Abstract

The pandemic is changing future trends in retailing and ecommerce immense. Recent research revealed a considerable increase in the use of online grocery shopping (OGS). However, less is known about whether consumers’ behavior is evolving to a ‘new normal’ or returning to ‘old habits’ after pandemic restrictions. To close this research gap, we operationalize and empirically analyze different purchase patterns of consumers in between offline and online channels before, during, and after lockdown restrictions in Germany. The findings show that some consumers refrained from brick-and-mortar retail during the lockdown, but returned after pandemic restrictions. They have lost virtually no consumers entirely to OGS. Therefore, the observed consumers are still in the range of offline retailers. Because of this, offline retailers should act now to retain their consumers, e.g. by offering competitive benefits in their stores or by adding an online channel. Our findings on OGS show much more differentiated purchase patterns. Some consumers start using OGS before or during lockdown, others quit using it. OGS providers should urgently analyze the churn of their customers and derive measures for customer retention. The fact that a total of 93% of the observed consumers do not practice OGS shows that OGS is still in its infancy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The pandemic has changed the world of retailing dramatically over a short period of time (Roggeveen und Sethuraman 2020). On the one hand, these changes pose immense challenges for brand managers and retailers. On the other hand, it also provides new opportunities for retailing and ecommerce (OECD 2022). For instance, consumers’ habits have been severely restricted extrinsically, especially by lockdowns. Brick-and-mortar retail was limited to the most necessary during this period. While grocery stores had predominantly stayed open, other retail sectors did not. The resulting decline in sales and even insolvencies of entire businesses will change whole business sectors (DW: COVID 2021a, 2021b; pwc 2022). These transformations will, in turn, also affect the future of grocery shopping, e.g. in increasing opportunities to buy groceries online (Mortimer et al. 2016; Driediger and Bhatiasevi 2019; Alaimo et al. 2020). While the consequences of the pandemic are dramatically and existentially challenging, it also creates scope for new practices and emerging business models. Roggeveen and Sethuraman (2020) suggest that online grocery shopping (OGS) will increase as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, they expect changes in consumer behavior in the future. Figure 1 supports this view, as it shows a substantial increase in OGS during the pandemic.

OGS and the pandemic offer new opportunities to gain competitive advantage (McKinsey and Company 2022). However, companies need to know how to act on these developments. Despite this high relevance, there is still a lack of research in analyzing different consumers’ purchase patterns before, during and after the pandemic restrictions. In particular, understanding the impact of pandemic restrictions (e.g., lockdown) on consumer buying behavior is important to help brand managers and retailers rapidly respond to these immense changes. In fact, “ignoring trends can give rivals the opportunity to transform the industry” (Harvard Business Review 2010).

Numerous studies have already confirmed the increase in the use of OGS during the pandemic worldwide (Bauerová and Zapletalová 2020; Grashuis et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Pantano et al. 2020; Al-Hawari et al. 2021; Baarsma and Groenewegen 2021; Chang and Meyerhoefer 2021; Ellison et al. 2021; Guthrie et al. 2021; Habib and Hamadneh 2021; Jensen et al. 2021). Additionally, Brüggemann and Pauwels (2022) found significant differences between also-online and offline-only grocery shoppers in both their attitudes and purchasing behavior. However, it has not yet been explored how offline and online grocery purchases are affected by pandemic restrictions. Moreover, there is a lack of research on whether a ‘new normal’ will emerge or whether consumers will return to ‘old habits’.

For instance, consumers who were already familiar with OGS before the pandemic may also shop online during and after the pandemic. However, it is also conceivable that consumers who previously purchased offline-only might also shop online during the pandemic restrictions, but return to their old habits afterwards. On the other hand, they could continue to purchase online after the pandemic restrictions, at least to some extent.

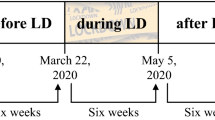

This paper provides insights on how consumers behave before, during and after the pandemic restrictions regarding OGS. For this purpose, we use household panel data from 2019–2020. We observe offline and online purchases before, during, and after the first lockdown of the pandemic in Germany from March 22 to May 05. This allows us to analyze changes in offline and online purchases of 25,038 households. To do this, we systematically operationalize several purchase patterns of the reporting households. We then assigned the observed households to these purchase patterns. This approach provides for the first time sophisticated insights into how consumers’ offline and online grocery shopping behavior evolved before, during, and after the pandemic restrictions. With this study, we answer the following research question:

How does consumer purchase behavior evolve during and after the pandemic restrictions in terms of online and offline grocery shopping?

2 Data and Empirical Analysis

2.1 Data and Purchase Patterns

We use household panel data from 2019–2020 provided by Growth from Knowledge (GfK).Footnote 1 The data includes purchases from the product groups chocolate bars, coffee, hair shampoo, and laundry detergent from around 30,000 households on average. Additionally, it is also determined whether the purchases were made offline or online. The purchase data are analyzed under consideration of the first lockdown in Germany from March 22 to May 5. Only households that purchased both before and after this lockdown are included in the analysis. This way, we ensure that only continuously purchasing households are analyzed. Thus, we observe 25,038 continuous reporting households. For both offline and online purchases, we derive eight behavioral patterns to observe consumers’ purchase behavior before, during and after the lockdown. To identify the different purchase patterns, we code them by attributing to each household a 0 for no purchases and a 1 for purchases in each observation period (before, during, and after lockdown). For instance, a coding of 1-0-0 means that the related household only purchased before the lockdown and neither during nor after.

2.2 Empirical Results

The offline purchase patterns before, during and after the lockdown are shown in Table 1. Based on these purchase patterns, different household types are specified (see second column).

The majority of consumers purchased offline before, during and after the lockdown (81.43%; 20,382). During the lockdown, 18.37% (4,597) did not purchase offline. The fact that these consumers return to brick-and-mortar retail after the lockdown shows that they (at least partially) return to their old habits and do not completely change their behavior to OGS.

Table 2 shows the results regarding the online purchase patterns. Here, the empirical results show a more differentiated behavior than in offline purchasing behavior.

Among the (also-)online purchasing households, 33.74% (574) purchased online only before the lockdown. In other words, more than one-third of these households have not shopped online since the first lockdown. Exclusively during the lockdown, only 6.94% (118) of (also-)online grocery shoppers purchased online. Thus, the lockdown seems to have been a reason for only a few consumers to start using OGS. In contrast, after the lockdown, 29.75% (506) of (also-)online grocery shoppers chose OGS for the first time. On the one hand, this suggests that a lockdown does not greatly increase online shopping households. On the other hand, there still is a substantial amount of fluctuation among OGS. Some consumers try out OGS, but then purchased offline-only again. Other consumers started OGS during or after pandemic restriction. Other consumers purchased (also-)online before and after the lockdown, but not during (15.29%; 260). In addition, the results show that few of the (also-)online shoppers started using OGS since the lockdown (4.29%; 73) or stopped using OGS since the lockdown (1.94%; 33). Only 8.05% (137) of the observed households purchased groceries online before, during, and after the lockdown. In comparison with offline purchases, the (also-)online purchasing households represent 6.79% (1,701). Overall, our results of the online grocery purchase patterns show strong dynamics in the use of the OGS.

3 Implications

The results of this study clearly show different purchase patterns between offline and online purchases. With a view to the offline purchase patterns, we found that almost all of the observed consumers purchase groceries from brick-and-mortar retailers after the lockdown (99.81%; 24.990)Footnote 2. It is particularly relevant for brick-and-mortar retailers that 18.37% (4,597) of consumers abstained from brick-and-mortar retail during the lockdown, but came back to buy groceries offline afterwards. This result shows that offline grocery shopping is mainly affected by a lockdown in the short term. Thus, consumers are still in the reach of brick-and-mortar retailers. Nevertheless, there is a risk that brick-and-mortar retailers will increasingly lose market share to online grocery retailers (see Fig. 1). Brick-and-mortar retailers should focus on generating and communicating competitive advantages over online providers (e.g., via price, experience or service), as long as this is feasible for them. For instance, consumers can haptically experience the products in brick-and-mortar retail, which is hardly possible in online stores (De Canio and Fuentes-Blasco 2021).

After all, if retailers lose consumers to online grocery retailers, influencing and winning back these consumers will be much more challenging. Brick-and-mortar retailers should also think about adding an online channel in order to reduce their disadvantages compared with online providers (e.g., shopping at any time and anywhere as well as home delivery).

Compared to the offline purchase patterns, we found considerably more divergent online purchase patterns. Since 42.62% (725)Footnote 3 of (also-)online purchasing consumers bought groceries online before or during the lockdown but not afterwards, OGS providers should critically evaluate their customer retention measures. OGS providers need to identify these consumers as well as possible reasons for their suspended OGS use.

However, these consumers are also contrasted with new consumers who have started using OGS. For instance, 34.04% (579)Footnote 4 of (also-)online grocery shoppers began shopping for groceries online during or after the lockdown. This high fluctuation brings both threats and opportunities for brand managers as well as for retailers. For instance, there is a risk that actual customers will either switch to competitive online suppliers or satisfy their needs in brick-and-mortar stores (again). However, the high dynamics of OGS can also persuade new consumers to shop for groceries online. The fact that more than 93% of households purchased offline-only during the entire observation period shows that OGS is not yet very widespread. On the other hand, it shows the immense untapped potential.

4 Conclusion

This study contributes to a better understanding of how consumer purchasing behavior evolves during and after the pandemic restrictions on online and offline grocery shopping. During the first lockdown in Germany, almost one in five consumers avoided brick-and-mortar stores. The offline purchase patterns are characterized by ‘old habits’, because after the lockdown almost all of the observed consumers visit the brick-and-mortar retail again. Thus, consumers did not completely switch from offline to online channel as a result of pandemic restrictions. For brick-and-mortar retailers, the results provide valuable insight that it is still possible to influence customers in their own stores, since almost all of the consumers observed still shop (also-)offline. Brick-and-mortar retailers must now develop strategies to retain their customers in the long term. Either through competitive advantages over online retail (e.g., via price, experience or service) or by adding an online distribution channel. If consumers are accustomed to online channels and increasingly purchase their groceries online, it will become much more challenging for brick-and-mortar retailers to reach out to these consumers. Fundamentally, it is key for these companies to anticipate and act on these game-changing trends to shape new standards and be successful in the long term (Harvard Business Review 2010). Otherwise the return to ‘old habits’ in offline purchasing behavior seen here will become a ‘new normal’ in the sense of an increasing migration of customers to online stores.

Our findings on OGS show an ongoing process of change due to a high level of dynamism in online purchase patterns. During the observation period, the buying behavior of (also-) online purchasing consumers changes in different ways. Some consumers started OGS before or during the lockdown, but then switched back to shopping at brick-and-mortar stores only again. Other consumers started OGS before or during the lockdown and maintained this shopping behavior afterwards. These findings indicate a ‘new normal’ – at least for certain consumer segments.

In conclusion, this study provides insight into the consumer purchasing behavior both offline and online before, during, and after pandemic restrictions. In particular, brand managers and retailers should take this analysis as an opportunity to consider changes in consumers’ behavior in more detail in order to derive measures to increase loyalty. Additionally, these new insights provide a deeper knowledge of consumer purchasing behavior. Thus, they can derive specific marketing strategies to face future challenges in retailing and e-commerce.

However, this research has some limitations. It cannot be clearly proven that the changes in the purchasing behavior of offline and online purchase patterns are caused by the pandemic. The processes of change in consumer purchasing behavior may be also driven (at least in part) by digitization, increasing online offers, and changing demands. Furthermore, we cannot draw any conclusions about a quantitative shift in demand between offline and online purchases. For instance, it is obvious that consumers who use OGS regularly are purchasing a higher quantity and thus are more relevant for OGS providers online.

While this study specifically analyzes consumer behavior regarding offline and online purchases, further research can additionally consider the quantity sold per household. Additionally, it should be clarified whether consumers with different purchase patterns actually differ, e.g. in terms of consumer characteristics and demographics, organic and fair trade products, price consciousness or national brand preference. Further research can be focused on a combined consideration of offline and online purchase patterns. In this way, purchase patterns could be generated to simultaneously reflect the changes in consumers’ buying behavior both online and offline.

Notes

- 1.

The source of the data is GfK Consumer Panels & Services.

- 2.

Considered purchase patterns: ‘offline 0-0-1’, ‘offline 1-0-1’, ‘offline 0-1-1’, and ‘offline 1-1-1’.

- 3.

Considered purchase patterns: ‘online 1-0-0’, ‘online 0-1-0’ and ‘online 1-1-0’.

- 4.

Considered purchase patterns: ‘online 0-0-1’, ‘and online 0-1-1’.

References

Alaimo, L.S., Fiore, M., Galati, A.: How the COVID-19 pandemic is changing online food shopping human behaviour in Italy. Sustainability 12(22), 9594 (2020)

Al-Hawari, A.R.R.S., Balasa, A.P., Slimi, Z.: COVID-19 impact on online purchasing behaviour in Oman and the future of online groceries. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 6(4), 74–83 (2021)

Bauerová, R., Zapletalová, Š.: Customers’ shopping behaviour in OGS – changes caused by COVID-19. In: 16th Annual International Bata Conference for Ph. D. Students and Young Researchers, p. 34 (2020)

Baarsma, B., Groenewegen, J.: COVID-19 and the demand for online grocery shopping: empirical evidence from the Netherlands. De Economist 169, 407–421 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-021-09389-y

Brüggemann, P., Pauwels, K.: Consumers’ attitudes and purchases in online versus offline grocery shopping. In: Martinez-Lopez, F.J., Gázquez-Abad, J.C., Ieva, M. (eds.). Advances in National Brand and Private Label Marketing NB&PL 2022, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economoics. Springer, Cham (2022)

Chang, H.H., Meyerhoefer, C.D.: COVID-19 and the demand for online food shopping services: empirical evidence from Taiwan. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 103(2), 448–465 (2021)

De Canio, F., Fuentes-Blasco, M.: I need to touch it to buy it! How haptic information influences consumer shopping behavior across channels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 61, 102569 (2021)

Driediger, F., Bhatiasevi, V.: Online grocery shopping in Thailand: consumer acceptance and usage behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 48, 224–237 (2019)

DW: COVID: 1 in 4 German retailers face bankruptcy (2021a). https://www.dw.com/en/covid-1-in-4-german-retailers-face-bankruptcy/a-57699502

DW: German retailers brace for the worst as COVID strikes again (2021b). https://www.dw.com/en/german-retailers-brace-for-the-worst-as-covid-strikes-again/a-59897409

Ellison, B., McFadden, B., Rickard, B.J., Wilson, N.L.: Examining food purchase behavior and food values during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 43(1), 58–72 (2021)

Guthrie, C., Fosso-Wamba, S., Arnaud, J.B.: Online consumer resilience during a pandemic: an exploratory study of e-commerce behavior before, during and after a COVID-19 lockdown. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 61, 102570 (2021)

Grashuis, J., Skevas, T., Segovia, M.S.: Grocery shopping preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 12(13), 5369 (2020)

Habib, S., Hamadneh, N.N.: Impact of perceived risk on consumers technology acceptance in online grocery adoption amid covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13(18), 10221 (2021)

Harvard Business Review: Are You Ignoring Trends That Could Shake Up Your Business? (2010). https://hbr.org/2010/07/are-you-ignoring-trends-that-could-shake-up-your-business

Jensen, K.L., Yenerall, J., Chen, X., Yu, T.E.: US consumers’ online shopping behaviors and intentions during and After the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 53(3), 416–434 (2021)

Li, J., Hallsworth, A.G., Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.: Changing grocery shopping behaviours among Chinese consumers at the outset of the COVID-19 outbreak. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 111(3), 574–583 (2020)

McKinsey and Company: COVID-19: Implications for business (2022). https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/covid-19-implications-for-business

Mortimer, G., Fazal e Hasan, S., Andrews, L., Martin, J.: Online grocery shopping: the impact of shopping frequency on perceived risk. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 26(2), 202–223 (2016)

OECD: COVID-19 and the retail sector: impact and policy responses (2022). https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-the-retail-sector-impact-and-policy-responses-371d7599/

Pantano, E., Pizzi, G., Scarpi, D., Dennis, C.: Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Bus. Res. 116, 209–213 (2020)

PWC: Lockdown, Shake Up: The New Normal for Shopping in Europe (2022). https://www.pwc.de/en/retail-and-consumer/european-consumer-insights-series-2020-new-normal.html

Roggeveen, A.L., Sethuraman, R.: How the COVID-19 pandemic may change the world of retailing. J. Retail. 96(2), 169–171 (2020)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Brüggemann, P., Olbrich, R. (2022). The Impact of Pandemic Restrictions on Offline and Online Grocery Shopping Behavior - New Normal or Old Habits?. In: Martínez-López, F.J., Martinez, L.F. (eds) Advances in Digital Marketing and eCommerce. DMEC 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05728-1_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05728-1_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-05727-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-05728-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)