Abstract

School systems and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have long acknowledged the levels of social, cultural and epistemic disaffection and contestation that have historically existed between teachers and schools, and Indigenous students, families and their local communities. This relationship is both part symptomatic and part causal of the broader and highly complex array of legal and socio-economic issues that underpin the often highly fraught relationships existing between these communities and schools. The findings of this review provide insights into the everyday environments of these interactions, the possibilities that emanate from their establishment and the hope that these interactions can positively impact on students’ educational outcomes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

An analysis of both the last ten years of the state and commonwealth ‘Closing the Gap’ strategy, and the ever-growing corpus of educational on the schooling of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander student, highlights the pervasiveness of student underachievement, systematic community and school conflict and resistance, and cultural contestation between schools and Indigenous people (Guenther et al., 2019). The admission of schools’ failure to shift the current levels of student underachievement over the last 25 years since the inception of the first Aboriginal Education Policy (Department of Education and Training, 1989) saw the Rudd Government, with the states and territories establish the Closing the Gap strategy. This whole-of-community and government strategy gave particular prominence to education, with three of the seven national strategies focusing on at least halving if not closing the gap for Indigenous student’s literacy and numeracy outcomes, and their retention to Year 12.

In their attempts to achieve these targets, Governments have often pursued policies and/or strategies that have demonstrated little evidence of significant educational outcomes for Indigenous students. These have included policies that have endorsed unproven strategies like boarding school strategies for students in remote locations (NT, WA and Qld), Attendance Strategies (NSW, NT, SA, WA and Qld); targeted pedagogical programs (Direct Instruction or Accelerated Literacy); and national curriculum initiatives to include the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cross-Curriculum Priorities. Sitting beside these, are the welter of systemic programs, including policies that attempted to mandate schools to ‘partner’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. This 20 year plus perennial project (e.g. NSW AECG & NSW DET, 1999) has been instituted by school systems to draw Indigenous families into the task of ‘supporting’ schools to improve their children’s educational outcomes (Smith et al., 2017).

While government policies, such as the NSW DET Connected Communities Strategy (2012), have elevated the importance of Aboriginal communities’ engagement to ‘sharing the endeavour’ in educating Aboriginal children (NSW AECG & NSW DET, 2010). The 2013 NSW Ochre Strategy, in noting the dimension of all governments’ policy dilemma said that their preliminary consultation highlighted:

[T]he concerns raised by Aboriginal communities over the absence of genuinely shared decision-making, the duplication of services, lack of coordination, unclear accountability pathways and—despite significant investment over time—limited demonstrable improvement in the lives of Aboriginal people in NSW. NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs (2013, p. 7)

Though NSW specific, these findings ring true across other jurisdictions, with Fogarty et al. (2018) and Patrick and Moodie (2016) identifying concerns about government policy, their inability to deliver the promise of equitable outcomes and failure to bolster wider reconciliatory discourses to guide long-term socio-cultural reform of government in support of Indigenous Australians.

Unsurprisingly, research by Munns et al. (2013) argues that the social, cultural and epistemic disconnect between schools and Aboriginal people rests in part on teachers’ inability to see how their deficit based ‘professional’ beliefs influence their ability to understand the educational needs of Aboriginal students. Conversely, other research attests to parents’ often heard contention, that ‘good’ teachers underpin their teaching through inclusive curriculum, relational pedagogies strategies that reach out to families, and seeking opportunities to learn of and from their students and community’s cultures and histories (Guenther et al., 2015; Perso et al., 2012; Vass, 2017). These two positions frame the field of contestation that surrounds the work that community and school engagement could possibly do in support of the education of Indigenous students.

The complexity of the history of dissonance between Indigenous families and schools has been shown to affect the educational achievements of Aboriginal students (Sanderson & Allard, 2001) and begs for school action to find the means to link themselves to the families of these children. Yet the history of these efforts (of which there have been many) has been largely based on an unquestioned policy assertion that these interactions are in themselves, a curative for student underachievement and a self-actualizing instrument of change in schooling practices (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014; NSW AECG & NSW DET, 2010).

Though mindful of this long history of engagement policy failure, this review is positioned from within an awareness that Indigenous families continue their insistence on establishing multiple opportunities for meaningful engagement with schools. This, they argue, must inform new ways of schooling that would resonate with their social, cultural and educational aspiration of ‘Success as Aboriginal’, where a student’s self-assertion of their Indigenous identity is itself a wellspring for educational success. As such, this review appraises the body of recent Australian research, on the establishment and implementation of the collaborative efforts of schools and Indigenous communities, identifying evidence of their impact and highlighting the identified preconditions which underpin its success or failure. Based on our commitment to the Critical Indigenous methodology, the researchers asked: What issues affect the development of Aboriginal community and school collaboration and what impact have these had on schools and Aboriginal students, families and their communities?

Method

The systematic review is an increasingly used methodology applied to locate and analyze the body of research that can assist in answering specific research questions. It sets out the development of a methodical process through which the research literature can be carefully sifted to locate research that meets specific requirements identified in the research question (Gough et al., 2012). The aim of this review is to test the evidence for often-made assertions that school and Indigenous community engagement supports students’ schooling outcomes through the initiation of productive and authentic relationships between families and their children’s schools.

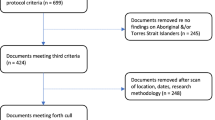

The review is an iterative investigation using search terms drawn directly from the inquiry question and project protocols as set by the PICo frameworkFootnote 1 (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). These focused this investigation on the population of Australian Indigenous students, their families and communities, three phenomena of interest—engagement/s between schools and Indigenous people, their impact on participants, and the effect of school-based cultural programs on students and community engagement. These criteria were investigated within the context of K–12 schools. In addition to these criteria, the studies were appraised against the additional project protocol of time (2005–2017) and a ‘quality’ criterion used to evaluate researchFootnote 2 (Coughlan et al., 2007). This initially search identified 1050 studies that meet the PICo requirements which were whittled down using the six inclusion/exclusion phases until there were 32 studies that met all review requirements identified in Fig. 5.1.

PRISMA flow diagram representing inclusion and exclusion process. Adapted from Fig. 1, in ‘Factors affecting the development of school and Indigenous community engagement: A systematic review’, by K. Lowe, N. Harrison, C. Tennent, J. Guenther, G. Vass & N. Moodie, 2019, Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), p. 257

Findings

This systematic review question is in two parts—initially identifying both the barriers and enabling elements shown to affect Aboriginal families/communities and school’s engagement, and the evidence of their impact on any of the stakeholder groups.

Barriers to Engagement

Unsurprisingly, many of the 32 studies identified personal, structural or epistemic barriers seen to negatively impact on community and school collaboration. This discursive body evidence centered on three interlocking concerns, the impact of a long history of colonial dispossession, the effect of schools’ low expectations on teachers, Indigenous families and students, and the negative practices of schooling which were seen to affect relational disengagement.

Colonial Experiences

Bond’s (2010) study of the role of Elders in the education of Aboriginal students on Mornington Island highlighted the effect of systemic policies seen to support the breakdown of social cohesion, the acceleration of the loss of local cultural practices and school’s deliberative exercising of its ‘authority’ in ways that marginalized the Elders’ authority within their communities.

The legacy of schools and their role in perpetuating Indigenous disadvantage was seen in the studies by Hayes et al. (2009) and Woodrow et al. (2016), who reported that Aboriginal families identified the sorry legacy of schooling and its impact on community socio-cultural dislocation. These studies identified that even when schools looked to reach out to the community, they failed to comprehend the perception that schools had actively participated in subjugating local community languages, cultural knowledge and student identities.

The impact of this history was evidenced by Muller and Saulwick (2006) and Hayes et al. (2009), who noted that while on the one hand Aboriginal parents expressed the desire to establish a relationship with teachers, they also spoke of their underlying mistrust of school motivation in proposing such a policy. This finding was supported by Chenhall et al. (2011), Barr and Saltmarsh (2014) and Woodrow et al. (2016), who found that Indigenous families identified that many school programs sat within deficit discourses about them and their children, an unwillingness among many teachers’ to shift their pedagogic practices, and rampant tokenism in the ways that Indigenous knowledge was represented in classrooms. Mechielsen et al. (2014) found schools and communities appeared to be locked into contested practices where school inclusion strategies were seen by communities as furthering the schooling project of assimilation and cultural displacement.

Low Expectations

Yunkaporta and McGinty (2009) found that while Aboriginal students were often victims of low expectations, and where in some cases these actually emanated from within Aboriginal communities themselves. They found that one of the consequences of tribal dispersal was the levels of internal resistance by some within the local Indigenous community who vigorously questioned the value of revitalizing the local language and cultural knowledge. This ginger group claims that this knowledge negatively impacted Indigenous students’ learning through their exposure to ‘primitive’ knowledge, a claim emanating from the long history of ‘cognitive imperialism’ that spawned Indigenous self-loathing while furthering the endeavor of their cultural assimilation (Battiste, 2004).

Studies by Hayes et al. (2009), Muller (2012) and Woodrow et al. (2016) identified how the historic effect of racism crossed generations, impacting on community expectations and students’ self-efficacy, the high levels of student self-sabotage and social ‘shame’, and the heightening of students’ resistance to both school and schooling.

In line with this, several studies suggested that the impact of heightened levels of socio-economic disadvantage among Aboriginal families shaped the nature of their relationship with government. Chenhall et al. (2011), Chodkiewicz et al. (2008) found that schools argued that their capacity to engage Aboriginal families was limited by the community’s low SES, which then impacted on their ability to access social services. These findings highlighted the powerful negative discourses that perversely suggested schools should be exonerated of perpetuating Indigenous student underachievement. This theme appeared to be taken up in the study by Chenhall et al. (2011), who suggested that ‘some’ parents were in part to blame for the high level of student truancy, which it was argued, was as a consequence of pervasive disadvantage that affected the schools’ capacity to address the learning needs of Aboriginal students. Muller’s (2012) study advanced a number of significant findings on the impact of ‘shame’ in Indigenous communities. He argued that this wellspring of Aboriginal fear and social humiliation, paralyzing parent’s ability to take an active role in their children’s education, and instead becoming a source of resistance to the perceived infractions by teachers and the school.

Schooling Practices

Several studies highlighted the issue of community access (or lack of) to the school had a negative impact on parents’ engagement with schools. Barr and Saltmarsh (2014) highlighted the complexity of the history-laden discord between schools and Indigenous communities, especially the latter’s perceptions on how schools exercised their considerable power over both students and families. While Berthelsen and Walker (2008) noted the level of teacher resistance to engaging with parents and the consequent impact that this had in sapping parents’ willingness to engage with them, Muller (2012) suggested that when teachers were seen to support this engagement, it was seen to counter the cycle of dissonance and resistance between them and parents.

Several studies reported on engagement programs that sought to enhance student outcomes through ‘improving’ their school attendance. The research highlighted that these programs primarily pivoted on two key discourses—the first which focused on community capacity building to ‘improve’ parental support for the school (Lea et al., 2011), and a second that sought to responsibilize ‘good’ families to influence community opinion in support of the school (Chodkiewicz et al., 2008; Woodrow et al., 2016).

This research highlighted the mismatch in the purpose of these collaborations, with parents arguing that they sought to influence and inform the school and its teachers about their communities, while schools sought to engage parents to the primary task of supporting their efforts to educate their children (Lowe, 2011). Lewthwaite et al. (2015) have suggested that Indigenous families that felt isolated from schools were often exasperated by teacher ‘ignorance’ or worse, resistant to engaging with local Indigenous knowledge and experiences. Overall, these studies underscore well-known community concerns that school programs developed to support community engagement were vague, generalized, ‘feel good’ policies that, though speaking of inclusion, actually provided little authentic access to inform the school and/or teachers practices (Cleveland, 2008).

Enablers

This second theme identified those findings that recorded the policies, practices and actions of schools and communities themselves that enabled positive and effective community and school collaborations.

Beliefs

Four studies made references to the impact of positive engagement on informing teachers’ beliefs and attitudes, their understanding of Indigenous knowledges, and insights into the lived of families. Woodrow et al.’s (2016) study identified that parents saw that access to Indigenous knowledge was critical for their children’s sense of identity, believing that it would fortify them against assimilatory practices of schools. Harrison and Murray (2012), Woodrow et al. (2016) and Ewings’ (2012) studies identified how the establishment of quality micro-collaborations between teacher/s and Aboriginal Education workers and Elders had a significant impact in that it improved teachers’ classroom practices, saw families invited into classrooms and evidenced curriculum and pedagogic collaboration that legitimated local epistemologies and provided the moment when students could sense these communities connection to Country.

Engagement

Several studies looked to identify effective collaboration between Aboriginal people and schools, where families could exercise their social and cultural capital in support of their children’s education. Chenhall et al. (2011), Chodkiewicz et al. (2008) and Lowe (2017) found that increased social interactions underpinned emerging levels of trust and respect between the school and families as they worked together to support establishing impactful school programs. Studies by Lowe (2017), Lea et al. (2011), Lovett et al. (2014) and Bond (2010) identified how the communities were enabled through their engagement, to garner wider institutional support in establishing what they saw as ‘high value’ cultural programs, the inclusion of local knowledge in the schools’ curriculum and the consequential positive impact of enhancing the position of Elders.

It appeared from the studies that when programs were co-developed, possibly taught and then evaluated, there was significantly higher levels of trust, respect, especially when these programs were seen to support the pedagogical presence of local Aboriginal cultural and language programs. Guenther et al. (2015), Kamara (2009), Lowe (2017) and Woodrow et al. (2016) found that the establishment of these programs in particular significantly strengthened the quality of the community’s relationship with the school. Guenther et al. (2015), Ewing (2012), Muller’s (2012) and Woodrow et al. (2016) evidenced that the teaching of local languages provided a framework for deep epistemic and pedagogical exchange between teachers, students and their communities. This discussion identified how the establishment of genuine educational programs facilitated a shift in schools’ conceptualization of social justice, authentic engagement and relationship building. This is the critical underpinning and often untapped facility of trust that is needed to secure effective school and local Aboriginal community engagements (Auerbach, 2012).

Leadership

The issue of co-leadership loomed large, highlighting the deliberative action of Indigenous agency in purposefully seeking out school leaders as they sought to affect purposeful collaborations. Bennet and Moriarty (2015) highlighted initiatives of Elders and Aboriginal education officers (AEOs) in support of the opportunity to work with pre-service teachers to develop the necessary skills to establish partnerships with parents. Owens’ (2015) study also focused in on community agency and leadership, with the community pressing the school to support efforts to establish a school-based childcare program. Further, Bond’s (2010) study highlighted how community Elders ‘guided’ her research to investigate how successive school administrations had marginalized their social and cultural influence on the school and its staff. Lowe’s (2017) study also zeroed in on the exercise of community agency when Indigenous communities were seen to challenge through very purposeful resistance, to the school’s financial practices in expending Indigenous grant money. While these studies provide examples of community leadership, studies by Kamara’s (2009), Barr and Saltmarsh (2014), Hayes et al. (2009) and Curriculum Services (2012) all identify how principals’ effectiveness needs to be measured against their ability to build a culture of transformative change. Lovett et al. (2014) found that these leaders exhibited an acute understanding of the history of Aboriginal education and the impact of those discourses that normalized the exercise of power over Aboriginal people.

Mobilizing Capital

This category captured details that identified the deliberate actions of community and teacher in seeking opportunities for purposeful collaboration. Berthelsen and Walker (2008) noted the impact when Aboriginal parents were able to clearly articulate the educational aspirations for their children. This was similar to that which motivated the Elders in Bond’s (2010) study as they set out to expose the litany of school actions that had over the previous 30 years, reduced their influence on how schooling was conducted on their island. Lampert et al. (2014) identified how the community had encouraged and facilitated teacher’s involvement in programs that deepened their understanding of their connection to Country. Other studies also identified the positive effect that the presence of Aboriginal staff had on the school and students, with Dockett et al. (2006) and Lowe (2017) evidencing how this legitimated local knowledge and Indigenous pedagogies when Aboriginal teachers were given the opportunity to teach in classrooms.

Each of these studies identified how these collaborations became foundational to the direction that schools took as they progressively developed a keener understanding of the importance of establishing programs that supported the exercise of their social capital to influence school practices, and in turn build deeper relational trust, respect and reciprocity between teachers and the Aboriginal community.

Impact of Collaboration

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities

One of the disconcerting elements of this review was the non-existence of evidence that school and community engagement programs could identify a causal effect on the educational outcomes of students. Barr and Saltmarsh (2014), Chenhall et al. (2011) and Cleveland (2008) each identified that one of the reasons for communities’ reticence in engaging with schools was informed by the belief that schools were largely disinterested in ‘real’ collaboration as their position was infected with deficit views of the Indigenous students in their care. However, this position is somewhat mitigated by the studies of Bennet and Moriarty (2015) and Guenther (2011) who found evidence of the positive outcomes that accrued to student well-being when Aboriginal communities engaged with schools. They further noted that the impact of community engagement was amplified when communities felt that their ‘ownership’ over the programs provided greater leverage in determining the direction of their children’s education. In all, these studies underscored the contention of many Indigenous people that the success of any program was reliant on finding the tipping point where parental trust in the school, its programs’ authenticity and purposefulness were oriented to addressing students’ educational and ontological needs.

Teachers/School

The second area of impact focused on how high-quality engagement projects with Aboriginal parents and schools were almost singularly dependent on the transformational leadership skills of principals, teachers (Barr & Saltmarsh, 2014; Lowe, 2017) and/or Indigenous families (Lowe, 2017). These leaders were shown to construct valued moments of engagement, engendering high levels of relational cache that enabled them to manage the instances of resistance that always reared its head. As Bennet and Moriarty (2015) and Bond (2010) noted, the importance of building relational bridges between teachers and students was that they underpinned multiple and innovative engagements that developed out of these newfound relationships. Lampert et al. (2014) found that it was Aboriginal community who wanted to broker a relationship that facilitated working with teachers so that they could understand the socio-cultural complexities of their lives and aspirations. While parents expressed a desire to be more actively involved in their children’s schooling, they also identified that principals and teachers had the ultimate responsibility to improve their children’s outcomes.

Discussion

Purpose of Engagement

While the purpose of school and community engagement was explicitly discussed in at least half of the studies, there were a variety of different articulations as to what such a purpose should be, with Bennet and Moriarty (2015), Bond (2010) and Maxwell (2012), suggesting that the purpose of community engagement was to assist teachers’ understanding of the experiences and aspirations of Aboriginal communities, their local epistemologies and their connectedness to Country. Studies like those by Lowe (2017) and Owens (2015) highlighted the actions of Aboriginal communities as they enacted their broader agendas through establishing collaborations with schools. It was seen that these communities looked to ally schools to their broader social, cultural and political aspirations to establish culturally ‘valued’ programs that went beyond the classroom and garnered wider recognition and support for reconciliation, recognition and sovereignty.

Critical Challenges

Overall, the review facilitated the identification of findings that related to the establishment of successful programs between schools and a small number of Australian Indigenous communities. In respect of Indigenous families, the findings suggested that they looked for authentic opportunities for collaborations that had the purpose of transforming their children’s educational opportunities. Parents wanted their participation to have a purpose, of impacting teachers’ beliefs, knowledge and understanding and opening eyes to their aspirations for their children (Barr & Saltmarsh, 2014).

The review highlighted findings that spoke of the critical role of schools and teachers in being enabled to develop relational strategies and to build trust and respect (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014; Barr & Saltmarsh, 2014; Bennet & Moriarty, 2015). Secondly, studies by Bond (2010) and Guenther et al. (2015) identified that quality relationships were based on relational factors, such as teacher compassion, and programs that empowered Indigenous communities to have higher expectation of themselves and schools. Notwithstanding their understanding of the challenges, Indigenous families have argued that teachers need to be supported to see their responsibility in actively affecting the policy and pedagogical changes needed to challenge the status quo that has legitimated Indigenous underachievement.

Conclusion

This systematic review of recent situated Australian research on school community engagement has explored the question of the impact that Aboriginal community and school collaboration has on schools and Aboriginal students, families and their communities. What emerged from these studies is that the issues shown to inform the Indigenous schooling success or failure need to be seen as complex and bounded by the uniqueness of each context, including the histories of each location and the quality and authenticity of engagement between each school and their local communities. Further, issues of school and community leadership were also seen to affect their individual and collective capacity to establish collaborations, especially when issues of power over the making of key educational decisions were at stake. Families and community leaders looked to be genuinely engaged in the making of decisions that impact both schooling success and that provide opportunities for shared engagement in developing programs that support each community’s distinctive sense of identity.

Notes

- 1.

The PICo criteria invaluably assist in identifying the research population, the phenomena of interest and the context, which is then used to guide defining the question and the subsequent Boolean search strategy used to locate potential research studies [see Petticrew and Roberts (2006, p. 38)].

- 2.

See Chap. 2 on methodology.

References

Auerbach, S. (2012). Conceptualising leadership for authentic partnerships. In S. Auerbach (Ed.), School leadership for authentic family and community partnerships: Research perspectives for transforming practice (pp. 31–77). Routledge.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). SCSEEC successful school attendance strategies evidence-based project: Literature review. AIHW.

Barr, J., & Saltmarsh, S. (2014). “It all comes down to the leadership”: The role of the school principal in fostering parent-school engagement. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 42(4), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213502189

Battiste, M. (2004). Unfolding the lessons of colonisation. In C. Sugars (Ed.), Unhomely states: Theorizing English-Canadian postcolonialism (pp. 209–217). Broadview Press.

Bennet, M., & Moriarty, B. (2015). Language, relationships and pedagogical practices: pre-service teachers in an Indigenous Australian context. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/22040552.2015.1084672

Berthelsen, D., & Walker, S. (2008). Parents’ involvement in their children’s education. Family Matters, 79, 34–41.

Bond, H. (2010). “We’re the mob you should be listening to”: Aboriginal elders at Mornington Island speak up about productive relationships with visiting teachers. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000909

Chenhall, R., Holmes, C., Lea, T., Senior, K., & Wegner, A. (2011). Parent- school engagement: Exploring the concept of ‘invisible’ Indigenous parents in three North Australian school communities. The Northern Institute. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/1458/

Chodkiewicz, A., Widin, J., & Yasukawa, K. (2008). Engaging Aboriginal families to support student and community learning. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 2(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595690701752880

Cleveland, G., & Western Australian Aboriginal Education and Training Council, & Western Australia Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations. (2008). The voices of our people: Aboriginal communities across Western Australia speak out on school and community partnerships. Western Australian Aboriginal Education and Training Council.

Coughlan, M., Cronin, P., & Ryan, F. (2007). Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: quantitative research. British Journal of Nursing, 16(11), 658–663. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2007.16.11.23681

Department of Employment, Education and Training. (1989). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education policy: Joint policy statement. DEET. Accessed May 11, 2020, from http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/81579

Dockett, S., Mason, T., & Perry, B. (2006). Successful transition to school for Australian Aboriginal children. Childhood Education, 82(3), 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2006.10521365

Ewing, B. (2012). Funds of knowledge of sorting and patterning: Networks of exchange in a Torres Strait Island community. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.20

Fogarty, W., Bulloch, H., McDonnell, S., & Davis, M. (2018). Deficit discourse and indigenous health: How narrative framings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are reproduced in policy. Lowitja Institute.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2012). An introduction to systematic reviews. Sage.

Guenther, J. (2011). Evaluation of FAST Galiwin’ku program. Cat Conatus. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14199.01443

Guenther, J., Disbray, S., & Osborne, S. (2015). Building on ‘red dirt’ perspectives: What counts as important for remote education? Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 44(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.20

Guenther, J., Harrison, N., & Burgess, C. (2019). Special issue. Aboriginal voices: Systematic reviews of indigenous education. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 207–2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00316-4

Harrison, N., & Murray, B. (2012). Reflective teaching practice in a Darug classroom: How teachers can build relationships with an Aboriginal community outside the school. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.14

Hayes, D., Johnston, K., Morris, K., Power, K., & Roberts, D. (2009). Difficult dialogue: Conversations with Aboriginal parents and caregivers. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 38(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000594

Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017). Checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Systematic_Reviews2017_0.pdf

Kamara, M. S. (2009). Indigenous female educational leaders in Northern Territory remote community schools: Issues in negotiating school community partnerships. (PhD Thesis). Australian Catholic University.

Lampert, J., Burnett, B., Martin, R., & McCrea, L. (2014). Lessons from a face-to-face meeting on embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander perspective: ‘A contract of intimacy’. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 39(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911403900111

Lea, T., Wegner, A., McRae-Williams, E., Chenhall, R., & Holmes, C. (2011). Problematising school space for Indigenous education: Teachers’ and Parents’ perspectives. Ethnography and Education, 6(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2011.610579

Lewthwaite, B. E., Osborne, B., Lloyd, N., Boon, H., & Llewellyn, L. (2015). Seeking a pedagogy of difference: What Aboriginal students and their parents in North Queensland say about teaching and their learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(5), 132–159. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n5.8

Lovett, S., Dempster, N., & Fluckiger, B. (2014). Educational leadership with Indigenous partners. Leading and Managing, 20(1), 1–10.

Lowe, K. (2011). A critique of school and Aboriginal community partnerships. In N. Purdie, G. Milgate, & H. R. Bell (Eds.), Two way teaching and learning: Toward culturally reflective and relevant education (pp. 13–32). ACER Press.

Lowe, K. (2017). Walanbaa warramildanha: The impact of authentic Aboriginal community and school engagement on teachers’ professional knowledge. Australian Educational Researcher, 44(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0229-8

Maxwell, J. (2012). Teachers, time, staff and money: Committing to community consultation in high schools. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.31

Mechielsen, J., Galbraith, M., & White, A. (2014). Reclaiming indigenous youth in Australia: Families and schools together. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 23(2), 35–41.

Muller, D. (2012). Parents as partners in Indigenous children’s learning. Family-School and Community Partnerships Bureau. http://familyschool.org.au/files/5113/7955/4822/parents-as-partners-in-indigenous-childrens-learning.pdf

Muller, D., & Saulwick, I. (2006). Family-school partnerships project: A qualitative and quantitative study. Department of Education, Science and Training. http://familyschool.org.au/files/6613/7955/4781/muller.pdf

Munns, G., O'Rourke, V., & Bodkin-Andrews, G. (2013). Seeding success: Schools that work for aboriginal students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 42(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2013.6

National Curriculum Services. (2012). What works. The work program. Success in remote schools: A research study of eleven improving remote schools. National Curriculum Services. http://www.whatworks.edu.au/upload/1341805220784_file_SuccessinRemoteSchools2012.pdf

NSW AECG & NSW DET. (1999). Securing a collaborative partnership into the future: Consolidating a 21 year working relationship. NSW Department of Education and Training and NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group.

NSW AECG & NSW DET. (2010). Together we are; together we can; together we will: Maintaining a collaborative partnership into the future. Partnership agreement 2010–2020. NSW Department of Education and Training. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/aec/media/documents/partnershipagreement.pdf

NSW Department of Education & Communities. (2012). Connected communities strategy. Department of Education & Communities. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/aec/media/documents/connectedcommunitiesstrategy.pdf

NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs. (2013). OCHRE: NSW Government Plan for Aboriginal Affairs: Education, employment & accountability. http://www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/nsw-government-aboriginal-affairs-strategy

Owens, K. (2015). Changing the teaching of mathematics for improved indigenous education in a rural Australian city. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 18(1), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-014-9271-x

Patrick, R., & Moodie, N. (2016). Indigenous education policy discourses in Australia. In T. Barkatsas & A. Bertram (Eds.), Global learning in the 21st century (pp. 165–184). Sense Publishers.

Perso, T., Kenyon, P., & Darrough, N. (2012). Transitioning Indigenous students to western schooling: A culturally responsive program. Paper presented at the 17th Annual Values and Leadership Conference: Ethical Leadership: Building Capacity for those Moments of Challenging Choices, Brisbane.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing.

Sanderson, V., & Allard, A. (2001). ‘Research as dialogue’ and cross cultural consultations: confronting relations of power. Paper presented at the AARE 2001 Conference, Melbourne.

Smith, J. A., Larkin, S., Yibarbuk, D., & Guenther, J. (2017). What do we know about community engagement in Indigenous education contexts and how might this impact on pathways into higher education? In J. Frawley, S. Larkin, & J. A. Smith (Eds.), Indigenous pathways, transitions and participation in higher education: From policy to practice (pp. 31–44). Springer.

Vass, G. (2017). Preparing for culturally responsive schooling: Initial teacher educators into the fray. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(5), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117702578

Woodrow, C., Somerville, M., Naidoo, L., & Power, K. (2016). Researching parent engagement: A qualitative field study. The Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University.

Yunkaporta, T., & McGinty, S. (2009). Reclaiming aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface. Australian Educational Researcher, 36(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216899

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lowe, K., Harrison, N., Tennent, C., Guenther, J., Vass, G., Moodie, N. (2023). Improving School Engagement with Indigenous Communities. In: Moodie, N., Lowe, K., Dixon, R., Trimmer, K. (eds) Assessing the Evidence in Indigenous Education Research. Postcolonial Studies in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14306-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14306-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-14305-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-14306-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)