Abstract

The highly interconnected and global supply chains have faced tremendous challenges since 2019. Global conflicts, natural disasters, wars, and the COVID-19 pandemic repeatedly cause supply chain disruptions and pose major challenges for the globalized supply networks in regard to robustness and resilience. The increasing interconnectivity makes supply chains more vulnerable to disruption and it seems that the proverbial stone that falls into the water actually causes a flood at the other end of the supply chain. This enhances the requirement for an effective risk management. Based on a survey of 216 supply chain risk managers of European production firms, this study introduces the collaborative sharing of production and human resources as a method to recover from disruptions. Thereby, trust and commitment are identified as the core values for collaborative resource sharing to increase supply chain resilience. We propose a framework to explicate the main drivers for collaborative human resource and production sharing and give first practical recommendations for supply chain risk managers to support the process of the development of mitigation strategies to recover from supply chain disruptions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Collaborative resource sharing

- Supply chain risk management

- Rational view theory

- Supply chain resilience

- Intertwined supply network

4.1 Introduction

The increasing frequency of risks, higher uncertainty, and disruptions is one major challenge for supply chain management (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020). Due to the increasing connection between supply chain partners and the increasing complexity even small disturbances lead to sensitive interruptions. Due to delivery shortages for electronic components from Ukraine production locations several car manufactures and automotive suppliers had to shut down their assembly lines in Germany and had to register short-time work (Piller, 2022). Apple had to shut down some production sites as their top manufacturer Foxconn in Shenzhen had to close its factory due to the resurgent COVID-19 wave for which the Chinese government had introduced another complete lockdown for some cities (Fortune, 2022). These are just two events of a wide and constantly increasing range of disruptive supply chain events.

A report of EventWatch from 2018 confirms a significant increase in disruption events whether from natural catastrophes (earthquakes, flood, etc.), legal changes (regulations, sanctions), or political events (war, strike) (Burson, 2019). Therefore, current supply chain risk management (SCRM) faces tremendous challenges to cope with these risks and define adequate mitigation strategies to increase supply chain resilience (Christopher & Holweg, 2017). Especially the supply of energy and coping with the scarce resources is one of the major challenges for today’s supply chains. As supply chains are highly connected with a high degree of interfirm relationships also a collaborative risk management approach is required to mitigate these disruptions (Friday et al., 2018; Ivanov, 2021). However, current SCRM approaches still focus on individual firm strategies and lack an overarching view (Munir et al., 2020). Therefore, Li et al. (2015) emphasize the need for a collaboratively end-to-end approach in SCRM. Subsequently, Pettit et al. (2013) have identified collaborative approaches for disruption management as a key success factor for supply chain resilience. Nevertheless, current literature lacks how collaboration relates to supply chain resilience and what factors must be considered to establish a successful collaborative resource sharing (Duong & Chong, 2020).

We aim to contribute to this research gap by answering the research question: “How does collaborative resource sharing enable supply chain disruption management?” The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. Section 4.2 gives an overview of the status in literature regarding the concept of collaborative resource sharing and its influence on supply chain resilience and robustness. We further introduced the concept of the rational view theory, trust, and commitment as a key enabler for collaborative resource sharing. Section 4.3 shows the applied research methodology regarding the survey and further expert interviews. Section 4.4 presents the findings and is followed by a discussion and conclusion in Sect. 4.5.

4.2 Theoretical Background

4.2.1 Supply Chain Resilience and Robustness

As supply chain risks cannot be prevented completely it is also important to react quickly and cost-effectively to disruptions (Melnyk et al., 2010).

Therefore, resilience and robustness are one of the key requirements for supply chain risk management nowadays (Ivanov, 2018). Thereby, supply chain resilience can be defined as the “ability of a system to return to its original state, within an acceptable period of time, after being disturbed” (Christopher & Peck, 2004). Whereas resilience focuses more on reestablishing the baseline situation, robustness as defined by Kitano (2004) is the “ability of the supply chain to maintain its function despite internal or external disruptions.” A robust supply chain is able to withstand risks and maintain its operation (Brandon-Jones et al., 2014).

Thereby, creating resilience and robustness cannot be seen as a one-time event after a disturbance, rather it requires a continuously process (Pettit et al., 2013).

Especially, with the number of increasing disruption events maintaining resilience and robustness becomes more and more important while at the same time also more difficult to achieve. The increasing interlinkages between supply chain partners, reduced inventory levels, logistic concepts such as just in time and just in sequence delivery makes supply chains prone to disruptions with the requirement of a joint answer (Brandon-Jones et al., 2014). Nevertheless, companies still focus on company individual preventive approaches (Marchese & Paramasivam, 2013). However, a collaborative approach based on resource and information sharing among supply chain partners reduce uncertainty and risks significantly (Ivanov 2020).

4.2.2 Collaborative Resource Sharing

A collaborative approach enables the development of synergies among supply chain partners (Whipple & Russell, 2007). This grants the possibility to achieve a higher benefit than the companies would have achieved individually (Cao et al., 2010). Literature provides various examples which confirm the positive impact of supply chain collaboration on performance (Chen et al., 2004). As disruptive events occur network wide the response can also just be from the whole network as well (Christopher & Peck, 2004).

Information exchange, joint planning, and the development of plans to synchronize operations are the basic instruments for collaborative activities (Nyaga et al., 2010). Cao et al. (2010) developed a well-elaborated conceptualization of supply chain collaboration. They define (1) information sharing, (2) goal congruence, (3) decision synchronization, (4) incentive alignment, (5) resource-sharing, (6) collaborative communication, and (7) joint knowledge creation as the basic principles for an effective joint approach to react on disruptions. Thereby, the selection of the best fitting set of resources should be combined by the supply chain partners to create competitive advantages (Bovell, 2012). Ambulkar et al. (2015) define the ability to reconfigure resources as a crucial success factor to achieve supply chain resilience and see collaborative resource sharing as an effective proactive as well as reactive risk management method. Especially trust and commitment are the prerequisite for this and lead to a positive impact (Bode et al., 2011).

The research of Wieland and Wallenburg (2013) confirms the positive correlation of communication and commitment for a collaborative risk management approach. Within the limited range of literature regarding collaborative resource sharing Cao and Zang (2013) emphasized the lack of studies on collaborative resource sharing in supply chain management. A detailed analysis of the necessary capabilities that enables a collaborative resource sharing remains at a silent place in literature (Friday et al., 2018).

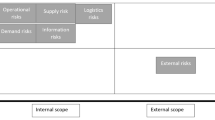

In the cross-sectoral context, Ivanov and Dolgui (2020) and Ivanov (2021) introduced the concept of intertwined supply networks. The key idea of this concept is to utilize the synergetic effects of intersections between supply chains of different industrial sectors (e.g., automotive and healthcare) and to make use of resource-sharing effects.

4.2.3 Relational View Theory

Among the theories used in collaborative resource-sharing literature the most appropriate is the relational view theory showing the significance of relational dimensions (Carey et al., 2011; Brüning & Bendul, 2017). Dyer and Singh (1998) were one of the first who introduced the concept of the relational view theory with a more overarching view instead of a company individual focus. Based on the concept of interlinked networks they state that these inter-firm linkages and interorganizational resources may be a source of relational rents and collaborative performance increase across the entire network. They analyzed four key resources which contribute to relational rents and joint value creation: (1) investment in relational-specific assets, (2) substantial knowledge exchange, (3) combining of complementary, but scarce resources or capabilities, and (4) lower transaction costs than competitor alliances. The available resources within the network represent the complementary resource endowments (Dyer & Singh, 1998). Thereby, companies are able to obtain value from resources that are not fully controlled by their own (Lavie, 2006).

4.2.4 Trust and Commitment

Trust has been researched intensely in the field of supply chain management (Paluri & Mishal, 2020). Thereby, reliability, predictability, and fairness are the three main characteristics of trust (Agarwal & Shankar, 2003). Moorman et al. (1993), define trust as “the willingness to rely on an exchange partner on whom one has confidence, without worrying about the exposure of one’s weakness of vulnerability, and considering the partner as credible, reliable and benevolent, thereby willing to rely on the partner.” Trust implies two involved parties the trustor who is in an uncertain situation and the trustee on whom the trust is placed (Mohammed et al., 2010). Thereby especially uncertainty places a crucial role in the definition of trust. Several researchers confirm the positive impact of trust on supply chain performance (McEvily et al., 2003; Ha et al., 2011).

Although trust and commitment is often used synonymously in practice, researchers have developed various methods to measure it and discuss this in literature separately and define commitment as a result of trust in the supply chain (Paluri & Mishal, 2020). Thereby the involved parties are willing to invest in the partnership and share risks to positively influence supply chain performance (Chen et al., 2011).

4.3 Methodology

In order to answer the research question, an online self-administrated survey was chosen as a data collection method. This method allows for statistical generalization and conclusions are projectable to a larger population (Wieland & Wallenburg, 2012).

The online survey was conducted anonymously during February and March of 2016. The survey was sent to 7861 contacts in supply chain management. To enhance the response rate two reminders were sent out, resulting in a final set of 321 participants which means a response rate of 5.4%. One hundred and five responses had to be excluded due to large incomplete answers, leaving a usable data set of 216 responses.

The questionnaire consists of 48 questions categorized into four sections. Table 4.1 gives an overview of the structure of the questionnaire.

In the introduction section, the research topic and aim of the survey was presented to the participants. Further, some terms such as “time to recover” or “severity” were explained to the participants.

Section A consisted of questions to identify the current status of SCRM in the companies. Participants were asked about their risk management methods, relevance of SC disruptions, and organization of recoveries.

Sections B and C contained the questions relevant to collaborative resource sharing and recovery before and during a supply chain disruption. Therefore, participants were asked to base their answers on a specific SC disruption that they had experienced in the 5 years preceding the data collection. Respondents that had not experienced SC disruptions were questioned about their hypothetical expectations and willingness with regard to collaborative recovery.

The final section D included classification questions regarding industry, company size, etc.

In order to ensure a structured data analysis, the questions were closed questions with predetermined respond categories.

The questionnaire was distributed in a German and English versions. To ensure comprehensibility the questionnaire was tested beforehand with 11 people from academia and industry and their feedback was included in the final survey design.

As Figure 4.1 shows, the majority of the participants are located in the German-speaking area (Germany 76%, Switzerland: 11%, Austria: 3%). International participants were located in France (1%) and the USA (4%). The industries correspond with the most important branches in the German industry landscape (Fig. 4.1).

Also, the company sizes reflect the industrial landscape of the German-speaking area with the majority of small- and medium-sized enterprises (Fig. 4.2).

To test for non-response bias, Chi-square tests were applied to compare early to late respondents’ answers in terms of participant’s experience in company and company size (annual sales and number of employees) (Wagner & Kemmerling, 2010). Based on the result of 0.25 between the two groups across all three analyzed categories the absence of non-response biases is assumed. Further to keep the influence of the common method bias low several measures were considered in the survey design (Guide & Ketokivi, 2015). Thus, confidentially and anonymity of the respondents’ answers was explained in the introduction section to reduce socially desirable responses. The structure of the asked questions was split up into different categories and formulated in a simple and concise way and specific terms were explained. Furthermore, different measurement scales were used.

In addition, eight expert interviews with companies from automotive, aerospace, insurance, and consulting were conducted to discuss the impressions from the survey. The interviews were held in person or via telephone and took between 60 and 90 min and followed a semi-structured approach.

4.4 Findings

The survey showed that 99% of the asked companies already faced a disruption, which confirms that supply chain disruptions cannot be completely eliminated by supply chain risk management. Further, 56.7% stated that this poses a major challenge for their company and still 32.1% rated this a moderate problem. The search and definition of adequate recovery methods is therefore one major challenge for current supply chain risk management. Collaboration is defined as a suitable method to recover from disruptions.

However, our survey showed that the full potential of collaborative resource sharing is still not fully used by the companies.

The major form of collaboration is company internal with subsidiaries or external with different companies such as suppliers, companies from same region or branch or even competitors.

Collaboration within the own company networks requires especially national and international working collaboration. Fifty-three percent of the participants indicated that they already applied internal collaboration as a risk management activity over the past 5 years.

Another form of collaborative recovery is collaboration with other supply chain members. As this requires a close coordination between suppliers, customers, and even sometimes competitors it is less frequently used than internal collaboration. Thirty-five percent of the surveyed companies explained that they used this method as a supply chain risk management activity. Asked with which partner the surveyed companies collaborated most. Eighty-one percent of the companies responded with their first-tier supplier. Almost the same amount of 80% stated that they collaborated with their internal company subsidiaries.

The intensity of collaboration decreases downstream the supply chain. So, 51% responded that they applied a collaboration with their second-tier supplier and 33% with their second-tier customers. Especially with competitors only 25% replied that they had never used a collaborative recovery method. As the underlying reason, they named antitrust.

The intensity of the collaboration shows a similar picture. Based on a scale from 1 (low level) to 7 (high level), the intensity of the collaboration was asked. Thereby the intraorganizational collaboration (5.68) and the collaboration with first-tier suppliers (4.99) were the most intensive forms. Also, collaboration with logistics service providers (4.81) was rated relatively high. They were especially described as a neutral partner in crisis and therefore a favored partner in collaboration activities.

Further companies were asked whether they already shared resources as a method to recover from supply chain disruptions. Thereby production and human resources were investigated separately. Human resources particularly define the sharing of employees whereas production resources comprise machines, warehouse capacities, and factory sharing. Based on a scale of 1 “has never” and 7 “has happened very often,” the survey showed that especially human resources were shared frequently (4.64). Especially due to the high flexibility and mobility of employees they can easily form cross-company teams. Whereas the transferability of production resources is per definition reality low. Table 4.2 shows the rating of the surveyed companies regarding their experiences with human resource and production resource sharing.

Especially trust and commitment were named by the survey participants as one key factor for a successful collaboration which confirms the relational view theory. This is especially the result of a long term oriented trustworthy relationship beforehand. The intensity of collaboration before the disruption significantly influences the level of success and the willingness to also collaborate during a disruption between the supply chain partners. Nevertheless, also the level of dependency influences the willingness to collaborate. Exemplarily, the following example demonstrates this connection. After a fire in a plant in a production site of Philips in Mexico, Nokia as a customer supported during this disruption as they were highly dependent on specific components for the cellphone chip production which they purchased from Philips (Sheffi, 2005).

A close relationship between the supply chain partners becomes especially essential when organizing the collaborative resource sharing. Namely, the survey showed that the majority did not plan the collaboration intensively. Rather fast and flexible commitment was required to collaborate during a disruption. Only 7% agreed upon procedures and defined measures regarding the collaboration form and intensity beforehand. This shows the tremendous potential to integrate collaborative resource sharing as a suitable risk management method and to integrate this in the companies’ risk management activities which are intensively defined, discussed, and regularly updated.

Also, regarding the responsibility of the coordination of the collaboration, there is still potential. Forty-seven percent of the participants stated that only one actor was responsible for the organization of the resource sharing. Asked who was responsible for the organization, 93% of the participants answered that their own company had the main responsibility.

Our survey contains several important findings which we summarize in the following model.

Friday et al. (2018) defined a model of six categories of a higher-order concept which are key factors for successful collaborative risk management. Based on our findings in the survey we elaborated this concept by adding the categories of trust and commitment as well as resource sharing (Fig. 4.3).

Elaborated concept according to Friday et al. (2018)

An effective supply chain risk management should consider these factors for implementing collaborative resource sharing as a standard risk management method. Therefore, we derive first recommendations based on the above-mentioned key success factors on how collaborative resource sharing could be implemented in practice. A collaborative sharing of risk information could be the starting point. Joint web platforms or software solutions offer the possibility to provide and share information between supply chain partners concerning possible impacts on supply chain disruptions such as where in the world happed an earthquake, a fire in a factory and what could be the possible impact on the supply chain, etc. could be monitored (Bendul & Brüning, 2017). Agreed procedures and guidelines following a standardized process could be the basis for all collaborative risk management activities. Especially in chaotic situations which require a fast decision-making which is the case when disruptive events happen, it could be helpful to follow a defined procedure. Therefore, agreed procedures such as responsibilities concerning decisions, information paths, etc. with the most important supply chain partners could be defined to enable fast decisions. This also facilitates joint decision-making cross company wide. Therefore, it would also be helpful that each supply chain partner defines the responsible person who should coordinate the supply chain risk management activities for this company. These responsible persons could form a special task force group that defines and coordinates the collaborative supply chain risk management activities in case of a disruption. Further, a collaborative performance management system could be implemented by the joint definition of relevant key performance indicators such as level of inventory, number of back-up suppliers for fast-moving products, etc. for supply chain risk management. This should be implemented in the company-wide supply chain risk management process of each company and is also the basis for the joint sharing of risks and benefits. Trust and commitment could not be defined by rules and guidelines. This is the result of trustworthy work between the supply chain partners over years. Nevertheless, a framework like a code of conduct where the supply chain partners agree on their most important core values and their commitment to how they want to behave in disruptive situations could be a first step. To facilitate the possible resources which can be shared in case of a disruption it could be helpful that each supply chain partner defines the possible production and human resources. For the production resources, this can be easily summarized in a list of which factories are located where in the world with which machines, tools, etc. Further, this list can be used to make remarks on which of them can be shared and what are the prerequisites for sharing. Exemplarily, a drilling machine could be easily shared, also a punching tool could be transferred between factories whereas special tools such as a laser machine could not be easily transferred. For human resources, it would be helpful that each company defines a short profile of their employees concerning their skills. This facilitates to define the necessary persons depending on the disruptive event as to which resource can be shared.

Table 4.3 summarizes the proposed strategies for practitioners implementing a collaborative supply chain risk management.

4.5 Discussion and Conclusion

The overarching goal of this research was to define how resource sharing enables supply chain disruption management.

The results of our survey confirm the practical relevance of collaborative resource sharing as a risk management method. Due to the increasing occurrence of disruptions which current developments such as the COVID pandemic has shown this need will enhance and companies have to think about collaborative answers to disruptions in order to maintain supply chain resilience (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020; Ivanov, 2021; Ruel et al., 2021). At the same time, it has also been shown that there is a lot of untouched potential regarding the organization and planning of collaborative resource sharing which also Brüning et al. (2015) pointed out in their work. Ivanov (2021b) defined AURA (Active Usage of Resilience Assets) framework to increase supply chain resilience which can be seen as complementary concepts of a successful collaborative supply chain risk management.

Further, our survey demonstrates the sharing of human resources and production resources as a favorable collaboration. This is in line with the findings of the relational view theory of Dyer and Singher (1998) who state that the sharing increases benefits for all involved participants. Especially trust and commitment are central key factors for the willingness to collaborate to share resources. This confirms the growing importance of trust and commitment between supply chin partners described by Paluri and Mishal (2020) and also Cockx et al. (2019).

Our elaborated model regarding the most important categories reading a successful implementation of collaborative risk management makes important theoretical and practical remarks. First, it could serve as a framework for further research in the area of supply chain risk management for researchers. Especially, the relationship between each of the categories could make worthful contributions. Further the influence of environmental factors such as cultural aspects, technological developments etc. offers potential for further research. On the other hand, this framework gives an overview for practitioners about the most relevant factors which should be addressed in the design of collaborative risk management methods. This increases the awareness of the areas which should be covered for the implementation of collaborative resource sharing.

Although, our research makes several contributions some limitations must be considered. First, the participants of the survey mainly come from the german speaking area. Due to the growing interrelationship and globalization, the extension to more international participants would offer further value. Moreover, the research of the eight expert interviews could be extended to a wider set of experts coming from different branches and company sizes.

References

Agarwal, A. & Shankar, R. (2003). On-line trust building in e-enabled supply chain: Supply Chain Management. An International Journal, 8(4), 324–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540310490080

Ambulkar, S., Blackhurst, J., & Grawe, S. (2015). Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. Journal of Operations Management, 33, 111–122.

Bendul, J., & Brüning M. (2017). Collaborative supply chain risk management – new measures for managing severe supply chain disruptions.

Bode, C., Wagner, S. M., Petersen, K. J., & Ellram, L. M. (2011). Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: Insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 833–856.

Bovell, L. J. (2012). Joint resolution of supply chain risks: The role of risk characteristics and problem solving approach. Dissertation, Georgia State University. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/marketing_diss/23

Brandon Jones, B., Squire, C., Autry, K., & Petersen, J. (2014). A contingent resource-based perspective of supply chain resilience and robustness. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 50(3), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12050

Brüning, M., & Bendul, J. (2017). Relational view on collaborative supply chain disruption recoveries. Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL). https://doi.org/10.15480/882.1452

Brüning, M., Hartono, N., & Bendul, J. C. (2015). Collaborative recovery from supply chain disruptions: Characteristics and enablers. Research in Logistics and Production, 3(5), 225–237.

Burnson, P. (2019). https://www.scmr.com/article/global_supply_chain_risk_events_increased_36 _in_2018_according_to_resilincs

Cao, M., Vonderembse, M., Zhang, Q., & Ragu-Nathan, T. S. (2010). Supply chain collaboration: Conceptualization and instrument development. International Journal of Production Research, 48(22), 6613–6635.

Cao, M., & Zhang, Q. (2013). Supply chain collaboration. Springer.

Carey, S., Lawson, B., & Krause, D. R. (2011). Social capital configuration, legal bonds and performance in buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Operations Management, 29(4), 277–288.

Chen, I. J., Paulraj, A., & Lado, A. A. (2004). Strategic purchasing, supply management, and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 22(5), 505–523.

Chen, J. V., Yen, D. C., Rajkumar, T. M., & Tomochko, N. A. (2011). The antecedent factors on trust and commitment in supply chain relationships. Computer Standards and Interface, 33(3), 262–270.

Christopher, M., & Peck, H. (2004). Building the resilient supply chain. International Journal of Logistics Management, 15(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090410700275

Christopher, M., & Holweg, M. (2017). Supply chain 2.0 revisited: a framework for managing volatility-induced risk in the supply chain. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistiks Management 47(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/0.1108/IJPDLM-09-2016-0245

Cockx, R., Armbruster, D., & Bendul, J. C. (2019). Resource sharing as supply chain disruption risk management measure. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 52(13), 802–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2019.11.228

Duong, L. N. K., & Chong, J. (2020). Supply chain collaboration in the presence of disruptions: A literature review. International Journal of Production Research, 58(11), 3488–3507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1712491

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 660–679.

Fortune. (2022). https://fortune.com/2022/03/14/china-shenzhen-lockdown-covid-foxconn-apple-supply-chain/

Friday, D., Ryan, S., Sridharan, R., & Collins, D. (2018). Collaborative risk management: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 48(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2017-0035

Guide, D., & Ketokivi, M. (2015). Notes from the Editors: Redefining some methodological criteria for the journal. Journal of Operations Management, 37, v–viii.

Ha, B. C., Park, Y. K., & Cho, S. (2011). Suppliers’ affective trust and trust in competency in buyers: Its effect on collaboration and logistics efficiency. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 31(1), 56–77.

Ivanov, D. (2018). Structural dynamics and resilience in supply chain risk management. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-69304-0.

Ivanov, D. (2020). ‘A Blessing in Disguise’ or ‘as if it Wasn’t Hard Enough Already’: Reciprocal and aggravate vulnerabilities in the supply chain. International Journal of Production Research, 58(11), 3252–3262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2019.1634850

Ivanov, D. (2021a). Supply chain viability and the COVID-19 pandemic: A conceptual and formal generalisation of four major adaptation strategies. International Journal of Production Research, 59(12), 3535–3552.

Ivanov, D. (2021b). Lean resilience: AURA (Active Usage of Resilience Assets) framework for post-COVID-19 supply chain management. International Journal of Logistics Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2020-0448

Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2020). Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Production Research, 58(10), 2904–2915.

Kitano, H. (2004). Biological robustness. Nature Reviews Genetics, 5(11), 826–837. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1471

Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638–658.

Li, G., Fan, H., Lee, P. K. C., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2015). Joint supply chain risk management: An agency and collaboration perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 164, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.02.021

Marchese, K., & Paramasivam, S. (2013). Deloitte: The Ripple Effect: How manufacturing and retail executives view the growing challenge of supply chain risk.

McEvily, B., Perrone, V., & Zaheer, A. (2003). Trust as an organizing principle. Organization Science, 14, 91–103.

Melnyk, S. A., Davis, E. W., Spekman, R. E., & Sandor, J. (2010). Outcome-driven SCs. MIT Sloan Management Review, 51(2), 33–33.

Mohammed, L., Sahay, B., Sahay, V., & Abdul, W. (2010). Measuring trust in supply chain partners’ relationships. Measuring Business Excellence, 14(3), 53–69.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81–101.

Munir, M., et al. (2020). “Supply chain risk management and operational performance: The enabling role of supply chain integration.” International Journal of Production Economics 227.

Nyaga, G. N., Whipple, J. M., & Lynch, D. F. (2010). Examining supply chain relationships: Do buyer and supplier perspectives on collaborative relationships differ? Journal of Operations Management, 28(2), 101–114.

Paluri, R. A., & Mishal, A. V. (2020). Trust and commitment in supply chain management: A systematic review of literature. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27, 2831–2862.

Pettit, T. J., Croxton, K. L., & Fiksel, J. (2013). Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development and Implementation of an Assessment Tool. Journal of Business Logistics, 34(1), 46–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12009

Piller, T. (2022). https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/unternehmen/bei-volkswagen-stehen-zwei-werke-still-17838335.html

Ruel, S., El Baz, J., Ivanov, D., & Das, A. (2021). Supply chain viability: Conceptualization, measurement, and nomological validation. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-03974-9

Sheffi, Y. (2005). The resilient enterprise: Overcoming vulnerability for competitive advantage. MIT Press.

Wagner, S. M., & Kemmerling, R. (2010). Handling nonresponse in logistics research. Journal of Business Logistics, 31(2), 357–381.

Whipple, J. M., & Russell, D. (2007). Building supply chain collaboration: A typology of collaborative approaches. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 18(2), 174–196.P\hspace*{-2pt}

Wieland, A., & Wallenburg, C. M. (2012). Dealing with supply chain risks: Linking risk management practices and strategies to performance. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 42(10), 887–905.

Wieland, A., & Wallenburg, C. M. (2013). The influence of relational competencies on supply chain resilience: A relational view. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 43, 300–320.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kessler, M., Arlinghaus, J.C. (2022). Managing Supply Chain Disruption by Collaborative Resource Sharing. In: Dolgui, A., Ivanov, D., Sokolov, B. (eds) Supply Network Dynamics and Control. Springer Series in Supply Chain Management, vol 20. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09179-7_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09179-7_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-09178-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-09179-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)