Abstract

Outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in adulthood are sobering, and many individuals with autism fail to establish independence, graduate from college, or find meaningful work. At the same time, individuals with ASD are increasingly entering higher education environments. While this is exciting to see, it has also presented a variety of challenges. Institutions of higher education need to provide for a smooth transition and must be prepared to address the needs of students with academic accommodations, specialized adjustment programs, and individualized coaching/skill building. In order to be successful, adequate planning must take place and individualized supports must be provided. In this chapter, we will review what is known about the process of adaptation to college. In addition, we will review what supports are commonly needed for individuals with ASD and how some colleges are meeting these needs. We will also discuss the importance of transition planning, so that preparation for college is occurring many years before entrance, and so that individuals are equipped with the skills likely to make them successful and engaged college students.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Outcomes of Individuals with ASD

By almost any standard one could choose, the outcomes of adult individuals with autism are poor. While educational entitlement is a legal right for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD ), many individuals fall off a service delivery cliff in adulthood. With a paucity of options available for vocational training and few programs geared for people with ASD at the college level, many individuals fall through the cracks (Gerhardt & Lainer, 2011). When this lack of engagement is coupled with aging parents, finite economic resources, and social isolation, the results are sobering. Many individuals with ASD fail to continue to develop skills in adulthood, often because they are unable to find the settings and supports that match their needs.

The deficits associated with ASD are numerous and have been well documented (e.g., restrictive and repetitive movements, social deficits, and communication impairments; American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Cai & Richdale, 2016; Ravizza et al., 2013). These deficits pose many challenges in childhood but are mitigated by widespread availability of services and by intense and individualized intervention (Howard et al., 2014). The extent to which individuals with ASD are prepared for the challenges of adulthood with that intervention is questionable. Often, individuals with ASD remain dependent on low ratios of student-teacher attention that are not available in vocational settings. Work performance may not be adequate for competitive employment. For those who are capable of higher education learning, the options are limited and the supports are few.

In the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (Newman et al., 2011), it was reported that about 60% of youth with disabilities attempt postsecondary education. However, only 32% of those with ASD attended postsecondary education schools. The vast majority of individuals with ASD do not even attempt college. Given that individuals with ASD can be motivated to learn, these statistics are concerning.

Furthermore, 21% of individuals with ASD had no employment or education experiences after high school (Newman et al., 2011). Of these individuals, 80% were living at home with their parents. Additionally, 40% reported having no friends, raising worries about severe social isolation. From a mental health perspective, it seems that many individuals with ASD enter adulthood with few connections, little structure, and much less autonomy than adults with other disabilities.

Unemployment and underemployment are also grave concerns, as more than 50% of individuals with ASD do not have paid work after high school (Eaves & Ho, 2008; Howlin et al. 2014; Shattuck et al., 2012; Taylor & Seltzer, 2011). Of those who did work, most never achieved anything close to full-time status (Eaves & Ho, 2008; Taylor & Seltzer, 2011). Some may even only be able to obtain work in segregated settings such as sheltered workshops (Carter et al., 2012; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009). In addition to the quality of life and mental health consequences that unemployment and underemployment have on the individuals themselves, there are additional negative financial consequences for the families and for society (Järbrink et al., 2007; Krieger et al., 2012; Taylor & Seltzer, 2012). Whittenburg et al. (2019) analyzed employment outcomes for over 4,000 individuals with autism who were transition age and received some vocational rehabilitation services. Predictably, the authors found that as levels of education increased, so did employment rates and weekly wages. Adults with postsecondary education held the highest employment rate (i.e., 68.9%) and earned the highest weekly wage (i.e., $207.80). In terms of underemployment, none of the groups broken down by educational level reached full-time employment; however, those with postsecondary education worked more hours than any other group (i.e., 19.1 h). Comparatively, those who finished high school worked an average of 14.3 h per week and earned $129.08 per week. Hence, these data are concerning from a societal perspective as well as from a humanitarian perspective.

Much has been done to understand how individuals with ASD might be integrated more successfully into employment contexts (Dreaver et al., 2020). Some characteristics of workers with ASD that have been commonly noted as valuable include attention to detail, task focus, passion, loyalty, and dependability (Dreaver et al., 2020). The match between the individual and the job seems to be of central importance. In addition, external supports have been noted as helping individuals to master socially relevant work skills (e.g., personal care, boundaries with others; Dreaver et al., 2020). In addition, adaptive strategies can assist the worker in successfully navigating the demands of the job. For example, the worker may be given strategies to mitigate sensory elements of the environment and to create daily routines for assigned tasks. Other supports that have been suggested include regular check-ins with supervisors, autism training for supervisors, and access to an expert for circumstances requiring more support and problem-solving (Dreaver et al., 2020). In a similar vein, speculation has been made about how to prepare individuals with ASD for college and how to support them once they are there.

In this chapter, we will review the enrollment characteristics of individuals with ASD who pursue higher education, their needs, the supports that are commonly available, and strategies for success. We will also review some program elements that are unique and some special challenges. We will also discuss best practices and areas for future research and program development.

Enrollment Characteristics of People with ASD in Institutions of Higher Education

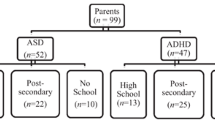

Many individuals with autism will seek out higher education following the completion of their high school programs. Continued study in a specialized degree may even be appealing for some individuals with autism (compared with high school), as college study allows for a more singularly focused educational experience that aligns with one of the core diagnostic features of autism: restricted areas of interest (Bakker et al., 2019; Viezel et al., 2020). There have been a number of identified predictors for participation in secondary education within the autism community. Chiang et al. (2012) identified family characteristics (e.g., parental expectations, household income), student characteristics (e.g., attending a general education high school, performing at grade level), and the ability to have in-depth transition planning (e.g., including the goal of higher education during transition planning with the student) as predictive of a successful enrollment in secondary education. Seemingly, parental involvement may play the largest role in promoting or inhibiting college success. This could be in the form of support, help, motivation, or even in the setting of expectations (Accardo, 2017).

In a large-scale study of individuals in the United Kingdom, there were a number of interesting disparities between the higher education enrollment characteristics of individuals with ASD and those without (Karola et al., 2016). The rate of individuals with autism who enrolled in higher education was 9–22%, compared to 45% of those without autism. Students with autism were generally younger than those without, and there was a significantly higher proportion of males to females with autism (i.e., a 4:1 ratio) compared to those without autism (i.e., a 1:1 ratio; Karola et al., 2016). There were also identified patterns related to subject choice for those with autism compared to those without. Students with autism were most likely to study computer science, creative arts and design, historical and philosophical studies, and mass communications and less likely to study medicine and dentistry and allied medicine (Karola et al., 2016). In a much smaller sample of 21 individuals and their families from Michigan, all participants (i.e., parents and individuals with autism) rated that they were confident they would attend postsecondary education (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009). There was a discrepancy between what the mothers of individuals with autism aspired for and their child’s or the father’s aspirations. Of the interviewed mothers, 45% reported that a vocational or associate degree was most likely; however, 55% said that a 4-year degree would be the goal. One mother phrased her aspirations for her child as “in my dreams … I have no idea whether or not this is realistic” (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009, p. 7).

Many individuals with autism seek out postsecondary education for the same reasons as their neurotypical peers. Most importantly, they seek higher education in order to gain access to increased job opportunities or in order to join a specific profession that requires a college education (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009). However, some individuals have also reported that they hope to seek out new friendships and a more independent lifestyle, either living with friends, a roommate, or on their own (Anderson et al., 2016). One high school student reported feeling that college students were less judgmental and that it would be easier to make friends on a campus setting than it had been in high school. Anderson et al. (2016) also found a perceived notion that friendships formed in a college setting were lifelong in comparison to friendships formed in high school. Additionally, many young adults with autism identify a goal for their college experience to be joining social clubs or organizations (Accardo, 2017; Anderson et al., 2016). Some even view that trying new things is part of what makes a successful college experience (Accardo, 2017).

Despite the increase in enrollment over time by students with autism, these students are also at the highest risk of dropping out and failing to complete their college degree. A 2015 study showed that the retention rate for students with a disability is approximately 53% compared to 64% for students without a disability (Sayman, 2015). Barnard-Brak et al. (2010) found that one reason for this disparity could be due to a lack of understanding on the part of faculty and administration of the diverse needs of students with a disability. Students with autism may also be less likely to seek out services to support their needs or may seek these services too late in their college tenure. This critical behavior is vastly different from what is available and provided in primary and secondary schools, where progress is monitored and requests for assistance are solicited. Unlike special education services in elementary and high school, higher education institutions are not required to seek out, identify, and support students with disabilities in the same way (Barnard-Brak et al., 2010).

Many individuals with ASD now seek college experiences, and many are capable of doing so with appropriate accommodations and individualized, embedded supports (Jansen et al., 2017). Given the stark data on outcomes in terms of independence and employment, increasing success in college is an important strategy to build additional career paths. In order to make the college environment more accessible, a variety of needs must be assessed, and individualized supports must be provided.

Needs of Individuals with ASD in Institutions of Higher Education

The issues for individuals with ASD in higher education settings are numerous and are varied. As the rate of postsecondary enrollment for ASD adults continues to rise (Newman et al., 2011), so does the call to address the needs and challenges these students face when joining the historically unchanging climate of higher academia. In some ways, the needs are different from those with other disabilities. As is often the case in autism, strengths of the learners can obscure deficits. Furthermore, the tendency to avoid communicating can be more prominent among this group of students. This makes it difficult to identify needs early in the semester, and it can make it difficult to create a success plan while the class/semester is still salvageable.

The other issue that makes campus life challenging for individuals with ASD is that the major challenges often lie outside of the classroom. While some of these students present as well qualified and capable of meeting the academic demands, just over half of these students are graduating (Sayman, 2015). Clearly, a variety of factors contribute to this statistic.

Even strong high school students often flounder with the transition to college (Anderson et al., 2018, 2020). While the academic demands may not represent a large cognitive leap, there is also often far less structure and support in the assignment of tasks. In college, professors expect students to read the syllabus, track due dates, and proactively reach out when they need assistance. Beyond academics, the expectations for independent living are also daunting. It is not uncommon for individuals with ASD to struggle the most with campus navigation, time and task management, emotional regulation, and social relationship navigation (Grogan, 2015). There may be a variety of social situations that the student was not expecting or is unable to navigate independently. Students may feel isolated if they do not easily make friends and do not have the comfort of living with people who support them (i.e., parents and siblings).

Arguably, one of the most anticipated aspects of the postsecondary experience for new college students is the freedom and flexibility of their schedule. Many college students relish the ability to organize their extracurricular activities around their course load and vice versa, often making modifications with each new semester. However, for a student with autism, this can mean the difference between maturation and attrition.

Case Example

-

Joshua is 18 years old and is a high school senior and will be a freshman at a local state college in the fall. He has done well with individualized attention in high school and took honors classes. He is more than capable of college level work. Still, his parents are worried. He has never lived away from home . They plan to get him a private room, since his schedule and behavior might irritate a roommate. His parents are worried about his ability to wake up independently on time, his tendency to procrastinate, and his social isolation. They notified the college counselor of these worries and were assured he will be on their radar, but they are not sure it will be enough.

Coming from the structured and predictable nature of the typical high school setting, the type of time and task management skills required at the collegiate level can be a challenging transition for students. The lack of structure in college settings compared to K–12 settings can be problematic during the transition period and can be noticeably lacking in family involvement. Additionally, K–12 settings have fewer academic stressors and can be less socially isolating than college settings (Cai & Richdale, 2016).

In contrast, this unstructured new reality, coupled with the inflexible style of teaching and learning that is common at many institutions, leads to increased difficulty with task completion and time management (Grogan, 2015). Anderson et al. (2020) surveyed 102 college students with autism in Australia and New Zealand and found that one of the most common self-reported concerns at the postsecondary level was the completion of academic tasks. To illustrate, students report struggling with understanding the syllabus and determining which details are most important, navigating the ambiguity of course assignments, and adjusting to the classical teaching and evaluation methods being implemented (Jansen et al., 2017). Even if the syllabus and assignments are understood, students with autism have indicated having a hard time planning out their studies and being able to gauge how much time should be spent on short- and long-term assignments in each course throughout the semester due to the lack of structure and routine (Fabri et al., 2016).

In addition to the grave challenges associated with time and task management, students with autism may find it more difficult to navigate the college campus itself (Longtin, 2014). Although some postsecondary settings have a new student orientation geared at helping incoming students get their bearings as they enter a new setting, it falls short of meeting the needs of ASD students. For example, many new student orientations can include sensory-heavy activities (e.g., band or cheer performances, returning students cheering on new students), which can be extremely aversive and even intolerable for sensory-sensitive individuals with autism. Additionally, these sensory sensitivities can continue to be a stressor for students throughout their duration of study, making general campus navigation a daring feat (Anderson et al., 2018). All considered, one of the biggest reasons why campus navigation can be an arduous task is because of the absent or inadequate transition planning.

Bakker et al. (2019) evaluated the retention of first-year students with ASD in higher education settings by surveying 96 students with autism, 2252 students with other disabilities, and 25,000 students without autism enrolled at a major university. Results showed that one of the areas of need indicated for students with autism was more robust transition planning. One suggestion made was that ASD students visit the college campus they have chosen to attend a few times prior to the start of classes to gain better familiarity with its layout and locations on campus that might be more sensory friendly. Furthermore, it would be helpful to obtain information for various on-campus services (e.g., health center, disability services) prior to the start of the semester, as well as a decision tree to help determine if and when contact with each service may be needed. Without adequate transitioning, students seem to have a more difficult time adjusting to changes in routine, classes, and location of services around campus (Cai & Richdale, 2016).

Emotional regulation among individuals with autism is also a serious concern, as they have been reported to have higher rates of comorbidity and emotional dysregulation than both neurotypical peers and peers with other disabilities (Bakker et al., 2019; Dijkhuis et al., 2020). Difficulties with emotional regulation are often coupled with heightened stress, fewer social supports, and barriers to the utilization of parental support compared to high school settings (Cai & Richdale, 2016; Dijkhuis et al., 2020). Some common emotional concerns include increased feelings of loneliness and isolation, higher stress levels, mood disorders, and suicidal ideation and attempts (Van Hees et al., 2015).

Case Example

-

Matt is 20 and is a sophomore at a private, small college. He is doing well academically but has hit some rough spots socially. Last semester, he received poor grades from a teacher and was very angry. He had some heated email exchanges with the professor and then decided to meet her in the parking lot as she headed home. In this interaction, he continued to make his same points and was very repetitive and insistent. The teacher later filed a complaint that she felt threatened, and the student is now being sent to a disciplinary hearing. The family is concerned, as there was already a complaint from a student who felt “stalked” when she refused the romantic interest expressed by Matt. He continued to sit near her in the cafeteria, and she often saw him near her, staring at her on campus. The campus police are concerned for the safety of other students and faculty and have issued stern warnings to Matt. Matt is becoming increasingly despondent about the issues, especially the police involvement, and has become more withdrawn.

Jackson et al. (2018) designed a cross-sectional study to better understand their range of postsecondary experiences; fifty-six college students with ASD were surveyed to gather insight regarding their academic, mental health, and social needs and experiences. Mental health experiences of interest included history of mental health diagnoses, past or present suicidal behavior, medication history, and symptoms related to anxiety, depression, or stress. More than half of all participants endorsed having a co-occurring diagnosis and taking at least one prescribed medication (Jackson et al., 2018). The mood diagnoses most commonly disclosed included various types of anxiety disorders (i.e., 60.7%), depression (i.e., 35.7%), bipolar disorder (i.e., 5.4%), and panic disorder (i.e., 1.8%). Jackson et al. (2018) concluded that comfort with academic coursework and feelings of loneliness were the two most statistically significant predictors of emotional distress and comorbidity with these mood disorders (Jackson et al., 2018).

Alarmingly, nearly 75% of participants also reported suicidal behavior (i.e., plan, ideation, attempt) in their lifetime, with more than half of the total sample endorsing suicidal ideation within the past year (Jackson et al., 2018). Statistically significant variables associated with increased suicidal behavior were the number of friends, level of academic comfort, reported loneliness, stress, and anxiety-related and depressive symptoms (Jackson et al., 2018). Similar findings were also reported in a 2020 study by Anderson and colleagues assessing the needs and characteristics of university students with autism in Australia. In their survey of 102 students, Anderson et al. (2020) found that students on the autism spectrum presented with significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation and self-harm than their neurotypical peers. Furthermore, Anderson and colleagues indicated that emotionally distressed students were likely not aware of available supports, did not feel available supports met their needs, and demonstrated poor advocacy skills that could potentially help them access novel ones (Anderson et al., 2020).

Case Example

-

Deandra is a 21-year-old college student who is exceptionally alone. She has tried to join a variety of clubs and activities, but none have resulted in meaningful connections. While she has some “friends” who say hello to her and greet her, she is never invited to meals or to parties. Over time, she has tried less and become more isolated. She now does lots of ordering food in, joining classes synchronously from her room, and letting assignments slide. Her roommates rarely see her, and she is failing a couple of classes.

Some mediators for emotional dysregulation are social support and feelings of connectedness. However, for individuals with autism, a diagnosis characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, this can present a unique and grueling challenge. While social support and a sense of belonging have been identified as protective factors for college retention and emotional regulation among ASD students (Karola et al., 2016), they report having a difficult time forming and maintaining the social connections necessary for these relationships (Braxton & McClendon, 2001; Dijkhuis et al., 2020). For instance, students must contend with the expectations of a new social landscape and set of social rules, as they are expected to be able to communicate effectively with peers and superiors without support. They are essentially required to learn how to navigate multiple social circles simultaneously; they struggle with picking up on the social cues of their classmates and teachers, connecting with classmates, participating in course discussions, and even knowing when and how to ask questions in class – a problem some refer to as limited interpersonal competence (Dijkhuis et al., 2020; Fabri et al., 2016; Van Hees et al., 2015). Van Hees et al. (2015) corroborated these findings in a study of 23 adults with autism currently enrolled in college. Based on information gathered from participants, results showed that 75% of students felt socially disconnected from their peers on campus, resulting in feelings of loneliness and isolation.

While each of these needs presents its own challenges to students, it is important to keep in mind that many individuals with autism in postsecondary settings are struggling to maneuver these needs simultaneously. Moreover, the needs and outcomes of each often affect the others. For instance, individuals with fewer social supports and emotional regulation skills are more likely to present with poorer time and task management skills. Conversely, poorer academic performance as a result of poor management skills can also exacerbate socioemotional needs. If students are not well equipped or informed enough to seek out the campus support they need, then there is a chance they will soon become a part of the ever-growing attrition statistics.

Commonly Available Supports and Services

The reality of college-based accommodations is that they are starkly different than the educational supports individuals with autism experience in primary and secondary school. Students are no longer protected under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), and as such, institutions of higher education are not required to ensure that students have the accommodations needed to be successful. This change in support level can often leave students feeling that they are not receiving all of the support they need. However, there are a number of colleges that have specific programs designed to support students with autism (Viezel et al., 2020), and all colleges that accept students with autism who receive federal financial aid must provide reasonable accommodations and support (Scheef et al., 2019). Thus, more supports are available than one might realize, and it is important to express and advocate for the accommodations that the student requires (Welkowitz & Baker, 2005).

Academic accommodations are commonly available for individuals with disabilities and can include extended deadlines, extra time on exams, provision of lecture notes, separate testing locations, tutors, detailed syllabi with concrete language, and curriculum/coursework modifications. In some cases, a scribe may accompany the learner to take notes. The goal of an academic accommodation is to allow the student to complete the assignment in a manner in which they are most comfortable (Gelbar et al., 2014). A successful accommodation should be paired to the student’s skill deficit. For example, Jansen et al. (2017) found that extended deadlines were most frequently used to combat difficulty with flexibility and were used to address global information processing deficits. For students who may take longer with all elements of coursework, such extensions can be very helpful. Jansen et al. also found that the most common accommodation was extended time for tests, and this was described by the students interviewed to be their most highly valued and needed accommodation. This pool of students also indicated that taking exams in a separate location or in a smaller group helped to reduce their stress levels and allowed for more cohesive planning and organizing for exams (Jansen et al., 2017). Academic supports are commonly given and are rated as useful by students with ASD, although more work is needed to specifically identify the most effective strategies and components (Anderson et al., 2019).

Social support services are also provided at the collegiate level. The most frequently reported social supports include supervised social activities, social skills groups, and housing accommodations (Accardo et al., 2019). Supervised social activities can help to bridge the gap and allow students with autism to meet other students with autism as well as forge connections with their peers. One of the sensitive issues in this context is disclosure. Accessing these services necessitates disclosure. This is a highly sensitive and individualized issue. Some individuals may wish to disclose this, and others may feel uncomfortable about it. It is important to note that the individual with ASD must have agency around this decision.

At times, social experiences are also combined with skills training, especially for complex chains of behavior that are necessary on the campus. Supervised social activities could include lunchtime socials, off-campus dinners, taking public transportation into a city, or attending a concert. Social skills groups are also commonly available and can either be therapeutic or nontherapeutic (Barnhill, 2016).

Case Example

-

Deandra could benefit immensely from a support opportunity like this. She could meet other students who have similar interests, and she would be able to forge meaningful connections through repeated encounters with them at the activities. There would also be a safe place for her to connect with others without leaving her in a vulnerable situation.

One of the biggest transitions for any student is living away from home in a campus setting. Some universities offer a college campus transition program, which allows for students to move into their dorms or university housing anywhere from 3 days to 6 weeks earlier than the rest of the student body. In some programs, this may be done as a summer program a year before entering college as well. For students who arrive early for this special pre-orientation, additional time on campus is spent attending presentations and workshops in order to get oriented to campus life (Accardo et al., 2019; Barnhill, 2016). In a 2019 survey of 23 students with autism who attended a mid-size university, the on-campus transition program was the most preferred support service following academic coaching (Accardo et al., 2019).

In addition to the physical location change of living on campus instead of at home, the expectations of independent living can be overwhelming for students. In a survey of 30 colleges, 80% offered instruction in life skills including laundry, budgeting, and hygiene (Barnhill, 2016). Some institutions of higher education make this a focus during summer intensive orientation programs. In addition to getting to know the campus and attending seminars, there are often lessons in laundry and time management, as these are aspects of independent living that may need more focus (Barnhill, 2016). Even simple tasks such as waking for class might be a new transition for a student who has been woken each morning for high school by their parents.

Counseling services are commonly available to students whose struggles intensify and exceed the social interventions available through residence life initiatives (Francis & Horn, 2017). When individual counseling is needed, it is important to facilitate engagement with the counseling center staff. Both individual and group counseling can help identify areas of need and can assist in developing a plan to address the most pressing concerns. Furthermore, individual counseling allows for the ongoing assessment of the most worrisome symptoms, such as suicidal ideation, lack of initiative, and isolation from the college community.

Case Example

-

Deandra is in need of assessment and treatment from the counseling center and will likely require continued care to assess and address the intensity of her depression. Weekly goals regarding engagement might help her reverse the course of her current path, and support may help her access other resources.

-

Matt also could benefit from the counseling center, as he learns to inhibit some of the behaviors that others are finding frightening. Evidence-based strategies could be used to identify appropriate and inappropriate responses and interactions, and the therapist could rehearse more appropriate responses to stressful situations.

Supports Needed but Not Commonly Available

Accardo et al. (2019) interviewed students with autism about what supports they felt they needed that were not provided or were not initially provided to them. One of the common themes was the general idea of not knowing what was available or what students would benefit from. One student interviewed suggested that during the start of the semester, students be provided with an initial consultation with a service center coordinator to explore what accommodations or supports would be beneficial. This ties into the idea that students would benefit from a more personalized approach to their postsecondary education (Accardo et al., 2019). Some students may also be unsure how to identify with their disability without someone coaching them, which can lead to the student being unaware of how to advocate for themselves.

Neurotypical students may also dread the details of registration and course planning. In most colleges, this is associated with anxiety, and there is often a perception of urgent competition for available courses. One must be “ready,” having organized options and being able to speedily navigate course registration sites at the time of registration. For individuals with ASD, a common complaint was the ability to plan better at the time of course registration (Accardo et al., 2019). Students indicated that having access to the professors’ office hours would influence their decisions about what courses to take based on how it would fit into their academic schedule (Accardo et al., 2019). Students with disabilities are often encouraged to attend office hours to discuss any difficulties they are having with the course or reach out for any extra help that may be available to them. Better outcomes (e.g., better grades, higher retention rates) have been demonstrated to have a correlational relationship with increased communication with faculty (Austin & Peña, 2017). Willey (2000) suggested that students plan realistically when completing their course registration and cautioned against planning back-to-back classes that were not in the same building and not scheduling courses that were outside of the student’s typical schedule (e.g., early mornings, late nights). It may be helpful for students to mark drop dates of courses, so as to avoid a negative impact on their grade point average.

During classes, many different issues may impact the student. Some of these are highly idiosyncratic, and some are more universal. In any case, the student must be aware of their own personal vulnerabilities and of the strategies that work best for them. Some requests might be able to be prophylactically made, to avoid negative outcomes. After the semester begins, if sudden changes in routine are upsetting, it may be helpful to ask the professor for advance warning for any changes in the schedule or assignment requirements (Willey, 2000). It may also be helpful to learn where and how the professor will post changes to expectations so that the student can know where to go to get the most up-to-date information about the course.

It is not uncommon for those new to college to seek a community. For an individual with special needs, access to such a community is even more essential. Supports that assist across learners with special needs include physical spaces that provide solace and structure. In an interview of 12 postsecondary students enrolled in a university program, one of the most common themes was a safe location space to meet during the day (Scheef et al., 2019). This is a support that may not be readily available at all universities. Students appreciated having a designated space to complete assignments where the distractions and environmental stimuli were minimal. Alternatively, students also found it helpful to have a designated space to meet with others and play board games or just have a useful social outlet (Scheef et al., 2019).

Strategies for Success

As the enrollment of college students with autism continues to grow, college faculty must continue to adapt and learn how to most effectively teach all students. Feeling supported by faculty members has been identified as a key component for student success, and transversely, students suffer when they feel they cannot seek out help or that a faculty have a reluctance to work with them (Herbert et al., 2014). Naturally, students will also experience an array of responsiveness from various faculty members who have their own history of working with students with disabilities (Herbert et al., 2014).

One framework for supportive faculty-student interactions is a pedagogical approach to responsive teaching, which includes structured scaffolding, differentiated instruction, comprehensive accommodations, and collaborative institutional support (Austin & Peña, 2017). Structured scaffolding has been demonstrated to be effective in helping students with autism. This approach involves taking larger assignments and breaking them down into smaller components with clearly outlined expectations (Austin & Peña, 2017). This method of instruction is credited for enhancing learner outcomes by increasing engagement with course material.

Differentiated instruction involves approaching content material through different methods and approaches such as lectures, discussions, small group projects, and interactive activities. This pedagogical approach allows for a multidimensional learning experience and enhances different learning styles. A responsive approach to differentiated instruction is one in which the professor acknowledges that it is their responsibility to teach the content, but there are many different ways in which this can be approached (Austin & Peña, 2017). This approach could also allow for students to self-select a modality of instruction that would benefit their studies. If the student was aware of their own learning style, they could request an accommodation through their professor for one modality over another.

The use of comprehensive accommodations should focus on the strengths of each individual student and the ways in which they are most capable of succeeding. This approach to education can be seen as “leveling the playing field” in order to give everyone access to an equal education (Austin & Peña, 2017). This does not mean compromising the rigor of the assignment, but rather it allows the student the support to complete the assignment in a way that is meaningful for them. For example, some students might have difficulty writing as a means to demonstrate their mastery of material. They may be permitted to present an uploaded audio file explaining the material. Similarly, a student may have difficulty in a class presentation, especially if comorbid anxiety is an additional diagnosis. Such students might be permitted to pre-record their class presentation and play it for the class.

The final pedagogical approach to responsive teaching is collaborative institutional support. A successful faculty member is often provided support themselves, either from the college’s disabilities office or other available avenues that support learners with disabilities (Austin & Peña, 2017). In this way, the instructor can be assisted to identify and implement supports and accommodations that improve the learner’s engagement and performance in the class.

While these should be recognized as a good foundational framework, faculty need to make sure that their behavior reflects confidence, understanding, and flexibility in working with students who have a learning or developmental disability. Cawthon & Cole (2010) surveyed 110 students and found only 32% of students indicated that they had interacted with their professors about their learning disability. Most concerningly, students reported a number of obstacles that they encountered when attempting to obtain accommodations or support services, and at the top of the list were professors who were unwilling to accommodate them or were hard to schedule time with (Cawthon & Cole, 2010).

Hsiao et al. (2019) developed a yearlong, five-module faculty development program that helps to create proficiency with working with students with disabilities. Module 1 focused on background information about legislation and support as well as accommodations and how to make environments physically welcoming. This module also highlighted departmental and campus-wide resources that are available for faculty members to access. Module 2 encompassed implications of laws and regulations, the roles and responsibilities of faculty members, students and disability support services, and the components of a reasonable accommodation. This module was led by the director of disability support services, which made this an individualized approach to each institution of higher education. Module 3 was a student panel that focused on characteristics of diverse learners and accommodation strategies. One of the highlighted features of this module is the suggestions provided by the student panel for how faculty members can create an inclusive classroom. Module 4 switched to an accessible online learning focus with a month-long online course delivered through the university’s learning management system. This module worked through how to create accessible online content for students with disabilities and highlighted resources available to faculty through the learning management system. Finally, Module 5 focused on celebrations, reflections, and moving forward in a focus group-based discussion.

Peer Mentors

Peer mentors in postsecondary education help to support individuals with developmental disabilities across many different domains including learning, working, and socializing. The peer mentoring process is when a mentor guides a mentee through a new role in a new setting by providing modeling, support, and guidance. A peer mentor should help support an individual to complete a task as independently as possible, meeting them at the level of assistance they require (Fisher et al., 2020. Peer mentoring programs also help students to increase their social skills and can make community participation more successful (Gibbons et al., 2018; Harrison et al., 2019). Additionally, these programs are a good model for other community members and may lead to decreased stigmatization and discrimination against people with disabilities (Athamanah et al., 2020; Izzo & Shuman, 2013).

One pedagogical approach for peer mentorship programs is to use a service-learning model. A service-learning approach integrates community service with academic instruction and focuses on personal and professional growth, development of a multicultural experience, and awareness of a multitude of social issues (Gibbons et al., 2018). Some peer mentorship programs offer college students course credit for completing a class on disabilities while mentoring individuals with developmental disabilities. Throughout the course of the semester, students would provide weekly contact with their mentees and could provide both academic and social support based on the need and level of support desired (Izzo & Shuman, 2013). This model has been demonstrated to be most effective when the academic course matches the population with whom the mentor works. Through the hands-on experience of peer mentoring, mentors have been able to engage in self-exploration, which in turn leads to professional and personal growth (Gibbons et al., 2018).

Specific Program Characteristics

There are currently 73 institutions of higher education (i.e., 2-year, 4-year, and secondary support programs) that offer individualized and group support services for individuals on the autism spectrum. Some of the programs are associated with a per semester fee, while others are at no cost to the individual (College Autism Spectrum, n.d.). Table 9.1 shows a summary of the types of services and supports that are provided at each of the 73 institutions of higher education referenced above.

Bridge Programs

A significant mediator for academic success among students with autism in postsecondary settings is proper transition planning (Shattuck et al., 2012; Van Hees et al., 2015). In an effort to close this gap, colleges and universities nationwide have begun to implement bridge programs specifically for students with autism. To illustrate, LeTourneau University (2020) in Texas provides students with a specialized new student orientation, weekly individual and group coaching, ongoing peer mentorship, liaison services to increase access to campus support services, and assistance with understanding campus culture. While this program does prioritize the support and matriculation of its students, it is important to note that participation requires students to pay an additional fee per semester and disclose their autism diagnosis – two factors that could present as barriers to entry for prospective students.

The Bridge to Independence program at Nicholls State University is the first of its kind to be certified in Louisiana by the US Department of Education. The focus of Nicholls’ program is to provide support to currently enrolled students with ASD and intellectual disabilities, including having designated peer mentors and academic coaches for students to assist with coursework completion, campus navigation, and social support. Other services include modifications and accommodations to course and diploma requirements, optional social skills seminars, ongoing student check-ins, and liaison support between students and other campus resources as needed (Nicholls State University, 2019).

Pathways , another college bridge program based at Illinois’ Aurora University, is unique in its comprehensiveness, as it offers bridge programs to current high school students, newly enrolled college students, and recent graduate students with autism (AU Magazine, 2020). These programs, each unique in their own right, are merely a snapshot of the numerous transition and support programs available to students nationwide. While the services and emphasis of each program differ from the next, they continue to grow in number and breadth. To date, there are 72 college-based bridge and support programs for students with autism across 32 states, in addition to countless college preparation programs offered by non-academic organizations (Brown, 2021).

Transitioning into Higher Education

Individuals with ASD face many challenges as they transition to adulthood. In almost all aspects of life (e.g., independent living, employment, higher education), outcomes are worrisome and can be improved. In many ways, the supports for adults with ASD are elusive. Some programs provide enhanced support, and these are associated with better outcomes.

The solutions, of course, need to be incorporated much earlier into the education of individuals with ASD. Now that more individuals with autism are attending college, the middle and high school years need to be used to focus more on the requisite skills (Gerhardt & Lainer, 2011). Programming to enhance life skills, time management, financial planning, long-term management skills, problem-solving skills, independent travel, and managing a schedule of competing demands independently should all be focused on in middle and high school education. The development of these skills in the high school years can ease the transition to college and program for success in college environments. Many of these skills are not needed in high school, when parents are proximal and independence is limited. Once in college, however, many skills will need to be available that were not necessary in younger years. This extension of transitional planning to include the possibility of higher education experiences should be incorporated as early as possible, as these skills will require years of shaping and development.

In a model of supports aligned for college-bound individuals with ASD, Chickering and Reisser (1969) created three vectors of support that describe how to best create a successful college-bound student. The first behavioral domain is to achieve competency in intellectual skills and expand interpersonal skills (e.g., working cooperatively to reach a goal). The second level is to manage emotions, which emphasizes how to express oneself appropriately no matter the situation. This domain includes self-control and should highlight the need to learn safe behavior, advocacy skills, and an understanding of sexual education. The final vector is moving through autonomy toward independence and should be focused on developing freedom and trusting their own abilities (Chickering & Reisser, 1969).

As with many other challenges associated with ASD, the solutions require coordinated planning, collaboration between instructions and families, and individualized goals (Chiang et al., 2012; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009). Once in college, the need for supports must be assessed so that individuals can be helped to succeed. A broad assessment of skills, including those associated with the navigation of the physical and social environments, is crucial. Ongoing check-ins can identify problems early in development so that proper support can be provided.

Disclosure (to Share or Not to Share)

Research has shown that an individual is less likely to request accommodations when they encounter a faculty member who has a misconception about support needs (Austin & Peña, 2017). In turn, these individuals are less likely to disclose to the faculty member that they have a disability and may need an accommodation (Black et al., 2015; Herbert et al., 2014; Noble & Childers, 2008; Park et al., 2012). This can be a barrier to success for students as they are unable to access the support they need. Additionally, some students may feel that disclosing they have a disability and accessing accommodations is an advantage over their peers. This can fuel the ongoing stigma of having a disability and being treated differently. In order to be viewed as the “same” as their peers, some students may be even more unlikely to disclose their disability to their professors (Squires et al., 2018). Many students have disclosed that they are “anxious for a new beginning” (Herbert et al., 2014, p. 24) and as a result do not choose to use disability services that are available to them.

Other students may feel the desire to challenge themselves and view college as an opportunity to grow and overcome their disability. Some students have reported that turning down accommodations that were provided to them (i.e., note taking and extended time on tests) would force them to advance their skills in these areas (Squires et al., 2018; Van Hees et al., 2015). Without having these services to support them, some learners indicate that they create better, more consistent study habits and are forced to learn better time management skills. Some students indicate that they were proud of themselves for working at the same pace or completing the same assignments as everyone else (Squires et al., 2018; Van Hees et al., 2015). This is certainly a theme throughout the journey of postsecondary education that students want to enhance their independence (Squires et al., 2018).

Family Impact on Success

When families stay involved and support a student through the transition and their continued collegiate life, the outcomes are more successful, and a student with ASD is more likely to be able to complete their degree (Van Hees et al., 2015). One of the key roles that a family member can play in the transition to higher education is to assess how the student adapts and handles different stressful situations or changes to their day-to-day routine (Dallas et al., 2015). While allowing the student to try to handle an issue independently, the family member can help create problem-solving ideas or suggestions to ease the burden of a difficult situation the next time one arises. This model allows the student to have independence while being a safety net of support in case the need arises.

A general theme for research conducted with families who have a student in higher education is to be a level of support that allows the student to be successful, while challenging them to be their own self-advocate and live as independent of a life as wanted (Dallas et al., 2015). Some of the supports that parents felt they could provide to their children could be viewed as more of a “behind-the-scenes” role and could involve tasks such as managing money, paying bills, and managing appointments (Morrison et al., 2009).

Another important factor to consider is the bidirectionality of the relationship between child and parent and what this means to each member of the relationship. For a neurotypical child that is transitioning to college, the relationship between parent and child changes. Some children will report that there is an increase in more “open” communication, feeling “equal” to their parents, and acquiring more independence (Van Hees et al., 2018). This can create complex emotions on the part of parents and children who want these aspirations but are unsure of how to navigate the transition. One area of particular difficulty is the parent’s ability to communicate with their child’s university, a practice that in primary and secondary education is second nature. Once their child enrolls in a university, there are privacy laws (i.e., transferring the education rights from parents to students) that can leave parents feeling powerless at times (Van Hees et al., 2018). It is important for families to know their rights under the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and to be able to make an informed decision regarding waivers for college faculty to be able to connect with parents (Francis et al., 2017).

One of the ways parents can conquer this feeling of helplessness is to help students become more self-determined. A shift in mindset from making decisions “for” to making decisions “with” is vital to helping students reach a greater mode of independence. This can be a learning experience for families as well, as they shift into the role of an advisor and help to support decision-making and allowing for their child to face the natural consequences of their actions (Francis et al., 2017).

Case Example

-

Joshua has trouble with getting up on time; in high school, his parents always set his alarm for him, and if he overslept, they would be there to prompt him to get up and start his day so he did not miss class. As his parents shifted into their new role of supporting and doing things “with” him, they talked to him about how he could have a new backup system that did not involve him. Joshua now has an alarm clock in his room, but he also sets reminders on his smartphone as well.

Availability of Sexual Education Programs

Approximately 58% of adults report being sexually active by the age of 18 years – a figure that jumps to 75% by the time most adults turn 20 years old (Uecker & Regnerus, 2010). While we do not have isolated data on the sexual activity of college students with autism, we can reliably assume that they are seeking to engage in physical relationships at a rate that is similar to their peers. Adults with autism report sexual interests and desires consistent with their neurotypical peers, supporting the need for ASD-informed sexual education programming. Even so, they are often stereotyped as uninterested or incapable of social connection or sexual desire (Schöttle et al., 2017).

Parents of adults with autism also struggle with the decision to sexually educate their children, having to reconcile the fact that their child may present with deficits in some aspects of development yet still have the capacity for mature sexual thoughts and desires (Ruble & Dalrymple, 1993). Moreover, many parents who do provide or intend to provide some form of sexual knowledge to their child question whether they are capable of grasping concepts beyond the biological functions of sex, namely, sexuality, sexual violence, and socially appropriate sexual behavior (Ballan, 2012). As a result, sexual education programs for individuals with autism are likely inadequate or nonexistent. This dearth of sexual education programs, combined with the novel postsecondary challenges previously discussed, can be calamitous for these students. In the next few sections, the implications of deficits in sexual knowledge will be addressed.

The culmination of a lack of exposure to proper sexual education, the social deficits characteristic of autism, and developmentally appropriate level of sexual interest place these individuals at higher risk for sexual victimization and perpetration. Specifically, adults on the spectrum are 2.4 times as likely to experience rape and three times more likely to receive other unwanted sexual advances than their neurotypical counterparts (Brown-Lavoie et al., 2014). Conversely, an increase in one’s sexual knowledge has been found to be a mediating factor relative to sexual victimization from others, reducing its risk of occurrence (Brown-Lavoie et al., 2014).

Sutton and colleagues (2013) conducted a pilot study surveying 37 incarcerated males and found that 60% met criteria for ASD, citing that the core deficits of ASD coupled with a limited sexual knowledge place these individuals at greater risk of engagement in socially unacceptable behavior. While these findings are not indicative of all males on the spectrum, it remains important to highlight the extent to which a lack of adequate sexual education information can severely impact an individual’s life.

Sexual education is typically taught retroactively, following an instance of inappropriate behavior, rather than as a preventative measure (Ford, 1987). Similarly, Loftin and Hartlage (2015) maintain that intensive sexual education programs addressing the unique needs of individuals with ASD are likely not accessible until an individual has been sexually victimized or has committed a sexual crime, most likely in error. Of the sexual education programs currently available, most emphasize the biological and anatomical perspective of sex but often neglect to stress the sociocultural norms consistent with a consensual, romantic relationship (McCarthy, 2020).

Intersectionality of ASD, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity

Historically, members of the LGBTQ+ community have been subjected to severe relentless discrimination and ostracism. LGBTQ+ membership alone is significantly correlated with higher rates of mental health diagnoses, increased disparities in access to healthcare and treatment, and chronically unmet or undertreatment health-related issues. When compounded with an autism diagnosis, the risk for mental health issues and disparities in adequate access to treatment is augmented (Duke, 2011; Hall et al., 2020).

Despite the fact that the literature available on the intersectionality of disability status and sexual orientation or gender identity is relatively nonexistent, recent studies have shown that individuals with ASD are more likely to identify with nonheterosexual and gender-fluid groups than their neurotypical counterparts (George & Stokes, 2018; Glidden et al., 2016). In an effort to better understand their unique experiences, Hillier et al. (2019) conducted a small focus group of adults with autism who identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community. What Hillier et al. gathered from this study was that the intersectionality of LGBTQ+ membership and an autism diagnosis means having to balance two historically oppressed dual identities, navigating multiple minority stressors, increased feelings of isolation, and decreased lack of appropriate services.

These findings highlight the urgent need to create sexual education programs that bring awareness to the distinctive experiences and unmet needs of this dually marginalized group both before and during their postsecondary experience. Gender diversity and healthy sexual functioning should likely be core aspects of the sexual education program, as both have repeatedly been identified as important aspects of psychosocial development. All considered, adequate programming must be relationship oriented and account for core ASD deficits in social interaction and theory of mind, as these skills are foundational in the individual’s ability to empathize, understand, and appropriately respond to their partner (Solomon et al., 2019). This should also include a discussion of examples and non-examples regarding when and where certain sexual behaviors are socially acceptable to engage in.

Conclusion

Individuals with ASD are increasingly entering higher education settings. This is encouraging, as it may help to improve the vocational outcomes for these individuals and may increase the chances that they will attain independent living. While many of these individuals have excelled in high school, many will require academic accommodations and strategies designed to support their engagement, productivity, and success. Most will require assistance in adapting to the higher level of independence associated with college. In addition, the social landscape will present novel challenges requiring instruction and support.

Colleges and universities can provide specialized services to these students before entering the setting, during orientation, and while enrolled. Some of the most important supports include structured social experiences, peer mentors, individual counseling, and skill building. Social experiences and peer mentors can reduce isolation and provide social contact that is supported and monitored. Individual counseling allows for continuous assessment of student adaptation, identification of intense needs, and access to professionally mediated problem-solving and social support. Skill building can be done in individual sessions or in group contexts and can ensure that comprehensive attention is given to college-relevant (e.g., time management), social (e.g., communication), and safety (e.g., assertiveness, limit setting, harm reduction) skills.

Special attention must be paid to issues regarding complex social contexts such as dating and sexuality. Emotional regulation skills are also essential to success, as difficulties in this area can lead to negative consequences and social avoidance by others. It is essential that these complex, hidden skills are also targeted for intervention and that individuals are broadly assessed to ensure that these issues are not missed.

It is exciting to see so many individuals with ASD entering higher education settings and to help so many of them realize their potential in this environment. Preparing the faculty and staff to meet the unique needs of these learners is essential to success. Training will ensure that the environment provides scaffolded supports to reduce stress for the students and that faculty are assisted to understand and provide the necessary supports. With careful planning, individualized assessment, and creative supports, these students can thrive and succeed.

References

Accardo, A. L. (2017). College-bound young adults with ASD: Self-reported factors promoting and inhibiting success. College of Education Faculty Scholarship, 9, 36–46.

Accardo, A. L., Kuder, S. J., & Woodruff, J. (2019). Accommodations and support services preferred by college students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318760490

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Anderson, K. A., McDonald, T. A., Edsall, D., Smith, L. E., & Lounds Taylor, J. (2016). Postsecondary expectations of high school students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615610107

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2018). Perspectives of university students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3257-3

Anderson, A., Stephenson, J., Carter, M., & Carlon, S. (2019). A systematic literature review of empirical research on postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 1531–1558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3840-2

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2020). An on-line survey of university students with autism spectrum disorder in Australia and New Zealand: characteristics, support satisfaction, and advocacy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04259-8

Athamanah, L. S., Fisher, M. H., Sung, C., & Han, J. E. (2020). The experiences and perceptions of college peer mentors interacting with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45(4), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796920953826

AU Magazine. (2020). The bridge to hope: Helping students with autism find their path to college and beyond. Aurora University. https://aurora.edu/pathways/bridge-to-hope.html

Austin, K. S., & Peña, E. V. (2017). Exceptional faculty members who responsively teach students with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 30(1), 17–32.

Bakker, T., Krabbendamm, L., Bhulai, S., & Begeer, S. (2019). Background and enrollment characteristics of students with autism in higher education. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 67, 101424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101424

Ballan, M. S. (2012). Parental perspectives of communication about sexuality in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(5), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1293-y

Barnard-Brak, L., Lechtenberger, D. A., & Lan, W. Y. (2010). Accommodation strategies of college students with disabilities. Qualitative Report, 15(2), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1158

Barnhill, G. P. (2016). Supporting students with Asperger syndrome on college campuses: Current practices. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614523121

Black, D. R., Weinberg, L. A., & Brodwin, M. G. (2015). Universal design for learning and instruction: Perspectives of students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptionality Education International, 25(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v25i2.7723

Braxton, J. M., & McClendon, S. A. (2001). The fostering of social integration and retention through institutional practice. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 3(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.2190/RGXJ-U08C-06VB-JK7D

Brown, J. (2021). College programs. College Autism Spectrum. https://collegeautismspectrum.com/collegeprograms/

Brown-Lavoie, S. M., Viecili, M. A., & Weiss, J. A. (2014). Sexual knowledge and victimization in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2185–2196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2093-y

Cai, R. Y., & Richdale, A. L. (2016). Educational experiences and needs of higher education students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2535-1

Camarena, P. M., & Sarigiani, P. A. (2009). Postsecondary educational aspirations of high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and their parents. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609332675

Carter, E. W., Austin, D., & Trainor, A. A. (2012). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23, 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311414680

Cawthon, S. W., & Cole, E. V. (2010). Secondary students who have a learning disability: Student perspectives on accommodations access and obstacles. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 23(2), 112–128.

Chiang, H. M., Cheung, Y. K., Hickson, L., Xiang, R., & Tsai, L. Y. (2012). Predictive factors of participation in postsecondary education for high school leavers with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(5), 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1297-7

Chickering, A. W., & Reisser, L. (1969). Education and identity (2nd ed.). Jossey- Bass.

College Autism Spectrum. (n.d.). College programs. https://collegeautismspectrum.com/collegeprograms/

Dallas, B. K., Ramisch, J. L., & McGowan, B. (2015). Students with autism spectrum disorder and the role of family in postsecondary settings: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 2(8), 135–147.

Dijkhuis, R. R., de Sonneville, L., Ziermans, T. B., Staal, W. G., & Swaab, H. (2020). Autism symptoms, executive functioning and academic progress in higher education students. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(4), 1353–1363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04267-8

Dreaver, J., Thompson, C., Girdler, S., Adolfsson, M., Black, M. H., & Falkmer, M. (2020). Success factors enabling employment for adults on the autism spectrum from employers’ perspective. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(5), 1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03923-3

Duke, T. S. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth with disabilities: A meta synthesis. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(1), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.519181

Eaves, L. C., & Ho, H. H. (2008). Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 739–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x

Fabri, M., Andrews, P., & Pukki, H. (2016). A guide to best practice in supporting higher education students on the autism spectrum—for professionals within and outside of HE. Autism & Uni- Widening Access to Higher Education for Students on the Autism Spectrum, 28, 1–28.

Fisher, M. H., Athamanah, L. S., Sung, C., & Josol, C. K. (2020). Applying the self-determination theory to develop a school-to-work peer mentoring programme to promote social inclusion. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(2), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12673

Ford, A. (1987). Sex education for individuals with autism: Structuring information and opportunities. In D. Cohen & A. Donnellan (Eds.), Handbook of autism and developmental disorders (pp. 430–439). Wiley.

Francis, P. C., & Horn, A. C. (2017). Mental health services and counseling services in higher education: An overview of recent research and recommended practices. Higher Education Policy, 30(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0036-2

Francis, G. L., Duke, J. M., & Chiu, C. (2017). The college road trip: Supporting college success for students with autism. Division of Autism and Developmental Disabilities Online Journal, 4(1), 20–35.

Gelbar, N. W., Smith, I., & Reichow, B. (2014). Systematic review of articles describing experience and supports of individuals with autism enrolled in college and university programs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2593–2601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5

George, R., & Stokes, M. A. (2018). Gender identity and sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 22(8), 970–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317714587

Gerhardt, P. F., & Lainer, I. (2011). Addressing the needs of adolescents and adults with autism: A crisis on the horizon. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 41, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-010-9160-2

Gibbons, M., Taylor, A. L., Wheat, L. S., & Szepe, A. (2018). Transformative learning for peer mentors connected to a postsecondary education program for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Research on Service- Learning and Community Engagement, 6(1), 1–13.

Glidden, D., Bouman, W. P., Jones, B. A., & Arcelus, J. (2016). Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 4(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2015.10.003

Grogan, G. (2015). Supporting students with autism in higher education through teacher educator programs. SRATE Journal, 24(2), 8–13.

Hall, J. P., Batza, K., Streed, C. G., Jr., Boyd, B. A., & Kurth, N. K. (2020). Health disparities among sexual and gender minorities with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(8), 3071–3077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04399-2

Harrison, A. J., Bisson, J. B., & Laws, C. B. (2019). Impact of an inclusive postsecondary education program on implicit and explicit attitudes toward intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-57.4.323

Hendricks, D. R., & Wehman, P. (2009). Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357608329827

Herbert, J. T., Hong, B. S., Byun, S. Y., Welsh, W., Kurz, C. A., & Atkinson, H. A. (2014). Persistence and graduation of college students seeking disability support services. Journal of Rehabilitation, 80(1), 22–32.

Hillier, A., Gallop, N., Mendes, E., Tellez, D., Buckingham, A., Nizami, A., & OToole, D. (2019). LGBTQ + and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1594484

Howard, J. S., Stanislaw, H., Green, G., Sparkman, C. R., & Cohen, H. G. (2014). Comparison of behavior analytic and eclectic early interventions for young children with autism after three years. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(12), 3326–3334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.021

Howlin, P., Savage, S., Moss, P., Tempier, A., & Rutter, M. (2014). Cognitive and language skills in adults with autism: A 40-year-follow-up. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12115

Hsiao, F., Burgstahler, S., Nuss, D., & Doherty, M. (2019). Promoting an accessible learning environment for students with disabilities via faculty development (Practice brief). Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 32(1), 91–99.

Individuals with Disabilities Education and Improvement Act. (2004). 20 U.S.C §1400.

Izzo, M. V., & Shuman, A. (2013). Impact of inclusive college programs serving students with intellectual disabilities on disability studies interns and typically enrolled students. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26(4), 321–335.

Jackson, S., Hart, L., Brown, J. T., & Volkmar, F. R. (2018). Brief report: Self-reported academic, social, and mental health experiences of post-secondary students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3315-x

Jansen, D., Petry, K., Ceulemans, E., Noens, I., & Baeyens, D. (2017). Functioning and participation problems of students with ASD in higher education: Which reasonable accommodations are effective? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254962

Järbrink, K., McCrone, P., Fombonne, E., Zandén, H., & Knapp, M. (2007). Cost-impact of young adults with high functioning autistic spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(1), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2005.11.002

Karola, D., Julie-Ann, J., & Lyn, M. (2016). School’s out forever: Postsecondary educational trajectories of students with autism. Australian Psychologist, 51(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12228

Krieger, B., Kinébanian, A., Prodinger, B., & Heigl, F. (2012). Becoming a member of the work force: Perceptions of adults with Asperger Syndrome. Work, 43(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-1392

LeTourneau University. (2020). Bridges College Success Program: Academic & social support for student with autism. LeTourneau University. https://www.letu.edu/student-life/bridges-program.html

Loftin, R. L., & Hartlage, A. S. (2015). Sex education, sexual health, and autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics and Therapeutics, 5(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0665.1000230

Longtin, S. E. (2014). Using the college infrastructure to support students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(1), 63–72.

McCarthy, A. (2020, February 14). CRUSH: Developing a sexual education program for young adults on the autism spectrum. Boston Children’s Hospital.. https://answers.childrenshospital.org/crush-developing-a-sexual-education-program-for-young-adults-on-the-autism-spectrum/

Morrison, J. Q., Sansosti, F. J., & Hadley, W. M. (2009). Parent perceptions of the anticipated needs and expectations for support for their college- bound children with Asperger’s Syndrome. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 22(2), 78–87.

Newman, L., Wagner, M., Knockey, A. M., Marder, C., Nagle, K., Shaver, D., & Wei, X. (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school: A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study – 2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011–3005. National Center for Special Education Research.

Nicholls State University. (2019). Bridge to independence. Nicholls State University. https://www.nicholls.edu/education/support-programs/bridge-to-independence/

Noble, K. D., & Childers, S. A. (2008). A passion for learning: The theory and practice of Optima Match at the University of Washington. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19(20), 236–270. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-774