Abstract

This study proposed a research model to examine the relationship between service quality, zakat payers’ satisfaction, and zakat payers’ trust in a particular zakat institution. Questionnaires were completed by 553 zakat payers who had experience paying zakat either through the institution or its proxies. Data were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The findings reveal relationships between service quality and zakat payers’ trust, service quality and zakat payers’ satisfaction, and zakat payers’ satisfaction and zakat payers’ trust. Zakat payers’ satisfaction was revealed as a mediator in the relationship between service quality and zakat payers’ trust. Therefore, zakat institutions must focus on service quality to increase zakat payers’ satisfaction and trust. Implications are discussed concerning service quality management in the zakat sector.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Self-distribution zakat payment has increased from year to year in Malaysia. Even though specific laws prohibit the self-distribution practice, the act continues to grow because zakat payers believe that the zakat payment should reach the zakat recipients regardless of which channels they have to do. Information technology is accelerating the zakat industry revolution. To secure zakat payers’ compliance behavior, zakat institutions need to gain trust from zakat payers. Therefore, zakat institutions need to provide quality service to ensure zakat payers’ satisfaction and trust. Many researchers have found that better customer service leads customers to commit to service providers (Cho and Hu 2009). In zakat, good quality of service is crucial to increase zakat compliance in zakat payers.

Zakat compliance behavior is the key to zakat institutions’ sustainability to secure the optimum amount of zakat collections. Zakat compliance behavior reduces leakage in zakat collection and increases zakat payment (Mokhtar et al. 2018). To ensure zakat payers’ satisfaction and zakat payers’ trust, zakat institutions must focus on service quality. In a world with revolution information technology, the focus should be both traditional and electronic service quality. Zeithaml et al (2000) developed e-SERVQUAL as an updated version of the traditional SERVQUAL model to measure electronic service quality in the Internet setting. The multi-item scale has seven dimensions: efficiency, reliability, fulfillment, privacy, responsiveness, compensation, and contact. Zeithaml et al. (2002) defined e-service as efficiency and effectiveness purchased by customers of electronic services. However, e-SERVQUAL did not thoroughly analyze customer satisfaction, customer trust, and customer loyalty compared to measurement scales developed by Chu et al. (2012). Their study examined the link between e-service quality, customer satisfaction, customer trust, and loyalty in the context of e-banking in Taiwan (Chu et al. 2012).

However, this study studied service quality focused on both traditional and electronic service quality. The relationship of service quality with zakat payers’ satisfaction and zakat payers’ trust will be examined. This study attempts to fill the gaps left by previous researchers who focused on developing scales to measure traditional service quality instead of relationships with other constructs (Ghani et al. 2012; Wahab et al. 2016). This study also highlights the mediating effect of zakat payers’ satisfaction on the relationship between service quality and zakat payers’ trust.

The residue of this paper is structured as follows. The succeeding section reviews the related literature on service quality, customer satisfaction, and trust. The following section presents the research methodology. The subsequent section outlines the results. The final section concludes this study.

2 Service Quality and Zakat Payers’ Satisfaction in Zakat Payers’ Trust Model

Many studies have been conducted on service quality in the zakat context. For example, (Ghani et al. 2012) in their study developed an instrument, namely INOPERF (Islamic Non-profit Organization Per Formance), to measure service quality performance. This instrument, which was based on the Carter instrument, was deemed fit to measure the service quality of zakat institutions. Wahab et al. (2016) later used the developed instrument to examine the impact of service quality on customer satisfaction against the five dimensions of reliability, tangible, empathy, responsiveness, and compliance. Some studies used service quality as a determinant in their research models (Zainal et al. 2016; Noor and Saad 2016).

However, previous studies mainly focused on traditional service quality. In other words, the previous scales and instruments mainly catered to the evaluation of service quality over the counters. Service quality should be examined and evaluated broader than traditional service quality since zakat payers can now pay zakat payment through many channels. Some prefer to pay through the counters and representatives, and some choose to make payment through the e-zakat payment. Therefore, if service quality should be appraised, the appraisal must cover both traditional and electronic channels.

In the pre-covid19 era, where the traditional channel was preferred, more zakat payers are encouraged to make online payments after the shocking pandemic. The pandemic caused more zakat payers to be adept at paying zakat through online payment and shifted from the traditional channel as they found it more convenient (COVID-19: Bayar zakat fitrah dalam talian 2020). Due to this new transition, a new way to measure service quality must be found. Regardless, it involves traditional or electronic service quality; service quality is crucial for a successful method to gain zakat compliance behavior that cannot be debunked (Saad et al. 2019). Rasheed and Abadi (2014) found that improving service quality increases more loyal customers.

Trust comprises beliefs about an exchange partner's benevolence, competence, honesty, and predictability and is an essential element of successful relationships (Moorman et al. 1992, 1993). In the context of zakat, trust is a series of beliefs regarding the attributes that zakat payers may or may not trust a zakat institution to exhibit.

Trust is gained from customers when satisfied with the service providers in traditional business environments if they observe those service providers fulfill specific requirements they set for those service providers (Parasuraman et al. 1988). However, from the perspective of online environments, there are fewer tangible aspects. The focus of requirements from customers mainly revolves around service attributes such as the reliability of the information, availability of the website, and efficiency of transaction execution (Chu et al. 2012). In short, the difficulty of setting pre-consumption expectations of service quality in online environments makes the customers trust the service provider through their experience (Zeithaml 2000). As a result, in this study, the evaluation for service quality is simplified to fit both traditional and electronic environments, thus creating a relatively simple scale for measuring service quality.

Chang et al. (2013) in their study revealed that service quality positively influenced patients’ trust since their study involved the relationship between hospitals (service providers) and patients (service recipients). Cho and Hu (2009) their earlier studies that focused on a financial institution found that service quality significantly affected customer trust. Service quality is well established as a determinant of customer satisfaction in numerous studies (Janahi and Mubarak 2017; Casidy 2014). Wahab et al. (2016) found that improving service quality increased more satisfied customers.

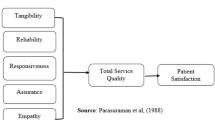

Customer satisfaction is defined as customers’ evaluation based on the difference between their pre-purchase expectation and post-purchase experience (Kotler and Armstrong 1999; Oliver 1981). Customers are usually satisfied if the post-purchase experience exceeds their pre-purchase expectations. In the context of zakat payers, zakat payers’ satisfaction is defined as a good feeling that zakat payers have when they hope that zakat institutions do something on behalf of their payment. The institutions do perform the deeds and fulfill their expectations. However, a lack of recently reported studies proved customer satisfaction was a determinant of trust. However, Chu et al. (2012) did find a positive and direct link between customer satisfaction and customer trust in their study on e-banks in Taiwan. Previous studies focused on trust as a mediator in the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction (Kundu and Datta 2015) and trust as the antecedent of customer loyalty (Trif 2013; Suki 2011). This study intends to enrich the literature on zakat payers’ satisfaction as an antecedent of trust and a mediator in the relationship between service quality and zakat payers’ trust. Based on the preceding literature review, the causality model in this study was proposed, as shown in Fig. 1.

3 Methodology

3.1 Measures

Multi-item scales derived from previous research were used to measure the study variables, with all items rated on 6-point Likert-type scales (1 = completely disagree, 6 = completely agree). The empirical data gained in this study were drawn from zakat payers of 10 districts in Kelantan, Malaysia, and PLS-SEM was used as the primary analysis tool.

A PLS model is usually analyzed and interpreted in two stages (Hulland 1999). The first stage involves the validity and reliability analyses to measure the model. In this stage, every measure in the model is tested. In the second stage, the paths between the constructs in the model are estimated to test the structural model. The predictive ability of the model is also being determined at this stage. These stages must be done subsequently to make sure the model uses the reliable and valid measures of the constructs before concluding the nature of the construct relationships.

3.2 Sample and Procedure

1000 questionnaires were dispatched to individual zakat payers with experience dealing with a zakat institution and its proxies in Kelantan. There were 553 valid responses obtained. A description of the responses broken down by demographics can be found in Table 1.

4 Results

PLS was used in this study to perform the analysis of the research model depicted in Fig. 1. The outputs from the PLS software were used first to test the measurement model and then test the fit and performance of the structural model. PLS structural equation modeling was applied to test the relationships among the constructs (Fornell and Cha 1994). Specifically, the employment of SMARTPLS allows for simultaneous testing of hypotheses (Ringle et al. 2005), multi-item measurement, the use of both reflective and formative scales (Fornell and Bookstein 1982), and is capable of doing additional analysis for mediation and moderating effect (Basbeth and Ibrahim 2018). Results for SMARTPLS are shown in Table 2, Table 3, and Fig. 2.

Reliability was measured using the internal consistency index (Fornell and Larcker 1981), with a measure that will be considered reliable if the index reached at least 0.70 (Nunally 1978). The reliability result is as reported in Table 2. Convergent validity was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE), standard output from SMARTPLS. Measures with an AVE of 0.50 or higher exhibit convergent validity (Chin 1998). The AVEs reported in Table 2 all exceed 0.60, confirming that all measures demonstrated satisfactory convergent validity.

Discriminant validity is established using the latent variable correlation matrix, which has the square root of AVE for the measures on the diagonal, and the correlations among the measures as the off-diagonal elements (see Table 3). The matrix must be constructed from the PLS output. Discriminant validity is determined by looking down the columns and across the rows and is deemed satisfactory if the diagonal elements are larger than off-diagonal elements. Discriminant validity was demonstrated for our model, as these conditions are satisfied (see Table 3). R2 values indicate the predictive ability of the independent variables. Zakat payers’ satisfaction and zakat payers’ trust with R2 values of 0.414 and 0.520, respectively, are considered to provide adequate evidence of the model’s predictive ability (shown in Fig. 2). Additionally, path coefficients are reported in Fig. 2.

5 Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the link between service quality and zakat payers’ trust and establish whether or not the latent variable of zakat payers’ satisfaction influences this link. The zakat payers in this study were predominantly male and between 31 to 40 years of age. As with any service quality, it is known as a determinant of customer satisfaction (Chu et al. 2012). With the increased technology-centric and information-based era, the need to study service quality from both physical and virtual angles becomes significantly essential (Lee et al. 2011). Given that service quality attributes can potentially affect zakat payers’ attitudes toward a zakat institution, pursuing service quality during physical and virtual payment, enhancing zakat payers’ satisfaction and zakat payers’ trust are good suggestions. To this end, we have proposed a research framework supported by the PLS structural equation modeling. Given the findings gained in this study, it appears that we were able to establish a direct link between service quality and zakat payers’ satisfaction, between service quality and zakat payers’ satisfaction, and between zakat payers’ satisfaction and trust. In addition, it was found that zakat payers’ satisfaction was indeed a mediator in the relationship between service quality and zakat payers’ trust. In other words, a zakat institution must gain trust from its zakat payers by providing excellent service quality physically and virtually. Excellent physical and virtual service quality impacts the zakat payers’ satisfaction and gains their trust.

The relationship between zakat institutions and zakat payers is the key to sustaining the institutions as the bridge between zakat payers and zakat recipients. Trust, in this case, is a competitive advantage. The development of a global logistics system and the awareness of social distancing increase the zakat collection by the zakat institutions if they increase Internet technologies with information applications. This study proves that service quality and zakat payers’ satisfaction positively influence zakat payers’ trust. Therefore, the institutions can use relationship marketing to foster zakat payers’ trust, increase their medium of interaction with zakat payers and aim for compliance (Cho and Hu 2009). The compliance from zakat payers can reduce the self-distribution of zakat payment. In the long term, old zakat payers can be retained, and new zakat payers will be attracted. The institutions can successfully reduce the leakage in zakat collection.

The findings from this study provide several implications for service quality management generally and service specifically. To establish good relationships with their zakat payers, zakat institutions must enhance their service quality through physical and e-zakat payment. In this way, they can obtain the satisfaction and trust of zakat payers. Future researchers could investigate whether poor service quality leads to reducing zakat payers' satisfaction.

The results gained in this research must be considered in the light of limitations related to the sample and measures utilized. This study is generalizable only in the Kelantan state context. These limitations can be overcome in future studies by using samples from all the states in Malaysia.

In conclusion, this research provides theoretical and practical contributions to the literature on zakat payers’ trust. From the theoretical perspective, this proposed model includes measures from Chu et al. (2012), which fit to accommodate the nature of zakat payers who paid zakat via counters and online channels. The measures also deviated from the measures of service quality developed by Wahab et al. (2016), which was more specialized for a zakat institution. From a practical perspective, the findings in this study provide insights for zakat institutions and zakat payers. The findings guide zakat institutions to focus on zakat payers’ segmentation and other marketing initiatives to increase zakat collection.

Thus, further studies may reflect other dimensions in exploring the issue of zakat payers’ trust. Furthermore, future research should outspread the findings to a large sample in each state to increase the generalizability of the results derived in the current study. Another potential in the research framework is to explore the effect of zakat payers' trust on zakat compliance behavior in future studies.

References

Basbeth, F., Ibrahim, M.A.H.: Four Hours Basic PLS-SEM: A Step by Step Guide with Video Clips. iPRO Publication, Selangor, Malaysia (2018)

Casidy, R.: Linking brand orientation with service quality, satisfaction, and positive word-of-mouth: evidence from the higher education sector. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 26(2), 142–161 (2014)

Chang, C.-S., Chen, S.-Y., Lan, Y.-T.: Service quality, trust, and patient satisfaction in interpersonal-based medical service encounters. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13(22), 1–11 (2013)

Chin, W.: The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. Modern Method for Business Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ (1998)

Cho, J.E., Hu, H.: The effect of service quality on trust and commitment varying across generations. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 33, 468–476 (2009)

Chu, P.-Y., Lee, G.-Y., Chao, Y.: Service quality, customer satisfaction, customer trust, and loyalty in an e-banking context. Soc. Behav. Pers. 40(8), 1271–1284 (2012)

COVID-19: Bayar zakat fitrah dalam talian (22 April 2020). BHonline. https://www.bharian.com.my. Accessed 18 Jan 2020

Fida, B.A., Ahmed, U., Al-Balushi, Y., Singh, D.: Impact of service quality on customer loyalty and customer satisfaction in Islamic banks in the Sultanate of Oman. SAGE Open 10(2), 1–10 (2020)

Fornell, C., Bookstein, F.L.: Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 19, 440–452 (1982)

Fornell, C., Cha, J.: Partial Least Squares in Advanced Methods of Marketing Research. Blackwell, Cambridge, MA (1994)

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F.: Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981)

Ghani, E.K., Said, J., Yusuf, S.N.S.: Service quality performance measurement tool in Islamic non-profit organisation: an urgent need. Int. Bus. Manag. 5(2), 71–75 (2012)

Hulland, J.: Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 20, 195–204 (1999)

Janahi, M.A., Mubarak, M.M.S.A.: The impact of customer service quality on customer satisfaction in Islamic banking. J. Islam. Market. 8(4), 595–604 (2017)

Kotler, P., Armstrong, G.: Principles of Marketing (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ (1999)

Kundu, S., Datta, S.K.: Impact of trust on the relationship of e-service quality and customer satisfaction. EuroMed J. Bus. 10(1), 21–46 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-10-2013-0053

Lee, G.Y., Chu, P.Y., Chao, Y.: Service quality, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in Taiwanese Internet banks. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 39, 1127–1140 (2011)

Mokhtar, S.S.S., Mahomed, A.S.B., Hashim, H.: The factors associated with zakat compliance behaviour among employees. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 12(S2), 687–696 (2018)

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., Deshpande, R.: Relationships between providers and users of market research. J. Mark. Res. 29(2), 82–104 (1992)

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., Zaltman, G.: Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Market. 57, 81–101 (1993)

Noor, A.M., Saad, R.A.J.: The mediating effect of trust on the relationship between attitude and perceived service quality towards compliance behavior of zakah. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 6(S7), 27–31 (2016)

Nunally, J.C.: Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill, New York (1978)

Oliver, R.L.: Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction process in retail setting. J. Retail. 57(3), 18–48 (1981)

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L.: SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 64, 12–40 (1988)

Rasheed, F.A., Abadi, M.F.: Impact of service quality, trust and perceived value on customer loyalty in Malaysia services industries. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 164, 298–304 (2014)

Ringle, C., Wende, S., Will, A.: SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta. University of Hamburg, Hamburg (2005)

Saad, R.A.J., Farouk, A.U., Wahab, M.S.A., Ismail, M.: What influence entrepreneur to pay Islamic tax (zakat)? Acad. Entrep. J. 25(Special Issue 1), 1–13 (2019)

Sawmar, A.A., Mohammed, M.O.: Enhancing zakat compliance through good governance: a conceptual framework. ISRA Int. J. Islam. Finan. 13(1), 136–154 (2021)

Suki, N.M.: A structural model of customer satisfaction and trust in vendors involved in mobile commerce. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. (IJBSAM) 6(2), 18–30 (2011)

Trif, S.-M.: The influence of overall satisfaction and trust on customer loyalty. Manag. Market. 8(1), 109–128 (2013)

Wahab, N.A., Ibrahim, A.Z., Zainol, Z., Bakar, M.A., Minhaj, N.: The impact of service quality on zakat stakeholders satisfaction: a study on Malaysian zakat institutions. JMFIR 13(2), 71–91 (2016)

Zainal, H., Bakar, A.A., Saad, R.A.J.: The role of reputation, satisfactions of zakat distribution, and service quality in developing stakeholder trust in zakat institutions. In: The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, pp. 524–530 (2016)

Zeithaml, V.A.: Service quality, profitability, and the economic worth of customers: what we know and what we need to learn. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 28, 67–85 (2000)

Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A., Malhotra, A.: Service quality delivery through web sites: a critical review of extant knowledge. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 30, 362–375 (2002)

Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A., Malhotra, A.: E-service Wuality: Definition, Dimensions and Conceptual Model. Cambridge, MA (2000)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Nawi, R.M., Said, N.M., Hasan, H. (2023). Zakat Payers’ Satisfaction as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Service Quality and Zakat Payers’ Trust. In: Alareeni, B., Hamdan, A. (eds) Sustainable Finance, Digitalization and the Role of Technology. ICBT 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 487. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08084-5_65

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08084-5_65

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-08083-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-08084-5

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)