., point to the “word”; Byrne et al., 2014). Other studies have also focused on pairing procedures to condition other responses, such as conditioning observing responses (e.g., Greer & Ross, 2008). We mention these areas here to acknowledge that stimulus-stimulus pairing is related to many areas of research in behavior analysis, including derived stimulus relations and the development of many important behavioral cusps.

We have provided a general overview of the stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure as it has been used to produce novel vocalizations among individuals with language delays. If there are any broad conclusions to make, it is that we have much more to learn regarding how and when the SSP procedure is likely to be more or less effective. Given the importance of developing early vocalizations as a foundation for subsequent language development, detailed analyses of variables we have discussed in this chapter seem warranted.

References

Association for Behavior Analysis International. (2021). Interprofessional collaborative practice between behavior analysts and speech-language pathologists. https://www.abainternational.org/media/180194/abai_interprofessional_collaboration_resource_document.pdf

Barry, L., Holloway, J., & Gunning, C. (2019). An investigation of a parent delivered stimulus-stimulus pairing intervention on vocalization of two children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 35(4), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-018-0094-1

Bijou, S. (1993). Behavior analysis of child development. Context Press.

Byrne, B., Rehfeldt, R. A., & Aguirre, A. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of the stimulus pairing observation procedure and multiple exemplar instruction on tact and listener responses in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 30(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-014-0020-0

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Signs and symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/signs.html

Cividini-Motta, C., Scharrer, N., & Ahearn, W. H. (2017). An assessment of three procedures to teach echoic responding. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 33(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-016-0069-z

Dixon, M., Baker, J. C., & Sadowski, K. A. (2011). Applying Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior to persons with dementia. Behavior Therapy, 42(1), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.05.002

Dozier, C. L., Iwata, B. A., Thomason-Sassi, J., Worsdell, A. S., & Wilson, D. M. (2012). A comparison of two pairing procedures to establish praise as a reinforcer. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(4), 721–735. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2012.45-721

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test-III. American Guidance Service.

Esch, B. E. (2008). Early echoic skills assessment (EESA). In M. L. Sundberg (Ed.), Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: The VB-MAPP. AVB Press.

Freitas, L., Henry, J. E., Kelley, M. E., & tonneau, F. (2020). The effects of stimulus pairings on autistic children’s vocalizations: Comparing forward and backward pairings. Behavioural Processes, 179, 104213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2020.104213

Garcia, Y., Rosales, R., Garcia-Zambrano, S., & Rehfeldt, R. A. (2020). Complex verbal operants. In M. Fryling, R. A. Rehfeldt, J. Tarbox, & L. J. Hayes (Eds.), Applied behavior analysis of language and cognition: Concepts and principles for practitioners (pp. 38–54). New Harbinger.

Gover, H. C., Fahmie, T. A., & Mckeown, C. A. (2019). A review of environmental enrichment as treatment for problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.508

Greer, R. D., & Ross, D. E. (2008). Verbal behavior analysis: Inducing and expanding new verbal capabilities in children with language delays. Pearson.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young american children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Isaksen, J., & Holth, P. (2009). An operant approach to teaching joint attention skills to children with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 24(4), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.292

Leader, G., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2001). Establishing fraction-decimal equivalence using a respondent-type training procedure. The Psychological Record, 51(1), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395391

Lepper, T. L., & Petursdottir, A. I. (2017). Effects of response-contingent stimulus pairing on vocalizations of nonverbal children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(4), 756–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.415

Lepper, T. L., Petursdottir, A. I., & Esch, B. E. (2013). Effects of an operant discrimination training procedure on the vocalizations of nonverbal children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 656–661. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.55

Palmer, D. C. (1996). Achieving parity: The role of automatic reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 65(1), 289–290. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1996.65-289

Petursdottir, A. I., & Lepper, T. L. (2015). Inducing novel vocalizations by conditioning speech sounds as reinforcers. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(2), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-015-0088-6

Rosales, R., Garcia, Y. A., Garcia, S., & Rehfeldt, R. A. (2020). Basic verbal operants. In M. Fryling, R. A. Rehfeldt, J. Tarbox, & L. J. Hayes (Eds.), Applied behavior analysis of language and cognition: Concepts and principles for practitioners (pp. 20–37). New Harbinger.

Schillingsburg, M. A., Hollander, D. L., Yosick, R. N., Bowne, C., & Muskat, L. R. (2015). Stimulus-stimulus pairing to increase vocalizations in children with language delays: A review. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 31(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40616-015-0042-2

Shabani, D. B., & Fisher, W. W. (2006). Stimulus fading and differential reinforcement for the treatment of needle phobia in a youth with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(4), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.30-05

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Prentice-Hall.

Smith, R., Michael, J., & Sundberg, M. L. (1996). Automatic reinforcement and automatic punishment in infant vocal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 13(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392905

Sundberg, M. L. (2008). Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program. AVB Press.

Sundberg, M. L., & Michael, J. (2001). The benefits of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 698–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445501255003

Sundberg, M. L., & Partington, J. W. (1998). Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. AVB Press.

Sundberg, M. L., Michael, J., Partington, J. W., & Sundberg, C. A. (1996). The role of automatic reinforcement in early language acquisition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 13(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392904

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Baires, N.A., Fryling, M. (2023). Stimulus-Stimulus Pairing. In: Matson, J.L. (eds) Handbook of Applied Behavior Analysis. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19964-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19964-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-19963-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-19964-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)