Abstract

Digital technologies in the workplace have undergone a remarkable evolution in recent years. Biosensors and wearables that enable data collection and analysis, through artificial intelligence (AI) systems became widespread in the working environment, whether private or public. These systems are heavily criticised in the media and in academia, for being used in aggressive algorithmic management contexts. However, they can also be deployed for more legitimate purposes such as occupational safety and health (OSH). Public authorities may promote them as tools for achieving public policy goals of OSH, and public employers may use them for improving employees’ health. Despite these positive aspects, we argue that the deployment of AI systems for OSH raises important issues regarding dual use, chilling effects and employment discrimination. We exemplify how these ethical concerns are raised in three realistic scenarios and elaborate on the legal responses to these issues based on European law. Our analysis highlights blind spots in which laws do not provide clear answers to relevant ethical concerns. We conclude that other avenues should be investigated to help determine whether it is legally and socially acceptable to deploy AI systems and eventually promote such tools as means to achieve the OSH public policy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The use of new digital technologies in the workplace has undergone a remarkable evolution in recent years, especially since the outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis [1, 2]. Artificial intelligence (AI) systems, the internet of things (IoT), mobile devices, big data applications and advanced robotics are among the components of the new digital technologies enabling this evolution. The high degree of interconnectivity made possible by these digital technologies is conducive to what is called ‘algorithmic management’, when algorithmic software has the power to ‘assign, optimise, and evaluate human jobs through algorithms and tracked data’ [3, 4]. The increased use of digital technologies has adverse effects repeatedly denounced by media. Specifically, digital intrusion in the workplace becomes an important topic (e.g., Uber monitoring surveillance system [5]; Amazon’s AI recruitment tool biased against women [6, 7]).

Scholars have highlighted the transformative impact of such technological deployment in the workplace [2, 8,9,10]. Digital technology in the workplace notably reshapes employment relationships, calling into question traditional work cultures related to the place and nature of work, the type of surveillance, and more broadly, the organisation and management of the work activities [11, 12]. Despite these disruptive aspects, new digital technologies may also be deployed for positive purposes such as occupational safety and health (OSH), which can also be a legal obligation for employers. Examples include the development of protective clothing like smart personal equipment [13, 14], AI devices for the well-being of employees in office jobs including smart watches in corporate wellness programmes [15], or emotion-sensing technologies for stress detection [16]. But, whenever biosensors connected through AI systems are deployed in the workplace, it does not remove concerns regarding privacy [17] or a blurring effect between using technology for OSH purposes and employee evaluations [18].

The aim of this paper is to address the question of how to guarantee that AI systems for OSH are deployed in a human-centric approach, meaning with the goal of improving welfare and freedom. Considering that law is one of the key requirements to achieve such a goal, there is a need to identify the main concerns raised by the use of digital technologies for OSH purposes and to determine the adequacy of legal requirements to address these concerns. While this concerns both the private and public sector, the latter is subject to more stringent legal requirements for its decisions, which must directly respect human rights and principles of good administration. The paper also informs policymakers of the risks related to the promotion of digital solutions for occupational health when they are mainly focused on the risks related to the increasing deployment of AI and digital technologies regarding the algorithmic management [19,20,21,22,23].

The paper is structured as follows: First, we begin with a background on OSH and how AI systems can contribute to such a public purpose. Next, we present our approach to explore this complex problem from a dual point of view: law and ethics. We then outline the European legal framework and elaborate on three scenarios regarding the deployment of IoT for the purpose of OSH, highlighting the major ethical issues. In light of these scenarios, we discuss the possible legal responses to the identified ethical challenges, thereby pinpointing important blind spots that need to be addressed. Considering the states’ direct obligations to respect, protect, and fulfil human rights, we conclude that it is important to encourage the public sector, in its leadership role, to assess the potential impact on these human rights and set up necessary safeguards before favouring the deployment of an AI system for an occupational health public policy purpose.

2 Background

2.1 Maintaining the Safety and Health of Employees

‘Occupational accidents and diseases create a human and economic burden’ [24] and lead to a political response with the recognition of individual workers' rights [25], enshrined in international human rights lawFootnote 1. In 1950, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a common definition of OSH, considering ‘its ultimate goal as the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations’ [26]. The concept of well-being in occupation was also defined as ‘relate(d) to all aspects of working life, from the quality and safety of the physical environment, the climate at work and work organization’. The measures taken to ensure well-being in the workplace shall then be consistent with those of OSH ‘to make sure workers are safe, healthy, satisfied and engaged at work’. In this perspective, OSH deals with the ‘anticipation, recognition, evaluation and control of hazards arising in or from the workplace that could impair the health and well-being of workers, taking into account the possible impact on the surrounding communities and the general environment’ [27].

The protection and promotion of safety and health involves the development of national public policy. To assist States in developing such a policy, the ILO has adopted a series of conventions, recommendations and guides [27].Footnote 2 From this perspective, employers have a duty to protect workers from and prevent occupational hazards, but also to inform workers on how to protect their health and that of others, to train their workers, and to compensate them for injuries and illnesses [27]. In the European Union context, based on article 153(2) TFEU, the directive 89/391/EEC of June 12, 1989, addresses measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work. Its scope of application concerns the private and public sectors. The employer's obligations are part of a preventive approach [28]. In this respect, the directive requires that States take measures to ensure that the employer assesses the risks, evaluates those that cannot be avoided, combats them at the source, adapts the work to the individual or develops a coherent prevention policy covering technology, working conditions, social relations and the influence of health-related factors. In addition, when the employer introduces new technologies, they must be subject to consultation with the workers and/or their representatives about the consequences of the choice of equipment, working conditions and environment on the safety and health of the workers. The preventive approach promoted to achieve OSH involves an assessment of the risks that rise in the course of work, which may be related to the use of a new technology.

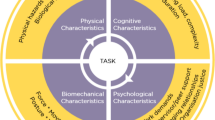

2.2 AI Systems for Occupational Safety and Health

Data-driven health initiatives are gaining interest among employers to improve OSH through monitoring and tracking employees in the workplace [29]. These initiatives rely on the deployment of AI systems that are a combination of software and hardware that enable data capture and analysis to achieve a certain outcome. Among the building blocks of AI systems is the IoT technology. IoT enables access to various types of data in a cyber-physical system. Combined with machine learning algorithms, IoT applications form AI systems that allow the collection and analysis of physical data in the aim of providing actionable insights. With the rapid development of ubiquitous IoT devices, IoT initiatives are being used for self-quantifying and digital monitoring to detect and prevent health issues and to mitigate health risks [30].

In fact, organisations employ these technologies to collect data related to health, fitness, location and emotions [31, 32]. Wearable technology is most prominently used for such purposes. It includes smart accessories (e.g., smart watches and smart glasses) and smart clothing (e.g., smart shirts and smart shoes) that can record physiological and environmental parameters in real-time, perform analysis to the data, and provide insights to the users in the form of nudges or interventions [33]. Moreover, sensor networks can be placed in different places and are commonly used to detect ambient conditions such as temperature, air quality or occupancy [34, 35]. IoT is used in the workplace for physical health monitoring, either through addressing physical inactivity/sedentary behaviour or poor postures that cause musculoskeletal disorders [36].

In addition, AI systems employing IoT enable emotional health monitoring through detecting occupational stress or burnouts that can affect the health of employees and compromise the quality of work in the long run. This can be achieved through the measurement of biomedical data including heart rate and body temperature for an estimation of emotional levels, most commonly through wearables [37, 38] or facial and speech recognition techniques [39]. These systems assess the employee’s state and provide suggestions for healthier habits based on the analysed data. Moreover, environmental monitoring is another use case for IoT employing sensors (e.g., temperature and humidity) for detecting abnormalities and optimal ambient conditions [40, 41].

Risks associated with the deployment of such technologies in the workplace are then the continuous personal and contextual data collection [42] and its tracking effect [43], information or hidden insights about the employee [44] and the potential bias [45, 46].

3 Research Approach

Considering that the development and deployment of technologies raises new questions for society, we adopt a transdisciplinary ethical and legal approach. From a law perspective, since we were interested in questions related to what ought to be [47] and in the novelty of such digital deployment, we decided to focus on leading institutions in the field of regulation of new technologies and protection of individuals, namely the European Union and the Council of Europe. We collected legal sources through official publication websites of both organisations (EUR-Lex and HUDOC). We used several keywords (occupational health, artificial intelligence, worker’s right to data protection, data protection law) for collecting authoritative texts produced by legislators (legislation) and judges (case-law) [48]. The legal analysis was conducted by two authors.

For the ethical analysis, we collected data on experts’ perceptions on OSH digital solutions during a workshop that took place in December 2021, including ten stakeholders with various expertise (technology, medicine, public administration, politics and ethics). Participants had more than five years of experience within their respective field. During the discussion, we presented to participants three scenarios describing the deployment of IoT and AI systems for a typical OSH purpose. We have built these scenarios based on a review of literature on existing solutions for OSH in office settings. The objective of the workshop was to discuss the acceptability, benefits and ethical issues or risks that could be associated to the deployment of these solutions in the workplace. We took the necessary measures to safeguard the confidentiality of participants’ inputs. A preliminary data screening of the discussionFootnote 3 was operated by two authors. Our examination was based on the four ethics principles – respect to human autonomy, prevention of harm, fairness and predictability – identified and defined by the Ad hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence (CAHAI) [19]. This analysis helped us to highlight specific concerns raised by the deployment of the new technologies for OSH purposes. In a second stage, we used the technique of subsumption applied in legal interpretation: we linked the four main concerns that we have identified to existing legal rules in order to assess whether those rules provide satisfactory responses. In the case of failure, it means that we have identified blind spots in which laws do not provide clear or satisfying answers to relevant ethical concerns.

4 Legal Framework About AI Systems in the Workplace

The discussion on new technologies has largely focused on the erosion of privacy produced by the indiscriminate processing of data. The technology sophistication goes and will go beyond the question of data privacy and there is a political will to regulate AI systems and their use in the workplace. These two fields need to be investigated.

4.1 Regarding Privacy

The surveillance inherent in the employment relationship cannot neglect the employees’ right to privacy. Various institutional sources show that workers’ data should be treated with caution. First, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that article 8 protects the employee in the performance of his professional duties, thus establishing a limit to the principle of surveillance in employment relationships.Footnote 4 It also recognised that between employer and employee’s rights, the States have the obligation to balance the interests.Footnote 5 If the intrusion is aimed at remedying an employee's behaviour that is detrimental to the employer, the intrusion can be justified through proportionality.Footnote 6 The legal nature of the employer also has a consequence on the nature of the obligations of the state.Footnote 7 In the case of public organisations, the European Court of Human Rights also ruled that the public actor is directly bound by the conditions for public interference with an individual right, namely the requirement of a legal basis, the public interest and the principle of proportionality.Footnote 8

Moreover, and in accordance with Convention 108 +, any personal data processing by public sector authorities should respect the right to private life and comply with the ‘three tests’ of the principle of proportionality: lawfulness, legitimacy and necessity. The lawfulness test implies checking not only if there is a legal basis but also that such a legal basis is ‘sufficiently clear and foreseeable’. In the M.M. case, the Court indicated that: ‘the greater the scope of the recording system, and thus the greater the amount and sensitivity of data held and available for disclosure, the more important the content of the safeguards to be applied at the various crucial stages in the subsequent processing to date’.Footnote 9 The test of legitimacy implies that personal data undergoing automatic processing must be collected for explicit, specified and legitimate purposes, such as national security, public safety and economic well-being. Finally, the test of necessity includes five requirements: minimization of the amount of data collected; accuracy and updating of data; limiting the data process and storage to what is necessary to fulfil the purpose for which they are recorded, limiting the use of data to the purpose for which they are recorded; and transparency of data processing procedures.

All these requirements for data processing are also enshrined in the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679, GDPR). In the context of employment, the collection and processing of sensitive data for OSH is possibleFootnote 10. The GDPR also authorises member states to specifically regulate the processing of data. National legislations can cover the ‘recruitment, performance of employment contracts, management, planning and organization of work, equality and diversity in the workplace, health and safety at work, protection of employer's or customer's property and for the purposes of the exercise and enjoyment of social benefits in the course of employment or after the termination of the employment relationship’Footnote 11. Nevertheless, member states must include in their national provisions suitable and specific measures to safeguard the data subject’s human dignity, legitimate interests and fundamental rights, with particular regard to the transparency of processing, the transfer of personal data within a group of undertakings, or a group of enterprises engaged in a joint economic activity and monitoring systems in the workplace.

Finally, the ILO recommendation No. 171 of 1985 provides that OSH services should record data on workers’ health in confidential medical files. Persons working in the service should only have access to these records if they are relevant to the performance of their own duties. If the information collected includes personal information covered by medical confidentiality, access should be limited to medical staff. It is also provided that personal data relating to health assessment may only be communicated to third parties with the informed consent of the worker concerned. The ILO adopted in 1997 a set of practical guidelines on the protection of workers’ personal data and in its 2008 position paper, it recalled that ‘provisions must be adopted to protect the privacy of workers and to ensure that health monitoring is not used for discriminatory purposes or in any other way prejudicial to the interests of workers’ [27].

4.2 Future Legal Developments Regarding AI Systems

New digital innovation generates new risks. In the context of the European Union, the legislator wants to maintain the balance between the protection of fundamental rights and the economy. For this purpose, a legislative proposal on AI systems is under discussion. It already offers some insights about how employers could tackle legal issues. At this stage, only the explanatory comments announced to pursue ‘consistency with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the existing secondary Union legislation on data protection, consumer protection, non-discrimination and gender equality’. The proposal is presented to complement the current legal framework with ‘a set of harmonized rules applicable to the design, development and use of certain high-risk AI systems and restrictions on certain uses of remote biometric identification systems.’ It also completes existing Union law on non-discrimination with specific requirements that aim to minimise the risk of algorithmic discrimination, in relation to the design and the quality of data sets used within the AI systems.

Moreover, safety and health are seen as possible outcomes of AI systems. Those are viewed as potential solutions to the problem of work-related health. Nevertheless, annex III for high-risk AI systems includes systems that involve ‘employment, workers management and access to self-employment’, those operating for recruitment purposes and within ‘contractual relationships, for task allocation and monitoring and evaluating performance and behaviour of persons in such relationships.Footnote 12 At this stage of the legislative discussion, it is not clear if AI systems for OSH would be considered. They are not expressly listed, but they could be indirectly helpful to define the task allocation in the workers management.

5 Ethical Considerations of AI Systems for OSH

5.1 Scenarios

For the workshop discussion, we presented three scenarios describing the deployment of digital technologies for promoting the health of employees and improving their working conditions. Each scenario describes a different context of implementation of a different device or technology that collects employees’ health-related data and output reports. The scenarios vary with respect to what type of health data are collected (posture on a chair, step count, voice tone, etc.), how the device is proposed to employees (consultation, information or opt-out options), how the data is managed (e.g., sent to external companies or not) and processed (e.g., results anonymised or not), and who receives the report (employees, occupational physician or human resources).

Scenario 1: Smart Chairs for Monitoring Sedentary Behaviour

The first scenario discusses the use of smart chairs to avoid chronic illnesses resulting from employees’ posture while working. These smart chairs detect poor neck, head and back postures and a red light switches on whenever its user rests in this posture for several minutes. They also produce a light sound as a nudge to inform users when they remain seated for a prolonged period. The smart chairs are designed with a programme that stores data about users’ posture and sitting time and generates individual reports including health advice.

Scenario 2: Steps Contest in a Corporate Wellness Programme

The second scenario discusses a steps contest initiative within a corporate wellness programme that aims to motivate employees to engage in more physical activity for the benefit of their health. Employees’ steps are monitored by smartwatches provided by the company to all employees willing to participate. The smartwatches monitor users’ steps, speed of motion, heart rate, body temperature and blood pressure. On a comprehensive app user interface, participants can access personalised reports of their step performance, general activity and physical health metrics and rankings.

Scenario 3: Stress Monitoring and Management

The third scenario discusses the use of sensor networks in order to assess employees’ satisfaction with the flexible work policy and stress levels related to their working conditions and workload. Computers used by the employees are equipped with sensors capturing speech tone and speed (disregarding content). Information collected by the sensors are processed by deep learning algorithms, which output an assessment of individual stress levels and emotional state. These algorithms produce real-time signals and recommendations to employees (such as “It may be the right moment for a break”). Also, reports of overall stress levels are sent periodically to the employees who are encouraged to share them with their direct supervisors as a basis for discussing their satisfaction with the working conditions and workload.

5.2 Ethical Considerations

Based on the inputs provided by the stakeholders’ discussion, we identified a series of ethical concerns emerging in the three scenarios. One major issue that we identified is trust in the technology and in its intended and actual use by the employer. A linked topic is the question of ensuring that the technology is the right answer to the right problem. For instance, is the smart chair an appropriate response to employees’ back pain or shouldn’t other organisational changes (working schedule or changes of working tasks) be made to meet the same aim more efficiently? Additionally, what is the employer’s real intention in deploying such a technology? Indeed, despite the fact that the three scenarios represent cases of monitoring for health improvement, it cannot be ignored that these tools and the data they collect could be used for other purposes. Moreover, these tools are also intended to be nudging mechanisms. Is such an incentive to behave in a certain way likely to have negative consequences for workers who refuse to comply? For example, in the smart chair scenario, can employees be held responsible for back pain they could have avoided? Could they be deprived of social protection? In light of the AI ethical principles developed by the CAHAI, these elements mainly reflect the requirement of fairness and, secondarily, that of preventing (indirect) harm.

A second major issue encountered in the three scenarios is the tension between employee choice and employer power. In fact, even if consent from employees is required for deploying the technology, the consent provided may not be freely obtained, and therefore ill-founded. Indeed, in some working environments, employees may feel pressured to comply in order to avoid discrimination or other forms of sanctions resulting from their refusal to opt into the new system. In addition, financial incentives may influence employees’ judgment (e.g., the provision of smartwatches in the second scenario), which may be seen as a form of indirect pressure to participate since a reward is involved, thus intensifying the power imbalance within the organisation. All these elements raise the issue of respecting the employees’ autonomy in the employment relationship (respect for human autonomy).

A further important concern is the risk of discrimination. This is mainly associated with the use of special devices and algorithmic decision-making. In fact, the main question is how to guarantee the accuracy of the devices in collecting the data and the algorithmic correctness. Biased source data or algorithms implemented in the AI system might generate discriminatory downstream decisions. This issue is particularly worrisome in the case of systems implemented for OSH purposes; the collected data often include health information, location and behaviour. These types of data can easily be reused to assess employees’ working capacities and capabilities, which are key factors used for deciding to promote or fire employees. Here again, these issues echo the principles of fairness and prevention of harm.

Privacy is also a central concern when it comes to collecting and processing personal data. In the three scenarios, the employer owns the systems used in the workplace, but data generated is managed and processed by third parties in most cases. Thus, the worker has no or limited control over the data collection, use and sharing, which creates a problem for privacy. Moreover, privacy risk increases with extensive data collection. This concern is particularly relevant when sensitive health data are collected.

Another issue is employer surveillance. This issue is also connected to the topic of the intended purpose or use of the system deployed. As mentioned earlier, even though the technology may be implemented for OSH, it may provide data relevant for monitoring work performance or other business relevant factors. If workers are aware of such forms of dual uses, it can create a chilling effect, and influence their behaviour. Workers who know that they are monitored might change their working pace or methods in order to approach social conformity. Surveillance becomes an even more problematic issue when it is extended to employee’s homes. Flexible work policy and remote working creates new challenges which are illustrated in our second and third scenarios. When a wearable device for health monitoring is proposed to employees, it means that they will be monitored all day and the data collected corresponds with their physical activity and health status at work and in their private life. When a system is deployed in an at-home setting, private interactions at home are also monitored. These are only two examples of surveillance that trespass the privacy of others (i.e., extrinsic privacy). All these elements regarding privacy and employer surveillance further underline the principles of prevention of harm and fairness.

6 Discussion

Our overview of the extended legal framework that applies to OSH digital solutions provides a range of information regarding the obligations of employers when they purpose to collect data on their employees. Our ethical analysis, based on inputs from the workshop discussion and on the application of a four principles framework helped us to identify ethical issues and group them in relevant categories. In this section, we will assess the adequacy of the legal framework for addressing four main issues that we have identified.

The trust concern is about the digital solution and its user (the employer). To ensure that the benefits and costs are balanced with fairness, European law contains the proportionality principle which involves determining whether the means is adequate to achieve the desired end. This principle is also at the foundation of public decisions of liberal and democratic states. For public employers, it means verifying the effectiveness of digital devices to address the public health problem. The legitimacy principle is also useful to address the question of an unintended use of the device which could, by ricochet, violate the data purpose principle of the GDPR.Footnote 13 Respecting the intended use of the device is also expressed in the AIA proposal.Footnote 14

The trust concern is also a question of information. From this perspective, it is linked to the explicability principle. In terms of legal requirements, it can be addressed with the right to information which is a fundamental right for workers and a common requirement of several pieces of legislation. The OSH directive provides a general obligation to the employer for ensuring ‘information and instructions (…) in the event of introduction of any new technology’ (art.12).Footnote 15 Employers must also inform and consult employees and/or their representativesFootnote 16. The GDPR requires that any data process shall be operated in respect of the transparency principle.Footnote 17 The AIA proposal should reinforce this transparency principle.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, in the AIA proposal, such an obligation is limited to the AI providers, not the users, and in the case of high-risk AI systems in which OSH initiatives do not seem engaged.

The autonomy concern echoes the human autonomy principle. Once more, several legal regulations also enshrine such an ethical principle. From human rights law, it is embedded in the right to personal life. If technology has an individual impact, it must be analysed as limiting the individual autonomy. In such a case, public employers shall respect the principle of proportionality and proceed to the three tests of lawfulness, legitimacy and necessity. In the GDPR, the autonomy concern is related to the consent requirement. On this point, both the European data protection authority and legal scholars [49, 50] agree that, in the working environment, consent could not be considered free and informed. For this, a legal basis for the processing of data is necessary. The field of OSH is precisely a legitimate purpose.Footnote 19

Regarding the discrimination concerns, it appears at two levels: in the data set and through the outcomes of the device. At these two levels, the use of a digital solution can generate unfairness practices. To begin, the quality of the data set is of particular importance (i.e., relevance, representativity, completeness and correctness). The AIA should directly address this question of bias in the data set. It will be an obligation for providers who will have to process special categories of data such as health or biometric in a way that ensures the detection, correction and erasure of bias in notably high-risk AI systemsFootnote 20. Nevertheless, public employers as users of AI systems are also directly obliged to respect the principle of equality between individuals. If they use a system that leads to discrimination, they can subsequently be held liable for the damage that results from this discrimination. Regarding the discrimination risk as a result of the outcomes of the devices, it echoes the problem of a chilling effect, which happens when ‘people might feel inclined to adapt their behaviour to a certain norm’. Technology is likely to influence individuals to change their behaviour without them even being aware of it. In this perspective, technology can be viewed as problematic regarding the right to individual self-determination. At this stage, there is no legal guarantee that employees will be protected against such a phenomenon, despite it being viewed as one of the major concerns in the 2020 report of the CAHAI [19].

The last concern is employee privacy, which was related to the blurring effect between professional and personal life. In law, the protection of privacy is guaranteed under the right to the protection of personal data. At an operational level, it means that employers must minimise data collection, limiting it to health purposes, and finally destroy such data. However, compliance with the minimisation and purpose requirement may be particularly challenging to achieve if the device cannot discriminate between data produced by other users - for example, family members - who would also have access to these tools within the family. Moreover, such digital solutions are generally developed by business enterprises that continue to play a role in the data storage and analysis. In such a situation, public employers must also respect their obligations towards such stakeholders. Finally, if the digital device targets the recognition of micro-expressions, voice tone, heart rate and temperature to assess or even predict our behaviour, mental state and emotions, it must be considered as an intrusive tool that collects biometric data and, in the future, should fall under annex III of the AIA.Footnote 21 Moreover, at this stage, there is a legal gap. As mentioned by the CAHAI report, biometric data used for an aim other than recognition, such as categorization (for example, for the purpose of determining insurance premium based on statistical prevalence health problems), profiling, or assessing a person’s behaviour, might not fall under the GDPR definition. The GDPR only considers automating the processing of data, but not regarding behaviour prediction based on data processing.

This general legal assessment of the ethical concerns shows that the European law does not offer an answer to all the problems identified by our ethical analysis. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the components of the principle of proportionality appear several times and can be mobilised as preliminary test before deploying OSH digital solutions.

7 Conclusion: Proposal for Social and Human Rights Assessment

This paper discusses the question of how to guarantee a deployment of AI systems for OSH in the public sector in a human-centric approach. In this context, we focused on OSH digital tools. Even if deployed for good purposes, the use of those systems does not exclude complex ethical issues. First, we have shown that AI systems are not deployed in a legal vacuum. They have to meet initial requirements. However, they may generate problems that are sometimes not directly identifiable or have not been taken into account from a legal point of view. To map these problems, we used an inductive approach which helped us to identify a series of ethical concerns regarding the implementation of AI systems for OSH. Further we examined whether the law imposes duties and rights in such situations. We found that legal answers were sometimes insufficient, leaving room for manoeuvre for the user of the AI system and risks for the employees. Therefore, such a conclusion forces us to ask what solution could be promoted to ensure that the use of this type of digital tool is firmly anchored in the respect of the weakest party (the employee) and in the protection and promotion of his or her health.

Other avenues should still be explored considering the AI systems’ rapid deployment. From a practical point of view, one may wonder whether the logic of subsumption followed in Sects. 5 and 6 is not already an initial way of proceeding to assess the appropriateness of deploying an AI system. It makes it possible to link an empirical assessment to a legal analysis, including the various proportionality tests. The data protection impact assessment (DPIA), imposed by the GDPR, is a practical tool to assess the privacy risks for data processing technologies (including AI systems), where the realisation of data processing principles is controlled with respect to dedicated safeguards within the deployment of new technologies [51]. This type of assessment is one compliance tool to law, which could help in demonstrating accountability. However, as we have seen, the GDPR does not cover all risks related to technological innovations and its DPIA is therefore limited in scope. In line with [52], we believe that an ethical impact assessment could complement the DPIA of new technologies imposed by law to ensure the adequate examination of ethical considerations of different stakeholders before and during the deployment of new technologies. To address that, in [53, 54], the authors call for social and human impact assessment, and in [55] developed a gold standard for discrimination assessment. We, therefore, suggest a more inclusive approach to the assessment, that includes a social and human rights impact assessment with stakeholders that should focus on methods and procedures for identifying ethical concerns and respecting public values. Such an approach would be necessary to mitigate risks and address the identified concerns within a continuously evolving digital sphere. To this end, it therefore requires further research. Finally, in the framework of OSH public policy, all these proposals should also be examined as solutions for preliminary assessment of AI systems' deployment.

Notes

- 1.

Several international texts expressed their commitment for the protection of safety and health of the workers: the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (art. 23); the 1966 Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (art. 7); and the European Social Charter, adopted in 1961 and revised in 1996 (right to safe and healthy working conditions (art. 3), right to health protection (art. 11), obligation to improve work conditions and environment (art. 22).

- 2.

The ILO Convention, 1981 (No. 155) and its Recommendation (No. 164); the ILO Convention, 1985 (No. 161) and its Recommendation (No. 171); and the ILO Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 187) and Recommendation (No. 197).

- 3.

In addition to the workshop, we conducted a series of individual interviews with a diversified panel of stakeholders. A detailed qualitative analysis is undergoing and will be published in a separate paper.

- 4.

ECtHR, Niemietz v. Germany, n°13710/88, 16 December 1992, §§33–34. The Court ruled that ‘respect for private life comprised to a certain degree the right to establish and develop relationships with others. There was no reason of principle why the notion of ‘private life’ should be taken to exclude professional or business activities, since it is in the course of their working lives that the majority of people had a significant opportunity of developing such relationships. To deny the protection of Art. 8 on the ground that the measure complained of related only to professional activities could lead to an inequality of treatment, in that such protection would remain available to a person whose professional and non-professional activities could not be distinguished’.

- 5.

ECtHR, Copland v.UK, n°62617/00, 3 April 2007.

- 6.

ECtHR, Lopez Ribalda and Others v. Spain (GC), n°1874/13 and 8567/13, 17 October 2019, §§ 118, 123.

- 7.

ECtHR, Bărbulescu v. Romania (GC), n°61496/08, 5 September 2017, §108.

- 8.

ECtHR, Libert, 22 February 2018, n°588/13; Renfe c. Espagne (déc.), n°35216/97, 8 September 1997 and Copland (mentioned above, §§ 43–44).

- 9.

ECtHR, M.M. v. UK, 13 November 2012, n°24029/07, §200.

- 10.

GDPR, art. 9.2(h).

- 11.

See also recital 155.

- 12.

Annex III; recital 36.

- 13.

Art. 6 GDPR concerning the lawfulness of the processing; See also art. 9 GDPR concerning the processing of special categories of personal data such as health data; See art. 88 in the context of processing in the context of employment; See recital 50 of the GPDR on the initial link between the purposes for which the data have been collected and the purposes of the intended further processing.

- 14.

The intended purpose principle, as defined in art.3(12), is mentioned 37 in the AIA proposal and is at the core of the regulation. Requirements (recital (43) and assessment of the risks are assessed at the light of the intended purpose of the system (Recital (42)) and new conformity assessment occurs when the intended purpose of the system changes (recital 66).

- 15.

Art. 12. 1 OSH Directive.

- 16.

Art. 6.3 (c) OSHA directive.

- 17.

Art. 12 GDPR.

- 18.

Art. 13.3 AIA proposal.

- 19.

Art. 9. 2 (h) GDPR; art. 6 OSH directive.

- 20.

Recital 44 AIA proposal.

- 21.

The CAHAI report underlines that there is no sound scientific evidence corroborating that a person’s inner emotions or mental state can be accurately ‘read’ from a person’s face, heart rate, tone or temperature.

References

Lodovici, S., et al.: Teleworking and digital work on workers and society. Special focus on survaillance and monitoring, as well as on mental health of workers. European Parliament (2021)

Moore, P., Piwek, L.: Regulating wellbeing in the brave new quantified workplace. Empl. Relat. 39, 308–316 (2017)

Lee, M.K., Kusbit, D., Metsky, E., Dabbish, L.: Working with machines: the impact of algorithmic and data-driven management on human workers (2015)

Kaoosji, S.: Worker and community organizing to challenge amazon’s algorithmic threat. In: Alimahomed-Wilson, Ellen, J.R. (eds.) The Cost of Free Shipping, pp. 194–206. Pluto Press (2020)

de Chant, T.: Uber asked contractor to allow video surveillance in employee homes, bedrooms: employee contract lets company install video cameras in personal spaces. Ars Technica (2021)

Dastin, T.: Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters (2018)

Manokha, I.: New means of workplace surveillance. Monthly Review, vol. 70 (2019)

Ajunwa, I., Crawford, K., Schultz, J.: Limitless Worker Surveillance. Calif. Law Rev. 105, 735–776 (2017)

Aloisi, A., Gramano, E.: Artificial intelligence is watching you at work. digital surveillance, employee monitoring, and regulatory issues in the EU context. Spec. Issue Comp. Labor Law Policy J. 41, 95–122 (2019)

Hendrickx, F.: From digits to robots: the privacy-autonomy nexus in new labor law machinery. Comp. Lab. Law Policy J. 40, 365–388 (2019)

Aloisi, A., De Stefano, V.: Essential jobs, remote work and digital surveillance: addressing the COVID-19 pandemic panopticon. Int. Lab. Rev. 161, 289–314 (2022)

Aloisi, A., Gramano, E.: Artificial intelligence is watching you at work: digital surveillance, employee monitoring, and regulatory issues in the EU Context. Comp. Lab. L. Pol’y J. 41, 95 (2019)

Thierbach, M.: Smart personal protective equipment: intelligent protection for the future. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (2020)

Kim, S., et al.: Potential of exoskeleton technologies to enhance safety, health, and performance in construction: industry perspectives and future research directions. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 7, 185–191 (2019)

Burke, R., Richardsen, A.: Corporate Wellness Programs. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham (2014)

Whelan, E., McDuff, D., Gleasure, R., Vom Brocke, J.: How emotion-sensing technology can reshape the workplace. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 59(3), 7–10 (2018)

Collins, P.M., Marassi, S.: Is that lawful?: Data privacy and fitness trackers in the workplace. Int. J. Comp. Lab. Law 37, 65–94 (2021)

Akhtar, P., Moore, P.: The psychosocial impacts of technological change in contemporary workplaces, and trade union responses. Int. J. Lab. Res. 8, 101–131 (2016)

CAHAI - Ad hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence: Towards a Regulation of AI Systems: Global perspectives on the development of a legal framework on Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems based on the Council of Europe’s standards on human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Ad Hoc Committee on Artificial Intelligence, Council of Europe (2020)

Independent High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence: Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI, Publications Office, 2019. European Commission (2019)

Vaele, M., Borgesius, F.Z.: Demystifying the draft EU artificial intelligence Act analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Comput. Law Rev. Int. 22(4), 97–112 (2021)

Ebers, M., Hoch, V.R.S., Rosenkranz, F., Ruschemeier, H., Steinrötter, B.: The european commission’s proposal for an artificial intelligence act—a critical assessment by members of the robotics and AI law society (RAILS). Multi. Sci. J. 4, 589–603 (2021)

Tan, Z.M., Aggarwal, N., Cowls, J., Morley, J., Taddeo, M., Floridi, L.: The ethical debate about the gig economy: a review and critical analysis. Technol. Soc. 65, 101594 (2021)

ILO: Builidinf a preventive safety and health culture. A guide to the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (n°155), its guide Protocole and the Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (n°187). (2013)

Abrams, H.K.: A short history of occupational health. J. Public Health Policy 22, 34–80 (2001)

Organisation, I.L.: ILO standards-related activities in the area of occupational safety and health: an in-depth study for discussion with a view to the elaboration of a plan of action for such activities. In: Office, L. (ed.), Geneva (2003)

Alli, B.O.: Fundamental Principles of Occupational Health and Safety. International Labour Organization, Geneva (2008)

Raworth, P.: Regional harmonization of occupational health rules: the European example. Am. J. Law Med. 21, 7–44 (1995)

Charitsis, V.: Survival of the (data) fit: Self-surveillance, corporate wellness, and the platformization of healthcare. Surveill. Soc. 17, 139–144 (2019)

Yassaee, M., Mettler, T., Winter, R.: Principles for the design of digital occupational health systems. Elsevier (2019)

Manokha, I.: The implications of digital employee monitoring and people analytics for power relations in the workplace. Surveill. Soc. 18, 540–554 (2020)

Giddens, L., Leidner, D., Gonzalez, E.: The role of Fitbits in corporate wellness programs: does step count matter?. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp. 3627–3635, Hawaii (2017)

Fdez-Arroyabe, P., Fernández, D.S., Andrés, J.B.: Work environment and healthcare: a biometeorological approach based on wearables. In: Dey, N., Ashour, A.S., James Fong, S., Bhatt, C. (eds.) Wearable and Implantable Medical Devices, vol. 7, pp. 141–161. Academic Press (2020)

Afolaranmi, S.O., Ramis Ferrer, B., Martinez Lastra, J.L.: Technology review: prototyping platforms for monitoring ambient conditions. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 28, 253–279 (2018)

Saini, J., Dutta, M., Marques, G.: A comprehensive review on indoor air quality monitoring systems for enhanced public health. Sustain. Environ. Res. 30, 6 (2020)

Gorm, N., Shklovski, I.: Sharing steps in the workplace: changing privacy concerns over time. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 4315–4319, San Jose (2016)

Han, L., Zhang, Q., Chen, X., Zhan, Q., Yang, T., Zhao, Z.: Detecting work-related stress with a wearable device. Comput. Ind. 90, 42–49 (2017)

Stepanovic, S., Mozgovoy, V., Mettler, T.: Designing visualizations for workplace stress management: results of a pilot study at a swiss municipality. In: Lindgren, I., et al. (eds.) EGOV 2019. LNCS, vol. 11685, pp. 94–104. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27325-5_8

Fugini, M., et al.: WorkingAge: providing occupational safety through pervasive sensing and data driven behavior modeling. In: Proceedings of the 30th European Safety and Reliability Conference, pp. 1–8, Venice (2020)

Nižetić, S., Pivac, N., Zanki, V., Papadopoulos, A.M.: Application of smart wearable sensors in office buildings for modelling of occupants’ metabolic responses. Energy Buildings 226, 110399 (2020)

van der Valk, S., Myers, T., Atkinson, I., Mohring, K.: Sensor networks in workplaces: correlating comfort and productivity. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing (ISSNIP), pp. 1–6. IEEE (2015)

Souza, M., Miyagawa, T., Melo, P., Maciel, F.: Wellness programs: wearable technologies supporting healthy habits and corporate costs reduction. In: Stephanidis, C. (ed.) HCI 2017. CCIS, vol. 714, pp. 293–300. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58753-0_44

Hall, K., Oesterle, S., Watkowski, L., Liebel, S.: A literature review on the risks and potentials of tracking and monitoring eHealth technologies in the context of occupational health management (2022)

Gaur, B., Shukla, V.K., Verma, A.: Strengthening people analytics through wearable IOT device for real-time data collection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Automation, Computational and Technology Management, pp. 555–560. IEEE, London (2019)

Feuerriegel, S., Dolata, M., Schwabe, G.: Fair AI: challenges and opportunities. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 62, 379–384 (2020)

Siau, K., Wang, W.: Building trust in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and robotics. Cutter Bus. Technol. J. 31, 47–53 (2018)

Tyler, T.R.: Methodology in legal research. Utrecht L. Rev. 13, 130 (2017)

Langbroek, P.M., Van Den Bos, K., Simon Thomas, M., Milo, J.M., van Rossum, W.M.: Methodology of legal research: challenges and opportunities. Utrecht Law Rev. 13, 1–8 (2017)

WP29: Opinion 2/2017 on data processing at work. In: Party, A.D.P.W. (ed.) (2017)

Brassart Olsen, C.: To track or not to track? Employees’ data privacy in the age of corporate wellness, mobile health, and GDPR. Int. Data Priv. Law 10, 236–252 (2020)

Wagner, I., Boiten, E.: Privacy risk assessment: from art to science, by metrics. In: Garcia-Alfaro, J., Herrera-Joancomartí, J., Livraga, G., Rios, R. (eds.) DPM/CBT -2018. LNCS, vol. 11025, pp. 225–241. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00305-0_17

Wright, D., Mordini, E.: Privacy and ethical impact assessment. In: Wright, D., De Hert, P. (eds.) Privacy impact assessment, pp. 397–418. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2543-0_19

Jasanoff, S.: The ethics of invention: technology and the human future. W.W. Norton & Company, New York (2016)

Metcalf, J., Moss, E., Watkins, E., Singh, R., Elish, M.C.: Algorithmic impact assessments and accountability: the co-construction of impacts. In: ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’21). ACM, Canada (2021)

Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., Russell, C.: Why fairness cannot be automated: bridging the gap between EU non-discrimination law and AI. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 41, 72 (2021)

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 187429) within the Swiss National Research Programme (NRP77) on “Digital Transformation”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper

Weerts, S., Naous, D., Bouchikhi, M.E., Clavien, C. (2022). AI Systems for Occupational Safety and Health: From Ethical Concerns to Limited Legal Solutions. In: Janssen, M., et al. Electronic Government. EGOV 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13391. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15086-9_32

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15086-9_32

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15085-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15086-9

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)