Abstract

Most learning theorists now view learning as a fundamental intertwining of social, cultural, and historical processes, and have observed this intertwining (Barton and Tan, J Res Sci Teach 46:50–73, 2009; Rahm in Understanding interactions at science centers and museums. Sense Publishers, 2012) in museums and elsewhere. Here, we will use sociocultural theory and cultural historical activity theory, CHAT as our foundation and analytic tool (Engeström, 1987, 2006; Engeström & Sannino, 2011), to look closely at learning at three levels of analysis: family activity, visitor/educator activities and field-based teaching activity. Using three case studies of conflict and change, we examine how CHAT provides a comprehensive theory that can integrate complex and often conflicting aspects of learning and teaching in out of school settings. We focus our analysis on contradictions, most specifically as they play out across the personal, professional, and institutional levels, involving curricular, social, ideological and cultural tensions. We emphasize the concept of expansive learning, noting in particular how theoretical constructs and practices are intertwined, as we use abstract ideas to understand concrete practices and vice versa. CHAT allows us to consider contexts, people, and their mediational means and goals, without losing sight of the whole.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Views of classroom learning have shifted considerably over the past century, from behaviorism to constructivism, the cognitive revolution, sociocultural theory and Vygotsky (1987), community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991), and cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) (Engeström, 1987), to name but a few. Over time each has trickled down to informal settings. The above list also signals the important shift from an individual to a social emphasis in learning research. We underscore the need for a rich intertwining of social and cultural processes, using a powerful theoretical frame to cut through the many layers of involvement, and one that uses a unit of analysis large enough to be meaningful; for us, the irreducible minimum is the activity system itself (Foot, 2014). Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) keeps entire systems in mind, thus not limiting our analysis. One goal of this chapter is to make CHAT’s ideas, tools, and language more accessible, both to museum professionals using it in their everyday teaching and to administrators working to transform how they view learning in their institutions. This chapter provides three everyday examples of CHAT analysis.

We first provide a brief overview of key theoretical aspects of CHAT, then describe how the principles of contradiction and expansive learning can be applied to the work we do in informal settings.

Changing learning perspectives is not easy. Janes (2013) used the terms, complexity, uncertainty, nonlinearity, emergence, chaos, and paradox to characterize museum change. The ways we characterize learning typically reflect our own learning processes, our experiences in formal schooling, and those learning theories we are trained to use (Bransford et al., 1999). Learning, for some, focuses on the individual; for others, on behavior; and for others, still on brain function. As informal learning institutions across the world are struggling to adapt to twenty-first century sociopolitical realities, such as shifting demographics and uncertain finances, they are also being challenged to more genuinely embrace socioculturally- and equity-informed learning and teaching practices (Ash, 2022; Dawson, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c). As museums wrestle with financial survival, Covid 19, and shifting demographics, we ask what it means to learn to exist within these new realities and how organizational learning can transform.

Once described by Engeström as ‘the best kept secret in academia’ (1993, p. 64), CHAT has more recently been applied to informal settings or learning out of school. CHAT is becoming increasingly important in analyses of change, applied to labs, hospitals, libraries, classrooms, and, of course, informal learning spaces (Ash, 2022; deGregoria Kelly, 2009; Yamagata-Lynch, 2010; Ward, 2016). Those who have written about organizational learning in informal learning environments locally, and institutional change more generally (Bennett, 2018; Engeström &; Sannino, 2011; Janes, 2013) argue that transformation must be dynamic, it takes time, history matters; it is hard to recognize barriers; piecemeal change is inadequate, and a comprehensive theoretical grounding is essential.

Increasingly, we are called to critically analyze our conceptions of learning and to reflect on how these ideas and practices uphold systems of oppression in education systems. More importantly, we are asked to develop new conceptions of learning that dismantle systems of oppression. In this sense, we are asked to do what we have not yet done and thus there is no roadmap. CHAT has demonstrated versatility as a theory of becoming that helps us to inform, support, and reciprocally intertwine practice and theory in fundamental and meaningful ways (Engeström, 1987, 1999). We use CHAT to hold and analyze complex systems because of its emphasis on dynamic analysis of how contradictions drive transformation (Engeström, 1987), its focus on dialectical relationships, and its capacity for studying many aspects of systems at once. In terms of museums, CHAT’s concept of expansive learning becomes central to understanding how change can occur sustainably in the face of mounting pressure to change.

To understand CHAT, we must first dip into sociocultural theory, sometimes known as the first-generation-of-activity theory (Engeström, 1987). Sociocultural theory is a psychology of becoming in which people experience both the social nature of their existence and the collective creative activity that results in the making of new tools for individual and social use (Holzman, 2006). This perspective assumes learners and social organizations exist in recursive and mutually constitutive relation to one another across time.

Founded by Lev Vygotksy, sociocultural theory initially focused on the significance of meaning-making, researching how people use cultural tools, for example shovels and typewriters, and semiotic tools such as language. Vygotsky understood the learning process as inherently social (Wertsch, 2007), whereby what we learn as individuals we internalize from our contexts, thus it first lives outside of us before moving inside. Famously, this occurs in the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which Vygotsky defined as the region of activity learners can navigate with aid from a supporting context, including but not limited to people (Vygotsky, 1987, in Brown et al. 1993), and that mediates between inner and outer worlds.

In addition to these ideas, sociocultural theory has roots in Marxism and thus dialectics become central to any understanding of sociocultural theory and its counterparts. Dialectical thought moves us away from thinking about the subject and the object as their own separate entities and instead makes us understand them as intertwined. It posits that we cannot understand the subject without the object. Engeström noted that struggles and contradictions regarding the object of the activity characterize activity system networks. Power reflects in administrative hierarchies, uneven division of labor, or salaries and roles. The current conception of Activity Theory reminds us to look for power relations in such struggles by analyzing structures and dynamics directly.

If someone were studying us writing this chapter right now, they would get an incomplete picture until they also understood the reader. As writers, we are incomplete without our intended readers. In the case of CHAT, ‘working the dialectic’ relies on uncovering relationships between activity systems or parts of them. Consistent with other sociocultural perspectives, CHAT allows one to see the world differently from most other learning/teaching theories, because it specifically invites us to see the dialectic within systems and to “grasp the systemic whole of an activity, not just its separate components” (Foot, 2014, p. 3).

Dialectical logic and developmental processes are dynamic, where outcomes are unpredictable, and change is constant. Mahn (2003) suggested that Vygotsky’s dialectical approach has four central tenets:

-

1.

We must examine phenomena as a part of a historical, developmental process from their origins to their terminus.

-

2.

We see change, a constant, most clearly at times of qualitative transformation in phenomena.

-

3.

These transformations take place through the unification of contradictory, distinct processes.

-

4.

We must analyze these unifications or unities through aspects that are irreducible and embody the essence of the whole.

CHAT’s unit of analysis includes the dynamic interplay of the social, cultural, and historical aspects of development. While Vygotsky’s work focused on individual development in context, the contemporary work of Yrgö Engeström describes how collectives and organizations develop through activity in context. CHAT’s unit of analysis, the activity system, is a representation of the social and historical organization of “object-oriented, collective, and culturally-mediated human activity” (Engeström & Miettienen, 1999, p. 9).

For CHAT scholars, activity is not simply a behavior; it is a process-as-a-whole, rather than a linear sequence of discrete actions (Foot, 2014). Thus, we must understand activity systems in their completeness as a unit of analysis that we cannot disaggregate (Leont’ev, 1978). This focus on the collective positions the work people do and how they build organizations as greatly affecting how they do the work and how others receive it. CHAT theorists understand the context of the activity system as not a container or shell in which people behave certain ways, instead it is the activity itself.

1.1 Activity Systems

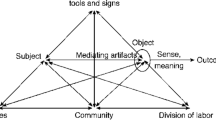

The first step in understanding CHAT is to understand the activity system (Fig. 4.1). The activity system is always evolving through learning actions that result as a response to the emergence of systemic contradictions. Five principles guide activity systems (Engeström, 2001):

-

1.

The main unit of analysis is the activity system (See Fig. 4.1).

-

2.

Multi-voicedness: Multiple perspectives, interests, and traditions are sources of both conflict and transformation.

-

3.

Historicity: The history of a system allows us to understand its problems and its potential.

-

4.

Contradictions: Contradictions drive the activity system as old and new come into conflict.

-

5.

Expansive learning: Transformations in activity encourage reconceptualization of the object and the motive of activity into something previously unanticipated. (Adapted from Murphy & Rodrigues-Manzanares, 2008.)

In the diagram (Fig. 4.1) of the activity system (Engeström, 1987) we see the subject, object, motive, division of labor, rules, tools, and community. Each of these six components is in a transactional and dialectical relationship with one another and the relationship between them creates various tensions that affect the system. To illustrate these six components, imagine a teacher leading their class to an aquarium on a field trip. The teacher and the class are the subject. The teacher wants to use the aquarium as a resource for connecting back to concepts they are teaching in their classroom—this is the object. When they get to the aquarium, the teacher uses their curriculum and the objects in the museum as tools to mediate student learning. They ask the students to fill out worksheets while they are in the aquarium based on what the museum labels say; these too are tools. Imagine also the class takes a tour with a guide; the guide and everyone in the aquarium are part of the community, all of whom engage around the object of teaching the students. Requirements, such as chaperones and a pre-lunch school return time, as well as the directions on the worksheets, all make up the rules of the system. Finally, labor is divided in this system between the guide giving the tour, the teacher, and the students and what they have been asked to accomplish. If any of these components is disrupted, it affects the entire system.

1.2 Contradictions

When we talk about learning in CHAT, we must talk about the concept of contradiction. Theorists situate contradictions (both between and within activity systems) as potential sources of change; they can function as valuable levers of change, rather than disturbances to avoid. Within CHAT, contradictions as they materialize in daily activity spark changes to the system (Foot & Groleau, 2011). Contradictions are systemically, structurally, and personally experienced. They “manifest themselves as problems, ruptures, breakdowns, and clashes” and yet are “sources of development; activities are virtually always in the process of working through contradictions” (Kuutti, 1996, p. 34). Tensions in the system aggravate contradictions and they turn into concrete manifestations that affect the daily work of participants. We can understand contradictions as “places” in the activity system from which innovation is born (Foot, 2014). The extent to which members of the activity system can resolve or transcend the contradictions determines how an expansive cycle will be constrained or flourish. Contradictions are not places of failure; nor are they problems to fix through technical, practical solutions. Foot (2001) describes contradictions as illuminative hinges from which participants can gain new vistas of understanding. She uses the term “hinge” to describe how contradictions link fixed entities to a mobile entity, for example a door (mobile) attached to the frame of a house (fixed) (Foot, 2001, 2014).

There are four types of contradictions; first, all contradictions stem from the primary contradiction that occurs between the use-value and the exchange-value of a system (Engeström, 1987). Marx’s ideas about the use-value, that which gives work its inherent worth, versus the exchange-value, that which makes work a commodity, underline the primary contradiction. For example, a doctor provides a service of helping the ill (use-value) but to do so gets paid for that work (exchange-value).

Secondary contradictions exist between the nodes of the system and cause the dormant primary contradiction to emerge, as tension forms between two different parts of the activity system. Tertiary contradictions become apparent when the object of a more “culturally advanced” activity (Engeström, 1987) is introduced to the system. For example, an employee requests that a learning organization puts out a statement in support of Black Lives Matter. Finally, the quaternary contradiction is when two activity systems intersect. The quaternary contradiction arises when neighboring activity systems feel the effect of attempts to resolve a tertiary contradiction (Engeström, 1987; Foot & Groleau, 2011).

By identifying the levels of the contradictions and not treating the contradictions as all the same, we begin to understand how aggravating one level leads to another aggravated level while uncovering some of the interconnectedness of the system in question. To do this kind of work requires two different focuses, one that considers the historicity of a system and another that allows the system a chance to imagine what it can become.

2 Expansive Learning

Expansive learning is the process of creating new objects of activity, those as yet undefined. We achieve this kind of learning through specific learning actions:

-

1.

Questioning, criticizing, or rejecting aspects of the current accepted practice and wisdom

-

2.

Analyzing the situation through mental, discursive, or practical transformation to understand what is happening. This occurs through either or both: a historical-genetic analysis that seeks to explain the situation by tracing its origins and evolution, or an actual-empirical empirical analysis that seeks to explain the situation through the representation of the activity system’s inner systemic relations.

-

3.

Modeling the discovered relationship through some publicly observable and transmittable medium

-

4.

Examining and experimenting on the model to understand its dynamics, potentials, and limitations

-

5.

Implementing the model in practice, enrichments, and conceptual extensions

-

6.

Reflecting on and evaluating the process

-

7.

Consolidating the outcomes into a new and stable form of practice (adapted from Engeström, 2014)

This cycle walks us through the expected stages of change as activity systems encounter contradictions, new goals, mediational means, practices, epistemological views, etc. We note that contradictions in any activity system may be aggravated when participants question the established norm (stage 1), especially if new practices radically deviate from previous activity. By aggravated we mean one of the ways in which conflict occurs, for example, different modalities for teaching, designing an exhibit, how much money to charge, which story to tell, and so on. The expansive cycle works with these aggravated areas.

When we seek to understand situations in which “whole collective activity systems, such as work processes and organizations, need to redefine themselves, [and] traditional modes of learning are not enough” (Engeström, 1999, p. 3), expansive learning becomes a powerful concept. “Nobody knows exactly what needs to be learned. The design of the new activity and the acquisition of the knowledge and skills it requires are increasingly intertwined” (Engeström, 1999, p. 3).

3 CHAT in Practice

CHAT has proven to be a powerful theoretical tool in our own work and research. Below we provide three examples that demonstrate some of the ways a CHAT stance toward people, mediational means, object/outcome, rules, division of labor, and community informs how we more flexibly can situate institutional learning in informal learning settings. CHAT provides practical tools for recognizing how components of a system interact and inform each other in dynamic and sometimes unexpected ways. This characteristic of CHAT makes the theoretical eminently personal and practical.

We address three levels of analysis. First, collaborative family learning showcasing the dialectic between individual and the collective in learning activity at a science exhibit. Second, we see the contradiction and the dialectic in teaching ethos, considering teaching as telling versus teaching as scaffolding. We note educators’ role in institutional transformation. Last, we discuss equitable teaching in field-based/environmental education, as two activity systems interact when negotiating the meaning of equity for the program. All names in the three cases are pseudonyms.

3.1 Case 1: What Are We Supposed to Do Here?

The first example shows how practitioners and researchers can analyze family activity using sociocultural theory/CHAT to interpret collective activity, recognizing the dialectic between the individual and the collective, the inherent role of mediational means in any activity, and different socio-historic roles in the family system. This is an important first step in adopting an activity systems stance.

Observing families as they made sense of science allows us to see the learning activity systems in situ, especially their dynamics and tensions, but also the ‘repertoires of practice’ the families bring to museums. By ‘linguistic and cultural-historical repertoires of practice’ Gutierrez and Rogoff refer to moving beyond individual ‘styles of learning’ toward experience, by focusing researchers’ and practitioners’ attention on variations in individuals and groups’ histories of engagement in cultural practices because the variations reside not as traits of individuals or collections of individuals, but as proclivities of people with certain histories of engagement with specific cultural activities. Thus, individuals’ and groups’ experience in activities—not their traits—becomes the focus (2003, p.19).

Using experience as focus, we recognize how rules, in this case determining their own ‘rules’ of engagement’ was an essential initial task.

The vignette, a short summary of a digital video-captured segment (1:37 min) of a longer visit at an interactive science exhibit, was captured at an urban museum of science and industry in south central Florida as part of an NSF-funded, equity-oriented, professional development intervention program. The family was audio- and video-taped naturalistically as they visited a subset of four exhibits; here we look at one exhibit, the DINO-Saurus, a large (3 ft × 5ft) dinosaur head with an open mouth and detachable plastic teeth, surrounded by two tables displaying samples of meat-eating and plant-eating animals’ teeth. There was minimal signage.

The Aarons family (four children and a mother) initiated their visit with a question concerning how the family might use the exhibit. We now call this specific practice ‘figuring out’, an activity typically marked discursively by something like the “What are we supposed to be doing?”, posed here by Leticia (13-year-old), as they approached the DINO-Saurus exhibit (Mai & Ash, 2012). After a period of uncertainty, and with much discussion and laughter, they collaboratively put the plastic teeth in the Dino mouth. Leticia said very little as she directed her younger brother Pedro (6-year-old), giving him some plastic teeth to place in the spot toward the back of the dinosaur’s mouth. At that point Pedro turned to his mother, who stood next to him and also was placing teeth in the dinosaur’s mouth, telling her the teeth she was holding were molars.

Mother: How do you know those are the molars?

Pedro: Cause I know.

Mother: Did your teacher tell you?

Pedro: [laughing] Yes.

Soon after that exchange, the youngest brother, “Norman” (5-year-old), jokingly punched the dinosaur with his older brother, “Karl” (12-year-old). His mother directed him to stop and join the others in the teeth placement activity. Norman joined Pedro and started to put the teeth in while Karl watched them from behind.

Pedro: No, look, lookit, lookit, look what I’m, what I’m doing! You twist it in.

Pedro guided Norman to put the teeth in a certain way so they would not easily fall out.

As he watched Pedro, Norman objected.

Norman: No! The sharp teeth ain’t supposed to go up there!

Pedro: No, up!”

The two struggled to place the teeth.

At this point, the mother said

Mother: You can put them in any way you want. Let's look at these right here.

She got up and walked over to the other area of display and the boys followed.

(Aarons family at DINO-Saurus, Mai & Ash, 2012, p. 98)

The subjects are the Aaron's family members, while the mediational means are a dinosaur head, sample teeth, dialogue, signs, and gestures. The first object/goal was to ‘figure out’ how the exhibit was supposed to be used; once that was accomplished the family talked about content, e.g., molars. The rules of ‘how to do’ the exhibit were not available, nor were there educators to guide them. The family had not been to this museum before, nor were they frequent museumgoers. The surrounding community of other visitors, researchers, and staff were visible, and the division of labor in the family system was fluid, as it often is in social teaching and learning. As Foot and Groleau (2011) describe such an activity system:

...the object is both something given and something anticipated.... Subjects are individuals or groups [use tools] striving to attain or engage the object...The concept of tool in CHAT groups together elements of various natures— all of which mediate the subject–object relationship...The community of significant others …[are] multiple individuals and groups who share an orientation to and engagement with a common object…the rules, whether explicit or not, regulate the subject’s actions toward the object and relations between members of the community...The division of labor — what is done by whom — describes how the community structures its efforts to engage the object... (pp. 1-2)

We have argued that ‘figuring out’ is a cultural historical ‘repertoire of practice’ (Ash, 2022; Gutierrez & Rogoff, 2003; Mai & Ash, 2012) that families new to museums use when faced with the challenge of using exhibits without knowing the language of museums, or the overt and covert rules. Leticia’s question externalized what may have been on the minds of all family members. Such scenes, repeated by many other non-dominant families new to museums in our research in other settings, have taught us that families navigate museums in their own way, attempting to understand the explicit and implicit rules (so as not to do it wrong), using sometimes unexpected social, cultural, and historical repertoires and resources (Ash, 2014a, 2014b; Mai & Ash, 2012). This is not surprising.

Returning to Fig. 4.1, we note division of labor2 in the social organization; family members engaged in related but not entirely overlapping actions. Pedro knew things about molars the others did not know. Leticia got the family started and named the activity (figuring out how to do the exhibit). Of the others, the mother, and eventually Norman, were supportive, but Karl was not (punching the head). Knowledge and action were distributed across family members.

This episode and others like it remind us how conceptualizing the ever-shifting landscape, as Vossoughi and Gutierrez (2014) suggest, allows us to “unsettle normative definitions of learning’, to move ‘beyond reductive dichotomies and… focus on the multiple activity systems in which people develop repertoires of practice” (p. 605). By ‘linguistic and cultural-historical repertoires’ we mean “the ways of engaging in activities stemming from observing and otherwise participating in cultural practices” (p. 22).

Analyzing the Aarons family interaction helps us move beyond reductive dichotomies. Was the learning individual or collective, both, or neither? Dialectical reciprocal relationships between individual and social, as in this example, are an essential intertwining, or as Mahn (2003) said, “the unification of contradictory, distinct processes” (p. 192), which refers to the way families inform, question, explain, and gesture, often creating events that we may not have expected.

We note the tension between subject(s) and rules, signaling the emergence of a secondary contradiction; for example, what are visitors new to museums supposed to do if the invisible rules of hands-on exhibits, which are so often taken for granted, are not provided? Shall we interpret them as doing it wrong or shall we, instead, search for repertoires we may not have recognized before? We may not ‘notice’ exactly how and when nontraditional families construct and/or display such repertoires, especially if we are not taught how to spot them (Mai & Ash, 2012). As Bogost (2018) argued, “After all, people have areas in their own lives in which they are the experts. Everyone is capable of deep understanding” (p. 2). Beyond an anti-deficit view, this argument asks that we think equitably, that is providing resources according to need. What if norms differed and expectations were not standard European-American? People can and do ‘fail’ at museums the way they are currently structured.

Dawson noted that European-American epistemologies get in the way of our interpretations of what is happening in museum settings; she fears we are blind to the things we are not in the habit of noticing (). As Dawson argues, we need not view such unknowing as a ‘barrier’; such metaphors get in the way of what is happening. This episode is provided to ‘open our eyes’ to a family activity system in action, meant to counteract settled expectations, which Bang and Marin (2015) suggest are: “the set of assumptions, privileges, and benefits that accompany the status…’that whites have come to expect and rely on’ (Harris, 1995, p. 277) across the many contexts of daily life” (Bang & Marin, 2015, p. 532).

While we may have been unaware of the embedded norms (Moore, 2013) and settled expectations (Bang & Marin, 2015; Bang et al., 2012) that have, in the past, and still currently reflect the status and power of in-groups in museums and all informal institutions, we do now know. We use CHAT to look closely at how contradictions between expectations and actuality help us to ‘see’ such power dynamics more clearly and hold the activity system as the focus.

3.2 Case 2: A Tale of Two Shirts

In this second example, we explore contradictions in a years-long research project involving museum educator professional development theory and practice. As educators are often tasked with leading change in museums, this second case highlights their work, but is set within the wider museum system. The contradictions we suggest here are critical to our analysis, as they drive the system of expansive learning.

During this project, we trained a group of intervention educators (blue shirts) to question and analyze educator practices, in order to center their new model in equity. One theoretical cornerstone was scaffolding in the zone of proximal development (ZPD) (Vygotsky, 1987). They began by learning and practicing ethnographic watching and notetaking, emphasizing noticing visitors’ existing resources as visitors interacted on the floor, both with and without educators. One object/goal of their work was “to incorporate the… voices [of those who are] marginalized in research and institutions that make up the informal infrastructure” (Ash & Rahm, 2012, p. 4), to conduct action research on their own practice, to be critically reflective (Ash, 2019), as well as to design and test new teaching/scaffolding practices with visitors (Ash & Lombana, 2012).

While these blue-shirted educators were doing this work, another group of regular educators (purple shirts) continued to educate visitors using a lecture, showman form of teaching, focusing on content transmission, often using scripts. They had been asked to teach forcefully and to be noticed by visitors (Ash & Lombana, 2012). In this sense, visitors to the museum were seen as “needing to know”, so the work of the educators was to provide that knowledge. Some of the blues also worked as purples. All educators were paid.

Unsurprisingly, these two different approaches to learning and teaching led to tensions, and thus contradiction between the two groups, which also reverberated in the larger museum. A few blue shirt educators had negative experiences with purple shirt mid–level administrators and shared their unease with the whole blue group. Some blues had been hired as purple educators during the first year of the project. The blues realized just how different the blues and purples were; they experienced different work expectations, power, agency, and identities concerning their roles as educators. They felt like purple-shirt training was asking them to be loud, and to ‘perform’. Sally, a recent college graduate who briefly had been a purple shirt, saw that a purple shirt mid-level manager was displeased with her work. She took the purple shirt job to make extra money. This was short lived, because the following happened.

I went to one of my (purple shirt) bosses and asked, ‘What am I doing wrong that is causing this friction?’ (hand gestures, showing the manager waving her away). I went to another purple shirt and asked if that really happened (being waved away). So, they went and tried and said that they got the same response. The person basically told us that we would talk about it later. It was humiliating. It was when I was a purple shirt.

Marie, who had never been a purple shirt, argued:

I feel like they [purple shirts] are trying to standardize an approach. But what we’ve [blues] learned in here is that a standardized approach doesn’t work; it has to be individualized, customized. You have to take cues from the guests. It alienates people when you don’t take their individual style into account.

As the blue shirts learned during the first year of the research intervention, changing a ‘teaching system’ is hard. The more powerful purple power structure resisted their work. The intervention study was well funded and therefore accepted by most administrators, yet mid-level managers resisted. Museums and informal learning settings pour resources and funding into developing new practices, but often without looking at how those practices might impact or be impeded by the already existing systems. This case is one example of what change scholars such as Gutierrez and Barton (2015), and Engeström et al. (1999) mean when they refer to the problems that can arise when attempting to transform work organizations.

To disrupt traditional power structures, we must examine the often-implicit messaging of ‘business as usual’, relative to museum professionals’ work, and then reposition these within both contradictory and dialectical frames. Here the dialectic most directly concerned ‘telling versus scaffolding’ as dominant teaching practice. Educators tasked with leading transformation efforts, both for themselves and for their institutions, were caught in the contradiction between rules and object/outcome. Historically, socio-politically-formed expectations are appropriated with little understanding of the dialectical nature of systemic change, which incorporates the historicity, intertwined relationships, and contradictions intrinsic to change. CHAT analysis captures all this complexity in analyzing and to some degree anticipating the course of change. Therefore, when planning new interventions, we must anticipate sources of potential resistance within the existing structures and institutional culture, identify them and bring them into the scope of the intervention.

3.3 Case 3: Negotiating Equity Across Activity Systems

This third case concerns a research intervention that started with the question: “What is equitable field-based/environmental education (EFBEE)?”. This project challenged dominant and normed discourse of equity and asked pre-service science teachers (PSSTs) to conceptualize informal outdoor education as a space of equity and inclusion. We drew data from the pilot year of a professional development program collaboration of an Education Department, Biology Department, the Natural Reserve System of a University system, and the local County Office of Education. Data included pre/post interviews, quarterly reflective journals, ethnographic field notes of workshops, associated MA/C student coursework (including research papers and lesson plans), and reflective presentations (Ash & Race, 2021).

As the program progressed, we noticed that while all partners had the same object/goal of preparing teachers to teach equitable field-based lessons, ideas of how to reach that goal differed, as did the definitions for key concepts, such as equity and resources. While this is not uncommon in interdisciplinary collaborations, the question became how to attend to competing ideologies without privileging western ways of doing and talking science. As researchers, we needed a way to understand how these differences emerged in the program and how the contradiction impacted pre-service teachers’ ability to achieve the program goal.

One place this tension emerged was in the types of mediational means/tools the different partners saw as valuable to achieving the object/goal. For the education department, the tools aimed at social justice and equity, often challenging normative science education. We asked PSSTs to critically reflect on their own identities and those of their students. For the Natural Sciences Department, resources originally focused on examples of successful field-based lessons offered in higher education settings. Already vetted with college students, these activities were scientifically accurate and workable, so why should they not work with the pre-service science teachers (PSST) and their K-12 students? This represented a classic view of providing equal but not equitable resources. The mismatch of meanings emerged most clearly in the quarterly workshops originally led by natural science faculty. The pre-service science teachers, steeped in a social-justice-and-equity stance in their MA/C program, noticed the conflict. Cheyanne said:

A lot of the kids that they're (university science professors) working with, it's not equitable…Let's talk about K-12 when we're working with kids of all levels, all backgrounds. That's where the conversation on equity needs to be happening.

Another PSST Sandy said:

…I think that [equity] is what the cooperating teachers [CTs] and the student teachers [PSSTs] wanted. I think everyone associated with the master’s program, that’s what they wanted. But the people that we brought in weren’t addressing those issues. And I think just re-aligning what the overarching goal is for everyone, including participants [and] guest speakers about why we are speaking at this specific workshop would be better and put everyone on the same page.

Cheyanne and Sandy recognized that using the same pedagogical approach with K-12 and university students did not consider the many additional and sometimes unknown challenges of equity goals. In short, these activities were not equitable. Near the end of the program, Cheyanne said this about FBEE and equity:

We can’t always take students into the field, but we can always bring the field to them... I think the group needs to spend more time unpacking that. That statement is a statement of equity as we try to compose a method of learning science that can be beneficial to all students across the whole world. And ...not all classrooms have the ability to go to a nature reserve every year. So, I would love to spend more time figuring out tangible ways of bringing the field to my classroom.

This stated tension between program goals and actual new ideas for implementation forced us to step back and systematically analyze the inequity in the essential resources provided to PSSTs. Many program leaders, despite best intentions for equity, often saw resources as generic field-based pedagogical tools, giving little thought to the specific level of instruction. Yet, Cheyanne noted, a key aspect of creating equitable FBEE is understanding how teachers practice equitable pedagogy, expand their local contexts, and use mediational means in new ways.

How does CHAT treat this complex situation? This Field-Based/Environmental Education Project contained multiple activity systems, a network of systems that came together to develop and support this program. We do not analyze the complete network but instead comment on the first-year collaboration between Education and Natural Sciences departments, to clarify how we can use CHAT to understand the contradiction that pushed eventual transformation.

We see in Fig. 4.2 that the triangle on the left has object 1, the second triangle, object 2, and the third new negotiated object will be object 3. The point of this diagram is that more than one activity system can negotiate the meaning of an object; here two University departments are trying to collaborate on what equity-based field/environmental lessons might entail (object 3). This contradiction motivated the PSSTs to advocate for change, which eventuated in a new emphasis for the next year’s program, during which negotiating the meaning of equity occurred early and often.

Two interacting activity systems as a minimal model for the third generation of activity theory (adapted from Engeström, 1999)

One of the larger lessons of this case involves the tensions created when equity, not equality, is the object. First, we saw two activity systems attempt to negotiate common meaning; this is a common but underappreciated activity. Moreover, larger networks are important. We could have included other systems, for example, the county, the land reserve, or the university administrations, among others, perhaps with varying views of equity. CHAT’s principle of multivoicedness can include the voices of many.

The degree of complexity we observed in activity systems of human/natural resources interaction is only one take-home lesson. Because the activity is the unit of analysis, a systemic view frees researchers from isolating single factors and validates what we already know is true—in any classroom, museum, or other workplace setting, there are always multiple competing, socially and historically informed ideological pressures on any one individual, staff, funder, exhibit designer, or member of the board of directors. In other words, viewing different activity systems as they interact is invaluable for equity-oriented, humanist research, making it an effective tool for analyzing power dynamics.

3.4 What Do These Three Cases Have in Common; How Do They Work Together?

CHAT is first and foremost a tool for systems analysis informed by seemingly complex notions, such as contradiction and dialectics. But, as we have seen in these three cases, CHAT analyzes at the personal, professional and institutional levels. We also note that we need not let fear of theory corral us into reverting to known strategies or simplistic practices that seem to ‘work’. Simple solutions often miss the mark (Foot, 2014). These three cases: setting agendas for family learning activities; the dialectic between didactic vs. scaffolded teaching; and negotiating the language and meaning of equitable field-based teaching, might seem at first glance to have little in common. Here we tease out some commonalities.

-

Each case was complex, involving multiple subjects, desired objects-outcomes, mediational means, community and so on. Such nodes, moreover, often are in tension or conflict. We may consider ‘museum curriculum’ a form of mediational means or as a negotiated object; further, the ‘rule’ of using only standard museum or field curriculum as mediational means in each of these three cases, constrained visitors, museum educators and preservice teachers. The subsequent resistance came in various forms, seemingly focused on changing the rules, object and/or the mediational means. When such nodes were challenged or resisted in all three cases, in attempts to change the ‘standard curriculum’ or the rules surrounding it, then change was hampered, and further tensions and conflict eventuated. Such a questioning of and resistance to what had been considered ‘basic teaching and learning content’ became essential to any subsequent transformation in each case.

-

Each case strongly relied on the cultural historical past, which served as key context and informant to current and ‘future repertoires of practice’, ideological commitments, as well affordances and limitations to collective agency (see Ash, 2022). The family attempted to create a hybridized curriculum. The museum and the field-based educators attempted to create new tools for teaching. In each case ideological commitments based on long-standing historical conflicts came into play. For example, in museums a deficit views of minoritized learners can eventuate in foisting standard curriculum based on White middle class ideologies on visitors, educators and managers (Ash, 2022; Dawson, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c).

-

By using sociocultural/CHAT theory to explore each case, new and generative questions arose: Case 1. Sociocultural/CHAT-How to do exhibits?; Case 2. CHAT- How to teach at an exhibit?; 3. CHAT- How to hybridize ideological differences?. Core ideological positions informed these three cases, for example resource vs. deficit views of minoritized learners. Theory both informed these new questions but also was informed by them. We used different aspects of CHAT to unpack the internal working of each system, yet underlying principles such as dialectical relationships between agency/structural constraints informed each case. Moreover, we witnessed inequality and contradictions of power reflected in competing ways of being, doing and thinking, and reflected in the discourse surrounding these efforts.

4 Discussion/Importance to the Field

Which learning theories do we rely on in informal and field-based settings? Will these theories suffice to inform our examination of equity in the face of current demographics? Informal learning environments are caught in a moment of unprecedented change and upheaval; using CHAT as a theoretical tool helps us remember that all the tensions and contradictions we are experiencing are an inherent part of activity systems. Our job is to work with them. Moreover, while we personally and individually may not feel the impacts, a systemic view orients us toward the real need, rather than any perceived need.

Most learning theorists now view learning as a fundamental intertwining of social and cultural. Cultural-historical activity theory or CHAT does that, and also adds historicity and the dialectic (Barton & Tan, 2009; Rahm, 2012). CHAT provides a comprehensive theory that can integrate many complex aspects of learning, as well as many and different levels of analysis.

CHAT seeks out and traces ‘contradictions’, understanding they are the persistent historical tensions that accumulate over time. When contradictions are noticeable in the system, they are emergent opportunities for change and fundamental components of the system that drive ‘expansive learning’ cycles (Engeström, 1997). In the cases in this chapter, we traced three such pathways that may inform practice.

Museums and other informal contexts are looking for systemic insights, pursuing a better understanding of teaching practices that reflect learning theories, yet museums are rarely reflective or critical of their practices (Janes, 2009, 2013). This inhibits their ability to organize toward meaningful and lasting change. CHAT design provides scaffolding for museums and other informal institutions to organize toward lasting change. To change, institutions first need to recognize accurately what must change and where within the organization.

CHAT provides useful tools for institutional critical reflection for change. For example, CHAT provides a way to explore dialectics of power (Dubin, 2014; Roth et al., 2012). By this we mean that power is involved in the inner workings of any activity system, where rules, hierarchies, and competing ideologies are involved, often resulting in dynamic and unpredictable outcomes. This sets the stage for dialogue concerning power differentials as they manifest at all levels of function.

CHAT allows us to examine multi-layered, contradictory events like the equity-based field/environmental education intervention, the intervention for training educators to work with equity, and the creation of a new lens for understanding cooperative family learning activity. Such examination reveals underlying philosophies, the roles and creation of mediational means, rules, communities, as well as hierarchies and goals. It is useful to frame contradictions in more practical terms, to make it easier to deal with often gnarly issues that arise in the course of change.

We are challenged to recognize the hidden ideologies and power dynamics underlying and affecting such events. CHAT allows us great freedom to explore how informal institutions work as systems, including identifying the sources and influence of power within the system and acting upon the system. CHAT provides scaffolding for museums to do that reflective work as they engage in the creative production of new ways of being in the world. This chapter informs our research community by demonstrating how CHAT can be a helpful tool to analyze learning and systemic change.

Given that informal learning environments are caught in a moment of unprecedented change and upheaval, using CHAT as a theoretical tool will help researchers and museum personnel understand change processes and will guide their experience as they promote change. Though we are each personally and individually caught within our own frames of reference, CHAT’s systemic view orients us toward the obvious and the real needs of all involved, including those new to the existing systems.

References

Ash, D. (2022). Reculturing museums: Embrace conflict, create change, Routledge.

Ash, D. (2019). Reflective practice in action research: moving beyond the “standard model.” In L. Martin, L. Tran, & D. Ash (Eds.), The reflective museum practitioner: expanding practice in science museums (pp. 23–38). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429025242-3

Ash, D. (2014a). Positioning informal learning research in museums within activity theory: From theory to practice and back again. Curator: The Museum Journal, 57, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.1205

Ash, D. (2014b). Creating hybrid spaces for talk: Humor as a resource learners bring to informal learning context. National Society for the Study of Education, 113(2), 535–555.

Ash D., & Lombana J. (2012). Methodologies for reflective practice and museum educator research. In D. Ash, J. Rahm, L. M. Melber (Eds.), Putting theory into practice. New directions in mathematics and science education, (Vol. 25). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-964-0_4

Ash, D., & Race, A. (2021). Paths toward hybridity between equity and field-based environmental education for novice science teachers. International Journal of Informal Science and Environmental Learning, 1(1), 1–19.

Ash, D., & Rahm, J. (2012). Introduction: Tools for research in informal settings. In D. Ash, J Rahm, & L. Melber (Eds.), From theory to practice: Tools for research in informal settings. Sense.

Bang, M., & Marin, A. (2015). Nature-culture constructs in science learning: Human/non-human agency and intentionality. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(4), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21204

Bang, M., Warren, B., Rosebery, A. S., & Medin, D. (2012). Desettling expectations in science education. Human Development, 55(5–6), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345322

Barton, A. C., & Tan, E. (2009). Funds of knowledge and discourses and hybrid space. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(1), 50–73.

Bennett, T. (2018). Museums, power and knowledge: Selected essays. Routledge

Bogost, I. (2018, October 26). The myth of ‘dumbing down’. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/10/scholars-shouldnt-fear-dumbing-down-public/573979/

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (1999). How people learn. National Academy Press.

Brown, A. L., Ash, D., Rutherford, M., Nakagawa, K., Gordon, A., & Campione, J. C. (1993). Distributed expertise in the classroom. In G. Solomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 188–228). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dawson, E. (2014a). “Not designed for us”: How science museums and science centers socially exclude low-income, minority ethnic groups. Science Education, 98(6), 981–1008. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21133

Dawson, E. (2014b). Equity in formal science education: Developing an access and equity framework for science museums and science centres. Studies in Science Education, 50(2), 209–247.

Dawson, E. (2014c). Reframing social exclusion from science communication: Moving away from “barriers” towards a more complex perspective. Journal of Science Communication, 13(2), 1–5.

deGregoria Kelly, L. A. (2009). Action research as professional development for zoo educators. Visitor Studies, 12(1), 30–46.

Dubin, S. (1999, 2014). Displays of power: Memory and amnesia in the American Museum. New York University Press.

Engestrӧm, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding. An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (1999b). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory: Learning in doing: Social, cognitive and computational perspectives (pp. 19–38). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812774.003

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamäki R. (Eds.). (1999). Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24, 368–387.

Foot, K. A. (2001). Cultural-historical activity theory as practice theory: Illuminating the development of conflict-monitoring network. Communication Theory, 11(1), 56–83.

Foot, K. (2014). Cultural-historical activity theory: Exploring a theory to inform practice and research. Journal of Human Behavior in Social Environments, 12(3), 329–347.

Foot, K., & Groleau, C. (2011). Contradictions, transitions, and materiality in organizing processes: An activity theory perspective. First Monday, 16(6), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i6.3479

Gutiérrez, K. D., & Calabrese Barton, A. (2015). The possibilities and limits of the structure-agency dialectic in advancing science for all. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(4), 574–583.

Gutierrez, K., & Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational Researcher, 32(5), 19–25.

Harris, C. I. (1995). Whiteness as property. In K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas (Eds.), Critical race theory (pp. 276–291). The New Press.

Holzman, L. (2006). What kind of theory is activity theory? Theory and Psychology, 16(1), 5–11.

Janes, R. (2013). Museums and the paradox of change. Routledge.

Janes, R. (2009). Museums in a troubled world. Routledge.

Kuutti, K. (1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human– computer interaction research. In B. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human–computer interaction (pp. 17–44). MIT.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Prentice-Hall.

Mahn, H. (2003). Periods in child development: Vygotsky’s perspective, In L. S. Vygotsky (Eds.), Vygotsky's educational theory in cultural context. Cambridge University Press.

Mai, T., & Ash, D. (2012). Tracing our methodological steps: Making meaning of families’ hybrid “figuring out” practices at science museum exhibits. In D. Ash, J. Rahm, & L. Melber (Eds.), Putting theory into practice: Methodologies for informal learning research (pp. 97–117). Sense Publishers.

Moore, B. (2013). Understanding the ideology of normal: Making visible the ways in which educators think about students who seem different. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Colorado.

Murphy, E., & Rodríguez Manzanares, M. (2008). Using activity theory and its principle of contradictions to guide research in educational technology. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24.

Rahm, J. (2012) Science in the making at the margin: A multi-sited ethnography of learning and becoming in an afterschool program, a garden, and a math and science Upward Bound program. In E. Davidsson and A. Jakobsson, (Eds.), Understanding interactions at science centers and museums. Sense Publishers.

Roth, W. M., Radford, L., & LaCroix, L. (2012). Working with cultural-historical activity theory. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(2), Art. 23. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1814/3379

Vossoughi, S., & Gutiérrez, K. D. (2014). Studying movement, hybridity, and change: Toward a multi-sited sensibility for research on learning across contexts and borders. Teachers College Record, 116(14), 603–632.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. Plenum.

Ward, S. J. (2016). Understanding contradictions in times of change: A CHAT analysis in an art museum. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington]. Research Works Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/1773/37091

Wertsch, J. V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 178–192). Cambridge University Press.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2010). Activity systems analysis methods: Understanding complex learning environments. Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ash, D., Ward, S.J. (2023). Activity Theory in Informal Contexts: Contradictions Across Learning Contexts. In: Patrick, P.G. (eds) How People Learn in Informal Science Environments. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13291-9_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13291-9_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-13290-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-13291-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)