Abstract

The year 2020 was marked as the year in which the Covid-19 pandemic broke out. A pandemic of health origin of great proportion worldwide and that generated impacts in all segments, be they health, economic, social and organizational. The Human Resources Management (HRM) Department of the companies was called upon to act strongly in the elaboration of strategies of the human resources processes to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic on the preservation of workers’ health, identification of the possibilities of adjustments in processes and activities of people management, and for the continuity of work activities. This study aims to identify how the organizations’ human resources department was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic for the continuity of carrying out people management processes, with a comparison between HRM practices in Brazil and Portugal. The interpretative paradigm was the methodological assumption used, with a qualitative methodology. Interviews were conducted with HRM professionals from Brazilian and Portuguese companies. This study confirms that the HRM of the interviewed companies in Brazil and Portugal was strongly impacted by the restrictions caused by the pandemic in people’s management. These impacts were many and of different orders. They range from systems and processes to mental illness. To deal with the new situations that arise from this scenario, HRM must rely on the resilience, wisdom and humanization that some interviewees referred to as lessons to be learned from the pandemic.

Delfina Gomes has conducted the study at Research Center in Political Science (UIDB/CPO/00758/2020), University of Minho/University of Évora and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science through national funds.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Covid-19 was declared a world pandemic by the WHO on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020). It is a transversal, global and universal problem that had consequences at all levels, namely at the health level, in which it generated a high number of deaths and possible health consequences, at the psychological and emotional level. It brought, beyond health issues, consequences at the political, economic, social, cultural level, among others, and varied impacts on people’s lifestyles. Focusing on the labor impact, this chapter intends to contribute to the identification of the changes and adaptations that the Human Resources Management (HRM) developed in companies in Brazil and Portugal.

The differences between Brazil and Portugal in the treatment of issues related to the Covid-19 pandemic and the political and economic decisions that were adopted at each stage during the evolution of the pandemic, had an immediate impact on the decisions that companies in each country took in safeguarding workers’ health, in business strategy and in maintaining productivity. These decisions by the companies were also influenced by “long and successive confinements [which] caused constraints in operations, forcing them to look for alternative ways to maintain their activity, either by reinventing their business models or redesigning their processes, but also investing in new technologies to support their business processes, collaboration and telework” (Samartinho & Barradas, 2020, p. 3). On the other hand, within this organizational context, the Human Resources Management department of the organizations was strongly asked to participate in these decisions. This study aims to identify how the organizations’ human resources department was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic for the continuity of carrying out people management processes, with a comparison between HRM practices in Brazil and Portugal. In particular, it is intended to analyze changes in recruitment and selection processes, in training systems, in the way work is organized, namely with the use of telework, and the impacts on organizational culture that may be related to the Covid-19 pandemic. It also aims to analyze the changes that have taken place in the routine of companies because they have proved to be an asset for companies, workers or both parties (Samartinho & Barradas, 2020).

With the pandemic situation and seeking to guarantee the health and safety of all organizational actors, there was a rethink in relation to the maintenance of jobs, the business strategy and the continuity of operations by the companies. Thus, every effort had an effect because “effectively, in a few days or weeks, organizations were able to adapt at various levels, from the way they manage their business, to the way they manage their facilities and human resources” (Samartinho & Barradas, 2020, p. 3).

There are three research questions, which relate to the general objective of this chapter:

-

1.

How have the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic altered some HRM practices in companies in Portugal and Brazil?

-

2.

What are the main facilitators and hindrances in terms of HRM adaptation in dealing with the effects of the pandemic at the labor level?

-

3.

What lessons can HRM learn from the crisis generated by Covid-19?

The research carried out is based on the interpretative paradigm, with the use of semi-structured interviews with managers of the HRM departments and a content analysis was carried out.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. The next section presents a review of the literature about the evolution of HRM, the Covid-19 pandemic and crisis management in organizations, as well as reactions in crisis situations. The methodology of the study and a description of the participants are presented in the subsequent section. Next, the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on HRM is analyzed, based on the perceptions of the interviewees. These perceptions and opinions are presented in three main dimensions, following the research questions of the study: how have the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic altered some HRM practices in companies in Portugal and Brazil; what are the main facilitators and hindrances in terms of HRM adaptation in dealing with the effects of the pandemic at the labor level; and, what lessons can HRM learn from the crisis generated by Covid-19. The final section offers a conclusion.

2 Literature Review

2.1 The Evolution of HRM: Some Theoretical Considerations

The current human resources management function has undergone changes over time, the first period being called Personnel Administration (around 1900–1960) characterized by the absence of any connection to the business and strategic decisions of organizations (Armstrong, 2008; Brandão & Parente, 1998).

The next phase of evolution (around 1960–1980) called Personal Function, began “to have humanist concerns allied to the enhancement of workers’ motivation in carrying out activities” (Serrano, 2010, p. 10). Thus, it initiates the change in the paradigm of the worker as a cost in favor of the conception of the worker as an investment, in order to achieve the organizations’ goals, “in other words, the idea that people can contribute to improve the organization of work and the functioning of the organization begins to prevail” (Serrano, 2010, p. 11).

From the 80s of the twentieth century, with the advent of market globalization, new information technologies and greater freedom of transit for products have developed. HRM is now based on the contingency perspective, which defends the idea that, in order to be effective, an organization’s HRM policies must be consistent with each other and with the policies and practices of other areas of the organization’s management (Armstrong, 2008; Baird & Meshoulam, 1988). Thus, HRM is considered strategic insofar as it adjusts to the organization’s circumstances and contributes to the definition and implementation of its strategy. In this way, the objectives of the HRM are to ensure the alignment between people’s behavior and the organizational strategy, in addition to programming policies and practices that promote it (Armstrong, 2008; Baird & Meshoulam, 1988). The contingency theory argues that “… in complex, threatening and competitive environments, companies’ internal structures become organic, communicative, participatory and based on informal relationships” (Serrano, 2010, p. 5).

Given the evolution of HRM and the theories that have developed along this historical path, it is important to identify how the effects of the pandemic have altered HRM practices in companies, in the context of Portugal and Brazil.

2.2 The Covid-19 Pandemic and Crisis Management in Organizations

Regarding the magnitude of the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, Sobral (2020, p. 269) said that “the fact that the virus does not spare anyone led to characterizing the epidemic as democratic, as it made no social distinctions”. However, there is no consensus, with those who defend that there is no significant difference between the victims of the pandemic and, on the other hand, those who defend that the difference existed, and that the pandemic particularly affected the poorest (Sobral, 2020).

The pandemic has cities as its backdrop, as the virus transmission seems to occur more strongly in urban environments. Cities have become communication hubs, being the arrival and departure point of people from different cities, becoming a context for contagious diseases to spread at a high rate of speed (Buckeridge & Philippi, 2020, p. 141). The globalized behavior that humanity has adopted, without borders and limits for circulation, may also have favored the rapid contagion and the spread of the virus. According to Sobral (2020, p. 266), “It is not the virus that causes the epidemic, but the human being. The virus is sedentary; it has no means of locomotion. In order to move, the virus has to pass from body to body. The word epidemic comes from the medieval Latin word ‘epidemic’, which, in turn, would be rooted in the Greek ‘epidemos’, with ‘epi’ being what circulates in the ‘demos’ (people)”.

There are some indicators that make it possible to measure the quality of a city’s response to extreme events such as a pandemic. They are, according to Buckeridge and Philippi (2020, p. 141): (1) care with contacts (social isolation); (2) the use of scientific knowledge to guide actions; (3) the design of public policies to control the spread of the disease; and (4) the provision of services that enable the care of the sick and prevent deaths. In fact, “the better the local performance in cities, the lower the number of deaths and the lower the subsequent socio-economic impacts” (Buckeridge & Philippi, 2020, p. 141).

What is surprising is to think that even with all the evolution and technological apparatus in which the world finds itself, a means of control was not identified that would immediately limit or reduce the spread, the level of contamination and the lethality of the virus, ending up causing widespread panic (Morgado et al., 2020). Despite all this technological and research evolution, what can reduce and prevent the contamination by the virus is physical distance and social isolation. According to Morgado et al., (2020, p. 4), “we were quickly led to a new paradigm that is neither immunological nor neuronal, whose contours still to be defined generate a growing anxiety that ends up reflecting in different areas of our life”.

Furthermore, a crisis situation as complex as the one that the Covid-19 pandemic brought to the world, affected all organizations regardless of their segment and size. Every type of crisis brings a context of uncertainty and insecurity and organizational crises impact the lives and routines of workers. In addition to the concern of companies regarding reduced productivity, the effects on workers’ mental health, as a result of prolonged exposure to anxiety and tension, cannot be neglected (Ruão, 2020).

Gama (2000, p. 536) states that “managing a crisis involves elaborating a series of questions such as, for example, what is a crisis, when did it occur, why did it occur, which publics are involved, what are the harmful effects provoked, what measures to implement and what lessons to draw for the future”. The more troubled an environment, the more important is the existence of adequate communication systems so that information is clear and accurate, and top management must pay great attention and importance to this aspect. The effectiveness of communication in times of crisis makes it easier for people to better understand the insecurities generated and their impacts, helping them to deal with what happens, in addition to bringing greater confidence in the performance of the leadership (Ruão, 2020).

In preparing a crisis plan, beyond the relevance given to communication systems, it is also important to monitor and consider the “factors that may be at the origin of the crisis, organizational elements (technical and human) likely to trigger a crisis situation, not neglecting signs that might reveal a hypothetical crisis situation, highlighting the target audiences that may affect the crisis (favorably or unfavorably) or that may be affected by it” (Gama, 2000, p. 538). The more timely risks are mapped, the faster it will become to generate a risk mitigation plan so that decision-making is well-directed, avoiding the improvisation of responses to the crisis (Velin & Flacher, 2020).

2.3 Reactions in Crisis Situations

The emergence of the new coronavirus brought significant changes to the current context of society. These changes that impacted on the notions and practices of health, presented new ways for the safety of social coexistence, and, of course, aspects that influenced the way of conceiving and carrying out work. The organizational world already demanded from the worker a greater adaptation and resilience to the innovations and transformations that work and its practices were having. However, the pandemic created unprecedented and, at the same time, indispensable conditions for the continuity of work tasks (Losekann & Mourão, 2020).

Overnight, practically everything changed. People had to stay confined at home for as long as possible, most workers started working remotely from home, and many of their daily habits changed. Psychological responses have also undergone changes since the pandemic began, and include: “the fear of contracting the virus, the fear of having affected family members, the sadness caused by the isolation and change of important plans, the uncertainty regarding the end of the confinement, the anxiety caused by the physical distance from family members, the mourning for the loss of family members and /or friends, apprehension in relation to the social and economic impacts of the crisis and fear of the increase in family violence” (Morgado, 2020, p. 10). These fears have led many people to have experienced symptoms of stress, anxiety or fear.

When considering the behavioral reactions that workers can present in times of crisis, Losekann and Mourão (2020) list some of the reactions, which can range from eating disorders, such as lack of appetite, sleep disorders, mood swings that can generate interpersonal conflicts, to psychological disorders, such as anxiety and panic attacks or stress. For example, “a major challenge in managing people in a teleworking regime is the perception, at a distance, of the mental health of workers. The establishment of good communication and interaction practices between team members is essential for managing people in this context” (Losekann & Mourão, 2020, p. 74). Given that teleworking was one of the alternatives that organizations used during the pandemic and that it will probably last in the post-pandemic, HRM must assess the positive and negative points of this initiative, taking into account aspects such as worker’s health, practices communication, integration between the teams and the maintenance of the employees’ commitment.

It is important to realize the relevance that work has for people in this crisis scenario. For some, work can be a resource that avoids imbalance, being a counterpoint to other situations that bring insecurity. For others, work can assume a support function, guaranteeing maintenance, even with adaptations, of a set of routines in the worker’s life. For another group of people, the fact of working reduces the feeling of abrupt stop that the confinement caused and can be a catalyst for the worker to come up with creative or less usual solutions for this new reality (Giust-Desprairies, 2020). HRM and organizational leaders must devote attention and greater support to workers who experience feelings of uncertainty and permanent anxiety as a reflection of this external crisis (Giust-Desprairies, 2020). Another type of behavior, according to Giust-Desprairies (2020), that should be monitored is related to workers who invest heavily in work, which in this case can represent an escape from feelings of anguish and concern. These professionals demonstrate hyperactivity, an exaggeration in the actions they perform and request from the people around them a similar behavior, which can disturb the evolution of teamwork.

The pandemic brought, in addition to public health issues, great challenges for the global economy and the world of work. Workers all over the world are going through a great test, whether due to the loss of their jobs and monetary rewards, the growing use of remote work or because they find themselves in situations where carrying out work activities leaves them exposed to possible contamination. HRM has an additional task to all process management and support to teams and strategies to obtain results, which is to identify solutions and create alternatives together with organizations and various stakeholders to overcome or reduce the serious impacts that are already taking place in the job market.

3 Methodology and Research Method

The methodological position followed is the interpretative one, aiming to analyze qualitative data that help to understand people’s perception and feelings, their points of view and perspectives on the studied reality (Bogdan & Biklen, 1994). This study used interviews with 17 participants, HRM managers who continued to develop their functions with the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic period. The interviews were carried out remotely via the Zoom platform. This is a convenience sample, although there was a concern to have companies from different sectors, sizes and areas of activity.

The interview guide consisted of questions about the organization represented by the interviewee, namely, which business segment, the number of employees, the location of the headquarters, the structure and number of persons in the HRM department. Regarding the interviewees, the questions were about their role in the HRM of that organization, their specific educational background and seniority in the company, followed by specific questions referring to the impact of the pandemic on the HRM processes.

Content analysis was the method adopted for data analysis (Bardin, 1977; Quivy & Campenhoudt, 2005). The analysis of the information collected through the interviews carried out was based on the criterion of categorization. As mentioned by Bardin (1977, p. 117), “categorization is an operation of classification of constituent elements of a set, by differentiation and, subsequently, by regrouping according to gender (analogy), with defined criteria”. The creation of categories was based on the literature review, together with the research questions and objectives of this investigation.

The step of creating the categories represents the identification of what the elements identified in the interviews have in common with each other, which connects them and can be grouped. To obtain the categories, according to Bardin (1977, p. 118), two steps are necessary: “the inventory to isolate the elements and the classification, which divides the elements and, therefore, seeks or imposes a certain organization to the messages”. From the categorization, the raw data are obtained in a simplified version. In this study, categorization considered the process in which the categories were defined and the elements were grouped as they were identified in the content analysis.

Tables 1 and 2 show, by interviewee and organization, the information regarding the sample. To facilitate identification at the time of data analysis and, at the same time, guarantee the preservation of the anonymity of respondents, the abbreviation COV was defined as the nomenclature for Brazilian companies, followed by letters in alphabetical order, ending with BR, resulting in COV-A-BR, COV-B-BR and sequentially for all 10 Brazilian companies. For Portuguese companies, the acronym VIR was designated, also followed by letters in alphabetical order and ending with PORT, such as VIR-A-PORT and so on, until completing the 7 Portuguese companies (Table 3).

To develop a system of coding categories according to Bogdan and Biklen (1994), some steps were taken: data reading to identify patterns and regularities, define words or phrases that represent these patterns and these words will be the coding categories. These categories are a way to classify the collected data to separate them from each other for later use in data analysis. A brief summary of the starting questions and the categorization developed are presented in Table 3.

4 Impacts of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Human Resources Management

In this section, the results achieved through the seventeen interviews carried out with HRM professionals from Brazil and Portugal will be presented and analyzed.

4.1 How have the Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic Altered Some HRM Practices in Companies in Portugal and Brazil?

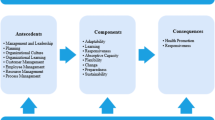

The answer to this question soon appears in the literature with Samartinho and Barradas (2020) when they refer to organizations’ relatively quick adaptability in terms of structure, systems and processes, and forms of work. By comparing the authors’ statement with the data obtained, it was possible to confirm that this adaptation to the new context was part of the reality of all organizations participating in this study. According to the interviewees, the processes of technical-administrative management, hygiene, safety and health at work, training, recruitment and selection, reception and integration, management of the work model and systems for maintaining the organizational culture, were the ones that suffered the most impacts and transformations with the pandemic.

4.1.1 Most Impactful Processes

Regarding questions in the administrative technical area, the interviewee from the company COV-G-BR states: “(…) what happened when the pandemic came was the maintenance of 100% of people at home. (…) and the impact on HR management processes was greater in personnel administration and in recruitment and selection”. According to the interviewee VIR-D-PORT:

… when everything started, we closed the factory and the stores and we were closed for as long as they forced us to stay and this had an impact on invoicing, it had a huge impact and also on the part of our human resources. Our employees felt quite insecure when they were working. [...] Recruitment and selection and training were the two processes that really changed the most during this period of the pandemic.

Another aspect mentioned mainly by Brazilian respondents was the strong digitization and simplification of the processes in HRM departments. In the words of interviewee COV-H-BR: “the personnel department has changed, to be honest it has even gotten better in some things. We had, for example, the personal signature process that had to be in person, now everything follows the digital platform and the matter is resolved”. Even when hiring young apprentices, which is part of the legal quota system of Brazilian companies, the digitization carried out by the personnel department has simplified processes, as reported by COV-I-BR “(…) I hired 15 young apprentices with a contract that was signed remotely”.

As a counterpoint, Portuguese respondents reported that the processes of the HRM department are still being digitized, which gained strength with the pandemic. Interviewee VIR-C-PORT says “(…) but this I think came before the pandemic, now everything will go through the computer system (…), in other words, the objective is to avoid everything that is paper. Of course, we often know that this is not the case (…), but I think the pandemic has shown that this effectively has to be the way forward”.

Regarding issues in the area of hygiene, health and safety at work, in the interviewee’s company VIR-E-PORT, as it is an industry, the interviewee immediately realized the need for joint action by the team in this area with the other areas of the department of HRM. In the words of the interviewee:

Since the pandemic started, one of the things that has actually increased is the activity in the human resources department, due to all the legislation, all the declarations that were necessary, all the controls and everything what we know in terms of social security procedures, but mainly discharges, medical examinations and the issue of implementing our Covid contingency plan which was promptly developed and implemented by the Hygiene, Health and Safety at Work technician.

Another important aspect is that even in the companies that have the structure of Hygiene, Health and Safety at Work independent of the HRM department, there was a joint action, having carried out many actions in relation to the health aspect, as shown in the interviews. Interviewee VIR-E-PORT mentioned:

The company already had a contingency plan, but it was a much more superficial thing compared to what we had to do now with Covid-19 and the requirement of procedures associated with our contingency plan. [...] as it is a multinational company, the protocols that were created in other countries were already required by the company and depending on the number of cases we had in the country, we had to implement more demanding procedures, according to the risk levels.

This way of functioning described in the previous citations is in line with the study by Serrano (2010), that is, the external environment has a great influence on the organization and is reflected in the strategy and performance of HRM. An example can be seen in the questions put to the interviewee’s company VIR-E-PORT by the workers, which resulted in the implementation of anticipated changes to the Portuguese government’s determinations, as transcribed below:

… when at the beginning of the pandemic, the use of masks which at the time in Portugal was not yet mandatory and the World Health Organization (WHO) still said that when used it could even be worse… we had some problems when asked if the WHO does not recommend why are you making us use this? And that’s it, there was also a struggle here against these ideas, as we were at the forefront of legislation that would impose such a requirement later on. (VIR-E-PORT)

For companies that have a large proportion of workers in operational activities, the changes that the pandemic brought in the aspects of Hygiene, Health and Safety at Work were diverse, as in the report of the interviewee COV-F-BR:

Another very strong impact was the question of the number of people that we removed. Together with the medical field, we mapped all the people who were at-risk groups over 60 years of age. Those over 60 years of age and those other people who, regardless of age, were considered by the WHO as a risk group, we excluded 100%. If the person was an administrative person, he/she continued to work from home, but no longer went to the company. Those who are not administrative, for example, a machinist, I can't give them an activity (…) we turned people away 100% for the company, but everyone continued to receive their salary and receive benefits.

From the above quotes, it is possible to see that the HRM departments, in Brazil and in Portugal, of the companies represented by the interviewees, were asked to act very quickly to support and contribute to the organizations’ strategy. This very quick response from organizations is supported by a contingent perspective, based on the idea that, to be effective, an organization’s HR policies must be consistent with each other (horizontal alignment) and with the other policies of different organizational areas (vertical alignment). Moreover, these strategies depend on the context, type, nature and circumstances of organizations (Armstrong, 2008; Baird & Meshoulam, 1988; Serrano, 2010).

Another subcategory often cited by respondents in Brazil and Portugal was related to the training process (Training). Interviewees’ reports show this subcategory as an activity that underwent changes throughout the pandemic, including in leadership development programs. For example, interviewee COV-B-BR states that:

The leadership academy was a global academy held face-to-face until the onset of the pandemic. So, all the training that took place before the pandemic took place in Sweden. [...] they do not intend to stop doing this in person, but they adapted all the training, now virtually, so the training does not stop. The quality of interaction has nothing to do with face-to-face compared to online. The transition was very fast!

For companies with operational public, the impact on mandatory training was strongly felt, as reported by the manager COV-A-BR:

We had a lot of impact on mandatory training because we really stopped, the legislation gave us this permission, postponing the validity of training, so this helped us so that we could really adapt because some groups went online. Development processes went online, with a strong impact on HRM, because we had to reinvent it overnight, but you ca not change everything to technology overnight. Thus, some trainings continued in person, however in larger rooms and with fewer people in the room.

Portuguese companies have also experienced changes in terms of worker training. In the opinion of the interviewee VIR-D-PORT, it was a moment to maintain the connection with workers who were on layoffs and who felt unmotivated with such a situation:

We took advantage of the confinement last year to do training, so people were at home in layoffs and we did a 360 training, all our human resources, regardless of category, were trained, more or less intensively, during April 2020. Everything was 100% via Zoom, everything online. There was good adherence by human resources for this training.

Added to this experience is the report of the interviewee VIR-C-PORT, from the hospital area, an area that acted so strongly throughout the pandemic period, and which reinforces how the training actions were modified and the perspectives are to be maintained online:

We are a group with several units in Portugal and now also in Madeira Island and the trainers were doing training around the units. In 2020, with the pandemic, everything stopped […]. Now the training changed, that is, it was completely reorganized and almost all training is online and costs are avoided. There are no more travel costs for trainers. And for people, they can take the training now online, at any time at work, that is, we no longer have to define that it has to be that day, at that time, in the classroom and everyone has to be present. […] There are trainings in which it is essential that they be in person, but most of the trainings, at this time, will continue in this online register.

The quotes above are representative of what the interviewees reported regarding the way and process that was adopted to carry out and maintain training processes and how this transition to online was experienced. According to Tanure (2021, p. 1), these somewhat abrupt changes in organizations occur because “the pandemic forced companies to accelerate their digital transformation movements. They occurred suddenly, intensely and, for the most part, disorganized. That is how big changes happen, pushed by external factors, and not by management deliberation” (2021, p. 1, emphasis in the original). As Ribeiro (2021) said in an interview given to Oliveira (2021) from Notícias Magazine, in the online edition of April 21, 2021: “There is no way to stop. You cannot stop the wind with your hands, you cannot stop this dematerialization of everything”.

4.1.2 Recruitment and Selection Changes , Reception of New Workers and Work Model Management

The next three categories present a sequence of HRM processes and activities that are now adjusted to the online format, which are: recruitment and selection, welcoming new workers into companies and managing the work model. With the advent of the pandemic, these activities, which until the pandemic were almost entirely face-to-face, took on different forms, from the totally remote to the hybrid model.

The category recruitment and selection changes highlights recruitment and selection as a process that has undergone transformations in this pandemic period and which has great relevance for organizations, as it seeks to identify the best and most suitable professionals in the labor market for the composition of teams. This process was mentioned by respondents as the most computerized. Of the 17 interviewees, 15 mentioned that the entire process was carried out internally by the company, but only 4 (Portuguese companies) did not perform any step remotely. The others already had some stage of this process carried out online, whether it was an interview with HR, knowledge assessment or selection tests. “We carried out the selection processes practically all online, with online interviews, very few face-to-face interviews and those that were face-to-face with the entire health protocol” was what the interviewee COV-A-BR said. The interviewee continued by saying: “In operational areas it is more complicated, because people have little access to technology, but in other functions we were able to keep it online without any problem, test application, all of this online”. In the words of the interviewee COV-D-BR, “the recruitment process that used to be face-to-face is now entirely online […] today I do not have any in-person recruitment process, all of them have taken place online”.

Moving to the Portuguese context, and in the words of the interviewee VIR-F-PORT: “Usually the recruitment process during the period of confinement was being done online, (…) we did not stop, we continued to recruit online, via Zoom”. In turn, the interviewee VIR-C-PORT argues that:

Recruitment was carried out in the face-to-face model due to the specificity of the business, which is a hospital [...] in terms of selection and interviews we always continue to do it in person, we started to make a first selection online, but then we moved on to face-to-face [...] we always did it individually. Here, we do not use this form of interview for doctors. The clinical management recruits doctors because they have a very specific profile. As for the nursing staff, administrative staff and assistants, the entire process goes through the human resources department. Hence, we say that later we make the final in-person selection, at this stage with all the sanitary precautions, but it was in person because we need to assess and see if, effectively, the candidate has the profile we need.

According to Andrade (2020, p. 110), “crises are processes that, at some point, all organizations, or physical or legal entities will go through. Being attentive, watching, managing a crisis, getting the best out of it, taking advantage of opportunities is, for organizational management, a daily exercise”. It seems that the organizations managed to withdraw from this pandemic the so-called benefit for the recruitment and selection process.

After the recruitment, selection and admission of the new worker to the company, the reception stage is reached (reception of new workers), also called onboarding. This is an important HRM process, since at this time the new employee starts to feel part of the company and knows more deeply about the work activities for which he was hired. Among the practices of Brazilian and Portuguese companies to which the interviewees belonged, there was a migration from face-to-face training to the online model. As mentioned by interviewee COV-G-BR:

Another practice, which is onboarding, where you get to know all the areas of the bank and the other five companies that make up the group, it was already being all online, it was no longer being in person. So the managers recorded videos for the person to know the entire history of the bank (...) so that was great! Then a motorcycle boy would go to the person’s house to take a computer and an onboarding kit that we have: a notebook and other materials. The provisional card related to the health, food and meal plan was already delivered.

The interviewee COV-C-BR highlights the fact that as people started the activities in a remote model, it was necessary to take care to carry out a more detailed onboarding in relation to the organizational structure, so that the new employee could have a broader view about the most important connections in future interactions.

Interviewees from Portuguese companies reported less about the experience with remotely welcoming new employees, however the respondent VIR-B-PORT mentioned: “as we were prohibited from traveling between municipalities, we made the host environment completely online […], although I have no doubt that being in person would always be better to have this first contact with the company to understand and feel the process”.

As for the work model management, eminently developed in a face-to-face model by organizations, it was transferred to the telework or hybrid format due to the pandemic. This change was one of the most significant changes of this pandemic period among interviewees’ reports from both Brazilian and Portuguese companies. The technology made possible a panoply of possibilities that organizations could experiment with the resources available in this pandemic scenario, and telecommuting was applied as a way to minimize workers’ exposure to SARS-CoV-2 contamination (Cunha, 2020; Losekann & Mourão, 2020).

This transition from the face-to-face work model to remote work, in the quick way in which it was carried out, in order to contain the impacts of the pandemic on workers’ health, brought some challenges, as mentioned by the interviewee COV-D-BR:

We put 75% of people at home and we put a very large volume of people on vacation and many other people at home with no activity. For example, the company had 35 interns and I could not make them have activities. So we gave vacations to these young employees and we made a decision later that it was no longer possible to continue with the internship contract.

The interviewee COV-E-BR reported that:

The administrative, legal, financial, HR, communication support functions were all carried out under the home office system. The operation, maintenance and laboratory employees remained at the company. We adjusted transport, restaurant, medical service to ensure distance. As mining and logistics were considered essential, there was no stoppage.

The same transition from face-to-face to remote work was identified in Portuguese companies. According to the interviewee VIR-D-PORT:

For people in administrative activities, the office part, 90% did telework […] there is work here by two teams that we have, which are the buyers and the people who issue the invoices, without these purchases and those purchases from the supplier and sales to our final consumer, 70% of this team was on layoff, during the period in which the retail trade was forced to remain closed.

However, the interviewee VIR-C-PORT describes an opposite situation regarding teleworking in a company in the hospital segment:

Here the idea was exactly the opposite. All clinical professionals, doctors, nurses and assistants had to be even more present. The situation implied a lot of extra care and even all our administrative reception staff and office support staff also had to be present. In other words, what we had to ensure was that all our human resources were safe, so the first phase was to understand what we could do to create safe conditions and safe working conditions for them, so that they faced this difficult situation with some ease. That is what I say, in most companies everyone went home, in our case we all stayed here. Few administrative services went into telework.

Also with regard to telework, according to the interviewees’ reports, it is possible to see the reactions to this experience during a time of pandemic, where some of the reports already present solutions to the questions raised. The interviewee COV-F-BR found that:

The number of meetings increased. People have a time to start activities, but they do not have a time to finish. Therefore, last month we started trying to implement what we call the “Política do Cuidado” [Care Policy]. The president sent an email to all employees, saying that every day, between 12:00 and 13:30, is the company’s lunch time, so no one can have a meeting at this time. In addition, we all try to finish all meetings by 6:30 pm. The next step will be to establish a day of the week without meetings so that people can read and respond to emails, make a more specific call. [...] It is a great impact for people to manage their work time.

Some reactions to telework are associated with technological and furniture issues in workers’ homes that affect ergonomics, as mentioned by interviewee COV-H-BR, “people have difficulties, mainly in terms of structure, because the network is not the same as the one at the office, the network at people’s homes is not the same, which has an impact on telework”. A mesma situação é reforçada pelo entrevistado COV-F-BR:

We started to realize that many people are not prepared to work at home, either because of equipment or because of ergonomics. Employees began to present several aspects to be taken into account, especially people with disabilities, who find everything adapted in the office, but do not find that adaptation at home. After that, we started to think about what is being done at the company and the solution was to provide a monetary benefit so that the necessary ergonomic equipment could be purchased.

Interviewees from Portuguese companies, as can be seen in the reports that follow share these perceptions.

... [telework conditions] was one of the concerns, and we were even asked in organizational terms to raise awareness related to this. Therefore, we had a lot of communication and awareness raising, which at the time was sent to all people who were teleworking. We also had a questionnaire that was carried out […] in corporate terms and that was sent to all employees, where it made a small assessment of people's contentment, like the conditions they had at home. We also sent the message that we were here on this side as well to help with any problems that might arise. At the time, we made available many of our equipment such as chairs and monitors for people. We have kept proper records of our equipment inventory, but we have made it possible for people to take a variety of equipment home. And they even started to give more value to what we have in the office. (Interviewee VIR-E-PORT)

This dimension of telework in the work management model provides an overview of the challenges faced by companies to make telework as effective as possible for the reality of workers. On the other hand, it also demonstrates how much the workers in this way of working also experienced challenges to adapt to the work routine in relation to time management, ergonomics, among other aspects. Policies presented or under development by companies in relation to timetables, benefits for purchasing equipment to ensure ergonomics, workers’ learning of new work tools, new forms of communication, validate some of the issues addressed in the literature (Carmo et al., 2020; Losekann & Mourão, 2020; Marques, 2020; Tanure, 2021).

4.1.3 Organizational Culture

The organizational culture category aimed to identify the impacts that occurred on the organizational culture of companies due to the pandemic. However, the interviewees still report that it is not easy to see whether these impacts on culture have occurred, and if so, to what extent and what is their nature. According to interviewee VIR-D-PORT, “in terms of culture, I would say that little or nothing has changed. It takes so long to strengthen a bond between people, the organization’s culture”.

In the opinion of the interviewee VIR-E-PORT, the culture of constant change may have favored cultural adaptation resulting from the effects of the pandemic: “here at the company, people had to adapt very quickly. The automobile industry has always been an industry with many changes, so effectively the employees who work here are very used to quickly adapting to organizational and process changes”.

The rites, rituals and commemorations of organizations are moments to reinforce the organizational culture according to Freitas (1991), Schein (1996), Nepomuceno (2013), Cunha et al. (2007), Tanure (2021) and which are highly valued. This question was raised with the interviewees to find out how the pandemic affected the holding of these events. According to the interviewees’ reports, and comparing Brazil and Portugal, Brazilian companies held more events than Portuguese companies, which may reflect a trait of the Brazilian nationality culture that may have influenced the organizational culture of companies in that country.

Based on his experience, the interviewee VIR-A-PORT says: “we were so overwhelmed that we could not figure out what day it was. […] Besides, there was not time, there was not time to know if it was Father’s Day, Mother’s Day or if it was our birthday…”.

Regarding the impact of the pandemic on rites and commemorations, the interviewee COV-E-BR says that “it affected a lot, the end-of-year party was replaced by a Christmas Kit, which, however much it was celebrated, obviously did not have the same affection from previous celebrations. The birthday celebration of the month was replaced by a gift to be celebrated with the family, which was also very well-received”.

Finally, and according to the interviewee COV-A-BR, the events, commemorations continued with adjustments resulting from the pandemic: “the company celebrated ten years, but we wanted to give people a gift. So we made a party box for all employees, sending each one home, with a cake, balloons, sweets, snacks and soft drinks so that he could take a picture with his family from the celebration and post it on the social network”.

4.1.4 What are the Main Facilitators and Hindrances in Terms of HRM Adaptation in Dealing with the Effects of the Pandemic at the Labor Level?

The answer to this question, based on the reports of the interviewees, in what concerns productivity during the pandemic period, highlights that the opportunities for training carried out remotely, the crisis committees that were created in some companies to analyze the issues of the pandemic and the resulting decisions implemented in the companies, were facilitating elements. On the other hand, issues related to the unavailability of computer data network, restricted structure of computer equipment so that workers could start teleworking quickly, were listed as obstacles both in Brazilian and Portuguese companies.

A common action found between Brazilian and Portuguese companies that mapped the critical issues of the pandemic was the creation of a crisis committee, as described by respondent GOV-G-BR: “right from the start, a crisis committee was created, with human resources, information technologies, medicine, processes, operational risk and financial risk. These areas had to participate in order to be able to map all the risks”.

Among the difficulties encountered, the mobilization of workers to work at home, with conditions to carry out activities in a remote format, for the functions that allowed it, is highlighted. The data capacity for accessing the computer network during the teleworking period also added as a hindrance. According to the interviewee COV-G-BR:

The biggest problem was taking everyone home because a lot of people worked only on the desktop. Most people did not have a laptop...] the area I have has more than 100 employees, it's the customer service and no one had a laptop... Then a lot of people had to take their own computer home. The company paid Uber; there were people who wanted to take a chair too, it was up to the person to take it, but then little by little, a notebook replaced everything. For security reasons, it was necessary to have VPN available to everyone, so it was that rush, despite IT had to provide it, everything turns to human resources.

On the other hand, the technical preparation of professionals is a facilitator of the confinement process, which developed more during the layoff period. This aspect, according to the interviewee VIR-D-PORT, reinforced the skills of workers in the company’s stores and allowed them to be ready to resume activities with more and better knowledge, skills and abilities, allowing them to respond more adequately after the reopening of stores.

The category confinement effects brought relevant mentions in the subcategory referring to impacts on workers’ mental health. Both respondents in Brazil and Portugal reported that there were issues related to mental health due to the pandemic period related to isolation and telework. This situation was especially aggravated for working mothers due to the combination of a heavy working routine, as they have a mixed shift between work and domestic tasks. In addition, there were schools that closed and children at home were an added reason for concern and impact on performance. As the interviewee VIR-C-PORT mentioned: “it was immediately an added difficulty because we had schools to close and we have many mothers who had to combine childcare and work. So we now understand that all our staff were exemplary and everyone made an extra effort to continue to maintain good service at the hospital, while having to manage all the issues at home”.

O entrevistado COV-F-BR acrescentou:

Those who are alone say “I can't stand being in my house alone anymore” or those who have children say they cannot work under these conditions and the company now has the option for those who want to be able to work in the office, they are open, but it is optional. There were people who asked to come back because they were getting sick while staying at home, so the company made it optional.

Finally, the reduction of bureaucracy and simplification of processes had a favorable impulse that respondents relate to the pandemic and which is perceived as a positive result. However, there were also aspects that made it difficult, such as the mobilization of workers for telework without having notebooks available, adequate chairs to carry out the workload with adequate ergonomics, the lack of a data network sufficient for everyone to be connected at the same time, among other reports. However, these situations were resolved over time. The results are in line with the Tannure study (2021, para. 1) that describes this somewhat abrupt arrival of these digital and even structural transformations in organizations.

Systematizing, the team meetings and trainings are highlighted by the interviewees as facilitators throughout the pandemic, among the actions developed. These moments were used by the HRM to respond to the need to pass information on to people and calm the anxieties that arose. As Ruão (2020) emphasizes, the more troubled an environment, the more clear and accurate information favors the creation and existence of a climate of trust, showing that actions are being taken in favor of the best for all. And the trainings also fulfilled the expected role of training workers both for the new form of work in progress, as well as preparing them for the resumption of activities.

Among the complicating factors, the interviewees reinforced the issue of workers’ mental health, especially those who were or those still in telework. This issue was not mitigated during the pandemic and will deserve attention from the HRM for the post-pandemic management of the work teams. Aspects of mental health, extreme tiredness, depressions that were already noticed during the pandemic, may continue to appear among teams of workers in organizations, as side effects of the period lived in the last year and a half, as signaled by Velin and Flacher (2020) and Giust-Desprairies (2020). The HRM should pay special attention to these aspects, which, as mentioned by Giust-Desprairies (2020), workers are demonstrating as a reflection of the uncertainties and anxieties during the pandemic.

4.1.5 What Lessons Can HRM Learn from the Crisis Generated by Covid-19?

To answer this research question, respondents were asked to find out what lessons HRM learned from the pandemic. These learnings are associated with the maturity of the professionals, the business segment and the experiences in the HRM in which the professionals are inserted.

For the interviewee COV-C-BR:

The HRM is always that area that is the promoter and that has to think about actions for people. And we had a big challenge to solve. I think what remained, at least for me, is that we are much more capable of making the changes that we always wanted to make. For this, it is necessary to think outside the box. And how much we had to really put the rhetoric into practice. I think the positive side of this showed that we no longer have an excuse to say that we are not going to implement changes, we no longer have an excuse, we just have to learn what the importance of HRM processes, policies and practices actually is.

For the interviewee COV-B-BR, people being at the center of the strategy is a learning experience for HRM resulting from this pandemic. In the interviewee words:

I think the great thing about HRM is that we are not the owners of the school we are the educators. The educator in the sense of expanding possibilities of working together on solutions. And I think that if the leadership model is also a very retrograde model, we are to blame, because we never gave the leader the autonomy he should have had since the beginning of a process, we always say he is responsible for the leadership, but we go there and run his house. We never thought about bringing people into the strategy. So I see that today we are much more prepared to understand what a relationship is strategically, which is a relationship to seek solutions and to be able to actually involve people.

In turn, the interviewee COV-D-BR highlights the humanization on the part of the HRM as a learning experience, mentioning that:

A strong learning started in seeing people as people within organizations, another thing that was extremely important which is a flattening of hierarchy in companies. A director could have Covid and an operational professional could too, and then everyone is treated the same. So this brought people together, this implied a very strong learning of humanity and a very great care for people, a relationship of much greater trust.

Valuing and motivating human resources is the learning highlighted by the interviewee VIR-D-PORT, when he mentions: “What I learn from this confinement is the fact that human resources have a great capacity for resilience, which exceeds some expectations. However, if human resources are not recognized, they are very easily discouraged”.

From the perspective of the interviewee VIR-E-PORT, people’s safety, health and resilience are great lessons learned from this pandemic period. In the interviewee words:

The company has always prioritized the safety and health of employees. We try to have a culture of safety and proximity to employees that has always existed and is part of the organization’s habits; however, I think it was easier to demonstrate to employees that the concern with safety is undoubtedly very important for us with this issue of Covid-19. We know that if people do not feel safe and feel unhappy with what they are doing, they do not produce.

The interviewee VIR-B-PORT highlights the aspects she considers crucial, as follows:

I think that we initially learned three major lessons: one is the issue of the flexibility of remote work and the benefits of one’s own self-responsibility. I think that the pandemic only came to prove that people feel, as long as they are trained for it and as long as there is good communication, more productive and feel more recognized and motivated with a demanding type of leadership, which is self-responsible, than with a very controlling leadership. I think that is the way to go, flexibility and a lot of self-responsibility. As a second learning, we have to talk about the issue of digitization. I think that talking about digitalization will have, at least in the reality of Portugal, I do not know how it is in other countries, to understand that this will only be possible if there is a concentration between the desire of companies and the desire of the government. […] digitization cannot be just on the companies’ side, there must also be a desire on the part of governments and the existence of policies in this regard. Another fundamental pillar is undoubtedly the question of mental health. I think it was an advantage, it was an eye-opener and it was a learning experience and it has been very positive. It is helping not to stigmatize mental health, especially when people started noticing cases of people who had never had any kind of problem, such as anxiety, and with this Covid-19 issue, they found themselves with panic attacks. […] I think that the pandemic brought us this eye-opener, I think that these are going to be the three main pillars that the pandemic brought us.

The lessons learned indicate a closer action by the HRM, which integrates what was experienced throughout the pandemic with what comes next, that is, which represents changes in the performance of companies in relation to people, as mentioned by Tanure (2021). In short, acting with a more contemporary and humanized perspective, in order to deal with workers by understanding their personal needs and values and equating this with the company’s culture and labor practices. They incorporate the ability to make the work of the HRM more flexible with the unforeseen events that can happen in the workers’ routine, combined with the development of leaders and the implementation of innovation, agility and strategic positioning of human resources.

5 Conclusion

This study’s main objective was to identify the changes in HRM as a result of Covid-19 pandemic. From the study developed, it is demonstrated that the processes that HRM performs have all gone through some type of change or transformation, to a greater or lesser degree, whether it is digitization or simplification due to the pandemic. According to the interviews, such changes brought gains for those who carry out the activities, which is very positive, considering that the focus of HRM professionals should be the support and development of professionals and the organization’s leadership, promoting the alignment of the organization’s strategy with HRM practices and policies. These changes allowed to gain time given the rapid evolution throughout the pandemic, and will therefore allow redirecting the role of HRM in companies to its essence.

Teleworking was one of the solutions most strongly implemented by companies in general in different countries. However, there are not only the positive points reported, as due to the long period of exposure to this type of work, tiredness and weariness is already felt in different types of workers. This situation has already been perceived by companies as an aspect to be taken care of for a healthy continuity of this type of work. The HRM of organizations has already presented some solutions and policies that can help this work model not be “burned out” or “failed”. After all, and according to the interviewees, both workers and companies already think of the hybrid model as a format to be implemented post-pandemic.

According to the results of this study, the mental health of workers is an issue that, in fact, should be on the agenda of HRM professionals for the next few years. It is essential to take care of people’s health and adapt the organizations’ business strategy. Finding the balance will be the big differentiator for the success of organizations. Furthermore, it is still too early to assess the consequences that this entire process will have on everyone’s lives.

Leaders were forced to make decisions and act in the heat of the pandemic and had the support of companies to implement such actions, according to interviewees’ opinions. However, as the vaccination process progresses and the return to face-to-face work approaches, there will probably be a need to rethink the actions taken and to develop leadership to work in a new environment, possibly managing teams in a hybrid model.

Comparatively, Brazil and Portugal had many similarities in the interviewees’ answers regarding the questions that were presented. In some aspects, the behavioral traits of Brazilian culture reflected in more affective actions, in order to ensure greater involvement of workers even with the challenges of distancing caused by telework, as observed in the events, rites and celebrations carried out throughout the pandemic period. These affective actions are very important for the individual commitment and maintenance of the relationship between the team members and the company and, according to the literature (Freitas, 1991; Nepomuceno, 2013; Schein, 1996; Serrano, 2010), the realization of these moments reinforces the organizational culture of the companies.

Returning to the main research question of this study, about the impacts of the pandemic on HRM, it is clear that there are many and of different orders. They range from systems and processes to mental illness. To deal with the new situations that arise from this scenario, HRM must rely on the resilience, wisdom and humanization that some interviewees referred to as lessons to be learned from the pandemic, which will allow writing the next chapters on the evolution of HRM in organizations.

References

Andrade, J. G. (2020). Crises, tecnologias e média sociais: uma reflexão sobre os novos períodos de turbulência. UMinho Editora.

Armstrong, M. (2008). Strategic human resource management—A guide to action (4th ed.). Kogan Page.

Baird, L., & Meshoulam, I. (1988). Managing two fits of strategic human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 13(1), 116–128.

Bardin, L. (1977). Análise de conteúdo. Edições 70.

Brandão, A. M., & Parente, C. (1998). Configurações da função pessoal. As especificidades do caso português. Organização e Trabalho, 20, 23–40.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (1994). Investigação qualitativa em educação: uma introdução à teoria e aos métodos. Porto editora.

Buckeridge, M. S., & Philippi, A. (2020). Ciência e políticas públicas nas cidades: Revelações da pandemia da Covid-191. Estudos Avançados, 34, 141–156.

Carmo, R. M., Tavares, I., & Cândido, A. F.(orgs.). (2020). Um Olhar Sociológico sobre a Crise Covid-19 em Livro. Observatório das Desigualdades: CIES-ISCTE.

Cunha, L. (2020). Pandemia e dinâmica social: urgências, impasses e incertezas. In M. Martins, & E. Rodrigues (Eds.), A Universidade do Minho em tempos de pandemia:Tomo I: Reflexões. UMinho Editora.

Cunha, M. P., Rego, A., Cunha, R. C., & Cardoso, C. C. (2007). Manual de Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão. Editora RH.

Freitas, M. E. D. (1991). Cultura organizacional grandes temas em debate. Revista De Administraçao De Empresas, 31, 73–82.

Gama, M. G. (2000). Quando o inferno desce à terra: A gestão de crises e a sua problemática. Revista Comunicação e Sociedade, 14(1–2), 535–542.

Giust-Desprairies, F. (2020, Junho). Reflexão sobre como o confinamento mobiliza nosso ambiente de trabalho individual e coletivo. Caderno de Administração, 28, 54–60. (Edição Especial). Universidade Estadual de Maringá.

Losekann, R. G. C. B., & Mourão, H. C. (2020). Desafios do teletrabalho na pandemia Covid-19: Quando o home vira office. Caderno De Administração, 28, 71–75.

Marques, A. P. (2020). Crise e trabalho: interrogações em tempos de pandemia. In M. Oliveira, H. Machado, J. Sarmento, & M. C. Ribeiro (Eds.), Sociedade e crise(s) (p. 31). UMinho Editora.

Morgado, J. C., Sousa, J., & Pacheco, J. A. (2020). Transformações educativas em tempos de pandemia: Do confinamento social ao isolamento curricular. Revista Práxis Educativa, 15, 1–10.

Morgado, P. (2020). Saúde mental em tempos de pandemia Covid-19: uma perspetiva da Medicina. In M. Martins, & E. Rodrigues (Eds.), A Universidade do Minho em tempos de pandemia: Tomo II: (Re)Ações. UMinho Editora.

Nepomuceno, A. (2013). Cultura organizacional: o perfil de uma empresa Brasileira - Tese de mestrado em Administração. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais.

Oliveira, S. (2021). Como impressionar numa entrevista online. Entrevistado por Oliveira, S. Revista Notícias Magazine. Edição online de 21/04/2021. https://www.noticiasmagazine.pt/2021/como-impressionar-numa-entrevista-online/estilos/comportamento/261969/. Accessed at 01/06/2021.

Quivy, R., & Campenhoudt, L.V. (2005). Manual de investigação em ciências sociais. Gradiva

Ruão, T. (2020). A emoção na comunicação de crise – aprendizagens de uma pandemia. In M. Oliveira, H. Machado, J. Sarmento, & M. C. Ribeiro (Eds.), Sociedade e crise(s) (pp. 93–101). UMinho Editora.

Samartinho, J., & Barradas, C. (2020). A Transformação Digital e Tecnologias da Informação em tempo de Pandemia. Revista da UI_IPSantarém-Unidade de Investigação do Instituto Politécnico de Santarém, 8(4), 1–6.

Schein, E. H. (1996). Culture: The missing concept in organization studies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 229–240.

Serrano, M. M. (2010). A gestão de recursos humanos: Suporte teórico, evolução da função e modelos. ISEG Universidade Técnica de Lisboa.

Sobral, J. M. (2020). Duas pandemias: Um esboço comparativo entre a “Pneumónica” 1918–19 e a Covid-19. Revista Medicina Interna (RPMI), 27(3), 264–271.

Tanure, B. (2021). Sem mudar a cultura não há transformação digital. Revista Valor Econômico. Disponível em. https://valor.globo.com/carreira/coluna/sem-mudar-a-cultura-nao-ha-transformacao-digital.ghtml. Accessed at 30/04/2021.

Velin, O., & Flacher, S. (2020). Gestion de crise: clés de lecture et perspectives Quelques clefs de lecture de la gestion des crises, à partir du COVID 19. Edição online de 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342601002_Gestion_de_crise_cles_de_lecture_et_perspectives_Quelques_clefs_de_lecture_de_la_gestion_des_crises_a_partir_du_COVID_19. Accessed at 08/12/2020.

WHO. (2020). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/whodirector-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mediabriefing-on-Covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed at 10/04/2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Santos, S., Ribeiro, J.L., Gomes, D. (2022). Impacts of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Human Resources Management: A Comparative Study of Brazil and Portugal. In: Machado, C., Davim, J.P. (eds) Organizational Management in Post Pandemic Crisis. Management and Industrial Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98052-8_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98052-8_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-98051-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-98052-8

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)