Abstract

Faculty development is crucial to the success of a graduate medical education (GME) program. In designing a faculty development program, GME program directors and planners can use a continuous quality improvement model of needs assessment, topic selection, choosing educational strategies, implementation, and evaluation. Content areas for faculty development include those required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME, i.e., developing faculty as educators, implementing quality improvement and patient safety efforts, delivering high-quality patient care, and fostering well-being), Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) components, and other important topics such as clinical supervision; didactic teaching; diversity, equity, and inclusion; scholarship; and leadership. Faculty development is most effective when it incorporates experiential, multimodal, interactive, and longitudinal learning. Strategies for delivering faculty development can be group or individual, formal or informal, and one-time events versus longitudinal programs. A variety of local and national resources can be helpful in planning faculty development.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Faculty development

- Psychiatry

- Residency

- Graduate medical education

- Professional development

- Teaching faculty

- Program director

Introduction

A skilled, knowledgeable, and enthusiastic faculty is crucial to the success of a graduate medical education (GME) program. Faculty members provide day-to-day clinical supervision, didactic teaching, and mentoring for trainees. They model how psychiatrists work in practice, care and advocate for patients, interact with colleagues, staff, and teams, pursue lifelong learning and scholarship, attend to their own and team members’ well-being, and balance work and personal life. Faculty members substantially affect the safety, inclusiveness, and intellectual stimulation of a trainee’s learning environment. They can observe trainees in their everyday work and provide the specific, direct feedback that a resident needs to become the best possible psychiatrist. For program directors, chairs, and other education program leaders, investing in ongoing professional development of the faculty, or faculty development, is key to establishing and maintaining a high-quality program. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognizes the importance of and provides requirements for faculty development in its Common Program Requirements [1].

Faculty development has been defined as “all activities health professionals pursue to improve their knowledge, skills, and behaviors as teachers and educators, leaders and managers, and researchers and scholars, in both individual and group settings” [2]. This chapter will focus on professional development for faculty participating in graduate medical education (GME) programs. The ACGME describes faculty development as “structured programming developed for the purpose of enhancing transference of knowledge, skill, and behavior from the educator to the learner” and further stipulates that faculty development can occur in a variety of formats, use internal or external resources, is usually needs-based, and can be specific to the program and institution [1].

Through faculty development programming, program directors and leadership can inform and update the teaching faculty about the program’s mission, goals, requirements, and expectations. This process helps faculty members to represent the program accurately to applicants, use effective teaching and supervision methods, foster a positive learning environment, provide meaningful verbal and written feedback to trainees to further their professional growth, and follow program policies correctly. Faculty development events are also opportunities to discuss any upcoming changes in the program.

Faculty development is not just vital for knowledge transfer and skill-building. Group faculty development activities can build community, foster faculty well-being, and enhance satisfaction with and investment in the role of an educator and role model for the next generation of psychiatrists. By paying attention to the group and individual professional development needs of faculty, the program and department can demonstrate their appreciation of faculty members and investment in their success and well-being.

This chapter addresses several areas important in designing or refining a faculty development program for psychiatry GME teaching faculty. These include content areas for faculty development (both those mandated by the ACGME and other important topics) and strategies for delivering and assessing faculty development programming. We provide a model for using a continuous quality improvement approach to guide faculty development efforts. We present two case examples of faculty development challenges and strategies in a new, smaller program and in a larger and more established program. Finally, we discuss local and national resources for faculty development.

Content Areas for Faculty Development

ACGME Requirements

The ACGME Common Program Requirements (CPRs) outline the responsibilities of the program director for faculty (see Box 23.1 for a summary) [1]. These responsibilities fall into two broad categories: ensuring a strong cohort of faculty to lead resident training and overseeing annual faculty development opportunities across core required domains. A high-quality educational environment starts with a strong faculty. The program director not only has the authority to approve faculty for and remove faculty from participation in the training program (per ACGME requirements) but ideally will be involved in hiring and orienting faculty to their educational roles. As part of regular evaluation efforts, the program director is responsible for determining which faculty teach/supervise residents and for monitoring and providing feedback about faculty performance.

These responsibilities require the program director to be broadly invested in the professional development of faculty. Practically, this also means the program director needs to advocate effectively for regular faculty development, including the time for faculty to participate in faculty development, at least annually. Often the program director is supported in these efforts by a range of other faculty leaders, including the department chair and vice-chair for education [3]. There are four topic areas of faculty development required by the ACGME: developing faculty as educators, implementing quality improvement and patient safety efforts, delivering high-quality patient care, and fostering well-being.

Box 23.1: Summary of ACGME Common Core Requirements Related to Faculty [1]

The program director must:

-

Evaluate candidates to participate in the residency program and annually after appointment

-

Approve the supervising faculty, remove faculty from supervisory roles, and have authority to remove residents in cases without acceptable learning environment for all sites

Faculty members must:

-

Demonstrate professionalism

-

Commit to high standards of safe, quality, cost-effective, patient-centered care

-

Demonstrate a strong interest in the education of residents

-

Dedicate sufficient time to their educational role and maintain a high-quality learning environment

-

Participate in professional development and continuing education

-

Engage in faculty development annually in four core areas:

-

Role as an educator

-

Quality improvement and patient safety

-

Fostering well-being (both their own and residents’)

-

Patient care delivery informed by practice-based learning and improvement efforts

-

In addition to these content areas, there must also be a focus more broadly on the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) [4] (see Box 23.2 for details of required areas to consider) and the faculty development needed to promote a high-quality educational environment.

Box 23.2: Summary of Components of Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) [4]

-

1.

Address patient safety and implement sustainable, systems-based improvements

-

2.

Deliver healthcare quality aligned with the goals of the clinical site.

-

3.

Support high-performance teaming.

-

4.

Provide all members of the clinical care team and patients with mechanisms to raise supervision concerns.

-

5.

Engage in systematic and institutional strategies to sustain well-being.

-

6.

Recognize impact of attitudes, beliefs, and skills related to professionalism on quality and safety of patient care.

Developing Faculty as Educators

Developing faculty starts with an orientation to the role of a faculty member as an educator. Tasks of the faculty medical educator include modeling professionalism, demonstrating investment in the education of residents, demonstrating commitment to the delivery of safe, high-quality, cost-effective, patient-centered care, and participating in organized clinical discussions, rounds, journal clubs, and conferences regularly. In order to devote sufficient time to the educational program to fulfill their supervisory and teaching responsibilities, it is also important that faculty understand how to integrate their clinical and teaching responsibilities [1].

Because most clinicians have had limited exposure to formal training in educational strategies and pedagogy, addressing best practices in adult learning may be especially important for faculty to thrive as educators [5]. Common topics of faculty development efforts to enhance teaching abilities include teaching in both didactic and clinical settings, theoretical frameworks and learning approaches, the acquisition of specific teaching skills and strategies, giving feedback, learner assessment and evaluation, and instructional design and curriculum development [6].

Implementing Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Efforts

With the ACGME’s increasing focus on resident engagement in quality improvement and patient safety, there is a growing need for faculty development about both the execution of quality improvement and patient safety projects and the mentorship of trainees in developing these skills [7]. Fortunately, several models support this vital faculty development goal, ranging from weekly emails to enhance patient safety teaching on rounds [8] to more formal system-wide faculty development efforts [9]. In addition, the ACGME Psychiatry Milestones can be a source of core training topics. Common topics of faculty development efforts to enhance quality improvement and patient safety include systemic factors that lead to patient safety events, best practices for reporting patient safety events and error disclosure, analysis of patient safety events, participating in and leading local quality improvement initiatives, and the ability to lead teams to improve systems to prevent patient safety events [10].

Delivering High-Quality Patient Care

Faculty members must model the delivery of up-to-date, evidence-based patient care across both general psychiatry and a range of required psychiatric subspecialty areas. Program directors are responsible for ensuring that faculty members have sufficient expertise to train residents in a broad range of psychiatric clinical rotations, including inpatient, outpatient, geriatric, addiction, community, consultation liaison, forensic, and emergency psychiatry. Additionally, child and adolescent psychiatry experiences require a Board-certified faculty supervisor. Faculty expertise must be available across several treatment modalities, including supportive psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychopharmacology, electroconvulsive therapy, and other emerging somatic treatments [11]. Lastly, faculty experts will be needed to deliver a didactic curriculum across all these topic areas and others. Strategic recruiting of expert clinicians or faculty with subspecialty training may be necessary to address these needs.

Fostering Well-Being

It is especially important to consider the role of the program director in promoting the personal and professional well-being of the faculty. An environment of well-being will enhance faculty job satisfaction and retention. Faculty can also model this important professional activity and be a source of support for resident well-being. There has been increasing recognition that this requires a focus on supporting both systems change in the clinical and learning environment and individual strategies for well-being [12]. Fostering opportunities to create community and promote personal well-being can be incorporated into pre-existing faculty development efforts. For example, faculty development about leading quality improvement projects can include provider satisfaction as an important quality improvement outcome. A program to develop faculty as leaders able to shape the clinical learning environment may also help accomplish the goal of systems that support well-being. To support faculty well-being, the program director and educational leaders may also need to help advocate for appropriate credit for teaching activities [13] or the implementation of innovative programs to promote faculty wellness [14].

Other Potential Topics for Faculty Development

Clinical Supervision

Although developing faculty as educators includes clinical supervision, this topic warrants particular emphasis. The bulk of resident education occurs through clinical supervision, so faculty should be familiar with the principles of adult learning theory and how they apply to supervising residents in clinical settings. Attendings need to be able to assess and activate a resident’s prior knowledge, set collaborative goals, and continuously monitor learning. Supervisors with these skills increase learners’ intrinsic motivation and reflective practice, key elements of the Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) Milestones [15].

Each clinical setting has unique opportunities and constraints that lend themselves to distinct teaching strategies and different faculty development needs. For example, skills needed for brief bedside teaching during inpatient rounds differ from those required for hour-long indirect supervision of a resident doing psychotherapy. Therefore, faculty development programs must recognize and address the unique needs of faculty working in different clinical settings.

In acute care settings, attendings most often work with early learners and have more direct observation of patient interviews with immediate feedback. Some specific tasks for educators in this setting include teaching residents to assess patient safety, maintain their safety working with acute patients, and work collaboratively with multidisciplinary teams [16, 17]. In addition, acute care settings lend themselves to brief bedside teaching. Educators can develop a repertoire of “teaching scripts” for common clinical scenarios in advance. Having prepared “teaching scripts” also can reduce cognitive load to enhance focus on the patient while providing teaching and supervision [18].

In the outpatient setting, attendings generally work with more advanced learners, and there are opportunities for both direct and indirect supervision [19]. Faculty have different teaching opportunities when they join the end of outpatient visits to “staff” cases versus when they provide dedicated indirect group supervision of residents. Indirect supervision (i.e., supervision without personally evaluating the patient) requires different skills to assess and direct learners and may evoke anxiety for faculty new to this model. Specific outpatient supervision skills for faculty include teaching residents safety assessments in the outpatient setting, instructing residents to obtain detailed informed consent for medications, guiding residents in patient panel management, and helping residents refer patients to appropriate community resources [16].

Psychotherapy supervision brings with it another set of skills for faculty development. Attendings need to help residents establish a therapeutic alliance, select a suitable psychotherapy modality, set and maintain boundaries, and complete successful terminations of therapy. There are a host of different strategies that supervisors might use, including observation of video recordings, review of transcripts, role-playing, live observation through a one-way mirror, and co-therapy. Skills that help supervisors form successful supervisory relationships include writing supervision contracts, forming a supervisory alliance, establishing an agenda in supervision, and maintaining appropriate supervision boundaries. Supervisors may also need instruction on using validated empirical scales within their modality to assess resident competency and provide feedback [16].

In all clinical settings, faculty need to be well versed in accurately evaluating residents and providing actionable, specific feedback. Feedback is crucial to learner development, but often faculty receive little training in this area [20]. Faculty development should target using evidence-based solutions and approaches to the most common barriers to feedback, including lack of dedicated time, faculty discomfort and fear of damaging rapport with residents, and discomfort on the part of trainees [21].

Didactic Teaching

In addition to clinical supervision, faculty teach formal didactics, which requires a distinct set of skills. Professional development in this area should include instruction in adult learning theory, specifically in the application of the science of learning to medical education [22, 23]. Engaging adult learners involves tapping into their sources of motivation and making topics relevant to their practice, assessing and building upon prior knowledge, using effortful learning to increase knowledge retention, applying knowledge in varied contexts, and paying attention to the social context of learning. Active learning strategies, such as flipped classroom techniques, problem-based learning, and small group facilitation, can help to increase comprehension, transfer, and retention. Importantly, learning objectives should be explicit and tied to formal assessment tools.

Some examples of successful applications of adult learning theory to medical education include using standardized patients to improve communication skills, using online quizzes to assess knowledge and tailor learning, pairing video clips with skill practice, and using discussion-based vignettes and learner-directed online learning [24]. Another example is team-based learning to improve didactic teaching of psychodynamic psychotherapy within psychiatry residency didactics [25].

Faculty can also learn to develop curricula, for example, by following Kern’s six-step model of problem identification and needs assessment, goals and objectives, educational strategies, implementation, evaluation, and feedback [26]. This model can be successfully applied to developing a didactic series in a specific content area [27, 28].

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Faculty development should include training faculty to foster an inclusive learning environment, evaluate residents equitably and fairly, and educate residents to meet the needs of diverse patient populations.

Program directors are responsible for maintaining an inclusive learning environment for all trainees, including training faculty to be aware of their biases and employ equity mindsets. There are courses available such as “Becoming a More Equitable Educator” from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MITx) [29], and a course specifically designed for graduate medical education is under development. Faculty should be aware that their assessment of residents is prone to implicit bias, which they should consider when completing evaluations and writing letters of recommendation. Implicit bias training is essential for faculty members who rank applicants and select residents for honors, awards, and leadership positions, such as chief residents. In clinical settings, faculty should be trained to support residents who are subject to patient bias. Discriminatory behavior by patients toward trainees is common and takes an emotional toll [30]. There are a variety of frameworks that faculty can use to support trainees and interrupt instances of biased behavior ranging from microaggressions to explicit discrimination [31,32,33].

Faculty should also be trained to provide equitable care to diverse populations and to be able to teach residents to do the same. Concepts of health equity, cultural humility, structural competency, and advocacy should be practiced and taught. Faculty may need specific support to include this content in didactic curricula and avoid bias in all didactics. One institution formed a committee of faculty and residents that led to introducing a 4-year curriculum in cultural psychiatry and religion and spirituality in the residency [34].

Faculty development should also include mentorship of underrepresented minorities in medicine (URM) faculty. Minority faculty development programs increase retention, promotion, and productivity among this cohort [35]. In addition, incorporating development efforts earlier in the pipeline (e.g., for medical students and residents), including mentoring and development of research, teaching, and scientific writing skills, can help retain minority faculty and create an environment conducive to their professional growth [36]. Increased recent comfort with teleconferencing opens up new opportunities for recruiting mentors from remote sites to fill in gaps at a home institution.

Scholarship

The program director is also responsible for supporting the development of a culture of scholarship as outlined by the ACGME requirements:

Medicine is both an art and a science. The physician is a humanistic scientist who cares for patients. This requires the ability to think critically, evaluate the literature, appropriately assimilate new knowledge, and practice lifelong learning. The program and faculty must create an environment that fosters the acquisition of such skills through resident participation in scholarly activities. Scholarly activities may include discovery, integration, application, and teaching [11].

Topics for faculty development efforts include both skills in scholarship and mentoring of trainee scholarship. These activities require various skills, including researching and reading literature, writing and publishing, and presenting scholarship efforts [37].

Developing skills to mentor scholarship is a particular focus, and there are published curricula on developing mentors for scholars, including core topics such as defining mentoring, rewards and challenges of mentoring, communicating effectively with mentees, achieving work–personal life balance, understanding diversity, benefits of informal mentoring relationships, and leadership skills and opportunities [38]. Finally, it is important to note that scholarship is defined by the ACGME much more broadly than just publishing original research. For example, scholarship can include review articles, book chapters, case reports, innovations in education, development of curricula or evaluation tools, quality improvement projects, and contributions to professional organizations or editorial boards. For a detailed discussion of research and scholarship in graduate medical education, see Chap. 26. Many of the faculty development efforts outlined in this chapter, like developing skills in teaching and evaluation, are the foundation of a culture of scholarship.

Leadership

Although not formally an ACGME requirement, developing faculty leadership skills, especially in faculty who serve primarily as clinician-educators, is critical to support a strong program. The program director is often in the position to support the development of leaders in a variety of contexts, from the clinical services in which residents train, to associate program directors, who form a residency leadership team. As with skills in scholarship, most clinicians have not been formally exposed to training in leadership and management. A review of faculty development efforts to promote leadership reports topics such as leadership concepts, principles, and strategies (e.g., leadership styles and strategic planning), leadership skills (e.g., personal effectiveness and conflict resolution), and increased awareness of leadership roles in the academic setting [39]. This review also notes that common areas of change after faculty development include both changes in awareness of one’s role as a leader and participants taking on new leadership roles. Suggestions for faculty development include grounding efforts in a theoretical framework, articulating the definition of leadership, delivering faculty development in the form of extended rather than one-time programs, and promoting the use of narrative approaches, peer coaching, and team development. It is important to note that many leadership development efforts have focused on higher level leadership roles such as department chairs and executives. A recent paper by Survey and colleagues describes a successful leadership curriculum designed for program and clerkship directors [40]. This curriculum was a week-long course that covered both educational topics (assessment and curriculum design, mentoring, and program evaluation) and leadership topics (change management, communication, negotiation, conflict management, emotional intelligence, leadership style, management, mission and vision, and team building). Innovative approaches described by this group include inviting specific faculty to participate in the course based on their leadership role and using responses from a series of prework reflection assignments to anchor course content. These examples may be helpful to guide program director decisions as they develop local efforts to support faculty development for leadership.

Strategies for Faculty Development

The content of faculty development described above can be delivered in a variety of different ways. Traditionally, faculty development has involved one-time structured group lectures or workshops sponsored by a department or institution. However, the literature now describes a broader range of faculty development strategies. Steinert [41] has divided these into group versus individual approaches that are either formal or informal. Faculty development activities can also be divided into one-time events such as a single workshop versus longitudinal interventions such as courses, teaching scholars programs, or communities of practice that meet over weeks to years.

Several studies have examined factors contributing to the effectiveness of faculty development programs in terms of participant satisfaction, learning, and behavior change, as well as (rarely) student and organizational change. A common thread in these studies is the crucial importance of adding experiential learning to grounding didactics. Experiential learning includes practicing and applying knowledge and skills, both as part of the faculty development program and within the participant’s workplace. Other important factors identified in reviews of faculty development interventions to enhance teaching effectiveness and leadership skills [6, 39] include the use of an evidence-informed educational design, the use of multiple instructional methods within a single intervention to enhance learning, content relevant to participants’ work, opportunities for feedback and reflection, a longitudinal design rather than one-time events, individual and group projects, peer support, intentional community building, and institutional support in the form of funding and release time for participants. A review of studies addressing faculty development for competency-based education [42] identified key features of a shared mental model regarding learner (e.g., resident or fellow) competencies, feedback for participating faculty members regarding their teaching and assessment skills, and longitudinal faculty development programming.

Below, the different faculty development strategies are reviewed in more detail, organized according to Steinert’s [41] model of group versus individual and formal versus informal approaches. Programs will likely wish to use multiple strategies depending on the purpose and topic of faculty development, available resources, and the needs and preferences of their faculty members. Faculty members at various stages of career development are also likely to have different faculty development needs [43].

Group Faculty Development

Formal Activities

Formal, structured group activities are the most frequently implemented faculty development strategies in medicine [6]. One-time lectures or workshops are a low barrier strategy to reach many faculty members. Workshops offer an opportunity to learn and practice educational skills through active instructional methods such as structured reflection, small group discussions, and role-plays or simulations. One-time faculty development events receive very high satisfaction ratings from faculty. Some studies have found that they increase self-reported knowledge, skills, and confidence and change participant behavior. For example, a half-day faculty workshop on mentoring improved measured mentoring competency and self-reported skills and confidence [44].

Longitudinal experiences require more development, time, and resources but tend to be more sustainable and produce higher level behavioral changes (e.g., enhanced educational leadership and scholarship) [6]. Longitudinal experiences may include short courses or seminars or longer (e.g., year-long) programs. In addition, novel longitudinal programs for junior faculty have been created at various institutions, with components of teaching education skills, mentoring and setting career goals, assisting with the completion of participants’ projects, and providing a community of peer support [45,46,47].

Education Grand Rounds are a common way to incorporate teaching topics into a longitudinal format. One academic center found this method to be a sustainable form of faculty development across two campuses, with prioritized themes including didactic and clinical teaching, education research, assessment and evaluation, education administration, and instructional technology [48]. While faculty development events are usually just for faculty members, Education Grand Rounds can also provide an opportunity for other learners, such as residents, fellows, and students, to learn about important topics in education.

Many universities offer teaching scholars programs within their departments or health sciences [49]. These programs involve instruction in teaching methods, educational research and scholarship, curriculum development, assessment skills, advising and mentoring skills, and leadership skills. Outcomes of these programs include increased enthusiasm for teaching and increased productivity in educational research, including publication and presentation at professional meetings. Some academic centers have formal master’s degrees or fellowships in medical education, generally within the school of medicine or health sciences [50].

In psychiatry, like the rest of medicine, most faculty development remains structured group one-time events rather than longitudinal programs. For example, in a 2016 survey of members of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT), only 16% of respondents identified any longitudinal faculty development at the department level. In addition, only 11% reported longitudinal programs within their institution [3].

Informal Activities

Less formal group strategies foster workplace-based learning and local “communities of practice” [51], where clinician-educators can be more vulnerable, strengthen their social network, hone each other’s teaching skills, and work together on projects. Informal strategies can be added or built into pre-existing clinical and service-related activities. For example, department or site faculty meetings can devote a portion of time or a periodic meeting to a faculty development topic. Journal clubs are another opportunity for selecting articles on education-related topics. Clinical service meetings and clinical consultation groups can also be used as a potential forum to discuss teaching topics, coordinate feedback for learners, and brainstorm solutions to challenging scenarios as they arise. Small groups of faculty members on an acute service or within a clinic can meet at regular intervals, for example, before learner evaluations are due, to support each other in developing and delivering constructive, targeted feedback.

Faculty peer groups can support each other in developing clinical skills, career development, and leadership. For example, one institution successfully formed a monthly peer group using a case-based model to discuss challenging scenarios, such as assisting medical students in coping with patient death, supporting students who were victims of sexual harassment, managing medical students with their own mental illnesses, and personal self-disclosure in clinical encounters [52]. Another peer group of junior clinician-educator faculty met 30 times over 5 years with a senior faculty advisor. They used a model of having each junior faculty member report on their career-related progress and concerns, receive feedback from the group, and form an action plan of steps to accomplish before the next meeting. Goals were mutual support, providing collective mentoring, fostering accountability, maintaining momentum on projects, and helping junior faculty meet requirements for promotion [53]. Outcomes included increased workplace satisfaction and scholarly productivity.

Small peer reflective-practice groups can help faculty gain alternative perspectives and novel solutions to common issues of clinical practice and leadership. For example, one small group used an iterative strategy of alternating between structured individual reflective writing and group discussion to develop new approaches to manage disruptive physician behavior [54].

Workplace-based groups of faculty members can work together on group projects addressing specific goals. For example, in one program, a working group of six faculty leaders of core modules in the psychiatry residency didactics successfully revised the curriculum of their modules, with the specific goals of updating and coordinating content (e.g., eliminating gaps and redundancies) and incorporating more active teaching strategies [55]. The group met for 90 min every 2 months and achieved this revision without additional compensation or dedicated time. These junior faculty, led by the program director, simultaneously developed their instructional competence and enhanced their curriculum development and leadership skills. Another working group at the same institution convened to develop a novel curriculum for the new integrated care fellowship within 6 months of its starting date. The group was successful with the support of two staff with education expertise working at 1.0 full-time equivalents (FTE) total and with dedicated FTE provided to involve faculty [27]. Within the same fellowship, another working group of four faculty produced a novel 12-h telepsychiatry curriculum [28]. Group projects, supported by peers or by teleconferenced distance mentoring at a national level, are also a low-cost and effective way to foster scholarship among clinician educators [56].

Individual Faculty Development

Formal Activities

A faculty member’s areas of interest and career goals should guide their individualized faculty development. Departments can provide resources or time for faculty to complete online training or continuing medical education (CME) activities, attend national conferences, and purchase books and other resources.

Opportunities for individual professional development exist in clinical settings in the form of evaluations from learners. Faculty may receive formal evaluations of their didactics from learners as well as evaluations in their capacity as supervising attendings for rotations. These evaluations provide feedback about the faculty member’s teaching skills and have the added benefit of documenting teaching activities for promotion and tenure. Peer evaluations of teaching and clinical activities provide another unique perspective for further development. One institution provided faculty with aggregated peer evaluations assessing domains related to clinical practice, teaching, departmental citizenship, and research/productivity [57].

More targeted and direct feedback can be delivered through direct observation. For example, faculty can observe a peer’s didactic session and complete a structured peer teaching evaluation. One such instrument was created with faculty input to evaluate medical lecturing. With peer rater training, internal consistency was high, and this method served as a reliable peer assessment for the promotion process [58]. Peer faculty can also directly observe others doing group or individual supervision or informal teaching in a clinical setting, with structured prompts for feedback. “Peer coaching” has been used to identify specific goals for improving teaching skills in the clinical setting in a longitudinal model, resulting in increased self-awareness, improvement of specific skills, and fostering collegiality [59]. In a study of internal medicine faculty attendings on 2-week inpatient teaching blocks, direct observation by peers using a structured tool was positively received by both evaluators and those observed [60]. Being observed led to the awareness of unrecognized habits and personalized teaching tips. Evaluators reported learning new and useful teaching techniques from their peers. In another study, peer collaborative relationships in which faculty work together to plan educational activities and monitor implementation led to faculty members’ implementing new teaching strategies, appropriately choosing new teaching strategies, and retaining these strategies in the long term [61].

Formal faculty development at the individual level can also include completion of online modules required by the program or institution, focusing on topics such as assessing learners using direct observation, giving feedback, or fostering an inclusive and positive learning environment. Some national online modules or courses are listed in Table 23.1, with topics including learner assessment, becoming an equitable educator, and Psychiatry Milestones. Online modules help deliver core information deemed important for every faculty member to know. In addition, online modules and in-person faculty development events can benefit from the principles underlying faculty development “snippets” [62]. “Snippets” aim to reduce cognitive load by focusing on a single objective, covered in about 10 slides, lasting 15–20 min, and can be delivered by themselves or paired with a well-aligned learning activity as part of a longer faculty development session or program. As discussed above, the ability to apply knowledge, practice skills, and receive feedback is important in consolidating learning from online modules or didactic “snippets.”

Mentorship is vital to individual faculty development. One faculty survey indicated that having a high-quality mentor increased job satisfaction and decreased the chances of being stalled in rank [63]. Formal mentoring programs exist in many departments and institutions, commonly involving mentor–mentee dyads, often with written agreements and expectations. Thus, mentorship is discussed here as a formal faculty development strategy at the individual level. However, mentoring can occur informally, with successful faculty members often finding multiple mentors and sponsors, and can also occur in group settings with one or more senior mentors, peer mentoring groups, or speed mentoring [64]. One formal program assigned mentors to new faculty members, provided mentors with an orientation, and gave a list of six topics to the pairs to discuss in regular mentoring sessions (orientation to the department, clinical and administrative duties, research and academic interests, teaching and supervision assignments, personal and family well-being, and promotion and tenure) [65]. In a systematic review of studies of mentoring programs for URM physicians in academic settings, strategies included peer, senior faculty, onsite, and distance mentoring either individually or in groups [66]. Key themes included the importance of institutional support and mentor training.

Informal Activities

While harder to identify, a significant component of faculty development is experiential learning through job-related activities. One framework to understand experiential learning is described by Steinert as learning by doing, observing, and reflecting [51]. Faculty members can be encouraged to enhance their skills by setting goals for themselves, keeping a log of their teaching experiences, or by reflecting on their teaching through a series of structured prompts.

Within academic settings, many clinicians practice in teams and can observe others’ styles and approaches, including those of peers and learners. Informal peer interactions allow for faculty to compare experiences, reflect on shared patients, and provide each other with informal feedback. Faculty may also find multiple informal mentors within their social networks.

Using a Continuous Quality Improvement Approach to Guide Faculty Development

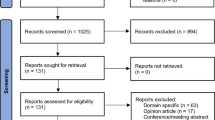

Usually, a combination of the above strategies will be required to meet the needs of each individual program and its faculty. A continuous quality improvement approach offers the opportunity to identify gaps, opportunities, and barriers and iteratively assess effectiveness, thus allowing for revision of strategies. See Fig. 23.1 for a visual representation of this process.

Needs Assessment

When doing a needs assessment, programs should consider their existing structures for faculty development, with strengths and weaknesses. For example, surveys or focus groups of junior faculty can elicit areas of anxiety or discomfort, familiarity with adult learning theory, degree of connectedness to peers, level of understanding of department culture, and familiarity with requirements for promotion. Feedback from senior faculty can indicate which faculty development strategies and content areas were important for their success and which they wish they had known earlier. Input from residents or fellows can give a sense of how faculty are currently performing as educators and whether residents are receiving effective and helpful feedback. Focus groups, surveys, and larger anonymous program evaluations are ways of eliciting resident and fellow input.

Topic Selection

Results of the needs assessment should guide the selection of topics to fill in areas of deficiency. Particular attention should be given to making sure faculty development efforts meet ACGME requirements and satisfy components of CLER. Once these requirements are met, attention can be given to further developing topics pertinent to specific areas of faculty expertise, clinical supervision in different clinical settings, didactic teaching, and developing faculty as scholars and leaders. Throughout all faculty development efforts, attention should be given to developing faculty as equitable educators who create an inclusive learning environment for all.

Strategy Selection

Certain strategies may align better with given content areas. For example, developing faculty expertise within specific treatment modalities and subspeciality areas may need to be more individualized and include activities such as support to attend specialty meetings or for mentorship with expert clinicians. Often a variety of approaches may be necessary to target a given content area. For example, different strategies can be used to develop scholarship skills for faculty. Such strategies range from local individual mentorship of specific scholarly projects to formal, comprehensive educational scholarship programs. At a national level, these include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Medical Education Research Certificate (MERC), the Association for Academic Psychiatry (AAP) Master Educator program, and others listed in Table 23.1, which present formal curricula to develop educational scholarship skills. Some institutions have also developed local formal programs. For example, the Medical Education Scholars Program at the University of Michigan delivers a year-long project-based program to develop a small group of faculty members from basic and clinical science departments throughout the medical school [37]. This program has been shown to increase the number of new educational programs and grants led by participating faculty. However, access to these formal programs can be limited by a small number of participants or the cost to participate, so alternative low resource approaches are another important approach to developing scholarship. Yager and colleagues outline a pragmatic approach that starts with assessing motivation and then provides practical solutions to identify opportunities for and engage in scholarship [67].

Implementation

Once high-yield topic areas have been identified, a program should determine how they are best taught in their unique settings. Next, program directors can consider whether departmental, institutional, or national resources can be leveraged. Program directors may wish to identify collaborators, such as the vice-chair for education, medical directors, associate program directors, and content area experts. For larger efforts aimed at reaching all faculty or the implementation of sustainable, longitudinal programs, program directors should collaborate with the department chair, service chiefs, and other leaders to secure funding and other needed resources. Results from the needs assessment may make a case for resources more compelling, especially if there are data on effects on faculty satisfaction and retention. The most common barriers to faculty development include lack of funding and faculty time [3].

Practical considerations include the size of the program and number of diverse sites, whether efforts will be in-person or virtual, whether activities can occur during business hours, how faculty will be released from clinical duties, whether there are resources to provide “perks” such as food, and whether activities can provide faculty with formal continuing medical education (CME) credit. There may be times when faculty members already come together as small or large groups (e.g., faculty meetings, Grand Rounds) where professional development activities can be folded in.

Evaluation

Once a set of strategies has been implemented, ongoing assessment is needed to refine efforts and direct resources appropriately. Faculty satisfaction with professional development activities can be assessed directly after trainings or workshops and globally at periodic intervals. Formal group activities targeting specific skills lend themselves to assessing changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes before and after training. For example, the objective structured teaching exercise (OSTE) [68] uses standardized students and teaching scenarios to assess faculty teaching and interpersonal communication skills. When used pre- and post-training, it is an effective way to evaluate the benefits of faculty development programs. Higher order assessments are more challenging but measure desired outcomes such as faculty behavior change and effects of faculty development on learners and at an organizational level. For example, changes in individual faculty behavior (i.e., use of new skills in their clinical and didactic teaching) can be assessed through changes in their formal peer and learner evaluations or observation by peers. Over time, broader effects of faculty development can be assessed through faculty retention, promotion, and scholarly products.

Case Examples

Program A is a new, small, community program with 12 core faculty members and a planned cohort of 12 residents working in one medical system with a robust psychiatric service. This program is affiliated with a larger established program (program B) that provided mentorship to program A’s founding program director. As program A is new, most faculty are new to a teaching role, and several are recent residency graduates. There are opportunities to participate in program B’s annual faculty development program remotely. The program director has one year to prepare the faculty to welcome their first class.

The program director is concerned because several faculty members have expressed anxiety over their new teaching responsibilities, especially the time necessary to engage in faculty development and supervision once the residents start, as most faculty already feel busy with their current clinical duties. There is general support from the medical system as there has been a successful family medicine program within the system for the last five years. The program director decides to start with three main topic areas: foundational clinical teaching skills for inpatient settings, core psychiatry teaching areas for junior residents to deliver clinical care, and conducting clinical skills exams to meet accreditation and Board requirements. Since there is limited local expertise, the program director decides to approach faculty development by creating a six-session faculty development series held by expanding the length of the regularly scheduled faculty meeting, which all faculty attend, and engaging support from faculty mentors from the local family medicine faculty for general teaching skills (e.g., integrating clinical supervision into inpatient services), utilizing AADPRT Virtual Training Office materials on core topics (e.g., clinical skills exam) and inviting faculty from program B to present additional psychiatry specific topics (e.g., teaching psychiatry differential diagnosis). This faculty development plan is fully supported, including an extra hour for the faculty meeting, by the CEO of the medical system after advocacy by the program director.

A new program often benefits from leveraging excitement and positive energy about the new program to engage faculty in faculty development. This can be helpful to activate faculty learners as they will soon have to be engaged in teaching. Program A also benefits from a current residency program in their clinic system and mentorship from an established psychiatry residency program (program B). However, a new program often has the challenge of limited local expertise to draw on to lead faculty development efforts. There is an additional challenge of establishing a faculty development program with a group of busy clinicians who have limited time to meet as a group. Finally, it can be challenging to develop teaching skills before there are residents to teach.

As there are many potential faculty development targets and limited time, it will be important for the program director to complete a needs assessment that prioritizes topic areas needed for resident instruction for first-year residents. The program director will want to prioritize the four key areas identified by the ACGME for annual faculty development (developing faculty as educators, implementing quality improvement and patient safety efforts, delivering high-quality patient care, and fostering well-being) as well as core instructional activities (e.g., direct clinical supervision, assessing Milestone progress, and administering clinical skills exams). Another important consideration will be asking the faculty which areas of faculty development they think are most important for them to feel prepared for the new residents. Next, the program director needs to pick strategies that are realistic for the context of the program. Finding a regular time to engage in faculty development (e.g., monthly faculty meetings) will be important so that all faculty develop the skills necessary to supervise and teach residents. Utilizing available resources, such as local experts, national resources, and invited speakers can be an effective strategy to augment the limited expertise of a new faculty group.

This example also illustrates how important the program director’s advocacy role is to implement faculty development and teaching support. Understanding that there are faculty concerns about time to teach requires discussion with the clinical leadership to make sure that clinical schedules are adjusted to allow enough time for supervision of residents. It is also important that faculty have protected time, like extended faculty meeting time, to participate in faculty development without added burden on faculty. Lastly, the program director will want to monitor the impact of this faculty development effort on faculty engagement and skills, resident satisfaction with teaching, and progress in the development of residents’ clinical skills. This evaluation will be important as part of the needs assessment for the next round of faculty development the program director will plan.

Program C is a large, urban, multisite, university-based residency with 64 general psychiatry residents, over 200 faculty members, and 4 main clinical sites. There are also about 150 community volunteer faculty who provide psychotherapy supervision. The program hosts an annual faculty development half-day (faculty teaching retreat), which has been in-person in the past and virtual for the past two years. The retreat uses interactive workshops to teach skills as an educator (e.g., teaching skills, curriculum development, assessment, giving effective feedback, and Milestones), faculty and resident well-being, quality improvement and patient safety, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (e.g., racism, microaggressions, fostering an inclusive learning environment). The program director is concerned because only 35–40 faculty members attend the teaching retreat each year. Despite repeated teaching retreat sessions about giving feedback, residents continue to request more specific and useful feedback on clinical rotations. The Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) continues to be concerned about the wide range and “grade inflation” of faculty Milestone ratings of residents. The program director surveys faculty and discovers that they have difficulty finding time or clinical coverage to attend the teaching retreat. In addition, they have trouble knowing how to fit feedback into their busy clinical day. With the support of the department chair, the program director makes a plan with each clinical site director to provide clinical coverage so that most faculty can attend the retreat and works with site directors and associate program directors to incorporate 20-min faculty development sessions into the site’s faculty meeting on a quarterly basis. The program also convenes a group to work on a quality improvement project focusing on feedback. This group develops a templated, structured feedback app designed to help supervisors give brief, focused feedback based on direct observation and provides practice and feedback in using the app during site-based faculty development sessions.

Large and university-based programs like program C have several strengths to draw upon in planning faculty development. First, many faculty members are potential faculty development teachers and mentors in a variety of topic areas. Second, program C’s department may have a variety of other educational programs, such as psychiatric subspecialty fellowships and programs for learners in other mental health professions. This creates the possibility of interprofessional faculty development and projects. Finally, it is also likely that there are rich institutional resources available, such as institutional faculty development events, teaching scholars programs, teaching academies, and medical education departments with expertise in curriculum development, instructional design, and the use of technology in education.

However, program C has several challenges in delivering faculty development. Having a large faculty distributed across sites makes it difficult to foster a sense of cohesion and build a learning community. Faculty members may not know or may not even have met colleagues at other sites and may feel less motivated to get together for faculty development events. Fundamental logistical issues, such as finding a time for faculty development sessions, can be complex, given the differing schedules of the considerable number of people involved. In addition, routine occasions when faculty might come together, such as faculty meetings or case conferences, may be at different times at each site. Given these challenges, the low attendance at program C’s teaching retreat is not surprising.

As in a program of any size, needs assessment is important for program C to identify core faculty development content the program wishes to deliver and the professional development needs of faculty. In this example of a program with an existing faculty development program, past participant evaluations and the program director’s concerns inform the needs assessment, which includes a faculty survey to identify barriers to attending the teaching retreat, obstacles to providing helpful Milestones assessment and feedback, and faculty preferences about alternative ways to deliver faculty development content.

In general, there are key topics that a particular program’s leadership wants to ensure that all teaching faculty members learn about in any given academic year. These might include national changes in psychiatry graduate medical education (e.g., new Milestones) or local issues. In program C’s case, high-priority program-wide topics are feedback and Milestones assessments. The challenge in a large program is to find strategies that maximize all faculty members’ involvement. Perceived professional development needs of the faculty may or may not overlap with program priorities and may vary at different clinical sites or in subgroups of faculty based on factors such as work setting and role (e.g., inpatient, consultation-liaison, outpatient, psychotherapy supervision) or developmental career stage. Especially in a large program, one approach is to do needs assessment and faculty development programming at the level of these smaller faculty groups. This maximizes the chance that faculty development will be relevant and lends itself to community building, peer mentoring, communities of practice, and group projects within and across sites.

Institutional support is crucial in ensuring that all faculty members can participate in faculty development. Faculty may need financial support, release time, and clinical coverage to attend faculty development events. Again, the example of program C points out the importance of the program director’s advocacy role. Enlisting the aid of the chair and the clinical service directors facilitated faculty attendance at program-wide and site-based faculty development events. The department chair and clinical site directors must attend faculty development events themselves and emphasize their importance to their faculty members.

The program can also teach about high-priority topics using multiple strategies at the same time. For example, in thinking about strategies for faculty development, program C could choose to cover topics such as feedback and Milestones assessments in different venues, e.g., as part of the teaching retreat, at the new site-based meetings, and using online modules. The program and department could require that each faculty member attend or complete at least one of these activities each year.

Some issues are longstanding and require culture change. For example, program C has recurrent problems with feedback and Milestone assessments. In addition to ensuring that all faculty participate in one-time events addressing these issues, the program can decide that these areas require more sustained quality improvement. One approach is to form faculty communities of practice to work together over time to address such problems through cycles of problem identification, planning, acting, observation of results, and reflection. In this case example, program C decided to form such a group focused on feedback. Twelve specific tips for creating effective communities of practice have been outlined by de Carvalho-Filho et al. [65]. Ideally, they include support (e.g., a budget, space, technical and staff support, protected time), communication of successes of the group to the broader department and institution, and recognition of contributions of individual members (e.g., in the promotions process and through the publication of the process and results). In addition, members of communities of practice, or other peer champions and guides, can help educator faculty to accomplish needed behavioral changes (e.g., using the new feedback app) by honoring colleagues’ current contributions, demonstrating how new behaviors build on existing skillsets, and providing information and support on an individual basis or through faculty development events focused on skill acquisition, practice, and feedback [69].

Program C will want to evaluate the effectiveness of its newly implemented faculty development strategies through feedback from faculty, residents, and the CCC and use evaluation results to modify the faculty development program further.

Resources

Programs do not need to start from scratch in designing faculty development programming; they can instead take advantage of a wealth of local and national resources. In this section, we discuss a general strategy for identifying such resources. In addition, faculty development resources for specific topics (e.g., assessment, professionalism) are discussed in detail in other chapters in this book.

After performing a needs assessment and identifying topics, program directors and other faculty development planners will want to choose educational strategies and then design, implement, and evaluate the program (see Fig. 23.1). In doing this, they can first look for collaborators and existing faculty development programs in their own department and institution. Consultation with educator faculty members within the department, other departments, and the institution can help in choosing educational strategies, designing faculty development curricula, implementing specific teaching methodologies, and identifying content experts and instructors. Other departments may have experience delivering faculty development about particular topics, especially those mandated by the ACGME, have advice about what has worked well, and provide specific curricular materials or recommendations for speakers. Many institutions host faculty development sessions for faculty across specialties focused on promotion, leadership, quality improvement and patient safety, educator skills, and scholarship. Programs can alert their faculty to these opportunities and assess whether they need or want to duplicate this content within the department. Faculty or staff within the department or institution with expertise in instructional design, interactive teaching methods, and technology in education can be excellent resources in building curricula and designing individual sessions.

Programs can also collaborate with nearby GME programs, other educational programs within their own or nearby psychiatry departments (e.g., subspecialty psychiatry fellowships, psychology, and social work training programs), and nonmedical school university departments (e.g., psychology, sociology, public health) around specific faculty development topics (e.g., diversity, equity, and inclusion, interprofessional teamwork, well-being, didactic and classroom teaching methods). Remote collaborations are also possible. For example, in the first case example above, faculty at program A were able to participate virtually in the annual teaching retreat at program B, which had an established faculty development program.

Usually, programs do not need to design de novo faculty development programming in patient care. Instead, individual faculty members conduct practice-based learning activities as part of Maintenance of Certification, and departments usually sponsor Grand Rounds and clinical case conferences. Faculty members can also increase their clinical expertise through local and national clinical training, workshops, conferences, and mentorship. Programs will probably want to design specific faculty development in quality improvement and patient safety; however, departments and institutions have ongoing quality improvement and patient safety initiatives that faculty members may participate in for hands-on experience in this area.

In some areas of faculty development (e.g., diversity, equity, and inclusion), local content expertise may be hard to find. Engaging faculty development teachers from across the institution and nationally is especially important in these cases, as is the consideration of hiring or developing psychiatry faculty experts. Sotto-Santiago et al. [70] provide a framework for antiracism education for faculty development and give examples of specific interventions in the authors’ institutions. In addition, the ACGME is developing and curating educational resources about diversity, equity, inclusion, and antiracism through its ACGME Equity Matters™ initiative [71]. These resources promise to be helpful for GME programs in designing faculty development in this area.

Table 23.1 lists some examples of national faculty development resources. National psychiatric education organizations such as AADPRT, AAP, and the Association of Directors of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry (ADMSEP) provide annual meeting presentations, programs, and resources in faculty development, educator skills, and educational scholarship. Importantly, these organizations offer national networking, community, and mentorship for psychiatric educators and opportunities to present scholarly work. National curricula, such as the National Neuroscience Curriculum Initiative (NNCI), can be a valuable source of both increased knowledge and state-of-the-art pedagogy. Table 23.1 also includes national in-person and online faculty development programs in leadership, scholarship, educator skills and innovation, quality improvement and patient safety, learner assessment, and diversity, equity, and inclusion. Departments can foster the professional development of their teaching faculty by informing them of such programs, nominating them, and providing financial support and time for them to attend.

Summary and Key Points

Developing faculty as successful educators, supervisors, leaders, scholars, mentors, and role models for residents/fellows is essential to the success of a graduate medical education program. Faculty development is vital to ensuring a safe and inclusive learning environment for all trainees.

Areas for faculty development include domains within the ACGME requirements (developing faculty as educators, implementing quality improvement and patient safety efforts, delivering high-quality patient care, and fostering well-being), CLER components, and other areas (e.g., clinical supervision, didactic teaching, diversity, equity and inclusion, scholarship, and leadership). Strategies for faculty development can include group versus individual programs, formal versus informal activities, and one-time events versus longitudinal programs. Program size and resources are important considerations as a program director plans for faculty development. There are many national resources to draw on as well as potential local resources for these efforts.

Program directors can use a continuous quality improvement approach to conduct a needs assessment, choose content areas, select appropriate strategies, implement changes, and use iterative assessments to evaluate and refine faculty development efforts. The main barriers to faculty development efforts are a lack of funding and time. Program directors should collaborate with their department chair, service chiefs, and other leaders to secure funding, release time for faculty, and other needed resources. In addition, they can use the results from their needs assessment to help their advocacy efforts, especially if there are data on effects on faculty satisfaction and retention.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/common-program-requirements/

Steinert Y, editor. Faculty development in the health professions – a focus on research and practice. Springer; 2014.

De Golia SG, Cagande CC, Ahn MS, Cullins LM, Walaszek A, Cowley DS. Faculty development for teaching faculty in psychiatry: where we are and what we need. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):184–90.

Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Initiatives/Clinical-Learning-Environment-Review-CLER/

Ramani S, Orlander JD, Strunin L, Barber TW. Whither bedside teaching? A focus-group study of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(4):384–90.

Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, Barnett BM, Centeno A, Naismith L, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: a 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769–86.

Baron RB, Davis NL, Davis DA, Headrick LA. Teaching for quality: where do we go from here? Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(3):256–8.

Roy MH, Pontiff K, Vath RJ, Bolton M, Dunbar AE. QI-on-the-fly: continuous faculty development to enhance patient safety teaching and reporting. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):461–2.

van Schaik SM, Chang A, Fogh S, Haehn M, Lyndon A, O’Brien B, et al. Jump-starting faculty development in quality improvement and patient safety education: a team-based approach. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1728–32.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Psychiatry Milestones 2.0 [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sept 14]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Milestones/pfcatid/21/Psychiatry/

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/specialties/program-requirements-and-faqs-and-applications/pfcatid/21/psychiatry/

Houston LJ, DeJong S, Brenner AM, Macaluso M, Kinzie JM, Arbuckle MR, et al. Challenges of assessing resident competency in well-being: development of the psychiatry milestones 2.0 well-being subcompetency. Acad Med. 2021;97(3):351–6.

Regan L, Jung J, Kelen GD. Educational value units: a mission-based approach to assigning and monitoring faculty teaching activities in an academic medical department. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1642–6.

Fassiotto M, Simard C, Sandborg C, Valantine H, Raymond J. An integrated career coaching and time-banking system promoting flexibility, wellness, and success: a pilot program at Stanford University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):881–7.

Goldman S. Enhancing adult learning in clinical supervision. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35(5):302–6.

De Golia SG, Corcoran KM. Supervision in psychiatric practice: practical approaches across venues and providers. American Psychiatric Pub; 2019. p. 460.

Greenberg WE, Borus JF. Focused opportunities for resident education on Today’s inpatient psychiatric units. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):201–4.

Cawkwell PB, Jaffee EG, Frederick D, Gerken AT, Vestal HS, Stoklosa J. Empowering clinician-educators with chalk talk teaching scripts. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):447–50.

Reardon C, May M, Williams K. Psychiatry resident outpatient clinic supervision: how training directors are balancing patient care, education, and reimbursement. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):476–80.

Anderson PAM. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):154–8.

McCutcheon S, Duchemin A-M. Overcoming barriers to effective feedback: a solution-focused faculty development approach. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:230–2.

Gooding HC, Mann K, Armstrong E. Twelve tips for applying the science of learning to health professions education. Med Teach. 2017;39(1):26–31.

Kaufman DM. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):213–6.

Reed S, Shell R, Kassis K, Tartaglia K, Wallihan R, Smith K, et al. Applying adult learning practices in medical education. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44(6):170–81.

Touchet BK. A pilot use of team-based learning in psychiatry resident psychodynamic psychotherapy education. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):293–6.

Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. JHU Press; 2016. p. 313.

Toor R, Cerimele JM, Farnum M, Ratzliff A. Longitudinal faculty development in curriculum design: our experience in the integrated care training program. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(6):761–5.

McCann RA, Erickson JM, Palm-Cruz KJ. The development, implementation, and evaluation of a novel Telepsychiatry curriculum for integrated care psychiatry fellows. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(4):451–4.

Becoming a More Equitable Educator: Mindsets and Practices [Internet]. edX. [cited 2021 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.edx.org/course/becoming-a-more-equitable-educator-mindsets-and-practices

Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, Pfeffinger A, McMullen A, Critchfield JM, et al. Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1678–85.

Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD, Wilkins KM. ERASE: a new framework for faculty to manage patient mistreatment of trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):396–9.

Shankar M, Albert T, Yee N, Overland M. Approaches for residents to address problematic patient behavior: before, during, and after the clinical encounter. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):371–4.

Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1112–7.

Lim RF, Luo JS, Suo S, Hales RE. Diversity initiatives in academic psychiatry: applying cultural competence. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):283–90.

Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Fogarty JP, Williams RL. Underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine: a systematic review of URM faculty development. Fam Med. 2014;46(2):100–4.

Johnson JC, Jayadevappa R, Taylor L, Askew A, Williams B, Johnson B. Extending the pipeline for minority physicians: a comprehensive program for minority faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):237–44.

Gruppen LD, Frohna AZ, Anderson RM, Lowe KD. Faculty development for educational leadership and scholarship. Acad Med. 2003;78(2):137–41.

Sood A, Qualls C, Tigges B, Wilson B, Helitzer D. Effectiveness of a faculty mentor development program for scholarship at an academic health center. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2020;40(1):58–65.

Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):483–503.

Servey JT, Hartzell JD, McFate T. A faculty development model for academic leadership education across a health care organization. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520948878.

Steinert Y. Becoming a better teacher: from intuition to intent. In: Theory and practice of teaching medicine. American College of Physicians; 2010. p. 73–93.

Sirianni G, Glover Takahashi S, Myers J. Taking stock of what is known about faculty development in competency-based medical education: a scoping review paper. Med Teach. 2020;42(8):909–15.

Teshima J, McKean AJS, Myint MT, Aminololama-Shakeri S, Joshi SV, Seritan AL, et al. Developmental approaches to faculty development. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(3):375–87.

Lau C, Ford J, Van Lieshout RJ, Saperson K, McConnell M, McCabe R. Developing mentoring competency: does a one session training workshop have impact? Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):429–33.

Fertig AM, Tew JD, Douaihy AB, Nash KC, Solai LK, Travis MJ, et al. Developing a clinician educator faculty development program: lessons learned. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(3):417–22.

Gould NF, Walsh AL, Marano C, Roy D, Chisolm MS. The psychiatry academy of clinician educators: a novel faculty development program. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(6):814–5.

Tong L, Hung E. A novel department-based faculty fellowship to promote scholarship in medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):402–5.

Medina M, Williams V, Fentem L. The development of an education grand rounds program at an academic health center. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:30–6.

Fidler DC, Khakoo R, Miller LA. Teaching scholars programs: faculty development for educators in the health professions. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):472–8.

Cohen R, Murnaghan L, Collins J, Pratt D. An update on master’s degrees in medical education. Med Teach. 2005;27(8):686–92.

Steinert Y. Faculty development: from workshops to communities of practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(5):425–8.

Joy JA, Garbely JM, Shack JG, Kurien M, Lamdan RM. Supervising the supervisors: a case-based group forum for faculty development. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):521–4.

Lord JA, Mourtzanos E, McLaren K, Murray SB, Kimmel RJ, Cowley DS. A peer mentoring group for junior clinician educators: four years’ experience. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):378–83.

Murray SB, Levy M, Lord J, McLaren K. Peer-facilitated reflection: a tool for continuing professional development for faculty. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(2):125–8.

Sexton JM, Lord JA, Brenner CJ, Curry CE, Shyn SI, Cowley DS. Peer mentoring process for psychiatry curriculum revision: lessons learned from the “Mod Squad”. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):436–40.

Shoemaker EZ, Myint MT, Joshi SV, Hilty DM. Low-resource project-based interprofessional development with psychiatry faculty. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(3):413–23.

Rosenbaum M, Ferguson K, Kreiter C, Johnson C. Using a peer evaluation system to assess faculty performance and competence. Fam Med. 2005;37:429–33.

Newman LR, Lown BA, Jones RN, Johansson A, Schwartzstein RM. Developing a peer assessment of lecturing instrument: lessons learned. Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1104–10.