Abstract

This article reviews health beliefs, and attitudes of asylum seekers and refugees, using an adapted framework of the Health Belief Model. The systematic review included 15 peer-reviewed records retrieved from CINAHL, Medline, PubMed, PsycINFO, and PsycArticles. Findings of this review show culture, tradition, fate or destiny, psychological factors, family, friends, and community were crucial influential factors in shaping asylum seekers, and refugees’ perceived barriers, fear, severity, and susceptibility in their health-seeking activities. In addition, knowledge and awareness related to the benefits of using modern healthcare services were motivators for different ethnic groups to take care of their personal health. Healthcare providers, educational programs, and support from family, friends, and community had noteworthy influence on triggering the health-related decision-making process among asylum seekers and refugees. This study offers practical implications for healthcare providers and public health community to devise culturally relevant strategies that will effectively target asylum seekers and refugees with diverse cultural, traditional and attitudinal beliefs about healthcare and health seeking activities. This is one of the descriptive review studies on asylum seekers and refugees’ health beliefs and their health-seeking behavior based on ethnicity grounds.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the recent decades, healthcare providers have investigated the health needs of refugeesFootnote 1 and asylum seekersFootnote 2. Still, since healthcare providers deal with vulnerable people, it is important to consider providing health services that are culturally adopted for minorities with diverse ethnic backgrounds [3]. Studies on resettled asylum seekers and refugees in a new country indicated different issues related to the healthcare, such as insufficient healthcare attention because of organizational barriers, cultural differences, language barrier, and access to social or healthcare services [3,4,5,6].

Moreover, refugees and asylum seekers may find it difficult to adapt to new environments and lifestyle, resulting in emotional and psychological issues [7,8,9]. Even though, it is expected migration influences value changes during adaptation, asylum seekers and refugees might continue with their own cultural practices to maintain their health and well-being, as health beliefsFootnote 3 typically do not change after migration [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Health beliefs are shaping people’s perception of their health, cause of their health issues, and the ways through which they can overcome an illness [10]. There are many studies related to immigrants ‘health beliefs and the influence of their beliefs on their health-seeking behaviorFootnote 4; however, there are only a few that cover the impact of health beliefs on asylum seekers and refugees’ health-seeking behavior [18,19,20,21,22].

This review is designed based on the Health Belief Model (HBM) which has guided studies on health-seeking behavior; especially, health seeking behavior among minorities from different ethnic backgrounds [7, 23, 24]. Since early 1950s, HBM has been widely used as a conceptual framework in health behavior studies. The model was developed according to a well-established body of psychological and behavioral theory, focusing mainly on two variables, including the value placed by an individual on a particular goal, and an individual’s estimated possibility of achieving that goal by a given action [25, 26]. When these variables were conceptualized in the context of health seeking behavior, the correspondences were: (1) wishing to avoid illness or recover from illness; and (2) the belief that a specific health information or action will prevent illness [26].

This paper aims to perform a descriptive review to provide a holistic picture of studies related to health beliefs, and attitudes of asylum seekers and refugees and their health-seeking behavior. The research objectives guiding this study are:

-

1.

To explore asylum seekers and refugees’ health beliefs and their health-seeking behavior.

-

2.

To investigate influential factors on asylum seekers and refugees’ health-seeking behavior according to their health beliefs and cultures.

2 Research Methods

This review started with a literature search conducted in January 2022, using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27]. To be included in the review, studies had to (a) be published in English or English, along with another language, (b) focus on human health beliefs issues, (c) focus on asylum seekers, and/or refugees, and (d) be original studies, not a brief review of an original study published in a conference paper or editorial note. All kinds of quantitative and qualitative study designs were considered, including focus group discussions, structured or semi structured interviews, observations, secondary data analyses, and surveys.

The main focus of the included studies was on investigating health belief of asylum seekers and refugees rather than describing healthcare providers’ interpretations of their beliefs. The studies were excluded if their main focus was on indigenous ethnic minorities, subcultures, immigrants, or seasonal workers. Moreover, the studies were excluded when they did not provide original research findings, such as systematic reviews, literature reviews, editorial notes, or conference posters. Furthermore, all studies which investigate the research topic from different angles rather than health belief were excluded (i.e., human rights, health law, ambulatory care, safety science, mediators, health information systems, and health policy).

2.1 Research Adapted Framework

This review uses an adapted framework based on HBM to provide a comprehensive overview of literature findings related to asylum seekers and refugees’ health seeking behavior and their health beliefs and cultures. The HBM has several primary concepts that predict why individuals will take a particular action to prevent, to screen for, or to control health conditions [28].

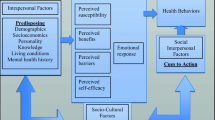

According to HBM, the three components influencing health-seeking behavior of asylum seekers and refugees include modifying factors, individual beliefs, and individual action (see Fig. 1).

-

Modifying factors are described in the original model as demographic attributes of individuals, such as age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomics, and knowledge [23]. The model proposed in this research includes modifying factors, such as gender, country of origin, county of residence, and residency ground.

-

Individual beliefs are described in the original model as perception about an illness, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and perceived self-efficacy [23]. The proposed model for this review found perceived fear that may influence or be under influence from perceived barrier.

-

Individual actions are described in the original model as individual behaviors and strategies to activate outcomes of the health seeking behavior [7, 25].

The concept in this study applied to providing a better understanding of individual beliefs and attitudes of this target group regarding their health and their health seeking behavior.

Adapted framework based on health belief model components and linkages [25]

2.2 Information Sources and Search Strategy

Reviewer searched scientific databases through Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and EBSCO for peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, books, and book chapters. Six databases (CINAHL (29 records), Medline (28 records), PubMed (35 records), PsycINFO (23 records), and PsycArticles (3 records)) were searched for the records on the association between asylum seekers, refugees and their beliefs and attitudes to health and illness.

This review started by searching for relevant studies through a medical subject heading (MeSH), truncation (*), and subject keywords adopted from Shahin et al. [28]. In addition, the terms “asylum seeker”, and “refugee” along with all their synonyms and related terms were combined with proximity operators with a distance space of 10 (adj 10) to retrieve more results. The formulated search statement of this study was as follows: “health belief* OR attitude to health OR attitude to illness OR self-care OR self-management AND refuge* OR asylum seek*”.

2.3 Data Extraction and Complete Search Strategy

A total of 120 studies were retrieved from six databases (118 records) and through backwards reference searching (2 records). Studies were selected based on the research model in three phases: reviewing titles, abstracts, keywords, and full-text records. All databases were searched simultaneously. In the review phase, the author screened all records and excluded those that did not fit into any of the categories created based on the original HBM; different strategies were used to select records with asylum seekers and/or refugees as the main subject of studies. In the second phase, abstracts of the selected studies were double-checked. Finally, full texts were screened for relevance and doubled checked for accuracy. The final selected records were imported into NVivo 1.6 for qualitative data analysis and visualization. Figure 2 presents a complete overview of the whole screening and selection process.

2.4 General Characteristic of Included Studies

The final list includes fifteen studies, covering a wide variety of themes, participants’ genders, different sample size, various methods, and varied means of data gathering. Majority of the included studies (8/15) were conducted in North America covering issues, including changing health beliefs and behaviors, cardiovascular disease, health beliefs and lifestyle, health beliefs and practices, health beliefs and women’s health, and sexual health attitudes and beliefs (See Table 1).

This review includes studied with sample size ranging from eleven to approximately three hundred individuals, adopted both qualitative and quantitative methods, and utilized different means of data gathering, such as focus group, interviews, and observations. Table 2 and Appendix 1 provide additional information, such as vulnerable group categories, ethnic groups, current residency, and country of origin of the participants.

3 Results

An adapted framework based the HBM was used to examine attitudes and cultural beliefs concerning health-seeking behavior of asylum seekers and refugees in the world. We have identified three main categories, including modifying factors, individual beliefs, and individual action (See Fig. 1). The following subsections provide findings.

3.1 Perceived Susceptibility

Table 3 provides common beliefs held across different ethnic groups within seven domains of the adapted HBM. First, common beliefs related to perceived susceptibility across all studied ethnic groups included lack of knowledge about health issues and its risk factors [13, 14, 16, 29,30,31,32], and Illnesses is caused by supernatural causes (God, Satan, or Evil spirits, magic, the evil eye) [15, 16, 29, 33,34,35,36,37]. These studies were in context of women’s health, changing health beliefs and behaviors, mental health beliefs and processes, sexual health attitudes and beliefs, HIV and Diabetes and self-management skills. Second, perceived susceptibility and unique beliefs distinct to each ethnic group were: Sudanese key informants emphasized depression is white man’s sickness [33], and Karen refugees resettled in the United States from the Thai-Myanmar (Burma) border [12] underscored lack of knowledge of the association between tobacco smoking and Cardiovascular disease.

3.2 Perceived Severity

Perceived susceptibility and perceived severity were two factors shaping perceived threat to health issues [25]. On the one hand, common health beliefs related to perceived severity included perceived susceptibility to and severity of illness or its sequelae with Bosnian, Somalian, Iraqi, Laotian, and Karen refugees in contexts of preventive health and breast cancer screening, changing health beliefs, traditional and modern health services, and cardiovascular disease respectively [12, 15, 29, 37]. On the other hand, belief about how serious a condition and its sequelae were common health beliefs among Ethiopian and Laotian in studies related to health beliefs and practices, and changing health beliefs and behaviors [15, 34]. Finally, unique beliefs distinct to African ethnic group related to perceived severity included beliefs that having HIV status would make life difficult and had considerable social problems, this was highlighted in a study with sub-Saharan asylum seekers with HIV [35].

3.3 Perceived Benefits

Perceive the action as potentially beneficial by reducing the threat was noted among perceived benefits by African, Asian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern groups [12, 15, 29]. For instance, Iraqi and Bosnian woman mentioned, “As long as the pain is for my own good in the end, I endure it,” and “Is not this for my own good? It is not for anyone else but me.” [29]. Furthermore, several women from resettled Laotian refugees reported that “they would have opted for a hospital birth because a hospital birth is safer if anything goes wrong, even had a traditional midwife been available.” [15]. One particular perceived benefits form Laotian refugees study was perceiving “western biomedicine stronger and more effective than traditional Laotian herbal remedies” [15].

3.4 Perceived Barriers

Perceived barriers were identified within four categories, including cultural and traditional factors, healthcare related barriers, health communication issues, and personal barriers.

3.4.1 Cultural and Traditional Factors

Embarrassment, fatalism, and presence of male providers were common perceived barriers in studies related to women’s health, changing health beliefs, mental health, sexual health, and cardiovascular disease by African, Asian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern groups [12, 15, 29, 31, 33, 34, 40]. Different forms of expressions related to adhered to traditional normative beliefs was common perceived barriers by African, Asian, and Middle Eastern groups [13, 14, 16, 32, 35,36,37]. For example, both Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees in studies related to their health beliefs and practices mentioned “they do not like their head or shoulder touched” and “touching from shoulder up can be anxiety and soul may leave the body and cause health problems” [16, 37].

Lack of family or community support and silence (taboo) were specified as perceived barriers in studies on health beliefs and practices among Burundian, Eritrean, Ethiopian, and Somalian refugees [30, 34, 40]. As an example, silence was highlighted as a major barrier to effective implementation of adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights program by Rwandan government [40]. A preference for a physician from the same cultural background was a perceived barrier mentioned in a study on cardiovascular disease–related health beliefs and lifestyle issues among Karen refugees [12].

3.4.2 Healthcare Related Barriers

Abrupt or hostile behavior of health care personnel, administrative barriers to care, and distrust of the healthcare system were mentioned as perceived barriers among Cambodian and Laotian refugees [16, 37]. Cambodian refugees mentioned issues related to language and cultural barriers, crowded waiting rooms, multiple interviews, and mysterious procedures as their perceived barriers to healthcare [16].

3.4.3 Health Communication Issues

Poor patient and healthcare provider communication skills were common perceived barriers in studies related to women health, changing health beliefs and practices by African, Asian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern groups [15, 29, 34, 36, 37]. Difficulty in finding interpreters was described as “limited availability of language interpreters and scheduled basis” as another perceived barrier related to health communication among Laotian refugees [37].

3.4.4 Personal Barriers

Inattentiveness to personal health and psychological barriers were commonly mentioned personal perceived barriers by African, Asian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern groups [12, 16, 29, 33]. For example, approximately two-thirds of women in a comparative qualitative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening across Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somalian populations identified psychosocial barriers as barriers to uptake of preventive breast cancer screening [29]. Perceptions of racism was highlighted as Ethiopian refugees’ individual perceived barriers [34].

3.5 Perceived Fear

Fear awareness of their community about preventive health issues, and fear of pain or diagnosis with breast cancer were two common perceived fears in a study with Bosnian, Iraqi and Middle Eastern female women on preventive health and breast cancer screening [29]. Fear one’s partner or family judgment was a common predictor of behavioral changes among sub-Saharan African and Afghan refugees in studies on asylum seekers with HIV, Afghan refugees and reproductive health attitudes [14, 35].

In terms of unique fear across African groups, different aspect of cultural, religious, community issues were mentioned by Burundian, Eastern African, Sundaneses, sub-Saharan African refugees in studies on mental health, sexual health, HIV and health beliefs, pregnancy and perinatal care, and health beliefs and practices (See Table 4) [13, 30, 33, 35, 40]. Cambodians’ female refugees mentioned two perceiving or recognizing barriers to care as fear of having blood drawn during medical examination, and fear that IUDs will destroy the uterus [16].

3.6 Perceived Self-efficacy

Confidence in one’s ability to complete steps needed to face health issue, and intentions to keep doctor’s appointments were the common expectations of self-efficacy among Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somali women in a study on refugee preventive health and Breast Cancer Screening [29].

Furthermore, positive elements of self-efficacy were identified among studies with African individuals, including ability to recognize the threat to their health, confidence in one’s knowledge and ability to explain the health results to others, and adopting health-promoting behaviors through exercise or relaxation techniques to reduce stress in contexts of health practice and health beliefs, mental health, and HIV and self-management skills [30, 33,34,35]. Laotian refugees showed capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage their health through intentions to follow diet for their health benefit [37].

3.7 Cues to Action

Commonly cited cues to action across African, Asian, Balkan, Middle Eastern populations included physician’s recommendation [29, 37], flexibility in scheduling [29], group educational program [32, 35], help from physicians and other healthcare providers [29], and support from family and friends [30, 32, 34, 37] (see Table 4). There were also particular cues to action among different ethnic groups represented in this review. Consulting with traditional healing specialists, and consulting with local pharmacists were unique cues to action among Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese refugees in different studies [15, 16, 36, 37]. Afghan and Syrian refugees mentioned access to gynecological information, and community health worker in studies on women’s health and diabetes as their cues to action [14, 32]. Finally, support from community was an important motivator to seeking care by Somalian, Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Sudanese [30, 33].

4 Discussion and Conclusion

This review shed light on cultural beliefs and attitudes shaping asylum seekers and refugees’ health beliefs, and their health-seeking behavior. The culture, tradition, fate or destiny, psychological factors, family, friends, and community were mentioned as the crucial influential factors in shaping how asylum seekers, and refugees perceived barriers, fear, severity, and susceptibility in their health seeking activities by African, Asian, Balkan, and Middle Eastern groups [13,14,15,16, 29, 32, 33, 36, 37].

More specifically, different forms of supernatural causes, fatalism, traditions and issues related to communications with healthcare providers were the common influential factors in health seeking activities by Asian and Middle Eastern asylum seekers and refugees [12, 14,15,16, 29, 32, 36, 37]. However, cultural shame, racism, and community were mentioned as most influential factors in African refugees and asylum seekers health seeking behavior [30, 34, 40]. The increasing number of refugees and asylum seekers in the world leads to call upon healthcare providers and public health community to devise culturally relevant strategies that will effectively target different asylum seekers and refugees’ groups with diverse cultural, traditional beliefs and attitudes about healthcare and health seeking activities.

Knowledge and awareness related to benefits of using modern healthcare services was highlighted as motivator for different ethnic groups to take care of their personal health [12, 15, 29]. More specifically, when the asylum seekers or refugees had enough information related to individual health, expectations of self-efficacy were found through different forms, including increasing confidence, intention, recognition, and adopting healthy lifestyle among refugees and asylum seekers [29, 30, 33, 34].

Adopting strategies, including providing health educational programs aiming at increasing asylum seekers and refugees’ health literacy, knowledge, and awareness about health benefits of using modern healthcare services were highly recommended to the medical and public health community who are dealing with individuals with diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Physicians and healthcare providers, educational programs, and support from family, friends, and community had noteworthy influence on triggering the health-related decision-making process among asylum seekers and refugees [14, 16, 29, 30, 32,33,34, 36, 37]. This review shows the importance of engaging family and community support networks in health educational programs to eliminate or reduce the social stigma and cultural shame in using healthcare services as well as to bridge an understanding of cultural notions of health and disease among different ethnic groups of asylum seekers and refugees within the framework of modern healthcare structure.

This study proposed an adapted framework based on HBM and explored extensively health-seeking behavior of asylum seekers and refugees from cultural, psychological, religious, and traditional perspectives. However, there are limitations in applying adapted frameworks in terms of influential contextual factors in health seeking activities of the vulnerable groups, such as healthcare system and structure of different countries, which may have key role in shaping health beliefs and practices of these people but are not reflected in the model. Moreover, different studies related to the investigation of health beliefs of the vulnerable population have applied different methods (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) in different contexts (i.e., women’s health, mental health, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes) to examining health-seeking behavior that imposes significant limitations in the generalization of the findings.

The model proposed in this paper has different components influencing health-seeking behavior of asylum seekers and refugees in relation to modifying factors, individual beliefs, and individual action. However, included studies in the review did not consistently reflect information related to their studied groups in terms of age, gender, knowledge, and socioeconomic factors. Nonetheless, exploring health beliefs of vulnerable groups through adapted HBM provides significant information and understanding on cultural beliefs and attitudes that shape asylum seekers and refugees’ health-seeking behavior. The outcome of applying such model is expected to provide practical guidelines for developing culturally appropriate health interventional programs to enhance compliance.

There were a few limitations in conducting this descriptive review. One of the primary limitations was the number of studies investigating health beliefs and behavior of asylum seekers and refugees. There was also inconsistency in providing information about studies of vulnerable group and their attitudes and behavior from the components of HBM perspectives. In addition, we also acknowledge that this review may not represent all relevant fields, as the scientific databases used in this review did not necessarily contain references to all the key publications. However, we are confident that the studies examined and evaluated in the review provide an overall overview of the body of academic publications within this multidisciplinary area of research.

5 Future Research Recommendation

The first recommendation for future studies calls upon healthcare providers, immigration authorities, policy makers, researchers, and surveyors to gather more comprehensive details on demographic, socio-cultural and migration-related information of refugees and asylum seekers. This information will facilitate recognizing asylum seekers and refugees’ health beliefs, and their impact on their health-seeking behavior. Another recommendation is to conduct more studies related to asylum seekers and refugees’ health beliefs to gain a better understanding of their needs for health services and health-related information and to develop health educational programs for their caregivers so that they are better able to meet these needs. The last recommendation is to shift away from solely investigating health service provision to adopting a cross-cultural and religious approach to provision of health services and health-related information for these people to meet the highest rate of satisfaction among these healthcare consumers.

Notes

- 1.

A refugee is an individual who have fled war, violence, conflict, or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country [1].

- 2.

An asylum-seeker is an individual who has left their country and is seeking protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another country; However, an asylum-seeker hasn’t yet been legally recognized as a refugee and is waiting to receive a decision on their asylum claim [2].

- 3.

Health beliefs are what individuals believe about their health, what they think constitutes their health, what they consider the cause of their illness, and ways to overcome an illness it [10].

- 4.

Health seeking behavior is any activity undertaken by people who perceived themselves to have a health issue or to be sick aiming at finding an appropriate treatment [17].

- 5.

Perceived susceptibility “refers to beliefs about the likelihood of getting a disease or condition” [25].

- 6.

Perceived severity is “individual’s beliefs related to the effects of a given health issue and the difficulties related to the health condition, such as pain, loss of work time, financial issues, and issues related to personal and family relationships” [38].

- 7.

Perceived benefits refers to “beliefs about the positive outcomes associated with a behavior in response to a real or perceived threat” [39].

- 8.

Perceived barriers are “the potential negative aspects of a particular health action and may act as impediments to undertaking recommended behaviors” [25].

- 9.

Perceived fear refers to an important predictor of behavioral changes and health-securing behaviors in response to perceiving or recognizing barriers to care [41].

- 10.

Perceived self-efficacy refers to “beliefs in individual’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations” [42].

- 11.

Cues to action refers to “stimulus needed to trigger the decision-making process to accept a recommended health action” [43].

References

U.N.H.C.: What is a refugee. https://www.unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html. Accessed 06 Mar 2022

Amnesty International Refugees: Asylum-seekers and Migrants. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/refugees-asylum-seekers-and-migrants/. Accessed 06 Mar 2022

Alaoui, A., Patel, N., Subbiah, N., Choi, I., Scott, J., Tohme, W., Mun, S. K.: Health Information Sharing System for Refugees and Immigrants in Five States, In: 1st Transdisciplinary Conference on Distributed Diagnosis and Home Healthcare, D2H2., pp. 116–119. IEEE, Arlington, VA, USA (2006)

Benisovich, S.V., King, A.C.: Meaning and knowledge of health among older adult immigrants from Russia: a phenomenological study. Health Educ. Res. 18(2), 135–144 (2003)

Katila, S., Wahlbeck, Ö.: The role of (transnational) social capital in the start-up processes of immigrant businesses: the case of Chinese and Turkish restaurant businesses in Finland. Int. Small Bus. J. 30(3), 294–309 (2012)

Degni, F., Suominen, S., Essén, B., Ansari, W.E., Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.: Communication and cultural issues in providing reproductive health care to immigrant women: health care providers’ experiences in meeting the needs of [corrected] Somali women living in Finland. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 14(2), 330–343 (2012)

Joseph, R., Fernandes, S., Derstine, S., McSpadden, M.: Complementary medicine & spirituality: health-seeking behaviors of Indian immigrants in the United States. J. Christ. Nurs. 36(3), 190–195 (2019)

Pangas, J., et al.: Refugee women’s experiences negotiating motherhood and maternity care in a new country: a meta-ethnographic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 90, 31–45 (2019)

Mangrio, E., Carlson, E., Zdravkovic, S.: Newly arrived refugee parents in Sweden and their experience of the resettlement process: a qualitative study. Scand. J. Public Health 48(7), 699–706 (2020)

Misra, R., Kaster, E.C.: Health beliefs. In: Loue, S., Sajatovic, M. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Immigrant Health, pp. 766–768. Springer, New York (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5659-0_332

Williams, N.E., Thornton, A., Young-DeMarco, L.C.: Migrant values and beliefs: how are they different and how do they change. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud. 40(5), 796–813 (2014)

Kamimura, A., Sin, K., Pye, M., Meng, H.W.: Cardiovascular disease-related health beliefs and lifestyle issues among Karen refugees resettled in the United States from the Thai-Myanmar (Burma) border. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 50(6), 386–392 (2017)

Dean, J., Mitchell, M., Stewart, D., Debattista, J.: Intergenerational variation in sexual health attitudes and beliefs among Sudanese refugee communities in Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 19(1), 17–31 (2017)

Piran, P.: Effects of social interaction between Afghan refugees and Iranians on reproductive health attitudes. Disasters 28(3), 283–293 (2004)

Brainard, J., Zaharlick, A.: Changing health beliefs and behaviors of resettled Laotian refugees: ethnic variation in adaptation. Soc. Sci. Med. 29(7), 845–852 (1989)

Kemp, C.: Cambodian refugee health care beliefs and practices. J. Commun. Health Nurs. 2(1), 41–52 (1985)

Ward, H., Mertens, T.E., Thomas, C.: Health seeking behaviour and the control of sexually transmitted disease. Health Policy Plan. 12(1), 19–28 (1997)

Alvarez-Nieto, C., Pastor-Moreno, G., Grande-Gascón, M.L., Linares-Abad, M.: Sexual and reproductive health beliefs and practices of female immigrants in Spain: a qualitative study. Reprod. Health 12(1), 1–10 (2015)

Jenkins, C.N.H., Le, T., McPhee, S.J., Stewart, S., Ha, N.T.: Health care access and preventive care among Vietnamese immigrants: do traditional beliefs and practices pose barriers. Soc. Sci. Med. 43(7), 1049–1056 (1996)

Cooper Brathwaite, A., Lemonde, M.: Health beliefs and practices of African immigrants in Canada. Clin. Nurs. Res. 25(6), 626–645 (2016)

Smith, A., et al.: The influence of culture on the oral health-related beliefs and behaviours of elderly Chinese immigrants: a meta-synthesis of the literature. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 28(1), 27–47 (2013)

Shah, S.M., Ayash, C., Pharaon, N.A., Gany, F.M.: Arab American immigrants in New York: health care and cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 10(5), 429–436 (2008)

Becker, M.H.: The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 2(4), 409–419 (1974)

Aalto, A.M., Uutela, A.: Glycemic control, self-care behaviors, and psychosocial factors among insulin treated diabetics: a test of an extended health belief model. Int. J. Behav. Med. 4(3), 191–214 (1997)

Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K. (eds.): Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco (2008)

Janz, N.K., Becker, M.H.: The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ. Q. 11(1), 1–47 (1984)

Shamseer, L., et al.: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350, 1–25 (2015)

Mckellar, K., Sillence, E.: Current research on sexual health and teenagers, Chap. 2. In: Mckellar, K., Sillence, E. (eds.) Teenagers, Sexual Health Information and the Digital Age, pp. 5–23. Academic Press (2020)

Saadi, A., Bond, B.E., Percac-Lima, S.: Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somali refugee women speak: a comparative qualitative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening. Womens Health Issues 25(5), 501–508 (2015)

Simmelink, J., Lightfoot, E., Dube, A., Blevins, J., Lum, T.: Understanding the health beliefs and practices of East African refugees. Am. J. Health Behav. 37(2), 155–161 (2013)

Dhar, C.P., et al.: Attitudes and beliefs pertaining to sexual and reproductive health among unmarried, female Bhutanese refugee youth in Philadelphia. J. Adolesc. Health 61(6), 791–794 (2017)

Elliott, J.A., et al.: A cross-sectional assessment of diabetes self-management, education and support needs of Syrian refugee patients living with diabetes in Bekaa Valley Lebanon. Confl. Health 12(1), 40–50 (2018)

Savic, M., Chur-Hansen, A., Mahmood, M.A., Moore, V.M.: “We don’t have to go and see a special person to solve this problem”: trauma, mental health beliefs and processes for addressing “mental health issues” among Sudanese refugees in Australia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 62(1), 76–83 (2016)

Papadopoulos, R., Lay, M., Lees, S., Gebrehiwot, A.: The impact of migration on health beliefs and behaviours: the case of Ethiopian refugees in the UK. Contemp. Nurse 15(3), 210–221 (2003)

Kennedy, A.P., Rogers, A.E.: The needs of others: the norms of self-management skills training and the differing priorities of asylum seekers with HIV. Health Sociol. Rev. 18(2), 145–158 (2009)

Rocereto, L.: Selected health beliefs of Vietnamese refugees. J. School Health 51(1), 63–64 (1981)

Gilman, S.C., Justice, J., Saepharn, K., Charles, G.: Use of traditional and modern health services by Laotian refugees. West. J. Med. 157(3), 310–315 (1992)

Johnson, C.E., Mues, K.E., Mayne, S.L., Kiblawi, A.N.: Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review using the health belief model. J. Lower Genital Tract Dis. 12(3), 232–241 (2008)

NCI Perceived Benefits—Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS). https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/constructs/perceived-benefits. Accessed 07 Mar 2022

Ruzibiza, Y.: Silence as self-care: pregnant adolescents and adolescent mothers concealing paternity in Mahama refugee camp. Rwanda. Sex. Cult. 26, 994–1011 (2021)

Eder, S.J., et al.: Predicting fear and perceived health during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning: a cross-national longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 16(3), e0247997 (2021)

Watts, R.E.: Self-efficacy in changing societies. J. Cogn. Psychother. 10(4), 313–315 (1996)

LaMorte, W.: The Health Belief Model. https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/behavioralchangetheories2.html. Accessed 07 Mar 2022

Acknowledgement

This paper and the research behind it would not have been possible without the exceptional support of my supervisors, Dr Kristina Eriksson-Backa & Dr Shahrokh Nikou; and this research was supported by the grant from Finnish Cultural Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Ethnic group and sub-ethnic groups of included studies in the review.

Ethnic group | Sub-ethnic group |

|---|---|

African | Burundian, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Somalin, sub-Saharan African, Sudanese |

Asian | Bhutanese, Cambodian, Laotian, Myanmarese, Vietnamese |

Balkan | Bosnian |

Middle Eastern | Afghan, Iraqi, Syrian |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Ahmadinia, H. (2022). A Review of Health Beliefs and Their Influence on Asylum Seekers and Refugees’ Health-Seeking Behavior. In: Li, H., Ghorbanian Zolbin, M., Krimmer, R., Kärkkäinen, J., Li, C., Suomi, R. (eds) Well-Being in the Information Society: When the Mind Breaks. WIS 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1626. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14832-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14832-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14831-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14832-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)